Abstract

Physician burnout is a national crisis with medicine among occupations with higher suicide risk, at 1.8 times the national average. Few pathology departments address this issue, and even fewer residency programs offer formal resiliency training. We implemented a high-stress environment resiliency strategy and an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-compliant curriculum to our residency program. Its purpose was to apply initiatives employed in the finance industry, then to measure their effectiveness. Utilizing methods from financial companies such as Goldman Sachs, we adopted the following initiatives in our residency program: (1) approach burnout as a dilemma requiring a tridimensional strategy: providing wellness training for the individual, programmatic group strategies, and an institutional wellness plan; (2) formalize a wellness curriculum, implementing wellness talks focused on stress prevention, management, and treatment; (3) offer free sessions with resilience coaches, psychological help, Employee Assistance Program, and chaplain services; (4) modify our mentorship program, pairing first-year residents with senior residents; (5) implement mindfulness practices; (6) provide easy access to volunteer opportunities and networking; (7) offer fitness center discounts. Effectiveness was measured through 2 surveys of 13 residents representing day 0 (before wellness initiatives were implemented) and at 1 year. Results indicate a significant improvement in utilization of wellness tools. This study demonstrates that wellness and resilience can be taught. Our ultimate goals are to increase wellness among pathology residents, to prepare them for a high-stress environment before entering the workforce, and to prepare them to incorporate the tools they have learned into their new workplaces.

Keywords: burnout, wellness, pathology residency, wellness curriculum, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, stress prevention, residency program, resilience

Introduction

Burnout in the workforce is characterized by exhaustion (physical, mental, and/or emotional), cynicism, and lack of personal accomplishment.1,2 The end-stage consequence of burnout is disengagement. Engagement, at the opposite extreme, is characterized by high energy, dedication, and finding a sense of purpose at work. Studies nationwide suggest that more than 50% of US physicians experience symptoms of burnout.3-5 Patient satisfaction is constructed on a foundation of healthcare provider wellness and satisfaction. When providers are engaged and happy, the result is a more efficient and safe encounter with patients. Burnout increases the rate of medical errors, malpractice risk, employee turnover, and affects the quality of life of the provider. This makes physicians more prone to substance abuse, broken relationships, and suicide. Consequently, quality of care, patient safety, and patient satisfaction suffer. The burnout dilemma has a multidimensional structure, involving the individual, the group, and the system.6 Healthcare organizations have a vested interest in nurturing provider engagement and satisfaction.

Interventions to prevent burnout should be a shared responsibility of individual healthcare providers and the organizations for which they work. In the United States of America in the 1990s, healthcare organizations developed the Triple Aim of healthcare, which considered patient satisfaction, quality of care, and cost reductions.7 It was not until the 2000s when some organizations incorporated the Quadruple Aim of healthcare. The Quadruple Aim still considers and puts patient quality care and satisfaction at the center stage, with aligned cost stewardship, but it also includes the satisfaction of the staff and healthcare providers.8 At Loyola Medicine, we are fortunate to work for an organization that not only has a mission statement which addresses the care of the staff (Quadruple Aim of Healthcare) but also recognizes and wants to take steps to prevent burnout and increase resilience.

Our system includes a 547-licensed bed, quaternary care academic institution, a community hospital with 254 beds, and a recently incorporated community hospital with 374 beds. Our institution recognized the predicament of physician burnout affecting healthcare facilities across the country. In November 2016, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and Areas of Work Life Balance Survey were administered to the faculty. Shortly after, in December 2016, a group of volunteers were trained to acquire information, education, and resources to recognize and address symptoms of burnout. This group became known as the Resiliency Team. The team is composed of 23 to 25 physicians from multiple specialties, coaches, psychologists, and social workers who work together to create strategies for wellness across the institution. This group affords coaching services specific to burnout issues, connections to psychological help, volunteer opportunities, physical health offerings, peer support, and other strategies to promote wellness and prevent burnout. In March 2017, the Physician Resiliency website was created. This website listed wellness resources for physicians including information on wellness and burnout and resources such as the National Suicide Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255), local Employee Assistance Program (EAP) contact numbers, Second Victim Phenomenon resources, volunteer opportunities, physical fitness information, Resiliency Coaches list with e-mails and phone numbers, pastoral care information, psychological assistance, and other assistance for common life issues through a web-based library of resources provided by Loyola’s HR Department.

Pathology is historically not considered as a high-risk burnout specialty.2,9 However, at our institution, the 2016 MBI results put our department at a similar rate of burnout as that of our clinical colleagues. In June 2017, the results of the survey were disseminated to the faculty. Since then, the Resilience Team meets quarterly addressing issues related to wellness of the medical staff and trainees and continues training for resilience coaches. Institutionally, and aligning with our Quadruple Aim Mission and Vision, the team works together with hospital leaders and administrators to provide an improved work environment. Examples of successes of this collaboration include changes in compensation plan, adding an extra holiday, and the opening of a new doctors’ lounge. Additionally, multiple grand rounds and informational conferences on wellness and resilience were held.

A residency program director’s survey conducted in 2014 indicated that 92% of program directors estimated that more than 50% of residents show signs of burnout.10 In a recent study, nearly half of residents across all specialties, and 62% of residents in some specialties, reported symptoms of burnout.11 In February of 2018, the first ever Wellness Week for Residents was organized by a group of multidisciplinary residents, program directors, and resiliency coaches. Offerings such as wellness/mindfulness talks and group painting sessions resulted in increased bonding across specialties, creating a sense of community for our trainees. In the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, in July 2017, spot survey of pathology residents indicated an overall need and interest in wellness/resiliency training.

The subsequent section describes the efforts and initiatives developed during fiscal year 2017-2018. A description of each strategy, changes implemented in the development of a new wellness curriculum, and the data collected evaluating these measures are described. Preparing residents to become resilient and aware of the ill effects of burnout is paramount to ensure long-lasting career satisfaction. Our methods and experience can be modeled by other residency programs to promote wellness among trainees and faculty.

Methods and Participants

At a residents’ meeting in July 2017, an unannounced spot survey was administered to the residents and fellows present at this particular meeting. The survey consisted of soliciting opinions about 3 positive aspects of the residency program or the department, 3 frustrations, and 3 events or perceived problems they would like to change. The opinions were handwritten in an anonymous fashion. Papers were collected at the end of the meeting. This spot survey was completed by trainees prior to any plans for educational intervention, and it was the catalyst for creating a Pathology Residency Wellness program. Based on this spot survey highlighting the need for wellness education, a Wellness Curriculum following our Department of Pathology standard format for rotations was created (Table 1). This curriculum encompasses the 6 core competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) criteria. Other strategies employed were modeled after wellness initiatives utilized by companies such as Goldman Sachs. These include access to coaches, fitness center discounts, and mindfulness techniques.

Table 1.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Compliant Pathology Residency Wellness Curriculum With Program Objectives and Core Competencies.

| Program description | The overall purpose of the Wellness Talks with the Department of Pathology trainees is to improve resilience, provide tools and resources to combat burnout and navigate stress, educate trainees on a variety of well-being topics, and increase the joy, humanity, and wellness of trainees and providers. Under the guidance of a trained resilience coach and faculty member, and through a series of monthly meetings, all trainees will have the opportunity to learn and put in practice strategies to aim for a more fulfilling and joyful career. |

| Duration | The wellness talks are provided once a month to all trainees with faculty advisor:

|

| Program goals | The goals of this training are to incorporate the knowledge, practice, and experience that a resident should have to be effective in managing life at work and outside of work, keeping purpose in their medical career, and increasing overall joy of practicing medicine. |

| Program Objectives and Core Competencies | |

| Patient and self-care | Residents must be able to provide care that is compassionate, appropriate, and effective, specifically:

|

| Medical knowledge | Residents must demonstrate knowledge about established and evolving data and information on healthcare wellness, and the application of this knowledge in their life, specific topics of discussion include:

|

| Practice-based learning and improvement | Residents must be able to investigate and evaluate their own care practices, appraise, and assimilate scientific evidence, and improve their practice of self-care, group care, and patient care, specific examples include:

|

| Interpersonal and communication skills | Residents must demonstrate interpersonal and communicational skills that result in effective information exchange and teaming with professional associates, patients and patients’ families, specific examples of desired activities include:

|

| Professionalism | Residents must demonstrate a commitment to excellence, professional service, adherence to ethical principles, and sensitivity to diverse patient populations, specifically:

|

| System-based practice |

|

Subsequently, residents participated in 2 new surveys to gauge the effectiveness of the Wellness Program. Both data surveys were voluntary and dependent on resident participation. These 2 surveys were conducted representing level of wellness education at day 0 (before the wellness curriculum was developed) and at 1 year after wellness education commenced. These surveys anonymously asked 17 trainees to answer a series of questions scoring them on a scale from 1 to 10. Questions 1 to 5 were answered on a scale of how much residents agreed with the statement, with 1 being strongly disagree to 10 being strongly agree. Questions 6 to 12 were answered on a scale of how many times the activity was performed over the 12-month period before and the 12-month period after the Wellness Program began. While some components of statistical survey validation were utilized, such as the establishment of face validity and the clean collection of data, the surveys are intended to be a pilot for future data gathering and statistical analysis of the effectiveness of wellness education. Ongoing survey processes will include principal components analysis and measurement of scale reliability.

Residents and fellows were exposed to monthly wellness talks where they were introduced to information and strategies to build resilience. Attendance was voluntary. All residents, except for those off campus, attended each meeting. The curriculum was administered during noon meetings with lunch being provided. Different wellness topics were discussed by a single faculty member who was also the Associate Residency Program Director and an Associate Certified Life, Career, and Executive Coach. Confidentiality agreements were critical. The faculty member present at the meetings was not to discuss any conversation topics or issues unless agreed on by the group. A typical monthly 1-hour session was designed to include wellness education in addition to practical individual and program-driven measures. These measures include debriefings of stressful situations or encounters with patients and or faculty members, mindfulness practices, and development of team building activities at the department level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Design of Typical 1-Hour Wellness Talk Session.

| Time for celebration or gratitude reflection | 10 minutes |

| Wellness topic for discussion presented by the faculty following the curriculum schedule | 25 minutes |

| Action steps based on prioritization of desired improvements list | 15 minutes |

| Mindfulness practice | 10 minutes |

The Wellness Education Curriculum, which was implemented into the monthly wellness talks, integrated components of wellness and information about resources available in our institution. The curriculum encourages residents to be present at meetings, participate in discussions, and complete assigned and/or suggested strategies. Residents are expected to assume a portion of informal discussion during meetings and commit to at least one wellness initiative. When feasible, residents participate in activities, volunteer opportunities, and/or projects concerning wellness with other departments.

In addition, our already functioning departmental faculty mentorship program was emphasized. The mentorship program consisted of pairing first year residents with a faculty member the residents selected, to guide them and counsel them in their career and human aspects of our specialty and profession. Residents and mentors met in pairs at a minimum of twice during the academic year. The mentorship program was assessed annually at our residency program evaluation meeting.

Results

Information collected from 15 pathology residents (4 PGY1, 4 PGY2, 3 PGY3, and 4 PGY4, and a total of 6 females and 9 males) on the unannounced spot survey in July 2017 was reviewed prior to the development of the Wellness Education Curriculum. This curriculum was created with several topics for discussion, following our departmental guidelines, and in compliance with the ACGME core competencies.12 Between 15 and 17 residents and fellows participated in the monthly wellness talks. The only topics brought up outside the meeting to the Department of Pathology Chair or Department Administrator were those that included action steps to improve our department.

As a group, we developed our own mission and vision statements (Table 3). After a review of various literatures on burnout, attendance at several burnout and resilience conferences, and formalized coaching certification training, the faculty in charge of wellness talks developed topics for discussion. These topics included general aspects of burnout (Table 4).

Table 3.

Wellness Mission and Vision Statements.

| Wellness Program mission statement | To creatively work on improving the health, joy, humanity, and satisfaction of our Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine trainees. |

| Wellness Program vision statement | Our group provides initiatives, tools, and action steps to continuously improve our workplace environment resulting in enhanced provider and patient satisfaction. |

Table 4.

Topics for Discussion.

|

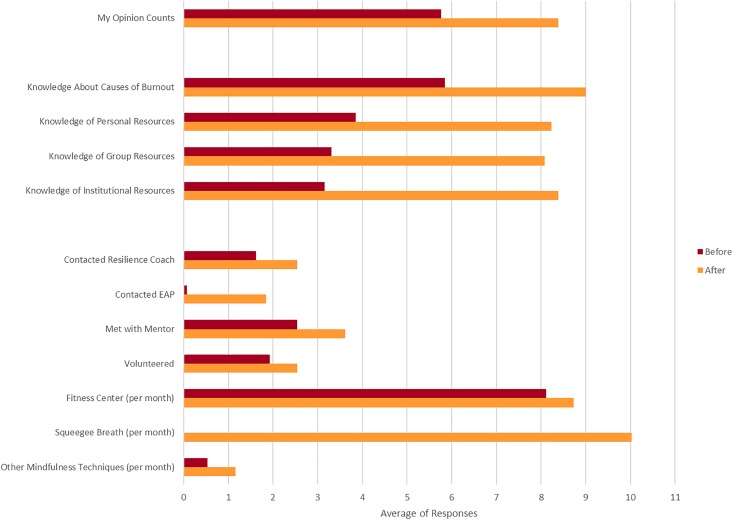

Thirteen of the 17 “day 0 and 1-year” surveys are represented in the data, as 4 surveys were missing data or did not adhere to survey instructions (Tables 5 and 6). Results were averaged across all 13 participants for both surveys. The surveyed averages of the responses for both the before and after surveys are indicated in Figure 1. On average, residents indicated that the belief that their opinions were considered when decisions are made improved by 45%, while their knowledge about causes of burnout improved by 54%. The surveyed average gauge of knowledge of personal, group, and institutional resources shows improvement of 114%, 144%, and 166%. Additionally, every individual survey showed improvement in each of these areas. Paired t tests resulted in a 2-tailed P value of .00001 on all 5 questions which assessed level of agreement on statements of personal wellness knowledge, indicating an extremely high level of statistical significance on the increased agreement with each of these statements. While many of the activities from questions 6 to 12 are not being utilized by all of the residents, all activities did show an average increase in utilization when comparing the 12 months prior to the Wellness Program beginning to the 12 months after it began. While the averages of improvements are modest on several of the activities, the results of Wellness Education are evident as the number of responses in the “0” category in questions 6 to 12 has decreased across the board (Table 6). More residents are beginning to utilize the activities discussed in Wellness Education. These survey data results showed interval changes with general trends supporting a more positive environment and individual control of stress compared to baseline data.

Table 5.

Statements of Personal Wellness Knowledge Before the Wellness Program Began and at 1 Year After the Program Began (on a Scale of 1-10, where 1 is Strongly Disagree and 10 is Strongly Agree.

| Before/After | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | Average | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| I feel my opinions and suggestions are considered when decisions are made | |||||||||||

| Before | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5.8 |

| After | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 8.4 |

| I have knowledge about causes of burnout | |||||||||||

| Before | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5.8 |

| After | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9.0 |

| I have knowledge about personal resources I can use to improve my wellness | |||||||||||

| Before | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 |

| After | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 8.2 |

| I have knowledge about group resources I can use to improve my wellness | |||||||||||

| Before | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 |

| After | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 8.1 |

| I have knowledge about institutional resources I can use to improve my wellness | |||||||||||

| Before | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 |

| After | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 8.4 |

Table 6.

Utilization Frequency of Wellness Techniques in the 12 Months Before and the 12 Months After the Wellness Program Began.*

| Before/After | Number of Occurrences per Time Period | Average | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 + | ||

| Contacted a resilience coach (12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| After | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Contacted the EAP (12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| After | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Met with my mentor (12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| After | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.6 |

| Utilized volunteerism (12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.9 |

| After | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Utilized the fitness center or exercised (per week over 12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 6 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 |

| After | 6 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 |

| Utilized the 30-second squeegee breath (per month over 12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| After | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Utilized other wellness techniques (per month over 12-month period) | ||||||||||||

| Before | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| After | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 |

Abbreviation: EAP, Employee Assistance Program.

*Total over each 12-month period, times per week over each 12-month period, or times per month over each 12-month period, as labeled.

Figure 1.

Average of wellness survey responses (for the periods 12 months before and after the Wellness Program began).

Discussion

Data about physician burnout in the United States overwhelmingly point to a national crisis that puts being a physician among the occupations with higher suicide risk, previously reported as 1.8 times the national average.13,14 Pathology is not an exception and mirrors other medical specialties listed for burnout risk at about 42%.15 At the recent annual meeting of the Association of Pathology Chairs and Program Directors (APC/PRODS, July 2018), an informal poll revealed that not every department of pathology and laboratory medicine addresses this issue for the faculty or offers formal resilience training for the residents and fellows. Burnout signs and symptoms extend to all colleagues in the laboratory and the healthcare arena. Statistics of the epidemiology of burnout may differ for nurses, technologists, laboratory scientists, and physicians in other specialties. However, such a systemic matter requires more than one solution to confront it.

Our ultimate goals are to increase wellness among pathology residents to prepare them for a high-stress environment before entering the workforce and to increase their ability to incorporate the learned tools and initiatives into their new workplace. We based our educational intervention on the concept of both training on burnout prevention development of strategies at the departmental/institutional levels to support wellness, such as the addition of a floating holiday, the allocation of space for a new doctors’ lounge, and continued discussion regarding reduction of administrative burden. Our results demonstrate that we were not only able to formalize and provide training and opportunities to enhance the wellness of our pathology residents and fellows but also provide a forum for trainees to decompress and fight burnout symptoms as a group. The increased overall wellness and interest demonstrated by residents in our department has had a profound effect on the understanding the department has regarding the prevention of burnout.

We anticipate our experience and success at Loyola University Medical Center in developing fundamental initiatives toward wellness and the well-being of our trainees can serve as an opportunity for other departments of pathology and laboratory medicine in implementing wellness programs. In this way, we hope to create a culture of open communication, knowledge, and access to resources to maintain and improve the well-being of providers in the workplace. The Wellness Curriculum could be easily adapted by residency programs in pathology or other specialties, as it is fully compliant with the ACGME core competencies.

The monitoring of our evolving program continues. Ongoing yearly surveys to assess resident experiences and involvements in resilience training are expected to target new opportunities for improvement as our established departmental and institutional initiatives progress. In fact, a system-wide residents’ wellness week was already successfully celebrated in February 2018, and February 2019, with participation across all specialties, and primarily developed by and for residents.

Our study did not have a control group of nonparticipants, and therefore, comparative studies could not be performed. In addition, the surveys the residents were subjected to were not validated surveys, but were rather administered to answer internal questions regarding the newly created Wellness Curriculum. Even though this curriculum could be adapted to other specialties, our group of trainees is fairly small and other departments or specialties may encounter difficulty in applying the strategies we used.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the pathology trainees for participating in the surveys and the program. The authors would also like to acknowledge Loyola Medicine as an institution for providing resources to minimize stress and combat burnout for all physicians, including the creation of a resilience team.

Authors’ Note: The abstract of this work was presented as a poster at the 2018 APC PRODS Annual Meeting in San Diego, CA, July 15-19, 2018; see https://doi.org/10.1177/2374289518788096.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Titus K. Frontline dispatches from the burnout battle. CAP Today. June 2018 https://www.captodayonline.com/frontline-dispatches-burnout-battle/. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 3. Shanafelt TE, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parks T. Report reveals severity of burnout by specialty. AMA News. January 31, 2017. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/report-reveals-severity-burnout-specialty. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 5. Wilson W, Raj JP, Narayan G, Ghiya M, Murty S, Joseph B. Quantifying burnout among emergency medicine professionals. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2017;10:199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drummond D. Stop Physician Burnout: What to do When Working Harder Isn’t Working. Collinsville, Mississippi: Heritage Press Publications, LLC; 2014:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27:759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hernandez JS, Wu RI. Burnout in pathology: suggestions for individual and systemwide solutions. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2018;7:166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89:443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S. Milestones Guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2016. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Resources. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 13. Andrew LB, Brenner BE. Physician suicide. Medscape. August 1, 2018. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/806779-overview. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 14. Kishore S, Dandurand DE, Mathew A, Rothenberger D. Breaking the culture of silence on physician suicide. NAM Perspectives. 2016. https://nam.edu/breaking-the-culture-of-silence-on-physician-suicide/. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 15. Luedke K. James Hernandez, MD, weighs in on physician and pathologist burnout. Medpage Today. June 29, 2018. https://www.medpagetoday.com/mayo/article/500829. Accessed April 24, 2019.