Abstract

The coexistence of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the neocortex is linked to neural system failure and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. However, the underlying neuronal mechanisms are unknown. By employing in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging of layer 2/3 cortical neurons in mice expressing human Aβ and tau, we reveal a dramatic tau-dependent suppression of activity and silencing of many neurons, which dominates over Aβ-dependent neuronal hyperactivity. We show that neurofibrillary tangles are neither sufficient nor required for the silencing, which instead is dependent on soluble tau. Surprisingly, although rapidly effective in tau mice, suppression of tau gene expression was much less effective in rescuing neuronal impairments in mice containing both Aβ and tau. Together, our results reveal how Aβ and tau synergize to impair the functional integrity of neural circuits in vivo and suggest a possible cellular explanation contributing to disappointing results from anti-Aβ therapeutic trials.

The primary pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are extracellular plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)1. The main component of plaques is the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, while NFTs are composed mainly of the protein tau. Autopsy and recent positron emission tomography studies revealed that the formation of plaques is spatially and temporally separated from that of NFTs: plaques first form in the neocortex and spread inward to deeper brain regions, while NFTs first form in limbic areas, from where they spread outward to the neocortex2–4. Several lines of evidence suggest that the propagation of tau pathology into the Aβ plaque-bearing cortex is linked to the transition from the preclinical (asymptomatic) to the clinical (symptomatic) stage of Alzheimer’s disease5–7. While previous studies have shown that the interaction between Aβ and tau causes enhanced pathology6–14, the functional consequences for intact neuronal circuits remain unknown. To address this question, we employed in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging of large populations of neurons in layer 2/3 of the neocortex in novel Alzheimer’s disease model mice that display spatially overlapping Aβ and tau pathologies in the cortex, similar to Alzheimer’s disease patients.

Results

Aβ promotes neuronal hyperactivity while tau suppresses activity

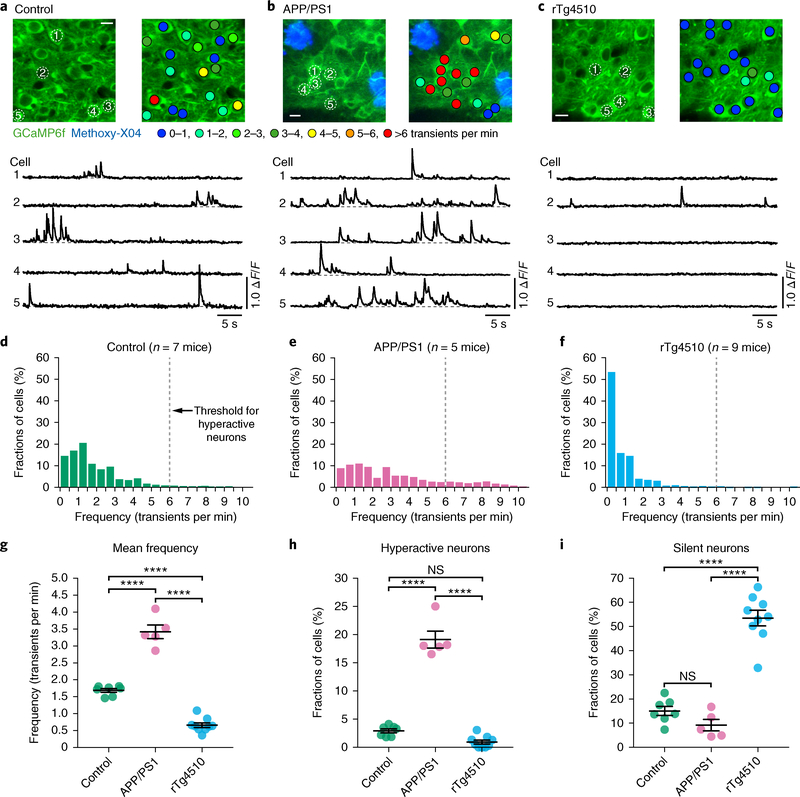

We began by monitoring action potential-related spontaneous Ca2+ transients15,16 in GCaMP6f-expressing cortical layer 2/3 neurons of APPswe:PS1ΔE9 (henceforth APP/PS1) transgenic mice that overexpress human Aβ and develop only Aβ plaques, but no cytosolic tau pathology. APP/PS1 mice and all other mice used in this study are on the same FVBB6F1 genetic background (see Methods and Life Sciences Reporting Summary for details regarding the breeding strategy). In agreement with previous results17–20, we detected hyperactivity of layer 2/3 neurons in 6–12-month-old plaque-bearing APP/PS1 mice (mean age 8.4 months; see also Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2a for details regarding age distributions and the rationale for pooling functional neuronal data from mice at this 6–12-month age range) when compared to their wild-type controls (mean age 8.4 months; Fig. 1a–h). We then analyzed layer 2/3 neuronal activity in age-matched rTg4510 transgenic mice that express aggregating human tauP301L and display NFTs but no Aβ pathology (Fig. 1c). In stark contrast to the results obtained with APP/PS1 mice, in all nine rTg4510 mice (mean age 8.4 months) examined, there was a strong reduction of cortical activity levels (Fig. 1c–h; linear mixed effects model (LMEM) for log rates on genetic background, F(2,4351) = 132, P = 1.2 × 10−56; all post hoc comparisons between genotypes (controls, APP/PS1, rTg4510) were highly significant, P < 10−6). Detailed analysis of all recorded neurons revealed that, relative to controls and APP/PS1 mice, there was a 3.6-fold and 5.8-fold increase in the proportion of silent neurons in the rTg4510 mice (Fig. 1i), but virtually no neuronal hyperactivity (Fig. 1h). We then analyzed immunohistochemically stained brain sections from the imaged rTg4510 mice and found that NFTs were present only in 1.21% of GCaMP6f-expressing cells (18 out of 1,483 cells were double-positive for Alz50/Paired-helical filament 1 (PHF1) and green fluorescent protein (GFP); Supplementary Fig. 3), leading us to the hypothesis that tau aggregation is not necessary for neuronal silencing.

Fig. 1 |. Neuronal hyperactivity in APP/PS1 mice but silencing in rTg4510 tau mice.

a-c, Top, in vivo two-photon fluorescence images of GCaMP6f-expressing (green) layer 2/3 neurons in the parietal cortex and corresponding activity maps from wild-type controls (a), APP/PS1 (b), and rTg4510 (c) mice. In APP/PS1 mice, plaques were labeled with methoxy-X04 (blue); in the activity maps, neurons were color-coded as a function of their mean activity. Scale bars, 10 μm. Bottom, spontaneous Ca2+ transients of neurons indicated in the top panel. d-f, Frequency distributions of all recorded neurons in controls (d; green, n = 1,705 neurons in 7 mice), APP/PS1 (e; magenta, n = 878 neurons in 5 mice), and rTg4510 mice (f; light blue, n = 1,771 neurons in 9 mice). The dashed line at 6 transients per min indicates the threshold used to identify hyperactive neurons; silent neurons exhibit 0 transients per min. g, Mean neuronal frequencies for controls (1.69 ± 0.05 transients per min), APP/PS1 (3.42 ± 0.20 transients per min), and rTg4510 (0.66 ± 0.07 transients per min); F(2,18) = 171.2, P = 1.93 × 10−12. All post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were highly significant: P = 5.42 × 10−9 for controls vs. APP/ PS1, P = 1.38 × 10−6 for controls vs. rTg4510, and P = 1.01 × 10−12 for APP/PS1 vs. rTg4510. h, Fractions of hyperactive neurons. Controls: 2.91 ± 0.35%, APP/PS1: 19.11 ± 1.50%, rTg4510: 0.93 ± 0.35%; F(2,18) = 176.2, P = 1.51 × 10−12. Post hoc multiple comparisons were P = 2.84 × 10−11 for controls vs. APP/PS1, P = 1.64 × 10−12 for APP/PS1 vs. rTg4510 and not significant, P = 0.1045, for controls vs. rTg4510. i, Fractions of silent neurons. Controls: 15.05 ± 1.87%, APP/PS1: 9.20 ± 2.36%, rTg4510: 53.48±3.24%; F(2,18) = 77.18, P = 1.48 × 10−9. Post hoc multiple comparisons were P = 2.02 × 10−8 for controls vs. rTg4510 and P = 1.08 × 10−8 for APP/PS1 vs. rTg4510 and not significant, P = 0.3972, for controls vs.s APP/PS1. Each solid circle represents an individual animal (controls, n = 7; APP/PS1, n = 5; rTg4510, n = 9) and all error bars reflect the mean ± s.e.m; the differences between genotypes were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ****P < 0.0001. NS, not significant.

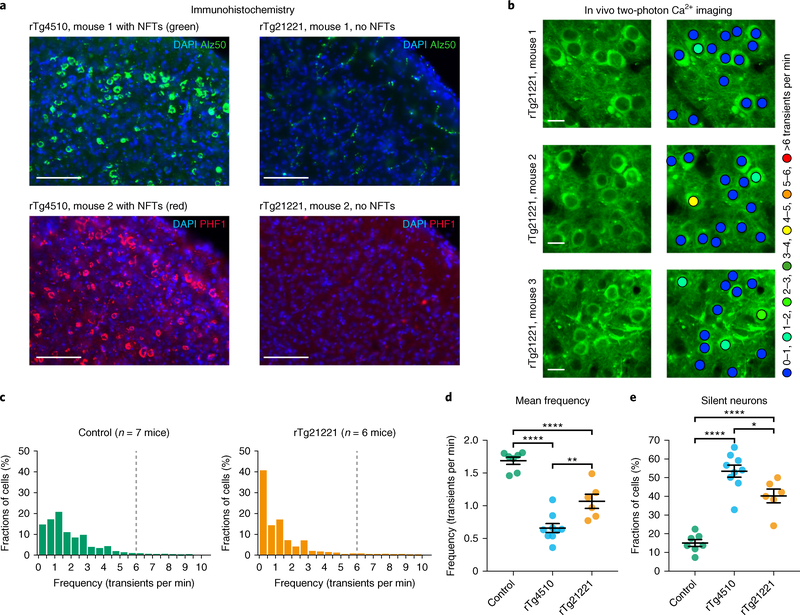

To test this hypothesis directly, we performed recordings in rTg21221 mice that overproduce non-aggregating wild-type human tau at comparable levels as rTg4510 mice but lack NFTs (Fig. 2a, right panel, and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Indeed, Fig. 2b–e shows that, similar to rTg4510 mice (Fig. 1), in 6–12-month-old rTg21221 mice (n = 6; mean age 8.9 months) there was a marked reduction of layer 2/3 neuronal activity levels (LMEM for log rates on genetic background, F(2,4494) = 183, P = 1.6 × 10−77; post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were P < 0.0001), as well as a strong increase in the fractions of silent neurons (Fig. 2e). These results indicate that the impairment of neurons can occur independently of tau aggregation and NFT formation.

Fig. 2 |. NFTs are not required for neuronal silencing.

a, Coronal sections showing many Alz50-positive (top, green) and PHF1-positive (bottom, red) NFTs in the cortex of rTg4510 mice (n = 4 mice, 8–10 sections per mouse were analyzed), but not in rTg21221 mice (n = 4 mice, 5–12 sections per mouse were analyzed). Nuclei are visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm. b, In vivo two-photon fluorescence images of GCaMP6f-expressing (green) layer 2/3 neurons and corresponding activity maps from three example rTg21221 mice illustrating the marked silencing of many neurons. Scale bars, 10 μm. c, Frequency distributions of all recorded neurons in wild-type controls (left panel, green, n = 1,705 neurons in 7 mice) and rTg21221 mice (right panel, orange, n = 1,021 neurons in 6 mice). d, Mean frequency of silent neurons. Controls: 1.69 ± 0.05 transients per min; rTg4510: 0.66 ± 0.07 transients per min; rTg21221: 1.07 ± 0.11 transients per min. F(2,19) = 48.43, P = 3.47 × 10−8. All post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were significant: P = 2.01 × 10−8 for controls vs. rTg4510, P = 1.00 × 10−4 for controls vs. rTg21221, P = 0.0038 for rTg4510 vs. rTg21221. e, Fractions of silent neurons. Controls: 15.05 ± 1.87%; rTg4510: 53.48 ± 3.24%; rTg21221: 40.25 ± 3.64%. F(2,19) = 42.94, P = 8.94 × 10−8. All post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were significant: P = 5.55 × 10−8 for controls vs. rTg4510, P = 7.85 × 10−5 for controls vs. rTg21221, P = 0.0179 for rTg4510 vs. rTg21221. The data for the controls and rTg4510 mice are the same as in Fig. 1. Each solid circle represents an individual animal and all error bars reflect the mean ± s.e.m; the differences between genotypes were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

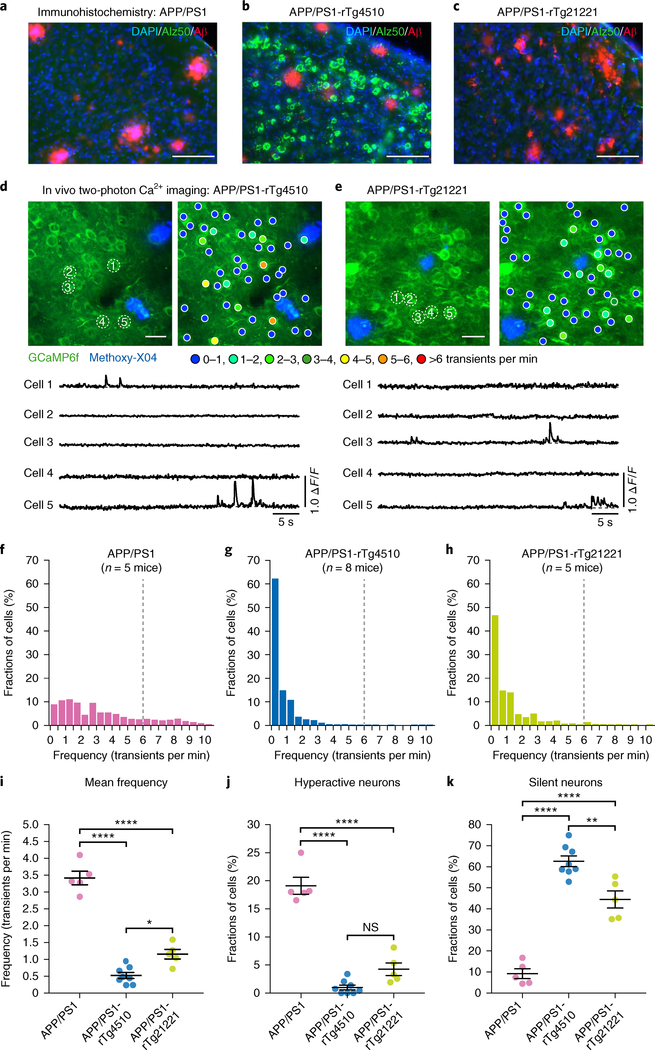

Combination of Aβ and tau leads to suppressed activity

Having demonstrated that Aβ and tau alone have markedly opposite effects on the activity status of neurons, we next asked what is the net effect of Aβ and tau together. To address this question, we performed recordings in 6–12-month-old APP/PS1 mice crossed with rTg4510 or rTg21221 mice11,21 (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 6). To our surprise, neuronal hyperactivity was not only completely abolished in the resulting APP/PS1-rTg4510 (n = 8; mean age 7.6 months) and APP/PS1-rTg21221 (n = 5; mean age 7.9 months) mice, but there was also a strong reduction in cortical activity levels (Fig. 3d–j; LMEM for log rates on genetic background, F(3,5558) = 671, P = 0; post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were all P < 2 × 10−20). Further analysis revealed that, similar to rTg4510 and rTg21221 mice, abnormally silent neurons constitute a large pool of layer 2/3 neurons both in APP/PS1-rTg4510 and APP/PS1-rTg21221 mice (Fig. 3k). We independently obtained similar results in a 17–24-month-old cohort of mice (mean age 20.6 months; Supplementary Fig. 7; see also Supplementary Figs. 2b and 8 for more details on age distributions and the rationale for pooling neuronal data from mice at this 17–24-month age range).

Fig. 3 |. No hyperactivity and many silent neurons in mice harboring both tau and Aβ.

a-c, Coronal sections showing the coexistence of NFTs (green) and Aβ plaques (red) in the cortex of APP/PS1-rTg4510 mice (b), but only plaques in APP/PS1 (a) and APP/PS1-rTg21221 (c) mice. Immunostaining was repeated independently in multiple animals (APP/PS1, n = 7; APP/PS1-rTg4510, n = 15; APP/PS1-rTg21221, n = 13) with similar results. Scale bars, 100 μm. d,e, Top: in vivo two-photon fluorescence images of layer 2/3 neurons and corresponding activity maps from APP/PS1-rTg4510 (d) and APP/PS1-rTg21221 (e) mice. Methoxy-X04-labeled plaques are shown in blue. Bottom: spontaneous Ca2+ transients of neurons indicated in the top panel. Scale bars, 20 μm. f-h, Frequency distribution of all recorded neurons in APP/PS1 (f, n = 878 neurons in 5 mice), APP/PS1-rTg4510 (g, n = 2,092 neurons in 8 mice) and APP/PS1-rTg21221 mice (h, n = 1,050 neurons in 5 mice). i, Summary graph representing the mean frequencies. APP/PS1: 3.42 ± 0.20 transients per min; APP/PS1-rTg4510: 0.52 ± 0.09 transients per min; APP/PS1-rTg21221: 1.16 ± 0.14 transients per min. F(2,15) = 119.9, P = 5.96 × 10−10. All post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were significant: P = 4.36 × 1 0−10 for APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg4510; P = 5.64 × 10−8 for APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221; P = 0.012 for APP/PS1-rTg4510 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221. j, Fractions of hyperactive neurons. APP/PS1: 19.11 ± 1.50%; APP/PS1-rTg4510: 1.00 ± 0.43%; APP/PS1-rTg21221: 4.25 ± 1.13%. F(2,15) = 98.35, P = 2.39 × 10−9. Post hoc multiple comparisons were highly significant: P = 2.02 × 10−9 for APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg4510 as well as APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221 (P = 1.21 × 10−7), but not significant (P = 0.065) for APP/PS1-rTg4510 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221. k, Fractions of silent neurons. APP/PS1: 9.20 ± 2.36%; APP/PS1-rTg4510: 62.61 ± 2.56%; APP/PS1-rTg21221: 44.47 ± 4.10%. F(2,15) = 80.86, P = 9.25 × 10−9. All post hoc multiple comparisons between genotypes were significant: P = 5.72 × 10−9 for APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg4510; P = 4.87 × 10−6 for APP/PS1 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221; and P = 0.002 for APP/PS1-rTg4510 vs. APP/PS1-rTg21221. Data for APP/PS1 mice are the same as shown in Fig. 1. Each solid circle represents an individual animal and all error bars reflect the mean ± s.e.m; the differences among genotypes were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. NS, not significant.

Given that the rTg4510 transgene is associated with an age-dependent loss of neurons, which is enhanced in the APP/PS1-rTg4510 crosses11, potentially contributing to the observed functional impairments, we next analyzed young, 3–4-month-old rTg4510 mice with and without the APP/PS1 transgene. This analysis revealed a strong reduction in neuronal activities (significant effect of group: F(3,5594) = 14.9, P = 1.1 × 10−9; post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between the APP/PS1-rTg4510 and all other groups) and increased fractions of silent layer 2/3 neurons in the APP/PS1-rTg4510 crosses already at this early disease stage, before overt neuropathology and neurodegeneration (Supplementary Fig. 9). Supplementary Fig. 10 shows a comparison of the age-dependent changes of cortical neuronal activities for all genotypes. Together, these results indicate that tau blocks Aβ-dependent hyperactivity, resulting in a profound silencing of circuits when both Aβ and tau are present together in the cortex, and they reinforce the idea that NFTs are not critical for this suppression of neuronal activity.

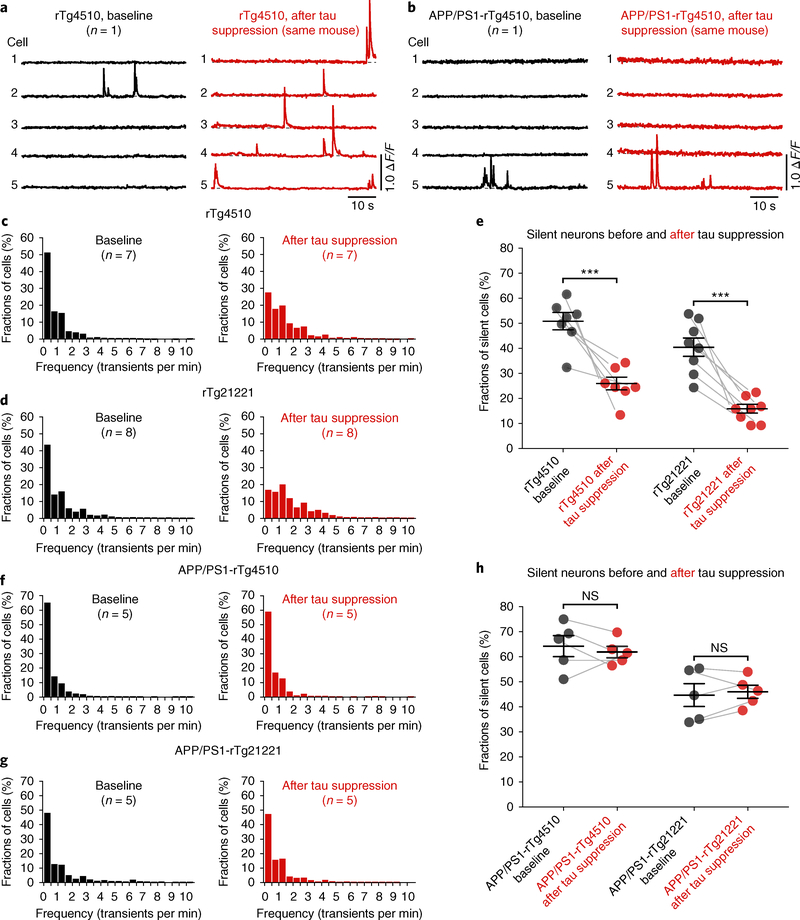

In the presence of Aβ, tau reduction is less effective in rescuing neuronal impairments

Finally, we employed repeated two-photon Ca2+ imaging and determined, in the same mice, whether impaired neuronal circuit function could be rescued by suppressing tau transgene expression. In these experiments, we took advantage of the fact that the tau mice used in this study were equipped with a regulatable promoter system, which allowed us to turn off the expression of the tau transgene by administering a doxycycline (DOX)-containing diet, as demonstrated in several previous studies22–24. We carried out two-photon Ca2+ imaging of layer 2/3 neurons in the same mice before and six weeks after DOX treatment (all mice were at least six months of age when DOX treatment was started). We found that the neuronal impairments were apparently completely reversed in rTg21221 (n = 8) and rTg4510 (n = 7) mice (Fig. 4a–e; Supplementary Fig. 11), despite the continued presence of cortical NFTs (Supplementary Fig. 12a–c). However, instead of the expected rescue of circuit impairment, in all five recorded APP/PS1-rTg4510 and all five recorded APP/PS1-rTg21221 mice there was no apparent change in the fractions of silent neurons after DOX treatment (Fig. 4b–h; Supplementary Fig. 11). The activity levels (Fig. 4c,d,f,g) showed a significant interaction between crossing with APP/PS1 and DOX treatment for both rTg4510 and rTg21221 mice (LMEM for log rates on APP/PS1 crossing and DOX treatment, rTg4510: interaction F(1,4615) = 49.0, P = 2.8 × 10−12; post hoc, DOX treatment increased significantly (P < 0.05) the activity level for both crossed and uncrossed strains, but the increase in activity levels for the crossed strain was significantly smaller—compare with Fig. 4c,f; rTg21221: interaction F(1,3170) = 94, P = 6.1 × 10−22; post hoc, DOX treatment significantly increased activity levels in the uncrossed, but not in the crossed, strain—compare with Fig. 4d,g). Importantly, the observation that tau suppression in the presence of Aβ was significantly less effective in restoring normal neuronal activities could not be explained by the degree of tau reduction, because enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis showed significant and comparable reductions of total human tau levels on DOX treatment in all genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 12d–g). In line with previous reports22, we also found that sarkosyl-soluble tau levels, measured in forebrain homogenates of rTg4510 mice with and without the APP/ PS1 transgene using western blot, were reduced by DOX treatment, while sarkosyl-insoluble fractions were not significantly affected (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Fig. 4 |. Tau transgene suppression rescues neuronal silencing in tau mice but not in mice with tau and Aβ.

a,b, Example activity traces from neurons before (black) and after (red) tau suppression with DOX in the same rTg4510 (a) and APP/PS1-rTg4510 (b) mice. c,d, Frequency distributions of all recorded neurons from rTg4510 mice (c) before (baseline, n = 1,412 neurons in 7 mice) and after (n = 1,118 neurons in same 7 mice) DOX. The same is shown for rTg21221 mice (d) (before DOX, n = 1,675 neurons in 8 mice; after DOX, n = 1,036 neurons in same 8 mice). e, Fractions of silent neurons in rTg4510 (left; n = 7 mice) and rTg21221 (right; n = 8 mice) before and after DOX (rTg4510 before DOX, 50.84 ± 3.49% vs. after DOX, 25.92 ± 2.57%, t = 5.753, d.f. = 11.03, P = 1.26 × 10−4; rTg21221 before DOX, 40.45 ± 3.68% vs. after DOX, 15.87 ± 1.74%, t = 6.047, d.f. = 9.972, P = 1.26 × 10−4). f, Frequency distributions from APP/PS1-rTg4510 mice before (n = 1,262 neurons in 5 mice) and after (n = 827 neurons in same 5 mice) DOX. g, The same is shown for APP/PS1-rTg21221 mice (before DOX, n = 795 neurons in 5 mice; after DOX, n = 904 neurons in the same 5 mice). h, Fractions of silent neurons in APP/PS1-rTg4510 (left; n = 5 mice) and APP/PS1-rTg21221 (right; n = 5 mice) before and after DOX. APP/PS1-rTg4510 before DOX, 64.25 ± 4.21% vs. after DOX, 61.87 ± 2.28%, t = 0.4962, d.f. = 6.152, P = 0.6370. APP/PS1-rTg21221 before DOX, 44.72 ± 4.59% versus after DOX, 46.04 ± 2.64%, t = 0.2494, d.f. = 6.387, P = 0.8109. Each solid circle represents an individual animal and the error bars represent the mean ± s.e.m.; the differences among groups were assessed using two-sided Welch’s t tests, ***P < 0.001. NS, not significant.

To determine if tau suppression would be effective in mice harboring tau and Aβ at an earlier age, before substantial neuropathology and neurodegeneration, we treated 3–4-month-old rTg4510 mice with and without the APP/PS1 transgene with DOX for six weeks. Supplementary Fig. 14 shows that, while there was a significant reduction in the fractions of silent neurons in rTg4510 mice (significant effect of treatment, F(1,1388) = 28.1, P = 1.3 × 10−7), in APP/PS1-rTg4510 crosses the fractions of silent neurons remained unchanged (no significant effect of treatment, F(1,3195) = 0.47, P = 0.49). To show that the effects differed in the rTg4510 mice with and without the APP/PS1 transgene, we performed a LMEM. As expected, there were main effects of APP/PS1 crossing (F(1,4583) = 37.1, P = 1.2 × 10−9) and of DOX treatment (F(1,4583) = 29.0, P = 7.4 × 10−8); importantly, the interaction was significant (F(1,4583) = 21.9, P = 2.9 × 10−6), demonstrating that the difference between the effects of DOX treatment in the young rTg4510 and APP/PS1-rTg4510 mice were highly significant. Again, ELISA analysis showed a substantial reduction in total human tau levels in all mice receiving DOX (Supplementary Fig. 14e,f). As a control, we treated wild-type control mice with DOX and found no significant effects (Supplementary Fig. 15; F(1,2686) = 0.589, P = 0.44).

Discussion

Our study reveals that the two major proteins involved in Alzheimer’s disease have dramatically opposing effects on the activity of neuronal circuits in vivo. Aβ alone causes hyperactivity, whereas tau alone suppresses activity and promotes silencing of many neurons. Remarkably, neuronal silencing dominates over hyperactivity when Aβ and tau are present together, which is corroborated by a recent in vitro study employing extracellular field recordings in entorhinal cortex slices25. However, the dramatic dominance of tau was unexpected in light of previous studies suggesting that tau regulates, and is essential for, Aβ-dependent hyperexcitability26–28. While the effects of transgene insertion must always be considered, the Aβ-induced hyperactivity phenotype is observed in multiple amyloid precursor protein (APP)-overexpressing lines with different transgene arrays29 and is blocked by β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme (BACE) inhibitors, which presumably impact primarily Aβ generation20; the tau phenotype is observed in two different tau transgenic lines that express two different tau transgenes (tauP301L or wild-type) with substantially different age-related histopathological phenotypes (aggregated tau and NFTs and neurodegeneration in rTg4510, or not in the rTg21221 line). Taken together with the observation that DOX suppression of the transgene ameliorates the abnormal physiology, we believe that the most parsimonious explanation for these observations is that Aβ and tau are responsible for the hyperactivity and suppressed baseline excitability observed in our study.

Our results fit well with and provide a possible cellular explanation for the clinical observations that (1) Alzheimer’s disease patients exhibit a progressive decrease of whole-brain activity30–32 and regional cerebral blood flow33 as well as a slowing of the electroencephalogram34, and that (2) tau, rather than Aβ, determines cognitive status7,35,36. The dominance of tau could also explain the relative lack of clinical improvement after Aβ suppression in recent clinical trials. In this context, it is noteworthy that Alzheimer’s disease carries an increased risk of epileptic seizures37, and that several studies have shown increased activation of brain regions, such as the hippocampus, using blood oxygenation level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging38,39 (but see Khan et al.40). To reconcile these observations with our results, it is important to better understand the precise relationship between single-neuron and (abnormal) population activity. Nonetheless, as neuronal hyperactivity appears to be more related to Aβ29, it is possible that epileptiform activity and blood oxygenation level-dependent hyperactivation are more prominent in Alzheimer’s disease patients who have relatively higher Aβ than tau levels, that is, at very early (possibly presymptomatic) points in the disease process when Aβ deposits occur throughout the cortex, but NFTs are limited to the medial temporal lobe. This appears to be the case for hyperactivity in the hippocampus diagnosed with functional magnetic resonance imaging38. Our finding that tau suppresses neuronal activity agrees with previous electrophysiological studies41–43 and goes on to demonstrate that soluble, non-aggregated tau is sufficient for neuronal silencing, and that NFTs are not required. The link between soluble tau and neuronal dysfunction may provide a mechanistic explanation for the observation that, in mouse models, cognitive deficits occur independently of NFT formation22,44–48; that NFTs are not necessarily associated with functional impairments is also in line with previous studies showing that NFT-bearing cortical neurons can reliably respond to strong synaptic inputs, for example, during simple sensory stimuli49,50. Another unexpected but intriguing result of our study was the finding that suppression of tau gene expression rescued neuronal circuit impairments in tau mice, but was significantly less effective when Aβ was present at the same time. This lack of effect was present already in young mice, before substantial neuropathology, synapse loss, and neuro degeneration; nonetheless, it may be related to more severe and persisting synaptic and cellular changes in the context of (soluble) Aβ-tau interactions compared to Aβ or tau alone. Notably, aggregated tau in NFTs is the target for several ongoing clinical trials; our current data argue that readouts for these trials also need to be reconsidered. Together, our results clarify the pathological role of interaction between Aβ and tau in impairing neuronal circuit integrity and function in Alzheimer’s disease, with important mechanistic and therapeutic implications not only for Alzheimer’s disease, but also for other tauopathies and conditions that are associated with elevated tau.

Methods

Animals

The generation, care, and use of animals as well as all experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Massachusetts General Hospital and McLaughlin Research Institute for Biomedical Sciences. All mice were housed in standard mouse cages on wood bedding under conventional laboratory conditions (12-h dark and 12-h light cycle, constant temperature and humidity); they were given food and water ad libitum. Male and female mice were used in the study and randomly allocated to the experiments. B6.Cg-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9)85Dbo/MmJ mice (henceforth designated APP/PS1) were initially obtained from The Jackson Laboratory51. APP/PS1 mice were crossed with the B6.Cg-Tg(Camk2a-tTA)1/Mmay tet transactivator strain that expresses tetracycline-controlled transactivator protein (tTA) from the CK-tTA transgene exclusively in the forebrain52. Double transgenic B6.CK-tTA, APP/PS1 males were selected as sires for the experimental cross with dams from the tetracycline-responsive element strain FVB-Tg(tetO-MAPT*P301L)4510/Kha/Jlws (henceforth Tg4510) or FVB-Tg(tetO-MAPT*wt)21221 (henceforth Tg21221) to produce APP/PS1-rTg4510 or APP/PS1-rTg21221 mice with the experimental, tau-expressing genotypes plus mice negative for either the responder or transactivator transgene that do not express any human tau. All of the same sex offspring of these crosses share the FVBB6F1 background and are genetically identical to one another except for the transgene arrays that they carry.

Surgery and injection of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator

Mice were initially anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in O2 and maintained on 2% isoflurane during the surgical procedure. The body temperature of the anesthetized mice was maintained at ~37.5 °C using a heating pad; ophthalmic ointment was applied to protect the eyes. Using aseptic techniques, the skin above the skull was removed and, by using a fine-tipped dental drill, two craniotomies were performed over the left and right parietal cortices. Then, the fast and ultrasensitive genetically encoded fluorescent Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6f16 (AAV1.Syn.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40; purchased from University of Pennsylvania Vector Core), was stereotactically (Kopf Instruments) injected into layer 2/3 (~300 μm deep) at a rate of 0.2 μl min−1 using a Pump 11 Elite microsyringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). A single injection (~1 μl of viral construct) was made in each cortical hemisphere. A round glass coverslip (8 mm diameter) was placed over both craniotomies and sealed to the bone using a mix of dental cement and cyanoacrylate50. After surgery, mice were returned to their home cage for 2–3 weeks. Analgesia (buprenorphine and acetaminophen) was continued for 3 d postoperatively.

In vivo two-photon fluorescence microscopy

To minimize brain state-dependent experimental variables53 and for better comparison with previous studies17–20, in the present study imaging was performed under light isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in O2 for induction; a reduced concentration of isoflurane (~1%) was used during the imaging. After induction, we waited at least 60 min before imaging. The animal’s body temperature was maintained at ~37.5 °C with a heating pad; ophthalmic ointment was applied to protect the eyes. Two-photon imaging was performed on a Fluoview FV1000MPE multiphoton microscope (Olympus) equipped with a mode-locked MaiTai Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics) tuned to 900 nm. Spontaneous Ca2+ fluorescence signals from cortical layer 2/3 were recorded at ~15 Hz through a 25×, 1.05 numerical aperture water immersion objective (6× digital zoom; Olympus). Scanning and image acquisition was controlled by the Fluoview software (Olympus). Imaging was carried out across multiple fields of view (256 × 256 pixels, 84.41 × 84.41 μm) per mouse, and each field of view was recorded for at least 130 s. Image analysis was performed offline using the Fiji package of ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and Igor Pro (WaveMetrics). First, regions of interest were drawn around individual neuronal somata; then, relative GCaMP6f fluorescence change versus time traces were generated for each region of interest. Ca2+ transients were identified as changes in relative fluorescence that were three times larger than the s.d. of the baseline fluorescence. Based on previous protocols19,20, neurons were classified according to their individual activity rates as silent (0 transients per min), normal (0–6 transients per min), or hyperactive (≥6 transients per min).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain hemispheres from mice were drop fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 48 h at 4 °C. After fixation, brains were washed with PBS, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose, and sliced into 40-μm-thick coronal sections with a sliding microtome (SM2000 R; Leica). Sections were rinsed three times in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in TBS for 20 min. Sections were then blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in TBS for 60 min at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C in primary antibodies diluted in 5% NGS. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Alz50 immunoglobulin M (IgM, 1:500, courtesy of Peter Davies); chicken anti-GFP (1:1,000; Aves Labs); rabbit anti-human Aβ (1:500; IBL America); mouse anti-PHF1 IgG (1:1,000, courtesy of Peter Davies). After three washes in TBS, sections were incubated in secondary antibodies diluted in 5% NGS for 60 min at room temperature. After three washes in TBS, sections were incubated in secondary antibodies diluted in 5% NGS for 60 min at room temperature. The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse IgM, μ chain, Cy3 conjugate (1:1,000; EMD Millipore); Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-chicken (1:1,000; Invitrogen); Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit (1:500; Invitrogen); Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500; Invitrogen). After three washes in TBS, sections were mounted on microscope slides in 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories) and coverslipped. Images were recorded on a Axio Imager microscope (ZEISS) equipped with a CoolSNAP digital camera (Photometrics) and AxioVision software version 4.8. Stereological quantifications of NFTs and amyloid plaques were performed using the Computer Assisted Stereological Toolbox (Olympus). All counting was conducted blinded to genotype and treatment. Further information about the antibodies used for immunohistochemistry can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Tau protein analysis

Mouse forebrain was homogenized with a dounce homogenizer in 300 μl PBS with protease inhibitor (100:1, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and spun at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was collected for sarkosyl extraction. Protein concentration was determined with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). ELISA was performed using the Phospho(Thr231)/Total Tau Kit (MSD), following the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were run in duplicate and fitted to an eight-point standard curve to determine concentration. To isolate sarkosyl-soluble/insoluble tau, the same protein quantity of mouse brain lysate pellet was resuspended in cold TBS and centrifuged at 150,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then homogenized in 3× salt/sucrose buffer (0.8 M NaCl, 10% sucrose, 10 mN Tris base, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 150,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, adjusted to 1% sarkosyl and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Samples were then centrifuged at 150,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant and pellets were collected. Pellets were resuspended with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1% SDS and sonicated for 20 min in a Branson 2510 sonicator. Both supernatant (sarkosyl-soluble) and pellets (sarkosyl-insoluble) were then analyzed by western blot as follows: sarkosyl-soluble and insoluble fractions were mixed with 1× final lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen) and 50 mM dithiothreitol (10× Sample Reducing Agent; Invitrogen), and boiled for 5 min. Samples were loaded in 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run at 130 V for 90 min in 1× MES SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen). Proteins were then transferred to an activated polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (EMD Millipore) in 1× transfer buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 75 V for 75 min. Membranes were then blocked for 1 h using the Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) at room temperature and then incubated with a mouse anti-human Tau antibody (TAU-13, 1:2,500; BioLegend) and a chicken anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (1:5,000; EMD Millipore) in blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then washed 3 × 10 min in TBS with Tween 20, and then incubated with secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG IRDye 680RD and donkey anti-chicken IgG IRDye 800CW; both LI-COR Biosciences) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were imaged using a LI-COR Biosciences imaging station using the Odyssey software. Blots were converted to gray scale and densitometry analysis was performed in ImageJ. Further information about the antibodies used for tau protein analysis can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Statistics

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes; however, our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications (see, for example, Busche et al.17, Grienberger et al.18, Busche et al.19, and Keskin et al.20). No animals or data points were excluded from the analysis. Biochemical and histological analyses were conducted blinded to genotype and treatment, whereas in vivo microscopy and analysis were not performed blinded to the conditions of the experiments. The distributions of firing rates of neurons were analyzed using LMEMs with animal as a random factor, and fixed factors as stated in the main text. Since the distributions of firing rates were highly skewed to the right, a log transformation was used to ensure normality. This was the best Box-Cox transformation for these data. Firing rates of 0 were coded as half the lowest non-zero observed rate before the log transformation. Computations were performed using the function fitlme in the statistical toolbox of Matlab version R2017b (MathWorks). Statistical comparison between two experimental groups was assessed with a two-sided Welch’s t test; differences between multiple groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis routines and the code used in this study can be requested from the corresponding authors.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are reported in the main text and supplementary materials, stored at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A.B. Robbins, D.L. Corjuc, A.D. Roe, and E. Hudry for their excellent technical support, and all members of the Hyman laboratory for providing comments and advice throughout the project. We thank Matthias Staufenbiel for helpful discussions and experimental suggestions. We acknowledge the Genetically-Encoded Neuronal Indicator and Effector (GENIE) project and the Janelia Research Campus of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and specifically V. Jayaraman, R.A. Kerr, D.S. Kim, L.L. Looger, and K. Svoboda from the GENIE Project, Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute for making AAV.Syn.GCaMP6f publicly available. We thank Dr P Davies for kindly providing the PHF1 and Alz50 antibodies. We thank the following funding agencies for their support: M.A.B. was supported by an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (grant no. ALTF 590–2016), the Alzheimer Forschung Initiative, and the UK Dementia Research Institute. I.N. was supported by an advanced ERC grant (project RATLAND; grant no. 340063). B.T.H. received support from the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (grant no. P50AG005134), the JPB foundation, the National Institutes of Health (grant no. 1R01AG0586741), and the Tau Consortium.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0289-8.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of data availability and associated accession codes are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0289-8.

References

- 1.Hyman BT et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 8, 1–13 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H & Braak E Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82, 239–259 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR & Van Hoesen GW The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 1, 103–116 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl M et al. PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron 89, 971–982 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delacourte A et al. The biochemical pathway of neurofibrillary degeneration in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 52, 1158–1165 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L et al. Evaluation of tau imaging in staging Alzheimer disease and revealing interactions between β-amyloid and tauopathy. JAMA Neurol. 73, 1070–1077 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pontecorvo MJ et al. Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain 140, 748–763 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis J et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science 293, 1487–1491 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Götz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J & Nitsch RM Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Aβ42 fibrils. Science 293, 1491–1495 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurtado DE et al. Aβ accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am. J. Pathol 177, 1977–1988 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett RE et al. Enhanced tau aggregation in the presence of amyloid β. Am. J. Pathol 187, 1601–1612 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs HIL et al. Structural tract alterations predict downstream tau accumulation in amyloid-positive older individuals. Nat. Neurosci 21, 424–431 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quiroz YT et al. Association between amyloid and tau accumulation in young adults with autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 75, 548–556 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Z et al. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med 24, 29–38 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr JN, Greenberg D & Helmchen F Imaging input and output of neocortical networks in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14063–14068 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen TW et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499, 295–300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busche MA et al. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 321, 1686–1689 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grienberger C et al. Staged decline of neuronal function in vivo in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun 3, 774 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busche MA et al. Decreased amyloid-β and increased neuronal hyperactivity by immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s models. Nat. Neurosci 18, 1725–1727 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keskin AD et al. BACE inhibition-dependent repair of Alzheimer’s pathophysiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8631–8636 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson RJ et al. Human tau increases amyloid β plaque size but not amyloid β-mediated synapse loss in a novel mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci 44, 3056–3066 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santacruz K et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 309, 476–481 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger Z et al. Accumulation of pathological tau species and memory loss in a conditional model of tauopathy. J. Neurosci 27, 3650–3662 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Calignon A et al. Caspase activation precedes and leads to tangles. Nature 464, 1201–1204 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angulo SL et al. Tau and amyloid-related pathologies in the entorhinal cortex have divergent effects in the hippocampal circuit. Neurobiol. Dis 108, 261–276 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberson ED et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science 316, 750–754 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ittner LM et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell 142, 387–397 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeVos SL et al. Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J. Neurosci 33, 12887–12897 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zott B, Busche MA, Sperling RA & Konnerth A What happens with the circuit in Alzheimer’s disease in mice and humans? Annu. Rev. Neurosci 41, 277–297 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman DH et al. Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. JAMA 286, 2120–2127 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander GE, Chen K, Pietrini P, Rapoport SI & Reiman EM Longitudinal PET evaluation of cerebral metabolic decline in dementia: a potential outcome measure in Alzheimer’s disease treatment studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 738–745 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL & Menon V et al. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4637–4642 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley KM et al. Cerebral perfusion SPET correlated with Braak pathological stage in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 125, 1772–1781 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jelic V et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele decreases functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease as measured by EEG coherence. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 63, 59–65 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET & Hyman BT Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42, 631–639 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson PT et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 362–381 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palop JJ & Mucke L Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 17, 777–792 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickerson BC et al. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology 65, 404–411 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakker A et al. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74, 467–474 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan UA et al. Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci 17, 304–311 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoover BR et al. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron 68, 1067–1081 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Menkes-Caspi N et al. Pathological tau disrupts ongoing network activity. Neuron 85, 959–966 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatch RJ, Wei Y, Xia D & Gotz J Hyperphosphorylated tau causes reduced hippocampal CA1 excitability by relocating the axon initial segment. Acta Neuropathol. 133, 717–730 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oddo S et al. Reduction of soluble Aβ and tau, but not soluble Aβ alone, ameliorates cognitive decline in transgenic mice with plaques and tangles. J. Biol. Chem 281, 39413–39423 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sydow A et al. Tau-induced defects in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory are reversible in transgenic mice after switching off the toxic Tau mutant. J. Neurosci 31, 2511–2525 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lasagna-Reeves CA et al. Tau oligomers impair memory and induce synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type mice. Mol. Neurodegener 6, 39 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Jeugd A et al. Cognitive defects are reversible in inducible mice expressing pro-aggregant full-length human Tau. Acta Neuropathol 123, 787–805 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Castillo-Carranza DL et al. Passive immunization with Tau oligomer monoclonal antibody reverses tauopathy phenotypes without affecting hyperphosphorylated neurofibrillary tangles. J. Neurosci 34, 4260–4272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudinskiy N et al. Tau pathology does not affect experience-driven single-neuron and network-wide Arc/Arg3.1 responses. Acta Neuropathol. Commun 2, 63 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuchibhotla KV et al. Neurofibrillary tangle-bearing neurons are functionally integrated in cortical circuits in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 510–514 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jankowsky JL et al. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue β-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet 13, 159–170 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayford M et al. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science 274, 1678–1683 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Froudarakis E et al. Population code in mouse V1 facilitates readout of natural scenes through increased sparseness. Nat. Neurosci 17, 851–857 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are reported in the main text and supplementary materials, stored at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.