Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for type 2 diabetes have uncovered >400 risk loci, primarily in populations of European and Asian ancestry. Here, we aimed to discover additional type 2 diabetes risk loci (including African-specific variants) and fine-map association signals by performing genetic analysis in African populations.

Methods

We conducted two type 2 diabetes genome-wide association studies in 4347 Africans from South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya and meta-analysed both studies together. Likely causal variants were identified using fine-mapping approaches.

Results

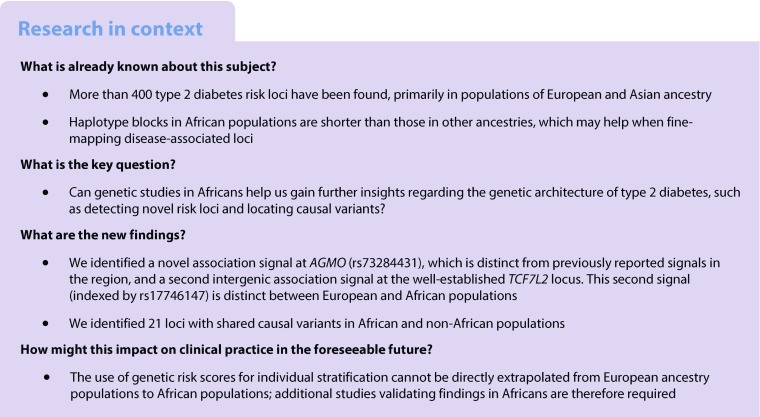

The most significantly associated variants mapped to the widely replicated type 2 diabetes risk locus near TCF7L2 (p = 5.3 × 10−13). Fine-mapping of the TCF7L2 locus suggested one type 2 diabetes association signal shared between Europeans and Africans (indexed by rs7903146) and a distinct African-specific signal (indexed by rs17746147). We also detected one novel signal, rs73284431, near AGMO (p = 5.2 × 10−9, minor allele frequency [MAF] = 0.095; monomorphic in most non-African populations), distinct from previously reported signals in the region. In analyses focused on 100 published type 2 diabetes risk loci, we identified 21 with shared causal variants in African and non-African populations.

Conclusions/interpretation

These results demonstrate the value of performing GWAS in Africans, provide a resource to larger consortia for further discovery and fine-mapping and indicate that additional large-scale efforts in Africa are warranted to gain further insight in to the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-019-4880-7) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Africa, Established loci, Fine-mapping, Genome-wide association study, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a major and growing public health problem, with Africa being the region with the fastest growing prevalence [1–3]. In addition to lifestyle, genetic factors play a major role in susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. To date, type 2 diabetes genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have uncovered over 400 risk signals, primarily in populations of European [4, 5] and Asian [6–8] ancestry, with more limited efforts in Hispanics/Latinos [9–11] and African-Americans [12, 13]. Thus far, type 2 diabetes genetic studies in populations from Africa, which are genetically and environmentally diverse, have focused on the replication of established loci [14].

Here, we conducted a meta-analysis of type 2 diabetes in up to 4347 African participants to identify genetic risk factors associated with type 2 diabetes in Africans, evaluate previously reported loci and utilise the finer-grained linkage disequilibrium (LD) pattern of African populations to fine-map-associated loci.

Methods

Study participants

South African Zulu individuals were type 2 diabetes cases and controls from two studies: the Durban Diabetes Study (DDS) and the Durban Diabetes Case Control study (DCC). DDS was a population-based cross-sectional study of non-pregnant urban black African adults of Zulu descent, aged >18 years, residing in Durban, South Africa [15, 16]. Further details are provided in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) Methods. Additional type 2 diabetes cases from the same ethnic group and locality were obtained from the DCC, which included individuals with type 2 diabetes attending a diabetes clinic. Type 2 diabetes was defined using WHO criteria [15, 16]. The combined type 2 diabetes cases and controls from DDS and DCC were aggregated into a single Zulu study.

The Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) study comprised individuals from sub-Saharan Africa, enrolled from university medical centres in Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya. A person with type 2 diabetes was identified using ADA criteria or if he or she was receiving treatment for type 2 diabetes. Probable cases of type 1 diabetes were excluded and controls had no evidence of diabetes based on fasting/2 h glucose or symptoms of suggestive diabetes [14]. The characteristics of the Zulu and AADM participants are shown in ESM Table 1.

Genotyping, quality control and imputation

In total, 2707 African individuals of Zulu descent (2003 women and 704 men) were genotyped using the Illumina Multi-Ethnic Genotyping Array (Illumina, Illumina Way, San Diego, CA, USA). Following sample and variant quality control (QC) (ESM Methods), there were 2578 samples with genotype and phenotype information (1602 cases and 976 controls) and 1,434,868 variants (1,395,345 autosomal and 39,523 on the X chromosome).

The AADM samples were genotyped on the Affymetrix Axiom PANAFR SNP array as described previously [14]. After QC (ESM Methods), there were 1031 cases and 738 controls and 2,141,465 variants (2,080,378 autosomal and 61,087 on the X chromosome) in AADM.

All samples were imputed to a merged panel of 1000 Genomes phase 3 [17] and African samples using IMPUTE2 [18] (Zulu) or positional Burrows–Wheeler transform (PBWT) [19] using the Sanger imputation server (AADM) (ESM Methods). We retained all imputed SNPs with MAF > 0.01 and imputation information score > 0.4 that were also in a newer version of the imputation panel.

Association analysis

In Zulu samples, association with type 2 diabetes was performed for each variant based on the imputation dosage using a linear mixed model that accounts for the presence of related individuals and any population structure implemented in genome-wide efficient mixed-model association (GEMMA) [20], adjusting for age, sex and BMI. The kinship matrix was estimated from directly genotyped autosomal variants with MAF > 0.01. In AADM, association with type 2 diabetes was performed for each variant based on the imputation dosage using an additive logistic regression model implemented in SNPTEST v2.5.2 [21] (Oxford University, Oxford, UK www.well.ox.ac.uk/~gav/resources/snptest_v2.5.2_linux_x86_64_dynamic.tgz) adjusting for age, sex, BMI and the first three principal components (PCs) to account for population structure. The number of PCs adjusted for in AADM was determined by testing for the number of PCs using the minimum average partial test [22]. The first three PCs were determined to be significant and thus were adjusted for in the association analyses.

Meta-analysis, signal selection and fine-mapping

Meta-analysis of the Zulu and AADM summary statistics for shared variants was performed using a fixed-effects meta-analysis (weighted for effective sample size) in METAL [23] and we applied double genomic-control correction (ESM Methods). To identify distinct signals of association, we performed approximate conditional analyses using the joint model implemented in genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) [24, 25] and variants with p < 2.5 × 10−8 in the joint model were selected as signals with genome-wide significance [26]. To estimate meta-analysis ORs, we also performed an inverse-variance-weighted meta-analysis using an approximation of the allelic logeOR and variance from the linear model in the Zulu samples [27], and the logeOR estimates obtained directly from SNPTEST for the AADM samples.

We used FINEMAP [28] (C. Benner, University of Helsinki, Finland www.christianbenner.com/finemap_v1.1_x86_64.tgz) to identify likely causal variants within 500 kb either side of the most significant variant at the loci TCF7L2 and AGMO in the African meta-analysis and in Europeans [5] (ESM Methods).

Comparison with established loci

We used ‘direct’ (same lead variant with p < 0.05 and directionally consistent) and ‘local’ (locus-level) detection to explore the extent to which existing GWAS signals (almost all from non-African samples) were detected in the African GWAS (ESM Methods, ESM Table 2). We used two complementary approaches to test for enrichment of signals detected using the ‘direct’ approach: (1) a binomial test taking significance (p < 0.05) and direction of effect into account; and (2) enrichment of directly detected variants, accounting for the properties of the variants in GARFIELD [29] (ESM Methods). For loci demonstrating ‘direct’ and/or ‘local’ detection between our African data and existing GWAS signals (ESM Table 2), we performed co-localisation analyses implemented in the R package ‘coloc’ [30] using summary statistics from the largest available European type 2 diabetes GWAS at the time of analysis [5] (default prior for causal variant sharing set to 0.5) (ESM Methods). Using the weighted allele frequencies and sample sizes from the African meta-analysis and previously reported effect sizes, we estimated the power to detect established variants at the significance thresholds p < 0.05 and p < 2.5 × 10−8 using R version 3.3.0 [31] (ESM Table 2).

We also performed genetic risk score (GRS) analyses to harvest association information from multiple variants. GRSs were calculated as the total number of risk alleles in subsets of the 102 variants at established loci from existing GWAS studies of type 2 diabetes (published before May 2018), primarily in populations of European and Asian ancestry (ESM Table 2).

Testing association of INS-variable number tandem repeat with type 2 diabetes

We used the haplotypic information for INS-variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) generated in African-descent individuals by Stead et al (2003) [32] to impute INS-VNTR lineages in the Zulu and AADM samples and perform a meta-analysis (ESM Methods). Conditional analysis was performed to detect distinct association signals by inclusion of dosages of the lead type 2 diabetes variants as covariates in the regression model.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval was obtained for each participating cohort: the Institutional Review Board for each AADM participating institution and the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal for DCC (BF078/08) and DDS (BF030/12). DDS also had UK National Research Ethics Service approval (reference: 14/WM/1061). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

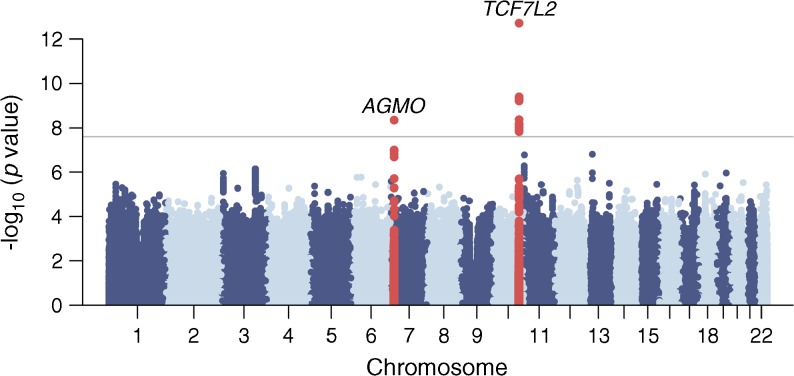

A total of 12,148,595 variants (genotyped or imputed) overlapping the Zulu and AADM samples were included in the meta-analysis of type 2 diabetes. We identified two genome-wide-significant (p < 2.5 × 10−8) [26] association signals (Table 1, Fig. 1). A further 37 distinct signals were detected at 2.5 × 10−8 ≤ p < 1 × 10−5 (ESM Table 3).

Table 1.

Type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci with genome-wide significance in combined Zulu and AADM meta-analysis

| SNP | Chr. | Position (bp) | Allelesa | Locus/nearest gene(s) | Zulu GWAS | AADM GWAS | Meta-analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Other | RAF | p value | OR (95% CI) |

RAF | p value | OR (95% CI) |

Weighted mean RAF | p value | OR (95% CI) |

Heterogeneity p value | ||||

| rs7903146 | 10 | 114,758,349 | T | C | TCF7L2 | 0.381 | 7.9 × 10−7 |

1.25 (1.15, 1.37) |

0.319 | 1.5 × 10−8 |

1.58 (1.34, 1.85) |

0.356 | 5.3 × 10−13 |

1.32 (1.22, 1.43) |

0.26 |

| rs73284431 | 7 | 15,434,230 | G | C | AGMO | 0.924 | 2.1 × 10−8 |

1.59 (1.35, 1.87) |

0.878 | 0.011 |

1.31 (1.06, 1.62) |

0.905 | 5.2 × 10−9 |

1.48 (1.30, 1.69) |

0.093 |

Genome-wide significance, p<2.5×10−8

aAlleles are aligned to the forward strand of NCBI Build 37

Chr., chromosome; RAF, risk allele frequency; heterogeneity p value: p value from Cochran’s Q test for heterogeneity

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plot of the type 2 diabetes meta-analysis results. The horizontal grey line corresponds to p=2.5×10−8 and loci reaching that significance threshold (variants within 500 kb distance of those with p<2.5×10−8) are shown in red. Gene labels correspond to the nearest/most biologically plausible gene

The most significant signal for type 2 diabetes association, rs7903146 at TCF7L2 (p = 5.3 × 10−13), has been widely reported in other ethnic groups [9, 13, 33, 34]. The second signal, rs73284431, (p = 5.2 × 10−9, risk allele frequency = 0.093, specific to individuals of African descent) maps to an intron of AGMO, 491 kb upstream of the DGKB transcription start site. The region is already known to harbour two independent GWAS signals for type 2 diabetes [5] and fasting glucose [35, 36] (denoted by rs10238625 and rs10276674, 132 kb apart and >379 kb from rs73284431), both of them distinct from our lead variant based on exact conditional analyses (ESM Table 4).

Despite not reaching genome-wide significance, the association with rs12277475 (p = 2.0 × 10−7, ESM Table 3) near the INS (insulin) gene was of interest given previous reports of a significant African-American type 2 diabetes association signal at rs3842770 [37], 28 kb away. The two lead variants are not in LD (r2 ~ 0.03) in 2959 African samples from the merged imputation reference panel [13], and reciprocal exact conditional analyses confirmed our signal was not being driven by the reported African-American association signal (ESM Table 5). In our data, rs3842770 showed a more modest association with type 2 diabetes (p = 0.0020 in the joint meta-analysis) than rs12277475. The rs12277475 association was also not driven by the previously reported East Asian type 2 diabetes signal (rs7107784) in this region [7] (ESM Table 5).

In type 1 diabetes, robust associations with variants at INS-IGF2 have been localised to the INS-VNTR mini-satellite within the INS gene promoter [38, 39]; in Europeans, an association between VNTR class III alleles and type 2 diabetes predisposition has been reported in historical candidate gene studies [40, 41]. To explore the relationship between the rs12277475 signal and VNTR variation, we imputed INS-VNTR genotypes using flanking SNP haplotypes (see Methods and ESM Methods). Of the nine distinct lineages with MAF > 0.01 detected in both Zulu and AADM, the strongest associations were observed for lineage W (p = 0.0001, OR 1.24, ESM Table 6) and lineage K (p = 0.0057, OR 0.85, ESM Table 6). Type 2 diabetes association results for lineages W and K and lead variant rs12277475 were largely unchanged in reciprocal conditional analyses (ESM Tables 7 and 8 [Zulu and AADM, respectively]). We conclude that rs12277475 is likely to represent a novel type 2 diabetes association in this region, independent of previous genome-wide significant associations detected in the close vicinity, and is not acting through the VNTR.

Fine-mapping of TCF7L2 and AGMO

Fine-mapping of TCF7L2 and AGMO identified the most significant variants from the meta-analysis, rs7903146 and rs73284431, as the most likely causal variants with posterior probabilities of association of 0.996 and 0.828, respectively (ESM Table 9). These were the only SNPs in the top configuration of causal variants from FINEMAP (ESM Figs. 1 and 2). At TCF7L2, a second plausible causal variant, rs17746147 (r2 = 0.009 with rs7903146 estimated from the African samples in the merged panel), with posterior probability of association of 0.295, was contained in the second most likely configuration of causal variants (ESM Table 9, ESM Fig. 1). The 99% credible intervals and corresponding results in Europeans are presented in ESM Table 9. Fine-mapping results were comparable when using the stepwise approximate Bayes factor approach [42] (data not shown).

Detection of established loci

We explored the extent to which previously reported type 2 diabetes association signals could be detected in African-descent individuals. Based on the previously reported effect sizes and the effect allele frequency and sample size from our African meta-analysis, we had sufficient power (80%) to detect three signals (TCF7L2, DNER and SRR) at genome-wide significance (p < 2.5 × 10−8) (ESM Table 2). Only the TCF7L2 variant reached genome-wide significance in our study, whereas both variants in DNER (rs1861612) and SRR (rs391300), originally discovered in Pima Indians and East Asians, respectively, had p > 0.1 (ESM Table 2).

So far, five African-American type 2 diabetes-associated signals have been reported, three of which (two in KCNQ1 and one in HMGA2) were first reported in Europeans and two (INS-IGF2 and HLA-B) were first reported in African-Americans (ESM Table 2) [13]. In our meta-analysis, we detected only a nominal association for the African-American INS-IGF2 signal (rs3842770, p = 0.0020, ESM Table 2). However, we identified another signal at this locus (rs12277475, p = 2.0 × 10−7, ESM Table 3) that is independent of the African-American signal (rs3842770), and this signal co-localises with association in Europeans (posterior probability H4 = 1, ESM Table 10).

In ‘direct’ analyses (same lead variant with p < 0.05 and directionally consistent in the African meta-analysis), we detected 12 of 100 lead variants (ESM Table 2) at established type 2 diabetes loci first reported in non-African ancestry individuals, significantly more than expected by chance (binomial test of enrichment p = 8.14 × 10−6, GARFIELD enrichment OR [95% CI] 3.07 (1.50, 6.28), p = 0.002) (ESM Methods). In addition, detection of ‘local’ signals (at least one variant within the 200 kb region flanking the previously reported index variant [100 kb either side] reaching nominal significance [p < 0.05] after correcting for the effective number of independent tests) identified 11 type 2 diabetes loci, two of them overlapping signals also detected with the direct approach (ESM Table 2). Genetic co-localisation analyses suggested that African and non-African populations share the same causal variants at all 21 loci showing direct or local detection in our data (posterior probability H4 > 0.8, ESM Table 10).

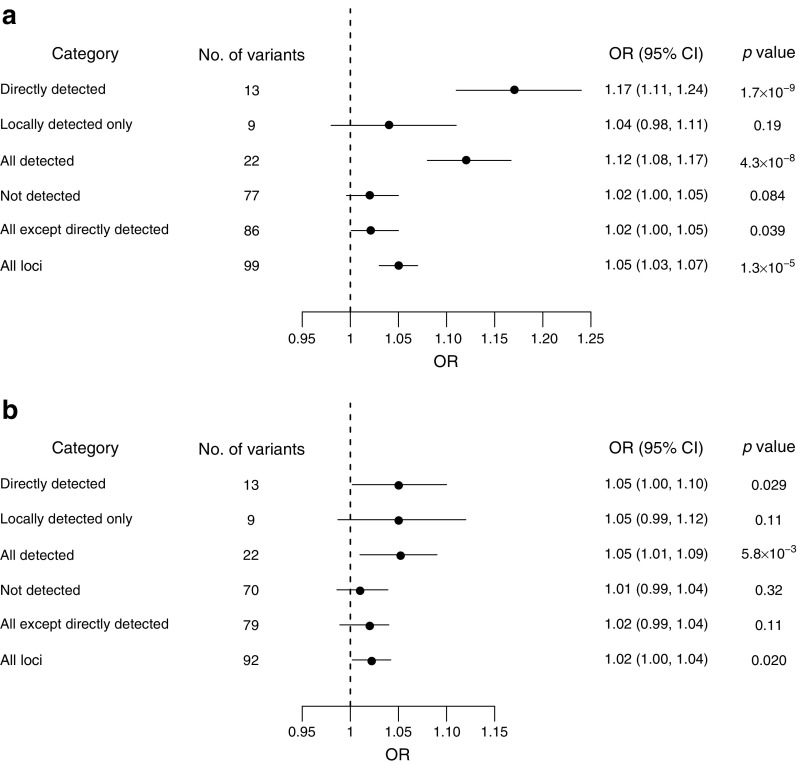

We constructed GRSs by combining subsets of 102 previously established loci (including those first reported in African-ancestry individuals) and tested for association with type 2 diabetes (ESM Table 2). A GRS constructed from these variants showed significant association with type 2 diabetes in the Zulu (OR 1.05 per risk allele, p = 1.3 × 10−5, Fig. 2a) and AADM samples (OR 1.02 per risk allele, p = 0.020, Fig. 2b), an association driven primarily by the 13 directly detected variants (Zulu, OR 1.17, p = 1.7 × 10−9; AADM, OR 1.05, p = 0.029). GRSs based on the variants detected by only the local approach or the variants not detected by either approach were not significantly associated with type 2 diabetes in African samples (p = 0.19 and 0.084, respectively in the Zulu; p = 0.11 and 0.32, respectively in AADM) (Fig. 2). These results show there is a shared genetic contribution to type 2 diabetes at established loci directly detected in Africans.

Fig. 2.

(a) Associations between the GRSs constructed from the subsets of established type 2 diabetes variants and type 2 diabetes in the Zulu samples. (b) Associations between the GRSs constructed from the subsets of established type 2 diabetes variants and type 2 diabetes in the AADM samples. Please see ESM Table 2 for details of categories

Discussion

In a meta-analysis of type 2 diabetes from two African populations, we replicated the widely reported association at TCF7L2 (rs7903146) and identified a novel association signal at AGMO (rs73284431) that is distinct from previously reported signals in the region.

Using direct and local detection, we showed the transferability of 21 established type 2 diabetes signals discovered in non-African ancestry populations to Africans and that causal variants at those loci were shared across ancestries. For example, the lead SNP at TCF7L2, rs7903146, shared between African and European ancestries, has been refined as the causal variant by examining LD blocks of West African, Danish, Icelandic and American-African populations [43, 44]. Although the mechanisms through which TCF7L2 variation increases type 2 diabetes risk are largely unknown, recent evidence implicates altered incretin signalling [45].

We also found evidence for ancestry-specific signals, such as the second intergenic association signal at TCF7L2 that is distinct between European and African populations (indexed by rs17746147). In addition, although not reaching genome-wide significance, we detected an association at the INS-IGF2 locus (rs12277475) that appears to be distinct from the previously reported signals in African-Americans and East Asians in the region. We found no evidence of association between the lead variant and VNTR variation in our study, suggesting that the association at INS-IGF2 in our data is not acting through the VNTR.

In summary, our findings highlight the importance of diverse ancestries for uncovering novel biology. Larger African meta-analyses are warranted to gain further insight on the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 556 kb)

(XLSX 68 kb)

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource (Application Number 9161).

Abbreviations

- AADM

Africa America Diabetes Mellitus

- DCC

Durban Diabetes Case Control study

- DDS

Durban Diabetes Study

- GRS

Genetic risk score

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- PC

Principal component

- QC

Quality control

- VNTR

Variable number tandem repeat

Contribution statement

JC, MeS, AA, FP, IB, MIM, AM, EW, CNR and AAM wrote the manuscript. JC, MeS, AA, TC, GC, APM, IB, MIM, AM and EW contributed to the analysis of the data. AA, FP, CP, APD, GC, AAM, EHY, MaS and CNR contributed to the acquisition of data. AAM, APD and CNR contributed to the phenotyping. FP, IB, MIM, CNR and AAM are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Funding

MIM is a Wellcome Senior Investigator and a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator. MIM acknowledges support for this work from Wellcome (090532, 203141, 106130, 098381, 090367), MRC (G0601261) and NIH (U01DK105535, R01DK098032, U01DK085545). The DCC was funded by Servier South Africa, the South African Sugar Association and the Victor Daitz Foundation. CNR, AA, GC and APD are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health in the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health (CRGGH). The CRGGH is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Center for Information Technology and the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health (1ZIAHG200362). IB acknowledges funding from Wellcome (WT206194). The study sponsors were not involved in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Data availability

Summary statistics from the meta-analysis will be available to download from the EBI GWAS Catalog (www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/downloads/summary-statistics).

Duality of interest

TC owns shares in Novo Nordisk, Roche and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. IB and spouse own stock in GlaxoSmithKline and Incyte Corporation. MIM serves on advisory panels for Pfizer, Novo Nordisk and Zoe Global; has received honoraria from Pfizer, Novo Nordisk and Lilly; has stock options in Zoe Global; and has received research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Servier and Takeda. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ji Chen, Meng Sun, Adebowale Adeyemo and Fraser Pirie contributed equally to this study.

Anubha Mahajan, Eleanor Wheeler, Charles N. Rotimi and Ayesha A. Motala are joint senior authors.

Contributor Information

Anubha Mahajan, Email: anubha@well.ox.ac.uk.

Eleanor Wheeler, Email: eleanor.wheeler@mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk.

Charles N. Rotimi, Email: rotimic@mail.nih.gov

Ayesha A. Motala, Email: motala@ukzn.ac.za

References

- 1.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1513–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation (2015) Diabetes Atlas (7th Edition). Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org

- 3.Mbanya JC, Motala AA, Sobngwi E, Assah FK, Enoru ST. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2254–2266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:981–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott RA, Scott LJ, Magi R, et al. An expanded genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Europeans. Diabetes. 2017;66(11):2888–2902. doi: 10.2337/db16-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kooner JS, Saleheen D, Sim X, et al. Genome-wide association study in individuals of South Asian ancestry identifies six new type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):984–989. doi: 10.1038/ng.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura M, Takahashi A, Yamauchi T, et al. Genome-wide association studies in the Japanese population identify seven novel loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):10531. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho YS, Chen CH, Hu C, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies eight new loci for type 2 diabetes in east Asians. Nat Genet. 2011;44:67–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi Q, Stilp AM, Sofer T, et al. Genetics of type 2 diabetes in U.S. Hispanic/Latino individuals: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Diabetes. 2017;66(5):1419–1425. doi: 10.2337/db16-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parra EJ, Below JE, Krithika S, et al. Genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in a sample from Mexico City and a meta-analysis of a Mexican-American sample from Starr County, Texas. Diabetologia. 2011;54(8):2038–2046. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2172-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consortium STD, Williams AL, Jacobs SB, et al. Sequence variants in SLC16A11 are a common risk factor for type 2 diabetes in Mexico. Nature. 2014;506(7486):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer ND, McDonough CW, Hicks PJ, et al. A genome-wide association search for type 2 diabetes genes in African Americans. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng Maggie C. Y., Shriner Daniel, Chen Brian H., Li Jiang, Chen Wei-Min, Guo Xiuqing, Liu Jiankang, Bielinski Suzette J., Yanek Lisa R., Nalls Michael A., Comeau Mary E., Rasmussen-Torvik Laura J., Jensen Richard A., Evans Daniel S., Sun Yan V., An Ping, Patel Sanjay R., Lu Yingchang, Long Jirong, Armstrong Loren L., Wagenknecht Lynne, Yang Lingyao, Snively Beverly M., Palmer Nicholette D., Mudgal Poorva, Langefeld Carl D., Keene Keith L., Freedman Barry I., Mychaleckyj Josyf C., Nayak Uma, Raffel Leslie J., Goodarzi Mark O., Chen Y-D Ida, Taylor Herman A., Correa Adolfo, Sims Mario, Couper David, Pankow James S., Boerwinkle Eric, Adeyemo Adebowale, Doumatey Ayo, Chen Guanjie, Mathias Rasika A., Vaidya Dhananjay, Singleton Andrew B., Zonderman Alan B., Igo Robert P., Sedor John R., Kabagambe Edmond K., Siscovick David S., McKnight Barbara, Rice Kenneth, Liu Yongmei, Hsueh Wen-Chi, Zhao Wei, Bielak Lawrence F., Kraja Aldi, Province Michael A., Bottinger Erwin P., Gottesman Omri, Cai Qiuyin, Zheng Wei, Blot William J., Lowe William L., Pacheco Jennifer A., Crawford Dana C., Grundberg Elin, Rich Stephen S., Hayes M. Geoffrey, Shu Xiao-Ou, Loos Ruth J. F., Borecki Ingrid B., Peyser Patricia A., Cummings Steven R., Psaty Bruce M., Fornage Myriam, Iyengar Sudha K., Evans Michele K., Becker Diane M., Kao W. H. Linda, Wilson James G., Rotter Jerome I., Sale Michèle M., Liu Simin, Rotimi Charles N., Bowden Donald W. Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies in African Americans Provides Insights into the Genetic Architecture of Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10(8):e1004517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adeyemo AA, Tekola-Ayele F, Doumatey AP, et al. Evaluation of genome wide association study associated type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci in Sub Saharan Africans. Front Genet. 2015;6:335. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hird TR, Pirie FJ, Esterhuizen TM, et al. Burden of diabetes and first evidence for the utility of HbA1c for diagnosis and detection of diabetes in urban black South Africans: The Durban Diabetes Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hird TR, Young EH, Pirie FJ, et al. Study profile: the Durban Diabetes Study (DDS): a platform for chronic disease research. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2016;1:e2. doi: 10.1017/gheg.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durbin R. Efficient haplotype matching and storage using the positional Burrows-Wheeler transform (PBWT) Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1266–1272. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):821–824. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shriner D. Improved eigenanalysis of discrete subpopulations and admixture using the minimum average partial test. Hum Hered. 2012;73(2):73–83. doi: 10.1159/000335899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Ferreira T, Morris AP, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):369–375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pe’er I, Yelensk R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(4):381–385. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook JP, Mahajan A, Morris AP. Guidance for the utility of linear models in meta-analysis of genetic association studies of binary phenotypes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(2):240–245. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benner C, Spencer CCA, Havulinna AS, Salomaa V, Ripatti S, Pirinen M. FINEMAP: efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(10):1493–1501. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iotchkova V, Ritchie GRS, Geihs M, et al. GARFIELD classifies disease-relevant genomic features through integration of functional annotations with association signals. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):343–353. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0322-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace C, Rotival M, Cooper JD, et al. Statistical colocalization of monocyte gene expression and genetic risk variants for type 1 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(12):2815–2824. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from www.R-project.org/ (accessed 11 May 2016)

- 32.Stead JD, Hurles ME, Jeffreys AJ. Global haplotype diversity in the human insulin gene region. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2101–2111. doi: 10.1101/gr.948003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi F, Serizawa M, Yamamoto K, et al. Confirmation of multiple risk loci and genetic impacts by a genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1690–1699. doi: 10.2337/db08-1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabassum R, Chauhan G, Dwivedi OP, et al. Genome-wide association study for type 2 diabetes in Indians identifies a new susceptibility locus at 2q21. Diabetes. 2013;62(3):977–986. doi: 10.2337/db12-0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42(2):105–132. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang JY, Sim X, Wu Y, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies novel variants associated with fasting plasma glucose in East Asians. Diabetes. 2015;64(1):291–298. doi: 10.2337/db14-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng MC. Genetics of type 2 diabetes in African Americans. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(10):74. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0651-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett ST, Wilson AJ, Esposito L, et al. Insulin VNTR allele-specific effect in type 1 diabetes depends on identity of untransmitted paternal allele. The IMDIAB group. Nat Genet. 1997;17(3):350–352. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bell GI, Horita S, Karam JH. A polymorphic locus near the human insulin gene is associated with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1984;33(2):176–183. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed S, Bennett ST, Huxtable SJ, Todd JA, Matthews DR, Gough SC. INS VNTR allelic variation and dynamic insulin secretion in healthy adult non-diabetic Caucasian subjects. Diabet Med. 1999;16(11):910–917. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ong KK, Phillips DI, Fall C, et al. The insulin gene VNTR, type 2 diabetes and birth weight. Nat Genet. 1999;21(3):262–263. doi: 10.1038/6775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakefield J. A Bayesian measure of the probability of false discovery in genetic epidemiology studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):208–227. doi: 10.1086/519024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helgason A, Palsson S, Thorleifsson G, et al. Refining the impact of TCF7L2 gene variants on type 2 diabetes and adaptive evolution. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):218–225. doi: 10.1038/ng1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer ND, Hester JM, An SS, et al. Resequencing and analysis of variation in the TCF7L2 gene in African Americans suggests that SNP rs7903146 is the causal diabetes susceptibility variant. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):662–668. doi: 10.2337/db10-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan S, Kaur V, Chamarthi B, et al. TCF7L2 genetic variation augments incretin resistance and influences response to a sulfonylurea and metformin: the Study to Understand the Genetics of the Acute Response to Metformin and Glipizide in Humans (SUGAR-MGH) Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):554–561. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 556 kb)

(XLSX 68 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Summary statistics from the meta-analysis will be available to download from the EBI GWAS Catalog (www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/downloads/summary-statistics).