Short abstract

Fetal tachycardia is a rare complication during pregnancy. After exclusion of maternal and fetal conditions that can result in a secondary fetal tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia is the most common cause of a primary sustained fetal tachyarrhythmia. In cases of sustained fetal supraventricular tachycardia, maternal administration of digoxin, flecainide, sotalol, and more rarely amiodarone, is considered. As these medications have the potential to cause significant adverse effects, we sought to examine maternal safety during transplacental treatment of fetal supraventricular tachycardia. In this narrative review we summarize the literature addressing pharmacologic properties, monitoring, and adverse reactions associated with medications most commonly prescribed for transplacental therapy of fetal supraventricular tachycardia. We also describe maternal monitoring practices and adverse events currently reported in the literature. In light of our findings, we provide clinicians with a suggested maternal monitoring protocol aimed at optimizing safety.

Keywords: Fetal arrhythmia, fetal supraventricular tachycardia, pharmacology, medication safety, digoxin, flecainide, sotalol, amiodarone

Introduction

Fetal tachycardia is defined by a fetal heart rate greater than 180 beats per minute.1,2 It is estimated to affect 0.4–0.6% of all pregnancies, and it occurs mostly in the third trimester.1 Fetal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) detected at a routine obstetric visit is to be carefully distinguished from frequent cardiac ectopy, and tachycardia secondary to fetal or maternal conditions (such as fetal hypoxia, maternal fever, hyperthyroidism, or anemia).2–4 It is characterized by a 1:1 atrioventricular conduction, and is the most common cause of sustained fetal tachyarrhythmia, with heart rates commonly reaching more than 220 beats per minute.5 Fetal SVT further requires assessment in centers with access to specialized fetal/pediatric cardiology and high-risk pregnancy care.2,4 A diagnosis of fetal SVT can be made using Doppler ultrasound assessment of left ventricular inflow and outflow tracts and M-mode assessment of atrial and ventricular wall movement on fetal echocardiography.5,6 Although the predominant mechanism for fetal SVT is atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, atrial ectopic tachycardia, and permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia can also occur.7,8 Fetal tachycardia may cause low cardiac output, ascites, pleural and/or pericardial effusions, skin edema, and in some cases can lead to hydrops fetalis, a severe manifestation of fetal congestive heart failure.5,6 Hydrops is identified at presentation or develops in about 40–50% of fetuses with SVT.9 The risk of fetal hydrops increases with sustained SVT, defined as tachycardia occurring majority of time or 50% or more of the time monitored.9 Earlier gestational age at time of diagnosis of SVT is also an independent risk factor for the development of fetal hydrops.10

As per the scientific statement of the American Heart Association, patients with sustained fetal SVT, or patients with non-sustained fetal SVT with evidence of cardiac dysfunction and/or hydrops, can be treated with transplacental therapy, with the proviso that they are not near term.5 Antiarrhythmic agents are thereby given to the pregnant patient who will serve as the vehicle for fetal delivery of therapy.5 In setting of severe therapy-resistant arrhythmia, significant myocardial dysfunction, or progressing hydrops however, direct fetal therapy or delivery by early caesarean section may be considered.2,6 While caesarean section may be the preferred mode of delivery in patients with persistent tachycardia because of the inability to perform adequate fetal monitoring in this setting, a trial of labor at term may be reasonable in patients with either spontaneous or medically induced resolution of fetal SVT.6 Maternal mirror syndrome, a rare complication of fetal hydrops characterized by maternal edema, is frequently associated with preeclampsia and may further affect clinical management.11,12 This could be particularly important in the setting of maternal hypertension requiring pharmacologic therapy whereby drug interactions could occur. Although fetal hydrops and maternal mirror syndrome could potentially resolve with treatment of the underlying fetal SVT, expectant management in this setting should be undertaken with caution.12 In case of maternal deterioration, delivery should not be delayed.12

Given that antiarrhythmic therapy can have profound maternal adverse effects, initial treatment and dose adjustment should be performed, bearing in mind the pharmacokinetics considerations alongside close maternal monitoring for adverse effects. In this narrative review, we discuss treatment modalities and safety considerations during administration of the common antiarrhythmic medications used for this condition, and summarize currently reported maternal monitoring practices and maternal adverse events during antiarrhythmic therapy of fetal SVT. We also provide a suggested monitoring protocol for women in whom therapy is administered for the treatment of fetal SVT.

Approach to therapy for fetal SVT

The initial treatment of fetal SVT includes the cessation of precipitating factors such as tobacco, caffeine, and decongestants.6,13 In the case of sustained fetal SVT transplacental administration of antiarrhythmic agents is considered. Since there is no agreed consensus or international guidelines currently addressing optimal transplacental therapy of fetal SVT, choice of therapy is made on a case-by-case basis.8 Most of the available literature suggests initial treatment with digoxin alone or in combination with a second-line agent, which would typically be flecainide, sotalol, or amiodarone.7,14,15 Some investigators, however, have proposed sotalol or flecainide as first-line agents.16–19 Occasionally, amiodarone has also been prescribed.20,21

Digoxin

Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside and has long been the drug of choice for management of fetal SVT without hydrops fetalis.5 As digoxin is excreted by the kidneys, the half-life in the setting of normal kidney function is about 40 h, and dosing adjustments are required for patients with renal impairment.23 The suggested digoxin loading dose is 1 mg intravenously in divided doses over a 24-h period, with a maintenance dose of 0.25 mg orally twice a day to achieve a therapeutic range of 1–2 µg/L serum digoxin.2,8

Given the narrow therapeutic index of this drug parameters for maternal toxicity should be closely observed. Clinical signs of maternal toxicity include vision changes (such as alteration in color vision, scotoma, or blindness) gastrointestinal (such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), central nervous system, and mental/cognitive disturbances (such as weakness, confusion, disorientation, or delirium).24 The serum digoxin level should be measured at least 6 h after a dose to allow adequate time for equilibration of digoxin between serum and tissue.25,26 Toxicity is more likely to be experienced with digoxin levels above 2.0 µg/L.25,26 Importantly, digoxin serum levels are not reliably correlated with toxicity.27 Thus, a thorough evaluation for clinical parameters of toxicity should always be performed. As hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, or hypomagnesemia may predispose patients to digoxin toxicity, initial laboratory testing for electrolytes and renal function should be performed, and electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected.24,25 These may be repeated if abnormal or as needed in the right clinical context. Maternal electrocardiograms (ECGs) should be obtained to monitor for development of toxicity. The “digitalis effect” on ECG has been well described as a downsloping ST depression with “Salvador Dali sagging”; a flattened, inverted, or biphasic T wave; a shortened corrected QT (QTc) interval; a slight PR interval prolongation; a prominent or inverted U wave.28,29 These changes should be distinguished from signs of toxicity on ECG, which include rhythm abnormalities such as premature ventricular beats, atrial tachycardia, accelerated junctional rhythm/tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation.30 Abnormal conduction including sinus bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and sinus pause, could also represent evidence of maternal digoxin toxicity.30 Digoxin is contraindicated in women with Wolf–Parkinson–White syndrome.2 Indeed digoxin is contraindicated in selective atrioventricular nodal blocks that may facilitate 1:1 anterograde conduction via bypass tract given that in the setting of rapid atrial arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation) this could result in ventricular fibrillation.31 In case of toxicity, a timely diagnosis could lead to effective therapy with digoxin antibody Fab fragments.32 In patients with heart failure, abrupt digoxin discontinuation has been associated with worsening of symptoms; such complications, however, have not been described in otherwise healthy adults.33–35

Although maternally administered digoxin has been considered as the first-line agent for cardioversion of fetal SVT, digoxin is less effective in fetal SVT complicated by hydrops fetalis secondary to poor transplacental transfer.2,8,22 In this setting, alternative or additional agents such as flecainide, sotalol, or amiodarone may be considered.

Flecainide

Flecainide, a class IC antiarrhythmic agent, has also been used for pharmacologic cardioversion of fetal SVT, especially in the setting of hydrops fetalis.19 In healthy nonpregnant subjects orally administered flecainide has 90% bioavailability.36 Peak plasma levels are reached after 2–3 h and steady-state levels are achieved within three to five days, with a half-life ranging from 7 to 23 h.36,37 Although flecainide undergoes some hepatic oxidative metabolism, both flecainide and its metabolites are excreted mostly in the urine.36 Therefore, patients with impaired renal or hepatic function require dose monitoring and dose reduction.36 For the management of fetal SVT, a flecainide dose of 100 mg orally three times a day has been most commonly used.7,18,38 This dose is subsequently adjusted to attain a therapeutic trough level of 0.2–1 µg/mL, and the daily dose should not exceed 600 mg.2,7 Additionally, a treadmill stress test when target dose has been reached may be prudent in order to rule out exercise-induced QRS prolongation.39

Clinical signs of cardiac and noncardiac side effects should be monitored. Noncardiac side effects of flecainide include symptoms of the central nervous system (such as dizziness, vision changes, and headaches) and the gastrointestinal tract (such as constipation, abdominal pain, nausea); cardiac side effects include palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, and peripheral edema.40–42 As the risk of flecainide toxicity increases when trough levels exceed the therapeutic range, maternal serum trough flecainide concentrations can be measured, particularly after dose adjustments. Of note, trough maternal flecainide concentrations, once therapeutic, do not predict cardioversion of fetal SVT.38 Electrocardiographic changes indicating flecainide-induced toxicity include new bundle branch block and prolonged QTc interval ≥0.48 s.5 Some dose-related increases in PR and QRS intervals may be noted on ECG.5,37 Toxicity is, however, suggested by an increase in QRS duration of 50% (0.18 s) and prolongation in PR interval of 30% (0.26 s).43,44 Maternal flecainide toxicity is managed with supportive care and aggressive intravenous bicarbonate administration, with or without intravenous fat emulsion.45 In case of persistent hemodynamic compromise, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be required.46

The landmark “Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial” demonstrated that flecainide was associated with increased mortality and nonfatal cardiac arrest in patients with recent myocardial infarction.47 As a result, its use is contraindicated in patients with recent myocardial infarction and structurally abnormal hearts.48 Since ventricular proarrhythmic effects have also been noted in atrial fibrillation/flutter, it is used with caution in this patient population, and with the addition of an atrioventricular blocking agent.48–50 Flecainide is also contraindicated or used with extreme caution in patients with hypersensitivity to class IC antiarrhythmic agents, bifascicular or second- or third-degree atrioventricular block without pacemaker, and cardiogenic shock.50 Maternal cardiac disease should therefore be actively sought prior to flecainide initiation with a detailed clinical evaluation, and if an underlying structural abnormality is suspected a transthoracic echocardiogram should be performed. Several studies, however, including a systematic review of 30 randomized control trials, a meta-analysis of 122 prospective studies and a nationwide registry in Denmark, have provided compelling evidence that flecainide, given to a selected patient population, was an effective and safe medication.51–54 Thus, with proper maternal monitoring, can be an excellent agent for treatment of fetal SVT especially in the setting of hydrops fetalis.19 At time of therapy completion, no particular measures should be instituted prior to flecainide discontinuation.

Sotalol

Sotalol is a non-cardioselective beta-adrenergic blocker with class III antiarrhythmic properties, which has been used both as first- and second-line therapy for fetal SVT.2 Sotalol is excreted predominantly by the kidneys and caution should be taken in patients with renal impairment.2 Its elimination half-life after oral administration of about 10 h and bioavailability of about 90% do not appear to be significantly altered by pregnancy.55 The suggested sotalol dose for treatment of fetal SVT ranges from 80 to 160 mg twice daily.8,17,56 To minimize the possible risk of maternal adverse events and/or intrauterine death, a dosage scheme with an initiation dose of 80 mg of sotalol twice daily, a stepwise increase by 80 mg every three days, and a maximum daily dose of 480 mg given in three divided doses, has been suggested.56 Others, however, have reported use of higher doses of sotalol.17

Clinical evidence of adverse effects from sotalol therapy includes nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and/or lightheadness.17 Due to the proarrhythmic potential of sotalol, electrolyte levels should be checked, and abnormalities corrected.17 All maternal blood levels should remain below the toxic level of 2.5 mg/L, at which marked prolongation of the corrected QT interval is noted.56 Like flecainide, the effectiveness of sotalol therapy is not to be extrapolated from maternal blood levels.56 Notable maternal ECG changes upon sotalol initiation include P and QRS widening, first-degree atrioventricular block, and QTc of 0.48 s or less.5 Signs of sotalol toxicity include new bundle branch block and QTc greater than 0.48 s.5 Sotalol is contraindicated in or must be used with extreme caution in patients with maternal history of asthma, decompensated heart failure, maternal prolonged QTc interval, and/or maternal bradycardia.57 Therefore, preexisting maternal arrhythmias should be excluded with an extensive history and physical examination, and an ECG should be performed to assess for the QT interval prior to initiation of the medication. Some experts may recommend mandatory inpatient monitoring with continuous ECG for up to three days.48,57 In case of toxicity, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment.58 Additionally, high-dose insulin euglycemia, high-dose glucagon, and hemodynamic support may be considered.58 After therapy completion, the sotalol dose should be weaned over one to two weeks, as abrupt cessation has been linked to angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, hypertension, and arrhythmia.57

Amiodarone

Maternal administration of amiodarone, a class III antiarrhythmic agent, has been shown to be an effective treatment for fetal SVT in the setting of hydrops fetalis or ventricular dysfunction.59 One group described a loading protocol of 1800–2400 mg of oral amiodarone daily for two to seven days in divided doses, followed by continued gradual loading with 800 mg daily for seven days, which was subsequently decreased to the minimal effective dose to maintain sinus rhythm, usually 200–400 mg daily.59 Moreover, digoxin doses were decreased by 50% prior to initiating amiodarone.59 Given that maternal administration of amiodarone has been associated with transient neonatal hypothyroidism in up to 17% of exposed fetuses, and mild neurological abnormalities, its use is thus usually reserved for treatment of severe, refractory, maternal, or fetal arrhythmia.60,61 Nevertheless if amiodarone is chosen as treatment modality, maternal electrolytes and ECG could be monitored daily during loading, and serially during maintenance therapy.59

Amiodarone has complex pharmacologic properties due to its high lipophilicity, its slow elimination rate, and its active metabolites.62 Its bioavailability is 35–65% in healthy, nonpregnant patients, and has a large volume of distribution.62–64 It mostly undergoes hepatic metabolism with minor renal clearance.64 The elimination half-lives of long-term amiodarone therapy and its active metabolite, N-desethylamiodarone, are 20–60 days.62,63 Due to this slow elimination rate, it make take months to achieve steady state.62

Cardiovascular signs of amiodarone toxicity include sinus bradycardia, intraventricular conduction defects, and high-grade heart blocks.64 Moreover, amiodarone prolongs the QT interval and can cause prominent U waves and biphasic T waves.64,65 It has also been associated with torsades de pointes, especially in the setting of hypokalemia.64,65 Accordingly, caution must be exercised when amiodarone is administered to patients with underlying sinus or atrioventricular nodal disease, conduction abnormalities, or in patients taking other medications that may interact with the drug.64 Another serious adverse effect includes amiodarone pulmonary toxicity, manifested as pneumonitis with symptoms of nonproductive cough, dyspnea, weight loss, and fever with associated finding of diffuse interstitial infiltrates on chest radiograph.64 Due to its high iodine content and its structural similarity to thyroxine, amiodarone can lead both to hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism.64 Other less common side effects include neurologic (tremor, ataxia, and peripheral neuropathy), gastrointestinal (nausea, constipation, anorexia, cholestasis, and hepatitis) and dermatologic complications.64

Prior to initiation of amiodarone, a baseline assessment that includes an ECG, a chest radiograph, thyroid and liver laboratory studies, and pulmonary function tests could be considered.65,66 Heart rate, thyroid studies, and liver transaminase levels should be observed at time of amiodarone loading.66 Amiodarone levels do not have to be routinely obtained since they may not correlate with either efficacy or toxicity.59,62 A description of the management of amiodarone-induced toxicity is beyond the scope of this review, and this information can be found in greater detail elsewhere.66,67 Even though amiodarone can be stopped without any tapering regimen, clinicians must bear in mind its long half-life.

Current practices and maternal outcomes

We reviewed current maternal monitoring practices and maternal adverse events during pharmacologic treatment of fetal SVT. We queried the PubMed database with search terms “Fetal” or “Foetal” and “Supraventricular Tachycardia” or “SVT.” There were no limitations on the type of study design included and case reports, case series, cohort studies, case–control studies, and randomized controlled trials were eligible for review. Articles included were reports describing administration maternal treatment for fetal SVT. We excluded articles that exclusively described direct fetal therapy, or articles that did not include any patients with fetal SVT.

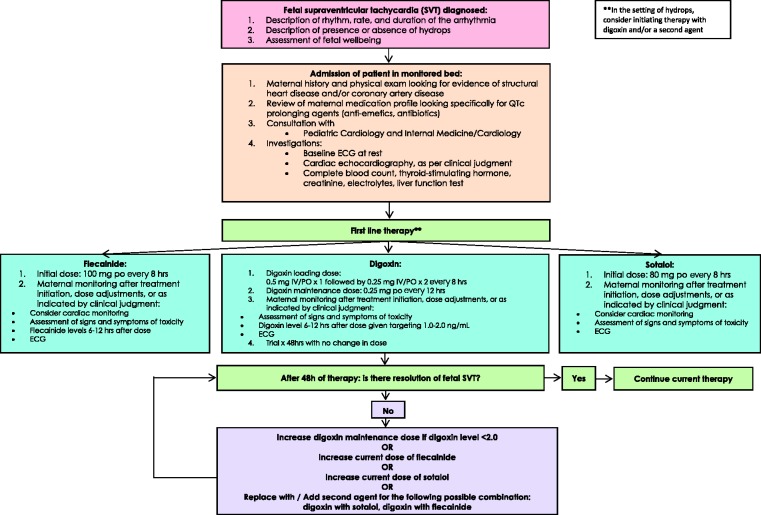

Our initial search yielded 93 titles and abstracts, 19 full-text articles were retained for manual review4,7,13–15,17–21,38,68–75 (Figure 1). This represented a total of 495 cases of fetal SVT, 107 of which had hydrops fetalis. In total, 127 patients received a course of digoxin monotherapy. Flecainide, sotalol, and amiodarone were given as monotherapy in 95, 44, and 6 patients, respectively. Combination therapy with digoxin was given in 122 patients in total using flecainide in 41 patients, sotalol in 55 patients, and amiodarone in 3 patients (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search.

Table 1.

Literature review of reported maternal monitoring practices and adverse events during treatment of fetal supraventricular tachycardia.

| Author, year of publication | CountryStudy period | Study design | Number of cases (n hydrops) | Therapy used (n patients) | Description of maternal monitoring | Reported maternal toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasiah et al.68 | United Kingdom1997–2004 | Case series | 23 (5) | Digoxin (11)Flecainide (2)Digoxin+ flecainide (5)Flecainide and direct fetal therapy (adenosine or amiodarone) (3) | Flecainide levels within 48 hECG at baselineUrea and electrolytes at baseline | None |

| Vautier-Rit et al.21 | France1993–1998 | Case series | 3 (0) | Digoxin (1)Amiodarone (1)Digoxin + amiodarone + intracordal flecainide (1) | NA | NA |

| Dangel et al.69 | Poland | Case report | 2 (2) | Digoxin + intracordal striadyne (2) | General cardiac condition of mothers assessedDigoxin levels checked during antiarrhythmic therapy | NA |

| Suri et al.70 | India | Case report | 1 (1) | Digoxin + sotalol (1) | ECG monitoringElectrolytes monitoring | NA |

| Porat et al.71 | Israel | Case report | 1 (1) | Digoxin + flecainide (1) | NA | NA |

| Husain et al.13 | Bahrain | Case report | 1 (0) | Digoxin (1) | Transthoracic echocardiography at baseline ECG at baseline and during therapyElectrolytes, urea, creatinine at baseline and during therapyDigoxin levels during therapy | Mother with nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain with elevated digoxin level 3.06 mmol/mL. On ECG, normal sinus rhythm (67 bpm) with inverted tick sign. |

| Sridharan et al.18 | United KingdomCzech Republic1987–2012 | Cohort study | 84 (28) | Flecainide (31)Digoxin (31)Flecainide + amiodarone (1)Digoxin + flecainide (2)Digoxin + sotalol (19) | Flecainide:Outpatient therapyECG prior to initiation of therapyFlecainide trough levels if persistent fetal tachycardia or increased doseDigoxin:Electrolytes at baseline and daily during initial phase of treatmentECG at baseline and daily during initial phase of treatmentDigoxin levels daily | Flecainide:7 mothers with lightheadedness, nausea, headache, transient blurry vision.1 mother with Heightened alertness1 mother with toxic trough level when transitioning from flecainide 100 mg q8hrs to q6hrsNo cases required discontinuation of flecainideDigoxin:2 mothers with intolerance |

| Vigneswaran et al.38 | United Kingdom1997–2012 | Case series | 33 (14) | Flecainide (24)Digoxin − flecainide (5)Digoxin + flecainide (2)Flecainide − sotalol + direct intracordal therapy (1)Flecainide − propafenone (1) | Maternal history assessment of palpitations/cardiac diseaseECG at baseline and during follow-upFlecainide trough levels two to seven days after initial therapy and regularly intervals thereafterDigoxin levels measured at least 6 h post-doseMaternal side effects queryInpatient therapy from 1997 to 2002, and outpatient therapy subsequently | Flecainide:1 mother with malaise, palpitations, nausea, flecainide 348 µg/L1 mother with QT prolongation (398 to 560 ms), 20% PR interval (flecainide concentration 814 µg/L) without maternal symptoms |

| Shah et al.17,a | United States2004–2008 | Case series | 29 (8) | Sotalol (9)Sotalol + digoxin (12) | Adult cardiology consultation with considerations for Transthoracic echocardiogramECG through first five doses of sotalolElectrophysiologist reviewing ECG before and after treatment onsetElectrolytes daily during initiation and adjustmentQTc prolonging medications discontinuedNon telemetry bed admission with observation for initiation of therapy | Digoxin + sotalol:4 mothers with nausea, dizziness, fatigue |

| Ekiz et al.19 | Turkey2011–2016 | Case series | 21 (15) | Flecainide (15)Flecainide + digoxin (1)Flecainide + digoxin − sotalol (1) | Adult cardiology consultationDaily maternal ECGIf digoxin given electrolytes, creatinine, and liver enzymes monitored weeklyOnce outpatient, twice weekly monitoring | Flecainide:1 mother with atrial fibrillation leading to discontinuation of flecainide1 mother with dizziness and no flecainide discontinuation |

| Martin-Suarez et al.72 | Spain1997–2015 | Case-series | 8 (1) | Digoxin (5)Digoxin + flecainide (1)Digoxin + sotalol (2) | Digoxin levels during the course of treatmentCreatinine and electrolytes During the course of treatmentECG during the course of treatmentTransthoracic echocardiogram During the course of treatment | None |

| Jouannic et al.73,a | France1990–2000 | Case series | 40 (3) | Digoxin (29)Digoxin − flecainide (1)Sotalol (1)Digoxin + sotalol (2)Digoxin + amiodarone (2)Amiodarone (5) | Clinical assessmentECG | NA |

| Ebenroth et al.14,a | United States1988–1999 | Case series | 40 (10) | Digoxin (22)Digoxin + flecainide (13)Digoxin + propranolol (1)Digoxin + verapamil − Digoxin + propranolol (1) | ECGDigoxin levelFlecainide level when dose greater than 300 mg/day, or when evidence of ECG changes, or when successful SVT control | Digoxin:1 woman on digoxin developed Mobitz type 2, weaned and switched to flecainideFlecainide:Women of the flecainide group demonstrated mild to moderate QRS prolongation, no significant dysrhythmia or adverse effect |

| Oudijk et al.74 | Netherlands, USA 1993–1999 | Case series | 21 (9) | Sotalol (13)Sotalol + dig (7) | ECGMaternal interview for possible history of arrhythmic events | Sotalol:1 patient with temporary nausea1 patient with temporary dizziness and fatigue |

| Ueda et al.4 | Japan2004–2006 | Case series | 52 (10) | Digoxin (11)Digoxin + either flecainide, sotalol, flecainide + sotalol, verapamil (14)Sotalol (2)Propranolol (1) | NA | NA |

| Zhou et al.15 | China2009–2010 | Case series | 4(0) | Digoxin (4) | Maternal vital signsECG dailySerum digoxin concentration every five to seven days | NA |

| Pradhan et al.20 | India | Case report | 1 (1) | Digoxin + amiodarone (1) | Serum digoxin concentration | NA |

| Abraham et al.75 | NA | Case report | 1 (1) | Digoxin - flecainide (1) | NA | NA |

| Jaeggi et al.7,a | United Kingdom, Netherland, Canada1998–2008 | Case series | 159 (6) | Digoxin (12)Digoxin + sotalol (24)Digoxin + flecainide (16)Flecainide (23)Flecainide + amiodarone (1)Sotalol (28)Sotalol + flecainide (7) | In Hospital initiation of therapySerial monitoring of maternal wellbeing, serum electrolytes, cardiac rhythm and ECG | One-third of treated mothers had adverse symptoms including nausea, dizziness for women treated with digoxin/flecainide/sotalolFlecainide:1 woman with visual disturbanceFlecainide + Digoxin:1 woman had therapy stopped × 3 days for low magnesium/potassiumSotalol:1 woman had therapy stopped for symptomatic bradycardia |

aFor selected studies, the numbers reported may include cases of atrial flutter.

Information about maternal monitoring practices was available in 16 studies (Figure 1). Electrocardiograms were performed at baseline and during follow-up in 13 (68.4%) studies, and electrolyte levels were verified in 8 (42.1%). Two studies (10.5%) reported a mandatory consultation with a cardiologist, and three studies (15.79%) considered performing echocardiography in selected mothers. Digoxin levels were done in nine studies (47.37%), and flecainide levels were assessed in four (21.05%).

Table 2 summarizes the frequency of maternal adverse events for monotherapy with a single pharmacologic agent, duel therapy with combination of agents, and sequential therapy by different treatment courses. A detailed description of maternal side effects, when reported, including minor and major events is available on Table 1. Maternal side effects were the most frequent with flecainide monotherapy, as they occurred in 12 (12.6%) patients. One patient developed atrial fibrillation while on flecainide, which spontaneously resolved after treatment cessation.19 Digoxin toxicity was described in two patients. The first developed nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain with digoxinemia of 3.06 mmol/mL.13 Digoxin was withheld for a day and resumed at a lower dose.13 The second developed Mobitz type 2 bradycardia.14 Digoxin was weaned prior to initiating flecainide.14 In both scenario, digoxin cessation was sufficient to treat maternal toxicity and no further reversal therapy was required.13,14 One patient taking a combination of digoxin and flecainide had to suspend therapy because of hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia.7 Mild to moderate increases in QRS without significant dysrhythmia or adverse events were reported in women treated with flecainide.14 As maternal side effects may not have been systematically reported, firm conclusions about their true incidence in this patient population could not be drawn.

Table 2.

Description of maternal side effects and fetal deaths in patients started on monotherapy, dual therapy, and sequential therapy for fetal supraventricular tachycardia.

| Therapy | n | Maternal side effects n (%) | Fetal deathsn (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy (total) | 273 | ||

| Digoxin | 127 | 5 (3.9) | 2 (1.6) |

| Flecainide | 95 | 12 (12.6) | 11 (11.6) |

| Sotalol | 44 | 2 (4.6) | 4 (9.1) |

| Amiodarone | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Propranolol | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dual therapy (total) | 121 | ||

| Digoxin + flecainide | 40 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (2.4) |

| Digoxin + sotalol | 55 | 0 | 2 (3.6) |

| Digoxin + amiodarone | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Digoxin + propranolol | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Flecainide + amiodarone | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Flecainide + sotalol | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Digoxin + either flecainide, sotalol, flecainide + sotalol, verapamil (unspecified) | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Sequential therapy (total) | 101 | ||

| Digoxin − flecainide | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 0 |

| Flecainide − direct fetal therapy | 3 | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Digoxin − amiodarone + intracordal flecainide | 1 | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Digoxin − intracordal striadyne | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Flecainide − propafenone | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Flecainide − sotalol+ intracordal therapy | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Flecainide + digoxin − sotalol | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Digoxin + verapamil − digoxin+ propranolol | 1 | 0 | 0 |

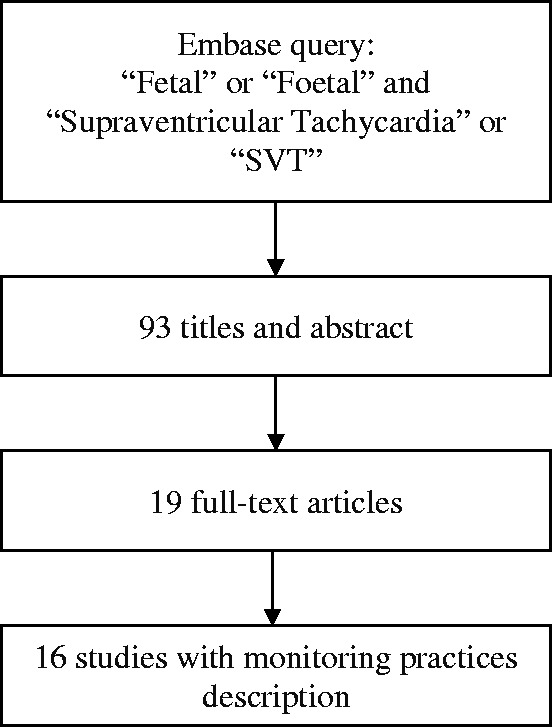

Maternal safety and monitoring protocol during therapy for fetal SVT

In Figure 2, we propose a suggested conservative approach to maternal monitoring aimed at optimizing safety during therapy for women undergoing antiarrhythmic therapy for fetal SVT. In light of previously described proarrhythmic properties of first-line pharmacologic treatments for fetal SVT, it may be prudent to opt for inpatient therapy until stabilization of fetal SVT, after which outpatient treatment could be considered. Continuous cardiac monitoring could also be considered during this time.57 A thorough cardiac history and physical examination aimed at identifying any potential cardiac condition should be performed on all patients at baseline. Medication prolonging QTc should be discontinued. This may include commonly prescribed antiemetic medication such as metoclopramide or chlorpromazine. All women with a known or suspected cardiac condition should be seen in consultation with an adult cardiologist. Baseline ECG, creatinine and electrolytes, and hepatic function testing should be obtained for all patients undergoing therapy. Although some investigators specified that they performed investigations daily—including electrolytes,17,18 ECG,15,18,19 and drug levels18—most authors remained nonspecific about the frequency of testing during follow-up.7,13,14,20,38,69,70,72–74 At a minimum, the signs and symptoms of toxicity, electrolyte abnormalities, and evidence of toxicity on ECG should be sought after initiation of treatment, at time of dose adjustment, or as indicated by clinical judgment. In the absence of resolution of the fetal SVT, doses should be increased or a new agent should replace/be added to the current treatment regimen. At time of delivery and in the postpartum period there should be close communication among members of the interdisciplinary team for both maternal and fetal/neonatal safety.

Figure 2.

Suggested algorithm for maternal safety monitoring during administration of therapy for fetal supraventricular tachycardia.

Conclusion

We described pharmacologic properties and clinical precautions to be held for the most commonly described treatment modalities for fetal SVT. While pharmacologic therapy for management of fetal SVT is generally safe for mothers, careful and informed clinical monitoring should be performed on a daily basis. As there currently are no existing guidelines addressing maternal monitoring during treatment of fetal SVT, we provided clinicians with a suggested treatment protocol aimed at optimizing maternal safety. Future prospective studies on the treatment of fetal SVT should include a thorough description of maternal monitoring practices and maternal adverse reactions in a systematic fashion.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor

KC.

Contributorship

All authors have read and approved the article. All authors listed contributed to drafting and revising this article. All authors have approved of its final version, and all authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Southall DP, Richards J, Hardwick R-A, et al. Prospective study of fetal heart rate and rhythm patterns. Arch Dis Child 1980; 55: 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oudijk MA, Ruskamp JM, Ambachtsheer BE, et al. Drug treatment of fetal tachycardias. Paediatr Drugs 2002; 4: 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweha A, Hacker TW, Nuovo J. Interpretation of the electronic fetal heart rate during labor. Am Fam Phys 1999; 59: 2487–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueda K, Maeno Y, Miyoshi T, et al. The impact of intrauterine treatment on fetal tachycardia: a nationwide survey in Japan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017; 31: 2605–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donofrio MT, Moon-Grady AJ, Hornberger LK, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014; 129: 2183–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson LL. Fetal supraventricular taehycardias: diagnosis and management. Semin Perinatol 2000; 24: 360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaeggi ET, Carvalho JS, De Groot E, et al. Comparison of transplacental treatment of fetal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias with digoxin, flecainide, and sotalol: results of a nonrandomized multicenter study. Circulation 2011; 124: 1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinman CS, Nehgme RA. Cardiac arrhythmias in the human fetus. Pediatr Cardiol 2004; 25: 234–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornberger LK, Sahn DJ. Rhythm abnormalities of the fetus. Heart 2007; 93: 1294–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naheed ZJ, Strasburger JF, Deal BJ, et al. Fetal tachycardia: mechanisms and predictors of hydrops fetalis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 27: 1736–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desilets V, Audibert F. Investigation and management of non-immune fetal hydrops. J Obstetr Gynaecol Canada: JOGC = Journal D'obstetrique et Gynecologie du Canada 2013; 35: 923–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norton ME, Chauhan SP, Dashe JS. Society for maternal-fetal medicine (SMFM) clinical guideline #7: nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 212: 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husain A, Hubail Z, Al Banna R. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia, treating the baby by targeting the mother. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebenroth ES, Cordes TM, Darragh RK. Second-line treatment of fetal supraventricular tachycardia using flecainide acetate. Pediatr Cardiol 2001; 22: 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou K, Hua Y, Zhu Q, et al. Transplacental digoxin therapy for fetal tachyarrhythmia with multiple evaluation systems. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med 2011; 24: 1378–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonesson SE, Fouron JC, Wesslen-Eriksson E, et al. Foetal supraventricular tachycardia treated with sotalol. Acta Paediatrica Int J Paediatr 1998; 87: 584–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah A, Moon-Grady A, Bhogal N, et al. Effectiveness of sotalol as first-line therapy for fetal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 1614–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sridharan S, Sullivan I, Tomek V, et al. Flecainide versus digoxin for fetal supraventricular tachycardia: comparison of two drug treatment protocols. Heart Rhythm 2016; 13: 1913–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekiz A, Kaya B, Bornaun H, et al. Flecainide as first-line treatment for fetal supraventricular tachycardia. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med 2017; 7058: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradhan M, Manisha M, Singh R, et al. Amiodarone in treatment of fetal supraventricular tachycardia: a case report and review of literature. Fetal Diag Therapy 2005; 21: 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vautier-Rit S, Dufour P, Vaksmann G, et al. Arythmies foetales: diagnostic, pronostic, traitement; a propos de 33 cas. Gynecologie Obstetrique et Fertilite 2000; 28: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younis JS. Insufficient transplacental digoxin transfer in severe hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 157: 1268–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitani GM, Steinberg I, Lien EJ, et al. The pharmacokinetics of antiarrhythmic agents in pregnancy and lactation. Clin Pharmacokinet 1987; 12: 253–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanji S, MacLean RD. Cardiac glycoside toxicity. More than 200 years and counting. Crit Care Clin 2012; 28: 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanoxin (digoxin) tablets: manufacturer’s prescribing information, pp. 3–18, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/020405s004lbl.pdf (2009, accessed 28 August 2018).

- 26.Woolf A. Therapy with digoxin-specific antibody fragments. Clin Immunother 1995; 4: 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saad AF, Monsivais L, Pacheco LD. Digoxin therapy of fetal superior ventricular tachycardia: are digoxin serum levels reliable? AJP Rep 2016; 6: e272–e2e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundqvist K, Atterhög JH, Jogestrand T. Effect of digoxin on the electrocardiogram at rest and during exercise in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pick A. Digitalis and the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1957; 15: 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DIGOXIN – Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., 2009, https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=62795623-a2bc-4dd2-8989-3b9782bfd80e (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 31.Sellers TD, Bashore TM, Gallagher JJ. Digitalis in the pre-excitation syndrome. Analysis during atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1977; 56: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang EH, Shah S, Criley JM. Digitalis toxicity: a fading but crucial complication to recognize. Am J Med 2012; 125: 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams KF, Jr., Gheorghiade M, Uretsky BF, et al. Patients with mild heart failure worsen during withdrawal from digoxin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, et al. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: results of the PROVED trial. PROVED Investigative Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 22: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrikopoulos GK. Flecainide: current status and perspectives in arrhythmia management. WJC 2015; 7: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roden DM, Woosley RL. Drug therapy: flecainide. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vigneswaran TV, Callaghan N, Andrews RE, et al. Correlation of maternal flecainide concentrations and therapeutic effect in fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2014; 11: 2047–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razavi M. Safe and effective pharmacologic management of arrhythmias. Texas Heart Inst J 2005; 32: 209–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gentzkow GD, Sullivan JY. Extracardiac adverse effects of flecainide. Am J Cardiol 1984; 53: 101b–105b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hohnloser SH, Zabel M. Short- and long-term efficacy and safety of flecainide acetate for supraventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70: A3–A10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopson JR, Buxton AE, Rinkenberger RL, et al. Safety and utility of flecainide acetate in the routine care of patients with supraventricular tachyarrhythmias: results of a multicenter trial. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77: 72a–82a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: flecainide toxicity. Perm J 2012; 16: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morganroth J, Horowitz LN. Flecainide: its proarrhythmic effect and expected changes on the surface electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol 1984; 53: 89–94b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valentino MA, Panakos A, Ragupathi L, et al. Flecainide toxicity: a case report and systematic review of its electrocardiographic patterns and management. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2017; 17: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devin R, Garrett P, Anstey C. Managing cardiovascular collapse in severe flecainide overdose without recourse to extracorporeal therapy. Emerg Med Australas 2007; 19: 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trial TCAS. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortaliity in randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med 1989; 321: 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 2014: 64e1–6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Apostolakis S, Oeff M, Tebbe U, et al. Flecainide acetate for the treatment of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Exp Opin Pharmacother 2013; 14: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flecainide (Tambocor) Considerations for use, https://www.acc.org/∼/media/Non-Clinical/Files-PDFs-Excel-MS-Word-etc/Tools and Practice Support/Quality and Clinical Toolkits/AFib Toolkit/Flecainide.pdf?la=en (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 51.McNamara RL, Tamariz LJ, Segal JB, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation: review of the evidence for the role of pharmacologic therapy, electrical cardioversion, and echocardiography. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 1018–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wehling M. Meta-analysis of flecainide safety in patients with supraventricular arrhythmias. Arzneimittel-Forschung/Drug Res 2002; 52: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersen SS, Hansen ML, Gislason GH, et al. Antiarrhythmic therapy and risk of death in patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide study. Europace 2009; 11: 886–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aliot E, Capucci A, Crijns HJ, et al. Twenty-five years in the making: flecainide is safe and effective for the management of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2011; 13: 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Hare MF, Leahey W, Murnaghan GA, et al. Pharmacokinetiics of sotalol during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1983; 24: 521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oudijk MA, Ruskamp JM, Ververs FFT, et al. Treatment of fetal tachycardia with sotalol: transplacental pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sotalol (Betapace, Sorine) Considerations for use. American College of Cardiology, https://www.acc.org/tools-and-practice-support/clinical-toolkits/atrial-fibrillation-afib/rate-rhythm-dosing-table/sotalol (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 58.Graudins A, Lee HM, Druda D. Calcium channel antagonist and beta-blocker overdose: antidotes and adjunct therapies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strasburger JF, Cuneo BF, Michon MM, et al. Amiodarone therapy for drug-refractory fetal tachycardia. Circulation 2004; 109: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plomp TA, Vulsma T, de Vijlder JJM. Use of amiodarone during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1992; 43: 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pieper PG. Use of medication for cardiovascular disease during pregnancy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12: 718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roden DM. Pharmacokinetics of amiodarone: implications for drug therapy. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holt DW, Tucker GT, Jackson PR, et al. Amiodarone pharmacokinetics. Am Heart J 1983; 106: 840–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson JS, Podrid PJ. Side effects from amiodarone. Am Heart J 1991; 121: 158–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldschlager N, Epstein AE, Naccarelli G, et al. Practical guidelines for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Practice Guidelines Subcommittee, North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1741–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siddoway LA. Amiodarone: guidelines for use and monitoring. Am Fam Phys 2003; 68: 2189–2196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Papiris SA, Triantafillidou C, Kolilekas L, et al. Amiodarone: review of pulmonary effects and toxicity. Drug Saf 2010; 33: 539–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rasiah SV, Ewer AK, Miller P, et al. Prenatal diagnosis, management and outcome of fetal dysrhythmia: a tertiary fetal medicine centre experience over an eight-year period. Fetal Diagn Ther 2011; 30: 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dangel JH, Roszkowski T, Bieganowska K, et al. Adenosine triphosphate for cardioversion of supraventricular tachycardia in two hydropic fetuses. Fetal Diagn Ther 2000; 15: 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suri V, Keepanaseril A, Aggarwal N, et al. Prenatal management with digoxin and sotalol combination for fetal supraventricular tachycardia: case report and review of literature. Ind J Med Sci 2009; 63: 411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Porat S, Anteby EY, Hamani Y, et al. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia diagnosed and treated at 13 weeks of gestation: a case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin-Suarez A, Sanchez-Hernandez JG, Medina-Barajas F, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosing requirements of digoxin in pregnant women treated for fetal supraventricular tachycardia. Exp Rev Clin Pharmacol 2017; 10: 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jouannic J-M, Delahaye S, Fermont L, et al. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia: a role for amiodarone as second-line therapy? Prenat Diagn 2003; 23: 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oudijk MA, Michon MM, Kleinman CS, et al. Sotalol in the treatment of fetal dysrhythmias. Circulation 2000; 101: 2721–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abraham P. Supraventricular tachycardia with hydrops in a 27-week premature baby. Int J Clin Pract 2001; 55: 569–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]