Abstract

BACKGROUND

High dietary sodium intake may induce a small, yet physiologically relevant rise in serum sodium concentration, which associates with increased systolic blood pressure. Cellular data suggest that this association is mediated by increased endothelial cell stiffness. We hypothesized that higher serum sodium levels were associated with greater arterial stiffness in participants in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT).

METHODS

Multivariable linear regression was used to examine the association between baseline serum sodium level and (i) pulse pressure (PP; n = 8,813; a surrogate measure of arterial stiffness) and (ii) carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity (CFPWV; n = 591 in an ancillary study to SPRINT).

RESULTS

Baseline mean ± SD age was 68 ± 9 years and serum sodium level was 140 ± 2 mmol/L. In the PP analysis, higher serum sodium was associated with increased baseline PP in the fully adjusted model (tertile 3 [≥141 mmol] vs. tertile 2 [139–140 mmol]; β = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.32 to 1.43). Results were similar in those with and without chronic kidney disease. In the ancillary study, higher baseline serum sodium was not associated with increased baseline CFPWV in the fully adjusted model (β = 0.35, 95% CI = –0.14 to 0.84).

CONCLUSIONS

Among adults at high risk for cardiovascular events but free from diabetes, higher serum sodium was independently associated with baseline arterial stiffness in SPRINT, as measured by PP, but not by CFPWV. These results suggest that high serum sodium may be a marker of risk for increased PP, a surrogate index of arterial stiffness.

Keywords: blood pressure, CKD, electrolyte imbalances, hypernatremia, hypertension, pulse pressure, pulse-wave velocity

Dietary sodium intake is positively associated with large elastic artery stiffness, and lowering dietary sodium intake reduces arterial stiffness.1–4 Collectively, studies in humans and animals also indicate that high dietary sodium intake increases serum sodium by 2–4 mmol/L,5–8 and a reduction is seen with lowered sodium intake.9 Notably, serum sodium levels may be slightly higher levels in hypertensive compared with normotensive adults, resulting from a decreased ability to excrete sodium.10,11

Recent evidence suggests that a small increase in serum sodium may increase systolic blood pressure (SBP) independent of extracellular volume expansion11 by promoting a rise in intracellular sodium and free calcium levels and increasing smooth muscle cell tone.12,13 Cellular evidence supports that a small, but physiologically relevant rise in serum sodium level can also increase arterial stiffness through blood pressure-independent mechanisms, by promoting stiffening of vascular endothelium, downregulation of nitric oxide production, and increased total peripheral resistance.14,15 However, the association of serum sodium with arterial stiffness has not been assessed previously in a large cohort.

The recently completed Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) provided an opportunity to evaluate the association of serum sodium with arterial stiffness in individuals at high risk for cardiovascular events. We hypothesized that higher baseline serum sodium levels would be associated with greater baseline arterial stiffness, as measured in the entire cohort by pulse pressure (PP; a surrogate index of arterial stiffness)16 and by carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity (CFPWV) in a subgroup who participated in an ancillary study. We also explored any differences in these associations in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD), who may be more susceptible to changes in serum sodium levels, given that individuals with CKD are more salt sensitive and have a reduced ability to excrete sodium.5

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

SPRINT was a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial in adults at high risk for cardiovascular events comparing standard (target SBP of <140 mm Hg) to intensive (target SBP of < 120 mm Hg) blood pressure control, with a primary composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes, as described previously.17,18 The protocol for the trial is publically available.19 Briefly, 9,361 adults ≥50 years of age with SBP of 130–180 mm Hg and increased risk of cardiovascular events (but free from diabetes mellitus and prior stroke) were recruited from 102 clinical sites between November 2010 and March 2013. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously.17 For the current analysis, all variables were assessed at baseline. Of the 9,361 participants randomized, 25 were missing serum sodium level, 18 were missing PP, and 505 were missing included covariates, leaving a total cohort of 8,813 for analysis of the association of serum sodium with PP. The most frequently missing covariate was urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR; n = 448).

A total of 649 SPRINT participants were included in an ancillary study that measured CFPWV at 11 of the 102 clinical sites, as described in detail previously.20 Of these 649 participants, 1 was missing serum sodium level and 57 were missing covariates, leaving a total cohort of 591 for the analysis of the association of serum sodium with CFPWV. The most frequently missing covariate was urinary ACR (n = 33).

All participants provided written informed consent, and this study was approved by the institutional review boards at the participating centers.

Study variables

Exposure variable.

Serum sodium was measured in fresh fasting baseline samples centrally at the University of Minnesota, using an ion-selective electrode on the Roche ModP analyzer.18 The interassay coefficient of variation for serum sodium was 1%.

Outcome variables.

PP was calculated as SBP—diastolic blood pressure as a surrogate index of arterial stiffness.16 There is a significant correlation between PP and CFPWV in the SPRINT cohort (R = 0.25, P < 0.0001), thus PP is a reasonable surrogate measure for arterial stiffness.20 Blood pressure was measured as the mean of 3 office blood pressure measurements obtained in the seated position using an automated device (Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, IL) after a 5-minute rest period, as described in detail previously.17–19

CFPWV was measured using the SphygmoCor CPV system device with software version 9.0 (AtCor Medical, Itasca, IL) following a standard protocol, as described in detail previously.20

Covariates and stratification variable.

Confounders related to serum sodium and arterial stiffness, all measured at baseline, were selected a priori as potential covariates for this analysis. Baseline questionnaires and interviews were administered by trained and certified clinical staff. Race and smoking status were determined by self-report. History of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and heart failure was determined by a detailed medical history collected at screening.17,18

Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.21 Urinary ACR was calculated as urinary albumin/urinary creatinine (mg/g), using a spot urine. Number of antihypertensive agents at baseline was calculated and diuretic use was evaluated, as described previously.17 Prevalent CKD was defined as an eGFR of 20–59 ml/minute/1.73 m2 at baseline.17–19

Statistical analyses

The association of baseline serum sodium with baseline arterial stiffness (PP and CFPWV) was analyzed using linear regression and performed as complete case analyses, with missing data assumed to be missing completely at random. Serum sodium levels were evaluated by tertile; the 2nd tertile was predefined in the analysis to serve as the reference group due to being a mid-normal value and based on previous studies demonstrating an adverse association of both higher and lower serum sodium levels with clinical outcomes.22–25 We decided a priori to use serum sodium tertiles to better explore the relationship between the exposure and outcomes variables.

In each analysis, the initial model was unadjusted. Then multivariable-adjusted models were performed to include age, sex, race, and randomized treatment arm (model 1); model 1 plus CVD, heart failure, smoking, body mass index, eGFR, and urinary ACR (model 2); and model 2 plus number of antihypertensive agents and diuretic use at baseline (model 3). We separately considered all diuretics and thiazide diuretics. Finally, mean arterial pressure (MAP) was added to the final model (model 4), which may serve as an overcorrection, or a possible mediator of the association, along with heart rate. We also tested for an interaction between serum sodium and treatment arm in the fully adjusted model (model 4). As there was no significant interaction in either of the analyses (P ≥ 0.23 for both), stratified analyses were not performed. We also evaluated the 2-way interactions of serum sodium with both sex and race.

As a sensitivity analysis, we also categorized serum sodium level based on clinical cutoffs (hyponatremia: <136 mmol/L; normonatremia: 136–145 mmol/L, and hypernatremia: >145 mmol/L). Also, we decided a priori to perform stratified analyses according to CKD and non-CKD groups regardless of the interaction term, as individuals with CKD may be more susceptible to changes in serum sodium levels, given that individuals with CKD are more salt sensitive and have a reduced ability to excrete sodium, which contributes to a small rise in serum sodium levels.5

Indices of arterial stiffness and covariates at baseline were summarized by serum sodium tertiles and presented as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. Comparisons across tertiles were made using a chi-square test for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Two-tailed values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics at baseline with PP as the outcome variable

A total of 8,813 adults who participated in the SPRINT study were included in the analysis with PP as the dependent variable. Of note, due to serum sodium being a whole number, the distribution did not divide into an equal n across tertiles. Among included participants, the mean age was 68 ± 9 years and 57% (n = 5,048) were white. The mean fasting serum sodium level was 140 ± 2 mmol/L. The mean PP was 62 ± 14 mm Hg. Individuals with the highest tertile of serum sodium levels were less likely to be white and use diuretics, and more likely to be female, have prevalent CVD, heart failure and CKD, have never smoked, have higher MAP, and have a lower eGFR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by tertile of serum sodium level

| Variable | Tertile 1 (≤138 mmol/L) (n = 1,777) | Tertile 2 (139–140 mmol/L) (n = 2,927) | Tertile 3 (≥141 mmol/L) (n = 4,109) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68 ± 9 | 67 ± 10 | 68 ± 9 | <0.0001 |

| Sex, n (%) male | 1208 (68) | 1968 (67) | 2527 (62) | <0.0001 |

| Race, n (%) white | 1131 (64) | 1686 (58) | 2231 (54) | <0.0001 |

| Study randomization group, n (%) intensive treatment group | 887 (50) | 1460 (50) | 2072 (50) | 0.88 |

| Prevalent CVD, n (%) | 346 (20) | 559 (19) | 886 (22) | 0.025 |

| Prevalent heart failure, n (%) | 55 (3) | 87 (3) | 176 (4) | 0.006 |

| Prevalent CKD, n (%) | 468 (26) | 814 (28) | 1249 (30) | 0.003 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| Never smoked | 722 (41) | 1294 (44) | 1855 (45) | |

| Former smoker | 776 (44) | 1238 (42) | 1744 (42) | |

| Current smoker | 279 (16) | 395 (14) | 510 (12) | |

| MAP, mm Hg | 98 ± 11 | 99 ± 11 | 99 ± 12 | 0.0025 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 69 ± 13 | 68 ± 12 | 68 ± 12 | 0.0002 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.2 ± 5.7 | 30.3 ± 5.9 | 29.9 ± 5.7 | <0.0001 |

| eGFR, ml/minute/1.73 m2 | 73.7 ± 21.8 | 72.5 ± 20.7 | 70.2 ± 20.1 | <0.0001 |

| Urinary albumin to creatinine ratio | 9.9 (5.8, 24.3) | 9.0 (5.4, 19.3) | 9.8 (5.7, 22.6) | 0.058 |

| Antihypertensive agents, no./patient, n (%) | 0.005 | |||

| 0 | 139 (8) | 290 (10) | 376 (9) | |

| 1 | 529 (30) | 928 (32) | 1317 (32) | |

| 2 | 656 (37) | 993 (34) | 1362 (33) | |

| 3 | 357 (20) | 595 (20) | 816 (20) | |

| 4 | 96 (5) | 121 (4) | 238 (6) | |

| Diuretic use, n (%) | 938 (53) | 1361 (47) | 1835 (45) | <0.0001 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 137 ± 2 | 140 ± 1 | 142 ± 1 | <0.0001 |

| Pulse pressure, mm Hg | 61 ± 15 | 60 ± 14 | 63 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

Data are mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or n (%).Comparisons across tertiles were made using a Chi-square test for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation); MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Relationship between serum sodium and PP at baseline

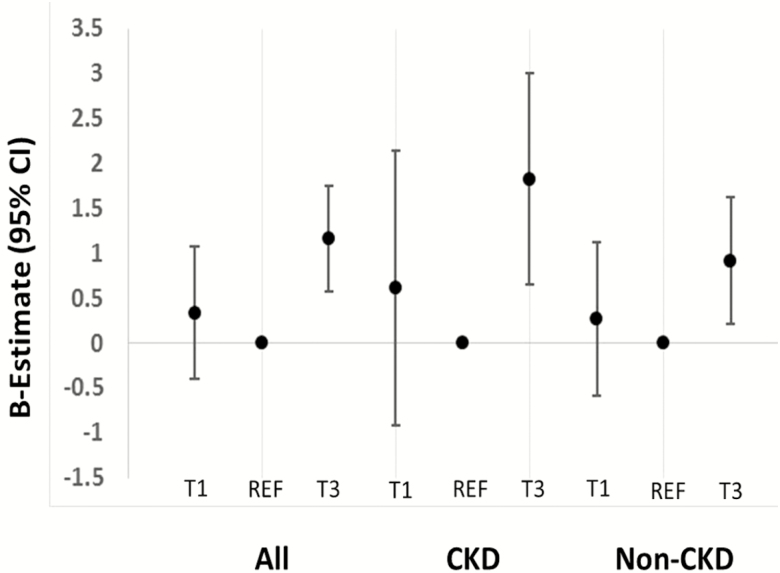

In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, higher serum sodium level (tertile 3; ≥141 mmol/L) was associated with greater arterial stiffness, as measured by PP, compared to the reference group (tertile 2; 139–140 mmol/L; model 4: tertile 3: β-estimate = 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.32 to 1.43 vs. tertile 2; Table 2; Figure 1). Results were similar when thiazide diuretic use was included in model 4 instead of any diuretic use (tertile 3: β-estimate = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.28 to 1.40 vs. tertile 2).

Table 2.

Associations (β-estimates [95% CI]) of tertiles of serum sodium level with arterial stiffness at baseline

| Pulse pressure | Tertile 1 (≤138 mmol/L) (n = 1,777) | Tertile 2 (139–140 mmol/L) (n = 2,927) | Tertile 3 (≥141 mmol/L) (n = 4,109) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 0.85 (0.01 to 1.70) | Ref | 2.25 (1.57 to 2.93) |

| Model 1 | 0.60 (–0.15 to 1.34) | Ref | 1.31 (0.71 to 1.91) |

| Model 2 | 0.27 (–0.47 to 1.01) | Ref | 1.22 (0.63 to 1.82) |

| Model 3 | 0.34 (–0.40 to 1.08) | Ref | 1.16 (0.57 to 1.76) |

| Model 4 | 0.75 (0.05 to 1.44) | Ref | 0.87 (0.32 to 1.43) |

| CFPWV | Tertile 1 (≤138 mmol/L) (n = 134) | Tertile 2 (139–140 mmol/L) (n = 184) | Tertile 3 (≥141 mmol/L) (n = 273) |

| Unadjusted | 0.35 (–0.25 to 0.96) | Ref | 0.51 (0.00 to 1.02) |

| Model 1 | 0.28 (–0.31 to 0.86) | Ref | 0.42 (–0.08 to 0.91) |

| Model 2 | 0.29 (–0.30 to 0.88) | Ref | 0.39 (–0.11 to 0.89) |

| Model 3 | 0.37 (–0.23 to 0.97) | Ref | 0.39 (–0.11 to 0.88) |

| Model 4 | 0.43 (–0.16 to 1.07) | Ref | 0.35 (–0.14 to 0.84) |

Abbreviations: ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; CI, confidence interval; CFPWV, carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation); MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, race, and randomized treatment arm.

Model 2: adjusted for covariates in model 1 plus CVD, heart failure, smoking, body mass index, eGFR, urine ACR.

Model 3: adjusted for covariates in model 2 plus number of antihypertensive medications and diuretic use at baseline.

Model 4: adjusted for covariates in model 3 plus MAP and heart rate.

Figure 1.

β-estimates (95% confidence intervals) for the association of tertiles of serum sodium (T1 = tertile 1; REF = reference group [tertile 2]; T3 = tertile 3) with pulse pressure in model 4 (adjusted for age, race, randomized treatment arm, history of cardiovascular disease, history of heart failure, smoking, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, number of antihypertensive medications, diuretic use, mean arterial pressure, and heart rate).

Participant characteristics at baseline with CFPWV as the outcome variable

A total of 591 adults who participated in the SPRINT PWV ancillary study were included in the cross-sectional analysis with CFPWV as the dependent variable. Among these participants, the mean age was 72 ± 10 years and 67% (n = 395) were white. The mean fasting serum sodium level was 140 ± 3 mmol/L and the mean CFPWV 10.8 ± 2.7 m/s. Individuals with higher serum sodium levels were less likely to be white and less diuretic use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of study participants in the pulse wave velocity ancillary study by tertile of serum sodium level

| Variable | Tertile 1 (≤138 mmol/L) (n = 134) | Tertile 2 (139–140 mmol/L) (n = 184) | Tertile 3 (≥141 mmol/L) (n = 273) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73 ± 9 | 71 ± 10 | 72 ± 10 | 0.46 |

| Sex, n (%) male | 75 (56) | 113 (61) | 169 (62) | 0.49 |

| Race, n (%) white | 103 (77) | 124 (67) | 168 (62) | 0.008 |

| Study randomization group, n (%) intensive treatment group | 69 (52) | 97 (53) | 129 (47) | 0.48 |

| Prevalent CVD, n (%) | 16 (12) | 23 (13) | 41 (15) | 0.61 |

| Prevalent CHF, n (%) | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.42 |

| Prevalent CKD, n (%) | 46 (34) | 71 (39) | 94 (34) | 0.62 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.76 | |||

| Never smoked | 55 (41) | 89 (48) | 128 (47) | |

| Former smoker | 69 (52) | 82 (45) | 125 (46) | |

| Current smoker | 10 (8) | 13 (7) | 20 (7) | |

| MAP, mm Hg | 95 ± 10 | 97 ± 12 | 98 ± 12 | 0.09 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 64 ± 11 | 66 ± 11 | 67 ± 21 | 0.28 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.0 ± 4.8 | 28.5 ± 5.3 | 28.2 ± 5.0 | 0.02 |

| eGFR, ml/minute/1.73 m2 | 69.2 ± 21.0 | 67.1 ± 19.1 | 67.1 ± 21.3 | 0.60 |

| Urinary albumin to creatinine ratio | 11.8 (6.6, 25.4) | 9.6 (6.1, 22.6) | 12.1 (6.3, 39.7) | 0.01 |

| Antihypertensive agents, no./patient, n (%) | 0.12 | |||

| 0 | 6 (5) | 19 (10) | 24 (9) | |

| 1 | 43 (32) | 70 (38) | 108 (40) | |

| 2 | 48 (36) | 65 (35) | 75 (28) | |

| 3 | 24 (18) | 20 (11) | 44 (16) | |

| 4 | 13 (10) | 10 (5) | 22 (8) | |

| Diuretic use, n (%) | 76 (57) | 81 (44) | 116 (43) | 0.020 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 136 ± 2 | 140 ± 1 | 142 ± 1 | <0.0001 |

| CFPWV, m/s | 10.8 ± 2.8 | 10.4 ± 2.6 | 11.0± 2.8 | 0.14 |

| Pulse pressure, mm Hg | 67 ±15 | 64 ± 14 | 66 ± 14 | 0.20 |

Data are mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or n (%).Comparisons across tertiles were made using a Chi-square test for categorical data and ANOVA for continuous variables. Abbreviations: CFPWV, carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation); MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Relationship between serum sodium and CFPWV at baseline

In unadjusted analysis, higher serum sodium level (tertile 3; ≥ 141 mmol/L) was associated with greater arterial stiffness, as measured by CFPWV, compared to the reference group (tertile 2; 139–140 mmol/L). However, in the fully adjusted model, there was no longer an association of serum sodium with CFPWV (Table 2). Results were nearly identical when thiazide diuretics were included in the model instead of all diuretics (model 4: tertile 3: β-estimate = 0.33. 95% CI = –0.32 to 0.97 vs. tertile 2).

Sensitivity and stratified analyses

Using clinical cutoffs, 336 participants were classified as hyponatremic (serum sodium level <136 mmol/L), 8,417 as normonatremic (serum sodium level 136–145 mmol/L), and 60 as hypernatremic (serum sodium level >145 mmol/L) at baseline for the cross-sectional, PP analyses. Consistent with the tertile analysis, there was an association with increased PP in the hypernatremic group compared to the normonatremic group in the unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 4). A sensitivity analysis according to clinical cutoffs was not performed with CFPWV as the predictor, due to a limited sample size for such analyses.

Table 4.

Associations (β-estimates [95% CI]) of clinical cutoffs of serum sodium level with arterial stiffness at baseline

| Pulse pressure | Hyponatermia (<136 mmol/L) (n = 336) | Normonatremia (136–145 mmol/L) (n = 8,417) | Hypernatremia (>145 mmol/L) (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 4.81 (3.24 to 6.38) | Ref | 5.20 (1.55 to 8.85) |

| Model 1 | 2.67 (1.28 to 4.05) | Ref | 4.52 (1.30 to 7.74) |

| Model 2 | 1.89 (0.51 to 3.27) | Ref | 4.60 (1.40 to 7.79) |

| Model 3 | 1.85 (0.47 to 3.22) | Ref | 4.46 (1.27 to 7.64) |

| Model 4 | 2.02 (0.73 to 3.31) | Ref | 3.58 (0.61 to 6.56) |

Abbreviations: ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation); MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Model 1: adjusted for age, gender, race, and randomized treatment arm.

Model 2: adjusted for covariates in model 1 plus CVD, heart failure, smoking, body mass index, eGFR, urine ACR.

Model 3: adjusted for covariates in model 2 plus number of antihypertensive medications at baseline.

Model 4: adjusted for covariates in model 3 plus MAP and heart rate.

Stratified analyses were performed, as planned a priori, by CKD status. The association of serum sodium level with PP was significant in both the CKD and the non-CKD group for tertile 3 vs. tertile 2 in all models (Supplementary Table 1; Figure 1). Lower serum sodium (tertile 1) was associated with greater CFPWV in the CKD but not the non-CKD group (Supplementary Table 1).

Results for sensitivity and stratified analyses were very similar when thiazide diuretic use was included in the models instead of any diuretic use. The interaction terms for serum sodium with both race and sex were nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated for the first time to our knowledge that higher serum sodium level is associated with increased arterial stiffness, as measured by a surrogate index of PP, in individuals at high risk for cardiovascular events free from diabetes. This association was similar in those with and without CKD. We failed to demonstrate this association in adjusted models with the gold-standard measurement of CFPWV as the index of arterial stiffness; however, the sample size was much smaller in this ancillary study. Results were similar when using clinical cutoffs of serum sodium levels in the PP analyses.

The relationship between serum sodium and arterial stiffness has not been examined in a large study previously, including the association with PP. However, reducing dietary sodium is known to reduce arterial stiffness,1,2,4,26 and a decrease in dietary sodium intake modestly reduces serum sodium levels.9 In addition, reductions in serum sodium in response to changes in dialysate sodium concentrations in chronic hemodialysis patients induce reductions in blood pressure27,28 as well as CFPWV.29 This suggests that serum sodium may directly influence arterial stiffness.

This hypothesis is consistent with cellular evidence that increases in serum sodium promote arterial stiffness. In human endothelial cell culture models, endothelial cell stiffness, as measured by atomic force microscopy, rises steeply with increasing concentrations of sodium in the culture medium.14 In addition, a high sodium media reduces deformation of endothelial cells in response to shear stress, leading to downregulation of nitric oxide production and attenuated nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation.15 Decreased endothelial-derived nitric oxide also contributes to reduced arterial elasticity.30 Similarly, in bovine aortic endothelial cells, increasing salt concentrations progressively decrease endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity.31 Sodium can also stimulate asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, promoting the production of reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase and further contributing to arterial stiffening.32

The association of serum sodium with arterial stiffness may be mediated in part by increased MAP; however, the association remained significant even after adjustment for baseline MAP. Individuals who are salt sensitive, such as older adults or individuals with kidney disease, have a reduced ability to excrete sodium, which promotes a small rise in serum sodium, expands extracellular volume, and increases blood pressure.5 Given that individuals with CKD are more salt sensitive, we expected to see a stronger association between serum sodium and arterial stiffness in this group. Contrary to our hypothesis, in the CKD group, lower serum sodium level associated with greater PWV.

Serum sodium may also influence blood pressure independent of changes in extracellular volume, through effects on the hypothalamus, local renin–angiotensin system effects, and direct effects on the heart and vasculature.5,11 In the vasculature, increased serum sodium concentration may increase intracellular sodium and free calcium levels, increasing smooth muscle tone,12,13 as well as hypertrophy.33

Notable strengths of this study include a large sample size available for the PP analyses, including well-controlled measurement of a large number of important covariates in the setting of a clinical trial. In addition, serum sodium levels were measured fasting, which is important as timing of samples in relation to a meal can influence serum sodium level.8 Our analysis is also novel as the association between serum sodium and indices of arterial stiffness does not appear to have been evaluated previously in a large cohort.

There are also important limitations of this analysis. The results are cross-sectional, associative, and residual confounding may exist. Serum sodium level may be a marker of underlying pathophysiology rather than an independent risk factor for increased arterial stiffness or reflection of dietary sodium intake. SPRINT did not include younger adults with less CVD burden, nor did it include individuals with stroke or prior diabetes, thus these results may not apply to these populations. Hypernatremia may reflect inadequate access to water or an impaired thirst mechanism.34 In addition, many of the covariates were determined from self-report, which may have resulted in errors in characterization of potential confounders such as comorbid conditions. Power was limited for the CFPWV analyses as this variable was only measured in a subgroup who participated in this ancillary study. Information regarding dietary sodium intake or urinary sodium excretion was not collected in SPRINT.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated for the first time to our knowledge that higher serum sodium level is associated with increased arterial stiffness, as measured by a surrogate index of PP, in individuals at high risk for cardiovascular events free from diabetes. This was true both in individuals with and without CKD. These results suggest that high serum sodium may be a marker of risk for increased arterial stiffness and suggest a possible mechanism linking high dietary sodium intake to increased arterial stiffness, consistent with cellular studies. Mildly elevated serum sodium is likely to be unnoticed in contemporary clinical practice. Future studies should determine whether correction of mildly elevated serum sodium, through diet or other means, might influence arterial stiffness in older adults. In addition, future research should further evaluate the association of serum sodium with CFPWV in a larger cohort.

DISCLOSURE

The author(s) declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial is funded with Federal funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), under Contract Numbers HHSN268200900040C, HHSN268200900046C, HHSN268200900047C, HHSN268200900048C, HHSN268 200900049C, and Inter-Agency Agreement Number A-HL-13-002-001. It was also supported in part with resources and use of facilities through the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) investigators acknowledge the contribution of study medications (azilsartan and azilsartan combined with chlorthalidone) from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. All components of the SPRINT study protocol were designed and implemented by the investigators. The investigative team collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All aspects of manuscript writing and revision were carried out by the coauthors. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. For a full list of contributors to SPRINT, please see the supplementary acknowledgement list: https://www.sprinttrial.org/public/dspScience.cfm. We also acknowledge the support from the following Clinical and Translational Science Awards funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences:

Case Western Reserve University: UL1TR000439, The Ohio State University: UL1RR025755, U Penn: UL1RR024134 and UL1TR000003, Boston: UL1RR025771, Stanford: UL1TR000093, Tufts: UL1RR025752, UL1TR000073 and UL1TR001064, University of Illinois: UL1TR000050, University of Pittsburgh: UL1TR000005, UT Southwestern: 9U54TR000017-06, University of Utah: UL1TR000105-05, Vanderbilt University: UL1 TR000445, George Washington University: UL1TR000075, University of CA, Davis: UL1 TR000002, University of Florida: UL1 TR000064, University of Michigan: UL1TR000433, Tulane University: P30GM103337 COBRE Award NIGMS, Wake Forest University: UL1TR001420. The PWV ancillary study was supported by NHLBI (Mark Supiano: R01HL107241). Kristen Nowak is supported by NIDDK (K01DK103678).

REFERENCES

- 1. Avolio AP, Clyde KM, Beard TC, Cooke HM, Ho KK, O’Rourke MF. Improved arterial distensibility in normotensive subjects on a low salt diet. Arteriosclerosis 1986; 6:166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seals DR, Tanaka H, Clevenger CM, Monahan KD, Reiling MJ, Hiatt WR, Davy KP, DeSouza CA. Blood pressure reductions with exercise and sodium restriction in postmenopausal women with elevated systolic pressure: role of arterial stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jablonski KL, Fedorova OV, Racine ML, Geolfos CJ, Gates PE, Chonchol M, Fleenor BS, Lakatta EG, Bagrov AY, Seals DR. Dietary sodium restriction and association with urinary marinobufagenin, blood pressure, and aortic stiffness. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8:1952–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, Markandu ND, Anand V, Dalton RN, MacGregor GA. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension 2009; 54:482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Wardener HE, He FJ, MacGregor GA. Plasma sodium and hypertension. Kidney Int 2004; 66:2454–2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawano Y, Yoshida K, Kawamura M, Yoshimi H, Ashida T, Abe H, Imanishi M, Kimura G, Kojima S, Kuramochi M. Sodium and noradrenaline in cerebrospinal fluid and blood in salt-sensitive and non-salt-sensitive essential hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1992; 19:235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dickinson KM, Clifton PM, Burrell LM, Barrett PH, Keogh JB. Postprandial effects of a high salt meal on serum sodium, arterial stiffness, markers of nitric oxide production and markers of endothelial function. Atherosclerosis 2014; 232:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suckling RJ, He FJ, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Dietary salt influences postprandial plasma sodium concentration and systolic blood pressure. Kidney Int 2012; 81:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He FJ, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Importance of the renin system for determining blood pressure fall with acute salt restriction in hypertensive and normotensive whites. Hypertension 2001; 38:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Komiya I, Yamada T, Takasu N, Asawa T, Akamine H, Yagi N, Nagasawa Y, Ohtsuka H, Miyahara Y, Sakai H, Sato A, Aizawa T. An abnormal sodium metabolism in Japanese patients with essential hypertension, judged by serum sodium distribution, renal function and the renin-aldosterone system. J Hypertens 1997; 15:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. He FJ, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, de Wardener HE, MacGregor GA. Plasma sodium: ignored and underestimated. Hypertension 2005; 45:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bevan JA. Flow regulation of vascular tone. Its sensitivity to changes in sodium and calcium. Hypertension 1993; 22:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blaustein MP. Physiological effects of endogenous ouabain: control of intracellular Ca2+ stores and cell responsiveness. Am J Physiol 1993; 264:C1367–C1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oberleithner H, Riethmüller C, Schillers H, MacGregor GA, de Wardener HE, Hausberg M. Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:16281–16286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleming I, Busse R. Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2003; 284:R1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dart AM, Kingwell BA. Pulse pressure–a review of mechanisms and clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37:975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT; SPRINT Research Group . A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambrosius WT, Sink KM, Foy CG, Berlowitz DR, Cheung AK, Cushman WC, Fine LJ, Goff DC Jr, Johnson KC, Killeen AA, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Reboussin DM, Rocco MV, Snyder JK, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr, Whelton PK. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: the systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT). Clin Trials. 2014; 11:532–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT protocol.https://www.Sprinttrial.Org/public/protocol_current.Pdf Accessed 1 November 2012

- 20. Supiano M, Lovato L, Ambrosius WT, Bates J, Beddhu S, Drawz P, Dwyer JP, Hamburg NM, Kitzman D, Lash J, Lustigova E, Miracle CM, Oparil S, Dominic RS, Weiner DE, Taylor A, Vita JA, Yunis R, Chertow G, Chonchol M. Pulse wave velocity and central aortic pressure in Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial participants. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0203305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 145:247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoorn EJ, Rivadeneira F, van Meurs JB, Ziere G, Stricker BH, Hofman A, Pols HA, Zietse R, Uitterlinden AG, Zillikens MC. Mild hyponatremia as a risk factor for fractures: the rotterdam study. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26:1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Papacosta O, Whincup P. Mild hyponatremia, hypernatremia and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older men: a population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016; 26:12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sajadieh A, Binici Z, Mouridsen MR, Nielsen OW, Hansen JF, Haugaard SB. Mild hyponatremia carries a poor prognosis in community subjects. Am J Med 2009; 122:679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nowak KL, Yaffe K, Orwoll ES, Ix JH, You Z, Barrett-Connor E, Hoffman AR, Chonchol M. Serum sodium and cognition in older community-dwelling men. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 13:366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gates PE, Tanaka H, Hiatt WR, Seals DR. Dietary sodium restriction rapidly improves large elastic artery compliance in older adults with systolic hypertension. Hypertension 2004; 44:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suckling RJ, Swift PA, He FJ, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Altering plasma sodium concentration rapidly changes blood pressure during haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28:2181–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Inrig JK, Molina C, D’Silva K, Kim C, Van Buren P, Allen JD, Toto R. Effect of low versus high dialysate sodium concentration on blood pressure and endothelial-derived vasoregulators during hemodialysis: a randomized crossover study. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65:464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu J, Sun F, Ma LJ, Shen Y, Mei X, Zhou YL. Increasing dialysis sodium removal on arterial stiffness and left ventricular hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 2016; 26:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kinlay S, Creager MA, Fukumoto M, Hikita H, Fang JC, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide regulates arterial elasticity in human arteries in vivo. Hypertension 2001; 38:1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J, White J, Guo L, Zhao X, Wang J, Smart EJ, Li XA. Salt inactivates endothelial nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells. J Nutr 2009; 139:447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bagrov AY, Lakatta EG. The dietary sodium-blood pressure plot “stiffens”. Hypertension 2004; 44:22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gu JW, Anand V, Shek EW, Moore MC, Brady AL, Kelly WC, Adair TH. Sodium induces hypertrophy of cultured myocardial myoblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 1998; 31:1083–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Agrawal V, Agarwal M, Joshi SR, Ghosh AK. Hyponatremia and hypernatremia: disorders of water balance. J Assoc Physicians India 2008; 56:956–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.