Summary

Sclerostin (SOST) is an extracellular Wnt signaling antagonist which negatively regulates bone mass. Despite this, the expression and function of SOST in skeletal tumors remain poorly described. Here, we first describe the immunohistochemical staining pattern of SOST across benign and malignant skeletal tumors with bone or cartilage matrix (n = 68 primary tumors). Next, relative SOST expression was compared to markers of Wnt signaling activity and osteogenic differentiation across human osteosarcoma (OS) cell lines (n = 7 cell lines examined). Results showed immunohistochemical detection of SOST in most bone-forming tumors (90.2%; 46/51) and all cartilage-forming tumors (100%; 17/17). Among OSs, variable intensity and distribution of SOST expression were observed, which highly correlated with the presence and degree of neoplastic bone. Patchy SOST expression was observed in cartilage-forming tumors, which did not distinguish between benign and malignant tumors or correlate with regional morphologic characteristics. Finally, SOST expression varied widely between OS cell lines, with more than 97-fold variation. Among OS cell lines, SOST expression positively correlated with the marker of osteogenic differentiation alkaline phosphatase and did not correlate well with markers of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. In summary, SOST is frequently expressed in skeletal bone- and cartilage-forming tumors. The strong spatial correlation with bone formation and the in vitro expression patterns are in line with the known functions of SOST in nonneoplastic bone, as a feedback inhibitor on osteogenic differentiation. With anti-SOST as a potential therapy for osteoporosis in the near future, its basic biologic and phenotypic consequences in skeletal tumors should not be overlooked.

Keywords: SOST, Wnt signaling, Sarcoma, Osteosarcoma, Enchondroma, Chondrosarcoma

1. Introduction

Sclerostin (SOST) is an extracellular Wnt signaling antagonist with high endogenous expression in osteocytes [1,2]. Human disorders of SOST expression and activity result in bone overgrowth in rare autosomal recessive syndromes, including sclerosteosis and Van Buchem disease. SOST is well described to negatively regulate osteogenesis and bone mass [1,2], and targeted Sost deletion in mice results in a high-Bone Mineral Density phenotype with increased bone strength [3]. Consequently, significant interests exist in the use of anti-SOST neutralizing antibodies for the clinical entity of osteoporosis, such as romosozumab (AMG 785; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) [4–6] and blosozumab (LY2541546; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN). Preclinical studies have shown that anti-Sost antibodies inhibit bone loss in ovariectomy [7,8], in the aged skeleton, and during fracture healing [9,10]. The expression and function of SOST in skeletal tumors remain poorly understood.

The importance of avoiding tumorigenesis cannot be overlooked in the field of osteoporotic therapies. This issue has growing importance with protein-based bone anabolism. For example, the main Food and Drug Administration–approved recombinant protein for local bone formation is bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2. BMP ligands and BMP receptors are expressed in most osteosarcoma (OS) cell lines and OS subtypes. Moreover, although disagreement in the literature exists, the presence of BMP signaling in OS may impart a worse prognosis [11]. On the cellular level, BMP signaling appears to mediate promigratory effects in both OS and chondrosarcoma (CS) cell types. Likewise, parathyroid hormone is the main Food and Drug Administration-approved anabolic agent in the treatment of osteoporosis. Unfortunately, the clinical duration of use for parathyroid hormone is limited to 24 months, owing to the potential risk of osteosarcomagenesis (as documented in rat studies) [12]. Thus, currently approved agents for bone anabolism are not without potential risks for skeletal sarcomagenesis.

There is to date little known regarding SOST expression and function in skeletal sarcomas. Several pieces of data suggest that SOST has diverse roles in epithelial malignancies, including breast carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, and renal cell carcinoma. In general, studies have demonstrated that overexpression of numerous Wnt components in OS (including Wnt ligands, Frizzled, and LRP receptors), highlighting the implications of aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling in OS progression [13,14]. In contrast, Wnt antagonists are generally reduced in OS. For example, WIF-1 messenger RNA expression was significantly decreased in numerous OS cell lines in comparison to normal human osteoblasts, attributed to WIF-1 promoter hypermethylation [15]. Investigators found that WIF-1 down-regulates the expression of MMP-9 and 14, thereby preventing the invasion and mobility of OS cells [15]. Kansara et al [16] further confirmed that WIF-1 is epigenetically silenced in human OS, and targeted disruption of WIF-1 accelerates OS formation in mice. Likewise, expression of other Wnt/β-catenin inhibitors, such as FrzB/sFRP3, is consistently suppressed in OS [17]. Conversely, in CS, increased DKK1 expression was recently observed to correlate with high Wnt signaling activity and a poor prognosis [18]. Despite this, the expression and function of SOST in skeletal tumors is poorly understood. Here, we provide a comprehensive description of SOST expression in skeletal bone- and cartilage-forming tumors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies and reagents

Primary antibodies used in this study were anti-SOST (ab75914; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Dako (Carpintería, CA) unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Tissue procurement

Tumors were retrospectively collected from biopsy and resection specimens at the University of California, Los Angeles, under institutional review board number 13–897. Each tumor was re-examined by 2 blinded bone tissue pathologists to ensure accuracy of original diagnosis. When appropriate, radiographs were also examined to confirm concordance with the pathologic diagnosis. Demographic features and specific tumor measurements were recorded, including patient age, sex, anatomical location, tumor size, and history of neoadjuvant therapy (Supplementary Table 1). When available, undecalcified samples were chosen for immunohistochemical staining; 52.8% of samples were decalcified (28/53 samples), including 20 of 36 benign and malignant bone-forming tumors and 8 of 17 benign and malignant cartilage-forming tumors.

2.3. Histologic and immunohistochemical analyses

Five-micrometer-thick paraffin sections of bone and cartilage tumors were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Using H&E sections, histomorphologic assessments were made to confirm tumor type and to determine characteristics of different regions within each section. Additional sections were analyzed by indirect immunohistochemistry. Briefly, unstained sections were deparaffinized in xylene and a series of graded ethanol solutions and rehydrated using phosphate-buffered solution. The slides were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 minutes at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase activity; 0.125% trypsin-induced epitope retrieval was performed for 20 minutes at room temperature, using the “Digest-All 2” system (catalog 00–3008; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Slides were then incubated with the primary antibody for 1 hour at 37°C and 4°C overnight. The anti-SOST primary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:50. After incubation with the primary antibody, slides were incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (Dako) for 1 hour at room temperature, used at 1:200 dilution.

Positive immunoreactivity was detected following ABC complex (PK-6100, Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) incubation and development with AEC chromagen (K346911–2; Dako). Negative controls for each antibody consisted of incubation with secondary antibody in the absence of primary antibody. Sections of nonneoplastic human cortical bone were used in each instance as a positive staining control. Sections were counterstained in Modified Mayer’s Hematoxylin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 30 seconds and placed under running water for 5 minutes. Slides were mounted using aqueous mounting medium (Dako). Photomicrographs were acquired using Olympus BX51 (UPLanFL; Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Intensity and distribution of immunohistochemical stainings were determined by 3 blinded observers. The intensity of staining was estimated using a 3-point scale, with “0” indicating no staining, “1+” indicating predominantly faint/barely perceptible cytoplasmic staining within any percentage of tumor cells, “2+” indicating predominantly weak/moderate cytoplasmic staining within any percentage of tumor cells, and “3+” indicating strong/intense cytoplasmic staining within any percentage of tumor cells. Discrepancies in semiquantification of intensity of staining between observers were found in less than 10% of samples. In this case, the intensity of stain was determined by consensus re-review of the slides by all 3 observers. Distribution of staining was determined on a continuous 0% to 100% scale, estimating the percentage of tumor cells with SOST immunoreactivity in 5% increments.

2.4. Regular polymerase chain reaction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Cells were expanded in standard growth mediums according to cell type, including either (1) DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HOS, MNNG, 143B, KHOS312H, KHOS), (2) RPMI + 10% FBS (SJSA), or (3) McCoy’s medium + 20% FBS (G292). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SOST, Wnt signaling activity, and bone-specific markers was performed upon subconfluency using 6-well culture dishes. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Methods for regular PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were, as previously described, performed in triplicate per RNA isolate [19]. In addition, SOST and osteogenic marker expressions were assayed at serial time points under osteogenic differentiation conditions (0, 3, 6, and 9 days). Osteogenic medium included basal medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid and 3 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate. For RNA expression among primary tumors, samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen as soon as possible after surgical removal. Tissue homogenization and RNA extraction were performed as previously described [19].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using an appropriate Student t test when 2 groups of numerical values were being compared, as in the case of staining distribution. A Fisher exact test was performed to determine statistical significance of contingency tables, as in the case of staining intensity. In general, P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. SOST expression in benign bone tumors

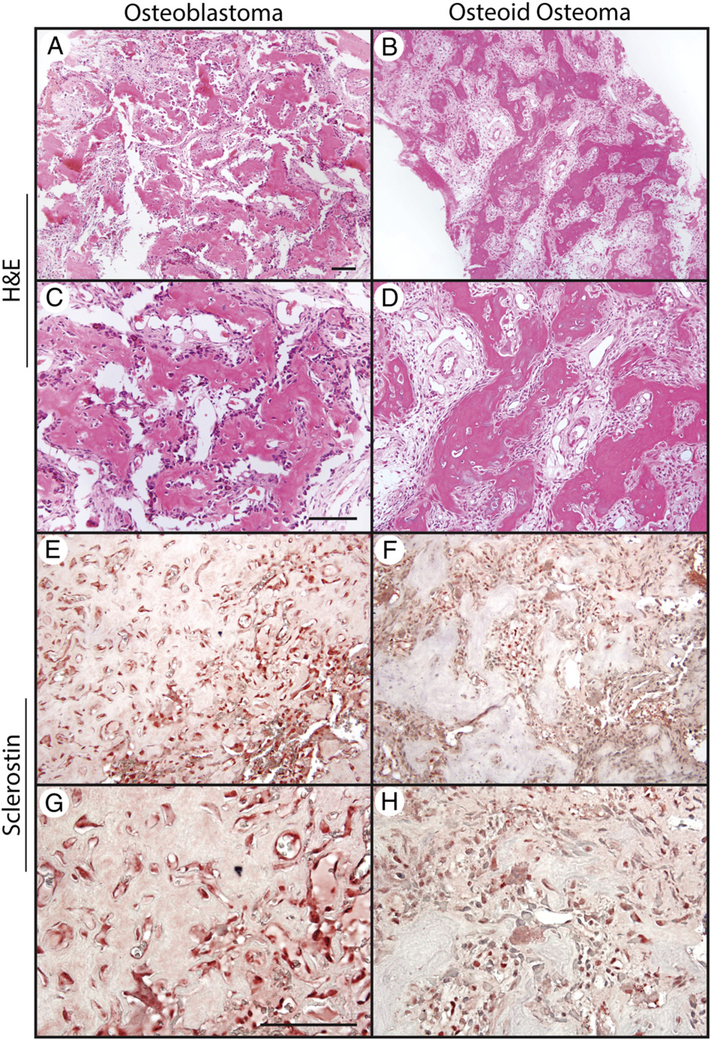

All cases of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma demonstrated characteristic anastomosing trabeculae of woven bone, with a single layer of activated osteoblasts and variable multinucleated osteoclasts (Fig. 1). Weak to intermediate staining intensity for SOST was apparent across all samples. Immunoreactivity was generally in a cytosolic distribution and was observed in a diverse array of cell types within the tumor nidus including, most commonly, bone-lining osteoblasts, bone-entombed osteocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and mononuclear cells within the stroma. Semiquantification of SOST immunore-activity in benign bone-forming tumors demonstrated intermediate to strong intensity of staining in all samples (2+−3+) with the large minority of tumor cells showing immunoreactivity (on average, 47.0% and 48.0% of tumors cells within osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma, respectively) (Table).

Fig. 1.

SOST expression in benign bone-forming tumors. A-D, H&E appearance of osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma. E-H, SOST immunohistochemical staining in osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Table.

Semiquantitative assessment of SOST immunohistochemistry, by tumor subtype

| Tumor type (n) | Staining intensity (% of cases stained) |

Staining distribution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | Mean % of cells stained (±SD) | |

| Osteoid osteoma (5) | – | – | 3/5 (60%) | 2/5 (40%) | 47.0% (±17.2%) |

| Osteoblastoma (5) | – | – | 4/5 (80%) | 1/5 (20%) | 48.0% (±25.9%) |

| Osteosarcoma (41) | 5/41 (12.2%) | 8/41 (19.5%) | 15/41 (36.6%) | 13/41 (31.7%) | 42.4% (±31.0%) |

| Osteoblastic | 4/22 (18%) | 2/22 (9%) | 8/22 (36%) | 8/22 (36%) | 40.4% |

| Chondroblastic | 2/14 (14%) | 2/14 (14%) | 6/14 (43%) | 4/14 (29%) | 33.2% |

| Fibroblastic | – | – | 1/1 (100%) | – | – |

| Giant cell-rich | – | 2/2 (100%) | – | – | – |

| Parosteal | – | 3/7 (43%) | 3/7 (43%) | 1/7 (14%) | 61.0% |

| Periosteal | – | – | 1/1 (100%) | – | – |

| Telangiectatic | 1/5 (20%) | – | 1/5 (20%) | 3/5 (60%) | 26.0% |

| Enchondroma (5) | – | 1/5 (20%) | 4/5 (80%) | – | 21.0% (±16.4%) |

| Chondrosarcoma (12) | – | 2/12 (16.7%) | 7/12 (58.3%) | 3/12 (25.0%) | 50.0% (±27.3%) |

| Grade 1 | – | 1/5 (20%) | 3/5 (60%) | 2/5 (40%) | 61.0% |

| Grade 2 | – | 2/5 (40%) | 3/5 (60%) | – | 35.0% |

| Grade 3 | – | – | 1/2 (50%) | 1/2 (50%) | 55.0% |

3.2. SOST expression in conventional OS

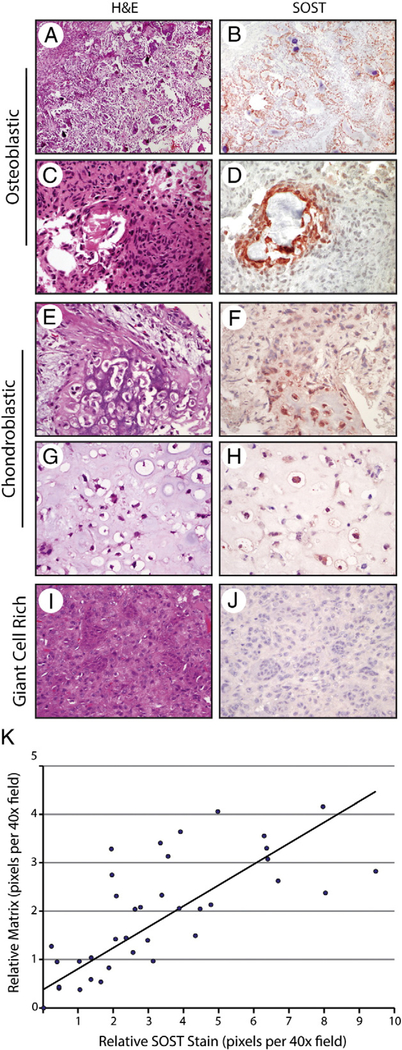

Next, SOST immunoreactivity was examined in osteoblastic OS specimens. Demographic information can be found in Supplementary Table 1. A wide array of tissue types were examined, including initial biopsies, primary resection, and metastatectomy specimens. Of 26 tumors, 12 (46%) were from biopsy or resection samples with no history of chemotherapy or radiation. Results showed that among osteoblastic OS, SOST expression highly correlated with bone matrix expression (Fig. 2A–D). Across samples, we observed high SOST immunoreactivity in those osteoblastic cells lining and immediately adjacent to bone deposition. This was particularly apparent in samples with chemotherapy-induced “differentiation.” Regular PCR confirmed expression of SOST among osteoblastic OS samples on the gene level (Supplementary Fig. 1). Chondroblastic OS samples showed a similar phenomenon with SOST immunoreactivity in and around areas of endochondral ossification (Fig. 2E–H). SOST immunostaining was particularly seen in areas of mineralized cartilage and bone (Fig. 2E and F) but was also in present in areas without mineralization (Fig. 2G and H). Finally, subtypes of conventional OS with minimal bone deposition were examined, including fibroblastic OS and giant cell-rich OS. These subtypes with minimal bone matrix showed infrequent SOST immunoreactive cells (Fig. 2I and J, giant cell-rich OS shown). In these samples with minimal neoplastic bone, sparse SOST expression was present in osteoblastic cells in and around the bone matrix. Semiquantification of SOST immunohistochemical staining was variable and reflected the range of bone production among OS samples (Table). The intensity of staining ranged from weak to strong (1+−3+) with, on average, approximately 42.4% (±31%) of tumor cells demonstrating positive staining (n = 41 specimens). No difference in staining intensity or distribution was seen when comparing OS samples to benign bone-forming tumors (P = .19 and P = .54, respectively). Osteoblastic OS and chondroblastic OS showed a similar pattern of SOST staining, with most showing moderate to strong intensity (2+−3+) in the large minority of tumor cells (40.4% and 33.2% of tumor cells, respectively). Fibroblastic OS and giant cell-rich OS showed focal staining that was weak to moderate in intensity (1–2+). Of note, only viable tumor was considered in semiquantitative grading schemes.

Fig. 2.

SOST expression in conventional OS. A-D, Appearance of H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining in representative osteoblastic OS tumors. E-H, Appearance of H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining in representative chondroblastic OS tumors. I and J, Appearance of H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining in giant cell–rich OS. Scale bar, 100 μm. K, Relative SOST expression as a function of relative bone matrix in conventional OS. Individual random ×40 fields are represented as a single blue dot. The y-axis demonstrates relative bone matrix abundance in comparison to relative SOST immunohistochemical staining on the x-axis. A line of best fit is shown.

To further document the relationship between neoplastic bone matrix and SOST immunohistochemical staining, serial random high-magnification images from conventional OS were quantified both for the degree of SOST staining and amount of bone matrix (Fig. 2K). Briefly, total SOST immunoreactivity per ×40 field and total bone matrix per ×40 field were quantified using Adobe Photoshop, and each high-magnification image was placed on a scatter plot. Results confirmed a significant correlation between relative SOST immunostaining and bone matrix production (correlation coefficient, R2 = 0.6788). In summary, conventional OS showed a reproducible immunohistochemical staining pattern for SOST, with the degree and localization of stain highly correlated with bone matrix production.

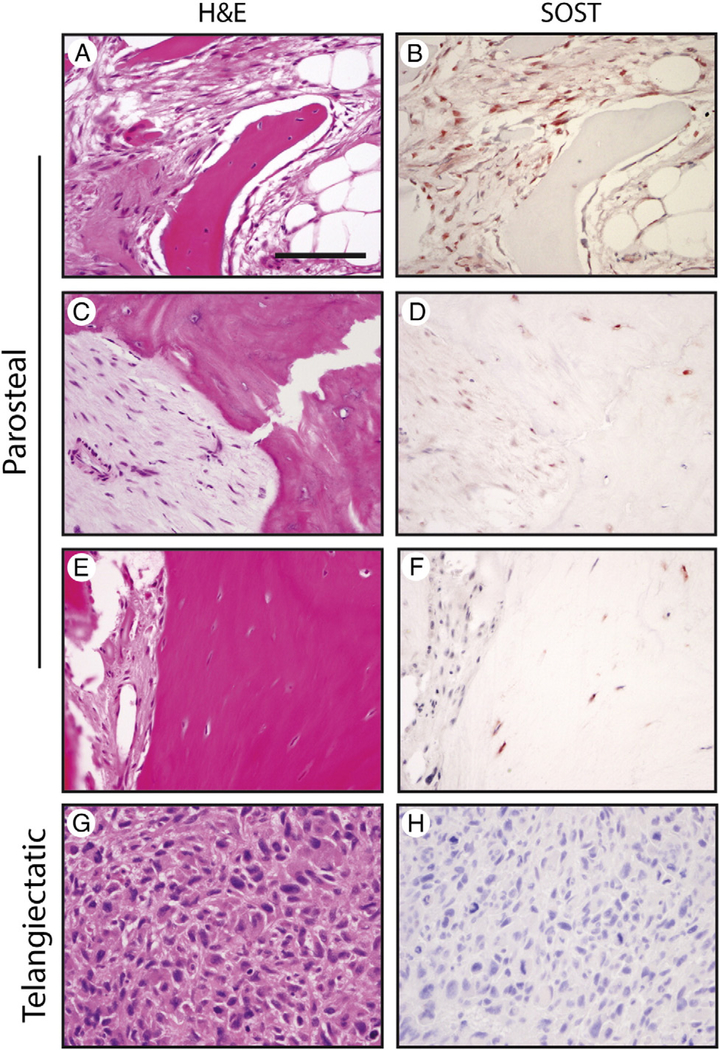

3.3. SOST expression in OS subtypes

We next sought to examine SOST expression among distinct OS subtypes (including parosteal, periosteal, and telangiectatic OS). Examination of parosteal OS specimens revealed a characteristic dual-lineage tumor with alternating zones of bony trabeculae and fibroblastic stroma (Fig. 3A–F). A relative abundance of SOST immunostaining was observed among parosteal OS samples. Staining of variable intensity was observed in a majority of parosteal tumor cells (1+−3+ intensity, 61% of tumor cells). Notably, SOST expression was observed both in the spindle cell population of fibroblastic areas and also within osteocytes of neoplastic bone (Fig. 3A–F). Examination of periosteal OS revealed characteristic featherlike osteoid surrounded by zones of intermediate-grade chondroblastic differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Like conventional OS, SOST immunoreactivity was seen in areas of ossification (2+ staining intensity, not shown). Finally, telangiectatic OS specimens were examined, which demonstrated a characteristic appearance of highly atypical neoplastic cells in a background of blood, fibrin, and sparse bone. Among telangiectatic OS specimens, SOST immunoreactivity was again noted in areas of ossification in the minority of cells (1+−3+, 26% of tumor cells). Tumors without bone deposition showed no detectable SOST expression (Fig. 3G and H). In summary, like conventional OS, most OS variants demonstrate SOST immunoreactivity in and around areas of neoplastic bone. Parosteal OS is the notable exception to this observation, which showed significant SOST expression among both fibrous and osseous components.

Fig. 3.

SOST expression in osteosarcoma variants. Appearance of routine H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining in parosteal OS (A-F) and telangiectatic OS (G and H). Scale bar, 100 μm.

3.4. SOST expression among OS cell lines

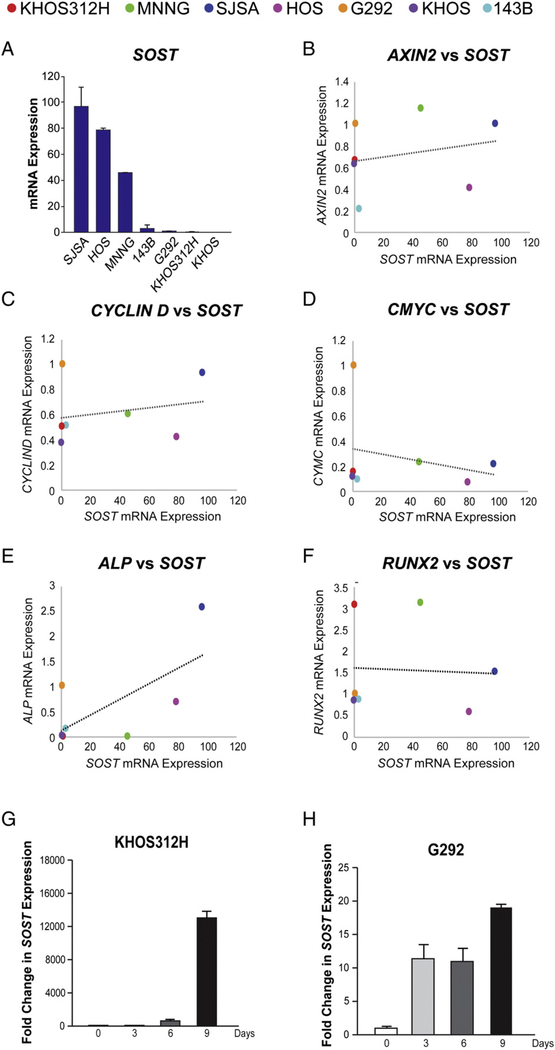

SOST expression was next assayed across OS cell lines (Fig. 4). Results showed a wide variation across OS cell lines (>97-fold variation) (Fig. 4A). Those high-expressing SOST cell lines included SJSA, HOS, and MNNG. Basal SOST expression did not appear to correlate well with known comparative growth rates, cellular morphology, or metastatic potential [20–26].

Fig. 4.

Expression and correlation of SOST expression to gene markers of Wnt signaling activity and osteogenic differentiation across OS cell lines, assessed by qRT-PCR. A, Relative SOST expression across OS cell lines. n = 3 replicates per group. Error bars represent 1 SD. B, Correlation of SOST expression to AXIN2 expression. In scatter plots, each dot represents an OS cell line. The line of best fit is shown. C, Correlation of SOST expression to CYCLIND expression. D, Correlation of SOST expression to CMYC expression. E, Correlation of SOST expression to ALP expression. F, Correlation of SOST expression to RUNX2 expression. n = 3 replicates per group. G and H, Expression of SOST during OS cell osteogenic differentiation, assessed by qRT-PCR. G, Relative SOST expression among KHOS312H cells (days 0–9 of differentiation). H, Relative SOST expression among G292 cells (days 0–9 of differentiation). AH data are normalized to housekeeping gene expression (ACTB).

We next inquired as to whether SOST expression correlated with markers of canonical Wnt signaling or osteogenic differentiation among 7 OS cell lines, as assessed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4B–F). We first inquired as to whether high SOST expression correlated with low Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity, as could be hypothesized from the known functions of SOST as an extracellular Wnt inhibitor (Fig. 4B–D). Markers of Wnt/β-catenin signaling used included AXIN2, CYCLIN D, and CMYC (Fig. 4B–D), with each dot on a scatter plot representing a different OS cell line. Overall, markers of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity did not correlate well with SOST expression. A line of best fit for each gene correlation to SOST is shown (Fig. 4B–D). Correlation coefficients were close to zero for all comparisons (R2 range, 0.04736–0.07395). Next, basal expression of markers of osteogenic differentiation was compared to SOST expression across OS cell lines (Fig. 4E and F). Of the genes assessed, alkaline phosphatase (ALP, a marker of osteoblastic differentiation) expression showed a positive correlation with SOST expression (R2 = 0.46793). In contrast, Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) showed no correlation with SOST expression (R2 = 0.00255). In aggregate, only the marker of osteogenic differentiation ALP showed a correlation with SOST expression among OS cell lines.

Next, we assayed SOST expression during the osteogenic differentiation of OS cell lines (Fig. 4G and H). In general, SOST expression has been reported to increase over time in osteoblastic cell culture. For this purpose, low SOST expressing cell lines (including KHOS312H and G292 lines) were examined under standard osteogenic conditions from 0 to 9 days of differentiation. Results showed a significant and time-dependent induction of SOST expression with osteogenic conditions across both cell lines examined. The absolute change in SOST expression varied widely (overall 19- and 13 045-fold up-regulations for G292 and KHOS312H cells, respectively—a nearly 700-fold difference in absolute change). Next, changes in SOST expression over time under differentiation conditions were compared to the osteogenic markers RUNX2 and OCN (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). For this purpose, relative SOST expression was normalized to either RUNX2 or OCN expression over time in osteogenic culture. Overall, the degree of increase in SOST expression was higher than the degree of increase in either osteogenic marker. This was observed in both KHOS312H and G292 cells (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Overall, SOST expression seemed to correlate with osteogenic gene expression during osteogenic differentiation conditions.

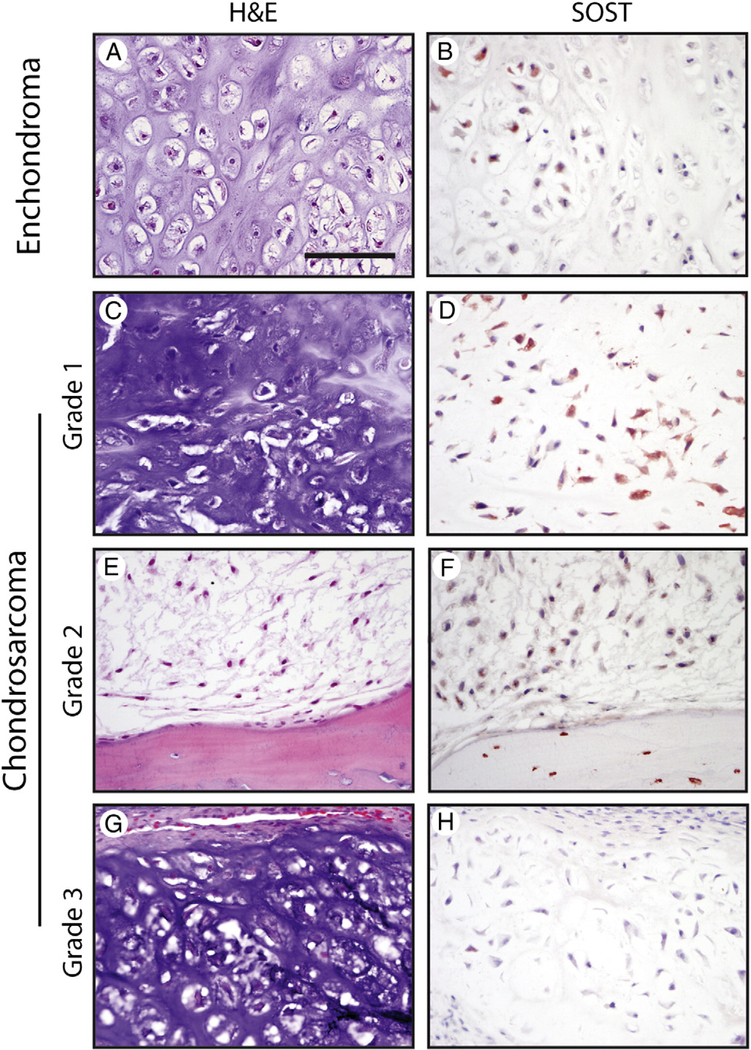

3.5. SOST expression in cartilage-forming tumors

Next, SOST expression was compared across benign and malignant cartilage forming tumors (Fig. 5). All tumors showed some degree of SOST immunoreactivity in the minority of tumor cells (17/17 samples, Table). SOST expression did not necessarily correlate with areas of mineralization or myxoid change in either enchondroma or chondrosarcoma. In enchondroma, SOST immunoreactivity was most often of moderate intensity (2+ in 4/5 tumors) and in the minority of tumor cells (21.0% ± 16.4%). In chondrosarcoma, SOST immunoreactivity was likewise most often of moderate intensity (2+, 58.35% of tumors). Chondrosarcoma cells showed a large and more variable distribution of SOST immunoreactivity than their benign counterparts (50.0% ± 27.3%). In summary, SOST expression is ubiquitous among both benign and malignant tumors with hyaline cartilage. No statistically significant difference in staining intensity or distribution was observed between benign and malignant cartilage-forming tumors (P = .76 and P = .44, respectively).

Fig. 5.

SOST expression in cartilaginous tumors. A and B, Appearance of H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining in enchondroma. C-H, Appearance of H&E staining and SOST immunohistochemical staining among CS tumors, including grade I (C and D), grade II (E and F), and grade III (G and H). Scale bar, 100 μm.

4. Discussion

In brief, the present study has identified several unique features of SOST in skeletal tumors. First, SOST expression is present to some degree across nearly all bone- and cartilage-forming skeletal tumors. Second, the distribution of SOST among OS tumors correlated highly with neoplastic bone deposition, whereas among CS specimens, a correlation with any histopathologic features was not observed. In vitro studies among OS cell lines suggested a positive correlation of SOST with the osteogenic differentiation marker ALP, whereas no significant correlation was observed between SOST expression and markers of Wnt signaling activity.

Our results have similarities and differences to the recently reported expression profiles of SOST by Inagaki et al [27]. Like our study, Inagaki et al described SOST expression across the majority of bone and cartilage tumors, including both benign and malignant tumors. Several findings in our study are in disagreement with their reports, including (1) presence of SOST staining among bone-lining cells of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma, (2) presence of SOST staining in chondroblastic OS, (3) distinctive patterns of SOST expression in parosteal OS in both fibroblastic and osseous components, and (4) SOST staining among all cartilaginous tumors examined (including low- and high-grade chondrosarcoma) that did not necessarily correlate with mineralization. It should be noted that factors such as rarity of tumors, antibody selection, and variable tissue processing may well explain these discrepancies between our 2 studies.

The expression of SOST in OS and CS raises intriguing questions regarding its role in the basic function in skeletal sarcoma tumor biology. The role of other Wnt signaling antagonists has been explored in OS and CS, including WIF-1, SFRP3, and DKK1. In general, numerous Wnt signaling components have been described as up-regulated among OS and CS tumors [13,14,28] (although this is not entirely agreed upon in the literature [29]), whereas Wnt antagonists such as WIF1 and SFRP3 are generally reduced [15–17]. In contrast, DKK1 appears to be up-regulated in OS, both locally and systemically [30]. In CS, DKK1 overexpression when combined with increased Wnt signaling activity portends a worse clinical outcome [18]. Our data clearly localize SOST to OS cells with osteoblastic differentiation. This is not unlike its native expression in osteocytes, and a potential role for SOST in repressing bone formation in OS is a reasonable hypothesis given its distribution. In cartilaginous tumors, the role of SOST is less clear based on its patchy expression pattern, which, in our hands, did not correlate well with areas of mineralization or myxoid change. Importantly, simple detection of SOST inhuman cell lines and human skeletal tumors does not necessarily imply retained bioactivity. It is intriguing, however, to link the overproduction of SOST in OS tumors to the high incidence of osteoporosis among long-term surviving OS patients [31,32]. However, osteoporosis among this patient population is no doubt multifactorial, with contributing factors including exposure to chemotherapeutic agents, poor nutrition, and decreased physical activity. At this point, the potential link between SOST overproduction and osteoporosis among OS patients is a theoretical one.

Several limitations exist for broader extrapolation of the results from the present study. First, we rely on immunohistochemical-based detection of SOST in human tumor samples, which is inherently a descriptive methodology. Moreover, clinical samples vary in their processing, with variable lengths of ischemic time, fixation time, and decalcification time. How these factors influence the SOST antigen is not yet known. Finally, expression profiles within cell lines and primary tumors represent an important step forward in understanding the potential role of SOST in skeletal pathophysiology but are limited by its descriptive nature. Further studies to examine the prognostic importance of SOST expression, as well as the cellular consequences of SOST dysregulation, may shed light on these issues.

5. Concluding remarks

The present study highlights the presence of SOST across benign and malignant bone- and cartilage-forming skeletal tumors. SOST strongly localizes to areas of osteoblastic differentiation and ossification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of UCLA Translational Pathology Core Laboratory, Dr N. Bernthal, and A. S. James for their excellent technical assistance.

Funding/Support: The present work was supported by the UCLA Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the Translational Research Fund, the UCLA Daljit S. and Elaine Sarkaria Fellowship award, the Orthopedic Research and Education Foundation with funding provided by the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases K08 AR06831-01.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2016.07.016.

References

- [1].Martin TJ. Bone biology and anabolic therapies for bone: current status and future prospects. J Bone Metab 2014;21:8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hoeppner LH, Secreto FJ, Westendorf JJ. Wnt signaling as a therapeutic target for bone diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2009;13:485–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li X, Ominsky MS, Niu QT, et al. Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:860–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McClung MR, Grauer A, Boonen S, et al. Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Costa AG, Bilezikian JP, Lewiecki EM. Update on romosozumab: a humanized monoclonal antibody to sclerostin. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014;14:697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Minisola S Romosozumab: from basic to clinical aspects. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014;14:1225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ominsky MS, Niu QT, Li C, et al. Tissue-level mechanisms responsible for the increase in bone formation and bone volume by sclerostin antibody. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:1424–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stolina M, Dwyer D, Niu QT, et al. Temporal changes in systemic and local expression of bone turnover markers during six months of sclerostin antibody administration to ovariectomized rats. Bone 2014;67:305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yao Q, Ni J, Hou Y, et al. Expression of sclerostin scFv and the effect of sclerostin scFv on healing of osteoporotic femur fracture in rats. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014;69:229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alaee F, Virk MS, Tang H, et al. Evaluation of the effects of systemic treatment with a sclerostin neutralizing antibody on bone repair in a rat femoral defect model. J Orthop Res 2014;32:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yoshikawa H, Takaoka K, Masuhara K, et al. Prognostic significance of bone morphogenetic activity in osteosarcoma tissue. Cancer 1988;61: 569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vahle JL, Sato M, Long GG, et al. Skeletal changes in rats given daily subcutaneous injections of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–34) for 2 years and relevance to human safety. Toxicol Pathol 2002;30:312–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen K, Fallen S, Abaan HO, et al. Wnt10b induces chemotaxis of osteosarcoma and correlates with reduced survival. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;51:349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, et al. Expression of LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) as a novel marker for disease progression in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer 2004;109:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rubin EM, Guo Y, Tu K, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 decreases tumorigenesis andmetastasis in osteosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther2010;9:731–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kansara M, Tsang M, Kodjabachian L, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is epigenetically silenced in human osteosarcoma, and targeted disruption accelerates osteosarcomagenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 2009;119:837–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mandal D, Srivastava A, Mahlum E, et al. Severe suppression of Frzb/sFRP3 transcription in osteogenic sarcoma. Gene 2007;386:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen C, Zhou H, Zhang X, et al. Elevated levels of Dickkopf-1 are associated with beta-catenin accumulation and poor prognosis in patients with chondrosarcoma. PLoS One 2014;9:e105414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shen J, James AW, Chung J, et al. NELL-1 promotes cell adhesion and differentiation via Integrinβ1. J Cell Biochem 2012;113:3620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bruserud O, Tronstad KJ, Berge R. In vitro culture of human osteosarcoma cell lines: a comparison of functional characteristics for cell lines cultured in medium without and with fetal calf serum. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2005; 131:377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lauvrak SU, Munthe E, Kresse SH, et al. Functional characterisation of osteosarcoma cell lines and identification of mRNAs and miRNAs associated with aggressive cancer phenotypes. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jian Y, Chen C, Li B, et al. Delocalized Claudin-1 promotes metastasis of human osteosarcoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;466:356–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gorska M, Krzywiec PB, Kuban-Jankowska A, et al. Growth inhibition of osteosarcoma cell lines in 3D cultures: role of nitrosative and oxidative stress. Anticancer Res 2016;36:221–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mu X, Isaac C, Greco N, et al. Notch signaling is associated with ALDH activity and an aggressive metastatic phenotype in murine osteosarcoma cells. Front Oncol 2013;3:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ren L, Mendoza A, Zhu J, et al. Characterization of the metastatic phenotype of a panel of established osteosarcoma cells. Oncotarget 2015;6: 29469–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Endo-Munoz L, Cai N, Cumming A, et al. Progression of osteosarcoma from a non-metastatic to a metastatic phenotype is causally associated with activation of an autocrine and paracrine uPA axis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Inagaki Y, Hookway ES, Kashima TG, et al. Sclerostin expression in bone tumours and tumour-like lesions. Histopathology 2016;69:470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chen C, Zhao M, Tian A, et al. Aberrant activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling drives proliferation of bone sarcoma cells. Oncotarget 2015;6: 17570–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cai Y, Mohseny AB, Karperien M, et al. Inactive Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in conventional high-grade osteosarcoma. J Pathol 2010; 220:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee N, Smolarz AJ, Olson S, et al. A potential role for Dkk-1 in the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma predicts novel diagnostic and treatment strategies. Br J Cancer 2007;97:1552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Holzer G, Krepler P, Koschat MA, et al. Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of highly malignant osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lim JS, Kim DH, Lee JA, et al. Young age at diagnosis, male sex, and decreased lean mass are risk factors of osteoporosis in long-term survivors of osteosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.