Abstract

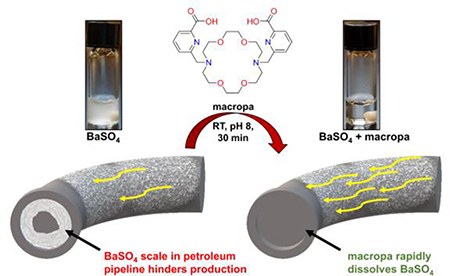

Insoluble BaSO4 scale is a costly and time-consuming problem in the petroleum industry. Clearance of BaSO4-impeded pipelines requires chelating agents that can efficiently bind Ba2+, the largest non-radioactive +2 metal ion. Due to the poor affinity of currently available chelating agents for Ba2+, however, the dissolution of BaSO4 remains inefficient, requiring very basic solutions of ligands. In this study, we investigated three diaza-18-crown-6 macrocycles bearing different pendent arms for the chelation of Ba2+ and assessed their potential for dissolving BaSO4 scale. Remarkably, the bis-picolinate ligand macropa exhibits the highest affinity reported to date for Ba2+ at pH 7.4 (log Kʹ = 10.74), forming a complex of significant kinetic stability with this large metal ion. Furthermore, the BaSO4-dissolution properties of this ligand dramatically surpass those of the state-of-the-art ligands DTPA and DOTA. Using macropa, complete dissolution of a molar equivalent of BaSO4 is reached within 30 min at RT in pH 8 buffer, conditions under which DTPA and DOTA only achieve 40% dissolution of BaSO4. When further applied for the dissolution of natural barite samples, macropa also outperforms DTPA, showing that this ligand is potentially valuable for industrial processes. Collectively, this work demonstrates that macropa is a highly effective chelator for Ba2+ that can be applied for the remediation of BaSO4 scale.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Barium, the 14th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, is the heaviest and largest non-radioactive alkaline earth (AE) metal.1,2 Administered as a suspension of BaSO4, this element has been employed for over a century as a contrast agent for X-ray imaging of the gastrointestinal tract.3 The insolubility of BaSO4 (Ksp = 1.08 × 10−10)4 is essential for its use in medicine because it prevents this toxic heavy metal from being absorbed into the body. This same physical property, however, presents a serious problem in the industrial sector. Precipitation of BaSO4 occurs frequently in oil field and gas production operations. When Ba2+-rich formation waters mix with SO42--rich seawater, an intractable scale of BaSO4 is deposited, obstructing downhole pipes and surface equipment.5 As such, BaSO4 scale is a major economic burden to the petroleum industry that slows or halts production and requires costly scale removal efforts.6,7 In addition, the scale poses a significant health hazard to petroleum workers. Naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM), particularly long-lived bone-seeking Ra2+ ions, is readily incorporated into BaSO4 and is mobilized during scale remediation, exposing humans to toxic levels of radioactivity.8,9 Hence, the efficient and safe removal of BaSO4 scale is of global significance.

The elimination of BaSO4 scale is achieved by solubilization using chelating agents.10–14 One of the most commonly used chelators is the acyclic ligand DTPA (Chart 1).12 The thermodynamic stabilities of DTPA complexes of the AEs, however, decrease with increasing ionic radius of the metal ion, rendering DTPA a low-affinity ligand for Ba2+ (log KBaL = 8.78).15 Extreme conditions of high pH (pH > 11) and heat are required to efficiently remove scale using DTPA,16–18 reflecting the fact that this ligand is not optimal for the chelation of Ba2+. The tetraaza macrocycle DOTA (Chart 1) has also been investigated for the dissolution of BaSO4.12 Despite having the highest reported thermodynamic affinity for Ba2+ in aqueous solution (log KBaL = 11.75),19–21 DOTA dissolves BaSO4 less efficiently than DTPA,22 reflecting the slow metal-binding kinetics of this macrocycle. Collectively, these limitations underscore the need to develop new ligands for Ba2+.

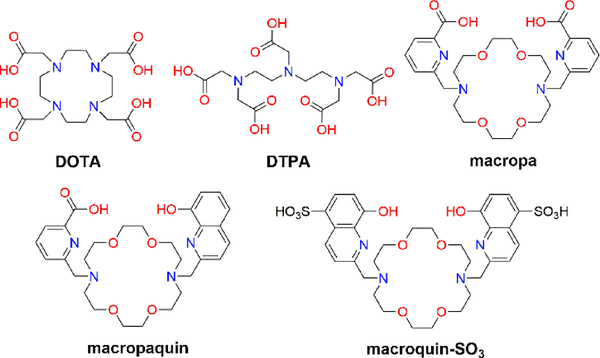

Chart 1.

Structures of the Ligands Discussed in this Work

Despite the need for new, more effective Ba2+ chelators for the removal of BaSO4 scale, few efforts to date have been directed towards this objective. The development of improved chelators for Ba2+ has further been hindered by the lack of fundamental coordination chemistry studies of this ion.23 A key challenge for the chelation of Ba2+ arises from the fact that the large AEs engage primarily in ionic, rather than covalent, binding interactions with ligands. The strength of these ionic bonds is proportional to the charge-to-size ratio of the metal center, with smaller ratios giving rise to weaker electrostatic interactions. As the largest non-radioactive +2 ion in the Periodic Table (IR = 1.35 Å, CN6),2 Ba2+ has a low charge density, resulting in coordination complexes of lower stability compared to the smaller AEs. As a result, the selective, rapid, and stable chelation of Ba2+ has remained elusive.

Based on our success in using the expanded 18-membered macrocycle macropa (Chart 1) for the chelation of the largest +3 ion, actinium (IR = 1.12 Å, CN6),24–26 we investigated the suitability of this ligand for the large Ba2+ ion. Additionally, two novel ligands, macropaquin and macroquin–SO3 (Chart 1), were evaluated to systematically probe the influence of varying the metal-binding pendent arms on Ba2+ coordination. Our studies show that macropa has the highest affinity for Ba2+ at pH 7.4 reported to date, to the best of our knowledge. This ligand also possesses excellent selectivity for large over small AEs, a feature that is not observed for conventional ligands such as DTPA and DOTA. Furthermore, macropa exhibits superior BaSO4-dissolution properties relative to DTPA and DOTA, rapidly solubilizing BaSO4 under mild conditions. These results reveal macropa to be an exceptional chelator for the large Ba2+ ion and establish proof of concept for its industrial application as a scale dissolver, demonstrating that fundamental coordination chemistry principles can be applied to satisfy unmet societal needs.

Results and Discussion

Previous studies have shown that macropa selectively binds large over small metal ions;24,27,28 notably, the affinity of macropa for Sr2+ (log KSrL = 9.57) is 4 orders of magnitude higher than for the smaller Ca2+ ion (log KCaL = 5.25).29 Based on these findings, we hypothesized that macropa may possess even higher affinity for Ba2+. Macroquin, a ligand in which the picolinate pendent arms of macropa are replaced with 8-hydroxyquinoline groups, has also been investigated.30 Ligands of this class are highly selective for Ba2+ over smaller AEs, although this selectivity has only been demonstrated in organic solvents owing to the poor aqueous solubility of these ligands.30–32 To increase aqueous solubility, we installed sulfonate groups onto the 8-hydroxyquinoline arms of the macrocycle, generating macroquin–SO3. Finally, to investigate potential metal-binding synergy between the two types of pendent arms, the mixed variant, macropaquin, was synthesized by the stepwise installation of one picolinate group and one 8-hydroxyquinoline group onto the diaza-18-crown-6 backbone. Details of the synthesis and characterization of the ligands are provided in the Supporting Information, SI (Figures S1–S4, S9–S12).

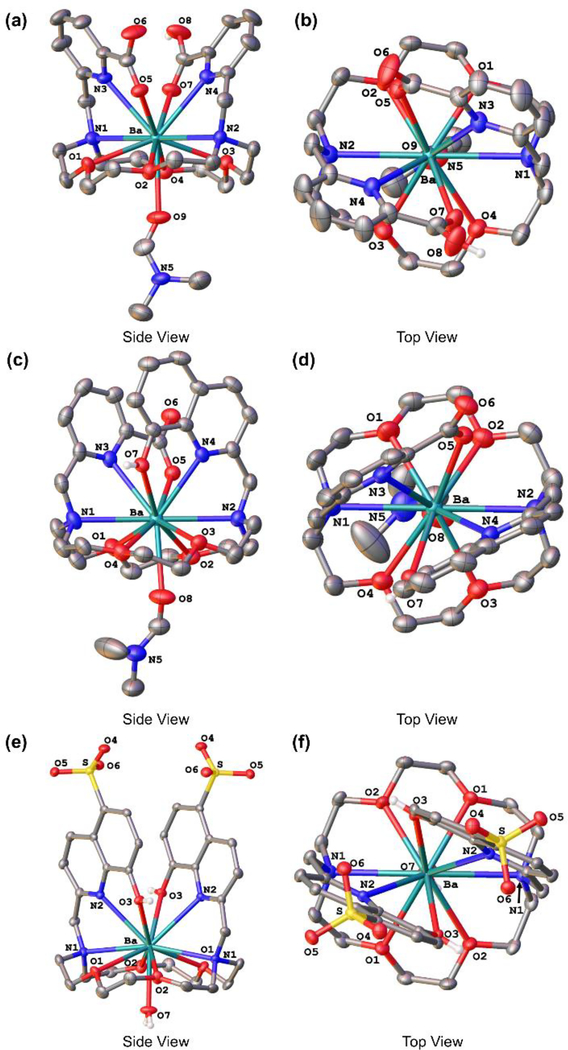

To probe the fundamental coordination chemistry of these ligands with Ba2+, their complexes with this ion were prepared (Figures S5–S8, S13, S14) and analyzed by X-ray crystallography to elucidate their solid-state structures (Figure 1, Tables S1–S4). In each complex, the Ba2+ ion is situated slightly above the diaza-18-crown-6 ring, and the two pendent arms are oriented on the same side of the macrocycle. The coordination sphere of the Ba2+ ion comprises all ten donor atoms of each ligand (N4O6), together with an oxygen atom from a coordinated solvent molecule that penetrates each macrocycle from the opposite face. Similar 11-coordinate arrangements were observed for the Ba2+ complexes of BHEE-18-aneN2O4, a diaza-18-crown-6 macrocycle bearing two pendent –CH2CH2OCH2CH2OH arms,33,34 and macroquin–Cl, in which the sulfonate groups of macroquin–SO3 are replaced by chlorine atoms.31

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structures of [Ba(Hmacropa)(DMF)]ClO4•Et2O (a,b), [Ba(Hmacropaquin)(DMF)]ClO4•DMF (c,d), and [Ba(H2macroquin–SO3)(H2O)]•4H2O (e,f). Ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Counteranions, non-acidic hydrogen atoms, and outer-sphere solvent molecules are omitted for clarity.

The ligand conformation, which can be denoted with Δ or Λ to indicate the pendent arm helical twist and δ or λ to indicate the tilt of each five-membered chelate ring,35 is identical for the three complexes. Each ligand attains the Δ(δλδ)(δλδ) conformation, present in equal amounts with its enantiomer. For complexes of macropa with other large metal ions, this conformation is also the most stable.27,29 Protonation of one picolinate arm of macropa and the 8-hydroxyquinoline arm of macropaquin gives rise to complexes of the cationic formulae [Ba(Hmacropa)(DMF)]+ and [Ba(Hmacropaquin)(DMF)]+, respectively. By contrast, macroquin–SO3 forms a neutral complex with Ba2+, [Ba(H2macroquin–SO3)(H2O)]. In this case, both phenolates are protonated to form neutral donors, but the sulfonic acid groups exist in the deprotonated anionic form. As reflected by the similar distances between Ba2+ and the two nitrogen atoms of each macrocycle, the Ba2+ ion is situated symmetrically within the macrocycle of each complex. Collectively, the structural features of these complexes suggest that macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin–SO3 can optimally accommodate the large Ba2+ ion.

To further evaluate the coordination properties of the ligands with the AEs, their protonation constants and the stability constants of their Ca2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+ complexes were measured by potentiometric titration in 0.1 M KCl (Table 1, Figures S15–S17). For comparison, corresponding values for DTPA and DOTA, the current state of the art for Ba2+ chelation, are also provided. The protonation constants of the ligands are defined in Eq. 1. The stability constants and protonation constants of the metal complexes are expressed in Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Table 1.

Protonation Constants of macropa2−, macropaquin2−, and macroquin–SO34− and Thermodynamic Stability Constants of Their Alkaline Earth Complexes Determined by pH-Potentiometry (25 °C and I = 0.1 M KCl).a

| macropa2− | macropaquin2− | macroquin–SO34− | DOTA4–b | DTPA5–c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log Ka1 | 7.41(1) (7.41)d | 10.33(4) | 9.34(4) | 11.14 | 10.34 |

| log Ka2 | 6.899(3) (6.85) | 7.15(3) | 9.43(1) | 9.69 | 8.59 |

| log Ka3 | 3.23(1) (3.32) | 6.97(2) | 6.75(4) | 4.85 | 4.25 |

| log Ka4 | 2.45(5) (2.36) | 3.24(4) | 6.62(4) | 3.95 | 2.71 |

| log Ka5 | (1.69) | 2.18 | |||

| log KCaL | 5.79(1) [5.25]e | 5.90(4) | 6.04(8) | 16.37 | 11.77 |

| log KCaHL | 8.59(2) | 8.60(4) | 3.60 | 6.10 | |

| log KSrL | 9.442(4) [9.57] | 9.19(5) | 8.62(2) | 14.38 | 9.68 |

| log KSrHL | 3.35(8) [4.16] | 8.92(2) | 8.34(4) | 4.52 | 5.4 |

| log KSrH2L | 6.920(3) | ||||

| log KBaL | 11.11(4) | 10.87(2) | 10.44(6) | 11.75 | 8.78 |

| log KBaHL | 3.76(2) | 9.76(2) | 9.24(7) | 5.34 | |

| log KBaH2L | 2.49(7) | 3.28(2) | 7.80(2) | ||

| log KʹCaf | 5.42 | 3.94 | 3.19 | 10.34 | 7.63 |

| log KʹSrf | 9.07 | 7.54 | 5.64 | 8.35 | 5.53 |

| log KʹBaf | 10.74 | 10.05 | 8.76 | 5.72 | 4.63 |

| pCag | 6.54 | 6.04 | 6.01 | 11.29 | 8.59 |

| pSrg | 10.02 | 8.50 | 6.70 | 9.30 | 6.61 |

| pBag | 11.69 | 11.01 | 9.72 | 6.76 | 6.15 |

Data reported previously for DOTA4− and DTPA5− are provided for comparison.

Ref 21, I = 0.1 M KCl.

Parenthetic values from Ref 27, I = 0.1 M KCl.

Bracketed values from Ref 29, I = 0.1 M KNO3.

Conditional stability constant at pH 7.4, 25 °C, and I = 0.1 M KCl.

Calculated from −log [M2+]free ([M2+] = 10−6 M; [L] = 10−5 M; pH 7.4; 25 °C; I = 0.1 M KCl).

A comparison of the ligand protonation constants reveals that sequential replacement of each picolinate arm of macropa by 8-hydroxyquinoline-based binding groups significantly decreases the basicity of the nitrogen atoms of the macrocyclic core to which they are attached. This trend is evidenced by the lower amine protonation constants of 7.15 (log Ka2) and 6.97 (log Ka3) for macropaquin and 6.75 (log Ka3) and 6.62 (log Ka4) for macroquin–SO3, versus 7.41 (log Ka1) and 6.899 (log Ka2) for macropa. A comparison between related ethylenediamine-derived ligands bearing either picolinate or 8-hydroxyquinoline groups also shows that the basicity of the secondary amines is lower when attached to the latter.36,37 The electron-withdrawing sulfonate groups on macroquin–SO3 give rise to more acidic phenols (log Ka1 = 9.34, log Ka2 = 9.43) compared to macropaquin (log Ka1 = 10.33). Notably, the second protonation constant of macroquin–SO3 is slightly larger than the first protonation constant. This apparent reversal in expected values may be attributed to intramolecular hydrogen bonding that slightly stabilizes the second proton; upon its removal, the hydrogen bond network is broken, and the final remaining proton becomes more acidic. This phenomenon has been previously reported for other macrocyclic ligands.38,39

Because protons compete with metal ions for binding sites on ligands, ligand basicity is an important factor that contributes to the affinity of a ligand for a metal ion at a specific pH.40,41 The overall basicity of the ligands, taken as the sum of their log Ka values, follows the order macropa (19.99) < macropaquin (27.69) < macroquin–SO3 (32.14). The speciation of the ligands reflects these overall basicity values. At pH 7.4, 43% of macropa is fully deprotonated (L2–), consistent with the low overall basicity of this ligand (Figure S18). By contrast, fully deprotonated macropaquin2– and macroquin–SO34– do not exist in solution below pH 8 (Figures S19 and S20). At pH 7.4, the monoprotonated species of macropaquin, HL–, predominates (56%), whereas macroquin–SO3 is mostly present as H2L2– (78%). On the basis of these results, macropaquin and macroquin–SO3 may chelate metal ions less effectively than macropa near neutral pH due to greater competition with protons for binding.

With the protonation constants in hand, the stability constants of these ligands with Ca2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+ were determined. Remarkably, macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin–SO3 all exhibit significant thermodynamic preferences for large over small AEs; the measured log KML values are highest for complexes of Ba2+ and lowest for complexes of Ca2+. However, the affinities of the ligands for Ba2+ and Sr2+ decrease as the picolinate arms on the macrocyclic scaffold are replaced with 8-hydroxyquinoline or 8-hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic acid arms. For example, log KBaL values of 11.11, 10.87, and 10.44 were measured for complexes of macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin–SO3, respectively, containing zero, one, and two 8-hydroxyquinoline-based pendent arms. This trend signifies that 8-hydroxyquinoline-based pendent arms may not be suitable metal-binding groups for the chelation of large metal ions such as Ba2+.

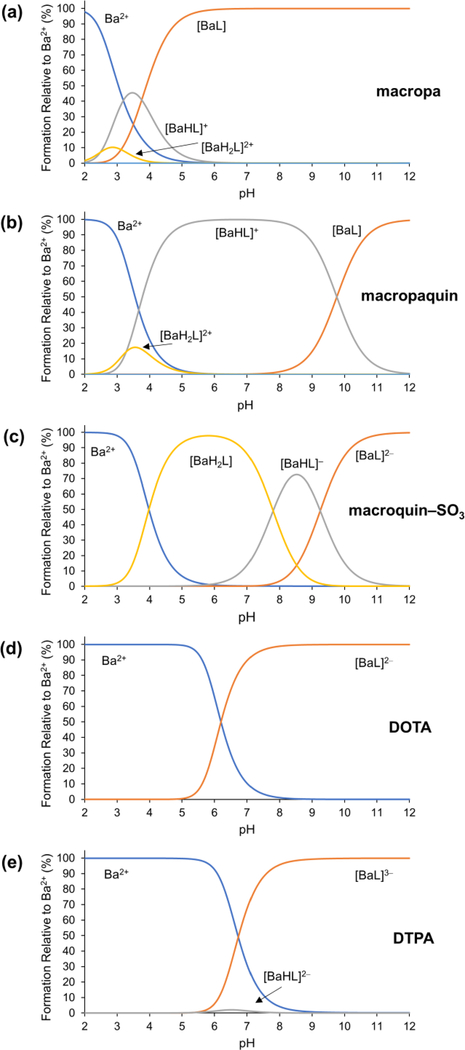

Refinement of our potentiometric titration data also revealed the presence of protonated metal complexes, or MHL and MH2L species, for all three ligands bound to Ca2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+ (Figures 2 and S21–26). The inclusion of these species within our solution phase model is consistent with the results from X-ray crystallography, which also identified these species in the solid state (Figure 1). The speciation diagrams for solutions of Ba2+ and the three ligands, based on the thermodynamic constants in Table 1, are shown in Figure 2. The major species present at pH 7.4 is the ML species for macropa, the MHL species for macropaquin, and the MH2L species for macroquin–SO3. These data indicate that the 8-hydroxyquinoline donors retain their basicity when bound to the Ba2+ ion. The presence of two such donors in macroquin–SO3 gives rise to the large prevalence of the protonated complex MH2L near neutral pH.

Figure 2.

Species distribution diagrams of (a) macropa, (b) macropaquin, (c) macroquin–SO3, (d) DOTA, and (e) DTPA in the presence of Ba2+ at [Ba2+]tot = [L]tot = 1.0 mM, I = 0.1 M KCl, and 25 °C.

In comparing the thermodynamic properties of these ligands to the commonly employed ligands DOTA and DTPA, it is noteworthy that the log KBaL value of 11.11 for macropa is substantially larger than that for DTPA (8.78) and only 0.64 log units lower than that for DOTA, indicating that macropa is a high-affinity ligand for Ba2+. A more accurate reflection of thermodynamic affinity in aqueous solution, however, can be expressed using conditional stability constants, which account for the effect of protonation equilibria of the ligands on complex stability.43,44 The conditional stability constants (log Kʹ) of the AE complexes at pH 7.4 are given in Table 1. The log KʹBa value of 10.74 for macropa is 5–6 orders of magnitude greater than those for DOTA (5.72) and DTPA (4.63). Macropa also exhibits higher affinity for Ba2+ at pH 7.4 than macropaquin (log Kʹ = 10.05) and macroquin–SO3 (log Kʹ = 8.76). From these values, macropa emerges as remarkably superior to all other ligands for the chelation of Ba2+ at near-neutral pH.

Another measure of conditional thermodynamic affinity of a ligand for a metal ion is provided by pM values (Table 1), which are defined as the negative log of the free metal concentration in a pH 7.4 solution containing 10–6 M metal ion and 10–5 M ligand.45 Larger pM values correspond to higher affinity chelators because they indicate that there is a smaller concentration of free metal ions under these conditions at equilibrium. The pBa values of DOTA and DTPA are only 6.76 and 6.15, respectively, reflecting the presence of a significant amount of free Ba2+ at pH 7.4 (Figure 2). By contrast, 90% of Ba2+ is already bound by macropa at pH 4.0 and 99% is complexed at pH 5.1, consistent with the high pBa value of 11.69 for this ligand. Furthermore, macropa is 1.17-fold and 1.79-fold more selective for Ba2+ over Sr2+ and Ca2+, respectively, as determined by the ratio of the corresponding pM values. By contrast, these selectivity values are <1 for DOTA and DTPA, emphasizing their poor affinities for the large Ba2+ ion at pH 7.4.

Having demonstrated that macropa chelates Ba2+ with high thermodynamic stability and selectivity, the kinetic inertness of this complex was examined in comparison to that of macropaquin and macroquin–SO3. We first challenged the Ba–L complexes with 1000 equiv of La3+, a metal that forms a complex of high thermodynamic stability with macropa (log KLaL = 14.99).27 The substitution of Ba2+ with La3+ was monitored at RT and pH 7.3 by UV-vis spectrophotometry (Figures S27–S29). Ba–macropa and Ba–macropaquin exhibited moderate stability, giving rise to similar half-lives of 5.45 ± 0.20 min and 6.07 ± 0.13 min, respectively. By contrast, Ba–macroquin–SO3 underwent transmetalation with La3+ much more rapidly (t½ = 0.65 ± 0.05 min), indicating that macroquin-SO3 cannot adequately retain Ba2+ under these conditions.

Because Ba2+ possesses bone-seeking properties, the stability of the Ba2+ complexes in the presence of hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH), HAP), the predominant mineral that comprises bone, was also evaluated.46,47 HAP was suspended in solutions containing the complexes formed in situ (1.1 equiv L, 1.0 equiv Ba2+) in pH 7.6 buffer, and the amount of Ba2+ remaining in the liquid phase, reflecting intact Ba–L complex, was determined by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (GFAAS) (Figure S30). Whereas free Ba2+ is adsorbed by HAP in less than 10 min, Ba–macropa and Ba–macropaquin respectively retained 82% and 68% of this ion after 20 h. Ba–macroquin–SO3 displayed the least stability in the presence of HAP, with only 17% of the complex remaining intact after 20 h. Taken together, the results of these challenges demonstrate that Ba–macropa and Ba–macropaquin are considerably more stable than Ba-macroquin–SO3 under extreme conditions of large excesses of competing metal ions. This feature may be important for Ba2+ chelation in industrial applications, such as scale dissolution, because numerous other metal ions are present during these processes. The inferior kinetic stability of Ba–macroquin–SO3 relative to the other two complexes correlates with the lower thermodynamic affinity of this ligand for Ba2+ and is most likely a consequence of the fact that the diprotonated Ba2+ complex of macroquin-SO3, MH2L, is the major species at pH 7.4 (Figure 2). This complex is expected to be substantially more labile than the ML species due to decreased electrostatic interactions between the ion and ligand.

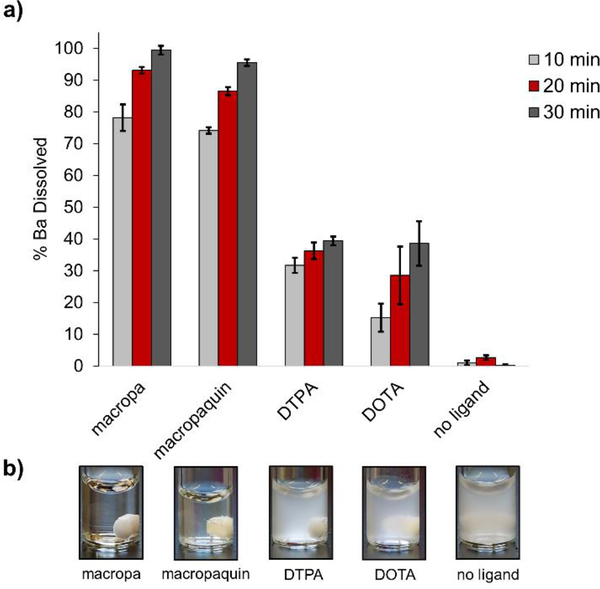

The encouraging results of the thermodynamic and kinetic stability studies prompted us to evaluate the feasibility of employing macropa and macropaquin as BaSO4 scale dissolvers. First, a suspension of BaSO4 in pH 8 NaHCO3 was formed by combining Ba(NO3)2 (4.53 mM) with excess Na2SO4 (13.48 mM), simulating the mixing of incompatible waters that produces BaSO4 scale in petroleum operations. The resulting BaSO4 suspension was treated with ligand (5 mM), and the amount of dissolved Ba2+ was measured by GFAAS (Figure 3). Macropa rapidly solubilized 78% of BaSO4 in just 10 min and afforded complete dissolution after 30 min. Likewise, macropaquin dissolved 95% of BaSO4 in 30 min. By contrast, the conventional ligands DOTA and DTPA dissolved only 40% of BaSO4 within this same time, underscoring the inferior solubilizing properties of these ligands at pH 8.

Figure 3.

Dissolution of BaSO4 by macropa, macropaquin, DTPA, and DOTA. (a) Dissolution at RT and pH 8 was initiated by the addition of chelator (5 mM) to a suspension of BaSO4 (4.53 mM Ba(NO3)2 and 13.48 mM Na2SO4). Barium content in solution was measured by GFAAS after 10, 20, and 30 min. (b) Samples from dissolution experiments after 30 min.

The dissolution of BaSO4 by macropa, DTPA, and DOTA was further evaluated in pH 11 NaCO3 buffer (Figure S31) to match the caustic conditions that are applied in the industrial setting. Impressively, macropa solubilized >95% of the BaSO4 in just 5 min. DTPA also dissolved nearly all the BaSO4 in this same time. The improved dissolution ability of DTPA at pH 11 versus pH 8 reflects the greater proportion of the fully deprotonated ligand (DTPA5–) present at pH 11, which favors Ba–DTPA complex formation. These results are consistent with the fact that the petroleum industry only uses this ligand under conditions of high pH.16–18 The similar rates at which macropa and DTPA solubilize BaSO4 at pH 11 suggest that macropa possesses remarkably fast Ba2+-binding kinetics. The macrocycle DOTA, by contrast, was unable to completely dissolve all the BaSO4. After 30 min, only 75% dissolution was reached, signifying that the kinetics of metal incorporation for DOTA remain slow even at high pH.

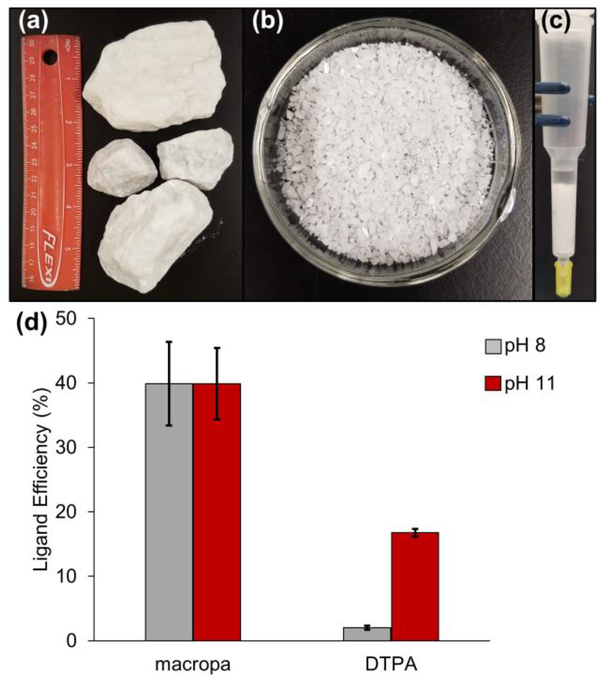

We next investigated the ligand-promoted dissolution of crude barite ore, which is composed predominately of BaSO4, as a model for the solid deposits of natural scale that plague the petroleum industry. Barite rocks (Figure 4a) obtained from Excalibar Minerals (Katy, TX) were milled and sieved to isolate particles between 0.5 and 2 mm (Figure 4b). To simulate production tubing clogged with BaSO4 scale, polypropylene columns were filled with barite (3 g), to which solutions of macropa or DTPA at pH 8 or 11 were added (Figure 4c). The concentration of each ligand solution was approximately 48 mM, consistent with the dilute compositions of scale dissolvers used industrially.11,13,16,18,48 After a soak time of 1 h, the ligand solution was eluted from the column, and the concentration of dissolved barium was measured by GFAAS and converted to ligand efficiency (Eq. 4).

| (4) |

Figure 4.

Barite dissolution efficiency of macropa and DTPA. (a) Large rocks of crude barite ore were crushed with a hammer. (b) The barite was sieved to isolate particles between 0.5 and 2 mm. (c) To simulate petroleum pipes clogged with BaSO4 scale, columns were filled with barite (3 g), and then solutions of macropa or DTPA (~48 mM) at pH 8 and pH 11 were added. (d) After a soak period of 1 h, ligand efficiency, or the percent of ligand saturated with Ba2+, was determined by measuring the concentration of barium in the eluate by GFAAS.

In Eq. 4, Baexp is the concentration of barium measured in the eluate, and Bamax is the maximum concentration of barium that can be chelated by each ligand, calculated from the concentration of each ligand applied to the column and assuming a 1:1 M:L binding model. As shown in Figure 4d, the ligand efficiency of macropa at pH 8 is 40%, indicating that nearly half of the ligand solution was saturated with Ba2+ following exposure to barite for 1 h. DTPA, by contrast, was practically incapable of dissolving barite at this pH, giving rise to a ligand efficiency of only 2%. Macropa remained equally as effective at pH 11, again displaying a ligand efficiency of 40%. By contrast, even at pH 11, the dissolution efficiency of DTPA was only 17%, less than half that observed for macropa. Collectively, these results indicate that macropa maximally dissolves barite at or below pH 8, underscoring its superior affinity for Ba2+ near neutral pH.

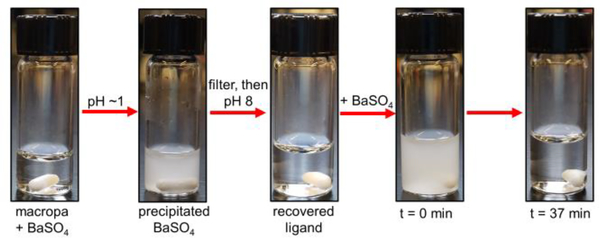

Lastly, the capacity for recovery and reuse of macropa post-BaSO4 dissolution was assessed qualitatively (Figure 5). A sample of macropa-dissolved BaSO4 (9.66 mM macropa, 8.74 mM Ba(NO3)2, 26.04 mM Na2SO4) was acidified to pH 1 with concentrated HCl to protonate the ligand, inducing Ba2+ decomplexation and precipitation as BaSO4. The macropa solution was isolated by filtration, basified to pH 8 with 2 M NaOH, and combined with another portion of BaSO4. Within 40 min, no visible precipitate remained in the vial, signaling that the recycled macropa dissolved all the BaSO4. Subsequently, the ligand was recovered and reused for BaSO4 dissolution four more times with a negligible loss in efficacy or speed of dissolution (Figure S33). These results demonstrate the facile and economic reuse of macropa, an attractive feature that will facilitate its implementation in industry.49

Figure 5.

Ligand recovery and reuse. A solution of macropa-dissolved BaSO4 was acidified to release the Ba2+ from the ligand as BaSO4. After filtration of the precipitated BaSO4 and basification of the solution, the recovered ligand was successfully reused for another cycle of BaSO4 dissolution.

Conclusion

In summary, three ligands based on the expanded diaza-18-crown-6 macrocycle were evaluated for their abilities to chelate the large Ba2+ ion. Macropa exhibits unprecedented affinity for Ba2+ at pH 7.4, possessing a log Kʹ value of 10.74. The Ba2+ complexes of both macropa and macropaquin display substantial kinetic stability when challenged with La3+ or HAP, whereas macroquin–SO3 rapidly releases Ba2+ under these conditions. Additionally, macropa and macropaquin can efficiently dissolve BaSO4 under RT and near-neutral pH conditions. This feature was further reflected in dissolution studies involving authentic barite ore samples, which showed macropa to be superior to the state-of-the-art chelator DTPA. The promising Ba2+-chelation properties of this ligand will render it useful for the dissolution of BaSO4 scale deposits, fulfilling an important unmet need in the petroleum industry.

More broadly, these results reveal key features that are required for stable coordination of the heavy AE ions. Namely, the observation that picolinate donors provide superior coordination properties for Ba2+ in contrast to 8-hydroxyquinoline donors will guide future ligand design efforts for this underexplored metal ion. These results have further implications in the realm of radiochemistry, where these chelators may be applied for the chelation of Ra2+. Due to both concerns about radiological contamination of 226Ra in NORM and the great therapeutic potential of 223Ra for the treatment of cancer, a better understanding of AE chemistry will advance efforts to chelate Ra2+ for these important applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Vojtěch Kubíček (Charles University, Prague, The Czech Republic) for his valuable guidance with potentiometry and Excalibar Minerals (Katy, TX) for providing us with a sample of barite ore.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by Cornell University and by a Pilot Award from the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical and Translational Science Center, funded by NIH/NCATS UL1TR00457. This research made use of the NMR Facility at Cornell University, which is supported in part by the NSF under award number CHE-1531632.

Footnotes

N.A.T. and J.J.W. have filed a provisional patent on the application of this class of ligands for BaSO4 scale dissolution.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Experimental details, compound characterization, and supporting figures and tables (PDF)

Crystallographic information files (PDF)

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Beryllium, Magnesium, Calcium, Strontium, Barium and Radium In Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd Ed.; Greenwood N, Earnshaw A, Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 1997; pp 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Shannon RD Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schott GD Med. Hist 1974, 18, 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).CRC Handbook of Chemstry and Physics, 87th ed.; Lide DR, Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Li J; Tang M; Ye Z; Chen L; Zhou YJ Dispersion Sci. Technol 2017, 38, 661–670. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Clemmit AF; Ballance DC; Hunton AG The dissolution of scales in oilfield systems. SPE14010/1, presented at SPE, Aberdeen, U.K. September 10–13, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Crabtree M; Eslinger D; Fletcher P; Miller M; Johnson A; King G Oilfield Rev. 1999, 11, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zielinski RA; Otton JK Naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM) in produced water and oil-field equipment—An issue for the energy industry. U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet FS–142–99, September, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ghose S; Heaton B In The Natural Radiation Environment VII: VIIth Int. Symp. On the NRE; Radioactivity in the Environment; Elsevier, 2005; Vol. 7, pp 1081–1089. [Google Scholar]

- (10).de Jong F; Reinhoudt DN; Torny-Schutte GJ; van Zon A Novel macrocyclic polyethers and the use of salts thereof for dissolving barium sulfate scale. Brit. UK Pat. Appl GB2024822A, January 16, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lakatos I; Lakatos-Szabó J; Kosztin B Comparative study of different barite dissolvers: Technical and economic aspects. SPE 73719, presented at SPE, Lafayette, LA, U.S.A., February 20–21, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Almubarak T; Ng JH; Nasr-El-Din H Oilfield scale removal by chelating agents: An aminopolycarboxylic acids review. SPE-185636-MS, presented at SPE, Bakersfield, CA, April 23, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mason DJ Formulations and methods for mineral scale removal. U.S. Patent Appl US20170369764A1, December 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mason DJ Composition for removing naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM) scale. U.S. Patent Appl US20170313927A1, November 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Martell AE; Smith RM Critical Stability Constants: Vol. 1; Plenum Press: New York; London, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Putnis A; Putnis CV; Paul JM. The efficiency of a DTPA-based solvent in the dissolution of barium sulfate scale deposits. SPE 29094, presented at SPE, San Antonio, TX, U.S.A. February 14–17, 1995, 773–785. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dunn K; Yen TF Environ. Sci. Technol 1999, 33, 2821–2824. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Putnis CV; Kowacz M; Putnis A Appl. Geochem 2008, 23, 2778–2788. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Stetter H; Frank W; Mertens R Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 767–772. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Delgado R; Fraûsto Da Silva JJR Talanta 1982, 29, 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Clarke ET; Martell AE Inorg. Chim. Acta 1991, 190, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang K-S; Tang Y; Shuler PJ; Dunn KJ; Koel BE; Yen TF Effect of scale dissolvers on barium sulfate deposits: A macroscopic and microscopic study. Paper 02309, presented at NACE, January 1, 2002.

- (23).Poonia NS; Bajaj AV Chem. Rev 1979, 79, 389–445. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Thiele NA; Brown V; Kelly JM; Amor-Coarasa A; Jermilova U; MacMillan SN; Nikolopoulou A; Ponnala S; Ramogida CF; Robertson AKH; Rodríguez-Rodríguez C; Schaffer P; Williams C Jr.; Babich JW; Wilson JJ Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 14712–14717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Thiele NA; Wilson JJ Cancer Biother. Radiopharm 2018, doi: 10.1089/cbr.2018.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kelly JM; Amor-Coarasa A; Ponnala S; Nikolopoulou A; Williams C Jr.; Thiele NA; Schlyer D; Wilson JJ; DiMagno SG; Babich JW J. Nucl. Med 2018, Accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Roca-Sabio A; Mato-Iglesias M; Esteban-Gómez D; Tóth É; de Blas A; Platas-Iglesias C; Rodríguez-Blas T J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3331–3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jensen MP; Chiarizia R; Shkrob IA; Ulicki JS; Spindler BD; Murphy DJ; Hossain M; Roca-Sabio A; Platas-Iglesias C; de Blas A; Rodríguez-Blas T Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 6003–6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ferreirós-Martínez R; Esteban-Gómez D; Tóth É; de Blas A; Platas-Iglesias C; Rodríguez-Blas T Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 3772–3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Su N; Bradshaw JS; Zhang XX; Song H; Savage PB; Xue G; Krakowiak KE; Izatt RM J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 8855–8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhang XX; Bordunov AV; Bradshaw JS; Dalley NK; Kou X; Izatt RM J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 11507–11511. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bordunov AV; Bradshaw JS; Zhang XX; Dalley NK; Kou X; Izatt RM Inorg. Chem 1996, 35, 7229–7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bhavan R; Hancock RD; Wade PW; Boeyens JCA; Dobson SM Inorg. Chim. Acta 1990, 171, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hancock RD; Siddons CJ; Oscarson KA; Reibenspies JM Inorg. Chim. Acta 2004, 357, 723–727. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Jensen KA Inorg. Chem 1970, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Boros E; Ferreira CL; Cawthray JF; Price EW; Patrick BO; Wester DW; Adam MJ; Orvig C J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 15726–15733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang X; De Guadalupe Jaraquemada-Pelaéz M; Cao Y; Pan J; Lin K-S; Patrick BO; Orvig C Inorg. Chem 2018, doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hancock RD; Motekaitis RJ; Mashishi J; Cukrowski I; Reibenspies JH; Martell AE J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2 1996, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Rohovec J; Kyvala M; Vojtisek P; Hermann P; Lukes I Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2000, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Martell AE; Hancock RD; Motekaitis RJ Coord. Chem. Rev 1994, 133, 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Doble DMJ; Melchior M; O’Sullivan B; Siering C; Xu J; Pierre VC; Raymond KN Inorg Chem 2003, 42, 4930–4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Schmitt-Willich H; Brehm M; Ewers CL; Michl G; Müller-Fahrnow A; Petrov O; Platzek J; Radüchel B; Sülzle D Inorg. Chem 1999, 38, 1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Alberty RA Eur. J. Biochem 1996, 240, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Burgot JL Conditional Stability Constants In Ionic Equilibria in Analytical Chemistry. Springer, New York, 2012; pp 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Harris WR; Carrano CJ; Raymond KN J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 2722–2727. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Li WP; Ma DS; Higginbotham C; Hoffman T; Cutler CS; Jurisson SS Nucl. Med. Biol 2001, 28, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Cawthray JF; Creagh AL; Haynes CA; Orvig C Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 1440–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Jordan MM; Williams H; Linares-Samaniego S; Frigo DM New insights on the impact of high temperature conditions (176°C) on carbonate and sulphate scale dissolver performance. SPE-169785, presented at SPE, Aberdeen, U.K., May 14–15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Morris RL; Paul JM Method for regenerating a solvent for scale removal from aqueous systems. PCT Int. Appl WO9206044A1, April 16, 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.