Abstract

Objectives:

To quantify platelet-neutrophil interaction by flow cytometry, in newborn cord blood, as a function of gestational age.

Rationale:

Little is known about platelet function markers in the newborn, and developmental variations in these markers are not well described.

Method:

Cord blood samples were obtained from 64 newborns between 23 and 40 weeks gestation. The neonates were grouped in 3 categories: preterm (< 34 weeks gestation, n = 21), late preterm (34 to < 37 weeks gestation, n = 22) and term (≥ 37 weeks gestation, n = 21). We monitored expression of P-selectin and formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates (PNA) by flow cytometry, while using ADP or thrombin receptor activator peptide (TRAP) as agonists.

Results:

PNA were significantly lower in preterm compared to term neonates after TRAP or ADP stimulations (11.5 ± 5.2% vs 19.9 ± 9.1%, p < .001 or 24.0 ± 10.1% vs 39.1 ± 18.2%, p = .008 respectively). The expression of P-selectin also tended to be lower in preterm neonates, with significant positive correlations between P-selectin expression and PNA formation.

Conclusions:

The potential formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates correlates with gestational age. This suggests that the development of functional competencies of platelets and neutrophils continues throughout gestation, progressively enabling interactions between them.

Keywords: Platelet activation, platelet function, neutrophil function, platelet neutrophil interaction, platelet, neutrophil, prematurity

INTRODUCTION

Platelets were first described in 1865 by Max Schultze [1]. Apart from their role in thrombus formation [2], platelets are now known to be involved in inflammation [3] angiogenesis [4], tissue repair and wound healing [5, 6], immunity [7, 8] and even cancer growth [9, 10]. In spite of these advances in platelet study, much remains to be learned about the developmental aspects of fetal and neonatal platelet function [11].

Previous platelet studies in the newborn tended to focus on clotting and bleeding times or platelet counts [12]. Such studies highlighted the increased risk of bleeding associated with thrombocytopenia in the newborn [12, 13]. Hemorrhagic morbidities such as intraventricular hemorrhage, pulmonary and gastrointestinal bleedings increase the risk of mortality especially in preterm newborns [14, 15]. However, many newborns who develop hemorrhagic disorders are not thrombocytopenic [16]. This implies that endogenously produced circulating platelets may not adequately provide the needed hemostatic support [17]. Therefore, neonatal platelet function studies are needed to further characterize the etiology and pathophysiology of these morbidities.

Neonatal platelets are said to be hypo-responsive to stimulation when compared to adult platelets [18–20]. They, however, appear to adequately protect the healthy newborn. Cord and peripheral blood samples from neonates were reported to have shorter clot formation times [21] and platelet function analyzer (PFA)-100 closure times (a measure of platelet adhesion and aggregation functions) [22]. Nevertheless, the coagulation system is increasingly impaired the earlier the gestation [23], and preterm neonates may not be fully protected.

A number of receptor and agonist specific responses were documented [19, 24], suggesting that all aspects of newborn platelet function are not necessarily hypo-responsive As such, P-selectin is a well-studied marker of platelet activation in both adults and newborns. However, the expression of this α-granule component may be lower in newborns [25, 24]. It is expressed on the platelet surface after activation and serves as a receptor for binding to leukocytes and endothelial cells [26, 27]. The formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates (PNA), however, was not explored in neonates even though recent studies in adults and animal models highlight such interactions [28, 29]. Neutrophil functions, such as a respiratory burst, trans-cellular production of eicosanoids, chemotaxis, extravasation into tissues and sites of infection, phagocytosis and NETosis, are enhanced upon interaction with platelets [30].

Developmental aspects of neonatal platelet activation and function still remain to be fully characterized. In this study, we compare the expression of P-selectin as a marker of platelet activation and the subsequent interaction of platelets with neutrophils in cord blood samples at different gestational ages. We hypothesize that these markers of platelet activation and function will be lower in preterm compared to term newborns. This information may be helpful in evaluating the risk assessment of some bleeding morbidities, especially those associated with prematurity.

METHODS

Subject and sample collection

Approval for the study was obtained from the Loma Linda University Health Institutional Review Board (LLUH IRB) prior to subject recruitment. Consents for the study were obtained from the mothers of neonates born at the Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital labor and delivery unit. Newborns with congenital disorders were excluded. Maternal and infant medical records were reviewed for subject characteristics such as age of the mother, gestational age and birth weight of the neonate, mode of delivery, gender and Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes. Cord blood samples were drawn from double-clamped umbilical cords into 2.7 ml 3.2% trisodium citrate Vacuette tubes (Greiner Bio-One) using a 21-gauge needle.

Flow cytometry analysis

Within 30 minutes of blood sampling, aliquots of whole blood were incubated at room temperature with fluorescently labelled monoclonal antibodies and either 20 μM Adenosine 5’-diphosphate (ADP, Sigma-Aldrich), 20 μM TRAP (thrombin-receptor activating peptide, Ser–Phe–Leu–Leu–Arg–Asn–Pro–Asn–Asp–Lys–Tyr–Glu–Pro–Phe, Sigma-Aldrich) or HEPES-Tyrode buffer (10 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.4 mM Na2HPO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.35% w/v bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4). Samples were further diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and then analyzed on the Macsquant® Analyzer 10 (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.). All experiments were conducted in duplicates. The flow cytometer was calibrated daily to assure proper instrument functioning. Consistent fluorescence measurements over time were monitored with URFP-30–2 beads (Spherotech Inc.).

P-Selectin expression

Platelet surface P-selectin expression was determined, using whole blood flow cytometry, by the modified method of Psaila et al., (2011) and Frelinger et al., (2015). The antibodies used were as follows: phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-P-selectin monoclonal antibody (CD62P, clone AK4, 2 μg/ml final, Biolegend Inc.) and peridinin-chlorophyll-protein (PerCP)-conjugated anti-GPIIIa (CD61) monoclonal antibody (clone VI-PL2, 2 μg/ml final, Biolegend Inc.). PE-conjugated mouse IgG1 isotype (Biolegend Inc.) served as a negative control for P-selectin. Aliquots of whole blood (5 μl) were incubated with 5 μl fluorescently-labeled monoclonal antibodies and 2.5 μl either ADP, TRAP or HEPES Tyrode’s buffer for 15 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by a 15-fold dilution with 1% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were maintained at room temperature and not agitated until fixation was completed to prevent handling activation. They were further diluted 35-fold with PBS and analyzed within 24 hours. For each sample 10,000 CD61 PerCP positive platelet events were acquired. Platelet surface P-selectin expression was measured relative to the negative control as percentage of CD62P PE positive platelets.

Platelet-neutrophil aggregates (PNA)

The method of Nagasawa et al., (2012) was modified for analysis of platelet-neutrophil aggregates. Whole blood sample (5 μl) was incubated with 5 μl antibodies and 2.5 μl of either ADP, TRAP or HEPES-Tyrode buffer for 10 min at room temperature (25 °C). The antibodies used were PE-conjugated anti-CD45 monoclonal antibody (clone HI30, Biolegend Inc., 8 μg/ml final, CD45 is a pan-leukocyte protein), PerCP-conjugated anti-CD61 monoclonal antibody (clone VI-PL2, Biolegend Inc., 2 μg/ml final) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-CD16 (FcγRIII receptor) monoclonal antibody (clone NKP15, Beckton Dickinson, 4 μg/ml final). Samples were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 25 °C, followed by red blood cell lysis by hypotonic shock. The volume was made up to 250 μl with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry. Fluorescence trigger was set on the B2 (PE) channel.

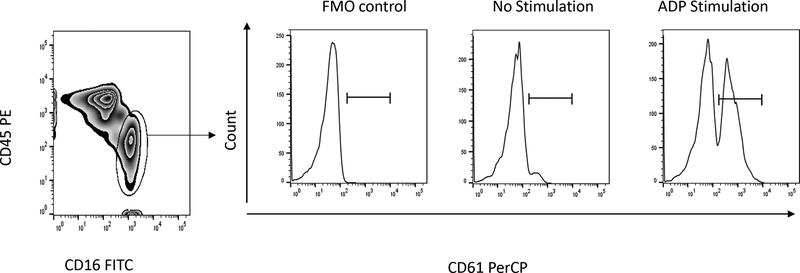

CD45LO and CD16+ double positive cells were gated as the neutrophil population after doublet discrimination. Fluorescence minus one (FMO) isotype controls, without PerCP-conjugated anti-CD61 monoclonal antibody, served as a negative control. PNA were identified as the percentages of CD61+ cells in the gated neutrophil populations, and defined by fluorescence intensity exceeding that of 99% of FMO control neutrophils (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Gating for platelet-neutrophil aggregates. In the scatter plot at left, neutrophils were gated as the CD45LO and CD16+ double positive cell population. Histograms at right show the percent of platelet-neutrophil aggregates positive for CD61 (right panels) without and with stimulation with ADP (right panel) or TRAP (data not shown). The left histogram shows the fluorescence minus one (FMO) control used to set gates for CD61 positivity.

Statistical analysis

The study population was grouped in three categories based on gestational age: preterm (< 34 weeks), late preterm (34 to < 37 weeks) and term (≥ 37 weeks). Data were analyzed for normality by the Kolmogorov Smirnoff test and by boxplots, and data that did not follow a normal distribution were transformed (logarithmically). Non-parametric data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test and reported as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were examined using the Chi-square test. Cord blood platelet markers and parametric study characteristics between preterm, late preterm and term neonatal groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between cord blood platelet-neutrophil aggregates and P-selectin. We set α level at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed with the IBM SPSS for windows statistical package version 22.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. Sixty-four neonates from 23 to 40 weeks gestation were enrolled in this study. They were stratified into 3 groups based on their gestational ages; preterm (n=21), late preterm (n=22) and term (n=21), with gestational ages of 30.9±2.9 weeks, 34.9±0.8 weeks and 39.1±1.1 weeks, respectively. Their birthweights were 1665±538g, 2351±624g and 3379±509g, respectively. Gender distribution between the groups were similar (p=.875), although more males (n=40) than females (n=24) (p=.046) were enrolled in the study. The groups did not differ significantly with respect to mode of delivery, age of the mother or Apgar scores at 1 or 5 minutes.

Table 1:

Subject Characteristics

| Preterm (21) | Late preterm (22) | Term (21) | P-Value | |

| Birthweight (g, Mean ± SD ) | 1665 ±538 | 2351 ±624 | 3379 ± 509 | <.001a |

| Gestation age (weeks, Mean ± SD) | 30.9 ±2.9 | 34.9 ±0.8 | 39.1 ±1.1 | <.001a |

| Maternal age (years, Mean ± SD ) | 29.3 ±7.5 | 27.5 ±5.7 | 30.9 ±7.2 | .270a |

| Female | 8(38) | 9 (40.9) | 7(33.3) | |

| Vaginal delivery | 8(38) | 13 (59.1) | 7(33.3) | |

| Apgar score (1 minute) median (IQR) | 7 (5–8) | 8 (7–8) | 8 (8–8) | .165c |

| Apgar score (5 minute) median (IQR) | 8 (8–9) | 8 (8–9) | 9 (9–9) | .053c |

One-way ANOVA

Pearson Chi-square test

Kruskal-Wallis test

IQR= interquartile range

Formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates

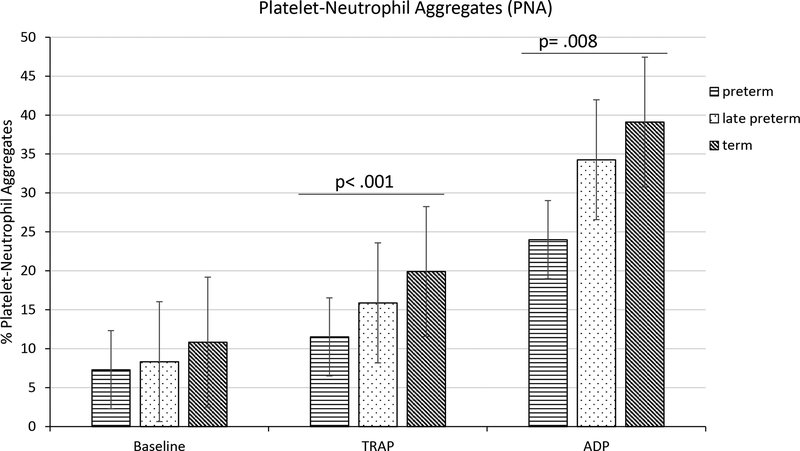

Significant differences were observed between groups in the percentage of neutrophils associated with platelets (PNA formed) in response to either TRAP or ADP mediated platelet activation. Bonferroni post hoc comparison revealed that percentage PNA formed in preterm newborns, after TRAP or ADP stimulations, were significantly lower than in term neonates (11.5 ± 5.2% vs 19.9 ± 9.1%, p < .001 or 24.0 ± 10.1% vs 39.1 ± 18.2%, p = .008, respectively) (Fig. 2). Neutrophils from cord blood of late preterm newborns were intermediate between preterm and term newborns (15.9 ± 5.0% or 34.3 ± 10.0% after TRAP or ADP mediated activation, respectively). No significant differences were observed between groups without platelet activation.

Figure 2.

Platelet-Neutrophil Aggregates. Percentage CD61 PerCP positive neutrophils in cord blood of preterm (n=21), late preterm (n=22) and term (n=21) newborns. Results are mean ± SD, analysis based on one-way ANOVA test and Bonferroni multiple comparison. Power for ANOVA analysis of PNA after TRAP and ADP stimulations were .90 and .76 respectively.

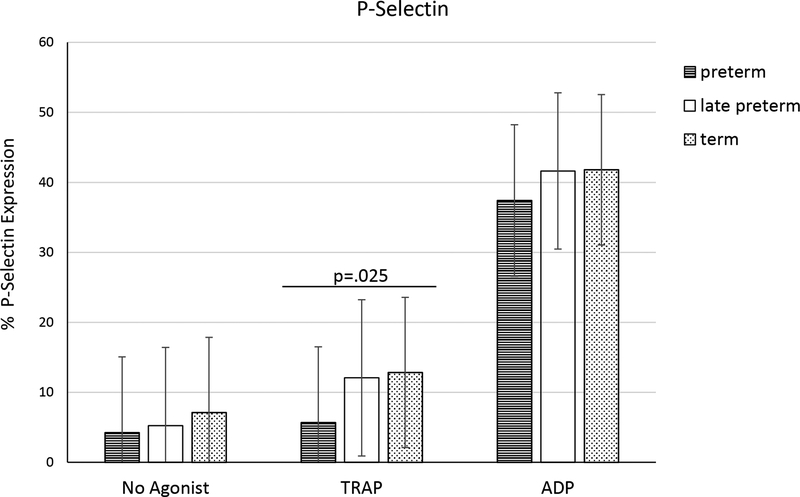

Expression of P-selectin

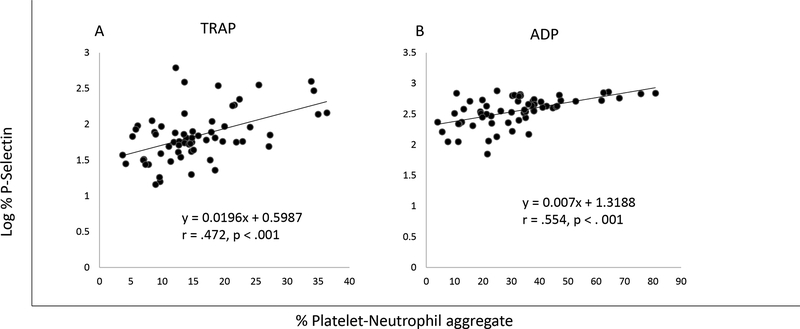

The percentage of platelets expressing P-selectin was analyzed for each of the groups. Log transformed platelet P-selectin expression was significantly lower in preterm (5.7 ± 3.7%) compared to late preterm (12.1 ± 15.1%) or term (12.9 ± 11.2%) neonates (p = .025) after stimulation with TRAP (Fig. 4). However, with current sample numbers the estimated power = 0.48. Nevertheless, log transformed percentages of P-selectin positive platelets correlated with neutrophil interactions (PNA), having Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = .472 (p < .001, power = 0.98) and .554 (p < .001, power = 0.99) following TRAP and ADP activations, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

The percentage cord blood platelets expressing P-Selectin in preterm (n=21), late preterm (n=22) and term (n=21) newborns. Results are mean ±SD, analysis based on one-way ANOVA after log transformation. Power = .48 for P-Selectin expression after TRAP stimulation.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation of the log % P-Selectin positive platelets with platelet-neutrophil aggregates in the cord blood samples of 64 neonates during (A) TRAP (power=.98) and (B) ADP (power=.99) stimulations.

DISCUSSION

Premature neonates are at increased risk for hemorrhagic and inflammatory morbidities such as periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding and sepsis. Platelets play an essential role as components of the hemostatic response to vascular breaches, limiting bleeding severity, particularly from the high pressure arterial vessels. The developmental aspects of the hemostatic system, and especially platelet activation and functions in the newborn, remain to be fully characterized. The objective of this study was to evaluate the formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates (PNA) and expression of platelet P-selectin in cord blood as a function of newborn’s gestational age at birth.

Platelet neutrophil interactions lead to physiological changes in platelets and neutrophils affecting their functions. Platelet aggregation and thromboxane release are enhanced by interactions with neutrophils, while neutrophils, in turn, utilize platelet derived phospholipids for chemokine production [29, 31]. In addition, this interaction promotes the recruitment of neutrophils to inflammatory tissues [32] and primes them for adhesion, phagocytosis and killing [33]. Lower neutrophil functions were reported in newborns as a whole [34] and in preterm neonates in particular [35]. Less frequent interactions between platelets and neutrophils presented here (Fig. 2) may contribute to lower neutrophil function in preterm newborns, and may partly explain the increased susceptibility to infections in this cohort [36]. Preterm newborns are known to be susceptible to infections in a way that is similar to that observed in adults with neutropenia [35]. Further studies are needed to explore the relevance of this interaction.

P-selectin is important for PNA formation and subsequent neutrophil function [37, 38]. We observed positive correlations between PNA levels and expression of P-selectin (Fig. 3), consistent with earlier work focusing on adult platelet leukocyte aggregates [39]. This is further supported by findings that platelet activation and P-selectin expression are needed for platelet-neutrophil complex formation [37].

P-selectin is one of the most analyzed platelet activation markers [40, 41]. It is released from platelet α-granules during activation and is important in the interaction of platelets with leukocytes or vascular endothelium [42, 43]. The expression of platelet P-selectin in newborns is lowest in the preterm group, consistent with earlier studies [44, 25]. However, these lower values only reached significance when TRAP was the agonist (Fig. 4). Moreover, we observed increased variability in P-selectin levels in our study population, similar to that reported by other investigators [44, 17, 23].

Platelet activation by TRAP resulted in marginal increases in P-selectin expression and PNA formation. This is consistent with other studies showing poor TRAP response of platelets at birth, due to low levels of the protease-activated receptors (PAR-1 and PAR-4) [45, 46]. Platelet responsiveness to TRAP was then observed to improve postnatally with age [24, 25, 46].

There is a clear correlation between PNA formation and P-selectin expression, regardless of the agonist used. Yet, it is of interest that correlation of PNA expression with gestational age is stronger than that of P-selectin expression. This implies that PNA formation is not solely dependent on platelets, but also requires functional developments of neutrophils, concordant with reported lower neutrophil functions in premature newborns [34].

Major findings of this study include: 1) significantly lower levels of platelet-neutrophil aggregates in preterm neonates, implying that the ability to form them increases with gestational age, 2) lower degranulation of platelet α-granules as measured by expressed P-selectin in preterm neonates in response to TRAP stimulation, and 3) significant positive correlations between P-selectin expression and PNA formation. Further studies are needed to examine the implication of these findings for newborn physiology and morbidity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dorothy Forde, Judy Gates and Salma Kabir for their invaluable help in obtaining informed consents for this study.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01 NR011209–08 and R25 GM060507.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Rights and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all patients for their inclusion in the study.

References

- 1.Brewer DB. Max Schultze (1865), G. Bizzozero (1882) and the discovery of the platelet. Br J Haematol. 2006;133(3):251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velden PV, Giles AR. A detailed morphological evaluation of the evolution of the haemostatic plug in normal, factor VII and factor VIII deficient dogs. Br J Haematol. 1988;70(3):345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1988.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vieira-de-Abreu A, Campbell RA, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets: versatile effector cells in hemostasis, inflammation, and the immune continuum. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(1):5–30. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Italiano JE, Richardson JL, Patel-Hett S, Battinelli E, Zaslavsky A, Short S et al. Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: pro-and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet α granules and differentially released. Blood. 2008;111(3):1227–1233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullinane AB, O’Callaghan P, McDermott K, Keohane C, Cleary PE. Effects of autologous platelet concentrate and serum on retinal wound healing in an animal model. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240(1):35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00417-001-0397-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Santanna J, Strom BL, Berlin JA. Effectiveness of Platelet Releasate for the Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):483–488. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youssefian T, Drouin A, Masse JM, Guichard J, Cramer EM. Host defense role of platelets: engulfment of HIV and Staphylococcus aureus occurs in a specific subcellular compartment and is enhanced by platelet activation. Blood. 2002;99(11):4021–4029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMorran BJ, Marshall VM, de Graaf C, Drysdale KE, Shabbar M, Smyth GK et al. Platelets kill intraerythrocytic malarial parasites and mediate survival to infection. Science. 2009;323(5915):797–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1166296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie M Beyond Clotting: The Powers of Platelets. Science. 2010;328(5978):562–564. doi: 10.1126/science.328.5978.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW et al. Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood. 2004;105(1):178–185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haley KM, Recht M, McCarty OJT. Neonatal platelets: mediators of primary hemostasis in the developing hemostatic system. Pediatr Res. 2014;76(3):230–237. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrew M, Castle V, Saigal S, Carter C, Kelton JG. Clinical Impact of Neonatal Thrombocytopenia. J Pediatr. 1987;110(3):457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmoneim AA, Zolaly M, El-Moneim EA, Sultan E. Prognostic significance of early platelet count decline in preterm newborns. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19(8):456–461. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.162462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baer VL, Lambert DK, Henry E, Christensen RD. Severe Thrombocytopenia in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):E1095–E1100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duppré P, Sauer H, Giannopoulou EZ, Gortner L, Nunold H, Wagenpfeil S et al. Cellular and humoral coagulation profiles and occurrence of IVH in VLBW and ELWB infants. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91(12):695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yulandari I, Rundjan L, Kadim M, Amalia P, Wulandari HF, Handryastuti S. The relationship between thrombocytopenia and intraventricular hemorrhage in neonates with gestational age< 35 weeks. Paediatr Indones. 2016;56(4):242–250. doi: 10.14238/pi56.4.2016.242-50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frelinger AL 3rd, Grace RF, Gerrits AJ, Berny-Lang MA, Brown T, Carmichael SL et al. Platelet function tests, independent of platelet count, are associated with bleeding severity in ITP. Blood. 2015;126(7):873–879. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-628461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatti L, Guarneri D, Caccamo M, Gianotti G, Marini A. Platelet activation in newborns detected by flow-cytometry. Neonatology. 1996;70(6):322–327. doi: 10.1159/000244383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grosshaupt B, Muntean W, Sedlmayr P. Hyporeactivity of neonatal platelets is not caused by preactivation during birth. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156(12):944–948. doi: 10.1007/s004310050748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajasekhar D, Barnard MR, Bednarek FJ, Michelson AD. Platelet hyporeactivity in very low birth weight neonates. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77(5):1002–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss T, Levy-Shraga Y, Ravid B, Schushan-Eisen I, Maayan-Metzger A, Kuint J et al. Clot formation of neonates tested by thromboelastography correlates with gestational age. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(2):344–350. doi: 10.1160/th09-05-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roschitz B, Sudi K, Köstenberger M, Muntean W. Shorter PFA-100® closure times in neonates than in adults: role of red cells, white cells, platelets and von Willebrand factor. Acta Pædiatr. 2001;90(6):664–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2001.tb02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cade JF, Hirsh J, Martin M. Placental barrier to coagulation factors: its relevance to the coagulation defect at birth and to haemorrhage in the newborn. Br Med J. 1969;2(5652):281–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5652.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietrucha T, Wojciechowski T, Greger J, Jedrzejewska E, Nowak S, Chrul S et al. Differentiated reactivity of whole blood neonatal platelets to various agonists. Platelets. 2001;12(2):99–107. doi: 10.1080/09537100020032281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitaru AG, Holzhauer S, Speer CP, Singer D, Obergfell A, Walter U et al. Neonatal platelets from cord blood and peripheral blood. Platelets. 2005;16(3–4):203–210.doi: 10.1080/09537100400016862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun OO, Slotta JE, Menger MD, Erlinge D, Thorlacius H. Primary and secondary capture of platelets onto inflamed femoral artery endothelium is dependent on P-selectin and PSGL-1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;592(1–3):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semple JW, Freedman J. Platelets and innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(4):499–511. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornerup KN, Salmon GP, Pitchford SC, Liu WL, Page CP. Circulating platelet-neutrophil complexes are important for subsequent neutrophil activation and migration. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(3):758–767. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01086.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faint RW. Platelet—neutrophil interactions: Their significance. Blood Rev. 1992;6(2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/0268-960X(92)90010-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam FW, Burns AR, Smith CW, Rumbaut RE. Platelets enhance neutrophil transendothelial migration via P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300(2):H468–H475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00491.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faraday N, Scharpf Robert B, Dodd-o Jeffrey M, Martinez Elizabeth A, Rosenfeld Brian A, Dorman T. Leukocytes Can Enhance Platelet-mediated Aggregation and Thromboxane Release via Interaction of P-selectin Glycoprotein Ligand 1 with P-selectin. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(1):145–151. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200101000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarbock A, Polanowska-Grabowska RK, Ley K. Platelet-neutrophil-interactions: linking hemostasis and inflammation. Blood Rev. 2007;21(2):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters MJ, Dixon G, Kotowicz KT, Hatch DJ, Heyderman RS, Klein NJ. Circulating platelet-neutrophil complexes represent a subpopulation of activated neutrophils primed for adhesion, phagocytosis and intracellular killing. Br J Haematol. 1999;106(2):391–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipp P, Ruhnau J, Lange A, Vogelgesang A, Dressel A, Heckmann M. Less Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation in Term Newborns than in Adults. Neonatology. 2017;111(2):182–188. doi: 10.1159/000452615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carr R Neutrophil production and function in newborn infants. Br J Haematol. 2000;110(1):18–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simonsen KA, Anderson-Berry AL, Delair SF, Davies HD. Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(1):21–47. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00031-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mauler M, Seyfert J, Haenel D, Seeba H, Guenther J, Stallmann D et al. Platelet-neutrophil complex formation—a detailed in vitro analysis of murine and human blood samples. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;99(5):781–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3TA0315-082R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuchtriegel G, Uhl B, Puhr-Westerheide D, Pörnbacher M, Lauber K, Krombach F et al. Platelets Guide Leukocytes to Their Sites of Extravasation. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(5):e1002459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irving PM, Macey MG, Shah U, Webb L, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(4):361–372. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martínez-Sánchez SM, Minguela A, Prieto-Merino D, Zafrilla-Rentero MP, Abellán-Alemán J, Montoro-García S. The Effect of Regular Intake of Dry-Cured Ham Rich in Bioactive Peptides on Inflammation, Platelet and Monocyte Activation Markers in Humans. Nutrients. 2017;9(4):321. doi: 10.3390/nu9040321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morel A, Rywaniak J, Bijak M, Miller E, Niwald M, Saluk J. Flow cytometric analysis reveals the high levels of platelet activation parameters in circulation of multiple sclerosis patients. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;43(1–2):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-2955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dole VS, Bergmeier W, Mitchell HA, Eichenberger SC, Wagner DD. Activated platelets induce Weibel-Palade-body secretion and leukocyte rolling in vivo: role of P-selectin. Blood. 2005;106(7):2334–2339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandendries ER, Furie BC, Furie B. Role of P-selectin and PSGL-I in coagulation and thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92(3):459–466. doi: 10.1160/TH04-05-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wasiluk A, Mantur M, Szczepanski M, Kemona H, Baran E, Kemona-Chetnik I. The effect of gestational age on platelet surface expression of CD62P in preterm newborns. Platelets. 2008;19(3):236–238. doi: 10.1080/09537100701882046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlagenhauf A, Schweintzger S, Birner-Grünberger R, Leschnik B, Muntean W. Comparative evaluation of PAR1, GPIb-IX-V, and integrin αIIbβ3 levels in cord and adult platelets. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30(4A, Suppl.1):S164–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlagenhauf A, Schweintzger S, Birner-Gruenberger R, Leschnik B, Muntean W. Newborn platelets: Lower levels of protease-activated receptors cause hypoaggregability to thrombin. Platelets. 2010;21(8):641–647. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2010.504869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]