Short abstract

This pilot study examined the use of early HbA1c in screening for gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Singapore. One hundred and fifty-one pregnant women with a gestational age of under 14 weeks had an HbA1c test measured with their antenatal bloods prior to a second trimester oral glucose tolerance test. Patient characteristics and pregnancy outcome data were collected. Gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence was 11%. A receiver operating characteristic curve showed an HbA1c level of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol), had an 82% sensitivity, 72% specificity, 97% negative predictive value and 27% positive predictive value to predict gestational diabetes mellitus. Women with HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or over 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) were older, had higher BMI and were less likely to be Chinese than those with HbA1c less than 5.2% (33 mmol/mol). There was no difference in pregnancy outcomes. Early HbA1c less than 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) may be useful to exclude low-risk Singaporean women from further testing, while those with HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or greater would still need a oral glucose tolerance test between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Keywords: HbA1c, gestational diabetes mellitus

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as the first presentation of hyperglycaemia or glucose intolerance in pregnancy, is one of the most common antenatal medical disorders.1 The diagnosis of GDM was initially made to identify women at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus following pregnancy.2 However, it is now well established that women with GDM are at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes including operative deliveries, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, fetal macrosomia and shoulder dystocia.3 This was demonstrated by the Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study which suggested a linear relationship between increasing glycaemia levels and poor pregnancy outcomes.2 A recent study in early 2018 has also shown that these women are at increased risk of developing ischaemic heart disease and hypertension in the future.4

The prevalence of GDM at Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH), the largest maternity hospital in Singapore, has increased significantly from 2.8% in 1994, when screening was risk based and diagnosis made using the WHO oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) criteria,5 to 15% in 2016 following the adoption of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) criteria and universal screening.6,7

While the OGTT is considered the gold standard diagnostic test for GDM, there are drawbacks which limit patient acceptance and compliance, such as the need for an overnight fast and subsequently having to ingest a glucose drink that some women find unpalatable, with further blood taking over the next 2 h.8

Performing a single haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) might be an attractive alternative to the OGTT as an additional risk stratification tool in otherwise low-risk women, as it does not require fasting or a glucose drink and can be combined with the other blood tests at the initial antenatal booking screen.

In recent years, HbA1c has mainly been used to screen for pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy; an HbA1c threshold of 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or over has been endorsed by IADPSG and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to diagnose pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy.6,9 One of the reasons for the lack of consensus on reference range of HbA1c in pregnancy to screen for pre-diabetes or GDM is that HbA1c levels fluctuate with each trimester. It is thought that HbA1c levels fall in late pregnancy due to the decreased erythrocyte lifespan along with associated physiological anaemia in pregnancy.10–12 Several studies have demonstrated that HbA1c is generally lower in pregnant compared to non-pregnant individuals.13–15 However, two studies from Japan have suggested that there is no significant difference in HbA1c in the first trimester compared to the non-pregnant state.16,17

In contrast to the first trimester, there may be a range of physiological factors that could undermine the reliability of HbA1c measurement in the second and third trimesters to predict adverse materno-fetal outcomes. For instance, HbA1c does not capture postprandial fluctuations in later pregnancy,3 therefore it may be a less reliable predictor of glucose intolerance. In addition, conditions such as haemoglobinopathies and iron deficiency anaemia may produce falsely low glycated haemoglobin levels. Racial and ethnic differences have also been reported to affect HbA1c levels.18

However, several studies have supported the use of early HbA1c testing to predict adverse pregnancy outcomes. A New Zealand study examining over 8000 women suggested that a first trimester HbA1c of 5.9% (41 mmol/mol) or over was 98% specific although less sensitive at 18% to detect GDM; it is also associated with more than two-fold increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as pre-eclampsia, shoulder dystocia and perinatal mortality.19 Another study from Switzerland demonstrated that women diagnosed with GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation had a significantly higher first trimester mean HbA1c levels of 5.4% (36 mmol/mol) than those who did not develop GDM with HbA1c 5.2% (34 mmol/mol).20 Similarly, a retrospective study from the United States concluded that a first trimester HbA1c in the pre-diabetic range of 5.7–6.5% (39–48 mmol/mol) was associated with a higher rate of GDM although its sensitivity for detection was low at 13%.21 Another study from Barcelona demonstrated women with a first trimester HbA1c of 5.9% (41 mmol/mol) or over were three times more likely to develop pre-eclampsia and have macrosomic babies.22

To our knowledge there is no reported study examining the role of early pregnancy HbA1c among women in Southeast Asia. We therefore conducted a local pilot study to determine the optimal threshold of early pregnancy HbA1c that could best identify GDM based on the IADSPG OGTT criteria. In addition, we wanted to examine if this HbA1c threshold was associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in our local population of mixed ethnic Singaporean women, which could then be validated by a future larger study.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted in KKH, the largest maternity unit in Singapore, from June 2016 to June 2017. There are currently more than 12,000 births per year at our unit. Based on sample size calculation with GDM prevalence rate of 15% in our local population, and sensitivity of HbA1c set at 90% with attrition rate of 20%, we would have had to recruit 1150 patients. Due to resource constraints, we conducted a pilot study involving 150 women to look at the findings before proceeding with a future larger study to verify the results.

Pregnant women attending KKH antenatal clinics at less than 14 weeks’ gestation were recruited at their booking visit. Women with multiple pregnancies, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, known haemoglobinopathies such as thalassaemia or other chronic medical conditions including chronic kidney or liver disease, which alter red cell survival, were excluded from the study. Women are routinely screened for beta-thalassaemia with haemoglobin electrophoresis in their antenatal blood tests at KKH. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients recruited in the study. The study was approved by the Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board in 2016, Ref 2016/2043.

All study participants had an HbA1c test added to their routine antenatal bloods performed at their booking visit. HbA1c samples were processed in our Biochemistry laboratory in KKH using Abbott Architect HbA1c enzymatic assay on Abbott Architect C8000 analyser. Architect HbA1c calibrators are traceable to the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry reference method for HbA1c and are certified by the National Glycoprotein Standardization Program to ensure alignment with the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial.23

Height and weight were measured without shoes using a height and weight digital scale (Avalanche Mechtronics, model B1000-M, Singapore) in the antenatal clinics. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Other baseline patient characteristic data including parity, family history of diabetes and previous history of GDM were collected in the form of an interviewer-administered questionnaire at point of recruitment.

The women then underwent universal screening by 3-point OGTT between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation. Participants had to report after an overnight fast to have their venous fasting plasma glucose (FPG) taken, followed by 1 and 2 h plasma glucose after a 75 g glucose drink. All plasma glucose samples were also analysed in our Biochemistry laboratory in KKH for standardisation purposes with the use of colorimetry in ADVIA 2400 Chemistry system (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics). GDM was diagnosed by the IADPSG criteria: FPG ≥ 5.1 mmol/l or 1 h glucose ≥10.0 mmol/l or 2 h glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/l.6

Pregnancy outcome data were collected from delivery and birth record forms in KKH labour ward, looking specifically at outcomes of gestation at delivery, mode of delivery, development of gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia, birthweight, APGAR scores and if the newborn required neonatal intensive care admission. Large for gestational age was defined as birthweight over the 90th centile, which was greater than 3500 g at term for Southeast Asian babies while small for gestational age was defined as birthweight under the 10th centile, which was equivalent to less than 2500 g at term for Southeast Asian babies.24 Gestational hypertension was defined as blood pressure of ≥140/90 mmHg after 20 weeks’ gestation in a previously normotensive woman, while pre-eclampsia was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg with proteinuria of more than 0.3 g protein/24 h and/or other maternal organ dysfunction.25 Women who dropped out of the study due to early miscarriage or elective termination of pregnancy or defaulted OGTT or transferred to another hospital for delivery were excluded from the final analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using the R software with the involvement of a statistician. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted using sensitivity against 1-specificity to assess the optimal diagnostic threshold of HbA1c against GDM diagnosed by the IADPSG criteria. The Student’s t-test and Pearson’s chi-square test were used to compare patient characteristics and pregnancy outcomes as appropriate. Pregnancy outcomes were expressed in terms of relative risk with 95% confidence intervals. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

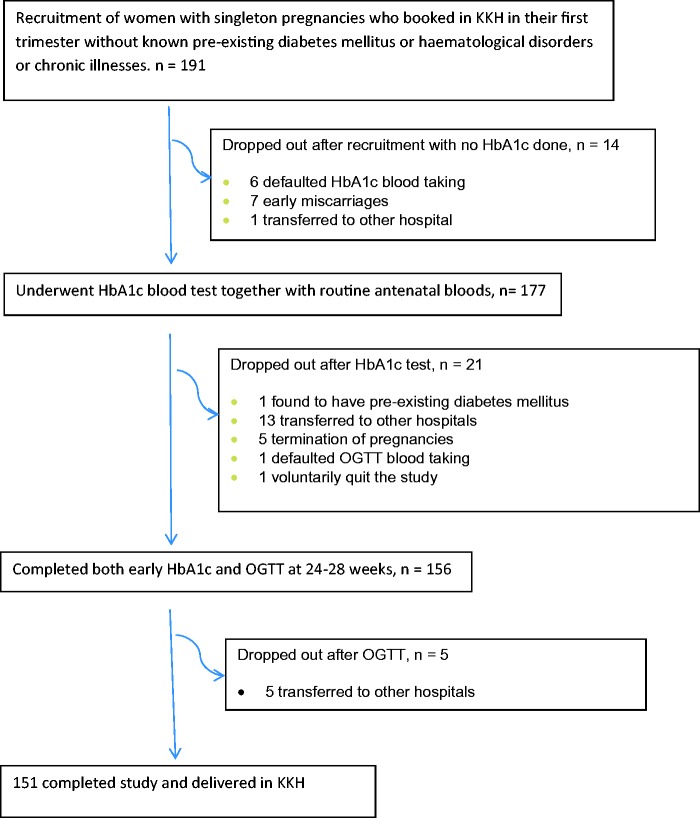

One hundred and ninety-one women were initially recruited over a 12-month period from 2016 to 2017. One hundred and seventy-seven had an HbA1c test added to their routine antenatal bloods at booking visit up to the 14th week of gestation. One patient was found to have pre-existing diabetes, with an HbA1c of 7.6% (60 mmol/mol) and was excluded from the study. Another 20 patients, who had their HbA1c test done, were excluded from the study due to transfer to another hospital, elective termination of pregnancy or failure to complete their OGTT at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation. A further five patients who completed both HbA1c and OGTT were dropped from the study due to transfer to other hospitals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment of study subjects at KK Hospital. HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c; KKH: Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test.

A total of 151 women were included in the final analysis. The range of HbA1c level was 4.2 to 6.0% (22–42 mmol/mol). A comparison between patients included in the final analysis (having completed both HbA1c and OGTT and delivered in KKH) versus those excluded (due to transfer, elective termination or failure to complete OGTT) showed no difference in their mean HbA1c, age and BMI.

Seventeen women out of the 151 developed GDM as defined by the IADPSG criteria between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation, with an overall prevalence of 11.3%. Seventy-four women were Chinese (49%), 47 were Malay (31%), 16 were Indian (11%) and 15 were Eurasian/other races (10%).

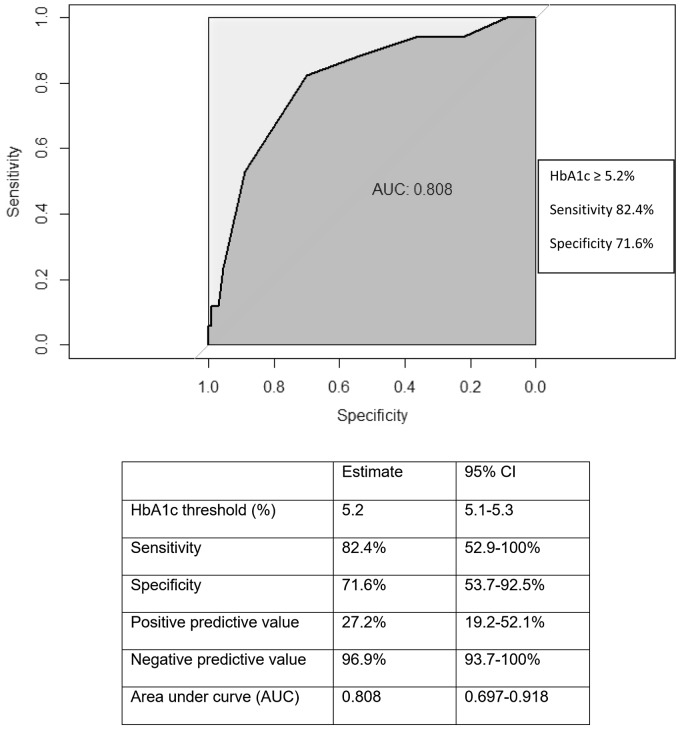

A ROC curve constructed using the IADPSG GDM criteria as reference showed an early pregnancy HbA1c level of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) (95% CI 5.1–5.3%), had a sensitivity of 82.4% (95% CI 52.9–100%) and specificity of 71.6% (95% CI 53.7–92.5%) to predict GDM, with an area under the curve of 0.81 (95% CI 0.697–0.918) (Figure 2). It also has a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.9% (95% CI 93.7–100%) and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 27.2% (95% CI 19.2–52.1%) to predict GDM.

Figure 2.

ROC curve of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) for diagnosis of gestational diabetes using IADPSG diagnostic criteria as reference. IADPSG: International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group.

Using this HbA1c cut-off of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol), a baseline comparison of the characteristics and demographics of women who had an HbA1c above and below this level (54 women and 97 women respectively) was made regardless of their GDM diagnosis (Table 1). Women in the higher HbA1c group were significantly older and had a higher BMI. There was also a greater relative proportion of Indians and Eurasians in the higher HbA1c group compared to the lower HbA1c group. There was no difference in terms of parity, family history of diabetes or previous history of GDM between groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient demographics according to early HbA1c measurement done in the first trimester up to 14 weeks’ gestation.

| Maternal demographicsn = 151 | HbA1c <5.2%(<33 mmol/mol)n = 97 | HbA1c ≥5.2%(≥33 mmol/mol)n = 54 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean) | 29 | 32 | 0.0003 |

| Booking BMI (kg/m2) (mean) | 23.6 | 25.7 | 0.01 |

| Nulliparous status | 57 (58.7%) | 26 (48.2%) | 0.28 |

| Multiparous (Para ≥1) | 40 (41.2%) | 28 (51.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Chinese | 49 (50.5%) | 24 (44.4%) | 0.001 |

| Malay | 37 (38.1%) | 10 (18.5%) | |

| Indian | 4 (4.1%) | 12 (22.2%) | |

| Eurasian/Others | 7 (7.2%) | 8 (14.8%) | |

| Family history of diabetes | 35 (36.1%) | 26 (48.2%) | 0.20 |

| Previous GDM | 3 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.49 |

BMI: body mass index; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c.

With regard to perinatal outcomes such as operative deliveries including assisted vaginal delivery and caesarean section, as well as gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia and low birthweight, there was no difference found among women with an HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or more compared to those with HbA1c less than 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pregnancy outcomes according to early pregnancy HbA1c measurements taken up to 14 weeks’ gestation.

|

HbA1c <5.2%(<33 mmol/mol)n = 97 |

HbA1c ≥5.2%(≥33mmol/mol)n = 54 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy outcomes n = 151 | n (%) | n (%) | RR (95% CI) |

| Preterm delivery <37 weeks’ gestation | 10 (10.3%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0.78 (0.33, 1.84) |

| Assisted delivery | 6 (6.2%) | 4 (7.4%) | 1.13 (0.51, 2.48) |

| Caesarean section | 29 (29.8%) | 19 (35.2%) | 1.16 (0.75, 1.81) |

| Gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia | 4 (4.1%) | 3 (5.6%) | 1.21 (0.50, 2.92) |

| Small for gestational age (SGA) <10th centile, i.e. <2500 g | 7 (7.2%) | 7 (12.9%) | 1.46 (0.82, 2.58) |

| Large for gestational age (LGA) >90th centile, i.e. >3500 g | 17 (17.5%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0.49 (0.19, 1.22) |

| Neonatal ICU admission | 4 (4.1%) | 3 (5.6%) | 1.21 (0.50, 2.90) |

| Apgar scores <7 at 1 min or 5 min | 2 (2.1%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.93 (0.18, 4.67) |

HbA1c: haemoglobin A1c; RR: Relative Risk (RR).

Discussion

In this pilot study, we demonstrated that a first trimester HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or more had a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 72% as well as NPV of 97% for the detection of GDM among Singaporean women.

Recently, several other studies in mainly Caucasian populations have examined the use of HbA1c measurement in early pregnancy as a screening tool for GDM in place of the traditional OGTT.19,21,26–28 A North American study demonstrated an early pregnancy level of HbA1c greater than 5.7% (39 mmol/mol) could detect women at significantly higher risk of developing GDM.21 Similarly, a Norwegian study suggested a first trimester HbA1c cut-off of 5.6% (36 mmol/mol) could be used to screen for GDM among pregnant Caucasian women with polycystic ovary syndrome.26

Our findings differ from these studies with a lower HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol). We postulate that the lower HbA1c level found in our Singaporean population may be related to ethnic differences in HbA1c as it is known that there are genetic variations in the degree of glycosylation of haemoglobin, independent of degree of glycaemia between ethnic groups. For instance, two studies have demonstrated that African Americans have higher HbA1c levels than their white Caucasian counterparts across a range of glucose levels although the reason for this remains unknown.29,30

Racial differences in HbA1c have also been reported in Singapore. A local study involving men and non-pregnant women suggested that the relationship between FPG and HbA1c differs between the three major ethnic groups (Chinese, Malay and Indian) in Singapore.31 So, for a fasting glucose of 5 mmol/l, the HbA1c level was higher among Malays and Indians than among the Chinese. This difference persisted even after adjusting for age, gender, BMI and other markers of insulin resistance, with an HbA1c difference of 0.19% (2.1 mmol/mol) between Indians and Chinese, and a 0.24% (2.6 mmol/mol) difference between Malays and Chinese for a similar fasting glucose level of 7.0 mmol/l.31 This could possibly explain the relatively higher proportion of Indian women in our study with an HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or over and account for the overall lower HbA1c level to detect GDM in our predominantly Chinese population.

On the other hand, while we did not find any differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes, other studies have demonstrated the association of HbA1c with adverse outcomes. A study in Brazil showed that women with an HbA1c over 5.9% (41 mmol/mol) had a three-fold increased risk of having a macrosomic baby as well as developing pre-eclampsia.22 Another recent study in Taiwan demonstrated that a mid-trimester HbA1c over 5.0% (42 mmol/mol) is significantly associated with adverse outcomes including pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery and macrosomia.32 Several other studies have also found a correlation between increasing maternal HbA1c levels and fetal macrosomia, independent of GDM diagnosis.13,33,34

The use of HbA1c as a screening tool for GDM is still a contentious issue due to its low sensitivity and specificity seen in studies. The HAPO study showed that HbA1c had a poorer correlation with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to glucose levels, concluding that HbA1c is not a useful alternative to OGTT.35 Osmundson et al. demonstrated that an early HbA1c of >5.7% (>39 mmol/mol) had a sensitivity of only 13% to predict GDM.21 Similarly, a Spanish study concluded that a first trimester HbA1c value of 5.6% (38 mmol/mol) with a sensitivity of 33% and a PPV of 32% was inadequate to diagnose GDM.36

In comparison, although our study demonstrates that early HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or over has a relatively high sensitivity (82%) and specificity (72%) to detect GDM, it is still inadequate to replace OGTT as a screening test for GDM due to its low PPV of 27%. It may however be useful as an adjunct tool to exclude low-risk women from further testing given its high NPV of 97%. The advantages of employing an early pregnancy HbA1c lie in its convenience, ease of testing and lower cost, resulting in a higher likelihood of compliance to performing the test compared to an OGTT.

To our knowledge, there is no published data evaluating the use of early pregnancy HbA1c among low-risk Southeast Asian Singaporean women as a screening tool for GDM and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes; our study is the first to address this issue. Although other studies included populations with Asian background, they cannot be directly compared to our study as they were looking at the HbA1c measured in the second or third trimesters.32,37–40 As previously discussed HbA1c measured later in pregnancy is less likely to be physiologically reliable.3,10–12

However, we recognise there are several limitations to our study. First, we are unable to exclude women with alpha-thalassaemia and other haemoglobinopathies, although all pregnant patients are routinely screened for beta-thalassaemia at booking antenatal bloods. Second, as this is a pilot study, it is not powered to detect a significant difference in early HbA1C measurement in association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. This is despite growing evidence as mentioned above to suggest HbA1c may be used to predict adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a first trimester HbA1c of less than < 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) may be useful as an additional screening tool to exclude low-risk Singaporean women from further testing of GDM in later pregnancy, while those with HbA1c of 5.2% (33 mmol/mol) or over would likely still need a confirmatory OGTT between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation. This hypothesis could be elucidated further with a larger study to verify the findings of our pilot study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nicole Lee, research manager, as well as Estella Wang, clinical research coordinator, in Maternofetal Medicine Department at KK Hospital, for helping in patient recruitment and coordination of study participants’ appointment visits. We are also thankful to Clement Ho, Head of Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and Johnson Setoh, lab technician for analysis of blood samples for HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance tests.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the 4th Singhealth Duke-NUS OBGYN Academic Clinical Program Grant awarded in 2016.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) in 2016, Reference 2016/2043. Written informed consent was obtained from patients for publication.

Guarantor

ZXP will be the guaranteeing author for this paper to guarantee the manuscript’s accuracy and the contributorship of all co-authors.

Contributorship

We declare that all the above listed authors have:

made a substantial contribution to the concept, analysis and interpretation of the study data

drafted and revised the article for important intellectual content

taken responsibility for the appropriate portions of the content

approved the version to be published

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013, p.3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, et al. Hyperglycaemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1991–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. Management of diabetes in pregnancy. Sec. 13. In standards of medical care in diabetes 2017. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: S114–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly B, Toulis KA, Thomas N, et al. Increased risk of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus, a target group in general practice for preventive interventions: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med 2018; 15: e1002488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan KT, Tan KH. Pregnancy and delivery in primigravidae aged 35 and over. Singapore Med J 1994; 35: 495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh SD, Tan JW, Chern BS, et al. Universal screening versus targeted screening for gestational diabetes mellitus at a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.1002/uog.16774 (EPub 8 September 2016).

- 8.Buckley BS, Harreiter J, Damm P, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Europe: prevalence, current screening practice and barriers to screening. A review. Diabet Med 2012; 29: 844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Diabetes in Pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. London NICE; Feb 2015. [nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3]. [PubMed]

- 10.International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1200–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurie S, Danon D. Life span of erythrocytes in late pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 80: 123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Versantvoort AR, van Roosmalen J, Radder JK. Course of HbA1c in non-diabetic pregnancy related to birth weight. Neth J Med 2013; 71: 22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor C, O’Shea PM, Owens LA, et al. Trimester-specific reference intervals for haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in pregnancy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012; 50: 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Qi X, Wang X. Application of glycated hemoglobin in the perinatal period. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014; 7: 4653–4659. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki S, Takeuchi T. HbA1c levels in Japanese women during early pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2005; 273: 174–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiramatsu Y, Shimizu I, Omori Y, et al. Determination of reference intervals of glycated albumin and haemoglobin A1c in healthy pregnant Japanese women and analysis of their time courses and influencing factors during pregnancy. Endocr J 2012; 59: 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.William HH, Robert MC. Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose: implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 1067–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes RC, Moore MP, Gullam JE, et al. An early pregnancy HbA1c ≥5.9% (41 mmol/mol) is optimal for detecting diabetes and identifies women at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: P2953–P2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amylidi S, Mosimann B, Stettler C, et al. First-trimester glycosylated hemoglobin in women at high risk for gestational diabetes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016; 95: 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osmundson SS, Zhao BS, Kunz L, et al. First trimester hemoglobin A1c prediction of gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol 2016; 33: 977–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mane L, Roux JAF, Benaiges D, et al. Role of first-trimester HbA1c as predictor of adverse obstetric outcomes in a multi-ethnic cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102: 390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teodoro-Morrison T, Janssen M, Mols J, et al. Evaluation of a next generation direct whole blood enzymatic assay for hemoglobin A1c on the ARCHITECT c8000 chemistry system. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 53: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray J, Sgro M, Mamdani MM, et al. Birth weight curves tailored to maternal world region. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012; 34: 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014; 4: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odsaeter IH, Asberg A, Vanky E, et al. Hemoglobin A1c as screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in Nordic Caucasian women. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2016; 8: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Punnose J, et al. Gestational diabetes screening of a multi-ethnic, high-risk population using glycated proteins. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2001; 51: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhavadharini B, Mahalakshmi MM, Deepa M, et al. Elevated glycated haemoglobin predicts macrosomia among Asian Indian pregnant woman (WINGS-9). Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2017; 21: 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Weintraub WS, et al. Glucose-independent, black–white differences in hemoglobin A1c levels: a cross-sectional analysis of 2 studies. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152: 770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvin E, Steffes MW, Ballantyne CM, et al. Racial differences in glycemic markers: a cross-sectional analysis of community-based data. Ann Intern Med 2011 March; 154(5): 303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkataraman K, Kao SL, Thai AC. Ethnicity modifies the relation between fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c in Indians, Malays and Chinese. Diabetes Med 2012; 29: 911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho YR, Wang P, Lu MC, et al. Associations of mid-pregnancy HbA1c with gestational diabetes and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in high-risk Taiwanese women. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0177563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subash S, et al. HbA1c level in last trimester pregnancy in predicting macrosomia and hypoglycemia in neonate. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2016; 3: 1334–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikkelsen MR, Nielsen SB, Stage E, et al. High maternal HbA1c is associated with overweight in neonates. Dan Med Bull 2011; 58: A4309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Dyer AR, et al. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study – associations of maternal A1C and glucose with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benaiges D, Flores-Le Roux JA, Marcelo I, et al. Is first-trimester HbA1c useful in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017; 133: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye M, Liu YY, Cao XP, et al. The utility of HbA1c for screening gestational diabetes mellitus and its relationship with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016; 114: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon SS, Kwon JY, Park YW, et al. HbA1c for diagnosis and prognosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 110: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renz PB, Gabriela C, Letícia SW, et al. HbA1c test as a tool in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soumya S, Rohilla M, Chopra S, et al. HbA1c: a useful screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015 Dec; 17(12): 899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]