Abstract

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is mediated by two major exotoxins, toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB), which damage the colonic epithelial barrier and induce inflammatory responses. The function of the colonic vascular barrier during CDI has not been studied. Here we report increased colonic vascular permeability in CDI mice and elevated vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) which was induced by infection with a TcdA and/or TcdB-producing strain in vivo but not with a TcdA−TcdB− isogenic mutant. TcdA or TcdB also induced VEGF-A in human colonic mucosal biopsies. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling appeared to mediate toxin-induced VEGF production in colonocytes, which can further stimulate human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. Neutralization of VEGF-A and inhibition of its signaling pathway each attenuated CDI in vivo. Compared to healthy controls, CDI patients had significantly higher serum VEGF-A, which subsequently decreased after treatment. Our findings indicate critical roles for toxin-induced VEGF-A and colonic vascular permeability in CDI pathogenesis. It may also implicate the pathophysiological significance of gut vascular barrier in response to virulence factors of enteric pathogens. As an alternative to pathogen-targeted therapy, this study may enable new host-directed therapeutic approach for severe, refractory CDI.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile infection, Toxin, TcdA, TcdB, VEGF, vascular permeability, colonic vascular barrier, gut barrier, infectious diarrhea, colitis, enteric infection

Introduction

Clostridium difficile infection is a major cause of nosocomial antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis1. TcdA and TcdB, two major C. difficile toxins, induce pro-inflammatory cytokines, disrupt tight junctions, cause cellular detachment and impair the intestinal epithelial barrier2–8. In contrast, the vascular effects of toxin exposure have not been well elucidated. Vascular changes, including angiogenesis and dilatation, have been observed in severe chronic colitis in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD)9,10 and may contribute to regional inflammation, hemorrhage, fluid secretion and mucosal damage and repair. In IBD patients, angiogenesis has been shown to be an important component of inflammation11–13 and a fundamental mechanism of microvascular adaptation to prolonged colitis14. However, for acute colitis such as CDI, the vascular response and barrier function have not been characterized.

VEGF-A, also known as vascular permeability factor (VPF), belongs to a family of growth factors involved in vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and vasodilation15. VEGF-A is upregulated by HIF singling which is involved in the response to hypoxia and promotes neovascularity16. VEGF-A induces expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), an essential molecule in mediating VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis and endothelial function via production of nitric oxide (NO) in endothelial cells17. VEGF-A production is elevated in IBD patients and in experimental colitis models11,18,19, but, whether VEGF-A plays a role in CDI, which causes acute colitis, is unknown. Our goal in this study was to evaluate VEGF-A production in response to C. difficile toxins in vivo, in vitro, ex vivo in human colonic mucosa and in CDI patients, and to elucidate the role of VEGF-mediated vascular responses in CDI pathogenesis.

Results

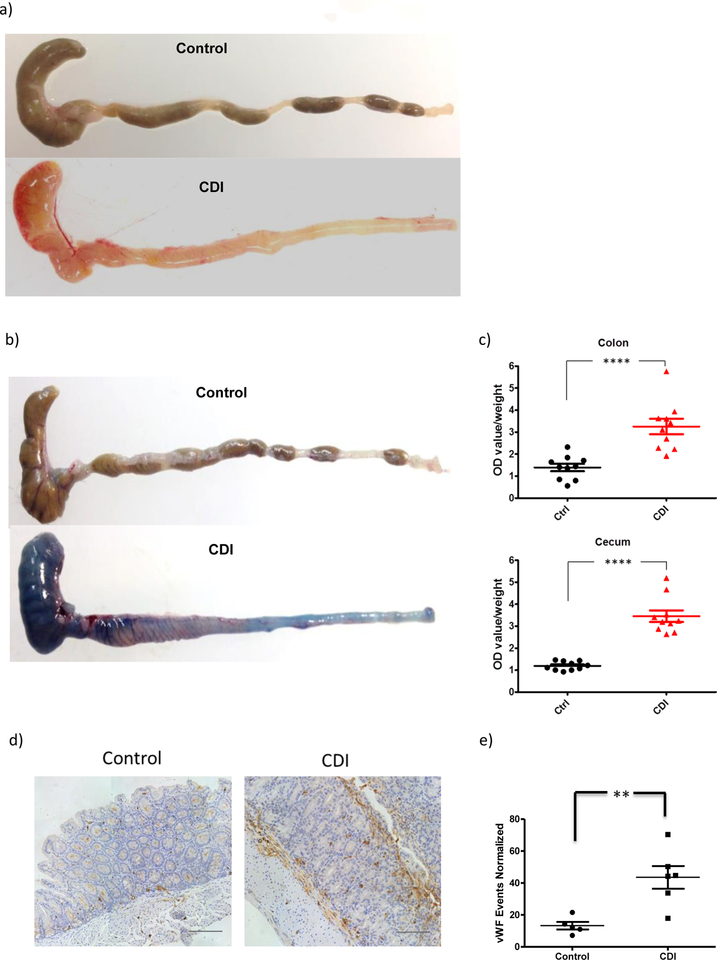

C. difficile infection increased colonic vascular permeability and angiogenesis in mice

In mice infected with C. difficile we observed increased macroscopic vasculature visibility in both the colon and cecum 36 hours (not shown) and 48 hours (Figure 1a) post-infection. To determine whether this increased vascular density is associated with altered vascular permeability in C. difficile –infected mice, we assessed vascular permeability in the colon and cecum by systemic injection of Evans blue14. Vascular permeability to the dye was remarkably increased in both the colon and cecum of CDI versus control mice (Figure 1b&c; P<0.0001 in colon; and P<0.0001 in cecum). To assess whether increased vascular permeability is also due to altered angiogenesis, we stained colon and cecum tissues with von Willebrand Factor (vWF) antibody, an established microvascular endothelial marker. Significant increase of angiogenesis was observed 48 hours post-infection (P<0.01, Figure 1d&e). These findings indicate that robust vascular responses including increased vascular permeability and angiogenesis occur early during CDI.

Figure 1. C. difficile infection led to increased colonic vascular permeability in mice.

Antibiotic-exposed C57BL6 mice were infected with 0.5×105 cfu C. difficile VPI10463. Colon and cecum tissue was harvested at 24 and 48 hours post-infection. (a) Colorectal tissue freshly obtained from control and CDI mice demonstrated more visible colonic vasculature. This experiment was repeated at least 10 times independently with similar results. (b & c) C. difficile infection led to increased colonic vascular permeability in mice. Vascular permeability was quantified by Evans Blue extravasation method. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, ****P<0.0001. N=10 biological independent animals in each group. (d & e) Significant increase of colonic vascular staining in CDI mice. Representative images of vWF staining. Scale: 100 μm N=5 (control), N=6 (CDI) biologically independent animals. **P=0.0048. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. Two-sided t-test was used for all statistical analysis above.

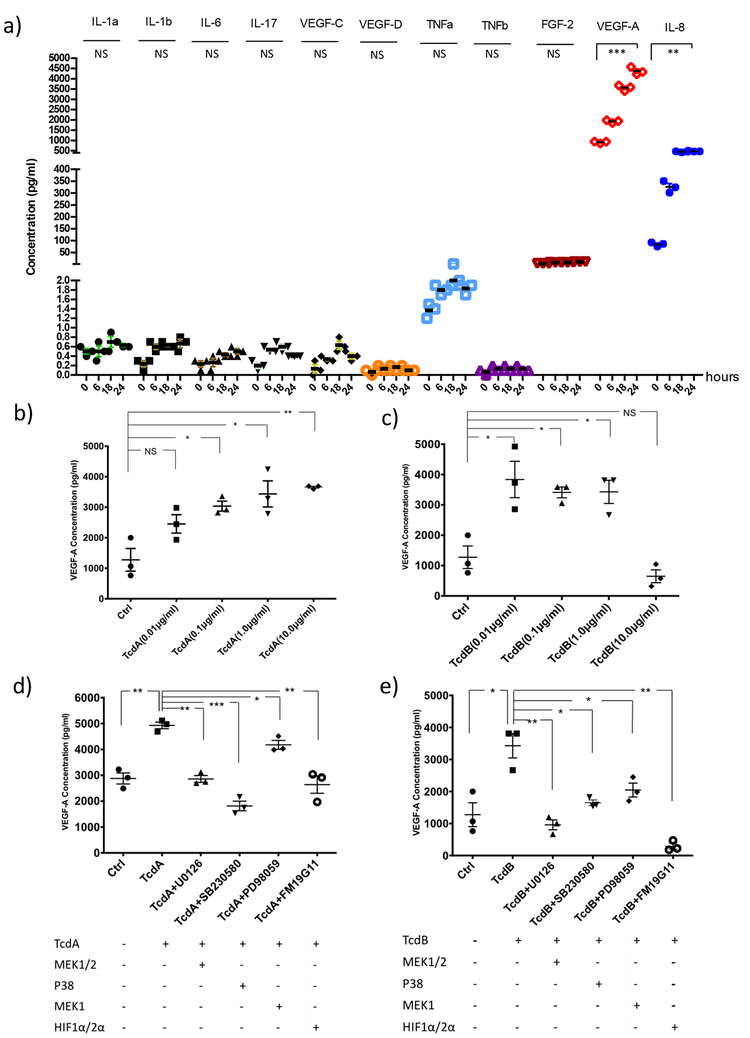

TcdA and TcdB induced VEGF-A production in human colonocytes through HIFα, p38-MAPK and MEK1/2 signaling pathways

To address the molecular mechanism of vascular changes observed in CDI, we performed a Human Angiogenesis Array & Growth Factor Array in NCM460 human colonocytes exposed to TcdA (1.0 μg/ml). As shown in Figure 2A, TcdA induced VEGF-A production in colonocytes. IL-8 was also induced, consistent with what we and others previously reported20–22. In contrast, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, TNF-α, TNF-β, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17 and FGF-2 were not significantly induced by TcdA (Figure 2a). We found that TcdA, dose-dependently, induced VEGF-A production in NCM460 colonocytes (Figure 2b). TcdB induced VEGF-A production maximally at 0.01 μg/ml (Figure 2c). At 10 μg/ml of TcdB, the highest concentration used, VEGF-A production was decreased, consistent with a loss of cell viability from the marked cytotoxicity of TcdB at this concentration. We next explored whether HIFα, p38-MAPK, and MEK/Erk signaling pathways are involved in toxin-induced VEGF-A production, using pathway specific inhibitors including FM19G11 (inhibitor of HIFα), PD98059 (inhibitor of MEK1/2 and Erk1/2), SB203580 (inhibitor of p38-MAPK), and U0126 (inhibitor of MEK1/2). We found that TcdA- and TcdB-induced VEGF-A secretion were attenuated by each of these three inhibitors in NCM460 cells, suggesting the involvement of HIFα and MAPK pathways in toxin-induced VEGF-A production (Figure 2d&e). Similar results were also observed in HT29 cells (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. C. difficile toxins induced VEGF-A production in human colonocytes; this induction was mediated by HIFα, p38-MAPK and MEK1/2 signaling pathways.

(a) Angiogenesis cytokines array demonstrated that VEGF-A and IL-8 were induced significantly in NCM460 cells treated with TcdA (1.0 μg/ml) for 6, 12 and 24 hours. IL-1α (P=0.184), IL-1β (P=0.096), IL-6 (P=0.094), IL-17 (P=0.074), VEGF-C (P=0.250), VEGF-D (P=0.427), TNFα (P=0.060), TNFβ (P=0.184), FGF-2 (P=0.250),VEGF-A (P=0.0008), IL-8 (P=0.0019). Three independent biological samples were used in each group. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for all statistical analysis.

(b & c) NCM460 cells were treated with TcdA or TcdB at various concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1.0 and 10 μg/ml) for 12 or 24 hours. VEGF-A concentration in the media was quantified by ELISA. TcdA induces dose-dependent VEGF-A production in NCM460 colonocytes, P=0.070 (ctrl vs. TcdA0.01μg/ml), P=0.012 (ctrl vs. TcdA0.1μg/ml), P=0.019 (ctrl vs. TcdA1.0μg/ml), P=0.003 (ctrl vs. TcdA10μg/ml). TcdB at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1 and 1.0 μg/ml induced VEGF-A production significantly, although not at 10 μg/ml due to cell cytotoxicity. P=0.022 (ctrl vs. TcdB0.01μg/ml), P=0.007 (ctrl vs. TcdB0.1μg/ml), P=0.016 (ctrl vs. TcdB1.0μg/ml), P=0.217 (ctrl vs. TcdB10μg/ml) (d & e) HIFα, p38-MAPK and MEK1/2 signaling pathways are all involved in TcdA or TcdB-induced VEGF-A production. TcdA- or TcdB-induced VEGF-A production in NCM460 cells was inhibited by each of these inhibitors: p38-MAPK (SB203580, 10 μM), HIFa (FM19G11, 20 μM) and MEK1/2 (U0126, 10 μM or PD98059, 20 μM). P=0.001 (ctrl vs. TcdA), P=0.005 (TcdA vs. TcdA+U0126), P=0.0002 (TcdA vs. TcdA+SB230580), P=0.024 (TcdA vs. TcdA+PD98059), P=0.003 (TcdA vs. TcdA+ FM19G11), P=0.016 (ctrl vs. TcdB), P=0.004 (TcdB vs. TcdB+U0126), P=0.011 (TcdB vs. TcdB+SB230580), P=0.034 (TcdB vs. TcdB+PD98059), P=0.001 (TcdB vs. TcdB+FM19G11). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for all statistical analysis above. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. N=3 independent biological samples. These experiments were individually repeated three times.

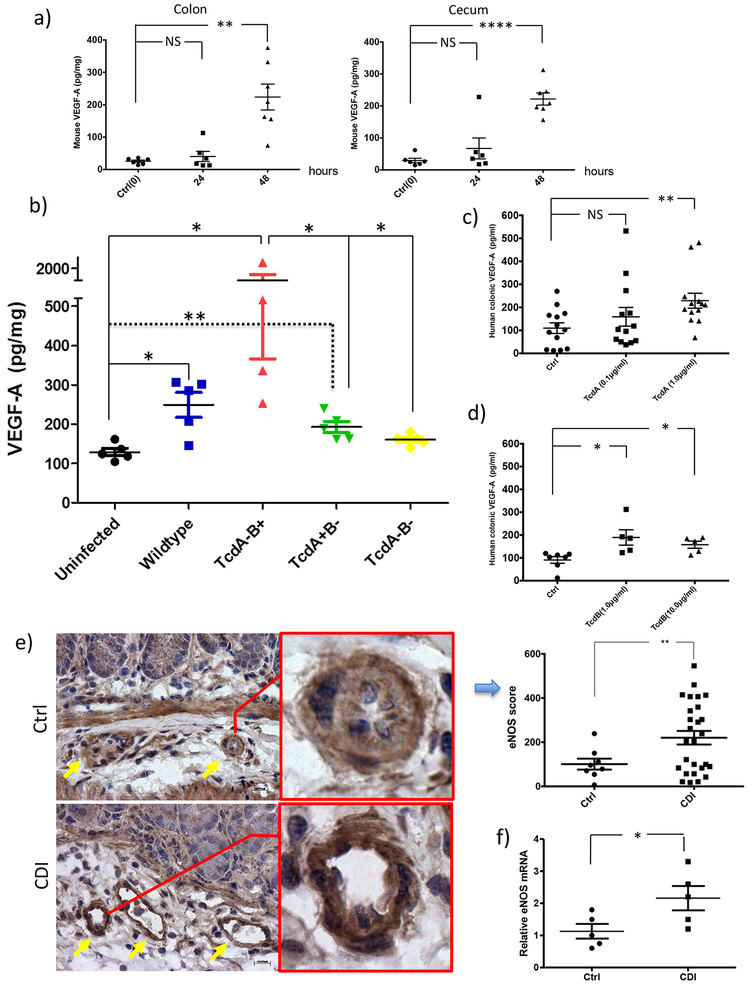

VEGF-A production was elevated in CDI mice in vivo and in human colonic mucosa exposed to toxins ex vivo

By examining this phenomenon in vivo, we found that the VEGF-A mRNA (Supplementary Figure 2) and protein levels were indeed significantly elevated in both the colon and cecum of CDI mice at 48 hours post-infection by VPI10463, a clinical strain producing high amount of both TcdA and TcdB (colon P<0.01; cecum P<0.0001; Figure 3a). To examine if there is a firm link in vivo between toxins and VEGF-A upregulation, mice were infected by wildtype and isogenic toxin mutants of C. difficile strain M7404, as previously described23. At 48 hours post infection, compared to uninfected mice, significant higher VEGF-A production was observed in the colons of mice infected by wildtype (P=0.02), TcdA−B+ (P=0.02) and TcdA+B− (P=0.079) strains but not by a double negative TcdA−B− mutant (Figure 3b), establishing the link between toxin production and VEGF-A upregulation during infection. Meanwhile, the TcdA−B+ strain induced significantly higher VEGF-A than the TcdA+B− strain (P=0.02, Figure 3b), suggesting that TcdA and TcdB have differential effects in the mouse model.

Figure 3. Toxins induced VEGF-A production in CDI mice in vivo and in human colonic mucosa ex vivo.

(a) Antibiotic-exposed mice were infected with 0.5×105 cfu C. difficile VPI10463. Tissue VEGF-A was quantified by ELISA. VEGF-A protein is significantly increased in both the colon and cecum of CDI versus control mice at 48 hours post-infection (P=0.003; P<0.0001, N=6 & 7 biologically independent animals). P=0.898 (ctrl vs. 24h, colon), P=0.001 (ctrl vs. 48h, colon), P=0.387 (ctrl vs. 24h, cecum), P<0.0001 (ctrl vs. 48h, cecum). Values are expressed as means ± SE, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis.

(b) TcdA and TcdB induced VEGF-A production during infection. Mice were infected with wildtype and isogenic toxin mutants of C. difficile strain M7404. Colonic VEGF-A at 48 hours post infection quantified by ELISA was significantly elevated in mice infected by the wildtype (TcdA+B+), TcdA-B+ and TcdA+B− mutant strains, but not in mice infected with the double negative TcdA−B− mutant strain. Data were represented as mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis, *P<0.05; **P<0.01, N=5 biological independent animals in each group except TcdA-B+ group (N=4). P=0.02 (uninfected vs. wildtype); P=0.02 (uninfected vs. TcdA-B+); P=0.0079 (uninfected vs. TcdA+B-); P=0.02 (TcdA-B+ vs. TcdA-B-); P=0.02 (TcdA-B+ vs. TcdA+B-)

(c, d) VEGF-A was induced in human colonic mucosa exposed to TcdA or TcdB. Freshly obtained human colonic mucosal biopsies were placed in ex vivo culture and exposed to TcdA (0.1, 1.0 μg/ml) or TcdB (1.0, 10 μg/ml) for 24 hours. VEGF-A released into the conditioned media was measured by Milliplex Human Cytokine Magnetic Bead assays. Data were represented as mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis, *P<0.05; **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001, NS: not significant, N=13 in TcdA & N=5 in TcdB. P=0.302 (ctrl vs. TcdA0.1μg/ml), P=0.006 (ctrl vs. TcdA1.0μg/ml), P=0.013 (ctrl vs. TcdB1.0μg/ml), P=0.012 (ctrl vs. TcdB10μg/ml).

(e) Immunohistochemical analysis of eNOS in colonic tissue of normal or CDI mice. Yellow arrows indicate sub-mucosal vascular vessels (Scale bars: 100 μm). Bar chart shows increased expression score of vascular endothelial eNOS in CDI mice compared to control (P=0.005). N=8 biological independent animals in each group.

(f) RT-PCR relative amounts of eNOS expression in control animals and those infected with CDI. Values are expressed as means ± SE, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis. *P =0.0228 compared with control, N=5 biological independent animals in each group.

We next evaluated whether VEGF-A was upregulated in toxin-exposed human colonic mucosa. We found that TcdA induced VEGF-A production in human colonic mucosa significantly at 1.0 μg/ml (P<0.01, Figure 3c). TcdB significantly induced VEGF-A at concentrations of 1.0 and 10.0 μg/ml (P=0.01 and P<0.05 respectively, Figure 3d). In comparison, IL-4 cytokine production was not significantly increased by TcdA or TcdB exposure at tested concentrations (Supplementary Figure 3).

It has been reported that the activity of eNOS increases microvascular permeability to macromolecules in response to inflammatory agents24. We therefore studied eNOS expression by immunohistochemical imaging and mRNA quantification in colorectal tissues from CDI mice. Besides increased colonic vasodilation in CDI mice (pointed by yellow arrows in Figure 3e), we also found that eNOS staining in sub-mucosal vascular endothelia of CDI mice was significantly higher than that in normal mice (P=0.005, Figure 3e). In addition, eNOS mRNA expression was significantly elevated in the colonic tissues of CDI mice (P<0.05, Figure 3f).

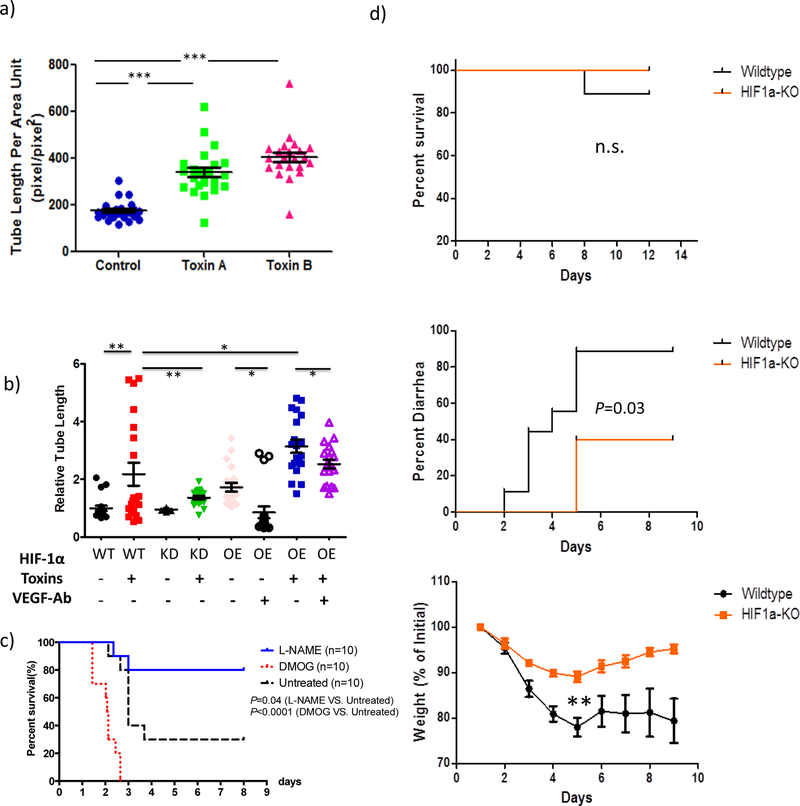

Toxin-exposed human colonocytes stimulated human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMEC) proliferation, which was mediated by the HIF-VEGF axis.

To examine the interaction between human intestinal vascular cells and colonocytes in CDI pathogenesis, we tested whether C. difficile toxin’s induction of VEGF-A expression in colonocytes promotes angiogenesis in vitro by measuring vascular tube formation of HIMECs. Compared to control naïve cells, NCM460 cells exposed to either toxin A or B significantly enhanced HIMEC tube formation (p<0.0001 each, Figure 4a). These results indicate that secreted products from colonocytes after toxin stimulation can subsequently increase angiogenesis in HIMECs.

Figure 4. Human colonocytes pre-exposed to TcdA or TcdB stimulated HIMEC proliferation, which was mediated by HIF signaling.

(a) Human colonocytes pre-exposed to TcdA or TcdB stimulated HIMEC proliferation. NCM460 cells were pre-treated with Toxin A or Toxin B at 1.0 μg/ml for 24 hours. The supernatant were ultra-filtered to remove toxins before applying to HIMEC cells. After another 24 hours, tube formation of HIMEC was quantified. Compared to naïve cell, NCM460 cells exposed to either toxin A or B significantly enhanced HIMEC tube formation (P<0.0001 each). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. Two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis.

(b) HIF-1a signaling in human colonocyes mediates toxin-induced HIMEC proliferation through VEGF. Human colonocytes HCT116 with wildtype HIF-1α (WT), HIF-1α knock down (KD), or HIF-1α over expression were stimulated by mixture of TcdA and TcdB at 1.0 μg/ml each. Using the same approach above in A, relative HIMEC tube formation were compared among all experimental groups. All cell lines responded to toxins in the subsequent HIMEC stimulation. Compared to wildtype cells (WT), HIF-1α knock down (KD) cells had significantly less stimulation of HIMEC proliferation (P=0.0065) whereas HIF-1α overexpression significantly enhanced the effect on HIMEC (P=0.04), which was attenuated by VEGF-A neutralizing antibody (P=0.03). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. Two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis.

(c) Stabilization of HIF-1α expression exacerbated CDI severity; Inhibition of eNOS protected against CDI. CDI mice were treated with DMOG (400mg/kg ip, day 1 and day 2), L-NAME (20mg/kg ip, day 1, 2 and 3) or vehicle (saline, day 1, 2 and 3) respectively. DMOG treatment significantly exacerbated the death rate in CDI mice (P<0.0001). In contrast, inhibition of eNOS by in vivo administration of L-NAME significantly protected CDI mice (P=0.04). N=10 biological independent animals in each group. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for survival analysis.

(d) Knocking out HIF-1α specifically in intestinal epithelial cells reduced CDI symptom in mice. Both HIF1α-KO mice and wildtype littermate control were challenged with C difficile using the same protocol described above. Litters from both groups are more resistant against CDI compared to our other mice experiments. There is no significant difference in the mortality rate (P=0.456, upper panel, Log-rank test). The onset of diarrhea are significantly delayed and the percentage of diarrhea was reduced in HIF1α-KO mice (middle panel, P =0.03, Log-rank test). There is significantly less weight loss in HIF1α-KO group compared to wildltype (lower panel, on day 5, P=0.008, two-sided t-test). N=9 in wildtype littermate control. N=5 in HIF1α-KO group. n.s. nonsignificant; ** P<0.01.

To better understand the molecular pathway mediating the interaction between human intestinal vascular cells and colonocytes exposed to toxins, we examined whether HIF signaling is important in this interaction by using our stably transfected HIF-1α knock down (KD) and HIF-1α over expression (OE) cells (western blot in Supplementary Figure 4). Compared to parental wildtype HCT116 cells (WT), the HIF-1α knock down (KD) cells pre-exposed to toxins had significantly less stimulation of HIMEC proliferation (P=0.0065, Figure 4b). In contrast, HIF-1α overexpression in colonocytes significantly enhanced the stimulatory effect on the proliferation of HIMEC (P=0.04, Figure 4b), which was attenuated by VEGF-A neutralizing antibody (P=0.03, Figure 4b). These data underlines the importance of HIF-VEGF axis in mediating human colonocytes in response to toxins, which subsequently stimulated colonic vascular response in this in vitro model.

HIF signaling in CDI mouse model in vivo

Since we showed above that HIF mediates TcdA- and TcdB-induced VEGF-A production in colonocytes and the subsequent stimulation of colonic vascular endothelial cells, we further tested the contribution of HIF signaling in CDI pathogenesis in vivo.

First, we tested whether stabilization of HIF expression can alter CDI outcome. DMOG is a cell permeable, competitive inhibitor of inhibitor of prolyl hydroxylase and has been used to stabilize HIF-1α expression25. As shown in Figure 4C, DMOG treatment significantly exacerbated the death rate in CDI mice (P<0.0001, N=10), whereas L-NAME, an eNOS inhibitor, significantly protected CDI mice from death (P=0.04, N=10) (Figure 4c). Weight data of both DMOG and L-NAME experiments were shown in Supplementary Figure 7.

Secondly, we wanted to test whether or not we can alter CDI disease outcome by knocking out HIF-1α signaling specifically in colonic epithelial cells, using an intestinal epithelium-specific HIF-1α knockout mice that we previously described26. As shown in Figure 4d, compared to their litter mate controls, the HIF1α-KO mice have no significant difference in the CDI mortality rate. Despite multiple attempts, both control and KO mice failed to generate similar mortality rate as our traditional CDI model. This was likely due to the fact the mice were bred and shipped from a different research facility with unknown resistant microbiota against CDI. HIF1a-KO mice have zero (0 out of 5) death whereas control group had one death (out of 9). Log-rank test, P=0.45 (Figure 4d). However, the onset of diarrhea is delayed by 3 days in HIF1α -KO mice compared to littermate controls (Log-rank test, P =0.03, Figure 4d). Moreover, HIF1α-KO mice have significantly less weight loss (thus reduced severity) in comparison to wildtype littermate controls (P=0.008, on day 5, Figure 4d).

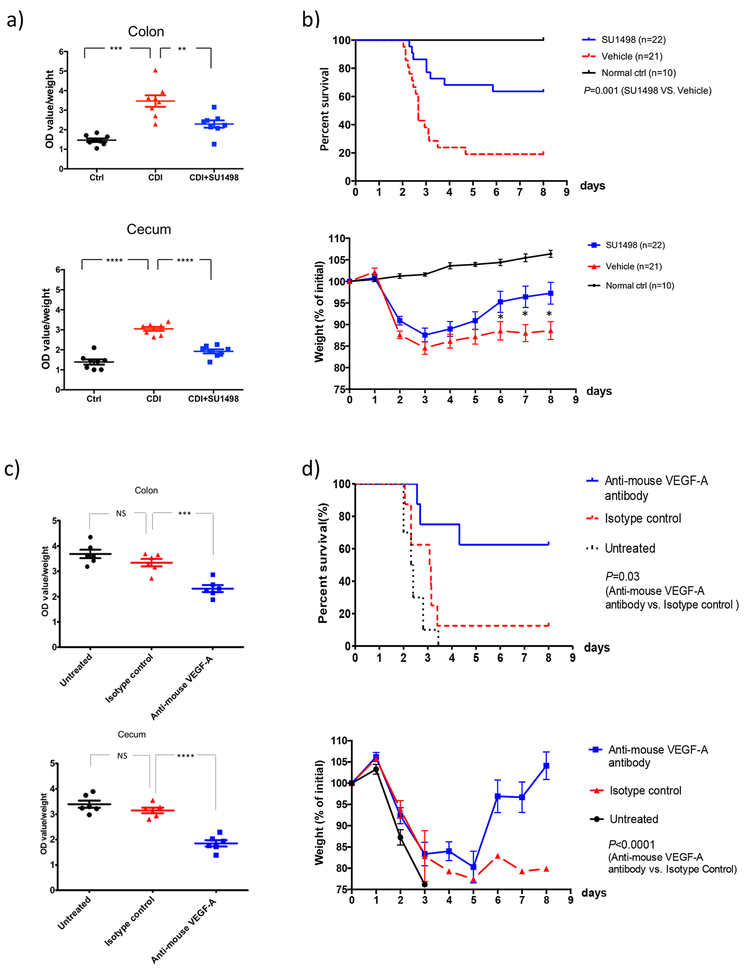

VEGFR-2 kinase inhibition reduced vascular permeability and enhanced survival in CDI mice

Since both VEGF-A production and vascular permeability are significantly elevated by C. difficile infection (as shown above), and since VEGFR-2 is the main receptor of VEGF-A27, we hypothesized that blocking VEGFR-2 kinase activity might reduce vascular permeability and disease severity in CDI. As shown in Figure 5a, administration of SU1498, a kinase inhibitor of VEGFR-2, significantly reduced vascular permeability in CDI mice (colon, P=0.006; cecum, P <0.0001, Figure 5a). SU1498 also significantly enhanced survival of CDI (63% vs. 19%, P=0.001, N=22 & 21; Figure 5b), and significantly attenuated weight loss during CDI (P=0.04, 0.01 & 0.01 on days 6, 7 and 8 respectively; Figure 5b). No significant difference was observed in the levels of spores shedded in feces or in the cytotoxic titers of cecum contents (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 5. Both VEGFR-2 kinase inhibition and Anti-VEGF-A treatment attenuated vascular permeability and protected mice from C. difficile infection.

(a) VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitor SU1498 significantly attenuated vascular permeability in mice infected with C. difficile. Colon: P=0.0002 (Ctrl vs. CDI), P=0.006 (CDI vs. CDI+SU1498); cecum: P<0.0001 (Ctrl vs. CDI), P<0.0001 (CDI vs. CDI+SU1498); N=8 biological independent animals in each group. CDI mice were treated with SU1498 (a selective inhibitor of VEGFR-2 kinase, 30 mg/kg i.p. daily for 3 days). Colonic and cecal vascular permeability was quantified as described above. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis.

(b) SU1498 treatment significantly enhanced survival of CDI versus control mice (63% vs. 19%, P=0.001, N=22&21 biological independent animals, Log-rank test) (upper panel). Relative body weights were monitored daily and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. SU1498 treatment reduced the weight loss associated with CDI as compared to vehicle control. P=0.044 (day6), 0.012 (day7), 0.012 (day8). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. N=22 & 21 biological independent animals (lower panel).

(c) Anti-VEGF-A treatment significantly attenuated vascular permeability in mice infected with C. difficile compared to isotype control (colon: P=0.0007; cecum: P <0.0001; N=6 biological independent animals in each group). CDI mice were either untreated or treated with anti-mouse VEGF-A antibody or isotype control by i.p. injection at 12h and 36h after C. difficile challenge. Colonic and cecal vascular permeability was quantified as described above. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test was used for statistical analysis. P=0.154 (untreated vs. isotype ctrl, colon), P=0.0005 (isotype ctrl vs. anti-mouse VEGF-A, colon), P=0.197 (untreated vs. isotype ctrl, cecum), P<0.0001 (isotype ctrl vs. anti-mouse VEGF-A, cecum).

(d) Anti-VEGF-A antibody treatment protected mice from weight loss (P<0.0001, data are presented as Mean ± SEM, two-sided t-test) and increased the overall survival significantly relative to isotype control (62.5% vs. 10.0%, P=0.03, Log-rank test). N=8 in anti-VEGF-A group, N=8 in isotype group, & N=10 in untreated group.

Anti-VEGF-A antibody treatment attenuated vascular permeability and protected mice from CDI

We next tested the effects of a blocking antibody to VEGF-A on permeability and clinical parameters in mice with CDI. We found that anti-VEGF-A significantly reduced vascular permeability in CDI mice compared to its isotype control (colon, P=0.0007; cecum, P <0.0001, Figure 5c). Consistent with the reduced vascular permeability, treatment with VEGF-A antibody protected mice from weight loss (P<0.0001) and increased the overall survival significantly compared to isotype control (62.5% vs. 10.0%, P=0.03) (Figure 5d). Meanwhile, we found no significant difference between isotype control and untreated control in these experiments (Figure 5c–d). Like VEGFR-2 inhibitor, anti-VEGF-A also did not influence the level of C. difficile spores shedded in the fecal samples or the cytotoxic titers of the cecum contents (Supplementary Figure 5). However, eNOS mRNA expression in the colon was significantly reduced in CDI mice treated by anti-VEGF-A (Supplementary Figure 6).

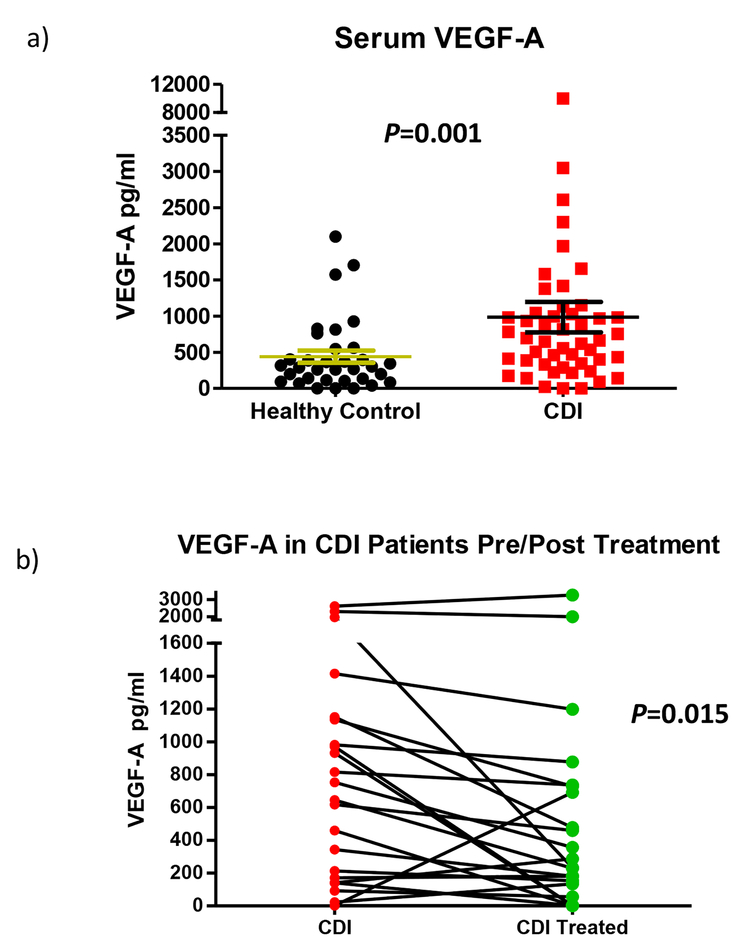

Serum levels of VEGF-A were significantly increased in patients with CDI and then decreased upon treatment

In order to further validate what we observed in experimental animal models, we decided to compare the expression of VEGF-A under physiologic conditions and acute CDI in clinical settings. We measured the levels of VEGF-A and other cytokines in the sera of healthy human controls and compared those with CDI patients using Milliplex human cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead assays (Figure 6a). The levels of VEGF-A in the sera of patients with CDI (986.0 ± 210.2 pg/ml, N=50) were markedly (P = 0.001) increased compared to healthy controls (439.9 ± 85.1 pg/ml, N=35). In contrast to VEGF-A, other cytokines such as IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, IL-33 and IFNγ were not significantly altered in these cohorts (Supplementary table 1).

Figure 6. Enhanced serum levels of VEGF-A in CDI patients and reduced VEGF-A level in follow-up sera after standard treatment.

Serum VEGF-A were measured and compared in healthy control (N=35), active CDI patients (N=50) and 23 of these CDI patients’ follow-up sera (N=23). (a) Serum levels of VEGF-A are significantly higher in CDI patients than in healthy controls (P=0.001, two-sided Mann-Whitney test). Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. (b) VEGF-A is significantly lower in follow-up sera of CDI patients than their paired sera in active CDI (P=0.015, Wilcoxon matched pairs test). Data were presented as paired (pre- and post-treatment) VEGF-A concentrations in each patient’s sera.

In addition, we also compared the levels of VEGF-A and cytokines in the plasma of CDI patients and the paired follow up sera of each patient (Figure 6b). The levels of VEGF-A in patients’ follow up sera (after treatment) were significantly reduced compared with the sera upon CDI diagnosis (interval decrease in 73.9% patients, N=23, P = 0.015), indicating that VEGF-A level is associated with CDI disease status.

Discussion

Our results indicate that C. difficile toxin-induced VEGF-A and vascular permeability contributes substantially to the pathogenesis of CDI. We observed toxin-induced VEGF-A induction in human colonocytes in vitro, in an in vivo CDI mouse model, particularly with isogenic toxin-gene mutants, and in human colonic mucosa biopsies, and more importantly, enhanced serum levels of VEGF-A in CDI patients and its correlation with disease status. There is increasing evidence that VEGF-A is an important component of chronic colitis such as IBD pathogenesis28,29. VEGF-A is elevated in distal colonic tissue in a murine colitis model18 as well as in intestinal tissues and sera of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis13,29–32. Prominent vascular changes in the colon have also been observed during clinical CDI33,34. Edema, hypoxemia and colonic wall thickening are observed by computed tomography scan and colonoscopy in CDI patients33. Besides enhanced vascular dilation and permeability observed in the CDI mouse model, we also reported marked increases in blood flow and neutrophilic invasion of the lamina propia in rabbit intestines exposed to purified C. difficile toxin A34. The substantial role of VEGF-A in both CDI and IBD may suggest a common role of VEGF-A in both acute and chronic colonic inflammation of different etiologies.

VEGF was originally described as an endothelial cell-specific mitogen. However, VEGF and VEGF receptors are additionally expressed on numerous non-endothelial cells including tumor cells. In our current study we observed that colonic epithelial cells produced and released VEGF-A in response to C. difficile toxins, indicating that colonocytes may be an important source of colonic VEGF-A, which is more typically thought to arise from vascular endothelial cells. Induction of VEGF-A production appeared to be mediated by Erk/P38-MAPK and HIFα-dependent signaling pathways (Figure 2d–e). This complements the results of our previous studies and others showing that HIF-1α/2α, p38-MAPK, and MEK/Erk signaling pathways are activated by C. difficile toxins20,21,35. In the studies reported by Hirota et al, stabilization of HIF-1α with DMOG attenuated toxin-induced injury and inflammation in mouse ileal loops injected by TcdA35. In contrast, in our CDI mouse model we found that stabilization of HIF-1α by DMOG exacerbated CDI symptoms (Figure 4c). The inconsistency may derive from the two different models (whole bacterial infection vs toxin ileal loop injection). Our knocking down and overexpression of HIF1 in HIMEC stimulation assay suggest HIF signaling in the colonocytes mediates toxin-induced VEGF production, which subsequently stimulates intestinal vascular endothelial cells (Figure 4b).

Our finding adds another layer to our understanding of barrier function in colonic infection and inflammation, an area where the epithelial cell barrier has been extensively studied but vascular permeability far less so. The target of VEGF-A is presumably colonic microvascular endothelial cells as we demonstrated in vitro that colonocytes pre-exposed to toxins subsequently stimulated human intestinal vascular cells. In addition, a more permeable vascular barrier was correlated with increased VEGF-A in the CDI mouse model. Therefore TcdA and TcdB not only directly cause a breach in the epithelial barrier by disruption of epithelial tight junctions6–8, but also indirectly induce VEGF-A production leading to a more permeable vascular intestinal barrier, which could explain the reported systemic dissemination of TcdA and TcdB in CDI animal models and in human toxemia cases36,37. In addition, the leaky vascular barrier may also contribute to C. difficile toxin-mediated transport of systemic antibodies into the gut lumen as we previously reported38. It is conceivable that there might be direct toxic effects on vasculature once toxins disseminate during the late stage of severe CDI, although it was not examined in the current study.

Notably, altering vascular permeability may not be the only role of VEGF-A in CDI pathogenesis. VEGF-A is also an important proinflammatory cytokine that facilitates endothelial cell and monocyte/macrophage migration15. VEGF itself can induce other proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-839. Meanwhile, anti-VEGF antibody significantly reduced the vascular effect induced by toxin-exposed epithelial cells (Figure 4b). However, because it did not achieve full reduction to the baseline, it may suggest that other cytokines such as IL-8 could also contribute to this effect.

As colonic vascular barrier is not well studied in enteric infections, our data provided the first example that bacterial virulence factors-induced breach of colonic vascular barrier contributes to the pathogenesis of enteric infections. Therefore VEGF-A could serve as a potential target for CDI treatment. This might enable a host-directed therapy in this enteric infection, as an alternative approach to the pathogen-targeted therapies. Avastin (Bevacizumab)is a humanized anti-VEGF-A monoclonal antibody that has been used to treat various cancers and eye diseases40. Recently, Mvasi (bevacizumab-awwb), a biosimilar of Avastin, became the first biosimilar approved by FDA for cancer treatment41. Our current report suggests that both Avastin and Mvasi may warrant consideration in treating severe, refractory CDI patients, or potentially CDI in patients with IBD, although their potential side effects in those patients should also be considered.

Materials and Methods

C. difficile culture and toxin purification

C. difficile strain VPI 10463 (ATCC 43255) stock suspension was inoculated in Difco cooked meat media (BD Diagnostic Systems) for 36 hours at 37°C. TcdA and TcdB were purified as previously described20,42,43. Wildtype and isogenic toxin mutants of C. difficile strain M7404 are listed in supplementary table 1 and have been described previously23.

Cell culture

NCM460, a non-transformed human colonocyte line, was maintained in M3D medium (INCELL Corporation, San Antonio, TX). HT-29 and HCT116 human colonic cancer cells (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM. Cells were seeded in 12-well plates, cultured in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and grown to 70%–100% confluency. Cells were serum-starved overnight and purified TcdA or TcdB was diluted in culture media then added at the indicated concentrations for varying lengths of time. In cell signaling experiments, NCM460 cells were treated with TcdA (1.0 μg/ml) or TcdB (1.0 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of specific inhibitors of p38-MAPK (SB203580, 10 μM), HIFa (FM19G11, 20 μM) and MEK1/2 (U0126, 10 μM or PD98059, 20 μM) for 12 or 24 hours. HIMECs were isolated as previously described44. Briefly, HIMECs were obtained from normal areas of the intestine from patients admitted for bowel resection. HIMECs were isolated by enzymatic digestion and subsequently cultured in MCDB131 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD), antibiotics (BioWhittaker), heparin (Sigma-Aldrich), and endothelial cell growth factor (Hybridoma Core Facility, Cleveland, OH). Cultures of HIMECs were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. HIMECs were used between passages 7 and 12. Cell lines were not further authenticated and were free of mycoplasma contamination by PlasmoTest™ Detection Kit (InvivoGen). HCT116 HIF-1α knock down (KD) and HIF-1α over expression (OE) cell lines were generated and validated as previously described45,46.

Tube Formation Assay

Human colonic epithelial cells, NCM460, were treated with Toxin A, or Toxin B at 1.0 μg/ml. In the HIF1α experiment in Figure 4B, HCT116 parental (WT) cells, HIF-1α knock down (KD) and over expression (OE) cells were treated with mixture of Toxin A and toxin B at 1.0 μg/ml each. Cell culture media were collected 24 hours later, centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min (to remove floating cells), ultra-filtered to remove toxin(s) using Amicon® Ultra Centrifugal Filters (100KD) (EMD Millipore, Inc) and applied on HIMEC (1:1 with HIMEC culture media) and tube formation was assessed 24 hours later. Cells were labeled with calcein (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 30 minutes according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were visualized under a Leica DMI6000 microscope (Leica Microsystems Wetzlar GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were captured with an Orca-R2 ER-150 CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Bridgewater, NJ) and processed with Photoshop CS5 version 12 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA), as previously described19. Relative total tube length present in each entire field (pixels/pixels2) was measured using ImageJ version 1.46d (NIH, Bethesda, MD). For these histological imaging analyses, investigators were blinded to the animals’ groups.

CDI mouse model

The mouse antibiotic-associated CDI model was employed as previously reported47. Briefly, 8-week-old female C57BL6 mice (from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used in all experimental groups. Each mouse was administrated an antibiotic mixture of kanamycin (40 mg/kg/d), gentamicin (3.5 mg/kg/d), colistin (4.2 mg/kg/d), metronidazole (21.5 mg/kg/d), and vancomycin (4.5 mg/kg/d) in drinking water for 3 days, followed, 2 days later by a single dose of clindamycin (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally 24 h prior to challenge with 0.5×105 cfu C. difficile (strains VPI10463, 3232 or CF2). The mice were monitored for daily weight and survival. In experiments of mice infected with isogenic mutant strains, the mouse model was based on a modified version of one previously described23. The intestinal epithelium-specific HIF-1α knockout mice (designated Hif1α-KO) HIF-1αΔIE and littermate controls were described as we previously reported26. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the IACUC committee of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee (Monash University AEC no. SOBSB/M/2010).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice colorectal tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 hours and then embedded and frozen in Tissue-TeK O.C.T. Compound (SAKURA Finetex, CA), and 5-μm sections were mounted on slides. Immunohistochemistry were performed using either rabbit polyclonal von Willebrand Factor (vWF) antibody (AB7356; EMD Millipore) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or rat anti-mouse eNOS antibody (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), as reported24,48. Imaging of stained colorectal tissues were captured using Zeiss microscope system. Relative density of eNOS staining in sub-mucosal vessels was analyzed and standardized using Volocity 3D Image Analysis Software 6.3 (Perkin Elmer, Inc.) Computerized vWF-stained image analysis was performed using the Scion Image Software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD) as previously described19.

Administration of VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitor (SU1498), VEGF-A antibody (2G11–2A05) or DMOG in vivo

To inhibit VEGFR-2, mice were treated with daily intraperitoneal injections of 100μl SU1498 (30 mg/kg in dimethyl sulfoxide, Sigma Aldrich, Inc.) or dimethyl sulfoxide alone starting on the day of C. difficile gavage and continuing daily for 3 days49. To neutralize VEGF-A, mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of 250 μg rat anti-mouse VEGF-A antibody (2G11–2A05) or the isotype control IgG2a (each at 12.5 mg/kg, Biolegend, Inc.)50 at 12 and 36 hours after C. difficile challenge. To stabilize HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylase, mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of 100μl DMOG (400mg/kg in saline, Cayman Chemical) starting on the day of C. difficile gavage for 2 days.

Cytokine measurement

Mice colorectal tissues were weighed and homogenized in RIPA buffer with a protein kinase inhibitor cocktail (1 g tissue in 10 ml buffer). Total protein was quantified by Bradford Assay. Tissue or human sera cytokines (VEGF-A, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, IL-33 and IFNγ) were measured by ELISA or Multiplex human cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead assays (EMD Millipore, Inc).

Vascular permeability assay

To evaluate vascular permeability as previously described51, we injected Evans Blue (30 mg/kg in 100 μl PBS; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) into the tail vein of mice 36 hours after C. difficile challenge. Mice were sacrificed 20 minutes after Evans Blue injection, photographs were taken and colorectal tissues were removed, cut along the sagittal direction with feces removed, and blotted dry. The Evans blue dye was extracted with 1 ml of formamide overnight at 55°C and measured spectrophotometrically at 600nm. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of the amounts of dye extravasation were evaluated by the unpaired t test.

Quantification of spores from mice feces

Fecal samples were collected on day 1 to 3 and 40 mg of feces were hydrated with 500 μl in sterile water for 16 h at 4°C, and then added 500 μL of absolute ethanol which were incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Samples were serially diluted and plated onto selective medium supplemented with taurocholate (0.1% w/v), Cefoxitin (16 μg/mL), L-cycloserine (250 μg/mL) (TCCFA plates). The plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 48 h, colonies counted and results expressed as the Log10 [CFU/gram of feces]

Cecum content cytotoxicity assay

3T3 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 105 cells/well. Cecum contents from mice were suspended in PBS at a ratio of 1:10, vortexed and centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 5 min). Supernatant was filter sterilized and serially diluted in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillium streptomycin and 100 μl of each dilution was added to 3T3 wells. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, plates were screened for cell rounding. The cytotoxic titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that produced rounding in at least 50% of cells per gram of cecal luminal samples under X200 magnification.

Ex vivo human colonic mucosal biopsy culture and cytokine measurement

Normal human colonic mucosa was obtained by forceps biopsy from the distal colon of healthy volunteers undergoing screening colonoscopy according to a protocol approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigation (Institutional Review Board) of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. All human biopsy samples were obtained with informed consent. Biopsies were washed with ice-cold plain medium and immediately transferred to a 24-well plate. Each biopsy well contained 0.5 ml RPMI-1640 with 100U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies) that contained TcdA (0.1 or 1.0 μg/ml) or TcdB (1.0 or 10.0 μg/ml). We maintained the cultures in 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 hours, and then harvested the supernatants for VEGF-A and cytokine measurements using Milliplex human cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead assays.

Patient sera

Stored sera from previous prospective cohort studies of the host immune response to nosocomial C. difficile infection were examined52. These included sera from healthy controls (n=35), patients with CDI upon diagnosis (n=50), and follow up CDI patients after treatment (> 5 days) (n=23). C. difficile diarrhea was defined as diarrhea not attributed to any other cause and associated with a positive stool test for C. difficile toxin. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Discarded laboratory samples and samples obtained from patients who provided written informed consent were collected. Additional information regarding clinical study design, patient demographics and risk factors for CDI has been published previously52.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis with the use of GraphPad Prism 6 software program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Analyses using the Mann–Whitney test, two-way ANOVA, t test and paired t test were performed as appropriate. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error unless otherwise indicated. Survival data were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For histological imaging and cytokine analysis, investigators were blinded to the animals’ groups or human subjects, but not blinded for survival experiments and analysis. Statistical consideration was not employed to choose the number of mice used. The sample size was chosen on the basis of our previous experience and the principles of the ‘3 Rs’ (reduction, refinement and replacement); all n values are indicated in figure legends and/or results section.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors want to thank Dr. J. Thomas Lamont from Harvard Medical School/BIDMC and Dr. Lei Lu from the University of Chicago for their critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Wen-Rong Lie from EMD Millipore for her help with the cytokine assays, and Dr. Teng Fei from Dana Farber Cancer Institute for his technical help. This work was supported by Irving W. and Charlotte F. Rabb Award (to XC), Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America Career Development Award (to XC), Young Investigator Award for Probiotic Research (to XC), NIH/NIDDL P30 DK 41301 (to CP), NIH/NIDDK U01 DK110003 (to CP), R0–1 DK60729 (to CP), Fellowship from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (to KB), .Foundation of China National Key Clinical Discipline (to JW), Foundation of China Scholarship Council (to JHuang), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grant 1107812 (to DL), Australian Research Council Future Fellowship FT120100779 (to DL) and NIH/NIAID RO1 AI116596 (to CPK) and U19 AI 109776 (to CPK).

Footnotes

Data Availability

All data reported in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bartlett JG Clostridium difficile: history of its role as an enteric pathogen and the current state of knowledge about the organism. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 18 Suppl 4, S265–272 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reineke J, et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature 446, 415–419 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres J, Jennische E, Lange S & Lonnroth I Enterotoxins from Clostridium difficile; diarrhoeogenic potency and morphological effects in the rat intestine. Gut 31, 781–785 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell TJ, et al. Effect of toxin A and B of Clostridium difficile on rabbit ileum and colon. Gut 27, 78–85 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyras D, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature 458, 1176–1179 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johal SS, Solomon K, Dodson S, Borriello SP & Mahida YR Differential effects of varying concentrations of clostridium difficile toxin A on epithelial barrier function and expression of cytokines. The Journal of infectious diseases 189, 2110–2119 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecht G, Koutsouris A, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT & Madara JL Clostridium difficile toxin B disrupts the barrier function of T84 monolayers. Gastroenterology 102, 416–423 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hecht G, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT & Madara JL Clostridium difficile toxin A perturbs cytoskeletal structure and tight junction permeability of cultured human intestinal epithelial monolayers. The Journal of clinical investigation 82, 1516–1524 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pousa ID, Mate J & Gisbert JP Angiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease. European journal of clinical investigation 38, 73–81 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaren WJ, Anikijenko P, Thomas SG, Delaney PM & King RG In vivo detection of morphological and microvascular changes of the colon in association with colitis using fiberoptic confocal imaging (FOCI). Digestive diseases and sciences 47, 2424–2433 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danese S, et al. Angiogenesis as a novel component of inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 130, 2060–2073 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deban L, Correale C, Vetrano S, Malesci A & Danese S Multiple pathogenic roles of microvasculature in inflammatory bowel disease: a Jack of all trades. The American journal of pathology 172, 1457–1466 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danese S, et al. Angiogenesis blockade as a new therapeutic approach to experimental colitis. Gut 56, 855–862 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerkic M, et al. Dextran sulfate sodium leads to chronic colitis and pathological angiogenesis in Endoglin heterozygous mice. Inflammatory bowel diseases 16, 1859–1870 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folkman J Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nature reviews. Drug discovery 6, 273–286 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin C, McGough R, Aswad B, Block JA & Terek R Hypoxia induces HIF-1alpha and VEGF expression in chondrosarcoma cells and chondrocytes. J Orthop Res 22, 1175–1181 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll J & Waltenberger J VEGF-A induces expression of eNOS and iNOS in endothelial cells via VEGF receptor-2 (KDR). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 252, 743–746 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chidlow JH Jr., et al. Differential angiogenic regulation of experimental colitis. The American journal of pathology 169, 2014–2030 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakirtzi K, et al. The neurotensin-HIF-1alpha-VEGFalpha axis orchestrates hypoxia, colonic inflammation, and intestinal angiogenesis. The American journal of pathology 184, 3405–3414 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warny M, et al. p38 MAP kinase activation by Clostridium difficile toxin A mediates monocyte necrosis, IL-8 production, and enteritis. The Journal of clinical investigation 105, 1147–1156 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii inhibits ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation both in vitro and in vivo and protects against Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced enteritis. The Journal of biological chemistry 281, 24449–24454 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, et al. Cytokines Are Markers of the Clostridium difficile-Induced Inflammatory Response and Predict Disease Severity. Clin Vaccine Immunol 24(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter GP, et al. Defining the Roles of TcdA and TcdB in Localized Gastrointestinal Disease, Systemic Organ Damage, and the Host Response during Clostridium difficile Infections. MBio 6, e00551 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duran WN, Breslin JW & Sanchez FA The NO cascade, eNOS location, and microvascular permeability. Cardiovascular research 87, 254–261 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayrapetov MK, et al. Activation of Hif1alpha by the prolylhydroxylase inhibitor dimethyoxalyglycine decreases radiosensitivity. PLoS One 6, e26064 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah YM, Matsubara T, Ito S, Yim SH & Gonzalez FJ Intestinal hypoxia-inducible transcription factors are essential for iron absorption following iron deficiency. Cell Metab 9, 152–164 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes K, Roberts OL, Thomas AM & Cross MJ Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cellular signalling 19, 2003–2012 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scaldaferri F, et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 136, 585–595 e585 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danese S Negative regulators of angiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease: thrombospondin in the spotlight. Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology 75, 22–24 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanazawa S, et al. VEGF, basic-FGF, and TGF-beta in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. The American journal of gastroenterology 96, 822–828 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsiolakidou G, Koutroubakis IE, Tzardi M & Kouroumalis EA Increased expression of VEGF and CD146 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver 40, 673–679 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapsoritakis A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in inflammatory bowel disease. International journal of colorectal disease 18, 418–422 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaMont JT & Kandel GP Toxic megacolon in ulcerative colitis. Early diagnosis and management. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 21, 102A–102D, 102H, 102K-102M passim (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurose I, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced microvascular dysfunction. Role of histamine. The Journal of clinical investigation 94, 1919–1926 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirota SA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling provides protection in Clostridium difficile-induced intestinal injury. Gastroenterology 139, 259–269 e253 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H, et al. Identification of toxemia in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS One 10, e0124235 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steele J, et al. Systemic dissemination of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B is associated with severe, fatal disease in animal models. The Journal of infectious diseases 205, 384–391 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, et al. Toxin-mediated paracellular transport of antitoxin antibodies facilitates protection against Clostridium difficile infection. Infection and Immunity (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hao Q, Wang L & Tang H Vascular endothelial growth factor induces protein kinase D-dependent production of proinflammatory cytokines in endothelial cells. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 296, C821–827 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarboe J, Gupta A & Saif W Therapeutic human monoclonal antibodies against cancer. Methods in molecular biology 1060, 61–77 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FDA Approves First Biosimilar to Treat Cancer. Cancer Discov 7, 1206 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen ML, Pothoulakis C & LaMont JT Protein kinase C signaling regulates ZO-1 translocation and increased paracellular flux of T84 colonocytes exposed to Clostridium difficile toxin A. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 4247–4254 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He D, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin A causes early damage to mitochondria in cultured cells. Gastroenterology 119, 139–150 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Binion DG, et al. Enhanced leukocyte binding by intestinal microvascular endothelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 112, 1895–1907 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakirtzi K, et al. Neurotensin Promotes the Development of Colitis and Intestinal Angiogenesis via Hif-1alpha-miR-210 Signaling. J Immunol 196, 4311–4321 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma X, Zhang H, Xue X & Shah YM Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha (HIF-2alpha) promotes colon cancer growth by potentiating Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) activity. The Journal of biological chemistry 292, 17046–17056 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, et al. A mouse model of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterology 135, 1984–1992 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huss WJ, Hanrahan CF, Barrios RJ, Simons JW & Greenberg NM Angiogenesis and prostate cancer: identification of a molecular progression switch. Cancer research 61, 2736–2743 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho SJ, George CL, Snyder JM & Acarregui MJ Retinoic acid and erythropoietin maintain alveolar development in mice treated with an angiogenesis inhibitor. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 33, 622–628 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basu A, et al. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and the development of post-transplantation cancer. Cancer research 68, 5689–5698 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thurston G, et al. Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science 286, 2511–2514 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu MY, et al. Prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 136, 1206–1214 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.