Abstract

Eating disorders are complex and multifactorial illnesses that affect a broad spectrum of individuals across the life span. Contrary to historic societal beliefs, this disorder is not gender-specific. Lifetime prevalence of eating disorders in males is on the rise and demanding the attention of primary care providers, as well as the general population, in order to negate the potentially life-threatening complications. Current literature has continued to reinforce the notion that eating disorders predominately affect females by excluding males from research, thereby adding to the void in men-centered knowledge and targeted clinical care. To determine what is currently known about eating disorders among males, a scoping review was undertaken, which identified 15 empirical studies that focused on this topic. Using the Garrard matrix to extract and synthesize the findings across these studies, this scoping review provides an overview of the contributing and constituting factors of eating disorders in males by exploring the associated stigmas, risk factors, experiences of men diagnosed with an eating disorder, and differing clinical presentations. The synthesized evidence is utilized to discuss clinical recommendations for primary care providers, inclusive of male-specific treatment plans, as a means to improving care for this poorly understood and emerging men’s health issue.

Keywords: Eating disorders, mental health, male role, gender issues and sexual orientation

Eating disorders (EDs) have historically been addressed as illnesses that only affect young adolescent females; however, the prevalence of EDs in males is on the rise and demanding attention from primary care providers (PCPs) to combat these complex biopsychological disorders (Arnow et al., 2017; MacCaughelty, Wagner, & Rufino, 2016; Pettersen, Wallin, & Bjork, 2016; Thapliyal, Mitchison, & Hay, 2017). EDs in males have been documented in literature as early as the 1690s (Murray et al., 2017); yet men continue to be under-represented in research on the topic (Robinson, Mountford, & Sperlinger, 2012; Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). Recognized as a formal psychiatric condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM–IV), the diagnostic categories of EDs have been revised to include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, and other specified feeding or eating disorder as subcategories (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-10], 2016). For decades, the DSM perpetuated the invisibility of males by including amenorrhea as a diagnostic criterion for AN (Murray et al., 2017). It was not until 2013 that male inclusion was endorsed through the removal of that criterion (APA, 2013).

Based on population survey data, it is estimated that approximately 10 million boys and men in the USA will experience an ED some time in their life (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; National Eating Disorders Association, n.d.). Statistics report that as many as 990,000 Canadians are affected by EDs; males account for close to 200,000, almost 20%, of these cases (House of Commons Canada, 2014). In the UK, the proportion of males who experience EDs is similar to Canadian data (20%–25%; Sweeting et al., 2015). It is estimated that one in four people affected with an ED is male (Dakanalis et al., 2014).

A national representative population sample of more than 36,000 American adults reported the DSM-defined lifetime prevalence of EDs in males (AN, BN, BED) at 1.2% (Udo & Grilo, 2018). The proportion of males reporting lifetime prevalence of BED was far greater than for AN or BN; the female versus male ratio of BED prevalence was 3:1 (Udo & Grilo, 2018). Indeed, some researchers report that males account for 40% of all BED cases (Stanford & Lemberg, 2012; Westerberg & Waitz, 2013). Statistics from the National Eating Disorder Information Centre (National Eating Disorder Information Centre, 2014) report lifetime BED prevalence in males of 2.0% (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007), only 1.5% lower than that of females, a ratio approaching 2:1. There is agreement that these numbers under-report male prevalence due to males being far less likely to disclose their disorder or access treatment (Murray et al., 2017; Weltzin et al., 2012).

With regard to BN manifestations in males, purging is often manifested as compulsive exercise (Strother, Lemberg, Stanford, & Turberville, 2012) and less likely through self-induced vomiting or the use of laxatives (Murray et al., 2017). AN is the most life-threatening ED, but is least frequently seen in male populations; researchers suggest this is because most men are not interested in the emaciated, thin look (Murray et al., 2017). However, a male’s desire for leanness or a “ripped” appearance can drive AN symptomology (Murray et al., 2012).

A principal issue of male EDs is the stigma surrounding the illness. The stereotype that EDs are illnesses that only affect females has led to feelings of shame and isolation among those men affected and, subsequently, delay men’s help-seeking and treatment (Arnow et al., 2017; Bjork, Wallin, & Pettersen, 2012; Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013; Griffiths et al., 2015; Pettersen et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2012). This social stigma can challenge a man’s masculine identity and create internal conflict related to lack of coherence with gender norms (Griffiths et al., 2015). For example, a male participant in a qualitative study described the negative impact of ED stigma: “so it can be quite an isolating thought as well and no other guys have had this problem. What’s wrong with me?” (Robinson et al., 2012, p. 180).

Individuals with EDs, in general, have challenges disclosing their illness to others, and the lack of visibility of men with EDs only exacerbates this reluctance to seek help (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). This creates a dangerous snowball effect: first, men do not receive care and, second, they continue to be under-represented in the media and literature on EDs. The aforementioned deferment of treatment can lead to progressively worsening ED symptomology and an increased risk of dangerous sequelae including death (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). This topic is of dire importance as EDs, namely AN, have the highest mortality and suicide rates of any psychiatric disorder (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013; MacCaughelty et al., 2016). Statistics indicate that 10.5% of individuals diagnosed with AN may die due to their illness (Birmingham, Su, Hlynsky, Goldner, & Gao, 2005).

The history of EDs as a female ailment and the limited research in male EDs informs the need to synthesize the current knowledge base as a means to direct future research and practice to assess and address men’s needs. It is also important to note that the lack of attention to men’s EDs has likely limited PCPs influence and efficiencies in diagnosing and treating male clients. To address these issues, the current scoping review was guided by the following research questions: What is known about male EDs and their treatment? How can primary care providers (PCPs) best recognize and respond to EDs in male clients?

Methods

A scoping review methodology was used to collect evidence on EDs in males to provide a foundational overview of the current evidence (Polit & Beck, 2017). The approach was chosen because it is particularly useful for visualizing the range of available material in an emergent field, summarizing existing literature, and identifying research gaps in order to disseminate synthesized findings to practitioners and policy makers (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The process for this scoping review was guided by the five-stage framework defined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) comprising; (a) identifying the research question, (b) locating relevant studies, (c) selecting suitable studies, (d) charting the data, and (e) summarizing the results.

CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO electronic databases were searched for articles published between 2008 and 2018 inclusive. The following keywords were used for inclusivity: male, men, boys, eating disorder, disordered eating, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, muscle dysmorphia, body dissatisfaction, and gender. Subject headings within PubMed and CINAHL were mapped to distinguish alternative search terms. The Boolean operators “and” as well as “or” were utilized to amalgamate key terms in a variety of combinations, such as “eating disorders AND male,” to narrow search findings. This technique was useful to optimize the applicability of retrieved articles and reduce the final article counts of searched literature.

Selecting Studies

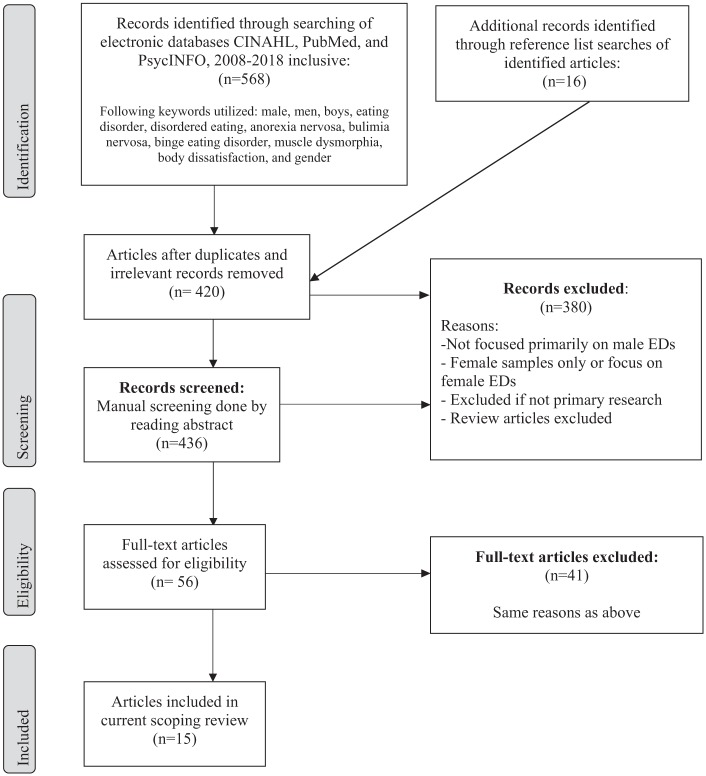

The criteria for inclusion in the scope included the following: (a) a primary focus on EDs in males, (b) empirically-based research, and (c) publication in the English language. Originally, the databases collectively yielded 568 articles through the use of the aforementioned keywords and inclusion criteria. Initial selection was done via manual screening of article abstracts. Studies were excluded if the primary study focus was on female EDs. The focus was kept on primary research, and therefore review articles were also excluded. Additional articles were then located via reference list searches of articles included in the current scoping review. A final count of 15 research articles met the inclusion criteria for the current review (please see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article inclusion/exclusion process.

Charting and Data Analyses

The Garrard matrix method was used to synthesize and structure information from the set of sources (Garrard, 2013; please see Table 1). The matrix focused on study aim(s), study design, study origin, sample population, methods, and key findings. In reading the 15 articles in full numerous times, findings that prevailed across the studies were identified. Working with these preliminary insights, each of the studies was deconstructed and organized into categories to enable constant comparison approaches. For instance, within the gathered data, relevance to PCP practice was specifically queried in order to improve recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. In highlighting overarching patterns, and accounting for diversity across the reviewed articles, two of the authors (SS and JO) compared the articles and discussed their interpretations and the empirical fit in the development of the three themes. All the authors reviewed the content of the themes, driving consensus through several revisions of the material and the writing up of the current article. Three themes were confirmed: (a) risk factors for male EDs, (b) male experiences with their ED, and (c) the presentation of ED in males and clinical considerations. Within the first theme, the following risk factors subthemes were extracted: body dissatisfaction, muscle dysmorphia, sociocultural influences, and other psychiatric/physiological predispositions. Findings for theme 2, male experiences with their ED were organized into these subthemes: experience prior to diagnosis, during treatment, and the recovery process.

Table 1.

Matrix Table of Selected Articles for Scoping Review.

| Author(s)/ year | Aim(s) of study | Study design/sample/origin | Method(s) | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Arnow et al. (2017) | To determine how adolescent males with EDs describe their symptoms prior to learning the “norm” terminology, as well as gaining phenomenological insight on male perspectives of Eds | Phenomenological qualitative study of 10 adolescent males and 10 adolescent females (for comparison) with diagnosed EDs Origin: United States |

One time 45–60 min interviews with open ended questions + nine self-report scales | There were many similarities between sexes re: ED symptomology. Differences included: males stating sports involvement as precipitating disorder and being more cognizant of negative consequences |

| 2. Bjork et al. (2012) | To illustrate how males with prior EDs experience life after recovery | Phenomenological qualitative study of 15 male participants for had completed ED treatment with subsequent recovery Origin: Norway and Sweden |

One time 1 h interviews, face-to-face | Most felt satisfied with life after recovery (accepted body appearance and self-worth), but discussed their feelings of shame with having an ED as a male |

| 3. Burnette, Simpson, and Mazzeo (2017) | To determine the relationship between weight suppression (WS) and eating behaviors/ pathology, and if there are gender differences | Nonexperimental descriptive quantitative design including 827 undergraduate students (234 males) Origin: United States |

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire which assesses disordered eating behaviors and attitudes in the past 28 days | Gender did not play a significant role in WS and dietary restriction, but WS and loss of control was significant only in men. Men higher in WS were more likely to engage in purging behaviors. |

| 4. Dakanalis et al. (2014) | Explored whether difficulties in interpersonal domains and body surveillance affected the body dissatisfaction and ED symptomology in males | Nonexperimental quantitative design including 359 men aged 18–30 from three universities in Italy Origin: Italy |

Multiple online surveys tailored to the following domains: body dissatisfaction, attachment anxiety, body surveillance, social anxiety, and ED symptomatology. All using Likert or similar scales, no qualitative option | Body dissatisfaction, social anxiety, and body surveillance were all significantly related to ED symptomatology. Attachment anxiety moderates the risk for body dissatisfaction and ED symptoms |

| 5. Dearden and Mulgrew (2013) | To explore experiences, intel, and recommend-dations from organizations and service providers of ED in men, as well as examine male experiences with these services | Mixed methods approach (qualitative and quantitative data from surveys); 15 organizations, 10 practitioners with male ED experience, and five men with eating issues Origin: Australia |

Surveys (tailored differently for organizations, practitioners, and men) with open-ended questions at the end | Men found that having a formal diagnosis helped them to continue seeking help. Physical illness was a motivating factor to seek help. Stigma was found to be a treatment barrier. Early recognition and creating “male-friendly” treatment is vital for a males ED recovery |

| 6. Dryer, Farr, Hiramatsu, and Quinton (2016) | To examine the relationship between sociocultural influences and symptomology of EDs and muscle dysmorphia. Also, to gain an understanding of if these relationships are influenced by socially-induced or self-mediated perfectionism | Nonexperimental quantitative design including 158 males aged 18–36 years old (no pre-screening for known EDs) Origin: Australia |

One questionnaire including subsections: Muscle Dysmorphia Questionnaire, Eating Disorder Index questions, Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, and Sociocultural Factors Questionnaire | Influence from the media, teasing, and per influence significantly predicted symptoms of muscle dysmorphia and body dissatisfaction. Symptoms of EDs and muscle dysmorphia may partially depend on pre-existing perfectionist attitudes |

| 7. Fernandez-Aranda et al. (2009) | To study whether outpatient treatment of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is as effective for males as it is with females in improving bulimic symptomology | Mixed methods time series design—19 males with bulimic disorder compared with 150 females with the same diagnosis from an inpatient unit (between 2002 and 2003) Origin: Spain |

Information gathered at different time points of treatment (before, during, 6-month follow-up, 12-month follow-up). Information sources: questionnaires, semistructured interviews, patient’s food diaries | Group CBT treatments were found to be effective in decreasing ED symptoms in both males and females |

| 8. Griffiths et al. (2015) | To explore whether males’ self-stigmatization of seeking psychological help for ED increased chances of having undiagnosed ED | Cross-sectional, nonexperimental quantitative study design- 360 people with diagnosed EDs and 125 with undiagnosed EDs (sample consisted of only 36 males) Origin: Internet survey accessed by participants from United States, Australia, United Kingdom, and other (23 countries total) |

One time internet survey that assessed ED psychopathology, and self-stigma perceptions | Reports of increased self-stigma and being male were associated with increased likelihood of ED being undiagnosed |

| 9. MacCaughelty et al. (2016) | To determine if sex, BMI, ED diagnosis, and age are associated with referral rates for ED consults in an inpatient psychiatric facility | Nonexperimental quantitative design (study part of a larger study). This study included 136 participants, including 39 males with EDs Origin: United States |

Researchers utilized the Structured Clinical Interview for DMS-IV Diagnosis to assess for EDs. Based on these findings, comparisons were made if the patients received referrals after physician assessment | Being male and overweight was a significantly significant result for not receiving a consult/referral for ED services in hospital |

| 10. Mayo and George (2014) | To study the relationship between body dissatisfaction, perceptual attractiveness, and EDs in male university students | Correlational study, nonexperimental design including convenience sample of 339 male and 441 female university students Origin: United States |

Risk for EDs was assessed via: Eating Attitudes Test (EAT); body dissatisfaction and perceived attractiveness was assessed via: Bodybuilder Image Grid | 28% of males scored at risk for disordered eating. Higher scores on the EAT correlated with fat dissatisfaction. Majority of males indicated wanting leaner and muscular body types |

| 11. Pettersen et al. (2016) | To explore male experiences in their ED recovery process (and what was helpful from clinicians) | Phenomenological Qualitative study design—15 males aged 19–52 who had previously completed treatment for an ED and experienced recovery Origin: Norway and Sweden |

In-depth interviews lasting 1–2 h with structured line of questioning | Emerged themes in recovery process: need for change, commitment to leave ED in the past, interpersonal changes, and searching for life beyond ED |

| 12. Raisanen and Hunt (2014) | To examine young male perceptions of ED symptoms, how they recognized to seek help, and understand their initial experiences with primary care. | Qualitative design—39 participants, including 10 men aged 16–25 with a known ED (bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa) Origin: United Kingdom |

In person interviews which began with an invitation to the participant to speak freely on his experiences of having an ED. This was followed by semistructured questions. | Many men were initially unable to attribute their behaviors to an ED due to gendered underpinnings of the illness. This led to dismissal of symptoms and presentation late in illness trajectory. Also lack of knowledge from primary care providers and missed diagnoses. |

| 13. Robinson et al. (2012) | To investigate experiences of males living with an ED, including what it is like to seek and receive treatment for the ED | Interpretive Phenomenological Qualitative study design—six men with EDs receiving treatment (ages 24–56) Origin: London, United Kingdom |

Semistructured interview which lasted 60–90 min | The biggest challenge many men face is admitting to having an ED. Other themes included: fear of a negative reaction from other people, and the significance of feeling understood by professionals. |

| 14. Stanford and Lemberg (2012) | To test a developed ED assessment tool tailored specifically for men and, in doing so, promoting a clearer understanding of male EDs to enhance diagnosis and treatment | Nonexperimental study design. A sample population of 108 participants from an ED and substance use treatment center (78 males). Of this sample, 66 had a confirmed ED Origin: United States |

Participants were given the newly developed “Eating Disorder Assessment for Men” questionnaire; 50 items with Likert scale | Predicted an ED correctly in 82.1% of the men. A four-structure model was determined the best to use, including: binge eating, body dissatisfaction, muscle dysmorphia, and disordered eating. |

| 15. Weltzin et al. (2012) | To examine the outcomes of males with EDs receiving treatment in a residential treatment facility, as well as discuss co-morbid issues for males with EDs. | Pretest posttest cohort study including 111 males with EDs receiving treatment in a residential treatment facility (over the years 2005 and 2012) Origin: United States |

Results based on measures taken within one week of admission and on discharge: ED Examination Questionnaire, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, EDs Inventory-3, Compulsive Activity Checklist, Beck Depression Inventory-11. | There were positive treatment outcomes in males at discharge, indicated by weight restoration, improved eating behaviors and psychological well-being. |

Findings

Among the set of 15 articles, five (33.3%) of the studies were qualitative designs, eight quantitative (53.3%), and two (13.3%) employed a mixed methods approach. None of the studies were clinical trials or experimental designs. Four of the qualitative studies employed phenomenological approaches. Seven quantitative and the two mixed methods studies relied on survey and questionnaire measures. One quantitative study (MacCaughelty et al., 2016) utilized the DSM-IV Structured Clinical Interview. Six of the 15 studies were conducted in the USA; eight studies originated in the UK, Australia, or Western Europe, and one Internet-based study enrolled participants from 23 countries.

Risk Factors for Male EDs

Body dissatisfaction

Discrepancies between men’s present body image and their ideal body image is defined as body dissatisfaction (BD; Mayo & George, 2014). Four studies indicated that there is a positive correlation between BD and development of an ED, especially in males who aspire to achieve a mesomorphic body type (Dakanalis et al., 2014; Dryer et al., 2016; Mayo & George, 2014). Dakanalis et al. (2014) suggested that approximately 50% of the general male population was dissatisfied with their body, making BD one of the most robust risk factors for disordered eating and ED development. A study by Burnette et al. (2017) reported that men, in particular, with higher BD and weight suppression, were more likely to engage in loss of control eating and subsequent purging behaviors.

Muscle dysmorphia

Five studies discussed muscle dysmorphia (MD) as a risk factor for EDs specific to male populations (Arnow et al., 2017; Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013; Dryer et al., 2016; Mayo & George, 2014; Weltzin et al., 2012). MD was recognized in the DSM-IV as a subcategory of body dysmorphic disorder, and was defined as the preoccupation that one’s body is not lean or muscular enough (Dryer et al., 2016; Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). This preoccupation is particularly prevalent in males, who often desire high levels of musculature coupled with low body fat (Dryer et al., 2016). The male pursuit of this body type that is often unachievable encourages a culture of strict disordered eating, which can develop into an ED (Dryer et al., 2016). Mayo and George (2014) investigated the relationship of perceptual attractiveness and risk of EDs in male university students. More than half (n = 172.9, 51%) of the males surveyed desired an ideal body figure that could only be obtained through the use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (Mayo & George, 2014). EDs perpetuated by this desire were manifested by extreme measures to change one’s body (e.g., excessive exercise or obsession with monitored caloric intake; Dryer et al., 2016; Raisanen & Hunt, 2014).

Sociocultural influences

Sociocultural influences can negatively influence MD, BD, and subsequently EDs, by portraying a socially prescribed level of body perfectionism (Dryer et al., 2016; Weltzin et al., 2012). The media and popular culture (e.g., television, movies, magazines, computer games, action figures) constantly showcase lean and muscular body image ideals that may evoke feelings of shame in men who fail to embody those aesthetics (Dryer et al., 2016; Mayo & George, 2014). This encouragement of BD and MD challenges men across their life span. First, adolescent boys may experience pressures to achieve the “perfect” body. These pressures are exacerbated as men age, and struggle to maintain this body image while balancing new work responsibilities and life commitments (Dryer et al., 2016).

Other social factors known to predispose men to disordered eating and/or EDs include the desire to avoid being teased for weight by peers (Dryer et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2012) and participation in high-level sports (Arnow et al., 2017; Weltzin et al., 2012). Men are commonly pressured to lose or gain weight to drive optimal athletic performance (Arnow et al., 2017; Weltzin et al., 2012). Therefore, men may begin their disordered eating behaviors in an attempt in promote health through weight loss, but become immersed in a vicious cycle of restrictive intake and excessive exercise—thus, their involvement in sports can catalyze their ED (Arnow et al., 2017).

Other psychiatric/psychological predispositions

EDs are classified psychiatric disorders and the risk factors include precipitating psychiatric conditions. Conditions that can increase male risk for developing EDs are depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and specific mood disorders (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013). Anxiety and OCD exacerbate compulsive behaviors, social phobia, and the fear already involved with having an ED (Dakanalis et al., 2014). Compounded depression is a major inhibitor to recovery as it can hinder men’s receptiveness to treatment (Weltzin et al., 2012). Personality traits such as low self-esteem and perfectionism have been reported to increase male risk (Dryer et al., 2016; Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). Furthermore, men with EDs are two times more likely to have a co-morbid substance-use disorder (Weltzin et al., 2012). These substances can include illicit drugs including cocaine, or prescription stimulants to suppress appetite (Weltzin et al., 2012). Additionally, stress, trauma, and substance use in the family can precipitate the progression of an ED (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014).

Male Experiences With Their ED

The strong representation of qualitative research, mixed methods, and clinical interviews in this data set provided in-depth accounts from men affected by EDs. Their experiences were discussed in terms of diagnostic trajectory: prior to diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

Experiences prior to diagnosis

Males are often unaware that their behaviors are characteristic of an ED (MacCaughelty et al., 2016). This phenomenon was illustrated by a participant in a qualitative study on delayed help-seeking in males with EDs: “I didn’t know the symptoms, didn’t know anything, it was just, to me it was just happening. I didn’t really know what was going on” (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014, p. 3). Similarly, a male participant in a mixed methods study disclosed his lack of awareness of EDs in men: “I have not sought treatment because there is not enough awareness about eating disorders. . . so I never thought I was sick enough [to need] treatment” (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013, p. 599). The invisibility of EDs in males resulted in some men believing that there was no help; they presumed that their idiosyncratic symptoms were not treatable and simply attributable to other aspects of their life (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). This ultimately led to patterns of behavior characterized by widespread reluctance to seek help or treatment.

When men realize they have a significant health problem, they may also become burdened with an intrapersonal struggle for self-acceptance (Bjork et al., 2012; MacCaughelty et al., 2016; Pettersen et al., 2016). Traditionally, male gender roles include conformity with being independent, self-reliant, and resilient (Griffiths et al., 2015). As a result, the self-judgment and stigma surrounding the notion of needing help correlated with an increased likelihood for men to postpone seeking psychological or medical care (Griffiths et al., 2015). Feeling emasculated, men tended to conceal their ED from others (Bjork et al., 2012), and therefore became isolated from their social networks (Pettersen et al., 2016). Some men report hiding their disorders for many years (Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). It is for these reasons that males frequently presented at a later age (Weltzin et al., 2012) and/or later stage of their illness trajectory (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014), which for males with AN was extremely dangerous.

Treatment experiences

While receiving treatment for their ED, men have reported a desire for gender-sensitized information that rectifies societal constructs of EDs as only affecting women (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). Female-biased health information that communicated the side effects of low body mass indexes (BMIs) from EDs, including amenorrhea and female infertility, left men confused and frustrated (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). A participant in a mixed methods study examining male experiences with ED services stated “needing a low BMI to be diagnosed with [AN] is like needing to be terminally ill to be diagnosed with cancer” (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013, p. 598). This man wanted the psychological aspects of his illness to be taken more seriously, despite having a normal BMI. Men in care cited challenges around receiving the wrong or no diagnosis, stating that receiving a formal ED diagnosis helped motivate them to continue seeking treatment (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013). During the treatment journey, males appreciated when their PCPs were attentive and committed to their recovery (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). This involved affirming multiple expressions of masculine behavior, challenging gender stereotypes, and empowering the patient (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013).

Recovery process

Three articles explored men’s experiences of recovering from EDs. Bjork et al. (2012) reported that while each man experienced his own struggles and triumphs, a recurrent expression from male participants was an overwhelming sense of freedom. Common themes men described in ED recovery were: (a) acceptance of body appearance, (b) regaining self-worth, and (c) accepting losses (Bjork et al., 2012; Pettersen et al., 2016). To accept their body, many males described having to replace their compulsive exercise obsession with a relaxed attitude on appearance and working out for recreation (Bjork et al., 2012). In recovery, there was also a newfound healthy relationship with food, no longer allowing it to dominate their thoughts (Bjork et al., 2012). Accepting losses and managing grief were key processes in recovery as many men had been preoccupied with their ED for several years (Pettersen et al., 2016). During these years, the ED manifested profound losses such as missed work, dropping out of school, and/or lack of romance and intimacy (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013; Pettersen et al., 2016). Working through the recovery process, while extremely difficult, eventually entailed men constructing a new self-identity, free of their former self-imposed restrictions.

The Presentation of ED in Males and Clinical Considerations

The lack of awareness of EDs in males can hinder the ability of both patients and PCPs to classify the behaviors as problematic (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). Males may develop personal routines of purging and bingeing, but interpret them as coping mechanisms rather than a discrete disorder (Burnette et al., 2017; Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). They may not perceive their actions as disordered or may assign them to a different disorder. For example, changes in eating patterns, weight loss, self-harm, and increased isolation may be attributed to depression or another psychiatric disorder (MacCaughelty et al., 2016). Men have reported body composition changes as a “solution” to problems, such as bullying or obesity, thereby decreasing their willingness to outwardly disclose the details of their disorders (Robinson et al., 2012).

Men are inclined to see their PCP with physical illness rather than psychological complaints (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013), and they are particularly unlikely to seek help for psychological conditions including EDs (Griffiths et al., 2015). Male-specific research indicates men are known to hide or ignore their disorders for years due to the absence of safe viable options (Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). Men have also reported not being taken seriously or being misdiagnosed by their PCP, despite countless visits presenting ED symptoms (Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013). A participant in Raisanen and Hunt’s (2014) qualitative study reported being told by a clinician to “not be weak but strong and deal with the problem” (p. 5). This same participant detailed being admitted to the hospital following a suicide attempt. Although men may not present in clinics as frequently as women, the seriousness to mental and physical well-being warrants careful attention from PCPs. The research does suggest that, compared to women, men’s ED symptoms are more likely to be overlooked by professionals. For example, a study examining gender influences on ED consult rates reported that 25.6% (n = 10) of men in their sample with current EDs were not referred to specialized care (MacCaughelty et al., 2016). Confounding this finding was additional evidence that men tended to only speak about their ED symptoms with a health professional (Pettersen et al., 2016) due to the fear of a negative response or judgment from others in their lives (Robinson et al., 2012). These patterns create a major obstacle to recovery and, consequently, the rarity of PCP encounters with this population weakens skilled assessment and diagnostic abilities (MacCaughelty et al., 2016).

The quality of the initial contact with a clinician can dictate a man’s willingness to return for follow-up care (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014), which further reinforces the importance of PCPs’ skills for assessing EDs in males; presentation in males may be difficult to recognize in the disorder’s infancy as EDs are habitually associated with extreme thinness (Arnow et al., 2017; Burnette et al., 2017; Dryer et al., 2016). PCPs need to be aware of males who may present as striving for extreme muscular bodies with low body fat (Arnow et al., 2017; Dryer et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2017). Other symptoms may also be misunderstood; for instance, a significant, and potentially life-altering, complication of untreated EDs is the potential for sexual dysfunction (e.g., inability to achieve an erection; Dearden & Mulgrew, 2013). In order to effectively diagnose and treat these men, PCPs must be cognizant of subtle risk and warning signs which prompt questions to solicit men’s self-disclosures about symptoms that may not be observable in the clinical setting or consult. Overall, it is important for clinicians to be aware that EDs can affect males of multiple shapes, weights, sizes, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds (MacCaughelty et al., 2016).

There are ED scales available to provide objective data to support a PCPs’ diagnosis but, studies report that men tend not to score as high on the available diagnostic tools, even when symptoms are equivalent to their female counterparts, suggesting the need for male-specific screening tools (Arnow et al., 2016). Previously, the risk for ED was rated and assessed based on silhouettes ranging from skinny to obese (Mayo & George, 2014). These measures do not include varying degrees of muscularity, which may more accurately capture a male’s perspective of the body (Mayo & George, 2014). The multiple measures of ED symptomology that include questions on buttocks and hips are more applicable to female body image concerns (Dryer et al., 2016). A male-specific assessment tool known as the Eating Disorder Assessment for Men (EDAM) incorporates factors that measure symptoms more highly correlated to male behaviors including MD, BD, preoccupation with food/binge eating, and disordered eating (Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). The EDAM correctly predicted an ED in 82.1% (n = 64) of men (Stanford & Lemberg, 2012). Tools developed by other authors, such as The Drive for Muscularity Scale (McCreary & Sasse, 2000) and Male Body Checking Questionnaire (Hildebrandt, Walker, Alfano, Delinsky, & Bannon, 2010), have demonstrated good reliability and validity (Arnow et al., 2016). It is recommended that clinicians also assess men for levels of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, emotional regulation, and quality of life (Arnow et al., 2016).

The research in this scope indicated that the majority of males who do seek treatment have positive outcomes; in fact, male success rates are often greater than those of females (Arnow et al., 2017; Bjork et al., 2012). If men don’t seek timely medical care, disease complications can increase to risk mortality. Hospital admission may also occur due to ED-related suicidality (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). Long-term complications have effects beyond the patient, as family and friends are often exposed to the turmoil alongside the male. There are also financial burdens, such as lost wages of patients and caregivers, as well as costs to the health-care system.

Discussion

The current scoping review provides an important synthesis of existing literature investigating the contributing and constituting factors related to EDs in males. Overall, the findings demand PCPs develop awareness about ED in males to advance illness management and enhance long-term prognosis. When men seek treatment, they are typically goal-oriented and self-directed, carrying high expectations of their PCP (Pettersen et al., 2016). PCPs play a key role in detection of EDs as they often act as a first point of contact for men accessing the health-care system. By skillfully recognizing early symptoms, PCPs can promptly diagnose, manage, and refer patients in order to minimize the risk of future complications (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). This is perhaps the most important finding in this scoping review—that a major barrier to men receiving medical care has been PCP inexperience with male EDs. This same issue has been underscored in nonscientific autobiographical accounts by men with EDs (Thapliyal et al., 2017). Whether a male presents to the clinic with outward declarations of disordered eating or vague, nonspecific complaints, PCPs must lobby men to elaborate in order to better understand the underlying issues. Recognition and diagnoses can also be thwarted by the fact that the following ED complications may present as initial complaints in primary care: cardiac arrhythmias, bradycardia, delayed gastric emptying, and endocrine abnormalities (e.g., low testosterone; Murray et al., 2017). PCPs may also encounter male patients presenting with frequent unexplained fractures (e.g., hands, feet, pelvis, clavicle; Murray et al., 2017). Low bone mass density caused by an ED could be easily missed in this case (Murray et al., 2017). When left untreated, BN can lead to dental erosion and severe gastrointestinal problems (Cottrell & Williams, 2016).

While assessing an ED, the PCP should include general questions on eating habits in their intake interview (MacCaughelty et al., 2016). For example, asking about how many meals are eaten in one day, how much time is spent thinking about food or weight per day, and feelings of loss of control while eating (MacCaughelty et al., 2016). These simple questions can help identify disordered eating habits (MacCaughelty et al., 2016) and other existing risk factors. Once an ED is suspected, the first few minutes of the encounter are crucial to gain trust and buy-in from the patient (Palmer, 2014). Due to the sensitivity associated with being a minority in the ED service-user population (Robinson et al., 2012), as well as the vulnerability of the illness in general, PCPs need to ensure a judgment-free environment to establish a therapeutic relationship (Palmer, 2014). While building said relationship, it is important to understand the patients’ fears, struggles, hopes, and expectations prior to developing a treatment plan (Palmer, 2014).

Once buy-in from the patient is gained, a complete physical exam and diagnostic work-up is required (Cottrell & Williams, 2016). There are no male-specific gold standard or best-practice guidelines available yet (Murray et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2012). Lab work should include complete blood count levels, electrolytes, liver function tests, and other metabolic levels (e.g., thyroid stimulating hormone; Cottrell & Williams, 2016). Additional investigations may also be required including an electrocardiogram and urinalysis (Cottrell & Williams, 2016). Based on the results of these diagnostics, medical treatment should be provided as necessary. In cases of severe medical complications or suicidal ideation, immediate referral to the emergency department is warranted. Prompt referral is a vital component of treating male ED (Cottrell & Williams, 2016). A comprehensive interdisciplinary approach ensures holistic care is received. Priority referrals to the following professionals are critical: psychiatrist, therapist, dietician or nutritionist, and ED specialist if available (Cottrell & Williams, 2016). Treatment may include an array of psychological interventions and pharmacological management (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014). Admission to hospital or inpatient treatment centers would be dependent on unique case characteristics. Research on cognitive behavioral therapy indicates it is effective in decreasing ED symptoms in men (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2009). An important part of a PCP’s job is to continuously assess/reassess the management plan, monitor vital signs and BMI on every visit, and attend to the unique needs of each patient (Cottrell & Williams, 2016). Through the improvement of recognition, diagnosis, and treatment, males will be more prevalent in the ED population, thereby enhancing care and increasing general awareness. Overall, PCPs need to work cohesively to destigmatize male EDs and recognize early symptoms in order to improve patient care outcomes and the overall well-being of men and their families (Raisanen & Hunt, 2014).

The current findings demonstrate how sex and gender biases can obscure EDs in men and underline the urgent need to redress how PCPs and the public understand EDs. The sex and gender biases associated with EDs in men bear remarkable similarity to social and clinical issues associated with depression in men. Like EDs, men experiencing depressive symptoms have reported feeling stigmatized by both the disorder and assertions that it is a predominately female illness (Oliffe & Phillips, 2008). Like EDs in men, it has been argued that the screening and assessment tools for depression tend to be biased toward diagnosing women (Oliffe & Phillips, 2008). Mental health research investigating the role of masculinity in men’s helping-seeking for depression concluded that tailoring and targeting interventions may improve uptake and efficacy of treatments (Seidler, Dawes, Rice, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2016). Male group therapy allows participants to experience essential emotional expression by creating a safe space for open discussion of ED symptoms in the presence of others with similar experiences (Weltzin et al., 2012). This may assist with destigmatizing the illness. Men have unique needs and discussion points can be targeted to topics such as: emasculation, identity (Robinson et al., 2012), muscle-building, and exercise (Thapliyal et al., 2017). Research validates that male therapy groups can facilitate acceptance and positive treatment outcomes. Literature on the use of strength-based approaches suggests that an emphasis on affirming emotional strengths, virtues, and capacities enables men to flourish and grow throughout their life (Englar-Carlson & Kiselica, 2013). By using this approach, and focusing on positive potential, PCPs can help empower men, reduce defensiveness, and establish effective therapeutic relationships (Englar-Carlson & Kiselica, 2013). A strength-based approach will aid men in acknowledging their problems and accepting professional help as a conduit to healthy self-management (Englar-Carlson & Kiselica, 2013).

There remain several limitations in the current literature on male EDs. More attention needs to be paid to the male presentations in each specific ED subcategory. By doing so, the number of misdiagnosed males, or males diagnosed with ‘Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder’ (OSFED) could be effectively addressed. More in-depth research on the role of gender norms and pressures for men to conform to rigid masculine ideals may increase our understanding of EDs in men. Although this small body of research elucidated the concerns related to sex and gender biases in EDs, there is a gap in terms of connecting such complex disorders with nuanced gender studies research. Future research should also utilize larger sample populations with diverse ethnicities and age groups, and follow patients over the illness trajectory. This would involve longitudinal studies to better understand trends across the life course and assess generational shifts. While the removal of amenorrhea from the DSM-IV ED diagnostic was a step forward (Thapliyal et al., 2017), more research needs to be done to correlate male-specific concerns, such as MD, to the development of EDs. This would mean focusing attention on the drive for muscularity as distinct from thinness. It is also important to remember that some males may present with the classic drive for thinness (Murray et al., 2017). Investigating the impacts of socioeconomic status, culture, and sexual identity would similarly broaden the current understanding of male EDs. In addition, future research might usefully include attention to male’s coping with criticism and perceived weakness in the context of ED risk (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2009). This literature would aid in creating ED diagnostic tools and practice guidelines with increased sensitivity and specificity to recognizing the psychopathology of at-risk males. It is imperative to address the aforementioned limitations in order to diminish the misconceptions that males are not affected by EDs, and raise awareness on the seriousness of misdiagnosing and undertreating this subpopulation. Highlighting the growing number of men affected will also help reduce isolation and stigmas presently felt by those with this disorder.

Conclusion

Whilst male EDs were once perceived as rare, there is significant evidence revealing them as an emergent men’s health issue. It is no longer tenable, nor safe, to presume that males account for a negligible proportion of ED patients. The current scoping review findings highlight the importance of addressing this issue by being cued to an array of risk factors, varying presentations, potential complications, and unique experiences of men with EDs. The outlined recommendations for PCPs can be incorporated to expedite recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of EDs in the male population. In turn, by sharing experiences of working with men experiencing EDs, and evolving general knowledge on this topic, PCPs can contribute to advancements in effectually treating this challenging men’s health issue. By doing so, the historical gender biases surrounding this disorder will be addressed to advance the health outcomes of males with ED and their families.

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to acknowledge my amazing partner, Baldeep. You have been the most consistent source of encouragement, motivation, and laughter throughout this process. I am eternally grateful for your support. Next, to my biggest cheerleaders, my parents, I thank you for always pushing me to reach for nothing less than the stars. Without you two, and your unconditional love, this would not be possible.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by Movember (Grant number #11R18296). This article is based on partial requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing – Nurse Practitioner completed at University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

ORCID iD: Simrin Sangha  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

References

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow K. D., Feldman T., Fichtel E., Lin I. H., Egan A., Lock J., . . . Darcy A. M. (2017). A qualitative analysis of male eating disorder symptoms. Eating Disorders, 25(4), 297–309. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2017.1308729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham C. L., Su J., Hlynsky J. A., Goldner E. M., Gao M. (2005). The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38(2), 143–146. doi:10.1002/eat.20164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork T., Wallin K., Pettersen G. (2012). Male experiences of life after recovery from an eating disorder. Eating Disorders, 20(5), 460–468. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette C. B., Simpson C. C., Mazzeo S. E. (2017). Exploring gender differences in the link between weight suppression and eating pathology. Eating Behaviors, 27, 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell D. B., Williams J. (2016). Eating disorders in men. The Nurse Practitioner, 41(9), 49–55. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000490392.51227.a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A., Timko C., Favagrossa L., Riva G., Zanetti M., Clerici M. (2014). Why do only a minority of men report severe levels of eating disorder symptomatology, when so many report substantial body dissatisfaction? examination of exacerbating factors. Eating Disorders, 22(4), 292–305. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.898980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearden A., Mulgrew K. E. (2013). Service provision for men with eating issues in Australia: An analysis of organisations’, practitioners’, and men’s experiences. Australian Social Work, 66(4), 590–606. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2013.778306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dryer R., Farr M., Hiramatsu I., Quinton S. (2016). The role of sociocultural influences on symptoms of muscle dysmorphia and eating disorders in men, and the mediating effects of perfectionism. Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 174–182. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2015.1122570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englar-Carlson M., Kiselica M. S. (2013). Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(4), 399–409. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00111.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Aranda F., Krug I., Jiménez-Murcia S., Granero R., Núñez A., Penelo E., . . . Treasure J. (2009). Male eating disorders and therapy: A controlled pilot study with one year follow-up. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(3), 479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J. (2013). Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method (4th ed.). Mississauga, ON: Jones and Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S., Mond J. M., Li Z., Gunatilake S., Murray S. B., Sheffield J., Touyz S. (2015). Self-stigma of seeking treatment and being male predict an increased likelihood of having an undiagnosed eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(6), 775–778. doi: 10.1002/eat.22413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt T., Walker D. C., Alfano L., Delinsky S., Bannon K. (2010). Development and validation of a male specific body checking questionnaire. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(1), 77–87. doi: 10.1002/eat.20669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Canada. (2014). Statistics on eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/41-2/FEWO/report-4/page-36#3

- Hudson J. I., Hiripi E., Pope H. G., Jr, Kessler R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, [ICD-10]. (2016). Eating disorders. Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/F50

- MacCaughelty C., Wagner R., Rufino K. (2016). Does being overweight or male increase a patient’s risk of not being referred for an eating disorder consult. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(10), 963–966. doi: 10.1002/eat.22556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo C., George V. (2014). Eating disorder risk and body dissatisfaction based on muscularity and body fat in male university students. Journal of American College Health, 62(6), 407–415. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.917649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary D. R., Sasse D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48(6), 297–304. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. B., Nagata J. M., Griffiths S., Calzo J. P., Brown T. A., Mitchison D., . . . Mond J. M. (2017). The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. B., Rieger E., Hildebrandt T., Karlov L., Russell J., Boon E., … Touyz S. W. (2012). A comparison of eating, exercise, shape, and weight related symptomatology in males with muscle dysmorphia and anorexia nervosa. Body Image, 9(2), 193–200. doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Eating Disorder Information Centre. (2014). Clinical definitions. Retrieved from http://nedic.ca/node/806

- National Eating Disorders Association. (n.d.). Eating disorders in men and boys. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/general-information/research-on-males

- Oliffe J. L., Phillips M. J. (2008). Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men’s Health, 5(3), 194-202. Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/36428793/Men__depression_and_masculinities_A_review_and_recommendations.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1550714651&Signature=FtBGsZAwaIm7ywOFJP6rThqhujM%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DMen_depression_and_masculinities_A_revie.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Palmer B. (2014). Helping people with eating disorders: A clinical guide to assessment and treatment. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Pettersen G., Wallin K., Björk T. (2016). How do males recover from eating disorders? an interview study. BMJ Open, 6(8), 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Raisanen U., Hunt K. (2014). The role of gendered constructions of eating disorders in delayed help-seeking in men: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open, 4(4), 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K. J., Mountford V. A., Sperlinger D. J. (2012). Being men with eating disorders: Perspectives of male eating disorder service-users. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(2), 176–186. doi: 10.1177/1359105312440298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Dawes A. J., Rice S. M., Oliffe J. L., Dhillon H. M. (2016). The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 106-118. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford S. C., Lemberg R. (2012). Measuring eating disorders in men: Development of the eating disorder assessment for men (EDAM). Eating Disorders, 20(5), 427–436. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strother E., Lemberg R., Stanford S. C., Turberville D. (2012). Eating disorders in men: Underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood. Eating Disorders, 20(5), 346–355, doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting H., Walker L., MacLean A., Patterson C., Räisänen U., Hunt K. (2015). Prevalence of eating disorders in males: A review of rates reported in academic research and UK mass media. International Journal of Men’s Health, 14(2). doi: 10.3149/jmh.1402.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal P., Mitchison D., Hay P. (2017). Insights into the experiences of treatment for an eating disorder in men: A qualitative study of autobiographies. Behavioral Sciences, 7(2), 38. doi: 10.3390/bs7020038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T., Grilo C. M. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biological Psychiatry, 84(5), 345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltzin T. E., Cornella-Carlson T., Fitzpatrick M. E., Kennington B., Bean P., Jefferies C. (2012). Treatment issues and outcomes for males with eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 20(5), 444–459. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg D. P., Waitz M. (2013). Binge-eating disorder. Osteopathic Family Physician, 5(6), 230–233. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877573X13001342 [Google Scholar]