Abstract

Background:

Each year, 9 million individuals cycle in and out of jails. The under-characterization of incarceration as an exposure poses substantial challenges to understanding how varying levels of exposure to jail may affect health. Thus, we characterized levels of jail incarceration including recidivism, number of incarcerations, total and average number of days incarcerated, and time to re-incarceration.

Methods:

We created a cohort of 75,203 individuals incarcerated at the Coconino County Detention Facility in Flagstaff, Arizona, from 2001–2018 from jail intake and release records.

Results:

The median number of incarcerations during the study period was 1 (Interquartile range (IQR) 1, 2). Forty percent of individuals had >1 incarceration. The median length of stay for first observed incarcerations was 1 day (IQR 0, 5). The median total days incarcerated was 3 (IQR 1, 23). Average length of stay increased by number of incarcerations. By 18 months, 27% of our sample had been re-incarcerated.

Conclusion:

Characteristics of jail incarceration have been largely left out of public health research. A better understanding of jail incarcerations can help design analyses to assess health outcomes of individuals incarcerated in jail. Our study is an early step in shaping an understanding of jail incarceration as an exposure for future epidemiologic research.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Health disparities, Incarceration, Jail

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 40 years, the United States (US) has experienced an unparalleled epidemic of incarceration. Among persons who spent time in a correctional setting over a 1-year period, 85% were exclusively in jails and 95% of releases were from a jail facility.1 Each year, 9 million Americans cycle in and out of jails, which are short term facilities usually run by local law enforcement and/or local government agencies designed to hold individuals awaiting trial or serving a short sentence.2–5 Admission to jail is not distributed evenly among the population. For socioeconomic and historic reasons, there are substantial nationwide racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system.6 Over 60% of incarcerated populations are ethnic and racial minorities, although they make up just 30% of the US population.2,3,6 This imbalance of exposure to the criminal justice system may make incarceration an important factor in etiologic, public health research.

Although health research among individuals incarcerated in jail is imperative, discussions of the “epidemiology of incarceration” have focused almost exclusively on prison populations.7,8 When jail incarcerations are considered, they are often combined with prison incarcerations. However, they encompass different experiences. In addition, jail incarcerations are often simplified as a dichotomous variable (yes/no). Jail incarceration is rendered complex by a heterogeneity of what it means to be incarcerated. It can include a brief length of stay of a few hours or days, longer sentences of a few months to <1 year, or stays of >1 year awaiting trial. Characteristics of jail incarcerations may also include the number of distinct incarcerations. Individuals incarcerated in jail can have one incarceration or can be classified as recidivists (an individual characterized by high frequency of jail stays). Length of stay and frequency of incarceration are rarely considered when characterizing incarceration as an exposure in public health research9 and may impact health outcomes through several proposed mechanisms, some of which include increased stress,10 accelerated aging,11 infectious disease12,13, and other socioeconomic pathways.14

The under-characterization of incarceration as an exposure poses an important challenge to understanding how varying levels of exposure to the jail may affect health. Thus, our objective was to characterize levels of jail incarceration from 2001 to 2018 in Coconino County, Arizona, including recidivism, the number of times incarcerated, the total and average number of days incarcerated, and time to first observed re-incarceration. Results from this study can be used to estimate detailed associations between jail incarceration and health.

METHODS

Study population

The study protocol for the “Health Disparities in Jail Populations” is described elsewhere.15 Briefly, we used administrative jail intake and release records from iLEADS, the Coconino County Detention Facility’s record system that tracks information about an individual from booking to release. The Coconino County Detention Facility provides housing for local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies and courts in Northern Arizona. It is a regional holding facility in Flagstaff, Arizona, that houses both sentenced and un-sentenced misdemeanor and felony offenders. The Flagstaff facility has an operating capacity of 477 beds, 80% of the total 596 beds available.

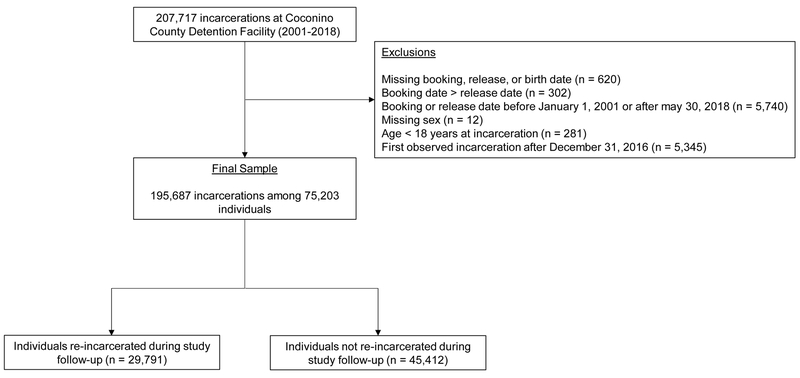

From iLEADS, we created a retrospective cohort of 207,717 individual incarcerations among individuals aged 18–91 years incarcerated in the Coconino County Detention Facility from January 1, 2001 through May 30, 2018 (Figure 1). We excluded incarcerations if (1) booking date (day an individual entered the Coconino County Detention Facility), release date (day an individual was released from the Coconino County Detention Facility), or birth date was missing (n=620); (2) the booking date was greater than the release date (n=302); (3) the booking or release date was before January 1, 2001 or after May 30, 2018 (n=5,470); (4) sex was missing (n=12); and (5) the incarceration was for an individual <18 years (n=281). We additionally excluded incarcerations for individuals with an index (first observed) incarceration after December 31, 2016 (n=5,345) to allow for an 18-month follow-up period. Our final sample consisted of 195,687 incarcerations among 75,203 individuals.

figure 1.

Study Population Flow Chart.

Footnote: Booking date: day an individual entered the Coconino County Detention Facility; Release date: day an individual was released from the Coconino County Detention Facility; Potential outcomes of individuals with no re-incarcerated during study follow-up include no re-incarceration, relocation, deportation, transfer to prison facilities permanently, and death

The data were provided from the Coconino County Detention Facility through a Data Use Agreement between Northern Arizona University and the Coconino County Detention Facility. The Northern Arizona University Institutional Review Board approved this study. Informed consent was not required, and personal identifiable information was removed.

Incarceration variables

We identified incarcerations for individuals from booking dates and release dates and counted the number of incarcerations for each entry into the Coconino County Detention Facility, and identified by different booking dates per individual. The index incarceration was defined as an individual’s first observed incarceration during the study period. We estimated the length of stay (days) for the index incarceration and subsequent incarcerations by the difference between the booking and release date. We summed the total number of days incarcerated over all incarcerations per individual and calculated the average length of stay (days) by dividing the total number of days incarcerated by the number of incarcerations per individual. We calculated time to first re-incarceration by subtracting the date of release of the first incarceration from the date of intake for the second observed incarceration, in days. Similar approaches were taken for all subsequent incarcerations.

Demographic characteristics

We obtained demographic information on age, sex, and race/ethnicity from iLEADS at an individual’s index incarceration. Age was calculated using date of birth and categorized according to methods from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and ≥55 years).16 Older adults were categorized at ≥55 based on previous work regarding accelerated aging among individuals incarcerated in jail.17 Sex was categorized as male and female. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Native American, Latinx, White, Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, and unknown. If date of birth, sex, or race/ethnicity was missing at the index incarceration and an individual had >1 incarceration, information from subsequent incarcerations was used.

Statistical analysis

We presented as numbers and percentages the descriptive characteristics of the Coconino County population incarcerated over the study period. Due to skewed distributions of number of incarcerations among our sample, we presented number of incarcerations continuously by median (interquartile range, IQR). We additionally present number of incarcerations categorically (1, 2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, 9–10, and >10) to show more specific information. We assessed the sum of the lengths of stays as the total number of days incarcerated and the average length of stay for the index incarceration and for all incarcerations. We further presented results by race/ethnic and sex categories. We estimated Kaplan-Meier survival curves18 to estimate time to first re-incarceration by age, sex, and race.

All analyses were conducted using SAS V9.4 (SAS Inc. Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Among the 75,203 individuals incarcerated in the Coconino County Detention Facility from 2001–2018, the average age was 33.8 and 81% were 18–44 years (Table 1). The majority of individuals incarcerated at Coconino County Detention Facility were male (78%), and 53% were racial/ethnic minorities.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Individuals Incarcerated in Coconino County Detention Facility (2001–2018), N = 75,203

| Demographic Characteristic | Overall (N = 75,203) |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| 18–24 | 21,172 (28) |

| 25–34 | 24,087 (32) |

| 35–44 | 15,877 (21) |

| 45–54 | 9,865 (13) |

| ≥55 | 4,202 (5.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 58,302 (78) |

| Female | 16,901 (23) |

| Race | |

| Native American | 24,631 (33) |

| Latinx | 11,753 (16) |

| Black | 3,122 (4.2) |

| White | 35,005 (47) |

| Other/Unknown | 692 (0.9) |

Abbreviations: Standard deviation (SD)

Age at index (first observed) incarceration

From 2001 to 2008, the number of admissions into the Coconino County Detention Facility increased, followed by a steady decline until 2013 and stability through 2016 (Figure 2). Results were similar for the percent of Coconino County’s population that was incarcerated in Coconino County Detention facility during the study period.

figure 2.

Number of Coconino County Detention Facility Admissions (2001-2017) Footnote: Data from 2017 and 2018 were not included due to excluding individuals with a first incarceration after December 31, 2016 in order to have sufficient follow-up of individuals after an initial incarceration

Number of incarcerations

Among the total sample, the median number of incarcerations during the study period was 1 (IQR 1, 2) with a maximum 126 incarcerations (Table 2). The median (IQR) were similar among race/ethnicity and sex groups. Of the total sample, 40% were incarcerated more than once over the study period (Table 2). Compared to other racial/ethnic and sex groups, Native American men had the highest proportion of individuals incarcerated more than once (61%) and the highest proportion of individuals incarcerated more than 10 times (9.2%). Conversely, Latinos (26%) and Black women (24%) had the lowest proportion of individuals incarcerated more than once. However, the sample size among Black women was small (n=491). White men (1.5%) and women (1.0%) had the lowest proportion of individuals incarcerated more than 10 times.

Table 2.

Number of Individuals Incarcerated in Coconino County Detention Facility, by Race and Sex (2001–2018), N = 75,203

| Total Sample (N = 75,203) |

Native American | Latinx | Black | White | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (N = 17,864) |

Women (N = 6,767) |

Men (N = 10,207) |

Women (N = 1,546) |

Men (N = 2,631) |

Women (N = 491) |

Men (N = 27,052) |

Women (N = 7,953) |

||

| Number of incarcerations, median [IQR] | 1 [1, 2] | 2 [1, 4] | 2 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 1] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] |

| Number of incarcerations, N (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | 45,412 (60) | 6,922 (39) | 3,344 (49) | 7,560 (74) | 1,109 (72) | 1,873 (71) | 374 (76) | 18,186 (67) | 5,453 (67) |

| 2 | 12,407 (17) | 3,434 (19) | 1,383 (20) | 1,152 (11) | 190 (12) | 340 (13) | 60 (12) | 4,416 (16) | 1,365 (17) |

| 3–4 | 8,450 (11) | 3,082 (17) | 1,031 (15) | 735 (7.2) | 131 (8.5) | 187 (7.1) | 28 (5.7) | 2,584 (9.4) | 682 (8.6) |

| 5–6 | 3,376 (4.5) | 1,450 (8.1) | 392 (5.8) | 305 (3.0) | 35 (2.3) | 80 (3.0) | 15 (3.1) | 882 (3.3) | 213 (2.7) |

| 7–8 | 1,688 (2.2) | 814 (4.6) | 186 (2.8) | 147 (1.4) | 30 (1.9) | 40 (1.5) | … | 355 (1.3) | 110 (1.4) |

| 9–10 | 1,086 (1.4) | 520 (2.9) | 114 (1.7) | 96 (0.9) | 19 (1.2) | 34 (1.3) | … | 249 (0.9) | 51 (0.6) |

| >10 | 2,784 (3.7) | 1,642 (9.2) | 317 (4.7) | 212 (2.1) | 32 (2.1) | 77 (2.9) | … | 416 (1.5) | 79 (1.0) |

Note. IQR = Interquartile range; 692 missing or other race/ethnicity and not included in stratified analyses; ellipses (…) denote cell size <11; Maximum number of incarcerations: total sample (126), Native American men (126), Native American women (88), Latinos (75), Latinas (29), Black men (43), Black women (33), White men (48), White women (50)

Length of stay

Among the total sample, the median length of stay (in days) for the index incarcerations was 1 (IQR 0, 5) (Table 3) with a maximum length of stay of almost 3,000 days. Although the median was similar for all racial/ethnic and sex groups, the range of length of stay varied. For example, the IQR was wider among Latinos (median=1, IQR 0, 34) and Latinas (median=1, IQR 0, 14) compared to other racial/ethnic and sex groups.

Table 3.

Length of Stays Among Individuals Incarcerated in Coconino County Detention Facility (2001–2018), N = 75,203

| Total Sample (N = 75,203) |

Native American | Latinx | Black | White | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (N = 17,864) |

Women (N = 6,767) |

Men (N = 10,207) |

Women (N = 1,546) |

Men (N = 2,631) |

Women (N = 491) |

Men (N = 27,052) |

Women (N = 7,953) |

|||

| Index incarceration | ||||||||||

| Length of stay, in days, median [IQR] | 1 [0, 5] | 1 [1, 6] | 1 [0, 3] | 1 [0, 34] | 1 [0, 14] | 1 [1, 7] | 1 [0, 5] | 1 [0, 4] | 1 [0, 2] | |

| All incarcerations | ||||||||||

| Total days incarcerated, median [IQR] | 3 [1, 23] | 9 [2, 46] | 3 [1, 16] | 10 [1, 50] | 4 [1, 33] | 3 [1, 28] | 2 [1, 16] | 1 [1, 10] | 1 [0, 6] | |

| Average length of stay, in days, by number of incarcerations, median [IQR] | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1 [0, 6.0] | 1.0 [1.0, 6.0] | 1.0 [0, 3.0] | 8.0 [1.0, 43.0] | 2.0 [1.0, 23.0] | 1.0 [1.0, 8.0] | 1.0 [1.0, 6.0] | 1.0 [0, 4.0] | 1.0, [0, 2.0] | |

| 2 | 2.5 [0.5, 7.5] | 4.0 [1.0, 9.0] | 1.5 [0.5, 5.0] | 3.5 [0.5, 15.5] | 1.0 [0.5, 4.5] | 4.0 [1.0, 24.8] | 2.0 [0.5, 13.0] | 1.5 [0.5, 6.5] | 1.0 [0.5, 5.0] | |

| 3–4 | 4.0 [1.3, 11.3] | 5.0 [2.0, 11.7] | 3.3 [1.0, 8.3] | 3.7 [1.3, 14.7] | 3.7 [1.0, 17.0] | 5.8 [1.7, 20.0] | 4.8 [0.8, 22.0] | 3.4 [0.8, 11.8] | 3.0 [0.8, 9.8] | |

| 5–6 | 6.8 [2.7, 17.8] | 7.0 [3.3, 15.6] | 5.7 [2.2, 12.8] | 6.6 [2.8, 20.5] | 6.3 [2.6, 30.2] | 10.8 [3.7, 24.8] | 8.0 [2.8, 13.8] | 6.8 [2.2, 21.2] | 4.7 [1.6, 16.4] | |

| 7–8 | 8.9 [3.9, 20.1] | 9.1 [4.5, 19.6] | 6.5 [3.1, 15.1] | 8.6 [2.8, 23.6] | 10.3 [2.7, 25.3] | 18.5 [6.7, 32.6] | … | 9.3 [3.6, 21.4] | 7.6 [2.7, 19.8] | |

| 9–10 | 11.2 [5.4, 21.6] | 10.2 [5.7, 18.3] | 8.5 [4.7, 18.7] | 15.2 [7.4, 24.1] | 15.6 [6.3, 27.4] | 17.8 [8.4, 40.4] | … | 14.0 [5.0, 23.6] | 14.2 [2.9, 23.6] | |

| >10 | 14.4 [8.6, 22.3] | 14.0 [8.6, 21.3] | 12.6 [8.2, 20.0] | 19.5 [10.4, 31.0] | 15.2 [7.6, 23.0] | 19.6 [12.5, 30.9] | … | 15.6 [8.4, 24.9] | 13.5 [6.4, 20.3] | |

Note. IQR = Interquartile range; 0 indicates they were booked and released on the same day; 692 missing or other race/ethnicity and not included in stratified analyses; ellipses (…) denote cell size <11; Maximum length of stay for index incarceration (days): total sample (2,923), Native American men (1,462), Native American women (1,121), Latinos (686), Latinas (553), Black men (877), Black women (1,001), White men (2,923), White women (1,048); Maximum total days incarcerated: total sample (3,381), Native American men (3,381), Native American women (2,745), Latinos (1,444), Latinas (882), Black men (1,348), Black women (1,002), White men (2,923), White women (1,048)

Average length of stay among those with 1 incarceration is just the total length of stay for their one incarceration

The median total days incarcerated for all incarcerations during the study period among the total sample was 3 (IQR 1, 23). Compared to other racial/ethnic and sex groups, Native American men (median=9, IQR 2, 46) and Latinos (median=10, IQR 1, 50) had higher median total days incarcerated. Average length of stay increased by number of incarcerations for all racial/ethnic and sex groups (Table 3).

Time to first re-incarceration

Between the initial incarceration and first re-incarceration, the majority of individuals were released on their own recognizance (21%), released on bond (17%), completed their sentence (18%), were released to a third party (13%), immediately released (8%), had other agency charges (6%), released to the department of corrections (3%), escaped (<1%), or other (14%). After release from the index incarceration, 40% of individuals were re-incarcerated. After 30 days, 4.1% had been re-incarcerated at the Coconino County Detention Facility (Figure 3). By 6 months, 16% had reentered and by 1 year, 23% had been re-incarcerated. By 18 months, 27% had been re-incarcerated. Men and women were re-incarcerated similarly (Figure 3). The youngest group (18–24-year olds) were re-incarcerated later and less frequently than individuals in older age groups (Figure 3). Native American and White individuals were re-incarcerated sooner than Latinx and Black individuals (Figure 3).

figure 3.

Time (in days) from First Release from the Coconino County Detention Facility to First Re-Incarceration (2001-2018), N = 75,203

DISCUSSION

Among our study of 75,203 individuals incarcerated in the Coconino County Detention Facility from 2001–2018, about 40% were incarcerated more than once while 4% of individuals were incarcerated more than ten times. However, the number of incarcerations varied by race/ethnicity and sex. Our finding of 40% re-incarceration differed compared to previous work among HIV-infected adults leaving jail.19,20 Fu et al. found that 30% of their sample were re-incarcerated within 180 days20 while White et al. found that over 70% of their sample were re-incarcerated (within a 2,677 day follow-up period).19 The finding of a lower proportion of re-incarcerated individuals may stem from a larger, less restricted sample size with up to 17 years of follow up. Both studies restricted their small sample to HIV-infected adults. Our sample included all individuals, 18 years and older, who were booked into the Coconino County Detention Facility.

Of the 40% re-incarcerated, most were re-incarcerated within 18 months. This time between re-incarceration is shorter compared to previous studies.19–21 Local determinations, statutes, rules, and policies may impact population makeup, immigration laws, and law enforcement aggressiveness. These determinants may affect re-incarceration rates that our data are unable to answer. Additionally, we were not able to determine the true initial incarceration. Because our data were limited to only the Coconino County Detention Facility between January 1, 2001 and May 30, 2018, a full incarceration history was not available. Incarcerations occurring in Coconino County prior to or following the study period as well as information from other counties and states are unavailable. Thus, identifying an initial, prior, or subsequent incarceration outside of Coconino County poses challenges, particularly if individuals move from the County. This may be especially true in a transient city such as Flagstaff, AZ, which is on the Interstate-40 corridor and includes a university with a large student population. Although we cannot identify who among the individuals incarcerated are students, 28% of our population was 18–24, comparable to national estimates of jail incarceration among this age group.5 Additionally, Native Americans incarcerated at Coconino County Detention Facility had higher rates of re-incarceration compared to other racial/ethnic groups. This may indicate a less transient Native American population and stronger residential ties to Coconino County compared to individuals of other racial/ethnic backgrounds. We also were not able to censor by death or migration out of the county. Future work could include National Death Index data for more informative censoring. We additionally did not censor the 3.0% of individuals who were released to the Department of Corrections (prison). Individuals may be re-incarcerated in the Coconino County Detention Facility following release from a prison stay.

Compared to other studies,9,22 the median length of stay in the jail was shorter at 1 day. Previous studies found that the median length of stay among individuals with felony charges in 59 counties was 7 days9 and 48 hours among felony and non-felony detainees released from 88 county jails.22 Unlike previous studies, our findings were from one rural, county jail and therefore may not be generalizable to state and national populations. Generalizability may be limited, but our findings were similar to 88 county jails that are located in counties with populations greater than 200,000 persons22 and may be generalizable to populations with high rural populations of Latinx and Native American residents.

It is important to recognize that incarceration is distributed unevenly across US population, disproportionately affecting minority populations.2,3,6,23 Previous work indicates racial disparities exist in re-incarceration among individuals incarcerated in jail.21 The disparities of incarceration by race/ethnicity was not lost in our findings. Although the Coconino County population only includes 1.5% Black, 28% Native American, and 14% Latinx,24 a higher proportion of individuals incarcerated at Coconino County Detention Facility from 2001 to 2018 were racial/ethnic minorities (Black (4%), Native American (33%), Latinx (16%)). Additionally, number of incarcerations, length of stay, and time to first re-incarceration varied by race/ethnicity. Native American men had the highest proportion of individuals re-incarcerated. Native, Latinx, and Black men had the highest total and average length of stays. In addition, Native Americans has shorter time between incarcerations compared to other race/ethnic groups. Previous work indicates a higher percentage of Black individuals released from jail are more likely to be re-incarcerated,20,21 re-incarcerated sooner,19 and have longer length of stays21 compared to their White counterparts. Although our findings indicate racial/ethnic disparities, Black and Latinx men and women were re-incarcerated less and later compared to White individuals. Differences in results may stem from differences in the underlying population distribution. Over the study period, only 4.2% of individuals incarcerated in the Coconino County Detention Facility were Black. Although our sample may not be representative of the US and may not be comparable to previous work, we were uniquely positioned to describe incarcerations by race/ethnicity, particularly among Native Americans and Latinx in a rural region of Arizona.

Our study population included all adults 18 years and older who had an index incarceration at the Coconino County Detention Facility from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2016 with follow up incarcerations through May 30, 2018. Although we have an almost complete sample of incarcerations, iLEADS was not created to collect data for research purposes. Similar to administrative claims data from hospitals and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, there are limitations to our administrative data. First, there is a lack of documentation and information about quality of data. When an individual is booked into the Coconino County Detention Facility, a multitude of information must be collected in a short amount of time. Other than information that may be pertinent for the jail, variables such as marital status, occupation, and education were missing at a significant rate. These data may be informative for research purposes.

More than 20 million (9.0%) adults in the US currently or have been incarcerated.3–5 However, characteristics of jail stays are heterogeneous and have been largely left out of public health research. A better understanding of who is incarcerated and how often re-incarceration occurs can help design analyses that assess health outcomes of those in jails and inform future public health interventions and policy. Our study is an early step in shaping an understanding of jail incarceration as an exposure for future public health and epidemiologic research. Following such research may lead to a target group of high-risk individuals based on incarceration history to focus necessary health policy changes and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the Coconino County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC), with especial thanks to Toby B. Olvera (CJCC Coordinator), Matthew Figueroa (Commander, Coconino County Detention Facility), Elizabeth C. Archuleta (Coconino County Supervisor, District 2), Sarah Douthit (Chief Probation Officer, Coconino County), and James Driscoll (Coconino County Sherriff) as well as the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council board for their dedication and support during this project; James Brett (Program Coordinator for the Coconino County Detention Facility) for key access to data and advice; Scott George (Information Technology for the Coconino County Detention Facility) for building the database; and William Wilson and Clint Baker (Systems Administrators Sr., Northern Arizona University) for IT support.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The Health Disparities in Jail Populations study is funded by The NARBHA Institute, Flagstaff Arizona, with additional support from the Northern Arizona University (NAU) Center for Health Equity Research (CHER) and the NAU Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative (NIH/NIMHD U54, Grant #NIH U54MD012388).

Footnotes

DATA ACQUISITION

Data and code are not available. The data required creation of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and a complex data sharing protocol. The MOU includes data acquisition and data protection procedures that are IRB and HIPAA approved.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PloS one. 2009;4(11):e7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan O, Kuramoto F, Emmet W, Stange JL, Nobunaga E. The impact of the Affordable Care Act on behavioral health care for individuals from racial and ethnic communities. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2014;13(1–2):139–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai JR, Befus M, Mukherjee DV, Lowy FD, Larson EL. Prevalence and Predictors of Chronic Health Conditions of Inmates Newly Admitted to Maximum Security Prisons. J Correct Health Care. 2015;21(3):255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahalt C, Bolano M, Wang EA, Williams B. The state of research funding from the National Institutes of Health for criminal justice health research. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(5):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minton TD, Zeng Z. Jail inmates at midyear 2014. NCJ. 2015;241264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drucker E A plague of prisons: The epidemiology of mass incarceration in America. New Press, The; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langan PA, Levin DJ. Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Fed Sent R. 2002;15:58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaulding AC, Perez SD, Seals RM, Hallman MA, Kavasery R, Weiss PS. Diversity of release patterns for jail detainees: implications for public health interventions. American journal of public health. 2011;101(S1):S347–S352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massoglia M Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(1):56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BA, Goodwin JS, Baillargeon J, Ahalt C, Walter LC. Addressing the aging crisis in US criminal justice health care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(6):1150–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. American journal of public health. 2002;92(11):1789–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niveau G Prevention of infectious disease transmission in correctional settings: a review. Public Health. 2006;120(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public health reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trotter RT II, Camplain R, Eaves ER, et al. Health Disparities and Converging Epidemics in Jail Populations: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(10):e10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Leading causes of death by age group, United States: In. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene M, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Metzger L, Williams B. Older adults in jail: high rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health & justice. 2018;6(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich JT, Neely JG, Paniello RC, Voelker CC, Nussenbaum B, Wang EW. A practical guide to understanding Kaplan-Meier curves. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;143(3):331–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White MC, Marlow E, Tulsky JP, Estes M, Menendez E. Recidivism in HIV-infected incarcerated adults: influence of the lack of a high school education. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85(4):585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu JJ, Herme M, Wickersham JA, et al. Understanding the revolving door: individual and structural-level predictors of recidivism among individuals with HIV leaving jail. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(2):145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung H, Spjeldnes S, Yamatani H. Recidivism and survival time: Racial disparity among jail ex-inmates. Social Work Research. 2010;34(3):181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Assessment of sexually transmitted diseases services in city and county jails--United States, 1997. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1998;47(21):429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander M The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. American FactFinder. Vol 3: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2018. [Google Scholar]