Summary

Bioactive molecules can pass between microbiota and host to influence host cellular functions. However, general principles of interspecies communication have not been discovered. We show here in C. elegans that nitric oxide derived from resident bacteria promotes widespread S-nitrosylation of the host proteome. We further show that microbiota-dependent S-nitrosylation of C. elegans Argonaute protein (ALG-1)—at a site conserved and S-nitrosylated in mammalian Argonaute 2 (AG02)—alters its function in controlling gene expression via microRNAs. By selectively eliminating nitric oxide generation by the microbiota or S-nitrosylation in ALG-1, we reveal unforeseen effects on host development. Thus, the microbiota can shape the post-translational landscape of the host proteome to regulate microRNA activity, gene expression and host development. Our findings suggest a general mechanism by which the microbiota may control host cellular functions, as well as a new role for gasotransmitters.

Keywords: C. elegans, development, miRNA, microbiome, S-nitrosylation

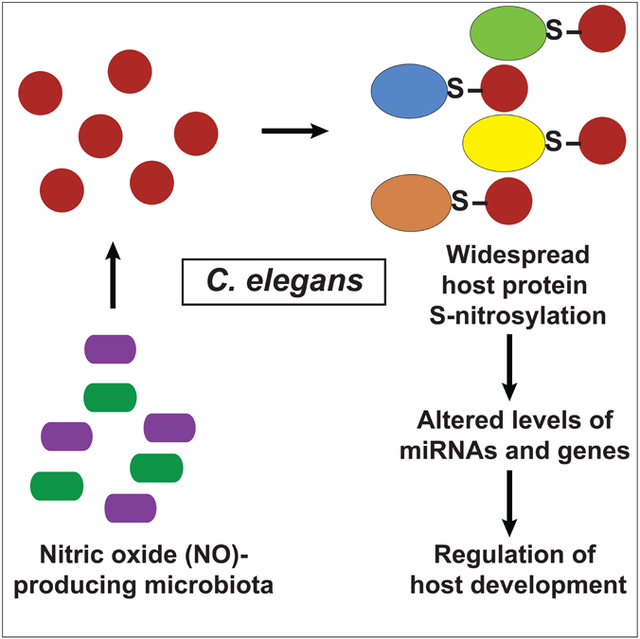

Graphical Abstract

In Brief:

Microbiome-derived metabolites cause widespread post-translational modifications of host proteins with myriad functional consequences

Introduction

The bodies of most multicellular organisms provide a habitat for simpler microorganisms. The relationships of these resident microorganisms with the host animal range from parasitic to mutualistic (Blum, 2017; Cho and Blaser, 2012; Lee and Hase, 2014). Bioactive molecules can pass between the microbiota and the host with the potential to alter the fitness and health of both (Donia and Fischbach, 2015; Shapira, 2017). Elucidating the precise consequences of the microbiota on host function remains challenging because of the extreme heterogeneity of microorganisms resident in an animal, as well as the diverse properties of microbiota-derived molecules. Nonetheless, cellular communication is subject to general principles and signaling modalities. We therefore considered the possibility that the microbiota employs general strategies to regulate host cellular function.

The nematode C. elegans provides a tractable and elegant system for investigating the interplay between commensal bacteria and a host animal. In the laboratory, these nematodes are co-cultured on a consistent and pure diet of their food source, bacteria (and can also be made microbe free (Stiernagle, 2006)). In spite of being bacterivores, C. elegans have been shown to harbor intact bacteria in the gut that persist throughout the life of the animal (Berg et al., 2016; Dirksen et al., 2016; Felix and Duveau, 2012). Furthermore, it is clear from observations made in C. elegans isolated from both native and experimental habitats (including decaying fruits and vegetables, soil and compost) that the composition of the nematode microbiota is relatively insulated from environmental variation (Dirksen et al., 2016). Several studies have confirmed the functional importance of the microbiota on nematode physiology, notably lifespan (Cabreiro et al., 2013; Gusarov et al., 2013; Han et al., 2017; Heintz and Mair, 2014); however, the molecular mediators and mechanisms governing interspecies communication are largely unknown.

We theorized we could test the idea of a general mechanism of interspecies signaling by identifying proteome-wide changes in the host organism that are mediated by commensal bacteria. Nitric oxide (NO) mediated S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues provides a unique opportunity to test these ideas. It is estimated that ~70% of the universal proteome may be subject to post-translational regulation by S-nitrosylation (~7000 proteins reported to date), primarily at conserved sites (Abunimer et al., 2014), including effects on protein activity, stability, localization and interactions. S-nitrosylation thus operates across phylogeny (Anand et al., 2014; Seth et al., 2012) as a fundamental mechanism for regulating protein function, thereby controlling diverse physiology including motility, metabolism, energy utilization and lifespan (Hess and Stamler, 2012; Rizza et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018; Seth et al., 2018; Stomberski et al., 2018). Notably, many members of the native nematode microbiota (e.g., B. subtilis) are capable of producing NO (Adak et al., 2002; Gusarov et al., 2013), which has also been linked to C. elegans lifespan (Gusarov et al., 2013), and similar benefits of microbiota-derived NO on human health have been confirmed more recently (Hezel and Weitzberg, 2015; Vanhatalo et al., 2018; Whitlock and Feelisch, 2009).

Bacterial NO production is primarily dependent on the activity of two enzymes: NO synthase (NOS) and/or nitrate reductase (NarG) (Adak et al., 2002; Ji and Hollocher, 1988; Ralt et al., 1988). These enzymes are therefore prime candidates for mediating protein S-nitrosylation in C. elegans. Importantly, C. elegans are known to be reliant on commensal bacteria as a source for NO (Gusarov et al., 2013). We reasoned, therefore, that microbe-generated NO might potentially influence nematode physiology broadly via modification of C. elegans proteins. Here, by selectively eliminating NO generation in the microbiota and its S-nitrosylation of nematode proteins, we reveal a general mechanism by which the microbiota post-translationally shapes the proteome of its host to regulate cellular function and physiology. More specifically, our studies reveal thousands of proteins targeted by interspecies S-nitrosylation, exemplified by bacterial S-nitrosylation of C. elegans Argonaute proteins to regulate RISC assembly, miRNA activity and developmental timing.

Results

Microbiota-derived nitric oxide mediates protein S-nitrosylation in C. elegans

To test the hypothesis that nematode S-nitrosylation is mediated by microbiota-derived NO, we plated microbe-free nematodes (C. elegans, N2 strain) on lawns of either wild-type (WT) B. subtilis, or a mutant strain containing a deletion of the bacterial NOS (Δnos). We then isolated total protein from worms at the L4/young adult stage and specifically pulled down S-nitrosylated proteins using resin-assisted capture (SNO-RAC) (Forrester et al., 2009). We observed large-scale and robust S-nitrosylation of the C. elegans proteome that was dependent on bacterial NOS (Figures 1A and1B). We obtained similar findings in experiments where the nematodes were plated on WT E. coli or mutant E. coli harboring a deletion of nitrate reductase (ΔnarG) (Figure 1C and D), which generates NO under anaerobic conditions (Seth et al., 2012) such as are known to be present in nematode gut (Minning et al., 1999). S-nitrosylation of host proteins by dissimilar microbiota under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions suggests that S-nitrosylation may be observed in multiple habitats. Approximately 1000 S-nitrosylated host proteins were identified by mass spectrometry (MS) of worms cultured on WT B. subtilis (Table S1). KEGG analysis demonstrated an enrichment of proteins involved, for example, in energy utilization and cellular metabolism, recapitulating findings in mammalian cells (Raju et al., 2015) (Table S2). The proteome of a metazoan, therefore, can be dramatically altered at the post-translational level by commensal bacteria, in particular via S-nitrosylation.

Figure 1. Microbiota-derived NO mediates widespread protein S-nitrosylation in C. elegans, including Argonaute proteins.

(A) Robust S-nitrosylation of the C. elegans proteome by B. subtilis. Silver stain of endogenous SNO-proteins (following SNO-RAC) was performed on lysates harvested from C. elegans grown either on wild type B. subtilis 1A1 (WT) or Δnos B. subtilis (Δnos), treated with (SNO-proteome; left panel) or without (Control; middle panel) ascorbate (Asc). Coomassie blue stain of total proteome loading controls (right panel). Gels are representative of three experiments. (B) Quantification of gels in A (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (C) S-nitrosylation of the C. elegans proteome by E. coli. Silver stain of endogenous SNO-proteins (following SNO-RAC) was performed on lysates harvested from C. elegans grown either on wild type E. coli(WT) or ΔnarG E. coli (ΔnarG), and either treated with (SNO-proteome; left panel) or without (Control; middle panel) ascorbate. Coomassie blue stain of total proteome loading controls (right panel). Gels are representative of three experiments. (D) Quantification of gels in C (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (E) S-nitrosylation of C. elegans ALG-1 by NO derived from B. subtilis NOS. ALG-1 immunoblot following SNO-RAC (+Asc) from lysates as in A. -Asc serves as a control (Forrester et al., 2007). Total ALG-1 loading control is also shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (F) Quantification of gels in E (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (G) S-nitrosylation of C. elegans ALG-1 by NO derived from E. coli nitrate reductase NarG. ALG-1 immunoblot following SNO-RAC (+Asc) from lysates as in A. Total ALG-1 loading control is also shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (H) Quantification of gels in G (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (I) Robust S-nitrosylation of the C. elegans proteome by small amounts of B. subtilis: effect of titration. Coomassie blue stain of endogenous SNO-proteins (following SNO-RAC) was performed on lysates harvested from C. elegans grown either on wild type (WT) B. subtilis 1A1 (100%) or Δnos (Δnos) B. subtilis 1A1 (0%) or a mixture comprising 10% WT and 90% Δnos; the SNO-proteome, -Asc control and total proteome loading controls are shown (left to right, respectively). Gels are representative of three experiments. (J) Quantification of gels in I (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (K) S-nitrosylation of C. elegans ALG-1 by small amounts of B. subtilis NOS. Immunoblot of endogenous ALG-1 (following SNO-RAC) was performed on lysates harvested from C. elegans grown on wild type (WT) B. subtilis 1A1 (100%) , Δnos (Δnos) B. subtilis 1A1 (0%), or mixtures comprising 10% WT and 90% Δnos, 25% WT and 75% Δnos, 50% WT and 50% Δnos, and 75% WT and 25% Δnos. A lower exposure autoradiography film is shown (middle). Total ALG-1 loading control is also shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (L) Quantification of gels in J (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (M) Bacterial colony forming units (CFU) per C. elegans from worms cultured with either WT B. subtilis (WT) or Δnos B. subtilis (Δnos). See also Tables S1 and S2.

The widespread modification of the host proteome by its microbiota begs the question of whether these modifications can impact host cellular function(s). The Argonaute-related protein ALG-1 is among the nematode proteins of well-defined function that we identified as being S-nitrosylated in nematodes co-cultured with B. subtilis (Table S1). The highly conserved ALG-1 protein mediates the post-transcriptional down regulation of mRNAs via the microRNA pathway (Grishok et al., 2001, Vasquez-Rifo et al., 2012). As C. elegans has been a classic model for the study of microRNA-dependent gene regulation, including numerous cellular functions, we investigated the possibility that protein modification by resident microbes could regulate host cellular processes via microRNAs. MicroRNA pathways in C. elegans classically regulate the timing of postembryonic cell fate progression and determination across several cell lineages; this regulation is essential to normal development of the animal and ultimately entry into adulthood. As ALG-1 has established functions in worm development (Vasquez-Rifo et al, 2012), we asked whether microbiota-derived NO might play a role in microRNA-mediated temporal control of gene expression and development. We used an ALG-1 specific antibody to first verify directly that ALG-1 was S-nitrosylated by commensal bacteria. Using SNO-RAC, we demonstrated that ALG-1 was robustly S-nitrosylated in situ and that S-nitrosylation was markedly attenuated in nematodes grown on Δnos B. subtilis (Figures 1E and 1F). S-nitrosylation of ALG-1 was also seen in nematodes plated on E. coli and host S-nitrosylation was eliminated with ΔnarG E. coli (Figure 1G and H). Thus, S-nitrosylation of C. elegans ALG-1 is mediated by NO derived from the microbiota. That ALG-1 is robustly S-nitrosylated by two different microbes with propensity to generate NO in different amounts and under different conditions, strongly suggests physiological relevance.

To further strengthen the case for physiological relevance, we plated C. elegans on lawns of mixed WT and Δnos B. subtilis, with increasing amounts of WT B. subtilis to determine the minimal percentage of NO-producing bacteria required for detectable interspecies S-nitrosylation. Even a 10% WT B. subtilis mixture was sufficient to achieve protein S-nitrosylation (Figure 1 I and J) and 25% WT B. subtilis achieved saturating levels of ALG-1 S-nitrosylation, making it highly likely that in native habitats, the C. elegans microbiota produce NO at levels sufficient to mediate interspecies S-nitrosylation (Figure 1K and L). In order to test for differences in bacterial abundance within worms plated on WT or Δnos B. subtilis, we quantified bacterial colony formation from homogenized single worms, using methods that allow gut bacteria to remain viable. Supernatant from unlysed worms was used as control (to correct for external contamination). Similar numbers of intact bacteria were found in worms cultured on WT vs. Δnos B. subtilis (Figure 1M), consistent with a previous report (Gusarov et al., 2013). Collectively, our results raise the tantalizing idea that nematodes may regulate access to NO by varying food intake (amount of bacteria), food source (bacterial species) or oxygen tension in their environment (e.g., depth in soil).

S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins at a phylogenetically-conserved cysteine

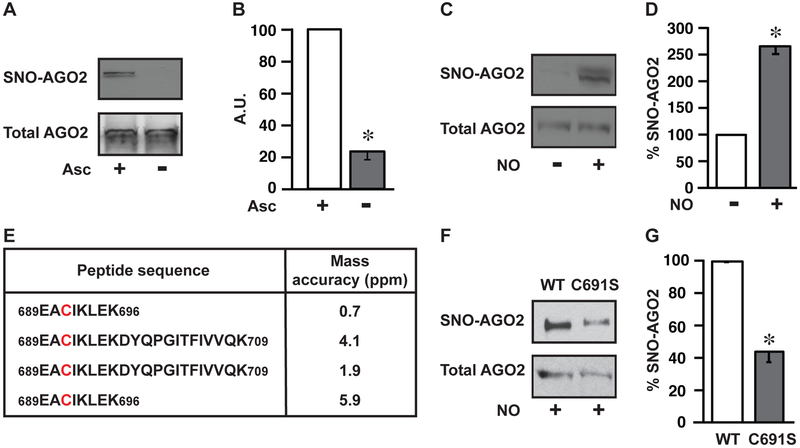

To determine the effect of S-nitrosylation on Argonaute function, we first sought to identify the Cys residue undergoing modification. Since C. elegans can be recalcitrant to biochemical manipulation and because Argonaute proteins are highly conserved, we focused initially on human AGO2 (arguably the primary mammalian Argonaute activity) (Liu et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2004). Notably, we observed that AGO2 was endogenously S-nitrosylated in HEK293 cells (Figures 2A, 2B and S1A), which express low basal levels of endothelial NOS (Ozawa et al., 2008) (Figure S1B), and that exogenous NO increased AGO2 S-nitrosylation (Figures 2C, 2D and S1A). Thus, the molecular machinery of mammalian translational repression is modified by NO (as it is in the nematode) and provides a tractable system for biochemical analysis.

Figure 2. AGO2 Cys691 is a primary locus of S-nitrosylation.

(A) Endogenous S-nitrosylation of human AGO2. Immunoblot for AGO2 in HEK293 cells following SNO-RAC ± ascorbate control (Asc). AGO2 loading control is shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (B) Quantification of gels in A (n=3, ± SEM). A.U., arbitrary units. *, differs from +Asc by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (C) S-nitrosylation of AGO2 by exogenous NO. Immunoblot for AGO2 in HEK293 cells following SNO-RAC ± NO donor (CysNO). Total AGO2 loading control is shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (D) Quantification of gels in C (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from –CysNO by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (E) Locus of S-nitrosylation in AGO2. Peptides containing the Cys691 site of S-nitrosylation identified by LC-MS/MS from 4 independent experiments. SNO-Cys were labelled with iodoacetamide using switch methodology (Jaffrey and Snyder, 2001). Conditions are as in C. (F) Validation of AGO2-Cys691 S-nitrosylation by site-directed mutagenesis. Immunoblot for SNO-AGO2 in HEK293 cells transfected with either WT-AGO2 (WT) or Cys691 mutant AGO2 (C691S) after treatment with CysNO, as in C. Total AGO2 loading control is shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (G) Quantification of gels in F (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). See also Figure S1.

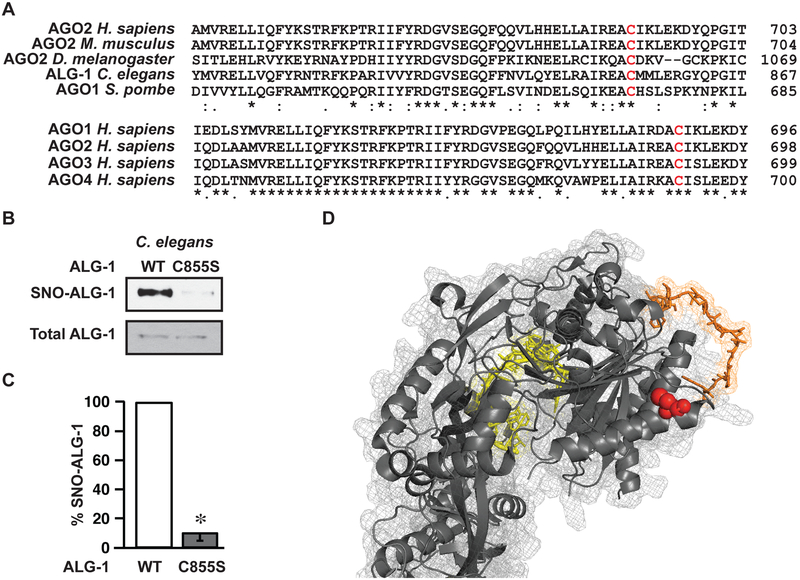

AGO2 has 22 cysteine residues, many of which are predicted by GPS-SNO analysis (a computation algorithm for SNO-site identification) (Xue et al., 2010) to be putative S-nitrosylation sites. Hence, we undertook an MS-based approach to identify the specific sites of S-nitrosylation. We incubated purified, recombinant human AGO2 with the NO donor S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO; 100 μM), followed by pull-down using an AGO2 antibody. The samples were then subjected to a modified switch assay (Jaffrey and Snyder, 2001), in which NO groups are replaced by iodoacetamide (IAA), and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Notably, only one cysteine residue, Cys691, was consistently identified as being S-nitrosylated in AGO2 (Figure 2E). We then confirmed that Cys691 was a primary locus of NO modification by transfecting HEK293 cells with either WT AGO2 or a mutant AGO2 in which Cys691 was replaced by serine (C691S). Upon treatment with CysNO (100 μM), WT AGO2 was strongly S-nitrosylated while the signal was much weaker in the C691S mutant (Figures 2F and 2G). Interestingly, Cys691 is highly conserved across phylogeny, including human Argonaute isoforms (AGO1-4) as well as nematode ALG-1 (Figure 3A). Given the conserved site for S-nitrosylation (Cys855 in ALG-1), we used genome editing to generate a nematode with the C855S point mutation. ALG-1 C855S animals showed markedly lower levels of ALG-1 S-nitrosylation in tissues as compared to their WT counterparts; S-nitrosylation was in fact virtually undetectable in mutant ALG-1 animals (Figures 3B and 3C). Thus, Cys855/Cys691 represents a phylogenetically conserved site of S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins, and the C855S nematode is essentially refractory to ALG-1 S-nitrosylation.

Figure 3. S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins at a phylogenetically-conserved Cys.

(A) Site of S-nitrosylation in human AGO2 is conserved in C. elegans ALG-1. Amino acid sequence alignment of H. sapiens AGO2 and its orthologs from different eukaryotic species (top), and alignment of human AGO1-4 homologs (bottom). Human AGO2 SNO-site Cys691 is conserved in eukaryotes (shown in red). (B) ALG-1-C855S mutant C. elegans is refractory to endogenous S-nitrosylation. Immunoblot for SNO-ALG-1 (immunoblot for ALG-1 following SNO-RAC) in lysates from WT or ALG-1-C855S C. elegans. Total ALG-1 loading control is shown. Gel is representative of three experiments. (C) Quantification of data in B (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT ALG-1 nematodes by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (D) 3D crystal structure of AGO1 in complex with GW182 hook motif (orange) showing the conserved SNO-site cysteine 689 (analogous to AGO2 Cys691) in red and the miRNA-mRNA complex in yellow.

S-nitrosylation inhibits the essential interaction of Argonaute-2 with GW182

We next questioned whether S-nitrosylation of AGO2 altered its gene silencing activity. AGO2 is part of a multi-protein assembly that includes GW182 family proteins. The interaction between AGO2 and GW182 is required for silencing of mRNA targets (Lian et al., 2009). An inspection of a recent structure of human AGO1 with endogenous RNA and the hook motif of GW182 revealed that the conserved Cys resides within the PIWI domain, adjacent to the putative interaction site with GW182 (Figure 3D) (Elkayam et al., 2017; Pfaff et al., 2013). By contrast, the conserved Cys was distant from the RNA binding pocket, which argues against a role in mediating RNA contacts (Figure 3D).

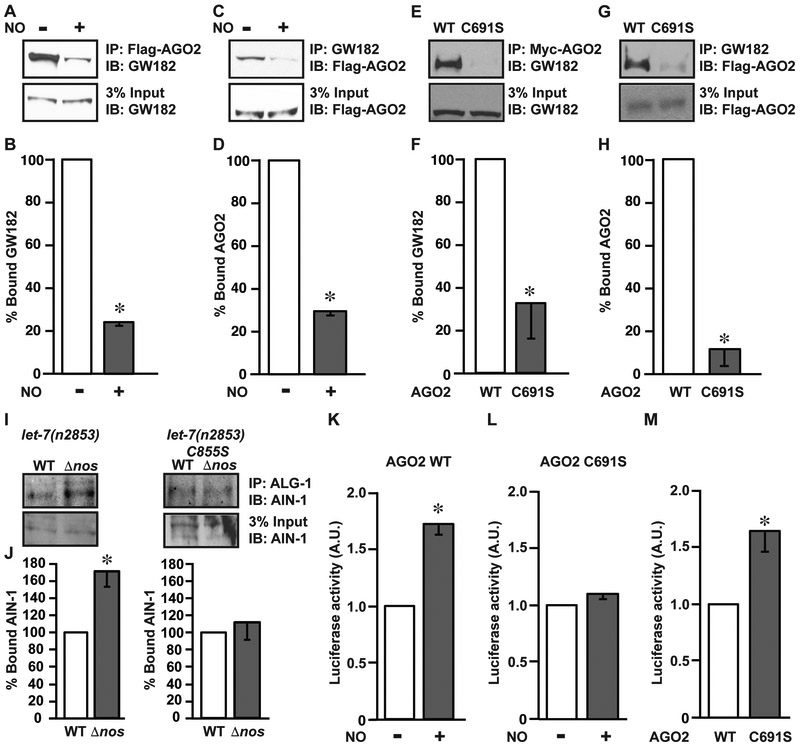

We therefore hypothesized that S-nitrosylation may alter the binding of AGO2 to GW182. In co-immunoprecipitation experiments, WT AGO2 was physically associated with GW182, and this association was strongly inhibited by addition of NO (DETA-NO; see Methods) (Figures 4A-4D). Mutation of the S-nitrosylation site to a serine (C691S) markedly decreased the interaction between AGO2 and GW182 (Figures 4E-4H), but hardly altered the ability of AGO2 to interact with either microRNA or mRNA (Figure S2A). This is consistent with other AGO2 mutations that affect its binding to GW182 proteins but do not change microRNA binding (Jannot et al., 2016; Kuzuoglu-Ozturk et al., 2016). Further, exogenously transfected siRNA, whose activity is independent of GW182 proteins, demonstrated similar knockdown efficiency in HEK293 cells expressing either WT FLAG-AGO2 or C691S FLAG-AGO2 (Figure S3). An inhibitory effect of S-nitrosylation on the interaction between endogenous ALG-1 and AIN-1 (the C. elegans GW182 ortholog) was also demonstrated by immunoprecipitations from WT or C855S-ALG-1 worms cultured on either WT or Δnos B. subtilis (Figures 4I and 4J). In addition, NO inhibited the interaction between endogenous AGO2 and GW182 in cultured mammalian cells (Figure S2B). Thus, based on reciprocal co-immunoprecipitations of Argonautes and GW182 proteins in worms and mammals in the presence and absence of NO, all of which show reduced interaction following NO treatment but where this NO effect is also lost after mutation of AGO2-C691S, we conclude that S-nitrosylation of AGO2/ALG-1 inhibits their interaction with GW182 proteins. We also conclude from these data that S-nitrosylation mediated by microbiota may regulate Argonaute/GW182 protein interactions in situ, and that mutation of the Cys site of NO modification (C691 or its C. elegans ortholog at 855) mimics the effect of S-nitrosylation, as it often does in other systems (Ozawa et al., 2008). Thus, Cys691/C855 needs to be in its native (un-nitrosylated) state to interact efficiently with GW182 proteins. Altering this conserved residue by either S-nitrosylation or mutation leads to decreased interaction with GW182, perhaps by disrupting hydrogen bonding interactions or altering the charge distribution at the interface of the two proteins (Marino and Gladyshev, 2010; Raju et al., 2015).

Figure 4. Conserved cysteine nitrosylation site in Argonaute proteins mediates an essential interaction with GW182 proteins.

(A-D) Nitric oxide inhibits the interaction between GW182 and AGO2. (A) Immunoblot for GW182 following immunoprecipitation of AGO2 in the absence or presence of the NO donor DETA-NO (NO). HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-AGO2 and immunoprecipitation was carried out with αFLAG antibody. Gels are representative of three experiments. (B) Quantification of gels in A (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from –NO by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (C) FLAG immunoblot, following immunoprecipitation of endogenous GW182 with GW182 antibody. Conditions are as in A. Gels are representative of three experiments. (D) Quantification of gels in C (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from –NO (−DETA-NO) by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (E-H) Cys 691 in AGO2 is required for interaction with GW182. (E) GW182 immunoblot following immunoprecipitation of AGO2. HEK293 cells were transfected with either Myc-AGO2 (WT) or Myc-C691S mutant AGO2 (C691S). Immunoprecipitation was performed with antibody against Myc. (F) Quantification of gels in E (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT-AGO2 by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (G) FLAG immunoblot following immunoprecipitation of GW182 as in C. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with either FLAG-WT-AGO2 or FLAG-AGO2-C691S. Gels are representative of three experiments. (H) Quantification of gels in G (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT-AGO2 by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (I) AIN-1 immunoblot from either let-7(n2853) WT ALG-1 or C855S-ALG-1 animals following IP with ALG-1 antibody, using lysates from animals co-cultured on WT B. subtilis (WT) orΔnos B. subtilis (Δnos). Total AIN-1 input is shown. (J) Quantification of gels in I (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT B. subtilis by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (K-M) Inhibition by NO of AGO2 activity mediated through S-nitrosylation of Cys691. (K) miRNA activity assays in HeLa cells using a luciferase reporter containing seven let-7 miRNA binding sites upon co-transfection with AGO2 WT in the absence or presence of DETA-NO (NO). Values presented are luciferase readings normalized for GFP. *, differs from –NO by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (L) miRNA activity reporter assays as in K upon co-transfection of the AGO2-C691S mutant in either the absence or presence of NO. (M) miRNA activity reporter assays as in K and L, upon co-transfection with either AGO2 WT or AGO2 C691S mutant in the absence of NO (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). See also Figure S2-S3.

S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins inhibits miRNA-mediated gene silencing

Our data predict that S-nitrosylation of Cys691 should interfere with AGO2 silencing of mRNA targets. To test this, we used a validated reporter assay (Mayr et al., 2007) where the luciferase gene is flanked by the 3’ UTR of HMGA2 mRNA (a known target of let-7 microRNA) containing either seven WT or seven mutated let-7 binding sites. These reporters were then co-transfected with WT or C691S mutant AGO2, in the absence or presence of NO. Consistent with our hypothesis, WT AGO2 repressed its target poorly in the presence of NO (manifest by higher expression of luciferase mRNA), whereas NO had little effect on mutant C691S AGO2 activity (Figures 4K and 4L). Furthermore, mutant C691S AGO2 activity, as measured by luciferase mRNA repression, was weaker than WT AGO2 activity (Figure 4M) and the relative difference between WT and C691S mutant AGO2 activity was comparable to that of WT AGO2 activity in the absence and presence of NO (Figure 4M vs. Figure 4K). Taken together, these findings identify a potential molecular mechanism for microbiota-dependent microRNA-based regulation of gene silencing, whereby exogenous NO mediated S-nitrosylation of a single conserved cysteine in Argonaute proteins disrupts interaction with GW182, and ultimately inhibits miRNA mediated repression of target mRNAs.

Microbial S-nitrosylation of ALG-1 influences C. elegans developmental timing via microRNA activity

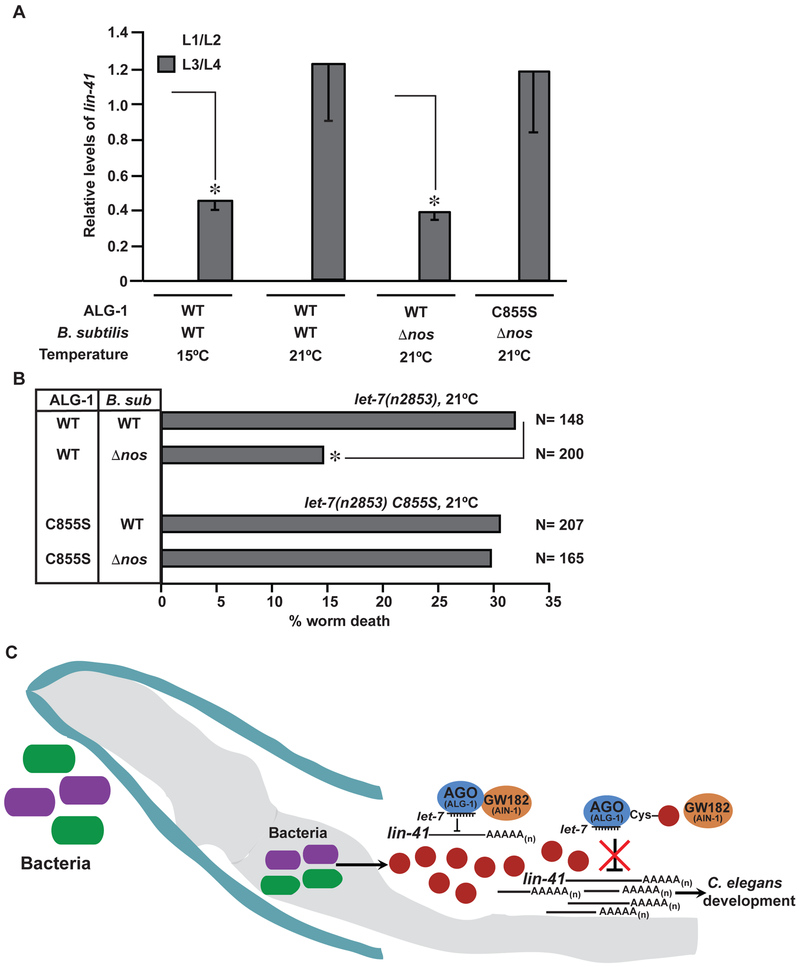

To establish a functional role for microbiota-mediated S-nitrosylation, we examined the effect of ALG-1 S-nitrosylation on miRNA-mediated regulation of developmental timing in C. elegans. The let-7 miRNA is conserved between C. elegans and humans, and has been shown to be essential for the advancement of adult cell fate programs in C. elegans (Pasquinelli et al., 2000; Reinhart et al., 2000). In particular, during vulval morphogenesis, the let-7 miRNA temporally targets lin-41 mRNA upon entry of the animal into the late larval stages (Vella et al., 2004); failure to target lin-41 leads to vulval rupture and animal death. Notably, ALG-1-C855S animals (with impaired AIN-1 binding) were difficult to generate and invariably failed to propagate on the WT background, possibly consistent with lethality seen in worms with ALG-1 mutations that disrupt AIN-1 binding (Jannot et al., 2016).

Let-7 is loaded onto both ALG-1 and ALG-2 proteins, which share developmental functions and targets (Vasquez-Rifo et al., 2012). Because ALG-1-C855 is also conserved in ALG-2, this redundancy of proteins and potential redundancy of regulation may buffer the effects of NO and protect from developmental defects (predictably, N2 C. elegans fed on either WT or Anos B. subtilis were similarly capable of let-7 mediated lin-41 silencing at a later larval stage (L3/L4) (Figure S4A and S4B)). Subtler measures of let-7 activity in C. elegans have been assisted by development of sensitizing mutations. We employed the let-7(n2853) temperature sensitive mutant, which fortuitously allowed for C855S propagation. The let-7(n2853) animal is known to experience nearly 100% lethality due to vulval bursting at the non-permissive temperature of 25°C but none at the permissive temperature of 15°C (Table S3) (Reinhart et al., 2000). While let-7(n2853) mutants at 15°C demonstrated nearly WT levels of lin-41 repression, mutants incubated at semi-permissive 21°C were incapable of let-7 mediated lin-41 repression at late larval stages (Figure 5A and as previously shown (Engels et al., 2012; Vella et al., 2004)). Notably, feeding with Anos B. subtilis at 21 °C fully rescued the developmental stage-specific lin-41 repression. Moreover, in the C855S mutant lacking the ALG-1 S-nitrosylation site, the rescue of lin-41 repression mediated by eliminating microbe-derived NO was abolished (Figure 5A). These results strongly suggest that gene repression during development is regulated by microbiota-mediated S-nitrosylation of ALG-1.

Figure 5. Microbe initiated S-nitrosylation of ALG-1 influences C. elegans developmental timing via microRNA activity.

(A) B. subtilis-derived NO inhibits miRNA activity through modification of Cys855 in ALG-1. qPCR analysis of lin-41 repression in let-7(n2853) worms at late developmental stages (L3/L4). Values are presented relative to lin-41 mRNA levels at their respective early developmental stages (L1/L2), which have been normalized to 1. *, differs from their respective lin-41 mRNA levels at L1/L2 stage by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). Data is representative of three independent experiments (n=3, ± SEM). (B) miRNA mediated regulation of developmental timing is dependent on microbiota-derived NO modification of Cys855 in ALG-1. Vulval bursting scored by plotting percent worm death in let-7(n2853) animals. N = number of worms. *, differs from let-7(n2853) incubated with B. subtilis (B. sub) (p=0.003) by Chi square test with Bonferroni correction. (C) Model depicts microbiome mediated regulation of host development via S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins. nos, Nitric oxide synthase; narG, Nitrate reductase.

We reasoned that lethal vulval rupture of let-7(n2853) mutants, secondary to perturbations in late larval stage-specific miRNA repression of gene expression, namely lin-41, would represent a consistent and quantifiable functional readout of the effect of the microbiota on host development. These mutants held at non-permissive temperatures (25°C) exhibit lethality consequent to vulval bursting during the larval-to-adult transition, as well as severe gonadal defects (Ecsedi et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2003; Reinhart et al., 2000; Slack et al., 2000; Vella et al., 2004). We scored vulval bursting at the intermediate temperature of 21°C, at which these sensitized animals experienced a ~30% bursting rate when cultured with WT B. subtilis. Remarkably, when incubated with Δnos B. subtilis, the bursting rate was 15%, a full two-fold reduction (p = 0.003) (Figure 5B). This protective effect was independent of levels of mature let-7 miRNA in late larval stages, which were similar in both groups (Figure S4C). Additionally, no such difference in lethality was observed in C855S let-7(n2853) animals cultured either on WT or Δnos B. subtilis (Figure 5B), and C855S let-7(n2853) mutants displayed lethality that was virtually identical to let-7 (n2853) animals (i.e., WT ALG-1) cultured on WT B. subtilis. Thus our data indicate that commensal bacteria directly modify C. elegans ALG-1 via S-nitrosylation to alter host gene expression and thereby impact host developmental timing and phenotypic outcome (Figure 5C).

Discussion

Descriptions of host-microbe interactions have centered on exchange of metabolites and unusual molecules (Dodd et al., 2017; Olson et al., 2018; Sampson et al., 2016). We explored the possibility that interspecies communication may involve universal mechanisms of transduction, and describe a general strategy for cross-species communication whereby the microbiota widely modifies the host proteome using the ubiquitous effector NO. Interspecies S-nitrosylation may thus provide a general mechanism by which the microbiota exerts control over host cellular signaling, raising the specter of widespread influence over host functions by commensal bacteria. Most notably, we have discovered that the host microRNA machinery is regulated by microbial NO through a locus conserved among Argonaute proteins. Interspecies S-nitrosylation thereby regulates host gene expression via microRNAs, opening new avenues of investigation. Further, we describe the functional consequences of microbiota-control of animal physiology in regulation of vulval development. The possibility that commensal bacteria may also influence mammalian development merits consideration given the conservation of pathways involved.

There is growing appreciation of the multiple sources of NO that may influence animal fitness, including NOSs, cytochrome c oxidase, nitrate reductases and nitrate-rich foods (Castello et al., 2006; Hess and Stamler, 2012; Kozlov et al., 1999; Lundberg et al., 2009). Irrespective of its source, NO is converted in situ into bioactive S-nitrosothiols that convey NO bioactivity and mediate S-nitrosylation of proteins (Pawloski et al., 2001; Pinheiro et al., 2015; Seth et al., 2018; Stomberski et al., 2018). In this model, dedicated signal transduction pathways, not the source of NO, determine cellular responses (Seth et al., 2018; Stomberski et al., 2018). This can be best appreciated in the blood pressure-lowering effect of NO generated from gastric byproducts, despite the ubiquitous presence of NOS throughout the circulatory system (Pinheiro et al., 2016; Vanhatalo et al., 2018). S-nitrosothiols in the stomach can evidently access vascular tissues throughout the body to regulate end-organ effects independently of NO produced locally (McKnight et al., 1997; Pinheiro et al., 2015; Stamler et al., 2012). Pathways that convey self-versus nonself-derived NO bioactivity and accordingly partition cellular signals into uniquely tailored responses remain to be elucidated. This is a matter of importance as microbial NO contributes far more to the host nitrosoproteome than previously imagined.

C. elegans represents a notable example of an animal where NO is not derived primarily from NOS (Gusarov et al., 2013). While alternative sources of endogenous NO evidently exist (Figure 1), C. elegans’ reliance on commensal bacteria (Gusarov et al., 2013) has allowed for investigation, at unprecedented molecular and mechanistic detail, into microbiota-regulated host signaling—from the source of the bioactive signaling molecule in B. subtilis and E. coli to its function-regulating modifications of host proteins. The potential implications of these data for mammalian biology are tantalizing, as the mouth and skin microbiota in humans are known to represent functional sources of NO that can affect cardiovascular homeostasis and host energy utilization (Bryan et al., 2017; Vanhatalo et al., 2018; Whitlock and Feelisch, 2009). In addition, gut-derived NO has been shown to S-nitrosylate plasma albumin (Pinheiro et al., 2016), establishing the principle that NO derived from food and enteric origins can promote S-nitrosylation of host proteins. Given the potential generality of our findings, including the conservation of Argonaute S-nitrosylation sites and of S-nitrosylation sites generally (Abunimer et al., 2014), it seems plausible that human microbiome (and food)-derived NO might influence gene regulation via miRNAs and host cellular functions broadly.

Post-translational modifications are critical determinants of Argonaute protein function. As central effectors of the miRNA pathway, Argonaute proteins are increasingly recognized as subject to diverse modifications. For example, Argonaute protein stability is regulated by hydroxylation of proline residues, while S387 phosphorylation facilitates RISC formation by increasing AGO2 interaction with cofactors like GW182 to enhance gene repression (Horman et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2008; Rajgor et al., 2018). Our data represent the first report of S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins in regulating the miRNA pathway. By contrast to serine phosphorylation, we find that S-nitrosylation of AGO2 serves to destabilize its association with GW182 leading to reduced miRNA activity. The site of S-nitrosylation in AGO2 is conserved in C. elegans ALG-1, preventing its association with the GW182 ortholog AIN-1 in situ. Thus, microbial regulation of the host miRNA machinery is a physiological occurrence in living animals. Taken together, our findings suggest that S-nitrosylation of Argonaute proteins may transduce both microbiota- and host-derived signals to regulate gene expression.

The striking influence of the microbiota on organ developmental timing (through modulation of lin-41 activity; Figure 5) may reflect host-microbe co-evolution. Studies in human twin pairs reveal the impact of host genetics on the microbiome (Arumugam et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2014). Although the fidelity of any specific microbial partner-host relationship is highly variable, C. elegans isolated from their native habitats retain a core bacterial community with several NO producing species; hence host responsiveness to bacterially-derived NO may have conferred a survival benefit, perhaps through effects on development (Berg et al., 2016; Dirksen et al., 2016). B. subtilis, which we study, is found among the natural microbiota of C. elegans and although E. coli itself is not, other bacteria that, like E. coli, use nitrate reductase to generate NO are found naturally in the worm microbiome, such as members of the phylum Actinobacteria (Dirksen et al., 2016). Whether C. elegans seek out such bacteria or are colonized by NO-producing microbes, and whether they may regulate their own exposure to NO (e.g., by varying the amount or species of bacteria they consume or the oxygen tension in their environment through their depth in soil) remains to be seen. Further studies in this area may provide insight into the fascinating possibility of hosts intervening in their own development or survival fitness through inclusion or exclusion of bacteria within their microbiomes.

The broad spectrum of proteins we observed in the nematode nitrosoproteome (of which we list ~1000 using screening methodology that provides only a partial picture) implies that wide-ranging host physiology, beyond miRNA control of developmental timing, may be regulated by commensal bacteria. As one example, it has been reported that the increase in C. elegans longevity mediated by commensal NO requires the mammalian FOXO orthologue DAF-16 (Gusarov et al., 2013), although the molecular mechanism is not known. We find that DAF-16 is robustly S-nitrosylated by microbial NO under standard laboratory conditions (growth on E. coli) (Figure S5), suggesting that the effects of bacterial NO on lifespan may be mediated by transcriptional regulation. Further, a recent study has observed that P. aeruginosa-generated NO contributes to avoidance behavior that is dependent on the SNO-regulating activity of C. elegans protein thioredoxin-1 (TRX-1), although the SNO-targets have yet to be identified (Hao et al, 2018). Notably, we find thioredoxin-like 1 (TXL-1) and thioredoxin reductase (TRXR-1) in our C. elegans SNO-proteome (Table S1). More generally, it may be fruitful to consider whether signaling by gasotransmitters as a rule (including NO, H2S and CO) represents a general strategy for interspecies communication involving modification of host proteomes (Gadalla and Snyder, 2010). Thus, we propose that microbiota-dependent modification of host proteomes by gasotransmitters—exemplified by robust interspecies S-nitrosylation—may represent a general mechanism by which the resident microbiota control host functions. We also speculate that intake of dietary sources of NO in mammals might have physiologic consequences during early developmental stages.

STAR Methods

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to the lead author, Jonathan S. Stamler (jonathan.stamler@case.edu).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

C. elegans strains, maintenance and preparation

Wild-type N2 Bristol and mutant let-7(n2853) strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA). N2 nematodes were maintained and prepared using standardized methods including nematode growth medium supplemented with 1 mM arginine, and age synchronization by hypochlorite (Koo et al., 2017). All strains were out-crossed at least 3 times with wild-type nematodes. The let-7(n2853) strains were maintained at 15°C, and were incubated at 15°C, 21°C or 25°C in specific experiments as indicated.

Bacterial strains

B. subtilis strain 1A1 (strain 168) and the isogenic Δnos, were obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (BGSC) at The Ohio State University. The Δnos strain had been described previously (Koo et al., 2017). These bacteria were grown in LB medium at 37°C. Erythromycin (20 μg/ml) was added to the media when growing the Δnos B. subtilis. E. coli strain BW25113 WT and ΔnarG were procured from the KEIO collection from the Coli Genetic Stock Center (CGSC) at Yale University. E. coli were grown in LB medium at 37°C.

Cell lines

HEK293 cells (female) and HeLa cells (female) procured from ATCC (Manassas, Virginia) were already authenticated using STR profiling. Cultured cells were grown in 1X DMEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to a final concentration of 10% plus 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Method Details

Reagents

S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO) was prepared as previously described (Forrester et al., 2007). DETA-NONOate (DETA-NO) was obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI) and was prepared and used per manufacturer’s instructions. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies for Western blotting included mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), goat anti-DAF-16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), polyclonal rabbit anti-His-tag and monoclonal rabbit anti-AGO2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-ALG-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), GW182 antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), c-myc antibody (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) and DAF-16 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). SilverQuest™ silver staining kit was procured from Invitrogen™ (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Imperial™ Protein Stain was from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). AIN-1 antibody was a gift from John K. Kim (Johns Hopkins University)

Plasmids

To express 6xHis tagged recombinant proteins, the amplified AGO2 cDNA was cloned into pET21b vector (Novagen, Merck Biosciences) and sequenced (pET21b-AGO2-His). The sequences of the primers are given in the Key Resources Table. FLAG-AGO2, Hmga2 3’UTR WT luciferase and Hmga2 3’UTR m7 luciferase were obtained from Addgene and their identifiers are provided in the Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse anti-FLAG M2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F1804 RRID:AB_262044 |

| Rabbit anti-His-tag | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2365S RRID:AB_2115720 |

| Myc-antibody | R&D systems | Cat#AF3696 RRID:AB_2282405 |

| Rabbit anti-AGO2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2897 RRID:AB_2096291 |

| ALG-1 antibody | Invitrogen | Cat#PA1-031 RRID:AB_2539852 |

| Rabbit anti-GW182 (for immunoblotting) | Novus Biologicals | Cat#NBP1-57134 RRID:AB_11008641 |

| Goat anti-DAF16 antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#SC-9229 RRID:AB_671895 |

| eNOS antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#SC-654 RRID:AB_631423 |

| β-actin antibody | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A1978 RRID:AB_476692 |

| Anti-GW182 antibody (for immunoprecipitation) | Novus Biologicals | Cat#NBP1-28751 RRID:AB_2207020 |

| GAPDH antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab181602 RRID:AB_2630358 |

| β-arrestin2 antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3857 RRID:AB_2258681 |

| AIN-1 antibody | Alessi et al., 2015(Gift of John K. Kim, Johns Hopkins University) | N/A |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | Life Technologies | Cat#15240-062 |

| DMEM | Life Technologies | Cat#11965-092 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F4135 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| B. subtilis 1A1 | BGSC, Ohio State University | BGSCID: 1A1 |

| B. subtilis 1A1 (∆nos) | BGSC, Ohio State University | BGSCID: BKE07630 |

| E. coli strain BW25113 WT | CGSC, Yale | CGSC#7636 |

| E. coli strain BW25113 ∆narG | CGSC, Yale | CGSC#11789 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| DETA-NONOate | Cayman Chemicals | Cat#82120 |

| Purified Cas9 | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0386 |

| tracrRNA | Dharmacon | Cat#U-002005 |

| DPTA-NONOare | Cayman Chemicals | Cat#82110 |

| QIAzol lysis reagent | QIAGEN | Cat#79306 |

| IP lysis buffer | Thermo Scientific | Cat#87788 |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablets | Roche | Cat#04693159001 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| SilverQuest silver staining kit | Invitrogen | Cat#LC6070 |

| Imperial Protein Stain | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#24615 |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Promega | Cat#E1910 |

| pre-cast 4-20% SDS-PAGE gels | Bio-Rad Laboratories | Cat#3450033 |

| Protein A/G Agarose | Pierce, ThermoScientific | Cat#20421 |

| Lipofectamine® 2000 | ThermoScientific | Cat#11668027 |

| Lipofectamine RNAi Max | Invitrogen | Cat#13778075 |

| SuperSignal® West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate | ThermoScientific | Cat#34095 |

| PolyJet reagent | SignaGen Laboratories | Cat#SL100688 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Structure of human Argonaute-1 in complex with the hook motif of human GW182 | Elkayam et al., 2017 | PDB:5W6V |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293 Cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1573 |

| HeLa cells | ATCC | Cat#CCL-2 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans wild isolate (C. elegans var Bristol) | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Cat#N2 |

| C. elegans let-7(n2853) | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Cat#MT7626 |

| C. elegans C855S let-7(n2853) | This study | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Human Ago2 cloning F: 5’GACTGAACATATGTACTCGGGAGCCGGCCCCGCACTTGCACC 3’ | This study | Life Technologies |

| Human Ago2 cloning R: 5’TATCGTACAAGCTTAGCAAAGTACATGGTGCGCAGAGTGTCTTGG 3’ | This study, Life Technologies | N/A |

| Ago2 C691S F: 5’ GCTGGCCATCCGTGAGGCCAGTATCAAGC 3’ | This study, Life Technologies | N/A |

| Ago2 C691S R: 5’ GCTTGATACTGGCCTCACGGATGGCCAGC 3’ | This study, Life Technologies | N/A |

| TracerRNA: 5’AACAGCAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUGGCACCGAGUCGGUGCUUUU 3’ | This study, Dharmacon | N/A |

| CrRNA alg-1: 5’ TGAGCTTCGCGCGATTCGCG 3’ +5’ GUUUUAGAGCUAUGCUGUUUUGUUU 3’ | This study, Dharmacon | N/A |

| CrRNA dpy-10: 5‘ GCUACCAUAGGCACCACGAG 3’ +5’ GUUUUAGAGCUAUGCUGUUUUG 3’ | This study, Dharmacon | N/A |

| Non-targeting control siRNA pool | ThermoScientific: | Cat#D-001810-10-05 |

| β-arrestin2 specific siRNA pool Mission esiRNA | Sigma-Aldrich: | Cat#EHU069991 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pET21b | Novagen | Cat#69741 |

| pET21b-AGO2-His | This study | N/A |

| FLAG-AGO2 | Lian et al., 2009 | Addgene Plasmid #21538 |

| Hmga2 3’UTR WT luciferase | Mayr et al., 2007 | Addgene Plasmid #14785 |

| Hmga2 3’UTR m7 luciferase | Mayr et al., 2007 | Addgene Plasmid #14788 |

| pcDNA myc tagged AGO-2 | Liu et al, 2005(Gift of Greg Hannon, CSHL) | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| PyMol 2.0 | Pymol | https://pymol.org/2/ |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Other | ||

C. elegans Bursting Assays

Let-7(n2853) worms possessing either WT-ALG-1 or C855S-ALG-1 were synchronized by hypochlorite and grown at either 15°C, 21°C or 25°C (Stiernagle, 2006). The number of animals dying through vulval rupture were counted and compared against the number of surviving animals (Broughton et al., 2016).

C. elegans CRISPR Genome Editing

Genome editing was performed using CRISPR/Cas9 as described (Paix et al., 2015). Briefly, purified Cas9 (NEB), tracrRNA, dpy-10 and alg-1 crRNA, and repair templates were incubated at 37°C for ten minutes for in vitro assembly, then loaded for injection. Worms were screened for rollers, bred to separate dpy-10 from alg-1 edits, and sequenced. TracrRNA was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). The sequences of the tracrRNA and repair template sequences are provided in the Key Resources Table.

C. elegans lysis

All steps were performed at 4°C unless stated otherwise.

For protein extraction:

Worms were lysed in 1 ml of HEN buffer (100 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM Neocuproine) containing protease inhibitors by repeatedly snap freezing in liquid nitrogen/thawing in 37°C water bath. Worms in HEN buffer were sonicated, employing four 15 second pulses at setting 4 of the VirSonic sonicator (VirTis, SP Industries, Warminster, PA). After sonication, the lysate was visualized under the microscope to confirm worm rupture.

For RNA extraction:

Worms were washed four times in M9 buffer, then resuspended in 1 ml of QIAzol reagent. They were then subjected to at least two repeated cycles of snap freeze/thaw in liquid nitrogen/37°C water bath. Subsequently, they were disrupted at room temperature in TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using a stainless steel bead in each sample tube for 2 minutes at 30 Hz. Total RNA was extracted in QIAzol per manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of S-nitrosylated proteins by SNO-RAC (SNO Resin-Assisted Capture)

S-nitrosylated proteins were isolated by SNO-RAC as described (Forrester et al., 2009). In brief, cells were lysed in HEN buffer additionally containing 1% NP-40, 50 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors. Free cysteines were blocked with S-Methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS). After acetone precipitation and multiple 70% acetone washes, proteins were re-suspended in HEN buffer containing 1% SDS. 50 μl thiopropyl Sepharose 6B resin (GE, Chicago, IL) and 50 mM sodium ascorbate were added, followed by rotation in the dark for 4 hr at room temperature. Following multiple washes, the bound proteins were eluted in 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol. Following separation on reducing pre-cast 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), individual SNO-proteins were detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies (anti-FLAG, anti-myc, anti-ALG-1, anti-AGO2, anti-GW182) or the gel was stained using the SilverQuest™ silver staining kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or Imperial™ Protein Stain (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), per manufacturer instructions.

Colony Forming Unit Assays

Individual C. elegans were lysed in a bead-beater (BioSpec Products Bartlesville, OK) at the highest setting, using 1 mm Zirconia beads (BioSpec Products Bartlesville, OK) with 5 1-min cycles of beating alternating with 1-min cooling intervals, followed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 1 minute at 4°C. The supernatant was then dilution plated on LB plates and the resulting colonies were counted after an overnight incubation at 37°C.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using the QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per manufacturer’s instructions. 2 μg of RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI), per manufacturer’s instructions. Cleanup after the DNAase treatment was performed using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and the RNA was finally resuspended in nuclease free water. The cDNA was prepared using the 5X iScript™ RT Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) per manufacturer’s instructions. Gene specific primers were used for real-time PCR in an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus instrument using either 2X iQ SYBR green supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) for detecting mRNAs or specific Applied Biosystems™ TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for detecting microRNAs. For RNA from C. elegans the expression of Y45 mRNA in each sample was used to normalize the expression of lin-41 mRNA, while the levels of U18 RNA was used to normalize the expression of the let-7 micro RNA. For RNA from cultured human cells, U6 RNA and 5S rRNA were used to normalize the expression for microRNAs and mRNAs, respectively. Fold-change in expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method. Real-time PCR primers for lin-41 and Y45 from C. elegans have been validated previously (Broughton et al., 2016).

Purification of 6xHis tagged recombinant proteins

The AGO2 cDNA was cloned into the pET21b (Novagen) vector to introduce a 6xHis tag at its C-terminus. Transformed overnight bacterial cultures were sub-cultured into 3L of LB medium at 4% volume. At OD600 of 0.4, cultures were induced by addition of 100 μM IPTG and grown further for 4 hr at 25°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500 x g for 15 min. For every 1 L of culture, bacterial pellets were lysed in 2 mL of 2X Cellytic B cell lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2 mL of buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/ml lysozyme, 5 μg/ml DNase and 1 mM PMSF. To aid the lysis, rotation at room temperature was performed for 30 min and then the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 12 min. The collected lysate was diluted 4-fold in a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole and incubated at room temperature for 2 hr with rotation with 1.5 ml of Ni-NTA agarose (pre-equilibrated with the 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl buffer). This slurry was then poured into empty PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Beads were then washed with 100 ml of 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl buffer containing 20 mM imidazole. Elution was done using 20 ml of 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl buffer with 250 mM imidazole, with 1 ml fractions collected. 15 μl from each collected fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing the pure AGO2 protein were pooled and stored at −80°C in 30% glycerol.

Mass spectrometric identification of AGO2 S-nitrosylation site

200 μg of purified 6xHis-tagged AGO2 was further purified by immunoprecipitation using 10 μg of AGO2 specific antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) at 4°C overnight with rotation, in a final volume of 600 μl of elution buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl buffer with 250 mM imidazole, after which 30 μl of protein A/G Sepharose (Pierce®, ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) was added and the samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The protein A/G Sepharose-antibody complexes were pulled down by centrifugation at 1000 g in a swinging bucket rotor. Following five washes with the IP/lysis buffer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) at 1000 x g for 1 min each, the bound proteins were eluted using Gentle Elution buffer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA). The eluate was then treated with 100 μm CysNO for 30 minutes, in a final volume of 300 μl of sodium-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). They were then precipitated using 3X volume of acetone in the presence of 100 μg of BSA carrier protein. After 3 washes with 70% acetone, the pellet was re-suspended in a final volume of 600 μl HEN buffer containing 1% SDS and 100 mM N-ethylmaleimide and was incubated at 20°C for 25 minutes. The samples were then re-precipitated with acetone and washed 3 times with 70% acetone to remove excess maleimide. Pellets were then resuspended in 800 μl of HEN buffer with 1% SDS and were divided in two equal aliquots based upon volume. One aliquot was reduced in the presence of 500 mM ascorbate and 500 mM IAA, while the other aliquot was treated the same way except without the addition of ascorbate. The samples were then passed through a 50 kDa size cut off filter (Amicon®, Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA) and run on a 4-20% polyacrylamide gel, followed by staining with Imperial™ reagent, as described earlier.

Gel bands were sliced and washed with 50% acetonitrile/50% ammonium bicarbonate, while vortexing at room temperature for more than 5 hrs. After removal of washing buffer, 200 μl of 100% acetonitrile was added to dehydrate gel bands for 10 min. Gel pieces were completely dried by vacuum spin dryer at room temperature for 10 min. Dry gel pieces were incubated with 200 μl of 10 mM DTT for 45 min at 37°C. After removal of DTT solution, 200 μl of 55 mM N-methylmaleimide was added to gel pieces at 37°C for 45 min. 200 μl of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 200 μl of 100% acetonitrile were used alternatively to wash the gel bands (vortexing time=10 min for each wash). Gel pieces were then dried by vacuum spin dryer at room temperature for 10 min and incubated with enzyme solution containing 500 ng sequencing grade trypsin in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer at 37°C overnight. Supernatant containing protein digests was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube. Peptides were extracted by incubating the gel pieces in 60% acetonitrile containing 5% formic acid for 30 minutes with constant vortexing, followed by sonication for 15 min. This was repeated three times and the extracts were pooled in a 1.5 ml tube and dried to completion in a speed-vac. The dried peptides were then reconstituted by 0.1% formic acid and subjected to LC/MS (liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry) analysis.

A UPLC (Waters, Milford, MA) coupled with an Orbitrap Elite hybrid mass spectrometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) was used to separate and identify peptides. Peptides were loaded to a 5-cm X 75-μm Pico Frit C18 column (New Objective, Woburn, MA) and emitted to the mass spectrometer by a 10 μm nanospray emitter (New Objective, Woburn, MA). A linear chromatography gradient from 1% to 40% organic phase, using 100% acetonitrile as organic phase and 0.1% formic acid as inorganic phase, was used to separate peptides for 60 minutes at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. All mass spectrometry data were acquired in positive ion mode. A full scan at resolution of 120,000 was conducted followed by 20 tandem MS/MS scans. CID cleavage mode was performed at normalized collision energy of 35%.

MS data were searched against the human AGO2 protein sequence and its reversed sequence as a decoy. Massmatrix database was used for data searching (Xu and Freitas, 2007, 2009; Xu et al., 2009). Modifications including oxidation of methionine and labeling of cysteine (NMM, NEM or IAA) were used as variable modifications for performing the search. Trypsin was selected as an in silico enzyme to cleave proteins after Lys and Arg. Precursor ion searching was within 10 ppm mass accuracy and product ions within 0.8 Da for CID cleavage mode. After identification by software, manual matching of each product ions in mass spectrometry was applied for confirmation.

Mass spectrometric identification of C. elegans SNO-proteome

All liquid reagents used were HPLC quality grade. Protein digestion was performed with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer by incubation overnight at 37°C. For MS analysis the data were collected by a high-resolution MS2 method using an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MS) coupled to a Proxeon EASY-nLC 1000 liquid chromatography (LC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The run sequence used high-resolution measurements for MS1 and MS2 in the Orbitrap. The capillary column was a 100 μm inner diameter microcapillary column packed with ~35 cm of Accucore C18 resin (2.6 μm, 150 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated in 240 minute acidic acetonitrile (AcN) gradients by LC prior to MS injection. The scan sequence began with a MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis; resolution 120,000; mass range 400–1400 Th). MS2 analysis in the Orbitrap (resolution was 15,000 at 200 Th) followed collision-induced dissociation (CID, CE=35) with a maximum ion injection time of 200 ms and an isolation window of 0.7 Da. Peptides were searched using a SEQUEST-based in-house software against the C. elegans proteome database with a target decoy database strategy. Spectra were converted to mzXML using a modified version of ReAdW.exe. Searches were performed using a 50 ppm precursor ion tolerance for total protein level profiling. The product ion tolerance was set to 0.03 Da. Oxidation of methionines and modification of cysteines (+15.9949146221 Da and +45.987721 Da, respectively) were set as variable modifications. Peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were identified, quantified and collapsed to a 1% peptide false discovery rate (FDR) and then collapsed further to a final protein-level FDR of 1%.

NO donor treatment and lysis of cultured cells.

Transfected HEK293 or HeLa cells were cultured at 37°C in 15 cm tissue culture-treated dishes. They were then treated with either 500 μM DETA-NOate (t1/2 = 20 hr) for 16 hours, 100 μM CysNO for 10 min, or 200 μM dipropylenetriamine (DPTA)-NONOate (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) for 6 hours. Cells were washed once with DPBS without calcium chloride and magnesium chloride from Gibco® (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated on ice for 10 minutes in IP lysis/wash buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with added EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). This was followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 minutes to collect the supernatant. The lysates were then used for immunoprecipitation experiments.

Immunoprecipitation experiments

For HEK293 cells, all steps were performed either on ice or in the cold room at 4°C. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with 3 mg of total lysate that was pre-cleared using a Pierce™ control agarose resin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), after which 10 μg of IP antibody was added, and samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with rotation. The next day, 30 μl of protein A/G Sepharose (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added and the samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The protein A/G Sepharose-antibody complexes were pulled down by centrifugation at 1000 g in a swinging bucket rotor. Following five washes with the IP lysis/wash buffer, the bound proteins were eluted at room temperature in glycine-HCL buffer, pH 3.5. The eluates were neutralized by adding 3 μl of 1M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and analyzed by western blotting. FLAG-AGO2 was a gift from Edward Chan (Addgene plasmid #21538) (Lian et al., 2009) and pcDNA myc tagged AGO-2 was a kind gift from Dr. Greg Hannon at CSHL (Liu et al, 2005).

For C. elegans, lysates were prepared at L4/young adult stage as described in Zanin et al., 2011. Briefly, synchronized worms at L4/young adult stage were washed with IP lysis buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), resuspended in a small volume of the same lysis buffer followed by snap-freezing in a dropwise fashion in liquid nitrogen leading to formation of beads, and then stored at −80°C. Lysates were prepared by grinding frozen worm beads in liquid nitrogen using a pre-chilled metal mortar and pestle, followed by sonication as described earlier under “C. elegans lysis”. Worm lysates were pre-cleared using a Pierce™ control agarose resin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with 20 μg of ALG-1 antibody for IP (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using 10 mg of total worm lysates, with rotation. All subsequent washing steps were carried out at 4°C and elution was carried out room temperature in glycine-HCL buffer, pH 3.5. Immunoblotting was performed using an AIN-1 antibody, which was a kind gift from Dr. John K Kim at Johns Hopkins University (Alessi et al., 2015).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The sequence of the primers used for mutagenesis is as given in the Key Resources Table.

Luciferase assays

0.5 × 105 cells/well Hela cells were plated in wells of 24 well dishes. They were transiently transfected the next day with 2 mg of either WT-AGO2 or C691S-AGO2, plus 100 ng of either Hmga2 3'UTR-WT luciferase (Luc-wt) or Hmga2 3'UTR-mutant7 luciferase (Luc-m7) control. 100 ng pMax-GFP was also co-transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency. Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine® 2000 transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Six hours after transfection, the NO donor DETA-NONOate (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) was added at 500 μM. The cells were harvested 24 hours post-transfection, using 1X Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Renilla luciferase activity was measured using the Renilla Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Veritas™ microplate luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA) and normalized to GFP readings measured using a BMG FluoStar Galaxy microplate reader. Hmga2 3’UTR WT luciferase (Luc-wt) and Hmga2 3’UTR m7 luciferase (Luc-m7) were gifts from David Bartel (Addgene plasmid # 14785 and # 14788, respectively) (Mayr et al., 2007)).

siRNA knockdown experiments

siRNA knockdown experiments were performed in HEK293 cells that had been plated in 6-well plates and transfected with the indicated plasmids using PolyJet reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD), following manufacturer’s instructions. The siRNA knockdowns were performed using either the β-arrestin2 specific siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or non-specific siRNA controls (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) with Lipofectamine RNAi Max from Invitrogen™ (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), following manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting

Lysates containing equal amount of protein were run on pre-cast 4-20% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) followed by transfer onto Nitrocellulose blotting membrane (GE Healthcare, UK) using the wet-transfer method. The membranes were then blocked with PBS-T containing 5% milk, followed by overnight incubation with specific antibody in 1X PBS containing 5% milk. After multiple washing with 1X PBS-T, the membrane was incubated for 1 hr with HRP-conjugated secondary from the appropriate species. After multiple washes with 1X PBS-T, the membrane was exposed to SuperSignal® West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) per manufacturer’s instructions, followed by autoradiography.

3D structure of AGO1

The published AGO1-GW182 hook 3D crystal structure (sPDB accession number 5W6V) (Elkayam et al., 2017) was downloaded from Protein Data Bank, https://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do. Open-sourced PyMOL 2.0 was used to locate and highlight the residue and regions of interest.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

ImageJ software was used for quantification of all Western blot and SDS-PAGE data. Data in figures are represented as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using KaleidaGraph Software. The p-values were typically calculated as repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic unless otherwise stated. In Figure 5B, vulval bursting was analyzed using the Chi square test for independence after adjusting for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni correction.

Additional statistical details for figures follow:

Figure 1B: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=17.33, p=0.0141, n=3. Figure 1D: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 41.96422, p= 0.00293, n=3. Figure 1F: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 89.6627, p= 0.00069, n=3. Figure 1H: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=20.75945, p=0.01037, n=3. Figure 1J: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 31.28324, p= 0.00501, n=3. Figure 1L: * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=266.81 , p<0.0001, n=3 (comparison of 0% and 100%). * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 55.7233 , p= 0.00172, n=3 (comparison of 10% and 100%). Figure 1M: One-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s post-test statistic, p= 0.9031. Figure 2B: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 217.8289, p=0.00012, n=3. Figure 2D: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=120.6861, p=0.00039, n=3. Figure 2G: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=31.07545, p=0.00508, n=3. Figure 3C: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=176.28259, p=0.0002, n=3. Figure 4B: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=1712.731, p<0.0001, n=3. Figure 4D: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=971.9214, p<0.0001, n=3. Figure 4F: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=16.36544, p= 0.01553, n=3. Figure 4H: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=158.462, p=0.00023, n=3. Figure 4J: *One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=18.12027, p=0.01309, n=3. Figure 4K: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=20.69549, p=0.0104, n=3. Figure 4L: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic, p=0.358. Figure 4M: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 18.05007, p=0.01317, n=3. Figure 5A: * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=249.4567, p < 0.0001, n=3 (at 15°C). * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=819.3025, p < 0.0001, n=3 (at 21°C). Figure 5B: * Chi square test for independence after adjusting for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni correction, p=0.003. Figure S2: * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=9858669.8, p < 0.0001, n=3 (levels of miR210). * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=15.90793, p= 0.0163, n=3 (levels of EFNA3 mRNA). Figure S3: * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 34.25134, p=0.0043, n=3 (in the AGO2-WT panel). * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=32.56632, p=0.0047, n=3 (in the AGO2-C691S panel). Figure S4A: * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=40349.24, p < 0.0001, n=3 (in C. elegans N2 on WT B. subtilis). * One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)= 2131.144, p < 0.0001, n=3 (in C. elegans N2 on Dnos B. subtilis). Figure S4B: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=1.453104, p=0.294, n=3. Figure S4C: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=0.260153, p=0.6369, n=3. Figure S5: One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test statistic F(1,5)=171.789, p=0.0002, n=3.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. S-nitrosylation of AGO2 by endogenous eNOS is enhanced by the NO donor DETA-NO in HEK293 cells. Related to Figure 2. (A) Immunoblot with αAGO2 antibody following SNO-RAC (+Asc) on lysates prepared from either untreated or DETA-NO (500 μM) treated cells. –Asc (control for SNO-RAC) and total AGO2 controls are also shown. (B) Immunoblot with αNOS3 (eNOS) antibody using increasing quantities of HEK293 cell lysates. Actin is shown as the loading control.

Figure S2. Effects of S-nitrosylation and SNO-site mutation on AGO2 activity and interactions. Related to Figure 4. (A) Mutation of AGO2 Cys691 has little effect on AGO2 interaction with microRNA or target mRNA in cultured cells. Relative levels of AGO2-associated miR210 and EFNA3 mRNA, measured by qPCR from HEK 293 cells that had been transfected either with FLAG-tagged WT-AGO2 (WT) or FLAG-tagged C691S-AGO2 (C691S), after immunoprecipitation of AGO2 with αFLAG antibody. *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (B) Nitric oxide inhibits the interaction between endogenous AGO2 and GW182. Immunoprecipitation of endogenous AGO2 and GW182 are shown in the left and right panels respectively, along with controls ± NO treatment.

Figure S3. Mutation of AGO2 C691 does not prevent AGO2-dependent silencing activity. Related to Figure 4. Comparable levels of β-arrestin2 knockdown are observed with β-arrestin2 specific siRNA (relative to non-specific siRNA control) in HEK 293 cells transfected with either WT FLAG-AGO2 or FLAG-AGO2-C691S. WT FLAG-AGO2 and FLAG-AGO2-C691S expression are shown; GAPDH loading control. *, differs from non-specific siRNA control by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure S4. Levels of lin-41 mRNA and let-7 miRNA at late larval stages (L3/L4) are similar in C. elegans N2 and let-7(n2853) strains cultured on WT B. subtilis (WT) vs. Δnos B. subtilis. Related to Figure 5. (A) Relative levels of lin-41 mRNA, as determined by qPCR, in C. elegans N2 worms at early (L1/L2) and late (L3/L4) developmental stages. Values are presented relative to lin-41 at L1/L2, which has been normalized to 1. *, differs from early larval stages (L1/L2) by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05). (B) qPCR analysis of let-7 miRNA expression in C. elegans N2 worms at early (L1/L2) and late developmental stages (L3/L4). Values are presented relative to let-7 (on WT B. subtilis diet) at L1/L2, which has been normalized to 1. (C) qPCR analysis of let-7 microRNA expression in C. elegans let-7(n2853) at early (L1/L2) and late (L3/L4) developmental stages at 21°C. Values are presented relative to let-7 (on WT B. subtilis diet) at L1/L2, which has been normalized to 1.

Figure S5. E. coli nitrate reductase mediates S-nitrosylation of C. elegans DAF-16. Related to Figure 5. (A) Robust S-nitrosylation of C. elegans DAF-16 by bacterial nitrate reductase NarG. DAF-16 immunoblot following SNO-RAC from worm lysates. Total DAF-16 loading control is also shown. Gels are representative of three experiments. (B) Quantification of gels in A (n=3, ± SEM). *, differs from WT by ANOVA with Dunnett’s test (p < 0.05).

Table S1. S-nitrosylated proteins in C. elegans. Related to Figure 1.

Table S2. KEGG analysis of C. elegans S-nitrosylated proteins. Related to Figure 1.

Table S3. Vulval rupture frequency of let-7 (n2853) worms co-cultured with NO-deficient bacteria at permissive (15°C) and non-permissive (25°C) temperatures. Related to Figure 5.

Highlights:

Microbiome-derived NO promotes widespread S-nitrosylation of the host proteome

Interspecies S-nitrosylation regulates miRNAs, gene expression and host development

Microbiota control host function by shaping the post-translational landscape

Acknowledgements

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper. This work was supported by R01-GM099921 to JSS, T32GM007250 and F30AG054237 to P.N.H, and R35HL135789 to MJ. We thank Marian Kalocsay for help with proteomic analyses, Precious J. McLaughlin for technical assistance, Divya Seth for valuable input and Thomas J. Sweet for help with RNA protocols. The AIN-1 antibody was a kind gift from John K. Kim at Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abunimer A, Smith K, Wu TJ, Lam P, Simonyan V, and Mazumder R (2014). Single-nucleotide variations in cardiac arrhythmias: prospects for genomics and proteomics based biomarker discovery and diagnostics. Genes 5, 254–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adak S, Aulak KS, and Stuehr DJ (2002). Direct evidence for nitric oxide production by a nitric-oxide synthase-like protein from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16167–16171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessia AF, Khivansaraa V, Hana T, Freeberga MA, Morescod JJ, Tud PG, Montoyee E, Yates JR III, Karpe X, and Kim JJ (2015). Casein kinase II promotes target silencing by miRISC through direct phosphorylation of the DEAD-box RNA helicase CGH-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E7213–E7222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Hausladen A, Wang YJ, Zhang GF, Stomberski C, Brunengraber H, Hess DT, and Stamler JS (2014). Identification of S-nitroso-CoA reductases that regulate protein S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18572–18577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, et al. (2011). Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473, 174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Stenuit B, Ho J, Wang A, Parke C, Knight M, Alvarez-Cohen L, and Shapira M (2016). Assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans gut microbiota from diverse soil microbial environments. ISME J. 10, 1998–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum HE (2017). The human microbiome. Adv. Med. Sci. 62, 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton JP, Lovci MT, Huang JL, Yeo GW, and Pasquinelli AE (2016). Pairing beyond the seed supports microRNA targeting specificity. Mol. Cell 64, 320–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan NS, Tribble G, and Angelov N (2017). Oral microbiome and nitric oxide: the missing link in the management of blood pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 19, 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabreiro F, Au C, Leung KY, Vergara-Irigaray N, Cocheme HM, Noori T, Weinkove D, Schuster E, Greene ND, and Gems D (2013). Metformin retards aging in C. elegans by altering microbial folate and methionine metabolism. Cell 153, 228–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello PR, David PS, McClure T, Crook Z, and Poyton RO (2006). Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell. Metab. 3, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, and Blaser MJ (2012). The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen P, Marsh SA, Braker I, Heitland N, Wagner S, Nakad R, Mader S, Petersen C, Kowallik V, Rosenstiel P, et al. (2016). The native microbiome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: gateway to a new host-microbiome model. BMC Biol. 14, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd D, Spitzer MH, Van Treuren W, Merrill BD, Hryckowian AJ, Higginbottom SK, Le A, Cowan TM, Nolan GP, Fischbach MA, et al. (2017). A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551, 648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donia MS, and Fischbach MA (2015). Human microbiota. Small molecules from the human microbiota. Science 349, 1254766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]