Abstract

Background

Residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods report higher levels of depressive symptoms; however, few studies have employed prospective designs during adolescence, when depression tends to emerge. We examined associations of neighborhood social fragmentation, income inequality, and median household income with depressive symptoms in a nationally representative survey of adolescents.

Methods

The NEXT Generation Health Study enrolled 10th-grade students from 81 United States high schools in the 2009–2010 school year. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Modified Depression Scale (Wave 1) and the pediatric Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (Waves 2–6). Neighborhood characteristics at Waves 1, 3, 4, 5 were measured at the census tract level using geolinked data from the American Community Survey 5-year estimates. We used linear mixed models to relate neighborhood disadvantage to depressive symptoms controlling for neighborhood and individual sociodemographic factors.

Results

None of the models demonstrated evidence for associations of social fragmentation, income inequality, or median household income with depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Despite the prospective design, repeated measures, and nationally representative sample, we detected no association between neighborhood disadvantage and depressive symptoms. This association may not exist or may be too small to detect in a geographically dispersed sample. Given the public health significance of neighborhood effects, future research should examine the developmental timing of neighborhood effects across a wider range of ages than in the current sample, consider both objective and subjective measures of neighborhood conditions, and use spatially informative techniques that account for conditions of nearby neighborhoods.

INTRODUCTION

The neighborhood environment appears to be an important determinant of mental health [1]. Neighborhood attributes linked to depression include socioeconomic disadvantage, instability, lack of social cohesion, and income inequality [2–4]. Social theories (e.g., social ecologic, social cognitive, social stress) [5] suggest that associations of neighborhood attributes with depression arise from lack of investment and limited resources for health-promoting behaviors in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Resource constraints break down social processes at the aggregate (e.g., through low social cohesion) and individual (e.g., through breaking social ties [6–10]) levels that benefit mental well-being [5]. Associations of low neighborhood income with depression may arise because of increased exposure to interpersonal violence and other stressful life events in contexts without sufficient social and material supports to buffer their effects [11], and high income inequality generates invidious social comparisons which are deleterious for mental health [12]. Associations of neighborhood income or income inequality with depression may also exist because of higher social fragmentation or lower social cohesion in more disadvantaged, less egalitarian places [13, 14].

Neighborhood economic disadvantage is captured by median household income and percentages of residents below the poverty line, with less than high school education, unemployed, and receiving public assistance. We found 26 studies showing that residents of neighborhoods with higher economic disadvantage had higher scores on depressive symptom scales and higher risks of major depressive disorder (e.g., odds ratios 1.05 to 2.40) [3, 4]. Residents of neighborhoods with higher income inequality also had higher levels of depressive symptoms [12, 15, 16] However, there were 19 studies in which neighborhood disadvantage was not associated with depression.

In 12 studies, residents of socially disadvantaged neighborhoods (i.e., characterized by residential instability or low social cohesion) had higher mean levels of depressive symptoms and higher risks for clinical depression; conversely, residents of neighborhoods with lower social disadvantage (e.g., greater social cohesion) had lower scores and lower risks. In other studies, however, neighborhood social disadvantage was not associated with residents’ depression.

These inconsistent findings may reflect methodologic differences between studies such as prospective versus cross-sectional study designs, focus on single regions or population subgroups rather than nationally representative samples, sample size, length of follow-up, definition of neighborhood (census tract or ZIP code versus respondent-defined neighborhood boundaries), assessment of disadvantage (Census data vs. respondents’ perceptions), and measurement of depression. Prospective studies with longer follow-up periods were less likely to detect associations of neighborhood social or economic disadvantage with depression. The studies reporting associations were based on follow-up periods <5 years [3, 4, 17]. Of the studies reporting no associations between neighborhood context and depression, 9 had follow-up periods ≥ 5, and 5 followed up respondents for ≥ 10, years [3, 4, 17–20]. Notably, few studies with follow-up periods >5 years included repeated measures of neighborhood exposures, which could fail to detect associations if neighborhood effects decay over time.

Neighborhood studies of mental health, most of which focused on adults or young children [3, 4, 17], may also have missed the developmental period of greatest risk, as depression tends to emerge during adolescence [21, 22]. Pabayo et al. reported an association between higher income inequality and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls but not boys [12]. In contrast, Airaksinen et al. found that neighborhood socioeconomic conditions were not associated with depressive symptoms measured repeatedly over 5 waves in young adulthood, though neighborhood conditions were only assessed at baseline [18]. Similarly, in a 14-year study of depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents, Barr found that Census-based neighborhood socioeconomic conditions at baseline were unrelated to depression, whereas participants’ perceptions of neighborhood safety and neglect were associated with higher depressive symptoms [19]. However, the use of subjective measures is problematic if individuals with depression perceive their neighborhoods more negatively than individuals without depression [23, 24].

Because of these inconsistent findings, we examined prospective associations of 3 features of neighborhood conditions with depressive symptoms in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: social fragmentation, neighborhood income inequality, and median household income. We leveraged the following design strengths of the NEXT Generation Health Study (“NEXT”; [25]): 1) a nationally representative sample; 2) 6 annual follow-up assessments providing repeated measures of depressive symptoms through young adulthood; and 3) repeated measurement of neighborhood exposures utilizing objective, Census-derived neighborhood characteristics geolinked to respondents’ addresses at 4 study waves. We hypothesized that higher social fragmentation, lower median household income, and higher income inequality would be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms between ages 16 and 22.

METHODS

Sample

NEXT enrolled a nationally representative sample of adolescents using a 3-stage stratified design targeting 10th graders enrolled in public, private or parochial high schools in the United States in school year 2009–2010 [25]. Primary sampling units (PSUs, n=27) consisted of school districts or groups of school districts stratified by U.S. Census divisions. Schools in each PSU with 10th-grade classes were sampled with probability proportional to enrollment; 58.4% of sampled schools (n=81) participated. All students within randomly selected classrooms (1 to 5 per school) were eligible to participate. Parents provided informed consent for their children’s participation and youth provided assent (if <18 years of age) and consent once they reached 18 years of age. The protocol including informed consent procedures was approved by the institutional review board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and conforms to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Among eligible students, 73.4% (n=2,786) participated. Baseline surveys were administered in 2009–2010; however, timing of school approval for participation resulted in the collection of baseline data for 260 respondents during Wave 2 (2010–2011, 11th grade). This study used data from the first 6 annual waves that were self-administered either in school or online. Retention rates were 86.8% at Wave 2, 83.9% at Wave 3, 75.9% at Wave 4, 76.6% at Wave 5, and 79.9% at Wave 6. Schools with large percentages of African American students were oversampled to obtain reliable estimates for them.

Measures

Depressive symptoms.

We assessed depressive symptoms at Wave 1 using the Modified Depression Scale (MDS) [26]. The MDS asks respondents to rate, on a Likert scale from “never” to “always,” the frequency with which they experienced symptoms such as sadness, grouchiness or irritability, and increases or decreases in appetite and sleep over the past 30 days (Cronbach’s α=0.76 to 0.80) [26–28].

At Waves 2–6, we measured depressive symptoms using the pediatric Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS [29]) scale. This scale asks respondents to rate, on a Likert scale from “never” to “almost always” [30], the frequency with which they experienced symptoms including feeling that they can’t do anything right, feeling that everything in their lives had gone wrong, and being unable to stop feeling sad over the preceding 7 days (Cronbach’s α=0.85 and test-retest reliability=0.76) [31]. The decision to switch from the MDS to the PROMIS reflected accumulating evidence of its desirable psychometric properties such as internal consistency and test-retest reliability and discrimination over wider ranges of depressive severity [30–34].

Scores on the PROMIS were converted into T-scores based on distributions of scores in the general U.S. pediatric population. We analyzed depressive symptom T-scores for the PROMIS (mean=50, standard deviation=10) and MDS scores standardized to the same mean and standard deviation. The correlation between MDS at Wave 1 and PROMIS at Wave 2 was 0.48, very similar to correlations between PROMIS scores at any 2 consecutive waves (0.50 to 0.54), suggesting the two measures are performing similarly in the NEXT sample and justifying our combining them for analysis.

Neighborhood characteristics.

Respondents’ home addresses were geocoded to census tracts at Waves 1, 3, 4, and 5. Consistent with previous studies of neighborhood disadvantage and adverse health outcomes [35–39], and because of their greater stability compared with single-year estimates, neighborhood measures were based on 5-year census tract-level estimates from the American Community Survey (ACS [40]): 2007–2011 for Wave 1, 2009–2013 for Wave 3, 2010–2014 for Wave 4, and 2011–2015 for Wave 5. Neighborhood characteristics were therefore updated based on respondents’ geocoded census tracts at Waves 3, 4, and 5. Because respondents were not geocoded at Waves 2 and 6, we applied the values of the neighborhood variables at Wave 1 to Wave 2 and those at Wave 5 to Wave 6. All neighborhood variables were standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 in the total U.S. population and treated as time varying in all models. At baseline there were 1,105 census tracts represented in the sample; census tracts were more geographically dispersed than PSU’s, with an average of 41 census tracts represented within each PSU.

Social Fragmentation is an index consisting of the sum of the standardized percentages in respondents’ census tracts of female-headed households, residents living in the area <5 years, foreign born residents, and renters [41]. Single-parent households are significantly more likely than 2-parent households to be poor [42]. Poverty, particularly among single mothers, is a strong risk factor for lack of social support that might buffer the stress resulting from competing demands of supporting their families financially, parenting, and other life tasks [43–45]. This constellation of adversity may contribute to role overload [46]. Higher proportions of households in these circumstances may mean fewer adults able to act as long-term, stable, dependable sources of emotional and adaptive social support or consistently enforced norms of prosocial behavior [6, 47]. Cultural and linguistic barriers in neighborhoods with high proportions of immigrants [47, 48], and the residential instability and turnover that frequently characterize renters, may likewise make it difficult to develop and maintain such ties [17, 47, 48].

We assessed income inequality using the Gini Index [49]. A value of 0 denotes perfect income equality, whereas a value of 1 denotes the scenario of all income accruing to 1 individual. Median household income in the ACS was adjusted for inflation to the final year covered by each relevant 5-year estimate (e.g., 2014 for Wave 4) using the Consumer Price Index [50]. To enable the assessment of potentially nonlinear associations between neighborhood variables and depressive symptoms, we categorized the neighborhood variables into quartiles of their distributions in the study sample for analysis.

Time-varying covariates adjusted for in the analyses were minority composition of the neighborhood (proportion non-White) and respondent age. Respondent-level covariates ascertained at baseline were sex, race/ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino, Black/African-American, White, other), and family socioeconomic status measured using Health Behaviour School-Aged Family Affluence Scale [51]. This scale is the summed score of 4 items querying family car (0, 1, 2+) and computer (0, 1, 2+) ownership, past-year frequency of family vacations (0, 1, 2+), and whether respondents had their own bedrooms (0=no, 1=yes). Scores ranged from 0 to 7 and were categorized as low (0–4), moderate (5–6), or high (7).

Analytic Approach

Respondents successfully geocoded to census tracts who provided data on sex, family affluence, race/ethnicity, age, and at least 1 measurement of depressive symptoms between Waves 1–6 of the study were included in the analysis sample (n=2,752). Among survey respondents at each wave, 18 of 2524 were missing geocodes at Wave 1, 3 of 2395 at Wave 3, 30 of 2177 at Wave 4, and 6 of 2202 at Wave 5.

We fit linear mixed models with random intercepts for PSUs and individual respondents nested within PSUs to account for the non-independence of respondents sampled from the same PSU and within-person correlation over time. The first set of models examined associations of each covariate with depressive symptoms adjusted only for respondent age. Next, we fit separate multivariable models examining each neighborhood exposure adjusted for respondent-level covariates (Model 1). As associations of neighborhood income and income inequality may be due in part to differences in social fragmentation across neighborhoods, we fit models with income only, income inequality only (Model 2) and both (Model 3), followed by a model that added social fragmentation (Model 4), each adjusted for respondent- and neighborhood-level covariates. All analyses incorporated NEXT’s sampling weights and were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean age of respondents at enrollment was 16.3 years. Forty-six percent of the sample was male; 55.7% self-identified as non-Hispanic White, 20.2% as non-Hispanic Black or African-American, 19.3% as Hispanic, and 4.8% as another race or ethnicity. Almost half (48.6%) reported moderate family affluence. Over the 6 survey waves, there were minimal changes in respondent depressive symptoms, family affluence, race/ethnicity, and neighborhood income inequality, percentage of minority residents, and median household income (Table 1). However, the percentages of male respondents decreased and residents of more socially fragmented neighborhood increased over time.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of NEXT Respondents (Total N = 2752) and Their Residential Neighborhoods by Survey Wave, % or Mean (Standard Error)a

| Characteristic | Wave 1 (n= 2486) | Wave 2 (n=2388) | Wave 3 (n=2354) | Wave 4 (n=2088) | Wave 5 (n=2118) | Wave 6 (n=2042) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptom T-score | 50.7 (0.4) | 51.2 (0.5) | 50.5 (0.6) | 50.4 (0.4) | 51.2 (0.4) | 50.9 (0.4) |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||||

| Social Fragmentation Indexb | ||||||

| Lowest quartile | 33.2 (4.9) | 32.2 (5.3) | 32.6 (5.6) | 35.9 (3.7) | 36.3 (4.2) | 33.9 (4.6) |

| Second quartile | 43.8 (6.3) | 43.4 (6.2) | 40.4 (6.1) | 29.2 (3.2) | 32.2 (3.6) | 32.3 (3.8) |

| Third quartile | 14.3 (4.2) | 15.6 (4.5) | 17.2 (4.5) | 18.4 (3.0) | 18.4 (2.7) | 19.9 (3.0) |

| Highest quartile | 8.8 (3.7) | 8.9 (3.6) | 9.9 (3.7) | 16.5 (2.4) | 13.0 (2.8) | 13.8 (3.0) |

| Gini coefficient of income inequalityb | ||||||

| Lowest quartile | 29.5 (5.7) | 29.6 (5.8) | 27.8 (5.3) | 28.3 (3.8) | 29.4 (3.4) | 28.8 (3.5) |

| Second quartile | 25.0 (2.5) | 24.2 (2.4) | 25.4 (2.9) | 24.7 (2.7) | 26.8 (2.9) | 25.6 (3.0) |

| Third quartile | 25.6 (4.3) | 24.8 (4.1) | 23.9 (3.5) | 24.9 (3.8) | 26.1 (3.0) | 26.5 (3.1) |

| Highest quartile | 19.9 (5.3) | 21.4 (5.6) | 23.0 (5.4) | 22.2 (2.0) | 17.7 (2.9) | 19.1 (3.1) |

| Neighborhood median household incomeb | ||||||

| Lowest quartile | 20.1 (5.6) | 21.3 (5.8) | 20.7 (5.2) | 23.3 (2.8) | 20.7 (2.4) | 22.4 (3.0) |

| Second quartile | 18.0 (3.6) | 17.6 (3.4) | 20.2 (3.2) | 20.9 (2.5) | 21.0 (2.6) | 22.3 (3.0) |

| Third quartile | 30.1 (4.9) | 29.5 (4.8) | 28.6 (4.6) | 30.2 (3.1) | 29.1 (3.2) | 26.4 (3.3) |

| Highest quartile | 31.8 (5.5) | 31.6 (5.7) | 30.5 (5.5) | 25.6 (3.6) | 29.2 (4.3) | 28.9 (4.3) |

| Percentage of minority residentsb | ||||||

| Lowest quartile | 33.0 (5.5) | 32.8 (5.8) | 31.6 (5.7) | 36.1 (4.6) | 34.0 (4.7) | 32.1 (5.0) |

| Second quartile | 44.9 (6.9) | 43.4 (6.8) | 43.7 (6.8) | 38.8 (4.9) | 42.4 (5.7) | 40.3 (6.0) |

| Third quartile | 13.5 (3.6) | 12.7 (3.5) | 13.6 (3.6) | 14.3 (3.3) | 14.2 (3.2) | 15.3 (3.3) |

| Highest quartile | 8.6 (4.5) | 11.1 (5.2) | 11.1 (5.2) | 10.9 (3.2) | 9.4 (3.2) | 12.3 (4.2) |

| Respondent/Family-Level Characteristics | ||||||

| Sex (% male) | 45.6 (1.7) | 44.8 (1.8) | 44.8 (1.6) | 41.2 (2.0) | 40.1 (1.9) | 38.4 (1.9) |

| Age | 16.3 (0.03) | 17.2 (0.03) | 18.2 (0.03) | 19.2 (0.02) | 20.3 (0.02) | 21.3 (0.02) |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 57.8 (5.4) | 58.8 (6.0) | 58.8 (6.0) | 62.1 (5.8) | 61.1 (5.3) | 57.1 (6.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African-American | 17.6 (3.6) | 17.3 (4.1) | 17.1 (4.1) | 13.5 (3.3) | 13.6 (3.4) | 19.7 (4.9) |

| Hispanic | 19.7 (3.9) | 19.5 (4.0) | 19.9 (3.9) | 19.5 (4.3) | 19.9 (3.8) | 18.7 (3.8) |

| Other | 5.0 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.9 (1.0) | 5.4 (1.0) | 4.5 (1.1) |

| Family affluence | ||||||

| Low | 23.9 (2.7) | 23.0 (2.9) | 23.0 (3.1) | 22.2 (2.7) | 22.5 (2.6) | 22.4 (3.1) |

| Medium | 48.8 (1.5) | 49.8 (1.2) | 49.0 (1.5) | 48.3 (1.8) | 49.2 (1.5) | 49.5 (1.6) |

| High | 27.3 (2.5) | 27.2 (2.5) | 28.0 (2.8) | 29.4 (2.7) | 28.4 (2.6) | 28.1 (2.7) |

Wave-specific percentages for some variables do not add to 100% because of rounding.

Neighborhood measures at each wave were standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 in all U.S. census tracts.

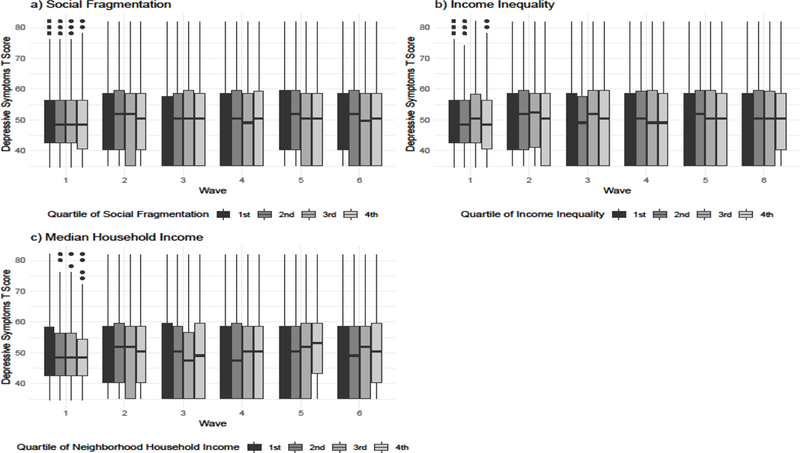

Distributions of depressive symptom T-scores by quartiles of neighborhood exposures within each wave are shown in Figure 1. The distribution of depressive symptoms was virtually the same across quartiles of the neighborhood social fragmentation, median income, and income inequality.

Figure 1. Depressive Symptom Scores at Waves 1–6 across Quartiles of Neighborhood Characteristics, NEXT Generation Health Study.

Boxplots of depressive symptoms are shown across waves 1–6 of the study for each quartile of neighborhood social fragmentation (panel a), income inequality (panel b), and median household income (panel c).

Results of linear mixed models of depressive symptoms are shown in Table 2. None of the models demonstrated evidence for associations of social fragmentation, income inequality, or median household income with depressive symptoms. For example, in the final regression model, there was no difference in mean depressive symptoms between residents of neighborhoods at the highest versus lowest quartiles of disadvantage: 0.06 for social fragmentation (95% confidence interval [18]: −0.95, 1.07); −0.43 for income inequality (95% CI: −1.14, 0.29); and −0.27 for median income (95% CI: −1.19, 0.64).

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients (95% Confidence Intervals) from Linear Mixed Models of Depressive Symptoms in the NEXT Generation Health Study, Waves 1–6 (n=2,752).

| Characteristic | Age-adjustedc | Model 1d | Model 2e | Model 3f | Model 4g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood | |||||

| Gini coefficient of income inequalitya,b | |||||

| Lowest quartile | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Second quartile | 0.17 (−0.35, 0.69) | 0.10 (−0.43, 0.64) | 0.10 (−0.45, 0.64) | 0.10 (−0.45, 0.66) | 0.15 (−0.43, 0.73) |

| Third quartile | −0.23 (−0.79, 0.33) | −0.33 (−0.90, 0.23) | −0.41 (−1.00, 0.17) | −0.38 (−0.98, 0.21) | −0.34 (−0.96, 0.28) |

| Highest quartile | −0.34 (−0.93, 0.24) | −0.43 (−1.02, 0.16) | −0.56 (−1.18, 0.05) | −0.46 (−1.14, 0.22) | −0.43 (−1.14, 0.29) |

| F, df=3 (P) | 1.3 (0.26) | 1.7 (0.18) | 2.4 (0.07) | 1.6 (0.18) | 1.6 (0.18) |

| Median household incomea,b | |||||

| Lowest quartile | −0.31 (−0.92, 0.30) | −0.46 (−1.09, 0.17) | −0.54 (−1.20, 0.11) | −0.30 (−1.01, 0.42) | −0.27 (−1.19, 0.64) |

| Second quartile | 0.10 (−0.51, 0.72) | 0.03 (−0.60, 0.65) | −0.06 (−0.68, 0.57) | 0.03 (−0.63, 0.69) | 0.06 (−0.68, 0.80) |

| Third quartile | −0.26 (−0.81, 0.30) | −0.28 (−0.86, 0.31) | −0.36 (−0.92, 0.20) | −0.29 (−0.87, 0.28) | −0.27 (−0.88, 0.34) |

| Highest quartile | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| F, df=3 (P) | 1.0 (0.39) | 1.3 (0.27) | 1.5 (0.22) | 0.8 (0.50) | 0.7 (0.53) |

| Social Fragmentation Indexa,b | |||||

| Lowest quartile | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||

| Second quartile | 0.22 (−0.28, 0.72) | 0.12 (−0.40, 0.64) | 0.06 (−0.54, 0.66) | ||

| Third quartile | −0.32 (−0.95, 0.31) | −0.49 (−1.16, 0.18) | −0.56 (−1.39, 0.27) | ||

| Highest quartile | 0.17 (−0.52, 0.87) | 0.03 (−0.75, 0.82) | 0.06 (−0.95, 1.07) | ||

| F, df=3 (P) | 1.3 (0.27) | 1.6 (0.20) | 1.7 (0.17) | ||

| Percentage of race/ethnic minority residentsa,b | |||||

| Lowest quartile | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | |

| Second quartile | 0.54 (0.02, 1.06) | 0.45 (−0.07, 0.97) | 0.61 (0.07, 1.16) | 0.66 (0.09, 1.23) | |

| Third quartile | 0.66 (−0.06, 1.37) | 0.48 (−0.31, 1.26) | 0.71 (−0.08, 1.50) | 0.88 (0.01, 1.74) | |

| Highest quartile | 0.19 (−0.63, 1.01) | −0.07 (−1.00, 0.86) | 0.14 (−0.79, 1.07) | 0.32 (−0.66, 1.31) | |

| F, df=3 (P) | 2.0 (0.12) | 1.7 (0.16) | 2.6 (0.05) | 2.5 (0.06) | |

| Respondent/Family | |||||

| Age, per yearb | −0.08 (−0.17, 0.00) | −0.08 (−0.16, 0.01) | |||

| Male Sex | −4.95 (−5.62, −4.29) | −4.94 (−5.61, −4.27) | −4.95 (−5.62, −4.28) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 0.83 (−0.13, 1.80) | 0.38 (−0.68, 1.43) | 0.41 (−0.73, 1.55) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0.18 (−0.72, 1.09) | 0.17 (−0.84, 1.18) | 0.19 (−0.87, 1.25) | ||

| Other | 2.58 (0.97, 4.19) | 2.22 (0.61, 3.84) | 2.22 (0.58, 3.86) | ||

| F, df=3 (P) | 3.9 (0.01) | 2.6 (0.05) | 2.5 (0.06) | ||

| Family Affluence | |||||

| Low | 0.51 (−0.44, 1.45) | 0.60 (−0.33, 1.53) | 0.59 (−0.35, 1.54) | ||

| Medium | −0.09 (−0.95, 0.77) | 0.13 (−0.72, 0.98) | 0.13 (−0.71, 0.98) | ||

| High | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||

| F, df=2 (P) | 1.1 (0.35) | 1.0 (0.38) | 0.9 (0.40) |

Age and neighborhood characteristics are modeled as time varying.

Neighborhood measures at each wave were standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 in all U.S. census tracts.

Each variable is modeled separately, adjusted only for respondent age.

Each neighborhood characteristic is analyzed in a separate regression adjusted for respondent- and family-level covariates.

Income inequality and median household income are modeled separately, each adjusted for respondent-/family- and neighborhood-level covariates.

Income inequality and median household income are modeled simultaneously, adjusted for respondent-/family- and neighborhood-level covariates.

All neighborhood, respondent- and family-level characteristics are entered simultaneously into a single model.

DISCUSSION

We used repeated annual measures from a prospective study of 2,752 respondents enrolled in 10th grade to examine associations of Census-based indicators of neighborhood social and economic disadvantage with depressive symptoms from mid-adolescence into emerging adulthood. We found no evidence of associations of social fragmentation, income inequality, or median household income of respondents’ neighborhoods and their levels of depressive symptoms.

Our study incorporated design strengths long advocated by neighborhood researchers: prospective follow-up, population-based sample not limited to a single geographic area, and objective, repeated assessments of neighborhood characteristics. Moreover, our study was conducted during a developmentally sensitive period for depression and used reliable measures of depressive symptoms. Given these strengths, our findings cast doubt on the existence of robust relationships between neighborhood social and economic disadvantage and depression among adolescents and emerging adults. These findings are compatible with those reported by many but not all studies with follow-up periods longer than 5 years [3, 4, 17, 52], and specifically with those reported by Airaksinen et al. [18] and Barr [19] that followed young people into adulthood. Although adolescence and emerging adulthood are important developmental phases for depression, our results, together with those of previous studies [3, 4, 17, 52], suggest that neighborhood structural characteristics may be more important during other phases. Alternatively, adolescents’ individual, family, or contextual factors during the period captured by the study that operated more proximally to the young people than their residential neighborhoods, which we were unable to measure, may have obscured any influences of their neighborhoods. Additionally, although neighborhood effects may decay over time, there may also be lagged effects over longer intervals than our study could capture.

Barr [19] found that associations between neighborhood disadvantage and depressive symptoms disappeared after respondent, parent, and interviewer perceptions of neighborhood safety and physical neglect were accounted for. If individuals do not perceive their neighborhoods as disadvantaged, neighborhoods with objectively disadvantageous structural characteristics may not be associated with a higher risk for depression. Adolescents and young adults may be less likely to perceive their neighborhoods as disadvantaged than older individuals, even in the presence of objective indicators, if their peers in similar neighborhoods also do not perceive their neighborhoods as disadvantaged [53]. Alternatively, supportive relationships with peers may buffer the stressors associated with neighborhood adversity that are implicated in the etiology of depression [53].

Potential study weaknesses include the use of 2 different measures of depressive symptoms with 2 different reporting periods and 2 different underlying metrics over the course of the study. However, results did not change when we reanalyzed the data using only the outcomes measured by the PROMIS. Short scales of depressive symptoms may not be sufficiently sensitive for detecting small to moderate neighborhood effects. The lack of neighborhood data from Waves 2 and 6 is also a potential concern; our inability to update neighborhood data at these waves could have attenuated associations with depressive symptoms if respondents moved to neighborhoods with qualitatively different social and economic conditions. Although residential census tracts are standard units of analyses in studies of neighborhood exposures, individuals’ daily lives may span multiple census tracts beyond their residences. There may also be substantial sociodemographic segregation within tracts that our measures did not capture.

Given the design strengths of our study – nationally representative and diverse sample, repeated assessments of both neighborhood characteristics and depressive symptoms, and reliable measures of depression – it is tempting to interpret our results as suggesting that, at least on a national level and among adolescents and emerging adults, neighborhood social and economic characteristics are not associated with mental health. Nevertheless, the potential weaknesses noted above and generally discounted in the aggregate may have obscured real but small effects. The public health implications of putative neighborhood effects are important because they can have diffuse impacts over large numbers of individuals and because of the substantial burden attributable to depression [54]. Therefore, we offer the following suggestions for strengthening future studies.

Future attempts to resolve inconsistent findings concerning the role of neighborhood disadvantage in the risk of depression across the life course will benefit from incorporating prospective designs spanning multiple developmental phases, particularly the highest-risk periods of adolescence and early adulthood [21, 22]. Future studies might also consider both objective and subjective neighborhood measures and accessibility of services and amenities such as green space that might mitigate deleterious effects of neighborhood disadvantage [55]. Multiple statistical approaches could be utilized, including spatial analyses that take conditions of nearby neighborhoods into account and provide finer-grained characterization of respondents’ neighborhoods. Clarifying the potential mental health risks associated with neighborhood disadvantage, including their developmental phase specificity, and identifying neighborhood-level targets for intervention, will ultimately benefit efforts toward optimizing the mental health of adolescents and emerging adults.

What is already known on this subject.

Neighborhood social and economic disadvantage, social fragmentation, and income inequality have been associated with depression in some but not all studies.

Few prospective follow-up studies of neighborhood effects on depression have been conducted during adolescence, when depression tends to emerge, few have utilized nationally representative samples, and few have obtained repeated measures of neighborhood characteristics.

What this study adds.

We detected no associations of neighborhood disadvantage with depressive symptoms from mid-adolescence into emerging adulthood despite a prospective design, nationally representative United States sample, and repeated measures of both neighborhood disadvantage and depressive symptoms.

Neighborhood effects on depression may be too small to detect in geographically dispersed samples of adolescents and young adults.

Future research should consider the developmental timing of neighborhood effects, assess both objective and subjective neighborhood measures, and utilize multiple analytic approaches, including spatial techniques that account for conditions of nearby neighborhoods and provide more refined characterization of individual respondents’ neighborhood exposures.

Acknowledgments

This research (contract number HHSN275201200001I) was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We are grateful for the expert data management and statistical programming support of Ms. Gina Ma.

Data Sharing: Data from the Next Generation Health Study are available through the Data and Specimen Sharing Hub (DASH), a centralized data resource for researchers to access data from research studies funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for use in secondary research. For further information, please visit: https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/.

Footnotes

A preliminary version of parts of this paper was presented as a poster at the 51st Annual Meeting of the Society for Epidemiologic Research, Baltimore, MD, June, 2018.

Competing Interest

None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The views, opinions, and assertions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views or the official policy or position of any of the sponsoring organizations or agencies or the US government, including the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:125–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miles R, Coutts C, Mohamadi A. Neighborhood urban form, social environment, and depression. J Urban Health 2012;89:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson R, Westley T, Gariepy G, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1641–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:940–6, 8 p following 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paczkowski MM, Galea S. Sociodemographic characteristics of the neighborhood and depressive symptoms. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2010;23:337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagg J, Curtis S, Stansfeld SA, et al. Area social fragmentation, social support for individuals and psychosocial health in young adults: evidence from a national survey in England. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:242–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flouri E, Midouhas E, Joshi H, et al. Neighbourhood social fragmentation and the mental health of children in poverty. Health Place 2015;31:138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivory VC, Collings SC, Blakely T, et al. When does neighbourhood matter? Multilevel relationships between neighbourhood social fragmentation and mental health. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1993–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li LW, Xu H, Zhang Z, et al. An Ecological Study of Social Fragmentation, Socioeconomic Deprivation, and Suicide in Rural China: 2008–2010. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson AL, Ivory V, Breetzke G, et al. Are feelings of peace or depression the drivers of the relationship between neighbourhood social fragmentation and mental health in Aotearoa/New Zealand? Health Place 2014;26:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, et al. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pabayo R, Dunn EC, Gilman SE, et al. Income inequality within urban settings and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:997–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blakely TA, Kennedy BP, Glass R, Kawachi I. What is the lag time between income inequality and health status? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2000;54:318–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Services Research 1999;34:215–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn RS, Wise PH, Kennedy BP, et al. State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: cross sectional national survey. British Medical Journal 2000;321:1311–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Gilman SE. Income inequality among American states and the incidence of major depression. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:110–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blair A, Ross NA, Gariepy G, et al. How do neighborhoods affect depression outcomes? A realist review and a call for the examination of causal pathways. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:873–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Airaksinen J, Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, et al. Neighborhood effects in depressive symptoms, social support, and mistrust: Longitudinal analysis with repeated measurements. Soc Sci Med 2015;136–137:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr PB. Early neighborhood conditions and trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and into adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research 2018;35:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupere V, Leventhal T, Vitaro F. Neighborhood processes, self-efficacy, and adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav 2012;53:183–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colman I, Ataullahjan A. Life course perspectives on the epidemiology of depression. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 2010;55:622–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med 2010;40:899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buu A,. Wang W, Wang J, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Changes in women’s alcoholic, antisocial, and depressive symptomatology over 12 years: a multilevel network of individual, familial, and neighborhood influences. Development and Psychopathology 2011;23:325–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark C, Ryan L, Kawachi I, Canner MJ, Berkman L, Wright RJ. Witnessing community violence in residential neighborhoods: a mental health hazard for urban women. Journal of Urban Health 2008;85:22–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway KP, Vullo GC, Nichter B, et al. Prevalence and patterns of polysubstance use in a nationally representative sample of 10th graders in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:716–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn EC, Johnson RM, Green JG. The Modified Depression Scale (MDS): A Brief, No-Cost Assessment Tool to Estimate the Level of Depressive Symptoms in Students and Schools. School Ment Health 2012;4:34–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein AL, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Violence and substance use as risk factors for depressive symptoms among adolescents in an urban emergency department. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;40:276–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Luk JW, et al. Co-occurrence of victimization from five subtypes of bullying: physical, verbal, social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2010;35:1103–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment 2011;18:263–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin DE, Stucky B, Langer MM, et al. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Qual Life Res 2010;19:595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varni JW, Magnus B, Stucky BD, et al. Psychometric properties of the PROMIS (R) pediatric scales: precision, stability, and comparison of different scoring and administration options. Qual Life Res 2014;23:1233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.<Esri Crime Index Methodology.pdf>.

- 33.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, et al. Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychol Assess 2014;26:513–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olino TM, Yu L, McMakin DL, et al. Comparisons across depression assessment instruments in adolescence and young adulthood: an item response theory study using two linking methods. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blebu BE, Ro A, Kane JB, Bruckner TA. An examination of preterm birth and residential social context among black immigrant women in california, 2007–2010. Journal of Community Health 2018;. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Cohen-Cline H, Beresford SAA, Barrington WE, et al. Associations between neighbourhood characteristics and depression: a twin study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018;72:202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole H, Duncan DT, Ogedegbe G, Bennett S, Ravenell J. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage; neighborhood racial composition; and hypertension stage, awareness, and treatment among hypertensive black men in New York City: does nativity matter? Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.DeCuir J, Lovasi GS, El-Sayed A, Lewis CF. The association between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and high-risk injection behavior among people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2018;183:184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsui J, Gee GC, Rodriguez HP, Kominski GF, Glenn BA, Singhal R, Bastani R. Exploring the role of neighborhood socio-demographic factors on HPV vaccine initiation among low-income, ethnic minority girls. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2013;15:732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bureau USC. American Community Survey (ACS): Design and Methodology Report. In: Bureau USC, ed. Methodology Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pabayo R, Belsky J, Gauvin L, et al. Do area characteristics predict change in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 11 to 15 years? Soc Sci Med 2011;72:430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontenot KS,J, Kollar M Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017 In: Bureau USC, ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development 2002;73:1310–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crosier T, Butterworth P, Rodgers B. Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers. The role of financial hardship and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2007;42:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS, Green KM, Furr-Holden DM, Johnson RM, Milam AJ. The impact of the urban neighborhood environment on marijuana trajectories during emerging adulthood. Prevention Science 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Glynn K, Maclean H, Forte T, Cohen M. The association between role overload and women’s mental health. Journal of Women’s Mental Health 2009;18:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997;277:918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sampson RJ. Collective regulation of adolescent misbehavior: validation results from eighty Chicago neighborhoods. Journal of Adolescent Research 1997;12:227–44. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Development OfEC-oa. Glossary of Statistical Terms In: Development OfEC-oa, ed. Geneva, Switzerland: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bureau USC. Comparing 2006–2010 ACS 5-year and 2011–2015 ACS 5-year 2015.

- 51.Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, et al. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Social Science and Medicine 2008;26:1429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stirling K, Toumbourou JW, Rowland B. Community factors influencing child and adolescent depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:869–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Telzer EH, van Hoorn J, Rogers CR, et al. Social influence on positive youth development: a developmental neuroscience perspective. Advances in Child Behavior and Development 2018;54:215–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collaborators GDaH. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1603–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gariepy G, Blair A, Kestens Y, et al. Neighbourhood characteristics and 10-year risk of depression in Canadian adults with and without a chronic illness. Health and Place 2014;30:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]