Abstract

The assumption of interindividual variability being unimodally distributed in nonlinear mixed effects models does not hold when the population under study displays multimodal parameter distributions. Mixture models allow the identification of parameters characteristic to a subpopulation by describing these multimodalities. Visual predictive check (VPC) is a standard simulation based diagnostic tool, but not yet adapted to account for multimodal parameter distributions. Mixture model analysis provides the probability for an individual to belong to a subpopulation (IPmix) and the most likely subpopulation for an individual to belong to (MIXEST). Using simulated data examples, two implementation strategies were followed to split the data into subpopulations for the development of mixture model specific VPCs. The first strategy splits the observed and simulated data according to the MIXEST assignment. A shortcoming of the MIXEST-based allocation strategy was a biased allocation towards the dominating subpopulation. This shortcoming was avoided by splitting observed and simulated data according to the IPmix assignment. For illustration purpose, the approaches were also applied to an irinotecan mixture model demonstrating 36% lower clearance of irinotecan metabolite (SN-38) in individuals with UGT1A1 homo/heterozygote versus wild-type genotype. VPCs with segregated subpopulations were helpful in identifying model misspecifications which were not evident with standard VPCs. The new tool provides an enhanced power of evaluation of mixture models.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10928-019-09632-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Visual predictive checks, Mixture models, Multimodal parameter distributions, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics

Introduction

Evaluation of the applicability of a model for a specific purpose is a major consideration during pharmacometric analysis. Diagnostic tools have been developed and used extensively for evaluation of pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamics (PD) models [1]. The simulation based diagnostic tool known as visual predictive check (VPC) has gathered much focus because of the (i) advantage to retain the original data profile, (ii) ability to describe the central trend and dispersion in the data, and (iii) simplicity for interpretations [2–5]. A VPC is a graphical and statistical comparison of observed and predicted data by deriving the distribution of observations and predictions against the independent variable such as time [3]. Depending on the underlying data, the objective of the study and the intended use of the model, different VPCs such as stratified VPCs (predictive performance across stratification variable such as a covariate), prediction corrected VPCs (to identify random effect misspecification by removing the variability coming from independent variables such as doses) and covariate VPCs (to evaluate the predictive performance of the model across the covariate range) may be used [3, 4].

The nonlinear mixed effect modeling approach quantifies the intrinsic variability associated with pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles across the studied population [6]. The underlying assumption of interindividual variability (IIV) being unimodally distributed is not true when the studied population exhibits heterogeneity leading to multimodal parameter distributions [7]. Heterogeneous pharmacological behavior may result in clinically significant differences in drug exposure/toxicity. A classic example involves acetylation polymorphism in case of isoniazid where clearance (CL) was observed to be bimodally distributed and a higher prevalence of peripheral neuropathy and hepatotoxicity was observed in slow metabolizers due to elevated plasma concentrations [8]. Situations may arise where a polymorphism is associated with the exposure/response to a drug, but the covariate capable of describing such behavior is not available. The mixture modeling (also referred as clustering) approach is a useful tool under such circumstances [9]. A number of studies have been reported to utilize mixture modeling. A major proportion of these studies aimed to describe the bimodal distribution of CL as reported in case of serotonin receptor antagonist repinotan, antianginal drug perhexiline and beta-lactam antibiotic ceftizoxime [10–12]. A bivariate absorption describing the subpopulations with and without absorption lag was presented by Piotrovsky et al. [13]. An analysis was performed to segregate the patients with and without adverse effects with the help of adverse event data by Kowalski et al. [14]. Mixture modeling was also applied to model the probability of cure in cancer survival analysis where the proportion of fatal and cured cases was estimated [15–17]. Similarly, a mixture model classifying the mammary tumors in rats as benign or malignant was published by Spilker et al. [18].

Despite the utility of mixture models to describe data arising from a population with underlying heterogeneity, there are limitations in assessing mixture models since the common simulation based assessment tools do not account for the multimodality in parameter distributions. Attempts have been made to develop posterior predictive checks [19] for mixture models [8]. However, VPCs are not yet adapted to mixture models and may fail to adequately evaluate the predictive performance of a mixture model. The aim of the current project was to design VPCs accounting for multimodal parameter distributions and thereby allow (i) the diagnosis of the mixture component aspects of the model, and (ii) more powerful assessment of other model aspects by reducing between-subpopulation variability from the graphs.

Methods

Theoretical overview of parameter estimation using mixture models

The underlying assumption behind the mixture modeling approach is to partition the population into subpopulations according to a probability model [8]. With the implementation of mixture models using the $MIXTURE subroutine in NONMEM, pharmacokinetic parameters characteristic to a subpopulation can be obtained [20].

Whereas, the corresponding subpopulation probabilities are estimated as,

A Pmix1 estimate of 0.6 corresponds to a 60/40% mixture proportion. The individual likelihood to belong to a subpopulation 1 (ILmix1) can be derived from the individual objective function value (IOFV). The individual probability for belonging to a subpopulation (IPmix) is then computed from the individual likelihood (ILmix) and population probability estimates [7].

where ILmix2 is the corresponding likelihood estimate for the individual to belong to subpopulation 2. The empirical subpopulation assignment that the subject’s data is described by the corresponding submodel is given the name MIXEST within NONMEM.

Mixture model output

Analysis with mixture models provided two individual-level metrics of subpopulation association (i) the most likely subpopulation for an individual to belong to, and (ii) the probability for an individual to belong to each subpopulation [7]. The former metric (MIXEST) is discrete in nature and can be retrieved from output table files. The latter metric termed IPmix can be retrieved from the *.phm file which is a standard output of models with mixture components. IPmix is considered to be more informative than the MIXEST variable because of its continuous nature.

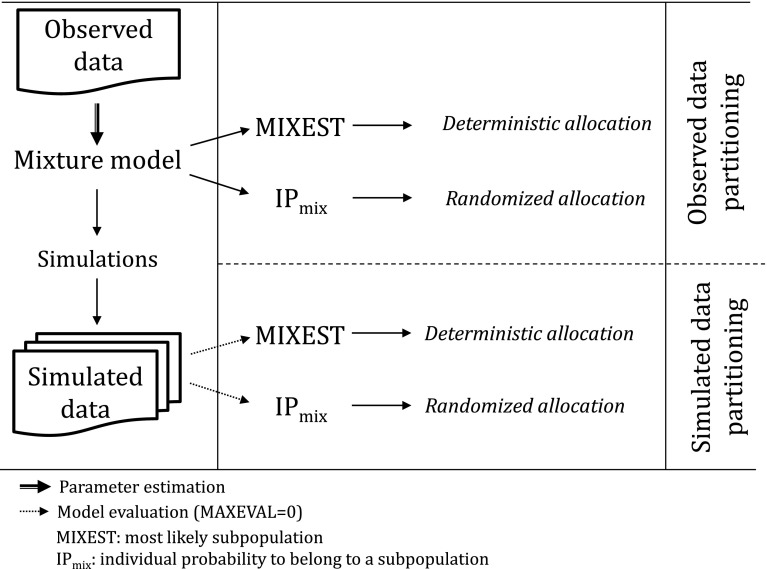

Mixture specific VPCs

Two strategies were adapted for allocation of subjects to the subpopulations in order to develop mixture model specific VPCs with separate panels for each allocated subpopulation. The first strategy utilized the MIXEST information to stratify the observed and simulated data. Thus, the original and simulated individuals were separated according to their most likely subpopulation. A tendency for subjects to be allocated to the dominating subpopulation (similar to the shrinkage phenomenon in individual, empirical Bayes, parameter estimation) is expected with the MIXEST-based allocation strategy. This shortcoming was avoided through the second strategy to randomly partition the observed and simulated data according to the IPmix value. Partitioning with the former approach was called MIXEST mixture while the latter was termed randomized mixture. In order to retrieve the IPmix information for the original and simulated data, an evaluation step is required. This was accomplished by directing NONMEM to perform an evaluation step given the final model parameters by setting MAXEVAL = 0 for each simulated data set. Naturally, MIXEST can also be computed from the IPmix value, therefore further processing to derive VPC statistics for graphical display was facilitated by the use of single output file (*.phm). A discrepancy in the individual subpopulation allocation frequency between original and simulated data would be indicative of model misspecification and hence provide an additional evaluation aspect specific for mixture models. Therefore, percentage of individuals in each subpopulation for both the original (ORIGID) and the simulated data (SIMID) and the population estimate for the mixture probability (PMIX) are displayed in the VPC plots.

Implementation of mixture VPCs

A PsN functionality was developed to direct NONMEM runs and post-processing NONMEM output according to the two strategies (MIXEST and randomized) in order to generate the mixture model VPCs. VPCs were implemented using a ggplot2 based package in R [21–23].

Linear PK data

Data was simulated from a one-compartment PK model (ka = 1 h−1, CL = 20/80 L/h, Vd = 100 L; interindividual variances = 0.09; proportional residual variance = 0.04). A total of 1000 virtual subjects were simulated with 70/30% mixture proportions. Six samples were taken at time points 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 h following a virtual dose of 100 mg. A bivariate covariate resulting in a fourfold difference in CL between subgroups was modeled by the inclusion of a mixture component. In order to compare the mixture model with a model without any mixture component stochastic simulation and estimation (SSE) was performed with PsN version 4.8.0 [24]. The simulated data were analyzed by fitting a covariate-free non-mixture model, a covariate model and a mixture model using NONMEM version 7.4.2 [20]. VPCs were constructed for the mixture model using both the MIXEST and the randomized allocation. Performance of the allocation strategies was evaluated by decreasing the difference in drug CL (20/60 L/h) and increasing size of the dominant subpopulation (85/15% mixture proportions).

Parallel linear and nonlinear PK data

Pharmacokinetic data and NONMEM code were extracted from a publically available illustrative PK model example [25]. Thirty-six subjects were part of the analysis with a rich sampling over a period of 672 h (22 observations per individual). Individuals received 4 doses of 50 mg at 0, 168, 336 and 504 h. The pharmacokinetic profile was described by a two-compartment model with two distinct physiological elimination pathways (linear and nonlinear). The pharmacokinetic parameters included Vmax = 1.2 mg/h, Km = 10 mg/L, CLlinear = 0.03/0.12 L/h, V1 = 3 L, V2 = 2 L and Q = 0.075 L/h. The parameters for drug disposition (CLlinear, Vmax, V1 and V2) were scaled with the body weight of each individual. A bivariate covariate describing a fourfolds difference in the linear CL pathway with a 40/60% mixture proportions was introduced before simulation. SSE was performed to simulate the data given the model parameters followed by estimation with a mixture model. Mixture specific VPCs were developed to assess the predictive performance of the model.

Irinotecan PK data

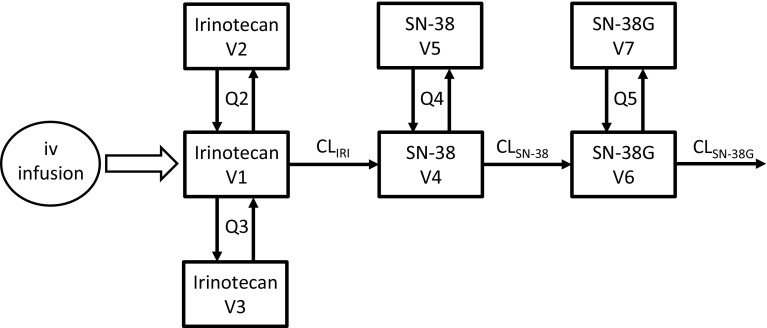

Irinotecan PK profile was described by a combined model from previously published studies [26, 27]. Data comprised of 109 patients with various malignant solid tumors who received an intravenous infusion of 100–350 mg/m2 for a period of 0.75–2.25 h. A total number of 1930 plasma concentration measurements of active metabolite SN-38 were available for the analysis. The model (Fig. 5) comprised of a three-compartment model for the parent drug, a two-compartment model for the active metabolite (SN-38) and a two-compartment model for the inactive glucuronide conjugate of SN-38 (SN-38G). The drug was characterized by linear PK properties and the disposition parameters were scaled with body surface area. IIV was associated with all the parameters and the residual unexplained variability was modeled by an additive model. Based on the established influence of genetic polymorphism upon SN-38 CL, a mixture model was developed as the patient genotype information was unavailable. Traditional and mixture specific VPCs were developed for the irinotecan mixture model for comparative evaluation of the recently developed methodology.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the irinotecan mixture model having 36% lower CL of SN-38 in patients with UGT1A1 hetero/homozygote versus wild-type genotype

Results

Allocation of individuals to subpopulations according to MIXEST and IPmix information is elaborated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of proposed methodology

VPCs for linear PK data

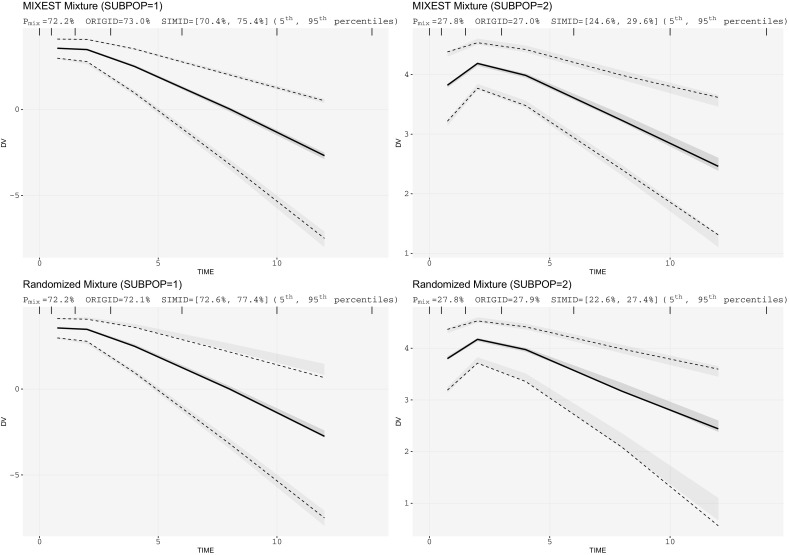

SSE results showed that the mixture model with a Pmix estimate of 72.2% provided an improved goodness-of-fit (OFV = − 664) over the covariate free, non-mixture model (OFV = − 642). The inclusion of covariate information provided the best fit (OFV = − 774), as expected. Figure 2 presents the mixture specific VPCs for the simulated PK data with linear kinetics. Both the MIXEST and the randomized mixtures were adequate to evaluate the predictive performance of the model. However, for a population with a comparatively lower difference in drug CL (20/60 L/h) and a greater proportion of dominant subpopulation (Pmix estimate of 85.8%) an allocation bias towards the dominant subpopulation was observed with the MIXEST based method (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Mixture VPCs for linear PK data: upper panel displays MIXEST based VPCs while lower panel displays IPmix based VPCs. One-compartment mixture model with 70/30% mixture proportions having fourfolds CL difference. (SUBPOP subpopulation number, Pmix estimated population proportion, ORIGID, SIMID individuals (%) allocated to respective subpopulations in original and simulated data respectively)

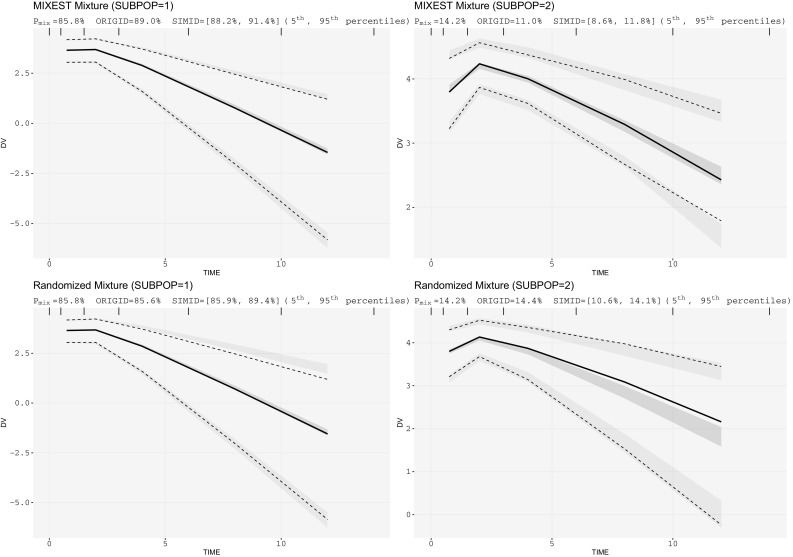

Fig. 3.

Mixture VPCs for parallel linear and nonlinear PK data: one-compartment mixture model with 85/15% mixture proportions having threefolds CL difference

VPCs for parallel linear and nonlinear PK data

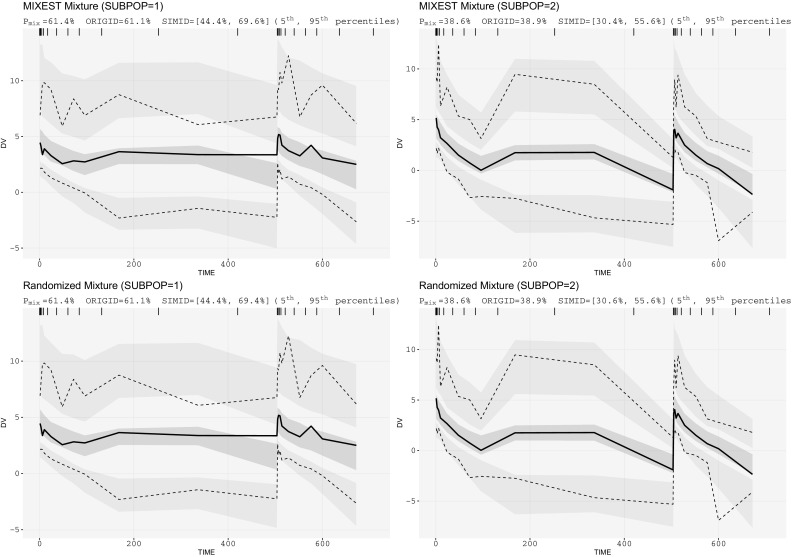

Mixture VPCs for a mixture model describing parallel linear and nonlinear CL pathways are presented in Fig. 4. Pmix was estimated to 61.4%. No allocation bias was observed in this case as the fourfolds difference in CL for the linear pathway was sufficient to separate the subpopulations with 40/60% proportions.

Fig. 4.

Mixture VPCs for irinotecan PK data: two-compartment model with mixed elimination kinetics having a mixture proportion of 60/40% with fourfolds CL difference (mixture component on linear CL model)

VPCs for irinotecan PK data

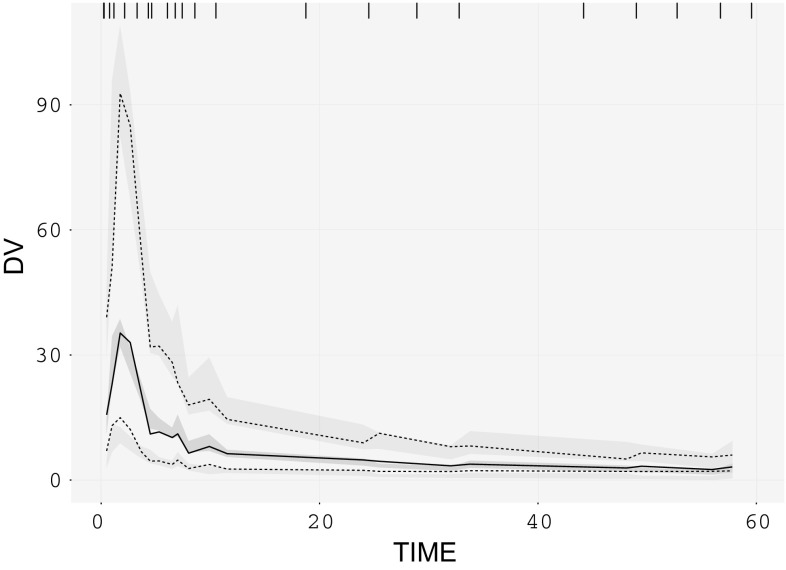

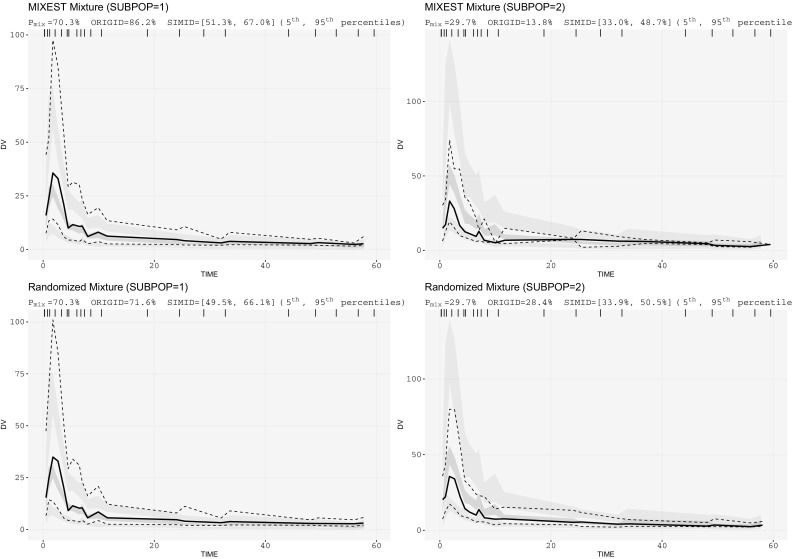

The irinotecan mixture model (Fig. 5) provided a Pmix estimate of 70.3% and an approximately 36% lower CL of SN-38 in patients with UGT1A1 hetero/homozygote (*1/*28, *28/*28) versus wild-type (*1/*1) genotype. The traditional VPC (Fig. 6) did not show any model misspecification implying that the model was adequate to describe the pharmacokinetics of the population under study. However, a model misspecification was captured with the implementation of recent approaches. It was evident from mixture VPCs (Fig. 7) that the mixture model was under-predictive for slow metabolizers while over-predictive for fast metabolizers.

Fig. 6.

Traditional VPC for irinotecan mixture model

Fig. 7.

Mixture VPCs for irinotecan mixture model; left panel: VPCs for slow metabolizers; right panel: VPCs for fast metabolizers

Discussion

A major objective during population analysis is to identify, or otherwise manage, the sources of variability in order to assist decision making. Sources for variability characterized in PK/PD models result in predictable differences in exposure/responses between patient groups and provide a tool to tailor the treatment individually. Identifying not only the magnitude, but also the shape of the unexplained variability can be important. Mixture models are suitable for appropriately characterizing multimodality associated with parameter distributions. VPC is considered to be one of the most informative tools, able to simultaneously diagnose the fixed and random effects [3, 4]. Therefore, mixture VPCs were designed to overcome the limitations of the classical VPCs for the evaluation of mixture models.

Evaluation with the two VPC implementation strategies for simulated data (Fig. 2) illustrates how mixture VPCs can be useful to split the data into subpopulations thereby enhancing the power of evaluation by decreasing the remaining variability within a subpopulation. Both the MIXEST and the IPmix based allocation strategies were adequate to cluster the simulated data for a drug exhibiting linear PK with sufficiently differentiable CL (20/80 L/h). Apart from the visual evaluation, information provided in the display is of significant importance. The population probability estimate (Pmix) is representative of the agreement of the model with prevalence of subpopulations in existing literature. Uncertainty or bias associated with Pmix can be reflective of model misspecification or insufficient information available in the data. The number of individuals allocated to the respective subgroups should be in accordance with the Pmix estimate. Allocation bias in the original and the simulated data can be evaluated from the values assigned to ORIGID and SIMID. No discrepancy between MIXEST and IPmix based allocation of individuals in this illustrative example implies that the data was informative enough to separate the individuals according to their likelihood/probability estimates.

As multimodal parameter distributions stem from a failure to incorporate a multimodally distributed covariate in the model, it is good practice to consider existing covariate data before the decision to proceed with mixture models. Model comparison using SSE results confirm that the covariate model provides a preference over the mixture model, while a mixture model in turn is a better characterization of the data compared to the standard, unimodal distribution.

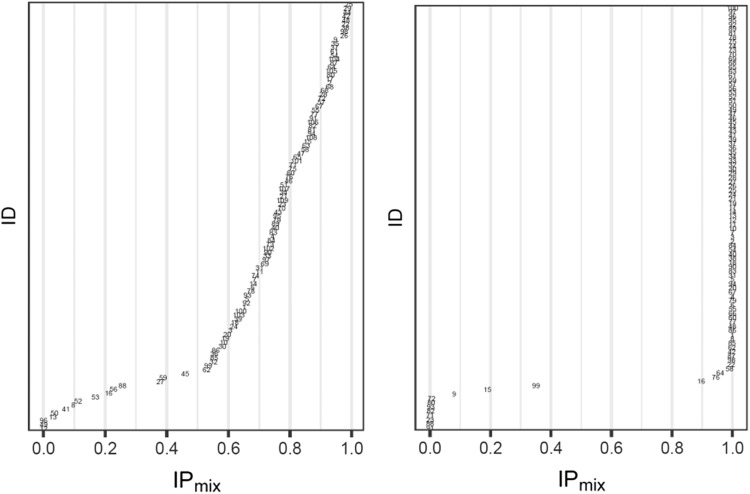

Under circumstances where the individual data is less informative, the MIXEST estimate may exhibit shrinkage towards the dominant subpopulation in contrast to IPmix. Kaila et al. [28] used Monte Carlo simulations to examine factors that might impact the ability to correctly classify a subject in a bimodal group. Using a one-compartment model with subjects assigned to one of two CL groups, the authors found that misclassification of individuals was dependent on (i) the magnitude of the difference between the mean CL estimates for the subgroups, (ii) IIV in CL, (iii) proportion of subjects in each subpopulation and (iv) sample size. One should be careful to inspect multimodalities in all the parameter estimates and not only the parameter of physiological interest. A probability partitioning may exist across more than one parameter. There may be a 30/70% partitioning for CL, but a 10/90% partitioning for the volume of distribution. Analysis of such data with a model containing a single mixture component may also lead to uncertainty in probability estimates leading to misclassification or biased allocation. Figure 3 demonstrates a biased allocation where the fraction of the dominant subpopulation was larger (85/15%) and the difference in CL was comparatively lower (20/60 L/h). An allocation bias of 3.2% towards the larger subpopulation can be observed with the MIXEST mixture. The less informative individuals with IPmix estimate around 0.5 can be identified with the help of a diagnostic plot displaying the distribution of individuals in a mixture (Fig. 8). The plot presents a less separated (left) and a clearly separated (right) mixture population. We hereby demonstrate that a randomized allocation based upon IPmix information takes into account the uncertainty for an individual to belong to a subpopulation where the data from an individual is less informative.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of individuals in a population; left panel: a less separated mixture; right panel: a clearly separated mixture

Figure 4 displays VPCs for a population with mixed elimination kinetics. The phenomenon is often observed for therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. The linear CL pathway is possibly mediated by antibody Fc-receptors interaction, while the nonlinear CL pathway reflects binding to its pharmacologic target. A higher allocation bias (16%) using MIXEST method was observed with the evaluation of irinotecan mixture model. Moreover, a clear model misspecification was observable from mixture VPCs (Fig. 7) which was otherwise not evident from the classical VPC (Fig. 6). Irinotecan mixture VPCs were supportive of the argument that by reducing the between subpopulation variability in the VPC an enhanced power of evaluation can be achieved. Mixture VPCs were suggestive of further structural model modifications to adequately describe the subpopulation profiles but the respective analysis was beyond the scope of current project.

VPCs like other simulation-based diagnostics test a model’s ability to generate data that mimics the observed data. Systematic differences between simulated and real data indicate the deficiency of the model to predict the observed data. An important aspect regarding such procedures is that post-processing of both the observed and simulated data is done in similar way, regardless of whether the post-processing occurs through model-based or model-independent methods. Indeed, model-based post-processing can be advantageous to learn about the model misspecifications [29, 30]. Capturing misspecification in a feature of the model does not necessarily mean that the model is inadequate for its purpose. Such decisions are contextual in nature. Although, a considerable number of cases can be seen where mixture modeling approach was used to report results [31–40], but the class of mixture models did not gather much attention to develop diagnostics. Recommended diagnostics for the assessment of non-linear mixed effects models such as VPC, conditional weighted residuals (CWRES), normalized prediction distribution errors (NPDE) are relatively new [1] and less applicable to mixture models. A recent procedure was presented by Lavielle et al. [41] but does not address mixture models either. Implementation of recent methodology would assist both model developers and users to better assess the mixture aspects than what is being practiced currently.

The proposed methodologies are implemented in PsN and VPCs can be generated with the addition of the option

−mix

to the vpc command. For comparative evaluation purpose, a traditional VPC plot was also included in the PsN output.

Conclusions

A graphical and statistical comparison of observations and predictions derived from the multimodal distributions in mixture models is presented. Partitioning of observed and predicted data between subpopulations can be done in two ways depending on the underlying information (MIXEST or IPmix). Randomized allocation based upon individual IPmix information provides a preference over MIXEST based discrete allocation as a lower allocation bias is associated with the former case. Mixture VPCs can be a useful diagnostic tool for the development and evaluation of mixture models in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a scholarship grant to Mr. Usman Arshad from the Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan in collaboration with the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). We acknowledge Prof. Dr. Uwe Fuhr, University of Cologne, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Cologne, Center for Pharmacology, Department I of Pharmacology, Cologne, Germany for his encouragement and support during the course of study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nguyen THT, Mouksassi M-S, Holford N, et al. Model evaluation of continuous data pharmacometric models: metrics and graphics. CPT: Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6:87–109. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holford N (2005) The visual predictive check—superiority to standard diagnostic (Rorschach) plots. PAGE 14. Abstr 738. www.page-meeting.org/?abstract=738. Accessed 8 Jan 2018

- 3.Karlsson MO, Holford N (2008) A tutorial on visual predictive checks. PAGE 17. Abstr 1434. http://www.page-meeting.org/?abstract=1434. Accessed 15 Jan 2018

- 4.Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13:143–151. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamsen KM, Patel K, Nieforth K, Kirkpatrick CMJ. A regression approach to visual predictive checks for population pharmacometric models. CPT: Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2018;7:678–686. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development. CPT Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2012;1:1–14. doi: 10.1038/psp.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlsson KC, Savic RM, Hooker AC, Karlsson MO. Modeling subpopulations with the $mixture subroutine in NONMEM: finding the individual probability of belonging to a subpopulation for the use in model analysis and improved decision making. AAPS J. 2009;11:148–154. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peretti E, Karlaganis G, Lauterburg GH. Acetylation of acetylhydrazine, the toxic metabolite of isoniazid in humans. Inhibition by concomitant administration of isoniazid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:686–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frame B. Mixture modeling in NONMEM V. In: Ette EI, Williams PJ, editors. Pharmacometrics: the science of quantitative pharmacology. Hoboken: Willey; 2007. pp. 723–757. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanigawa T, Heinig R, Kuroki Y, Higuchi S. Evaluation of interethnic differences in repinotan pharmacokinetics by using population approach. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2006;21:61–69. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.21.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein R, Charles BG, Morris RG, Rasiah RL. Population pharmacokinetics of perhexiline from very sparse, routine monitoring data. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23:636–643. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facca B, Frame B, Triesenberg S. Population pharmacokinetics of ceftizoxime administered by continuous infusion in clinically ill adult patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1783–1787. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piotrovsky V, Van Peer A, Van Osselaer N, Armstrong M, Aerssens J. Galantamine population pharmacokinetics in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: modeling and simulations. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:514–523. doi: 10.1177/0091270003251853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowalski KG, McFadyen L, Hutmacher MM, Frame B, Miller R. A two-part mixture model for longitudinal adverse event severity data. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2003;30:315–336. doi: 10.1023/B:JOPA.0000008157.26321.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Hakulinen T, Soderman B, Verdecchia A. Mixture models for cancer survival analysis: application to population based data with covariates. Stat Med. 1999;18:441–454. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990228)18:4<441::AID-SIM23>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips N, Coldman A, McBride ML. Estimating cancer prevalence using mixture models for cancer survival. Stat Med. 2002;21:1257–1270. doi: 10.1002/sim.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon NH. Cure mixture models in breast cancer survival studies. In: Jewell NP, Kimber AC, Lee MLT, Whitmore GA, editors. Lifetime data: models in reliability and survival analysis. Boston: Springer; 1996. pp. 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spilker ME, Seng AKY, Yao A, et al. Mixture model approach to tumor classification based on pharmacokinetic measures of tumor permeability. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:549–558. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano Y, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. Evaluating pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics models using the posterior predicitive check. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2001;28:171–192. doi: 10.1023/A:1011555016423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beal S, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann A, Bauer RJ. NONMEM user’s guides (1989-2009) Ellicott City: Icon Development Solutions; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Cham: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keizer R (2017) vpc: R package version 1.0.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vpc. Accessed 10 Jan 2018

- 23.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 17 Dec 2017

- 24.Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN. PsN-Toolkit—a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;79:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gastonguay M. Metrum Research Group. https://metrumrg.com/course/mi212-advanced-topics-population-pk-pd-modeling-simulation. Accessed 14 May 2018

- 26.Xie R, Mathijssen RH, Sparreboom A, Verweij J, Karlsson MO. Clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan and its metabolites in relation with diarrhea. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:265–275. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.126741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiménez BJ, Ruixo JJP. Influencia de los polimorfismos genéticos en UGT1A1, UGT1A7 y UGT1A9 sobre la farmacocinética de irinotecán, SN-38 y SN-38G. Farm Hosp. 2013;37:111–127. doi: 10.7399/FH.2013.37.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaila N, Straka RJ, Brundage RC. Mixture models and subpopulation classification: a pharmacokinetic simulation study and application to metoprolol CYP2D6 phenotype. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2006;34:141–156. doi: 10.1007/s10928-006-9038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brendel K, Comets E, Laffont C, Laveille C, Mentré F. Metrics for external model evaluation with an application to the population pharmacokinetics of gliclazide. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2036–2049. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim MMA, Nordgren R, Kjellsson MC, Karlsson MO. Model-based residual post-processing for residual model identification. AAPS J. 2018;20:81. doi: 10.1208/s12248-018-0240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamaki Y, Maema K, Kakara M, Fukae M, Kinoshita R, Kashihara Y, Muraki S, Hirota T, Ieiri I. Characterization of changes in HbA1c in patients with and without secondary failure after metformin treatments by a population pharmacodynamic analysis using mixture models. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2018;33:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoemaker R, Wade JR, Stockis A. Brivaracetam population pharmacokinetics and exposure-response modeling in adult subjects with partial-onset seizures. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:1591–1602. doi: 10.1002/jcph.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woloch C, Di Paolo A, Marouani H, Bocci G, Ciccolini J, Lacarelle B, Danesi R, Iliadis A. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of 5-FU and 5-FDHU in colorectal cancer patients: search for biomarkers associated with gastro-intestinal toxicity. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12:1713–1719. doi: 10.2174/156802612803531414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woillard JB, de Winter BC, Kamar N, Marquet P, Rostaing L, Rousseau A. Population pharmacokinetic model and Bayesian estimator for two tacrolimus formulations–twice daily Prograf and once daily Advagraf. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohy Das JP, Kyaw MP, Nyunt MH, Chit K, Aye KH, Aye MM, Karlsson MO, Bergstrand M, Tarning J. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of artesunate in patients with artemisinin sensitive and resistant infections in Southern Myanmar. Malar J. 2018;17:126. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2278-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schalkwijk S, Ter Heine R, Colbers AC, et al. A mechanism-based population pharmacokinetic analysis assessing the feasibility of efavirenz dose reduction to 400 mg in pregnant women. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57:1421–1433. doi: 10.1007/s40262-018-0642-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Francis J, Zvada SP, Denti P et al (2018) AADAC gene polymorphism and HIV infection affect the exposure of rifapentine: a population pharmacokinetics analysis. PAGE 27. Abstr 8695. www.page-meeting.org/?abstract=8695. Accessed 25 Dec 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Bienczak A, Cook A, Wiesner L, et al. Effect of diurnal variation, CYP2B6 genotype and age on the pharmacokinetics of nevirapine in African children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;72:190–199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polepally AR, Pennell PB, Brundage RC, et al. Model-based lamotrigine clearance changes during pregnancy: clinical implication. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1:99–106. doi: 10.1002/acn3.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkins JJ, Langdon G, McIlleron H, Pillai G, Smith PJ, Simonsson US. Variability in the population pharmacokinetics of isoniazid in South African tuberculosis patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03940.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavielle M, Ribba B. Enhanced method for diagnosing pharmacometric models: random sampling from conditional distributions. Pharm Res. 2016;33:2979. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-2020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.