Abstract

Histone H3.3 is a developmentally essential variant encoded by two independent genes in human (H3F3A and H3F3B). While this two-gene arrangement is evolutionarily conserved, its origins and function remain unknown. Phylogenetics, synteny and gene structure analyses of H3.3 genes from 32 metazoan genomes indicate independent evolutionary paths for H3F3A and H3F3B. While H3F3B bears similarities with H3.3 genes in distant organisms and with canonical H3 genes, H3F3A is sarcopterygian-specific and evolves under strong purifying selection. Additionally, H3F3B codon-usage preferences resemble those of broadly expressed genes and ‘cell differentiation-induced’ genes, while codon-usage of H3F3A resembles that of ‘cell proliferation-induced’ genes. We infer that H3F3B is more similar to the ancestral H3.3 gene and likely evolutionarily adapted for a broad expression pattern in diverse cellular programs, while H3F3A adapted for a subset of gene expression programs. Thus, the arrangement of two independent H3.3 genes facilitates fine-tuning of H3.3 expression across cellular programs.

Subject terms: Molecular evolution, Evolutionary biology

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, which plays a dual role of genome compaction and regulation1. Basic repeating units of chromatin, called nucleosomes, comprise 147 bp of DNA wrapped around a core that is formed by histone proteins of four types (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4), which are conserved in eukaryotic organisms including animals2,3, fungi3,4 and plants3. The histones fall into two major types: replication-dependent (RD) canonical histones and replication-independent (RI) non-canonical variants. The RI histone variants have diverse biological roles and are part of the epigenetic regulation of genome function5–7. Unlike the canonical histones that are encoded by co-regulated gene clusters (histone loci)2, RI variants are encoded by individual genes that are regulated similarly to other protein coding genes.

One of the most studied histone variants is H3.3, which replaces canonical histone H3 and functionally can be associated with both gene activation8,9 and silencing10–12. H3.3 variant is expressed and deposited throughout the cell-cycle independent of DNA replication13–15. In the human genome H3.3 can be transcribed from either of two independent genes (H3F3A and H3F3B), which are located on different chromosomes, 1 and 17, respectively. These genes differ at the nucleotide level both within introns and exons, although they encode exactly the same amino-acid sequence. Presence of multiple independent genes encoding H3.3 is also conserved in other organisms, including distant species such as the fruit fly16. Moreover, despite absolute conservation at the protein level, the mutational profiles of H3F3A and H3F3B genes in human cancers differ substantially. For instance, mutation K27M was reported in H3F3A but not in H3F3B in brainstem gliomas17, while mutation K36M is more frequently observed in H3F3B in bone cancers, such as chondroblastoma18,19. These mutations have been reported to occur at high frequency, and the biological mechanisms through which they can contribute to cancer malignancy have been recently under intense investigation19–21. The regulatory genomic elements associated with these genes are also distinct, and the over-expression of H3F3A but not H3F3B is implicated to have an effect in lung cancer through aberrant H3.3 deposition22. Taken together, these observations indicate that while H3F3A and H3F3B encode the same protein product, they are under different regulatory mechanisms and play distinct roles.

Evolution of H3.3 encoding genes was analyzed in Drosophila species23; however, on a larger scale, the biological function and evolutionary history of such two-gene organization remains unclear, despite its biomedical significance21,24. To approach these questions, we compared the sequences and genomic arrangements of the H3.3 genes from 32 metazoan genomes. Using phylogenetics, sequence identity, gene structure and synteny analyses, we infer that H3F3A is a sarcopterygian-specific (tetrapod and lobe-finned fish) gene, while H3F3B is of more ancient origin. Furthermore, analysis of codon-usage preferences in each of the H3.3 genes revealed that H3F3B is evolutionarily adapted for broad expression patterns across diverse cellular programs, including cell differentiation, while H3F3A is more fine-tuned for a specific transcriptional program associated with cell proliferation. This observation of coding sequence optimization for distinct transcriptional programs provides insight into why both H3F3A and H3F3B have been maintained over the course of evolution, even though they encode an identical amino-acid sequence.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses of H3.3-encoding genes in metazoa

We identified the H3.3 coding sequences from the genomes of 32 metazoa organisms, primarily vertebrates, and used them in our analysis. We observed that two ‘independent’ genes (i.e. located in different genomic loci and controlled by distinct, non-overlapping promoters) encode histone H3.3 in all analyzed organisms except for coelacanth where H3.3 is encoded by three genes, and actinopterygii (ray-finned fish lineage) where it is encoded by either three or five genes (Table S1). The high number of H3.3 genes in actinopterygian most likely resulted from whole genome duplication events25–28 and partial chromosome duplication events29–31 that occurred in this lineage during evolution. With these exceptions, the arrangement of two H3.3 genes is widespread among vertebrates. Such an arrangement can also be observed in some invertebrate metazoa, e.g. flies and nematodes, as well as in more distant eukaryotes, e.g. some plants32. Remarkably, the encoded amino-acid sequence is identical in all analyzed vertebrates and Drosophila melanogaster (Fig. S1). The existence of two independent genes that encode an identical amino-acid sequence allows us to focus on analysis of the evolutionary pressure acting on these genes at the nucleotide rather protein level.

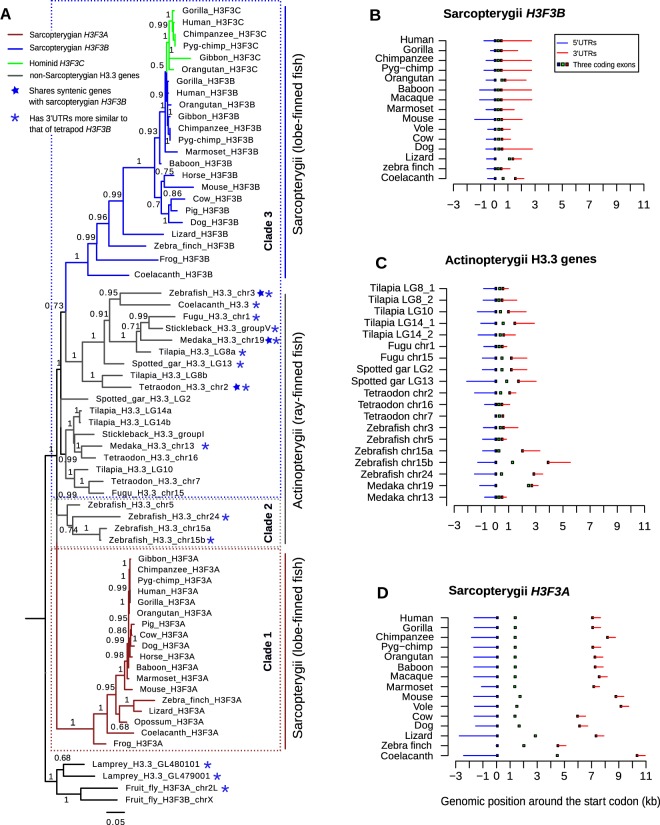

Next, we analyzed the phylogenetic relationship of the H3.3 genes in metazoa. The coding sequences of these genes form several distinct groups in the phylogenetic tree, including two major groups (clades 1 and 3), one minor group (clade 2) and outgroups of lamprey and fly H3.3 genes (Fig. 1A). Clade 1 (shown in brown) consists exclusively of sarcopterygian H3F3A genes (the lobe-finned fish lineage, including all tetrapods and coelacanth). Clade 3 comprises all sarcopterygian H3F3B genes (blue) along with the majority of actinopterygian H3.3 genes (gray) and the third coelacanth H3.3 gene. We note that this clade also includes a ‘hominid-specific’ gene H3F3C (green), which emerged as a recent retro-transposition of H3F3B33. H3F3C encodes another replacement histone from H3 family, H3.5, that differs from the histone H3.3 by several amino-acids, and it was included in this analysis for further comparison. The confident assignment of H3F3C to clade 3 that contains H3F3B genes (branch support = 1), highlights that the distinction between the coding sequences (CDS) of the genes forming clades 1 (H3F3A) and 3 (H3F3B) is substantial and evolutionary stable even though these genes encode the same protein H3.3 (no amino-acid difference). Finally, clade 2 contains the remaining actinopterygian H3.3 genes that cluster neither with sarcopterygian H3F3A nor with sarcopterygian H3F3B. This analysis gives the first evidence that, compared to sarcopterygian H3F3A, sarcopterygian H3F3B is likely more evolutionarily related to actinopterygian H3.3 genes.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analyses of H3.3-encoding genes. (A) Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the evolution of H3.3 genes in vertebrates. Three clades were distinguished. Clade 1 comprises sarcopterygian H3F3A genes (brown); Clade 3 comprises sarcopterygian H3F3B (blue) together with actinopterygian H3.3 (gray). Clade 2 consists of other actinopterygian H3.3 genes that cluster with neither clade 1 nor clade 3. Numbers along tree branches represent approximate log-likelihood ratio test values for branch support. Blue stars mark non-tetrapod genes with synteny to tetrapod H3F3B, and blue asterisks mark non-tetrapod genes whose 3′UTRs are more similar to 3′UTRs of tetrapod H3F3B than those of tetrapod H3F3A. (B–D) Intron-exon structure of sarcopterygian H3F3B, actinopterygian H3.3 genes and sarcopterygian H3F3A. All genes are drawn from 5′ to 3′ and are aligned at the start codon, position 0. The blue and red lines represent the 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTRs respectively, and the squares in the middle represent the locations of protein-coding exons.

The observed relationship between H3F3B and actinopterygian genes was confirmed by comparison of the intron-exon structure of all H3.3-encoding genes throughout the species. In sarcopterygian genomes H3F3B is generally shorter, spanning ~2–4 kb with a total intron length of ~0.16–1 kb (Fig. 1B). H3F3B structure is similar to that of actinopterygian H3.3 (gene length is approximately ~2–6 kb and total intron length is ~0.16–4 kb; Fig. 1C). The H3F3A gene structure is noticeably different, with the gene length spanning ~9–13 kb and total intron length being ~4.5–10 kb (Fig. 1D). Thus, the intron-exon structure of sarcopterygian H3F3B, and not sarcopterygian H3F3A, is more similar to the actinopterygian H3.3 genes and H3.3 genes in lamprey, fly and worm, consistent with our previous observations.

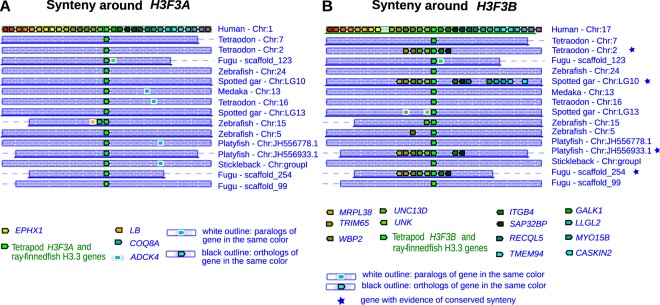

To further support these results, we carried out synteny analysis to determine whether genes around H3F3A or H3F3B are evolutionary conserved in non-tetrapod organisms. We first used Genomicus 80.01, a web-based synteny visualization tool that uses comparative genomic data from the Ensembl database34. Comparison between human and actinopterygii shows no syntenic genes conserved around human H3F3A and H3.3 genes in actinopterygian species (Fig. 2A), but at least six syntenic genes can be identified around human H3F3B and H3.3 genes in four actinopterygian species (fugu, platyfish, spotted gar, and tetraodon) (marked with a blue star, Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Synteny around H3F3A and H3F3B genes. (A,B) Synteny conservation analysis around human H3F3A (A) and H3F3B (B) genes performed using selected actinopterygian genomes. Human H3F3A and H3F3B and actinopterygian H3.3 are placed at the center of each plot (green block). A black outline represents an ortholog of a gene in the same color, while a white outline represents a paralog of a gene in the same color. A blue star indicates an actinopterygian organisms in which syntenic genes around the H3.3 gene are also conserved around the human H3.3 gene.

We extended this analysis to all tetrapods and distant metazoa (lampreys, flies and worms), by implementing a flexible synteny detection method allowing the user to quantitatively measure the degree of gene conservation around loci of interest in two genomes (see Methods). Specifically, we compared 30 genes upstream and downstream of each of the H3.3 genes and the degree of gene conservation was determined by sequence identities computed independently for both coding sequences and translated amino-acid sequences. While we found clear evidence of synteny conservation around both H3.3 genes in tetrapods, it was consistently higher around H3F3A than H3F3B. For instance, the ratios of syntenic genes around H3F3A to those around H3F3B were 25/17, 12/6, 12/6 for the human-mouse, human-lizard and human-zebra finch comparisons respectively (Fig. S2A). At the same time, we found no synteny conservation around tetrapod H3F3A and actinopterygian H3.3. In contrast, for H3F3B we found the same six genes conserved between tetrapods and one of the tetraodon H3.3 genes, which were detected by Genomicus, and a weak conservation of these genes in zebrafish and medaka (marked with blue stars in Fig. S2A,B and Fig. 1A).

From these observations, we conclude that orthologs of mammalian H3F3A and H3F3B are present in the coelacanth genome (i.e. throughout the sarcopterygian lineage). Sarcopterygian H3F3B is evolutionarily related to many actinopterygian H3.3 genes while sarcopterygian H3F3A seems to have no counterpart in the actinopterygian lineage (Fig. 1A). We infer that the sarcopterygian-specific H3F3A clade with a long and well-supported branch (branch support = 1, Fig. 1A), is consistent with one of the following scenarios: (i) the counterpart of H3F3A was lost in the actinopterygian lineage soon after the actinopterygian-sarcopterygian split, or (ii) since the actinopterygian/sarcopterygian split either an existing or a newly emerged H3.3 gene underwent rapid evolution towards the current H3F3A form. We aimed to distinguish these possibilities by the analysis described below.

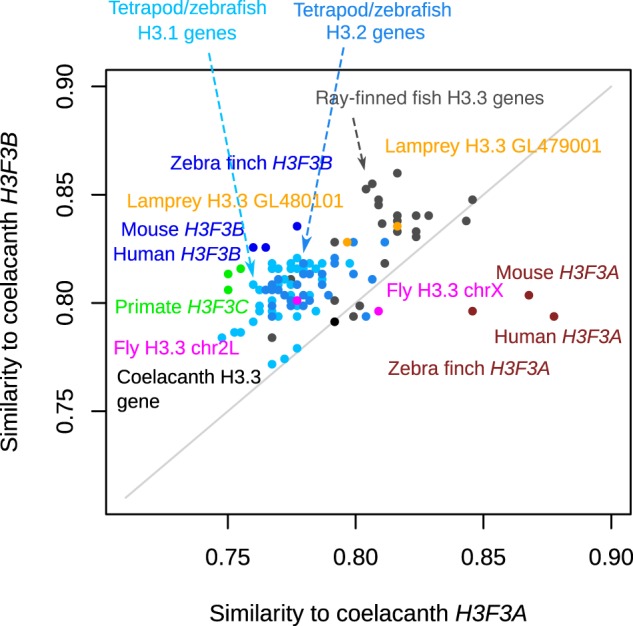

Comparison of H3.3 genes between sarcopterygians and distant metazoa

One can expect that if H3F3A were lost in actinopterygians, both H3F3A and H3F3B would exhibit roughly equal similarity to H3.3 genes in more distant metazoa. Thus, to resolve the scenarios described above we directly compared the similarity of sarcopterygian H3F3A and H3F3B to the H3.3 genes of actinopterygians and distant organisms (lamprey and fly) (Fig. 3). We also included in this analysis genes encoding the RD canonical histones H3.1 and H3.2 because these genes emerged from an ancient gene duplication event that resulted in a separation of replication-dependent and replication-independent histones35. For sarcopterygian genes in this analysis, we used coelacanth H3F3A and H3F3B. Coelacanth can be expected to show more similarity to non-sarcopterygian organisms than other sarcopterygians, in part because its protein-coding genes evolved twice as slow as those in tetrapods36, which makes it especially suitable for this comparison.

Figure 3.

Comparison of coelacanth H3.3 genes to related genes in sarcopterygian and non-sarcopterygian lineages. Sequence similarity was estimated for the CDS of coelacanth H3.3 genes (H3F3A, x-axis and H3F3B, y-axis) and CDS of H3.3 genes from other sarcopterygian and more distant organisms (actinopterygians, lamprey, fly). Additionally, CDS of tetrapod and zebrafish H3.1 and H3.2 genes were included in this analysis. Each point represents a gene and the organism name is written in the matching color. The sequence similarity represents the percentage of the identical nucleotides in the sequence.

This analysis revealed that most of the actinopterygian H3.3 genes and RD H3.1 and H3.2-encoding genes of bony vertebrates (tetrapods and zebrafish) are more similar to sarcopterygian H3F3B than to H3F3A (Fig. 3). This trend further extends to both lamprey H3.3 genes and one fly H3.3 (chr2L) gene. As expected, H3F3C is also more similar to coelacanth H3F3B than H3F3A as expected. Overall, only tetrapod H3F3A genes can be confidently ‘assigned’ to coelacanth H3F3A. As a control, we have repeated this analysis using tetrapods (human, mouse and zebra finch) H3F3A and H3F3B genes instead of coelacanth genes and observed similar trends (Fig. S3). Overall, these results reveal that in comparison to H3F3A, sarcopterygian H3F3B is more similar to the H3.3 genes in distant metazoa and to RD H3 genes, suggesting that H3F3B is more similar to the ancestral form of the H3.3 gene.

Additional supporting evidence for this hypothesis comes from the comparison of the 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of the H3.3 genes, performed by pairwise-alignment followed by sequence identity calculation with gap-exclusion (Fig. S4). UTRs are among the most conserved non-coding sequences in eukaryotes37,38, and the 3′UTRs of H3.3 genes are similarly evolutionarily conserved (~60–80% identity) among tetrapods and actinopterygians. We validated this approach by confirming that it produces results consistent with the phylogenetic analysis of H3.3 coding sequences when applied to genes from clades 1 and 3 (Fig. 1A), which include sarcopterygian H3.3 genes. When we applied this approach to genes from other clades, we observed that in every analyzed non-sarcopterygian organism (actinopterygian species, lamprey, fly and worm), at least one H3.3 gene has higher similarity of its 3′UTRs to that of tetrapod H3F3B (~75% identity) compared to tetrapod H3F3A (~60% identity) (Fig. S4A,B). These organisms are marked with blue asterisks in Fig. 1A. There were no instances of a non-tetrapod H3.3 3′UTR being more similar to the 3′UTR of tetrapod H3F3A.

Collectively, our results indicate that gene H3F3A is sarcopterygii-specific, while gene H3F3B is evolutionary related to actinopterygian H3.3 genes as well as to the H3.3 genes in more distant metazoans. Furthermore, our results suggest that H3F3B is more directly related to the ancestral form of the H3.3 gene. We find that the possibility of a lineage-specific loss of H3F3A in the actinopterygians is less plausible than the hypothesis of an existing or newly emerged H3.3 gene copy that underwent rapid evolution to become H3F3A in sarcopterygian lineage.

Distinct selection pressures within tetrapod H3F3A and H3F3B CDS

The conservation of the arrangement of two distinct genes encoding the same protein suggests functional significance. To investigate how potential functional differences between these two genes may be reflected in their genomic sequences, we measured selective pressures operating at the nucleotide level in H3F3A and H3F3B. Due to the lack of variation among H3.3 protein sequences in analyzed organisms, the methods based on non-synonymous and synonymous substitution rates often used for detection of natural selection39–41 are not suitable. Instead, we investigate purifying selection operating on H3F3A and H3F3B genes based on the degree of conservation of coding nucleotide-sequence in tetrapod organisms.

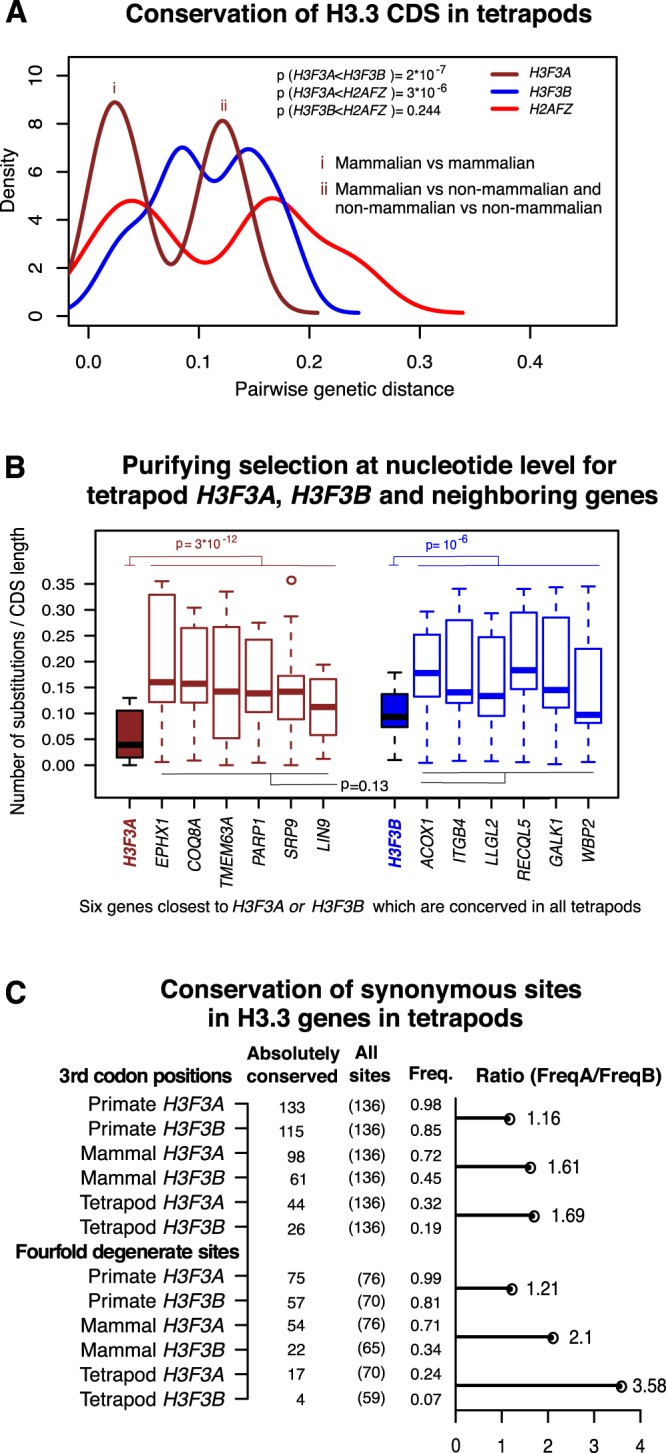

We calculated pairwise genetic distances between the tetrapod H3.3 genes, defined here as the numbers of the observed nucleotide substitutions divided by the CDS length (i.e. the “nucleotide substitution score”). As a control, we also included in this analysis the H2AFZ gene, which encodes the conserved replacement histone H2A.Z. Overall, we observed that while H3F3B is not significantly more conserved than H2AFZ (P = 0.244, Mann-Whitney’s test), H3F3A is under a stronger selection pressure as compared to both H3F3B and H2AFZ (P = 2*10−7, P = 3*10−6 respectively, Fig. 4A). Also, for the organisms included in this analysis, the distributions of the nucleotide substitution scores are bimodal for all three genes, with smallest substitution scores observed within mammalian group (Fig. 4A). This trend is especially pronounced for H3F3A, as further suggested by the analysis of substitution scores for this gene performed within mammalian and non-mammalian groups of organisms independently (Fig. S5A,B).

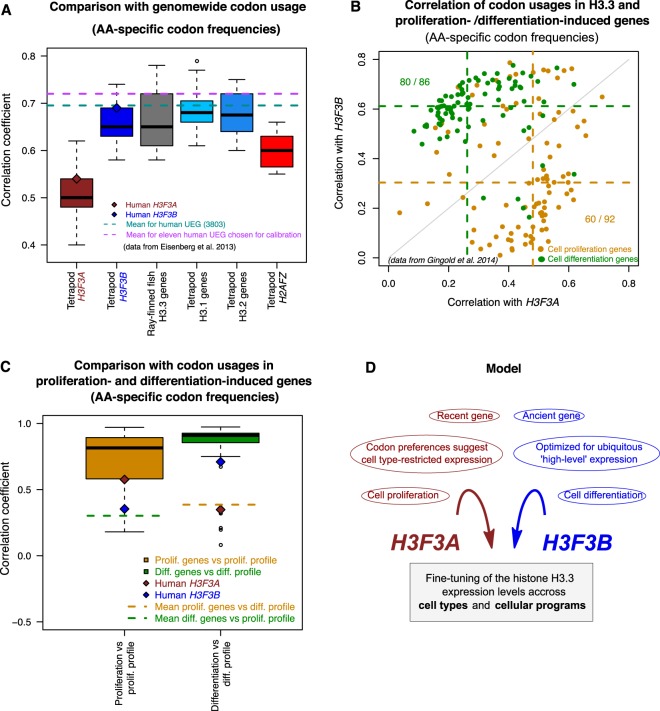

Figure 4.

Conservation of coding sequences in tetrapod histone variant genes. (A) Pairwise nucleotide substitution scores (genetic distances) computed for two H3.3 genes (H3F3A, brown and H3F3B, blue), and H2AFZ gene (red) which was included in this analysis for comparison. The analysis was performed for tetrapod genomes. Distribution shifting to the left (smaller genetic distances) indicates higher conservation of the corresponding gene. “i” marks the peak of the bimodal distribution corresponding to the pairwise comparisons involving only mammalian organisms, while “ii” marks the peak corresponding to the pairwise comparisons involving mammalian and non-mammalian organisms as well as comparisons of non-mammalian organisms to each other. (B) Pairwise nucleotide substitution scores for H3F3A in tetrapod genomes (box plot filled in brown), H3F3B in tetrapod genomes (filled in blue), and their neighboring genes (brown and blue borders respectively). Both H3F3A and H3F3B are significantly highly conserved relative to their surrounding genes (Wilcox sum rank test P = 2.9 * 10−12 and P = 10−6 respectively). No significant difference in conservation level between genes around H3F3A and those around H3F3B (P = 0.13). (C) Absolute nucleotide conservation in CDS of the H3.3 genes in tetrapod lineages. Top panel: all 3rd codon position; bottom panel: the fourfold degenerate sites (i.e. sites where any possible nucleotide substitution is synonymous). Columns show the number of absolutely conserved sites for a given group of organisms, the total number of 3rd codon positions or fourfold degenerate sites, and the corresponding frequencies of absolutely conserved sites. The horizontal bar represents the H3F3A/H3F3B over-representation of absolutely conserved sites.

To rule out that the difference in sequence conservation of H3.3-encoding genes is determined by the conservation of entire loci encompassing H3F3A or H3F3B, rather than these genes themselves, we extended the analysis described above to six genes around each of the H3.3-encoding genes. We found no significant difference in conservation level between genes around H3F3A and those around H3F3B (Fig. 4B).

At the same time, both H3F3A and H3F3B are significantly more conserved than the neighboring genes (P = 3*10−12 and P = 10−6 respectively), with H3F3A exhibiting the highest level of conservation among the analyzed genes. This indicates that tetrapod H3F3A evolves under stronger purifying selection at the nucleotide level than H3F3B, H2AFZ or neighboring genes.

Not surprisingly, given that the H3.3 genes encode the same amino-acid sequence, most substitutions were observed in the 3rd position of the codon. Interestingly, we found that sarcopterygian H3F3B genes have generally higher GC-content at 3rd codon position (GC3) as compared to sarcopterygian H3F3A (Fig. S6). The high GC3 in H3F3B genes mirrors actinopterygian H3.3 and RD H3.1/H3.2-encoding genes, while H2AFZ genes, similarly to H3F3A genes, have lower GC3 (Fig. S6). Thus, based on this metric, H3F3B is more similar to ancestral H3.3 and RD H3 histone genes, consistent with our previous phylogenetic analyses.

To refine this analysis further, we compared the degree of nucleotide conservation at wobble positions (i.e. 3rd codon positions where synonymous nucleotide substitutions are commonly detected) between H3F3A and H3F3B gene alignments made of (i) all tetrapods, (ii) mammals, and (iii) primates (Fig. 4C). We also separately considered a special case of wobble positions, so-called ‘fourfold degenerate’ sites, i.e. 3rd codon positions at which all possible nucleotide substitutions can occur without changing the encoded amino-acid; hence such fourfold degenerate sites are under no selection pressure for amino-acid maintenance. A wobble position was considered “absolutely conserved” if the nucleotide at that site is conserved in the whole alignment (i.e. in all organisms).

In all groups, we consistently observed that there are more absolutely conserved 3rd codon positions in H3F3A than H3F3B in all analyzed groups of species (Fig. 4C). This trend is most pronounced for fourfold degenerate sites (cf. horizontal bars in Fig. 4C). In addition, such an over-representation is more pronounced for groups containing evolutionary distant organisms e.g. FreqA/FreqB ratio for fourfold degenerate sites is 1.21, 2.1, 3.58 for primates, mammals, and tetrapods respectively. This observation suggests that stronger selection on synonymous sites in H3F3A than H3F3B is a stable phenomenon, deeply rooted in the tetrapod lineage.

These findings revealed that there is a layer of selection pressure against nucleotide substitutions operating on both H3F3A and H3F3B CDSs, driven not by the maintenance of amino-acid sequence but maintenance of specific codons. Thus, our results suggest that codon usage is under selection pressure among H3.3 genes. While this selection pressure is stronger in H3F3A than in H3F3B, we infer that both genes have evolutionary adapted for distinct codon usage preferences, and we investigate this phenomenon in more detail below.

Differences in codon usage between H3.3 encoding genes

The expression and abundance of transfer RNA (tRNA) vary substantially in human cell types42. This variation correlates with codon usage preferences and plays a role in translational control43–45. Furthermore, codon usage may differ between genes specialized in different cellular processes such as cell proliferation and cell differentiation43. Thus, an analysis of the codon usage in H3.3 genes can provide information on their functional specialization among cellular gene expression programs.

To this end, we estimated the correlation between codon usage frequencies in each H3.3 gene and the genome-wide codon usage frequencies from each tetrapod genome. Similar to a previously published study43, we defined these codon usage frequencies (hereby referred to as “amino-acid specific codon frequencies”) so that they represent the probability that a codon is used when the amino-acid encoded by this codon appears in the protein product sequence (see Methods). Since different genes are expressed in different cell types, we expect that the codon usage frequencies computed for the entire genome (‘genome-wide codon usage frequencies’) would correlate strongly with the codon usage frequencies of genes showing broad expression patterns. In line with this hypothesis, codon usage frequencies in a set of human genes specifically selected for their ubiquitous expression in multiple cell types46 correlated with genome-wide frequencies with the Pearson’s correlation coefficient equal about 0.695 (Fig. 5A). Application of this approach to the H3.3 genes revealed that the correlation estimated for the human H3F3B gene (r = 0.69) is close to the benchmark value observed for the ubiquitously expressed genes (UEG), while the correlation for the H3F3A gene is considerably lower (r = 0.54). Furthermore, all tetrapod H3F3B genes, actinopterygian H3.3 genes, and RD H3.1/H3.2 genes (the latter are expressed in all dividing cells) show higher correlation with genome-wide frequencies than either H3F3A or H2AFZ genes do (Fig. 5A). We confirmed that similar results are observed when codon usage is defined directly as the frequency of every codon in a gene, without accounting for amino-acid abundance in the product (“codon frequencies” in Fig. S7A). Based on these findings, we conclude that, as compared to H3F3A, H3F3B is evolutionarily more optimized for a broad expression pattern.

Figure 5.

Distinct codon usage preferences in the H3.3 genes (based on ‘amino-acid specific codon frequencies’). (A) Correlation between codon usage in the genes specified at x-axis and the genome-wide codon usage. The box plots represent the lineage distributions of correlation coefficients calculated for the ‘amino-acid specific codon frequencies’ of a corresponding gene with those estimated genome-wide (e.g. all tetrapod H3F3A genes vs. genome-wide frequencies). The brown and blue diamonds provide reference for human H3F3A and H3F3B respectively. The dashed cyan and magenta lines represent average correlations computed for the full set of human ubiquitously expressed genes (UEG; cyan) and a subset of these genes that have been proposed for calibration due to their highly uniform and strong expression across human cell types (magenta)46. (B) Correlation of human H3F3A and H3F3B codon usage frequencies with those computed for the genes associated with cell proliferation (orange) and cell differentiation (green)43. Each dot represents an individual gene from the corresponding group. The dotted lines indicate the correlation coefficient medians for each group and the H3.3 gene. (C) Benchmarking of the codon usage frequencies in the H3.3 genes relative to the frequencies estimated for the genes from the cell proliferation and differentiation groups. Boxplots represent correlation values for the amino-acid specific codon frequencies of individual cell proliferation genes or cell differentiation genes with the overall profiles estimated for their respective groups. Dashed lines show the mean values of the correlations of individual genes from one group with the opposite group profile (e.g. mean for the correlations of the codon usages of the proliferation genes with the overall differentiation profile). The brown and blue diamonds indicate correlation values for the human H3F3A and H3F3B genes. (D) A model illustrating the possible role of the evolutionary conserved arrangement of the two genes (H3F3A and H3F3B) encoding the same protein (H3.3) in fine-tuning of this protein expression.

To gain further insight into the evolutionary adaptation of the H3.3 genes, we compared their codon usage frequencies to those estimated for the two groups of genes shown to be involved in different transcriptional programs (‘cell proliferation’ and ‘cell differentiation’ genes43). Specifically, we computed pairwise correlations between the amino-acid specific codon frequencies of H3.3 genes and the individual genes associated with each of transcriptional program (orange and green dots in Fig. 5B, S7B). This analysis showed that, by this metric, H3F3A shares greater similarity with the ‘proliferation’ genes, while H3F3B is more similar to the ‘differentiation’ genes (P = 6.9*10−12 and P = 8.3*10−12 respectively, Mann-Whitney’s test; Fig. S7C,D). We confirmed these results in a similar analysis based on direct codon frequencies which are not corrected for amino-acid abundance (Fig. S7E,F).

To benchmark the similarity between the codon usage of an individual gene and the codon usage profiles associated with different transcriptional programs, we correlated codon usages of individual proliferation- and differentiation-induced genes to both codon usage profiles (Fig. 5C). Comparison of the H3.3 genes with these benchmarks showed that H3F3A falls within 25th percentile of proliferation-associated genes when they are evaluated against codon usage profile of their own group (r = 0.58). The similarity of this gene to the differentiation group is low and it is on par with the average similarity observed for the proliferation-induced genes when they are compared to the codon usage profile of the differentiation group. In line with our previous results, H3F3B exhibits an opposite trend: its codon usage correlates better with differentiation gene profile (r = 0.71 vs. r = 0.35 for differentiation and proliferation profiles respectively). We note however, that the H3F3B ranks relatively low among differentiation-induced in terms of their similarity to the group profile.

Based on these results, we conclude that H3F3A and H3F3B were evolutionary optimized for distinct transcriptional programs. In this analysis we tested two programs that have been described in literature43. While other programs may exist, our observations indicate better fitness of H3F3A for the proliferation program and, arguably to a lesser extent, better fitness of H3F3B for differentiation program. We also found that, similar to H3F3B (but not H3F3A), differentiation-induced genes correlate strongly with the genome-wide codon usage (r = 0.88), which suggests a broad expression profile. Thus, while H3F3B does not rank high among the differentiation-induced genes, taken together our findings show that this gene is broadly expressed in cell types, including differentiated cells. Overall, we report that despite encoding identical protein sequence, H3F3A and H3F3B have distinct evolutionary histories and are optimized for distinct transcriptional programs at the codon usage level, as illustrated in Fig. 5D.

Discussion

The H3.3 histone is currently a subject of intense research due to its biological and biomedical significance21,24; however, evolution of the genes encoding this protein is not fully understood. In this study, we addressed this issue and studied the evolutionary history of the H3.3-encoding genes from a diverse set of metazoan genomes. All analyzed genomes harbor multiple genes (two in most cases, H3F3A and H3F3B) that encode an identical amino-acid sequence. We have shown that, despite being highly conserved at the amino-acid sequence level, H3.3-encoding genes are subject to selection pressure at the DNA sequence level, which is related to their cellular function.

Several lines of evidence stemming from phylogenetic analysis, as well as analyses of the gene structure, synteny and codon usage (Figs 1–3 and 5) indicate that H3F3A is specific for the sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) lineage, whereas H3F3B exist in all sarcopterygians and bears similarity to H3.3 genes in actinopterygians (ray-finned fish) and jawless fish and with the vertebrate RD H3.1/H3.2 genes that diverged much earlier. These results suggest that H3F3B is more similar to the ancestral form of H3.3 gene than H3F3A, which could be a product of a duplication event occurring after actinopterygian-sarcopterygian split. However, we cannot completely exclude that H3F3A could have been lost in actinopterygians and other lineages and additional studies are required to trace the exact origin of each H3.3 gene.

Despite absolute conservation at the amino-acid sequence level, tetrapod H3F3A and H3F3B are under varying degrees of purifying selection at codon synonymous sites, resulting in distinct codon usage profiles (Fig. 5). Codon preferences in the H3.3-encoding genes have been previously discussed for Drosophila species23. In this study, we focused on the possible functional significance of differential codon usage for fine-tuning of the human H3.3 genes. Specifically, our analysis revealed that codon usage in H3F3B is similar to that of ‘cell differentiation-induced’ genes, in contrast to the codon usage in H3F3A, which is similar to that of ‘cell proliferation-induced genes’43. We note that while proliferation-induced genes are active in a specific pathway, one can expect that ‘differentiation-induced’ genes would show a broad expression profile as a group, because they can be associated with various pathways in different cell types. This is also in line with our observation that codon usage of H3F3B, but not of H3F3A, is similar to that of UEGs which are active throughout cell types (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, similarly to the UEGs, H3F3B genes feature a compact structure, with short introns (Fig. 1B)47,48. Given that we analyzed only two transcriptional programs, it is possible that H3F3A and/or H3F3B would show similar or even better fit for other programs. However, our results allow us to conclude that H3F3A and H3F3B genes are evolutionary optimized for different transcriptional programs through codon usage preferences and intron-exon organization.

In summary, the H3.3 genes provide a unique ‘study case’, in which the protein sequence remains constant over the course of evolution for an extended time period, allowing analysis of the selection operating at nucleotide level. Such analysis reveals an evolutionary mechanism of nucleotide sequence optimization for the fine-tuning of gene expression in specific cellular programs. In this work we have not addressed the questions of possible differences in the regulation of mRNA transcription from each of the H3.3 genes or posttranslational modifications that histones produced from the individual genes may preferentially bear. Answering these questions would require additional studies and they will undoubtedly shed new light on the biomedical significance of the existence of independent H3.3 genes.

Methods

Phylogenetics analysis

Sequences and annotations of the genes encoding histone variant H3.3 in different species, as well as other genes used in this study were obtained from Ensembl and NCBI-RefSeq databases. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using PHYML3.1 software49, with an approximate likelihood ratio test (Chi2-based) for branch supports and GTR nucleotide substitution model.

Synteny analysis

Synteny around H3F3A and H3F3B genes in selected set of vertebrate genomes was detected using a the web application Genomicus version 80.01, that uses Ensembl comparative genomic data (http://genomicus.biologie.ens.fr/genomicus)34. To supplement the Genomicus-based analysis and test for synteny between tetrapods and distant organisms, an additional method was used. Specifically, we estimated the degree of conservation of the CDS and the translated amino-acid sequences of the genes located in the vicinity of H3.3-encoding genes. For each organism included in this analysis, we considered either 30 genes downstream and 30 genes upstream of each of the H3.3 encoding genes or the maximal number of genes within +/−1.5 Mb of the corresponding H3.3 gene. These genes were compared in a pairwise manner to 30 genes downstream and the 30 genes upstream of H3F3A and H3F3B in the human genome. The annotated genomic sequences were obtained from Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html), and CDS and amino-acid sequences of these genes were extracted using Biopython tools (www.biopython.org). Pairwise comparison of nucleotide and protein sequences was done by aligning two sequences using alignment program MUSCLE50 and computing sequence identity scores. The maximal identity score for each of the analyzed genes was reported in the plots presented in Fig. S2A,B. Additionally, to achieve higher sensitivity of this analysis in non-tetrapod organisms, we combined the H3.3-proximal genes from all tetrapods listed in Fig. S1, and used them in the procedure described above instead of using only 60 human H3.3-proximal genes.

3′UTRs comparison

3′UTR sequences of actinopterygian H3.3 genes were compared to those of tetrapod H3F3A and H3F3B to find similarities. The UTRs sequences were obtained from each organism’s genomic DNA based on H3.3 gene annotations. Comparison was performed through alignment of each pair of 3′UTR sequences using MUSCLE50 and computing their sequence identity scores. Briefly, the identity scores are calculated as 1-(M/N) where M is the number of mismatching nucleotides and N the total number of positions along the alignment at which neither sequence has a gap character. Other parameters for the alignment performed with MUSCLE were used at their default values. Since gaps (indels) in alignments can substantially influence final identity scores51, we excluded them from calculations to insure that high UTR sequence variability (due to insertions and deletions) does not deflate the scores and affect comparisons.

Codon usage analysis

Two metrics of codon usage were used, the ‘amino-acid specific codon frequencies’ and ‘codon frequencies’. The amino-acid specific codon frequencies represent codon occurrences normalized for amino-acid abundance43, i.e. divided by the number of times the corresponding amino-acid appears in the protein sequence. This metric corrects for potential amino-acid usage biases and represents the probability that a codon will be used given that the corresponding amino-acid is used. The second metric, ‘codon frequencies’, were computed by dividing the codon occurrences by the total number of codons in the gene (i.e. normalized by the length of the encoded amino-acid sequence). The codon usage profiles were computed for different gene sets (proliferation-induced43, differentiation-induced43). Genome-wide codon counts were obtained from (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Marjorie Oettinger for valuable discussions and Mattia Lion, Behfar Aldehali, and Erica Larschan for critical reading of the manuscript and many insightful comments.

Author Contributions

B.M.M. and M.Y.T. designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data. M.A.B. provided expertise on sequence analysis. B.M.M., M.A.B. and M.Y.T. wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

All the data are available upon request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44800-4.

References

- 1.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The Role of Chromatin during Transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzluff WF, Gongidi P, Woods KR, Jin J, Maltais LJ. The human and mouse replication-dependent histone genes. Genomics. 2002;80:487–98. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postberg J, Forcob S, Chang W-J, Lipps HJ. The evolutionary history of histone H3 suggests a deep eukaryotic root of chromatin modifying mechanisms. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hereford L, Fahrner K, Woolford J, Rosbash M, Kaback DB. Isolation of yeast histone genes H2A and H2B. Cell. 1979;18:1261–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90237-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banaszynski LA, Allis CD, Lewis PW. Histone variants in metazoan development. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:662–74. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber CM, Henikoff S. Histone variants: dynamic punctuation in transcription. Genes Dev. 2014;28:672–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.238873.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenderski W, Maze I. Histone turnover and chromatin accessibility: Critical mediators of neurological development, plasticity, and disease. BioEssays. 2016;38:410–419. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mito Y, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Genome-scale profiling of histone H3.3 replacement patterns. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1090–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin C, Felsenfeld G. Nucleosome stability mediated by histone variants H3.3 and H2A.Z. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1519–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1547707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiyama T, Suzuki O, Matsuda J, Aoki F. Dynamic replacement of histone H3 variants reprograms epigenetic marks in early mouse embryos. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santenard A, et al. Heterochromatin formation in the mouse embryo requires critical residues of the histone variant H3.3. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:853–62. doi: 10.1038/ncb2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voon HPJ, Wong LH. New players in heterochromatin silencing: histone variant H3.3 and the ATRX/DAXX chaperone. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1496–1501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagami H, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G, Nakatani Y. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 Complexes Mediate Nucleosome Assembly Pathways Dependent or Independent of DNA Synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1191–200. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray-Gallet D, et al. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akhmanova AS, et al. Structure and expression of histone H3.3 genes in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila hydei. Genome. 1995;38:586–600. doi: 10.1139/g95-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturm D, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleven AHG, et al. Mutation Analysis of H3F3A and H3F3B as a Diagnostic Tool for Giant Cell Tumor of Bone and Chondroblastoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015;39:1576–83. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behjati S, et al. Distinct H3F3A and H3F3B driver mutations define chondroblastoma and giant cell tumor of bone. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1479–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuen BTK, Knoepfler PS. Histone H3.3 Mutations: A Variant Path to Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan F, Shi Y. Histone H3.3 and cancer: A potential reader connection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:6814–6819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418996111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S-M, et al. Histone variant H3F3A promotes lung cancer cell migration through intronic regulation. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12914. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuo, Y. & Kakubayashi, N. Epigenetics Evolution and Replacement Histones: Evolutionary Changes at Drosophila H3.3A and H3.3B. J. Phylogenetics Evol. Biol. 4, 1000174 (2016).

- 24.Mohammad F, Helin K. Oncohistones: drivers of pediatric cancers. Genes Dev. 2017;31:2313–2324. doi: 10.1101/gad.309013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasauer SMK, Neuhauss SCF. Whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes and its evolutionary consequences. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2014;289:1045–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schartl M, et al. The genome of the platyfish, Xiphophorus maculatus, provides insights into evolutionary adaptation and several complex traits. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:567–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crow KD, Smith CD, Cheng JF, Wagner GP, Amemiya CT. An independent genome duplication inferred from Hox paralogs in the American paddlefish-a representative basal ray-finned fish and important comparative reference. Genome Biol. Evol. 2012;4:937–953. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexandrou MA, Swartz BA, Matzke NJ, Oakley TH. Genome duplication and multiple evolutionary origins of complex migratory behavior in Salmonidae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;69:514–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volff J-N. Genome evolution and biodiversity in teleost fish. Heredity (Edinb). 2005;94:280–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volff JN, et al. Jule from the fish Xiphophorus is the first complete vertebrate Ty3/Gypsy retrotransposon from the Mag family. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:101–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postlethwait JH, et al. Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res. 2000;10:1890–902. doi: 10.1101/gr.164800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui J, et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary, and Expression Analyses of Histone H3 Variants in Plants. Biomed Res. Int. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/341598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenk R, Jenke A, Zilbauer M, Wirth S, Postberg J. H3.5 is a novel hominid-specific histone H3 variant that is specifically expressed in the seminiferous tubules of human testes. Chromosoma. 2011;120:275–285. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louis Alexandra, Nguyen Nga Thi Thuy, Muffato Matthieu, Roest Crollius Hugues. Genomicus update 2015: KaryoView and MatrixView provide a genome-wide perspective to multispecies comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;43(D1):D682–D689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterborg JH. Evolution of histone H3: emergence of variants and conservation of post-translational modification sites. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90:79–95. doi: 10.1139/o11-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amemiya CT, et al. The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature. 2013;496:311–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siepel A. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Research. 2005;15(8):1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie X, et al. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3′ UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murrell B, et al. FUBAR: a fast, unconstrained bayesian approximation for inferring selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1196–205. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delport Wayne, Scheffler Konrad, Botha Gordon, Gravenor Mike B., Muse Spencer V., Kosakovsky Pond Sergei L. CodonTest: Modeling Amino Acid Substitution Preferences in Coding Sequences. PLoS Computational Biology. 2010;6(8):e1000885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pond SLK, Frost SDW. Datamonkey: rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2531–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dittmar KA, Goodenbour JM, Pan T. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:2107–2115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gingold H, et al. A Dual Program for Translation Regulation in Cellular Proliferation and Differentiation. Cell. 2014;158:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plotkin JB, Robins H, Levine AJ. Tissue-specific codon usage and the expression of human genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12588–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404957101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quax TEF, Claassens NJ, Söll D, van der Oost J. Codon Bias as a Means to Fine-Tune Gene Expression. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. Human housekeeping genes, revisited. Trends Genet. 2013;29:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. Human housekeeping genes are compact. Trends Genet. 2003;19:362–365. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Castillo-Davis CI, Mekhedov SL, Hartl DL, Koonin EV, Kondrashov FA. Selection for short introns in highly expressed genes. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:415–418. doi: 10.1038/ng940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010;59:307–21. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muhire BM, Varsani A, Martin DP. SDT: a virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available upon request.