Abstract

Compared to women, men are less likely to seek help for mental health difficulties. Despite considerable interest, a paucity in evidence-based solutions remains to solve this problem.

The current review sought to synthesize the specific techniques within male-specific interventions that may contribute to an improvement in psychological help-seeking (attitudes, intentions, or behaviors). A systematic review identified 6,598 potential articles from three databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO). Nine studies were eligible. A meta-analysis was problematic due to disparate interventions, outcomes, and populations. The decision to use an innovative approach that adopted the Behavior Change Technique (BCT) taxonomy to synthesize each intervention’s key features likely to be responsible for improving help-seeking was made. Of the nine studies, four were engagement strategies (i.e., brochures/documentaries), two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), two pilot RCTs, and one retrospective review. Regarding quality assessment, three were scored as “strong,” five as “moderate,” and one as “weak.” Key processes that improved help-seeking attitudes, intentions, or behaviors for men included using role models to convey information, psychoeducational material to improve mental health knowledge, assistance with recognizing and managing symptoms, active problem-solving tasks, motivating behavior change, signposting services, and, finally, content that built on positive male traits (e.g., responsibility and strength). This is the first review to use this novel approach of using BCTs to summarize and identify specific techniques that may contribute to an improvement in male help-seeking interventions, whether engagement with treatment or the intervention itself. Overall, this review summarizes previous male help-seeking interventions, informing future research/clinical developments.

Keywords: help-seeking, interventions, behavior change techniques, service utilization, mental health, men’s health, masculinity

Globally, males are 1.8 times more likely to take their own lives compared to women (Chang, Yip, & Chen, 2019; World Health Organization, 2017). This disproportionality higher suicide risk is often associated with men being less likely to seek help for mental health difficulties. Men tend to hold more negative attitudes toward the use of mental health services compared to women (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Mackenzie, Gekoski, & Knox, 2006; Möller-Leimkühler, 2002; Yousaf, Popat, & Hunter, 2015). Being male is negatively associated with one’s willingness to seek mental health support (Gonzalez, Alegría, Prihoda, Copeland, & Zeber, 2011) and is a significant predictor of help-seeking attitudes (Nam et al., 2010). These attitudes are reflected in low service use, which is consistently observed across Western countries. When controlling for prevalence rates, women in the United States are 1.6 times more likely to receive any form of mental health treatment compared to men across a 12-month period (Wang et al., 2005). Similarly, Australian women are 14% more likely to access mental health services compared to men (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007; Harris et al., 2015). Finally, the United Kingdom’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service that provides evidence-based psychological treatments for depression and anxiety receives 36% male referrals (NHS Digital, 2016). Women in the United Kingdom are also 1.58 times more likely to receive any form of treatment (either medication or psychological therapy) even when controlling for prevalence rates (McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins, & Brugha, 2016).

Although men complete more suicides globally, in Western countries the male-to-female ratio is notably higher, whereby men are 3.5 times more likely to commit suicide compared to their female counterparts (Chang et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2002). It is important to note that not all men who commit suicide have a mental health issue due to a variety of psychological, social, and physical risk factors (Turecki & Brent, 2016). However, men who do experience suicidal ideation are less likely to use mental health services (Hom, Stanley, & Jonier, 2015), reducing opportunities for prevention and intervention.

Numerous reviews have attempted to identify the pertinent factors explaining why men are more reluctant to seek help for psychological distress (Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010; Möller-Leimkühler, 2002; Seidler, Dawes, Rice, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2016). Men are thought to be deterred from engaging in mental health services due to socialization into traditional masculine gender roles. Traits associated with traditional masculinity include stereotypes of stoicism, invulnerability, and self-reliance, which are frequently discussed as they do not fit comfortably with psychological help-seeking (Tang, Oliffe, Galdas, Phinney, & Han, 2014; Vogel, Heimerdinger-Edwards, Hammer, & Hubbard, 2011). For instance, negative emotions are perceived as a sign of weakness, discouraging men from reaching out to friends (Pirkis, Spittal, Keogh, Mousaferiadis, & Currier, 2017). This negatively impacts men’s overall help-seeking behaviors and their choice of treatment type (Seidler et al., 2016). Failure to adhere to these masculine stereotypes can result in the internalization of discriminative views held by the wider public (Corrigan, Rafacz, & Rüsch, 2011; Rüsch, Angermeyer, & Corrigan, 2005). These self-stigmatizing beliefs further discourage men from seeking help (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Levant, Kamaradova, & Prasko, 2014; Pederson & Vogel, 2007).

Another explanation for poor service use relates to differences in coping strategies. Men cope with mental health difficulties differently compared to women, demonstrating an increased tendency to self-medicate with alcohol and drugs to alleviate emotional distress (Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Möller-Leimkühler, 2002; Oliver, Pearson, Coe, & Gunnell, 2005; Rutz & Rihmer, 2009). This is supported by higher prevalence rates of substance use disorders in men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004; Wilhelm, 2014). Similarly, mental health literacy (i.e., one’s knowledge of prevention, symptom recognition, and available treatments including self-help strategies) influences help-seeking (Jorm, 2012). Poor mental health literacy is reported to be associated with lower use of mental health services (Bonabi et al., 2016; Thompson, Hunt, & Issakidis, 2004). Men are regarded as having poorer mental health literacy compared to women as they are worse at identifying mental health disorders (Cotton, Wright, Harris, Jorm, & McGorry, 2006; Swami, 2014).

Another obstacle men experience is the lack of appropriate diagnostic instruments and clinician biases. Men express symptoms of depression that do not always conform to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., DSM-5; Addis, 2008; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For example, they may express more externalizing behaviors such as alcohol consumption, irritability, and aggressive behaviors while underreporting other symptoms (Angst et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2015). These factors may mask men’s difficulties, leading to inaccurate diagnoses and inappropriate treatment (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2003; Kerr & Kerr, 2001). In response to these symptomatic gender differences, it has been suggested that men would benefit from lower clinical thresholds (Angst et al., 2002) or the use of other measures that may be more sensitive to the symptoms that they express (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2003; Strömberg, Backlund, & Löfvander, 2010). Furthermore, clinicians may suffer from their own biases with the expectation that men should fulfill particular masculine stereotypes (Mahalik, Good, Tager, Levant, & Mackowiak, 2012). For example, when men do not conform to these traditional masculine stereotypes by expressing themselves emotionally or by taking responsibility for their health, they may be regarded as deviant and/or feminine (Seymour-Smith, Wetherell, & Phoenix, 2002; Vogel, Epting, & Wester, 2003). These biases influence the quality and type of care provided and leave men less likely to receive a diagnosis despite presenting with similar or identical symptoms to women (Doherty & Kartalova-O’Doherty, 2010).

Focusing on masculinity has been argued to be overly focused on problems associated with masculinity, so clinicians neglect adaptive traits. A more recent framework, “positive masculinity” (Englar-Carlson & Kiselica, 2013; Kiselica & Englar-Carlson, 2010) has suggested that masculine qualities can be valued. For example, self-reliance and responsibility can be helpful when experiencing emotional difficulties (Englar-Carlson & Kiselica, 2013; Fogarty et al., 2015). Indeed, positive masculinity and practitioner training around male gender socialization may assist with reducing practitioner biases when working with men (Mahalik et al., 2012).

It is important to note that the degree to which these characteristics occur vary between men as they are not a homogeneous group. Not all men will conform to traditional masculine norms and there are varying degrees of mental health literacy and symptom expression. In addition, other factors such as a person’s culture (Guo, Nguyen, Weiss, Ngo, & Lau, 2015; Lane & Addis, 2005), sexual orientation (Vogel et al., 2011), and severity and type of presenting symptoms (Edwards, Tinning, Brown, Boardman, & Weinman, 2007) also influence one’s willingness to seek mental health help.

The philosophies underlying interventions to improve men’s help-seeking have varied. Indeed, targeting one’s conformity to traditional masculine stereotypes may elicit behavior change that extends to psychological help-seeking in men (Barker, Ricardo, Nascimento, Olukoya, & Santos, 2010; Blazina & Marks, 2001). This approach may be perceived as aligning with feminist initiates, thus representing an antagonistic position against masculinity and male values (Hearn, 2015). Similarly, men’s health campaigns addressing topics such as male victims of domestic violence and male suicide statistics reinforce the notion that men are a victimized group. This makes them susceptible to being used to justify certain men’s rights movements seeking to regain hegemonic masculine ideals that have been previously threatened (Salter, 2016). Although many acknowledge that men and women’s health initiatives are not a binary choice (Baker, 2018), these strategies may face some resistance from the wider public. This can therefore be a complex process made inherently more difficult by the current social and political climate.

Approaches that leverage traditional masculine norms have the potential to improve service uptake; however, they also pose the risk of reinforcing masculine stereotypes (Fleming, Lee, & Dworkin, 2014; Robinson & Robertson, 2010). Campaigns such as Man Up Monday seek to encourage tests for sexually transmitted infections (Anderson, Eastman-Mueller, Henderson, & Even, 2015) but also reinforce the notion that to be a “real man” one must sleep with multiple partners and engage in violent or risky sexual behaviors (Fleming et al., 2014). Such campaigns have been criticized for reinforcing negative masculine stereotypes while undercutting alternative, positive campaigns that seek to encourage respectful and communicative sexual relationships (Fleming et al., 2014). These approaches could be argued to contribute to an increase in violence and poorer well-being among men (Baugher & Gazmararian, 2015; Courtenay, 2000).

Given the disparity in mental health service use between men and women, it is important that strategies designed to improve help-seeking among men are developed further. Limited work has been carried out to address these problems, with only a handful of public awareness campaigns and interventions designed to improve men’s psychological help-seeking. These include the Real Men. Real Depression campaign focusing on educating the public about depression in men (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d), a male-sensitive brochure to address help-seeking in depressed men (Hammer & Vogel, 2010), an intervention aiming to reduce self-stigma associated with mental health problems (MacInnes & Lewis, 2008), the HeadsUpGuys website that provides information and management tips for depression to encourage men to seek help (Ogrondniczuk, Oliffe, & Beharry, 2018), and Man Therapy, a program designed to teach men about mental health and self-evaluation tools that encourage them to engage in treatment (Spencer-Thomas, Hindman, & Conrad, 2014).

Such initiatives, particularly campaigns, are often not rigorously tested to see if they do significantly improve psychological help-seeking (attitudes, intentions, or behaviors) compared to controls or preexisting strategies that are not gender specific. Moreover, they appear to be constructed in isolation with limited collaboration between researchers who share the same goal. When developing a complex intervention, it is recommended that a theoretical understanding of the likely processes eliciting behavior change be explored (Craig et al., 2008). However, many initiatives do not explore these processes in detail, making it difficult to develop more effective interventions that improve help-seeking.

This review aims to collate and synthesize previous interventions that have been designed to improve psychological help-seeking in men. Additionally, this review seeks to identify key components across these interventions that are likely to contribute to improvements in help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and/or behaviors. These key components can then be used as a theoretical framework within which to develop future mental health help-seeking approaches for men. This review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Prisma Group, 2009) and was preregistered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=82270).

Method

Search Strategy

Published interventions measuring help-seeking behaviors were identified from the electronic databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. A comprehensive review was conducted on March 1, 2019, without any restrictions on publication year, language, or method. The search strategy was first formulated for Ovid (MEDLINE) before being adapted for other databases. Subject headings of terms related to “help-seeking” OR “barrier” AND terms related to “mental health”, “intervention” AND “male sex” were used (see Supplementary Appendix 1). Furthermore, publications identified from manual reference checks were also included to ensure a comprehensive search strategy.

Population

As highlighted previously, men’s help-seeking behaviors differ significantly from those of women, thus requiring different techniques and strategies to engage them. To ensure that the current review’s findings would be applicable to men specifically, only interventions containing a 100% male sample or studies with a male subanalysis were included. Both community and clinical populations were eligible. Community populations referred to interventions that did not record or screen out by mental health status of their recruited sample. For interventions including a clinical population, mental health diagnosis was confirmed by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD; World Health Organization, 1992) or DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), or which met clinical cutoffs on validated scales used to measure mental health severity and/or symptoms. Criminal and prison populations were excluded, as barriers and routes to mental health care will be notably different from nonprison populations, such as court-ordered treatments and treatment eligibility (Begun, Early, & Hodge, 2016). Similarly, participants under the age of 18 years were excluded from the present review, as younger populations have additional facilitators to mental health care such as parental and school support (Dunne, Bishop, Avery, & Darcy, 2017). Younger boys also have access to child and adolescent mental health services, which often have different assessment criteria and available treatments (Singh & Toumainen, 2015), potentially influencing help-seeking.

Interventions

All interventions measuring changes to help-seeking as a primary, secondary, or additional outcome measure were included. Help-seeking behaviors were defined as changes to help-seeking attitudes (i.e., the beliefs held toward seeking professional help when faced with a serious emotional/mental health problem); intentions (i.e., one’s willingness/readiness to seek support); or practical help-seeking (i.e., inquiring or presenting to professional psychological services or reaching out for social support from friends or family). For the remainder of this review, changes to help-seeking refer to changes in attitudes, intentions, or behaviors.

Eligible Articles

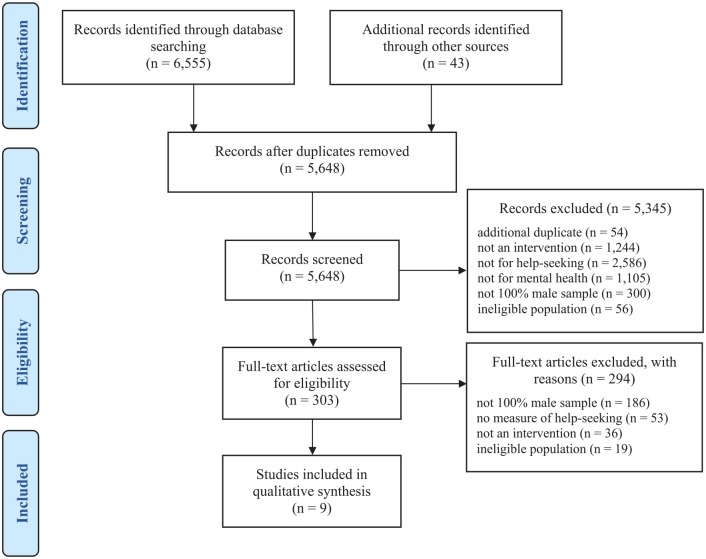

In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, the study selection was undertaken in two phases (Moher et al., 2009). After identification and removal of duplicates, all articles were screened via the title and abstract by the first author (ISO). Two authors (ISO and LB) retrieved and screened the full text of those articles selected after phase 1. From the 6,598 articles identified, 9 reports met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A Cohen’s kappa (κ) statistic was calculated to assess the interrater reliability, whereby ≤0 indicates no agreement, 0.01–0.20, slight, 0.21–0.40, fair, 0.41–0.60, moderate, 0.61–0.80, substantial, and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect levels of agreement (Cohen, 1960; McHugh, 2012). A substantial level of agreement was achieved between the two authors (ISO and LB), κ = 0.73. Subsequently, both authors (ISO and LB) resolved discrepancies by referring to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Where disagreements remained, a third author was consulted for a deciding opinion (JB). Thus, 100% consensus was obtained.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Quality Assessment

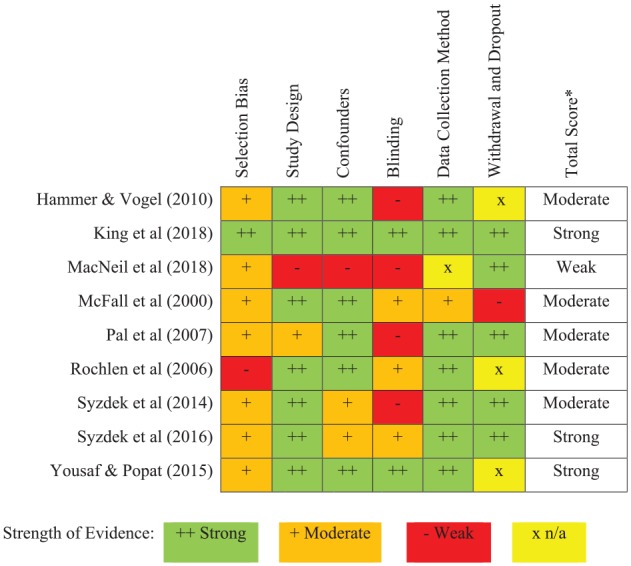

The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) checklist was used to assess the quality of each study (Thomas, 2003). Initially, preregistration stated that the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, n.d.) checklist would be used; however, no qualitative studies were eligible. The EPHPP has been recommended when assessing the quality of public health interventions, particularly for those with varying experimental designs (Deeks et al., 2003; Jackson & Waters, 2005). The EPHPP has also been reported to have better interrater reliability than the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (Armijo-Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo, & Cummings, 2012). Six components of the study’s methodology (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawal and dropouts) were scored as either weak, moderate, or strong to reach an overall quality rating, also coded as weak, moderate, or strong (Figure 2). An overall score of strong was assigned when there were no weak ratings, moderate for one weak rating, and weak if there were two or more weak ratings. The quality assessment was conducted by two authors (ISO and LB), scoring a substantial level of agreement, κ = 0.80. Similarly, all disagreements were discussed to reach 100% consensus.

Figure 2.

The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) checklist criteria for each study. *Total scores were calculated as strong where 0 weak rating, moderate where 1 weak rating, and weak where ≥ 2 weak ratings were scored.

Data Extraction

Data extraction consisted of country of study, number of participants, age of participants, type of population, diagnosis of population, study design, the intervention’s characteristics, and outcome measures (Table 1). Additional information regarding uptake and dropout for the interventions was also included (see Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Table Summarizing Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Author (year) | Country | N | Mean age in years (SD) | Population | Diagnosis (measure) | Design | Intervention aim | Intervention type and length | Intervention delivered by | Help-seeking outcome measures | Other outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hammer and Vogel (2010) | United States | 1,397 | 29.44 (10.19) | Depressed community sample | Depression (CES-D) |

RCT | Compare a newly developed male-sensitive brochure to a gender-neutral brochure | Male sensitive brochure vs. RMRD brochure vs. gender neutral brochure | Brochure | ATSPPHS (short version) | Self-stigma of seeking help |

| King et al. (2018) | Australia | 354 | 38.80 (19.9) | Community | N/A | Double-blind RCT | If the Man Up documentary could increase help-seeking intentions | Three-part documentary (1 hr per part) examining the link between masculinity and mental health vs. control | Video documentary | The General Help-Seeking Questionnaire | CMNI, GRCS, social support, well-being, resilience, and ASIQ |

| MacNeil et al. (2018) | Canada | 14 | 28.21 (8.04) | Clinical | Eating disorder (DSM-5) | Retrospective review | To examine male referral rates across TAU and MATT | Male-sensitive assessment and treatment track vs. ATAU | Outpatient eating disorder clinical team | Referral rates to MATT | SWLS, BDI, BAI, EDI-3 |

| McFall et al. (2000) | United States | 594 | 51.05 (3.75) | Clinical | PTSD (compensation receipt for veterans) |

RCT | Assess whether an outreach intervention providing information about services would improve service enrolment | Outreach PTSD information brochure + 1-month follow-up call vs. control | Leaflets and the study coordinator | Treatment inquiries. Agreement and/or attendance to a mental health provider | N/A |

| Pal et al. (2007) | India | 90 | 29.70 (9.89) | Clinical | Treatment nonattendance and problematic drinking (AUDIT) | RCT | Examine change in alcohol use following a brief intervention compared to simple advice | Two 45-min sessions of brief motivational interviewing vs. control | Medical social service officer | Readiness to Change Questionnaire | WHO Quality of Life and Addiction Severity Index |

| Rochlen et al. (2006) | United States | 209 | 21.01 (1.56) | Community | N/A | RCT | Compare men’s response to the RMRD brochure to a gender-neutral brochure | RMRD brochure vs. adapted RPRD gender-neutral brochure vs. gender-neutral mental health brochure—“Beyond Sadness” | Brochures | ATSPPHS | GRCS, MHAES, and qualitative assessments |

| Syzdek et al. (2014) | United States | 23 | 37.65 (11.44) | Depressed or anxious community sample | Anxiety and depression (DUKE-AD) | Pilot RCT | What are the effects of GBMI on mental health functioning, stigma toward internalizing disorders and help-seeking | One 2-hr GBMI vs. control | N/A | ATSPPHS and Help-Seeking Behavior Scale | AUDIT, BAI, BDI, PPL, and symptom distress |

| Syzdek et al. (2016) | United States | 35 | 19.71 (1.42) | Depressed or anxious community sample | Anxiety and depression (DUKE-AD) | Pilot RCT | Assess GBMI effect on psychosocial barriers to help-seeking | One 2-hr GBMI vs. control | Trained male graduates | Help-Seeking Behavior Scale | BAI and the treatment evaluation inventory |

| Yousaf and Popat (2015) | United Kingdom | 69 | 35.30 (12.08) | Community | N/A | Double-blind RCT | Test whether conceptual priming could increase men’s attitudes toward seeking psychological support | 25-min test—unscramble 18 sentences with priming words toward help-seeking | Scrambled sentence test | Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services | N/A |

Note. ASIQ = Adult Suicide Ideation Questionnaire; ATAU = Assessment and Treatment as Usual; ATSPPHS = Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Depression Scale; CMNI = Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; DUKE-AD = DUKE Anxiety and Depression subscale; EDI-3 = Eating Disorders Inventory 3rd edition; GBMI = Gender-Based Motivational Interviewing; GRCS = Gender Role Conflict Scale; MATT = Male Assessment and Treatment Track; MHAES = Mental Health Advert Effectiveness Scale; N/A = data not available; PPL = Perceptions of Problems in Living questionnaire; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RMRD = Real Men. Real Depression brochure; RPRD = Real People Real Depression brochure; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; TAU = Treatment As Usual; WHO, World Health Organization.

Across the nine studies identified, populations were heterogeneous with differing presenting problems (e.g., depression, problematic drinking, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], eating disorders, and a community sample). The interventions varied considerably. For instance, four promoted service engagement through the use of a brochure (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; McFall, Malte, Fontana, & Rosenheck, 2000; Rochlen, McKelley, & Pituch, 2006) or a documentary (King, Schlichthorst, Spittal, Phelps, & Pirkis, 2018), one evaluated multiple outcomes including readiness to change (Pal, Yadav, Mehta, & Mohan, 2007), one assessed the effects of priming men’s attitudes toward help-seeking (Yousaf & Popat, 2015), and three evaluated the acceptability and efficacy for improving help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and practical help-seeking (MacNeil, Hudson, & Leung, 2018; Syzdek, Addis, Green, Whorley, & Berger, 2014; Syzdek, Green, Lindgren, & Addis, 2016). As a result, a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate as results would not be meaningful, particularly as they could not be interpreted in any specific context (Higgins & Green, 2005). An alternate, novel method that identified the BCTs within interventions was used. This helped identify each intervention’s key elements that may have contributed to changes in help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and/or behaviors.

Behavior Change Techniques

BCTs refer to the observable and replicable components within an intervention designed to change behavior (Michie et al., 2013), in this case, help-seeking. BCTs represent the smallest identifiable components that in themselves have the potential to change behavior (Michie, Johnston, & Carey, 2016; Michie, West, Sheals, & Godinho, 2018). These components are referred to as the “active ingredients,” helping to make greater sense of the often very complex behavior change interventions (Michie et al., 2013). Standardization of BCTs allows for greater replicability, synthesis, and interpretation of an intervention’s specific elements that may elicit behavior change (Cane, Richardson, Johnston, Ladha, & Michie, 2015; Michie et al., 2013).

Michie et al. (2013) devised a taxonomy (BCCTv1) containing 93 BCTs to address the lack of consistency and consensus when reporting an intervention (Craig et al., 2008). Examples of BCTs include framing/reframing whereby a new perspective on a behavior is suggested to change emotions or cognitions, re-attribution defined as suggesting alternative explanations to the perceived cause of the behavior, and credible source, which involves the presentation of verbal or visual information by a credible source, such as celebrity figures, mental health professionals, and/or other men with lived experiences of mental health, either in favor of or against the behavior.

For the current review, each intervention’s BCTs were independently coded by two authors (ISO and LM) trained in recognizing and coding BCTs (http://www.bct-taxonomy.com/). These were then discussed to reach consensus and are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Table Summarizing the Identified Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) and Outcomes of Eligible Interventions.

| Author | Identified BCTs | Help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and behaviors (p, d) | Symptoms (p, d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement strategies (brochures/documentary) | |||

| Hammer and Vogel (2010) | 5.3. Information about social and environmental

consequences 5.6. Information about emotional consequences 6.2. Social comparison 9.1. Credible source |

Improved attitudes to help-seeking (p < .05*, d = n/a) | Not measured |

| King et al. (2018) | 5.6. Information about emotional consequences 6.1. Demonstration of the behavior 6.2. Social comparison 9.1. Credible source 16.3. Vicarious consequences |

Improved help-seeking intentions and intentions to seek help from male and female friends (p < .05*, d < .05) | No changes in suicidal ideation (p > .05) |

| McFall et al. (2000) | 3.1. Social support (unspecified) 4.1. Instruction on how to perform a behavior 9.1. Credible source |

Improved service enquiry, attendance, and follow-up appointments (p < .05*, d > .05) | Not measured |

| Rochlen et al. (2006) a | 4.1. Instruction on how to perform a behavior 5.6. Information about emotional consequences 6.2. Social comparison 9.1. Credible source |

Male-sensitive and gender-neutral brochures both improved help-seeking attitudes (p < .05*, d = n/a) | Not measured |

| Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | |||

| Pal et al. (2007) | 1.2. Problem solving 3.3. Social support (emotional) 5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences 8.2. Behavior substitution 11.2. Reduce negative emotions 15.1. Verbal persuasion about capability |

Improved readiness to change (i.e., intentions) from baseline to 1-month follow-up (p < .05*, d = n/a) | Reduced alcohol addiction severity, reduced alcohol use in past 30 days, and improved psychological and physical well-being (p < .05* for all) |

| Yousaf and Popat (2015) | None identified | Higher attitudes towards seeking mental health services for the primed group vs. control (p < .05*, d > .5) | Not measured |

| Syzdek et al. (2014) | 2.2. Feedback on behavior 2.7. Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior 3.3. Social support (emotional) 4.1. Instruction on how to perform a behavior |

No changes in help-seeking attitudes or help-seeking intentions (p > .05, d < .5) | Reduction in anxiety (p > .05, d < .5), depression (p > .05, d < .5), and problematic drinking (p > .05, d > .5) |

| Syzdek et al. (2016) | 1.4. Action planning 2.2. Feedback on behavior 2.7. Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior 3.3. Social support (emotional) 4.3. Re-attribution 5.6. Information about emotional consequences 9.1. Credible source 13.2. Framing/reframing |

Increased behavioral help-seeking from parents, (p < .05*, d > .5), professionals, (p > .05, d > .5), partners, (p > .05, d > .5), friends, (p > .05, d > .5), and counseling services (p > .05, d > .5) | No change in depression (p > .05, d < .5) or anxiety (p > .05, d < .5) |

| Retrospective review | |||

| MacNeil et al. (2018) | 3.3. Social support (emotional) 5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6. Information about emotional consequences 6.2. Social comparison |

Received more male referrals after the instalment of intervention (MATT) (p < .05*, d < .05) | Not measured |

Note. aOne study reported their effect size in partial eta-squared and it was not appropriate to convert to Cohen’s D. d = Cohen’s D.

= p < .05.

Results

Strength of Evidence

There was a substantial level of agreement between the two authors (ISO and LB) completing the EPHPP quality assessment (Thomas, 2003; κ = 0.80). Of the nine studies included, three were scored as having “strong” quality (King et al., 2018; Syzdek et al., 2016; Yousaf & Popat, 2015), while five were deemed “moderate” in quality (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; McFall et al., 2000; Pal et al., 2007; Rochlen et al., 2006; Syzdek et al., 2014). One study was scored as having “weak” quality (MacNeil et al., 2018; Figure 2).

Categorization of Interventions

As there were different types of interventions with some aiming to engage men (e.g., brochures/video documentary) and other interventions aiming to change behavior or attitudes, the interventions were divided into three main categories of “engagement strategies,” “RCTs/pilot RCTs,” and “retrospective reviews.”

Engagement strategies comprised of three interventions delivering a brochure (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; McFall et al., 2000; Rochlen et al., 2006) and one study delivering a three-part video documentary (King et al., 2018) to improve help-seeking. RCTs/pilot RCTs included two RCTs (Pal et al., 2007; Yousaf & Popat, 2015) and two pilot RCTs (Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016). The last intervention was a retrospective review comparing referral rates before and after the instalment of a male-sensitive assessment and treatment program (MacNeil et al., 2018).

A summary of the specific elements or BCTs used across all the interventions that may have contributed to improvements in male help-seeking are given in Table 3. The engagement strategies (i.e., brochures/documentary, n = 4) and retrospective review (n = 1) contained eight and four BCTs, respectively. Fourteen BCTs were identified within the RCTs/pilot RCTs (n = 4). As six BCTs (3.3, 4.1, 5.3, 5.6, 6.2, and 9.1) were coded across the different intervention categories (i.e., engagement strategies, RCTs/Pilot RCTs, and retrospective review) they were only counted once, resulting in a total of 18 different BCTs across all the interventions identified.

Table 3.

Examples and Frequency of BCTs Used Within the Engagement Strategies, RCTs/Pilot RCTs, and Retrospective Review.

| BCT | BCT example(s) | BCT frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement strategies (brochures/documentary) | ||

| 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | Telephone survey that provided an opportunity to ask questions about services, schedule an appointment, and address perceived barriers. (McFall et al., 2000) | 1 |

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behavior | Option to receive information about services and how to schedule an intake appointment/description of treatment options (McFall et al., 2000; Rochlen et al., 2006) | 2 |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | Description of mental health symptoms through the use of male-sensitive language (Hammer & Vogel, 2010) | 1 |

| 5.6 Information about emotional consequences | Brochure containing facts specific to men and depression (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; Rochlen et al., 2006) and a documentary delivering psychoeducational material about mental disorders (King et al., 2018) | 3 |

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior | Video featuring men modeling positive health behaviors such as emotional expression and seeking help (King et al., 2018) | 1 |

| 6.2 Social comparison | Testimonials and photographs of men who have experienced depression (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; Rochlen et al., 2006) and a show host talking to other men who have reached out for help (King et al., 2018) | 3 |

| 9.1 Credible source | Letter from the program director inviting men to seek care (McFall et al., 2000), testimonials of men who have experienced depression (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; Rochlen et al., 2006), and information being delivered by a familiar radio and television host (King et al., 2018) | 4 |

| 16.3 Vicarious consequences | Other men talking about how reaching out for help changed their mental health trajectory for the better (King et al., 2018) | 1 |

| RCTs and pilot RCTs | ||

| 1.2 Problem solving | Prompting discussion of drinking alternatives, high-risk situations, and coping without alcohol (Pal et al., 2007) | 1 |

| 1.4 Action planning | Developing an action plan on how to improve mental health, which may include seeking help (Syzdek et al., 2016) | 1 |

| 2.2 Feedback on behavior | A feedback report outlining personal scores on symptom measures (Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016) | 2 |

| 2.7 Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior | Feedback on symptom levels and untreated mental health (Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016) | 2 |

| 3.3 Social support (emotional) | Adopting a motivational interviewing framework or a gender-based motivational interviewing framework (Pal et al., 2007; Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016) | 3 |

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behavior | Discussing different actions that could be taken to address mental health problems such as formal help, informal help, and coping skills (Syzdek et al., 2014) | 1 |

| 4.3 Re-attribution | Elicited how participants untreated mental health may be affecting their value-driven behaviors (Syzdek et al., 2016) | 1 |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | Information regarding the harmful consequences of drinking. Linking alcohol consumption to potential consequences (Pal et al., 2007) | 1 |

| 5.6 Information about emotional consequences | Providing psychoeducational material about mental disorders (Syzdek et al., 2016) | 1 |

| 8.2 Behavior substitution | Exploration of alternatives to drinking alcohol (Pal et al., 2007) | 1 |

| 9.1 Credible source | Listing famous men with internalizing disorders (Syzdek et al., 2016) | 1 |

| 11.2 Reduce negative emotions | Reducing stress related to personal responsibility (Pal et al., 2007) | 1 |

| 13.2 Framing/reframing | Reframing help-seeking to be consistent with participants’ values and masculine norms (Syzdek et al., 2016) | 1 |

| 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | Emphasis on participants responsibility to change, facilitating self-efficacy and optimism (Pal et al., 2007) | 1 |

| Retrospective review | ||

| 3.3 Social support (emotional) | Delivering cognitive behavioral therapy (MacNeil et al., 2018) | 1 |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | Providing psychoeducation and the biological model of mental health illnesses (MacNeil et al., 2018) | 1 |

| 5.6 Information about emotional consequences | Discussing the negative impact mental health has on daily living, relationships, and sport (MacNeil et al., 2018) | 1 |

| 6.2 Social comparison | Highlighting that the men are not alone with their mental health struggles and that there are others experiencing the same (MacNeil et al., 2018) | 1 |

Note. BCT = behavior change technique; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

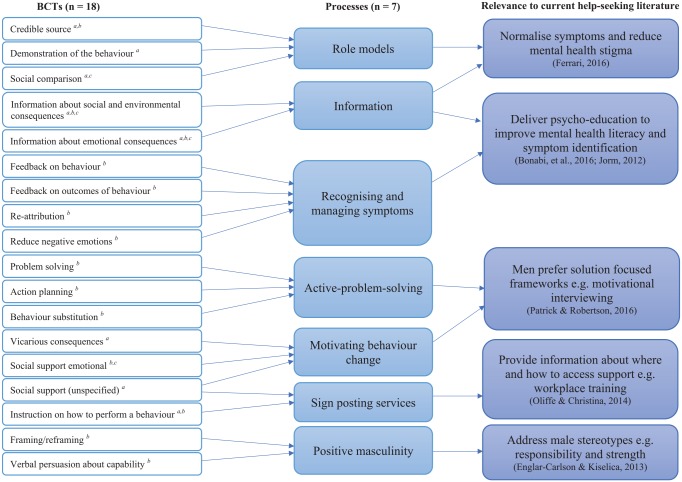

The BCTs identified from the engagement strategies, RCTs/pilot RCTs, and retrospective review were analyzed separately due to different behavior change approaches (Table 3). Various BCTs were grouped into “processes” to help synthesize the 18 distinct techniques implemented across these dissimilar interventions. These processes can be seen as overarching terms that summarize similar BCTs into broader psychological processes, thus helping to bridge the gap between these research findings and wider clinical practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of behavior change techniques (BCTs) into processes and their relevance to the current literature. aBCT identified within engagement strategies. bBCT identified within randomized controlled trials (RCTs)/pilot RCTs. cBCT identified within retrospective review.

BCTs Within the Engagement Strategies

The most commonly used BCTs within the engagement strategies (i.e., brochures/video documentary) used a “credible source” and provided “information about the consequences” (either emotional, social, or environmental) of poor mental health. Testimonials and photographs of men with depression (i.e., credible source) were used to explain a medical model of depression and the associated symptoms (i.e., information). Similarly, a familiar radio/television host was used to deliver mental health information (King et al., 2018). Video footage of men talking about their personal problems, help-seeking, and emotional expression was also used to model positive health behaviors and demonstrate how to seek help (King et al., 2018). These highlighted the “social comparison” BCT as it provided someone who one could relate to (Hammer & Vogel, 2010; King et al., 2018; Rochlen et al., 2006). Similarly, Rochlen et al. (2006) used testimonials and photographs of men in their male-sensitive brochure who had experienced depression. This may have contributed to an improvement in help-seeking attitudes among men, despite not showing larger improvements compared to a gender-neutral brochure (Rochlen et al., 2006). Finally, McFall et al.’s (2000) intervention implemented a “credible source” (i.e., a letter from the PTSD program director encouraging veterans to seek care), contributing to an improvement in practical help-seeking. In sum, all four engagement strategies utilized a role model (i.e., credible source BCT), which may have contributed to an improvement in help-seeking.

In addition to the processes of providing information and using role models, the BCTs of “instruction on how to perform a behavior” and “unspecified social support” were used. Here, men received a telephone call to discuss the brochure before explaining how to schedule an appointment with a mental health service (McFall et al., 2000).

Brochures appeared to be an effective strategy to improve men’s help-seeking behaviors. The processes of using role models and delivering information about the long-term outcomes of mental health disorders, symptoms, and potential services appeared to help elicit this behavior change.

BCTs Within RCTs and Retrospective Review

The RCTs and pilot RCTs also made use of role models (i.e., credible source BCT). Famous men with depression or anxiety were listed to challenge misconceptions of mental health (Syzdek et al., 2016). Again, these methods provided real-life examples of other men experiencing the same or similar difficulties eliciting a sense of social comparison (MacNeil et al., 2018). The interventions that provided information about the emotional, social, and environmental consequences of mental illness appeared to improve help-seeking, whether behaviorally or attitudinally. The interventions included psychoeducational materials about mental disorders (Syzdek et al., 2016), addressed the consequences of alcohol consumption (Pal et al., 2007), and/or explored how eating disorders impact daily living, relationships, and sport (MacNeil et al., 2018).

Alongside providing information and using role models, several other processes were identified. A process helping men to recognize and manage their symptoms was also identified. This contained the BCTs of “feedback on behavior,” “feedback on outcomes of behavior(s),” “re-attribution,” and “reduce negative emotions.” Syzdek and colleagues gave feedback on participants’ current difficulties identified from a computerized assessment, before exploring whether their untreated mental health was affecting their value-driven behaviors (Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016). This enabled men to re-attribute their current symptoms to their behaviors. Moreover, the intervention by Pal et al. (2007) helped reduce stress associated with problematic drinking in an Indian context.

Second, a process incorporating active problem-solving exercises was identified. This contained the BCTs of “problem solving,” “behavior substitution,” and “action planning.” These involved planning how to improve one’s mental health through seeking professional or nonprofessional help (Syzdek et al., 2016), discussing situational drinking cues, and exploring alternative drinking activities for hazardous drinkers (Pal et al., 2007), respectively.

“Emotional social support,” “instruction on how to perform a behavior,” and “vicarious consequences” were other BCTs that were identified. These contributed to two processes of motivating behavior change and signposting services.

The motivating behavior change process comprised of the “vicarious consequences” and “emotional social support” BCTs as the BCCTv1 dictates that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing (MI) frameworks should be coded as emotional social support (Michie et al., 2013). This BCT was observed in two studies using CBT and MI (MacNeil et al., 2018; Pal et al., 2007) and two pilot RCTs adapting MI to be gender sensitive (Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016). Also, the BCT of “vicarious consequences” was used within one engagement strategy, whereby men with lived experience discussed how seeking mental health help improved their overall trajectory (King et al., 2018). As a result, it appears that the BCTs of “emotional social support” and “vicarious consequences” motivated men to change their behaviors related to their mental health.

For the signposting services process, men were provided with a brochure listing their university’s counseling services and referral information for community mental health providers (i.e., “instruction on how to perform a behavior” BCT; Syzdek et al., 2016). Syzdek and colleagues also discussed potential actions that could be taken to address men’s current mental health problems including formal help, informal help, and coping skills (Syzdek et al., 2014).

Finally, the process of positive masculinity included the BCTs of “framing/reframing” and “verbal persuasion about capability,” noted across two interventions. Here, help-seeking was reframed to be consistent with current masculine norms (i.e., a sign of strength; Syzdek et al., 2016) and emphasis was placed on one’s personal responsibility to change (Pal et al., 2007).

In summary, various BCTs were used within the interventions. This enabled the identification and synthesis of different processes that contribute to positive help-seeking behaviors. The use of role models and information was important for the engagement strategies (i.e., brochures/documentary). This was further supplemented by instructions on how to seek help and social support. These processes were also apparent in the RCTs and the retrospective review. Additional processes included active problem solving, recognizing and managing symptoms, signposting services, motivating behavior change, and building on positive masculine traits (e.g., responsibility and strength; Figure 3). It is suspected that these processes contributed to the improvements in help-seeking.

Discussion

As mentioned previously, distinct BCTs were grouped into “processes” to enable these research findings to be more relevant in a clinical context. Seven key processes were synthesized from the 18 identified BCTs. These included using role models to convey information, psychoeducational material to improve mental health knowledge, assistance with recognizing and managing symptoms, active problem-solving tasks, motivating behavior change, signposting services, and incorporating content that builds on positive male traits (e.g., responsibility and strength).

To understand these processes in greater detail, the current male help-seeking literature was used to help explain why these processes may have contributed to an improvement in psychological help-seeking by men from the studies identified within this review.

Interpretation of BCTs With Regard to the Literature

Despite the heterogeneity across interventions, the 18 identified BCTs had a fairly consistent overlap with key constructs that have already been identified within the help-seeking literature. The process of delivering information about the emotional, social, and environmental consequences of help-seeking and/or mental health diagnoses can be seen as a facet of mental health literacy. Indeed, poor mental health literacy is a barrier to help-seeking (Bonabi et al., 2016) and having knowledge of mental health disorders assists in their recognition, management, and prevention (Jorm, 2012).

Using role models and supporting men to recognize and manage their symptoms were also of importance. This was helpful as role models often normalized the problems, offering reassurance that the difficulties were the result of everyday stressors. This made the problems more acceptable, enabling men to acknowledge their symptoms, and may have reduced mental health stigma (Ferrari, 2016). This can also help model the behavior of seeking help when experiencing psychological distress. There is a danger that if not carefully used, this could also increase self-stigmatizing beliefs about mental health. Once men identify with having a mental health problem, they may criticize themselves for not being able to cope or fear that they will be judged for having a mental health condition (Primack, Addis, Syzdek, & Miller, 2010). These stigmatizing beliefs may deter men from seeking help. Nevertheless, improving mental health literacy and using role models supported men to identify their own symptoms before discussing them in a safe setting. This helped to preserve their autonomy and clarify whether their symptoms required professional support. Considering this, some men may prefer a person-centered approach as they may feel discouraged from engaging in treatment that seeks to label a mental health diagnosis in a clinical framework (River, 2018). Although this may not improve treatment outcomes, it may improve service uptake. However, this has not been formally assessed.

Processes using active problem-solving exercises and motivating behavior change also seemed important across the interventions in this review. Men were provided with specific information about how to improve their mental health and use a variety of management strategies. Interventions that implement an action-orientated or solution-focused framework may be promising as men are less inclined to engage in traditional talking therapies (Patrick & Robertson, 2016). This was also demonstrated from three interventions adopting an MI framework (Pal et al., 2007; Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016). Similarly, drawing men’s attention to the potential benefits of treatment and how seeking help can improve long-term outcomes may also improve their motivation to seek help (King et al., 2018). The process of signposting must not be overlooked. This process informed men about where and how to access professional support, indicating that men may need more guidance on this. Workplace training and the development of bridging services could help connect and motivate men to engage with existing mental health services (Oliffe & Christina, 2014).

An equally important process that built on positive masculine traits emerged from two interventions (Pal et al., 2007; Syzdek et al., 2016). Targeting adaptive masculine stereotypes, such as responsibility, and reframing help-seeking to align with male values (e.g., a sign of strength) may have contributed to an improvement in help-seeking behaviors. This process fits in with Englar-Carlson and Kiselica’s work on “positive masculinity” (2013), which acknowledges the virtues of masculinity, as opposed to remedying weaknesses (Kiselica & Englar-Carlson, 2010). This motivated men to take responsibility in looking after themselves and emphasized that seeking help for mental health difficulties does not indicate weakness, nor is it detrimental to one’s masculinity.

Implications for Future Research

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review to identify key features within an intervention that may contribute to an improvement in help-seeking for men. A post hoc decision to use the BCCTv1 to analyze and synthesize these interventions using BCTs was made because of the idiosyncratic nature of this research field, but it has proved very successful.

Other public health interventions or fields that lack consensus or have limited data may find this approach useful when synthesizing diverse interventions. Moreover, identifying promising BCTs is a good way forward when trying to understand or design interventions targeting a behavior. Although the full BCCTv1 contains 93 BCTs (Michie et al., 2013), the current review only identified 18 different BCTs. Thus, future research is needed to understand these promising 18 BCTs in more detail and to prevent overlooking other, potentially effective techniques.

To promote more coherent evidence, it is advised that a standardized reporting method is adopted when reporting newly developed help-seeking interventions for men. For example, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (Hoffman et al., 2014), the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement (Des Jarlais, Lyles, Crepaz, & Trend Group, 2004), and the use of BCCTv1 will improve the clarity and consistency in this field. Alternatively, the development of a new male-specific framework for reporting help-seeking interventions would be helpful. Such a framework should place emphasis on the initial uptake to an intervention, the intervention’s main components (i.e., BCTs), and the strategies used to recruit men (such as marketing techniques, language, and phrases chosen) as these have been highlighted as key factors when designing male interventions (Pollard, 2016).

Ideally, future work would seek to evaluate the role specific BCTs have in changing help-seeking behaviors. Eventually, the evidence base would point toward specific techniques that are more effective than others. This enables better tailoring of interventions that address men’s needs. This could also transpire into further precision tailoring for various subgroups of men, as help-seeking differs across ethnicities (Parent, Hammer, Bradstreet, Schwartz, & Jobe, 2018), education levels (Hammer, Vogel, & Heimerdinger-Edwards, 2013), and conformity to masculine norms (Wong, Ho, Wang, & Miller, 2017). Similarly, if it is possible to identify redundant or ineffective techniques within interventions, more cost-effective solutions can be developed. As more male-focused interventions addressing psychological help-seeking are designed, work can be done to dismantle and identify the effective techniques within them.

Implications for Clinical Practice

All four engagement strategies utilizing brochures and documentaries demonstrated significant improvements in help-seeking. Brochures and documentaries may therefore be a feasible and acceptable strategy to enable behavior change in men. This suggests men may not need direct face-to-face contact and are receptive to less invasive and personal strategies. This was further demonstrated through a conceptual priming task that improved help-seeking attitudes (Yousaf & Popat, 2015).

Mental health literacy can be a strong facilitator for seeking mental health help (Bonabi et al., 2016). When given a vignette, men are less likely to identify other men as having a mental health difficulty (Swami, 2014). Moreover, poor identification of depressive symptoms and inadequate suggestions to treatment (e.g., do nothing and leave them alone) are associated with being male (Kaneko & Motohashi, 2007). This demonstrates that, generally, men have inaccurate perceptions of their health and are poorer at recognizing symptoms.

Psychoeducational materials may help men to understand their current difficulties and the possible long-term outcomes of mental health conditions. This may enable men to distinguish their symptoms from everyday stressors, eliciting a greater perceived need for help. Although psychoeducational materials may contribute to favorable help-seeking attitudes, they need to be carefully delivered (Gonzalez, Tinsley, & Kreuder, 2002). Men who do identify as having a mental health difficulty are at risk of stigmatizing themselves for not being “strong enough” to cope (Primack et al., 2010), reducing their likeliness of seeking support. To overcome this, such information should be delivered in a supportive manner to help men accept their difficulties without feeling a sense of shame or loss of autonomy (Johnson, Oliffe, Kelly, Galdas, & Ogrodniczuk, 2012). This should be combined with offering reassurance about where they can access professional support and treatment information and signposting appropriate services. Once in treatment, interventions that steer away from a diagnostic framework may be more palatable to men (River, 2018). They should aim to provide men with skills and greater self-control as opposed to treating what is wrong with them. This has been demonstrated through interventions marketed as “improve your sleep” or a “stress workshop,” gaining high levels of male engagement (Archer et al., 2009; Primack et al., 2010). Also, using male role models such as celebrities and others with mental health difficulties may particularly appeal to men, helping to reduce mental health stigma and improve service uptake.

Finally, active problem-solving or tangible solution-focused approaches have been reported to be effective for changing other behaviors, such as increasing physical activity and dieting (Hunt et al., 2014). Indeed, such approaches might be more appealing to men.

These are not the entirety of processes that will improve male help-seeking. Similarly, working outside a diagnostic framework, providing men with skills that offer greater self-control and adopting solution-focused approaches are not definitive solutions, as what may be helpful for some men may not be for others. Nonetheless, these techniques demonstrate some potential for improving help-seeking in men and may continue to be effective.

Strengths and Limitations

This review has established how to synthesize complex behavioral interventions across different types of interventions. The steps taken to identify the active ingredients responsible for behavior change have been demonstrated. A strength of this review included the use of a validated taxonomy used in other areas with reasonable interrater reliability (Michie et al., 2013). All interventions were coded through consensus by two authors (ISO and LM). The current review has pointed out the specific techniques that should be considered when developing male help-seeking interventions in the future. This review has also implemented a systematic approach that utilized two reviewers throughout, resolved discrepancies to reach consensus, and adopted a comprehensive search strategy.

There are however some limitations. Although the BCTTv1 is a widely used approach identifying techniques that elicit behavior change, it is not possible to guarantee 100% accuracy of the coded BCTs, as they do not have perfect interrater reliability. This is further confounded as it is likely that an intervention’s true content is underreported (Michie, Fixsen, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2009). The recorded BCTs were only identified from the description provided in the published articles. It would therefore be helpful if future interventions reported their content more fully, ideally using BCTs or a similar system.

The BCT taxonomy also presents other limitations. For instance, the BCTTv1 states that “emotional social support” extends to MI and CBT (Michie et al., 2013). This is a limitation for the interpretation of the current findings as MI was implemented within three studies in this review (Pal et al., 2007; Syzdek et al., 2014, 2016). Indeed, MI includes aspects of emotional support, but in addition, behavior change elicited from MI is thought to arise through combating ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Ambivalence refers to the experience of motivations for and against a behavior. Thus, a MI framework seeks to elicit the positive reasons for changing a behavior (Miller & Rose, 2015). In this context, emotional support may not necessarily have contributed to improvements in help-seeking per se, but men may need to work through their motivations both for and against seeking psychological support in order to improve their help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and/or behaviors. The BCT taxonomy does not allow us to determine whether emotional support or working through ambivalence contributes to changes in help-seeking. A suggestion to overcome this limitation would be to use another taxonomy that seeks to identify specific MI techniques that contribute to behavior change (Hardcastle, Fortier, Blake, & Hagger, 2017). Indeed, this may enable the distinction between social support and combating ambivalence.

Although help-seeking is consistently reported to be worse in males (Mackenzie et al., 2006), the identified techniques in this review should be interpreted cautiously. Men are not a homogeneous group. Alongside sex, other factors such as symptom severity, diagnosis (Edwards et al., 2007), culture (Guo et al., 2015; Lane & Addis, 2005), and sexual orientation (Vogel et al., 2011) all intersect with help-seeking behaviors. Consequently, certain BCTs may be more or less effective for different subgroups of men.

Finally, from over 6,000 articles identified from the initial search strategy, only 9 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. This highlights the dearth in literature surrounding studies that seek to evaluate changes in mental health help-seeking in males. Furthermore, only three studies utilized a measure of practical help-seeking (MacNeil et al, 2018; McFall et al., 2000; Syzdek et al., 2016), which also highlights the lack of research using practical help-seeking as an outcome measure.

Conclusion

Historically, men are more hesitant about seeking help for mental health difficulties compared to their female counterparts. Often, this is associated with the disproportionately higher suicide rates in men compared to women (Chang, Yip, & Chen, 2019; World Health Organization, 2017). Nevertheless, a paucity of male-specific interventions designed to improve psychological help-seeking remains.

The current review includes all the available interventions. Furthermore, the specific features within these diverse interventions have been summarized, aiming to provide some clarity within this diverse field. This review has demonstrated the feasibility and usefulness of synthesizing complex behavior change interventions with this method.

Interventions designed to improve psychological help-seeking in men share similarities. Interventions that appear to improve male help-seeking incorporate role models, psychoeducational materials, symptom recognition and management skills, active problem-solving tasks, motivating behavior change, signposting materials, and content that builds on positive masculine traits (e.g., responsibility and strength).

In sum, this review helps provide clarity when trying to understand help-seeking interventions for men. Furthermore, promising strategies to consider when developing future interventions have been discussed, informing both research and clinical practice.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, AJMH_19.03.19_Supplementary_Materials_Amended_clean for Improving Mental Health Service Utilization Among Men: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Behavior Change Techniques Within Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking by Ilyas Sagar-Ouriaghli, Emma Godfrey, Livia Bridge, Laura Meade and June S.L. Brown in American Journal of Men’s Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Ilyas Sagar-Ouriaghli  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3014-3104

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3014-3104

References

- Addis M. E. (2008). Gender and depression in men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(3), 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Addis M. E., Mahalik J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity and the contexts of help-seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. A., Eastman-Mueller P. H., Henderson S., Even S. (2015). Man Up Monday: An integrated public health approach to increase sexually transmitted infection awareness and testing among male students at a Midwest University. Journal of American College Health, 64(2), 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J., Gamma A., Gastpar M., Lépine J. P., Mendlewicz J., Tylee A. (2002). Gender differences in depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252(5), 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer M., Brown J. S., Idusohan H., Coventry S., Manoharan A., Espie C. A. (2009). The development and evaluation of a large-scale self-referral CBT-I intervention for men who have insomnia: An exploratory study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(3), 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C. R., Hagen N. A., Biondo P. D., Cummings G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). National survey of mental health and wellbeing: Summary of results. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. (2018). Men’s health: Time for a new approach. Physical Therapy Reviews, 23(2), 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G., Ricardo C., Nascimento M., Olukoya A., Santos C. (2010). Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Global Public Health, 5(5), 539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugher A. R., Gazmararian J. A. (2015). Masculine gender role stress and violence: A literature review and future directions. Aggression and Violence Behavior, 24, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Begun A. L., Early T. J., Hodge A. (2016). Mental health and substance abuse service engagement by men and women during community reentry following incarceration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(2), 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazina C., Marks L. I. (2001). College men’s affective reactions to individual therapy, psychoeducational workshops, and men’s support group brochures: The influence of gender-role conflict and power dynamics upon help-seeking attitudes. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(3), 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Bonabi H., Müller M., Ajdacic-Gross V., Eisele J., Rodgers S., Seifritz E., Rössler W. (2016). Mental health literacy, attitudes to help-seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(4), 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane J., Richardson M., Johnston M., Ladha R., Michie S. (2015). From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: Comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 130–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q., Yip P. S., Chen Y. (2019). Gender inequality and suicide gender rations in the world. Journal of Affective Disorders, 243, 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. V., Rabinowitz F. E. (2003). Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(2), 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Rafacz J., Rüsch N. (2011). Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 339–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S. M., Wright A., Harris M. G., Jorm A. F., McGorry P. D. (2006). Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(9), 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Dieppe P., Macintyre S., Michie S., Nazareth I., Petticrew M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Association, 337, a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (n.d.). Making sense of evidence. Retrieved November 13, 2017, from http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

- Deeks J. J., Dinnes J., D’amico R., Sowden A. J., Sakarovitch C., Song F., … Altman D. G. (2003). Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment, 7(27), iii–x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais D. C., Lyles C., Crepaz N., & Trend Group. (2004). Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 361–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty T. D., Kartalova-O’Doherty Y. (2010). Gender and self-reported mental health problems: Predictors of help-seeking from a general practitioner. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(1), 213–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne T., Bishop L., Avery S., Darcy S. (2017). A review of effective youth engagement strategies of mental health and substance use interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 487–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S., Tinning L., Brown J. S., Boardman J., Weinman J. (2007). Reluctance to seek help and the perception of anxiety and depression in the United Kingdom: A pilot vignette study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(3), 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englar-Carlson M., Kiselica M. S. (2013). Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(4), 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A. (2016). Using celebrities in abnormal psychology as teaching tools to decrease stigma and increase help-seeking. Teaching of Psychology, 43(4), 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P. J., Lee J. G., Dworkin S. L. (2014). “Real Men Don’t”: Constructions of masculinity and inadvertent harm in public health interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty A. S., Proudfoot J., Whittle E. L., Player M. J., Christensen H., Hadzi-Pavlovic D., Wilhelm K. (2015). Men’s use of positive strategies for preventing and managing depression: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 188, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. M., Alegría M., Prihoda T. J., Copeland L. A., Zeber J. E. (2011). How the relationship of attitudes toward mental health treatment and service use differs by age, gender, ethnicity/race and education. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(1), 45–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. M., Tinsley H. A., Kreuder K. R. (2002). Effects of psychoeducational interventions on opinions of mental illness, attitudes toward help-seeking, and expectations about psychotherapy in college students. Journal of College Student Development, 43(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A., Griffiths K. M., Christensen H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Nguyen H., Weiss B., Ngo V. K., Lau A. S. (2015). Linkages between mental health needs and help-seeking behavior among adolescents: Moderating role of ethnicity and cultural values. Journal of Counseling, 62(4), 682–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer J. H., Vogel D. L. (2010). Men’s help-seeking for depression: The efficacy of a male-sensitive brochure about counseling. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(2), 296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer J. H., Vogel D. L., Heimerdinger-Edwards S. R. (2013). Men’s help-seeking: Examination of differences across community size, education, and income. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(1), 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle S. J., Fortier M., Blake N., Hagger M. S. (2017). Identifying content-based and relational techniques to change behaviour in motivational interviewing. Health Psychology Review, 11(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. G., Diminic S., Reavley N., Baxter A., Pirkis J., Whiteford H. A. (2015). Males’ mental health disadvantage: An estimation of gender-specific changes in service utilisation for mental and substance use disorders in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(9), 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn J. (2015). Men’s health and well-being: The case against a separate field. International Journal of Men’s Health, 14(3), 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Green S. (2005). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman T. C., Glasziou P. P., Boutron I., Milne R., Perera R., Moher D., … Michie S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. British Medical Association, 348, g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom M. A., Stanley I. H., Jonier T. E., Jr. (2015). Evaluating factors an interventions that influence help-seeking and mental health service utilization among suicidal individuals: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt K., Wyke S., Gray C. M., Anderson A. S., Brady A., Bunn C., … Treweek S. (2014). A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9924), 1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson N., Waters E. (2005). Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promotion International, 20(4), 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L., Oliffe J. L., Kelly M. T., Galdas P., Ogrodniczuk J. S. (2012). Men’s discourses of help-seeking in the context of depression. Sociology of Health and Illness, 34(3), 345–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y., Motohashi Y. (2007). Male gender and low education with poor mental health literacy: A population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology, 17(4), 114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr L. K., Kerr L. D., Jr. (2001). Screening tools for depression in primary care: The effects of culture, gender and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. Western Journal of Medicine, 175(5), 349–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Acierno R., Saunders B., Resnick H. S., Best C. L., Schnurr P. P. (2000). Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K. E., Schlichthorst M., Spittal M. J., Phelps A., Pirkis J. (2018). Can a documentary increase help-seeking intentions in men? A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 72(1), 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica M. S., Englar-Carlson M. (2010). Identifying, affirming, and building upon male strengths: The positive psychology/positive masculinity model of psychotherapy with boys and men. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(3), 276–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J. M., Addis M. E. (2005). Male gender role conflict and patters of help-seeking in Costa Rica and the United States. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(3), 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Levant K., Kamaradova D., Prasko J. (2014). Perspectives on perceived stigma and self-stigma in adult male patients with depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 1399–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller-Leimkühler A. M. (2002). Barriers to help-seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacInnes D. L., Lewis M. (2008). The evaluation of a short group programme to reduce self-stigma in people with serious and enduring mental health problems. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(1), 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C. S., Gekoski W. L., Knox V. J. (2006). Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging and Mental Health, 10(6), 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil B. A., Hudson C. C., Leung P. (2018). It’s raining men: Descriptive results for engaging men with eating disorders in a specialized male assessment and treatment track (MATT). Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 23(6), 817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Good G. E., Tager D., Levant R. F., Mackowiak C. (2012). Developing a taxonomy of helpful and harmful practices for clinical work with boys and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(4), 591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall M., Malte C., Fontana A., Rosenheck R. A. (2000). Effects of an outreach intervention on use of mental health services by veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services, 51(3), 369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus S., Bebbington P., Jenkins R., Brugha T. (Eds.) (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital. [Google Scholar]