Abstract

A statewide decennial survey was sent to practicing dentists holding sedation or general anesthesia permits to identify office sedation/general anesthesia trends and practices over the last 10 years. This survey constitutes the third such survey, spanning a total of 20 years. Of the 234 respondents in the 2016 survey, 34% held an Illinois moderate sedation permit and 64% held a general anesthesia permit. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons represented the majority of respondents (143/234; 61%). The remainder of responses were from general dentists (39; 17%) pediatric dentists (32; 14%), periodontists (16; 7%), dentist anesthesiologists (3; 1.3%) and 1 periodontist/dentist anesthesiologist. Surveys over the 20 years revealed the following significant trends: an increase in practitioners current in advanced cardiac life support certification, an increase in the number of non-oral maxillofacial surgeons with a sedation permit, an increase in providers of moderate sedation, and an increase in offices equipped with end-tidal CO2 and electrocardiogram monitoring. However, a number of providers were identified as not compliant with certain state mandates. For example, many respondents failed to meet minimum office team staffing requirements during sedation, hold semiannual office emergency drills, and establish written emergency management protocols.

Key Words: Dental sedation, Dental anesthesia, Morbidity and mortality, Practice parameters

In 1996 and 2006, all Illinois dental sedation and general anesthesia (GA) permit holders were surveyed, with results published in Anesthesia Progress. Information was acquired to show some of the aspects of outpatient dental sedation practices.1,2 In 2016, a statewide decennial survey was again conducted to investigate the office sedation/anesthesia practices among Illinois dental sedation permit holders and to identify the trends within the 20-year study. As Illinois is a central state with a diverse population, including both large urban and rural populations, the survey identifies populations common throughout the United States. Surveys of this type are useful to the dental anesthesia profession, public health policy advocates, and regulatory agencies.

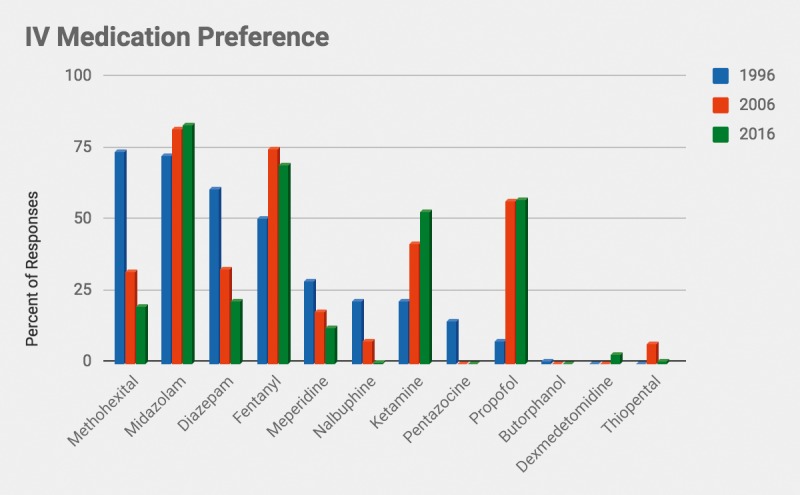

Over the 20 years which have passed since the initial survey was conducted, many changes have occurred in the field of dental anesthesia in Illinois. The state of Illinois has required advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training for Permit A (moderate sedation); it was previously required only for Permit B (deep sedation/GA) holders. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) has mandated the use of end-tidal CO2 monitoring during moderate sedation as well as during deep sedation and GA for its members.3 The availability of agents such as midazolam and propofol in generic forms and the availability of sevoflurane have also changed clinical practice over the 20 years, with a decline in the use of methohexital, diazepam, morphine, and meperidine.

Over this same time period, the safe use of sedation and GA in dental practices has come under considerable nationwide public scrutiny because of widely published anesthesia-related deaths. This survey was designed to analyze the practices of clinicians and provide information to assist clinicians in evaluating their own practices. Additionally, this survey provides regulatory and professional associations needed information when revising clinical care standards.

Dental office sedation and GA are provided on a continuum from moderate sedation to GA, commonly with the same drugs being used but in different amounts, techniques, or combinations, making strict comparisons difficult. Furthermore, sedation and GA are regulated by 50 different states and administered by dentists with varying levels of training. For this reason, the American Dental Association has assumed a leadership role by publishing its Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists. The latest revised version4 was issued in October 2016. These guidelines set practice parameters that can be followed by all practitioners. However, they do not supersede individual state requirements. The latest version states that the dentist must “comply with their state laws, rules, and/or regulations.” Other professional bodies, including the AAOMS and the American Society of Anesthesiologists, have published additional guidelines to help promote safe ambulatory anesthesia provided to the public. The Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation (IDFPR) issues dental sedation and GA permits and enforces the rules and regulations affecting dentistry.5 Illinois does not issue licenses limited to oral (PO) sedation only but rather to the level of sedation rendered. Sedation in Illinois has 3 categories: minimal sedation (no permit required), moderate (conscious) sedation (Permit A), and deep sedation/GA (Permit B). Minimal sedation is characterized as the use of PO anxiolytics or nitrous oxide, individually or in combination, with minimal depression of the level of consciousness. Monitoring by clinical observation is sufficient. The use of moderate (conscious) sedation in Illinois requires Permit A licensing with the following requisites: (a) certification of completed sedation training program of at least 75 hours of didactic and clinical study with an additional minimum of 20 case experiences; (b) an anesthesia team consisting of a dentist with Permit A, a hygienist or assistant with sedation assistant training, and an additional assistant; and (c) all team members must have current basic life support certification and the sedating dentist must have current ACLS or pediatric advanced life support (PALS) certification. The training for the hygienist or dental assistant (DA) must consist of a course resulting in certification after a combined 12 hours of didactic and clinical study provided by AAOMS or a similar organization approved by the IDFPR. The use of deep sedation/GA requires Permit B with the following requisites: (a) certification of completion of an advanced training program in anesthesiology of at least 24 months or current eligibility to obtain diplomate status from the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (ABOMS) or have a state specialty license in OMFS and (b) all team members must have current basic life support certification and an anesthetizing dentist with either current ACLS or PALS certification.

The IDFPR also mandates that offices performing moderate (conscious) sedation must be equipped with a sphygmomanometer, stethoscope, oxygen delivery system with full face mask to provide positive pressure, emergency drugs, pulse oximeter, laryngoscope, advanced airway devices (endotracheal tubes or laryngeal mask airway), and automated external defibrillator or manual defibrillator. However, neither electrocardiography nor CO2 monitoring is required. In addition to the Permit A office equipment requirements noted above, Permit B offices performing deep sedation/GA must have temperature monitoring and continuous electrocardiogram monitoring. As mentioned, the AAOMS 2012 Parameters of Care mandated those providing moderate or deep sedation and GA to have continuous capnography monitoring. Although continuous capnography monitoring is also required for those providing moderate anesthesia, deep anesthesia, and GA in the current American Dental Association Guidelines for Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists4 for adults, because these guidelines were approved in 2016, the use of capnography is likely not reflected in this survey, nor have the Illinois rules and regulations reflected this change.

Other studies have surveyed dentists performing sedation/GA to characterize techniques and demographics as well. Boynes et al6 surveyed dentists throughout the nation and found a wide variation of sedation/GA care in background training, auxiliary staff, and methods of sedation. However, details regarding the anesthetic agents used were lacking and focused on PO premedication.

Unlike other surveys that have been done of this type, this study looked at the demographics of providers, compliance with state regulations, readiness for emergency events, and use of specific intravenous (IV) and PO agents. This study also analyzed various aspects of outpatient dental sedation and GA in Illinois in 2016 and how current practices compare to practices over the 20 years since the primary investigator conducted similar surveys in 2006 and 1996.

METHODS

The 2016 survey study was reviewed and classified as exempt from the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (2016-0886). A survey was mailed to all dentists in Illinois registered through the IDFPR with either Permit A or Permit B (n = 605). The survey consisted of 29 questions on 2 pages. The method of mailing and recording the surveys was performed in a similar manner to the 2006 method. Envelopes contained a cover letter, the survey, and a return envelope with the return address and a postage stamp. The surveys had numerical codes to match the responder to a responder key. A noninvestigator was designated as the key manager to record those who responded. The identities of the respondents remained anonymous to the investigator. The key manager would open the returned envelopes, note which surveys had been returned, and forward the completed surveys to the investigators. Three months after the first mailing, a second mailing to nonresponders was conducted to increase the response rate. The survey mailing took place from September 2016 through January 2017.

The data were recorded in Microsoft Excel and Statistical Analysis Systems for descriptive and multivariate analysis. At no time was there any inquiry of or recording of personal identification information of the respondents or of the patients treated. Data published in the 2006 and 1996 studies were used to evaluate trends found in this 2016 study.

RESULTS

Thirty mailed surveys were returned as undeliverable and excluded from the study. The adjusted total surveys mailed to registered sedation permit holders was 575. Two hundred thirty-four (n = 234) surveys were returned, for a response rate of 41%. This response rate was significantly lower than the response rates from the 2006 and 1996 studies, which were 69% (n = 244) and 71% (n = 305), respectively. Some of the returned surveys were not fully completed or were answered by retired practitioners. All questions answered were included in the data. However, some questions had a total response number less than 234.

General demographics of the respondents were collected. Most of the respondents represented an older age group, with 31% over 60 years of age, 30% in their 50s, 23% in their 40s, and 15% in their 30s. The average current length in practice was 22.2 years. This was an increase from 2006 and 1996 (20.7 years and 16.3 years, respectively). The average age of the respondents in 2006 was 49.8 (median of 51.0). Given the 2006 and 1996 respondents' lower numbers of years in practice, an overall greater response from older age groups was noted in 2016. That the survey was distributed by mail may have contributed to the lower response rate from younger providers, as they may be more responsive to participation in an electronic survey.

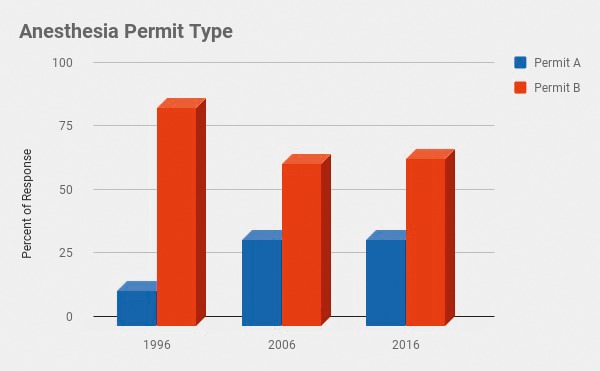

The IDFPR sedation registry of 605 permits had 49% Permit A and 51% Permit B holders. The respondents to the survey indicated a greater proportion of Permit B providers compared to Permit A providers. Of those who responded to the 2016 survey, 34% were Permit A holders and 66% were Permit B holders. In comparison, for 2006 responses, 34% were Permit A and 64% were Permit B holders; the 1996 responses had 14% Permit A and 86% Permit B holders (see Figure 1). The proportion of Permit B holders initially decreased from 1996 to 2006, then stabilized from 2006 to 2016.

Figure 1.

Anesthesia permit type.

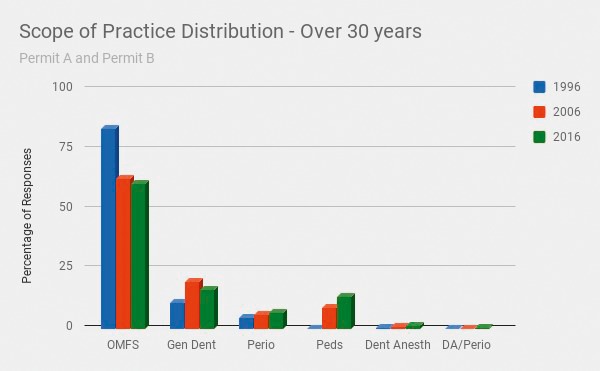

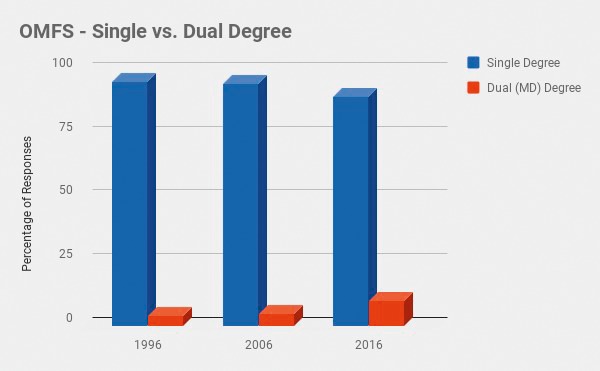

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons (OMFSs) represented the greatest proportion (61%) of those who responded, which is similar to the 2006 results (63%). The second most represented group was general dentists (16.7%), followed by pediatric dentists (13.7%). Figure 2 compares the proportion by specialty of those who responded and compares these to the 2006 and 1996 results. Ten percent of OMFSs had medical degrees, whereas in 2006 and 1996, 5% and 4% of OMFS responders were medically trained (see Figure 3). OMFSs with board certification increased from 68% in 1996 to 79% in 2016.

Figure 2.

Scope of practice distribution over 20 years.

Figure 3.

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons—single versus dual degree.

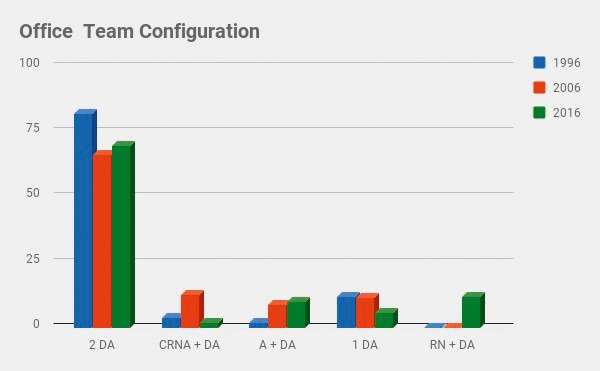

The IDFPR requires holders of both Permit A and Permit B to have a team consisting of 3 members that will remain in the room during the sedation procedure on the patient. The office sedation team configuration varied significantly over the 20 years of collected data. In 2016, 70% of sedation permit holders had 2 DAs, 12% had a nurse and a DA, 10% used dentist anesthesiologists and a DA, and 2% used a nurse anesthetist and a DA. Six percent were noncompliant with Illinois rules by having only 1 DA present (70% were Permit A holders). Compared to 2006, 67% of practitioners had 2 DAs, 13% had a nurse anesthetist and a DA, 9% used a dentist anesthesiologist and a DA, and 12% did not comply by having only 1 DA present. Figure 4 illustrates the various office team configurations along with results from 2006 and 1996.

Figure 4.

Office team configuration. DA indicates dental assistant; CRNA, certified registered nurse anesthetist; A, dentist anesthesiologist; and RN, registered nurse.

The 5 most commonly used IV medications in 2016 were midazolam (84%), fentanyl (70%), propofol (58%), ketamine (53%), and diazepam (22%). Figure 5 shows the various IV medications used and compares them to the results from the 2006 and 1996 surveys. Methohexital showed a steady decrease from being most common in 1996 (74%) to declining in 2006 (32%) and again in 2016 (20%). Further analysis of the 2016 respondents' use of methohexital indicate its use to be associated with years in practice. Seven percent of those who had practiced less than 10 years used methohexital, compared to 7% of those in practice 10–20 years, 20% in practice 20–30 years, and 35% of those who had practiced over 30 years.

Figure 5.

Intravenous medication preference.

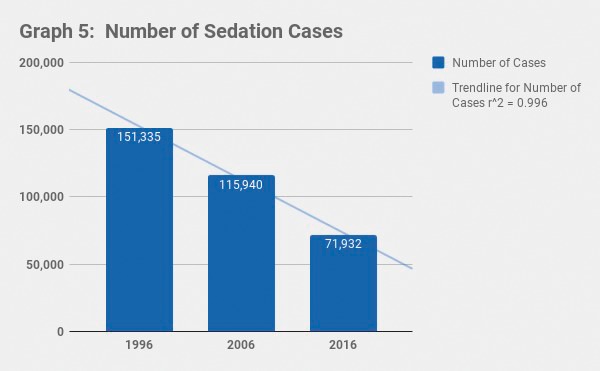

The responses for number of sedation cases performed in 2016 appeared skewed because of strong outliers. Using the geometric mean, the estimated total number of sedations performed in the state of Illinois during the 2016 calendar year was 71,932 (95% CI, 57,964–89,232), which is significantly lower than the 2006 report of 115,940 cases. However, the number of cases in 2006 decreased from 151,335 in 1996 (see Figure 6). There is an apparent steady decrease in the number of sedation cases performed over 20 years. The average number of sedation/GA cases performed by practitioner per year was 336. The total number of sedation/GA cases per year represents about 0.6% of the Illinois population; this proportion of the overall Illinois population was down from 0.9% in 2006.

Figure 6.

Number of sedation cases.

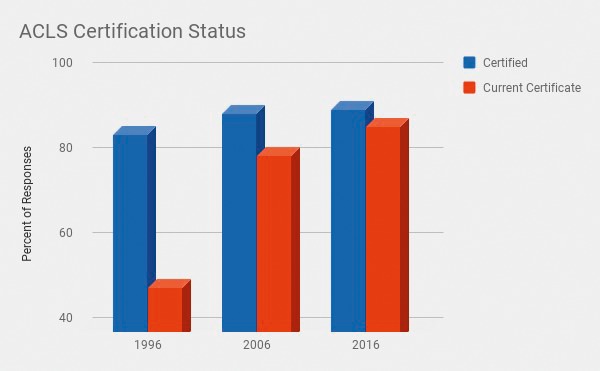

Survey questions were asked regarding the practitioner's background training and certifications. Eighty-two percent of respondents received their sedation or GA training from postgraduate or general practice residencies, compared to 13% from continuing moderate sedation education courses and 5% from a dental anesthesiology residency. Fifty-eight percent of practitioners had membership in the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology. ACLS and PALS certification requires renewal every 2 years. When practitioners were asked regarding the status of their ACLS/PALS certifications, 91% had previously completed certification for ACLS (90% in 2006 and 85% in 1996; see Figure 7) whereas only 87% had their certification current. Forty-six percent of respondents had once completed PALS certification and 39% had a current PALS certification. Of those who held Permit A, 62% had current ACLS certification. Of Permit A holders, 3.7% had neither ACLS or PALS certifications current, whereas 99% of Permit B holders had current certification. Forty-eight percent of Permit A holders and 33% of Permit B holders had current PALS certification. Current certification in ACLS or PALS is required for both Permit A and Permit B holders.

Figure 7.

Advanced cardiac life support certification status.

Multiple survey questions were asked to obtain information on office practices and equipment. Eighty percent of practitioners used electrocardiographic monitoring routinely. Ninety-nine percent utilized continuous pulse oximetry monitoring routinely. Continuous end-tidal CO2 monitoring was used by 72% of the practitioners. Automated electronic defibrillators were present in 96% of the offices, compared to 63% in 2006. For IV cases, IV fluids were always used during sedation/GA procedures by 87% of practitioners and only sometimes used by 8% of practitioners, presumably reflecting PO sedation cases. Emergency drills were performed in 80% of offices, and an emergency action plan was present in 96% of offices. An emergency action plan, semiannual emergency drills, and presence of an automated external defibrillator or manual defibrillator are all requirements of Illinois rules and regulations. Ten percent of offices were accredited by an organization such as the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care or the Joint Commission.

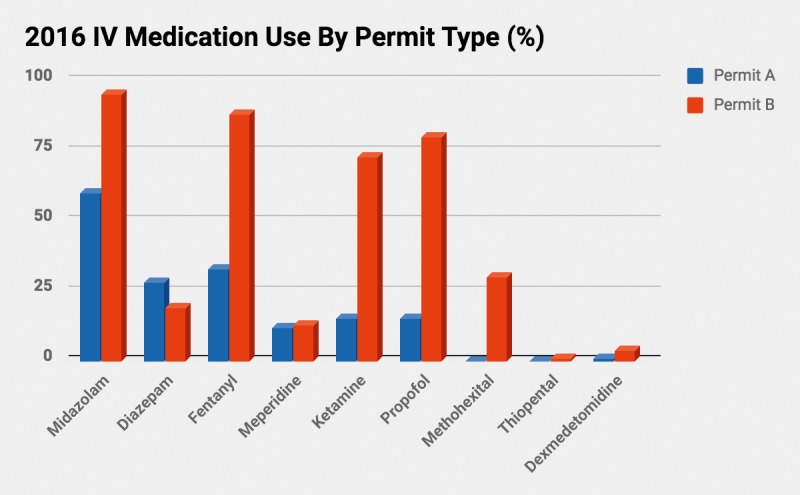

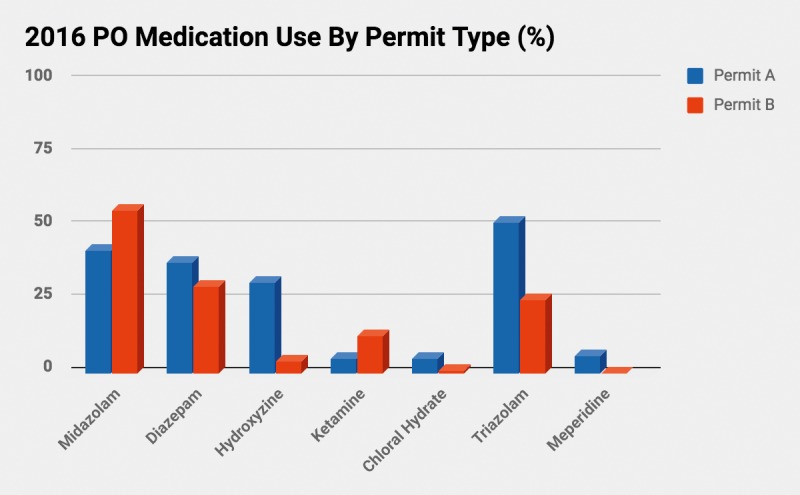

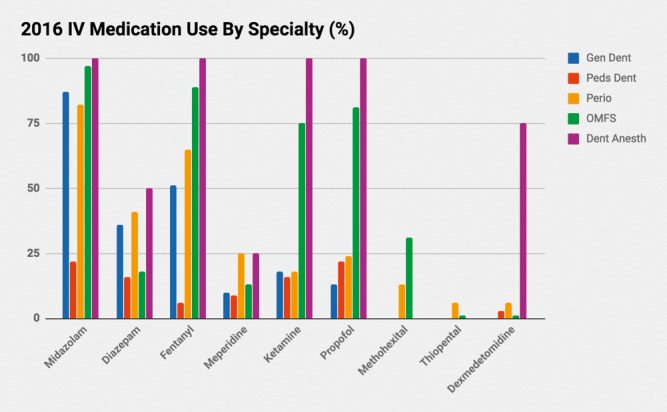

Covariates were analyzed for descriptive statistics of the IV and PO medications used by either Permit A or Permit B holders and also by dental specialty. The top 3 IV medications used by Permit A holders were midazolam (60%), fentanyl (33%), and diazepam (28%). The top 3 IV medications used by Permit B holders were midazolam (95%), fentanyl (88%), and propofol (80%). Ketamine was used by 78% of Permit B holders. Fifteen percent of Permit A holders used propofol. Or these, 67% (10% of Permit A holders) used propofol for over 75% of their sedations. See Figure 8 for complete illustration of the proportions of Permit A and Permit B holders' use of IV medications during 2016. The use of PO medications among Permit A and Permit B holders is compared in Figure 9. Permit A holders most commonly used PO triazolam (52%), compared to 56% of Permit B holders who commonly used PO midazolam. Figure 10 illustrates the proportion of dental specialists' use of IV medication during 2016. The dentist anesthesiologists' use of IV medication type closely followed OMFS preferences. Most common IV medications used by OMFSs included midazolam (97%), fentanyl (89%), propofol (81%), and ketamine (75%). When looking at the use of propofol by specialists, the data showed 24% of periodontists, 22% of pediatric dentists, and 13% of general dentists use this medication during their sedations. Ketamine was used during sedations by 18% of periodontists and general dentists and 16% of pediatric dentists.

Figure 8.

Intravenous medication use in 2016 by permit type (%).

Figure 9.

Oral medication use in 2016 by permit type (%).

Figure 10.

Intravenous medication use in 2016 by specialty (%).

Survey questions were asked to assess the prescribing of PO opioids after oral surgery procedures. Seventy-three percent of respondents prescribed an opioid after surgery. Of those who prescribed opioids, 50% prescribed for 4–7 days, 37% for 3 days, 12% for 1–2 days, and almost 2% for over 7 days.

Lastly, questions regarding adverse outcomes were asked. One Permit B holder reported a patient who experienced a hemorrhagic stroke, with that patient recovering without any lasting disability.

DISCUSSION

Dental office sedation/GA practices tend to be a common point of interest to those in the profession as well as the public. The media has recently alerted the public by drawing attention to sedation/GA safety in dental offices. One particular case in California made national headlines when a 6-year-old boy named Caleb Sears died after deep sedation/GA in an oral and maxillofacial surgery office. Caleb's Law was passed to develop stricter laws and rules for dentists providing deep sedation/GA to children under 7 years of age. Dentists have the moral and professional responsibility to adhere to state laws and regulations as well as the guidelines and standards established by professional organizations (eg, American Dental Association, AAOMS) to provide safe and effective sedation/GA. This privilege to provide office-based sedation/GA has allowed the profession to flourish and provides a unique experience and service to its patients.

One area of concern is the use of propofol and ketamine by moderate (conscious) sedation providers. Although specific drugs are not listed as prohibited in the rules and regulations, the following requirement for moderate (conscious) sedation is included in the Illinois Rules and Regulations:5 “drugs and/or techniques used must carry a margin of safety wide enough to render unintended loss of consciousness unlikely.” Although this is obvious to the experienced practitioner who provides deep sedation routinely, neither propofol nor ketamine meets this requirement. Yet the survey findings indicate that among the moderate sedation permit holders, 15% used propofol, and 67% of these used propofol in 75% of their cases. A similar number of Permit A holders also report using ketamine as well. Ketamine produces a state of dissociative anesthesia where patients are unresponsive. Propofol, especially when combined with other sedatives and/or opioids, has a high likelihood of rendering the patient unconscious. These medications are generally reserved for those with advanced formal training in deep sedation and GA because of their narrow therapeutic margin such that an unintended deep level of sedation is easily achieved.7–9

The most significant and concerning finding in the 2016 survey indicated that dentists in the State of Illinois were not 100% compliant with established state rules and regulations. These include:

Pulse oximetry monitoring not used by 1% (possibly error).

Sedation/GA team consisting of at least 3 persons (ie, dentist and 2 assistants or operating dentist, separate anesthesia provider and 1 assistant). Six percent admitted to having only 1 assistant.

Lack of emergency preparedness plan. Only 96% compliance was reported.

Only 80% reported having semiannual emergency drills and exercises.

Lack of current ACLS (or PALS) certification by Permit A and Permit B holders—this should be 100% compliant.

The 2016 survey final question asked providers if there were any deaths, disabilities, or injuries during or after treatment under sedation or GA over the last 10 years. It was interesting to find that only 1 respondent, a Permit B holder, reported a patient suffering from hemorrhagic stroke, who fortunately recovered without any lasting disability. There were, however, 8 respondents who did not answer either yes or no. According to an official of the IDFPR, there had been 10 deaths related to dental sedation/GA procedures over the last 10 years. The fact that no mortalities were reported from this 2016 survey brings several points to question. First, did this survey adequately reflect the population of practitioners with adverse outcomes? If not, the revealed noncompliance rates are likely underestimates. Do practitioners with poor outcomes avoid participating in surveys of this type? Do practitioners with significant adverse outcomes simply relocate out of state? Of those who responded to this survey, none reported adverse events requiring emergent intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or contacting of emergency medical services for transfer to a hospital. The lack of respondents disclosing morbidity and mortality in an anonymous survey prevents linking clinical techniques and practices to adverse outcomes.

As it is doubtful that practitioners would intentionally disregard state laws, it appears that some practitioners are not aware of the state requirements and are therefore not compliant with them. In Illinois, there is no state requirement for regular office/practitioner sedation/GA evaluations or inspections. The AAOMS does require its members to participate in an office evaluation program every 3 years. A program such as this might help keep practitioners up to date in current practices but applies only to oral surgeons. Illinois does require its sedation permit holders to complete 9 hours of continuing education per renewal cycle. However, this may not update them on current laws and rules. Because nearly half of sedation permits are issued to non-AAOMS members, that means half of the practitioners do not have input on a regular basis from an outside source about current requirements and trends. The Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care and the Joint Commission are also organizations that provide regular accreditation services to dental offices so that standards can be updated. In this 2016 study, only 10% of the Illinois respondents representing this profession had their offices accredited.

The pertinent and critical results from this survey were presented to the State of Illinois. In February of 2018, the Illinois Division of Professional Regulation issued a letter to all registered permit holders to improve adherence to the regulatory statutes, which was a reflection of the findings from this study. The profession has so far managed to maintain relative autonomy in the provision of sedation/GA. However, lack of compliance and negligence on the part of practitioners may jeopardize this treasured professional autonomy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This survey was affiliated with the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Dentistry. The survey was endorsed and sponsored by the Illinois Dental Society of Anesthesiology and the Illinois Society of Oral Maxillofacial Surgeons. Thanks to Howard Alstrom, DDS, past president of the Illinois Dental Society of Anesthesiology and current private practice general dentist, who assisted with editing. Special thanks to Eric Lloyd, MS, for providing the statistical analysis, and to Nicholas Mechas, DMD, for assisting with the survey distributions and data recording. IRB: 2016-0886.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flick WG, Green J, Perkins D. Illinois dental anesthesia and sedation survey for 1996. Anesth Prog. 1998;45:51–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flick WG, Katsnelson A, Alstrom H. Illinois dental anesthesia and sedation survey for 2006. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:52–58. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[52:IDAASS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Parameters of care: Clinical practice guidelines for oral and maxillofacial surgery (AAOMS ParCare 2012) J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:ANE-1–ANE-22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Dental Association. Guidelines for the use of sedation and general anesthesia by dentists. Adopted by the ADA House of Delegates; October: 2016. Available at: http://www.ada.org/%7E/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/anesthesia_use_guidelines.pdf?la=en Accessed February 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illinois Dental Practice Act. Ill Admin Code Database. (2014);68(7b):1220.500–1220.530. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boynes SG, Moore PA, Tan PM, Jr, Zovko J. Practice characteristics among dental anesthesia providers in the United States. Anesth Prog. 2010;57:52–58. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-57.2.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker DE. Pharmacodynamic considerations for moderate and deep sedation. Anesth Prog. 2012;59:28–42. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-59.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southerland J, Brown L. Conscious intravenous sedation in dentistry: a review of current therapy. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60:309–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon J-Y, Kim E-J. Current trends in intravenous sedative drugs for dental procedures. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016;16:89–94. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2016.16.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]