Abstract

Background

As more patients are surviving intensive care, mental health concerns in survivors have become a research priority. Among these, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can have an important impact on the quality of life of critical care survivors. However, data on its burden are conflicting. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the prevalence of PTSD symptoms in adult critical care patients after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, Web of Science, PsycNET, and Scopus databases from inception to September 2018. We included observational studies assessing the prevalence of PTSD symptoms in adult critical care survivors. Two reviewers independently screened studies and extracted data. Studies were meta-analyzed using a random-effects model to estimate PTSD symptom prevalence at different time points, also estimating confidence and prediction intervals. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore heterogeneity. Risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool and the GRADE approach.

Results

Of 13,267 studies retrieved, 48 were included in this review. Overall prevalence of PTSD symptoms was 19.83% (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.72–23.13; I2 = 90%, low quality of evidence). Prevalence varied widely across studies, with a wide range of expected prevalence (from 3.70 to 43.73% in 95% of settings). Point prevalence estimates were 15.93% (95% CI, 11.15–21.35; I2 = 90%; 17 studies), 16.80% (95% CI, 13.74–20.09; I2 = 66%; 13 studies), 18.96% (95% CI, 14.28–24.12; I2 = 92%; 13 studies), and 20.21% (95% CI, 13.79–27.44; I2 = 58%; 7 studies) at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months after discharge, respectively.

Conclusion

PTSD symptoms may affect 1 in every 5 adult critical care survivors, with a high expected prevalence 12 months after discharge. ICU survivors should be screened for PTSD symptoms and cared for accordingly, given the potential negative impact of PTSD on quality of life. In addition, action should be taken to further explore the causal relationship between ICU stay and PTSD, as well as to propose early measures to prevent PTSD in this population.

Trial registration

PROSPERO, CRD42017075124, Registered 6 December 2017.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13054-019-2489-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Critical care, Intensive care units, Meta-analysis, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Prevalence, Systematic review

Background

Mortality in critical care has steadily declined in recent decades [1, 2]. As a result, concerns about long-term outcomes and quality of life in critical care survivors have become a priority. Recently, more attention has been given to the psychiatric consequences of acute illness in the intensive care unit (ICU), especially in young patients. Psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are known to have a strong impact on the quality of life in long-term ICU survivors [3].

PTSD is characterized by having been exposed to an event that is life-threatening or perceived as life-threatening and, subsequently, developing intrusive recollections of the event, hyperarousal symptoms, and avoidant behavior related to the traumatic event [4]. Negative changes in cognition and mood are often part of the clinical picture of PTSD. The classical notion of PTSD as a reaction to warfare or natural disasters has been recently extended to include reaction to road traffic accidents, sexual assaults, and medical conditions such as critical care admission [5]. However, the burden of PTSD associated with critical illness remains unclear.

An in-depth understanding of the current prevalence, risk factors, and accuracy of diagnostic tools is essential to establish early interventions aiming to prevent or minimize PTSD after ICU admission [6]. Prevalence estimates of PTSD among ICU survivors have ranged widely from 4 to 62% [7]. This variability seems to be dependent on the time of PTSD assessment, instrument used, and population studied [7].

Although previous systematic reviews of PTSD prevalence among ICU survivors have been published, there has been increasing interest in this topic in the last few years, and the literature on PTSD in survivors of critical illness has expanded substantially. Moreover, there has been an improvement in methods used for pooling prevalence estimates and interpreting their results. Therefore, given the absence of recent reviews on this topic, we designed the present systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the overall prevalence of PTSD in adult survivors of critical care.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual [8] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement [9, 10]. The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42017075124).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined based on the Condition, Context, Population (CoCoPop) framework, as follows: (1) observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies, or case series) published as full-text articles, (2) context—patients who survived critical care admission, (3) condition—prevalence of PTSD symptoms after ICU discharge, and (4) population analyzed—adult critical care survivors (age ≥ 18 years). We excluded studies that did not report sufficient data to estimate PTSD prevalence, review articles, letters to the editor or comments, studies evaluating neonatal/pediatric critical care units, and studies evaluating patients admitted for acute neurological diseases.

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, LILACS, Web of Science, PsycNET, and Scopus databases from inception to September 2018. In addition, we reviewed the reference lists of previous systematic reviews covering the same research question [7, 11, 12]. No language restrictions were imposed. The following search terms were used for all databases: critical care, intensive care units, critical illness, sepsis, and adult respiratory distress syndrome, which were cross-referenced to the terms outcome, follow-up, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The complete search strategies used for all databases are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Study selection

Two reviewers (CR and RTAS) independently screened titles and abstracts identified by the initial search. The full text of potentially relevant articles was obtained to determine whether the studies met the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the reference lists of the selected articles were hand-searched to detect any additional studies that had not been identified by the initial electronic search. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus or by involving a third reviewer (FAB) for arbitration.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (CR and RTAS) independently extracted data from the selected articles, recording the following information if available: (1) study characteristics (location, period of enrollment, criteria for enrollment, number of patients enrolled, population characteristics, duration of follow-up), (2) study design, (3) reason for ICU admission, (4) number of patients evaluated/observed, (5) instrument used for PTSD assessment, (6) prevalence of PTSD after ICU discharge, and (7) time elapsed from discharge to assessment. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus among the reviewers (CR, RTAS, FAB). If data were not reported, we contacted the corresponding authors by email.

Outcomes

The main outcome of interest was the prevalence of PTSD in adult survivors of critical care at different time points after ICU discharge. The diagnosis of PTSD was considered according to each individual study definition.

Assessment of study quality

We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data [13]. This checklist contains 9 questions, which we divided into 3 domains: participants (questions 1, 2, 4, and 9), outcome measurement (6 and 7), and statistics (3, 5, and 8). A study was rated as having high quality when the methods were appropriate in all 3 domains.

We used the GRADE approach to assess the overall quality of evidence [14]. In the absence of a formal procedure for the assessment of certainty in prevalence estimates, we applied the framework developed for incidence estimates in the context of prognostic studies [15].

Statistical analysis

We pooled the prevalence estimates from included studies using a random-effects meta-analysis model with the DerSimonian and Laird variance estimator. Prevalence estimates were transformed using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation so that the data followed an approximately normal distribution. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic. Since prevalence estimates vary in different settings due to several factors, such as different patient and ICU characteristics, we also estimated prediction intervals to provide a range of expected PTSD prevalence in different settings [16].

Data from the longest follow-up available in each study were used to estimate the overall prevalence. We performed subgroup analyses to assess whether the method used to diagnose PTSD (screening instrument alone or clinical assessment) and the time point of PTSD assessment (< 3, 3, 6, 12, or > 12 months after ICU admission or discharge) influenced our pooled estimate. We also performed a meta-regression analysis to explore the association between PTSD prevalence estimates and two variables: mean participant age and percentage of respondents in each study. We did not perform a meta-regression analysis for time point of PTSD assessment as a covariate, because we did not expect it to have a linear association with PTSD prevalence.

Results are presented in forest plots with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) or scatter plots with point estimates and 95% CI. All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 3.4.4 (R Development Core Team, 2008), with package meta version 4.8-1 [17] and package ggplot2 version 2.2.1 [18].

Results

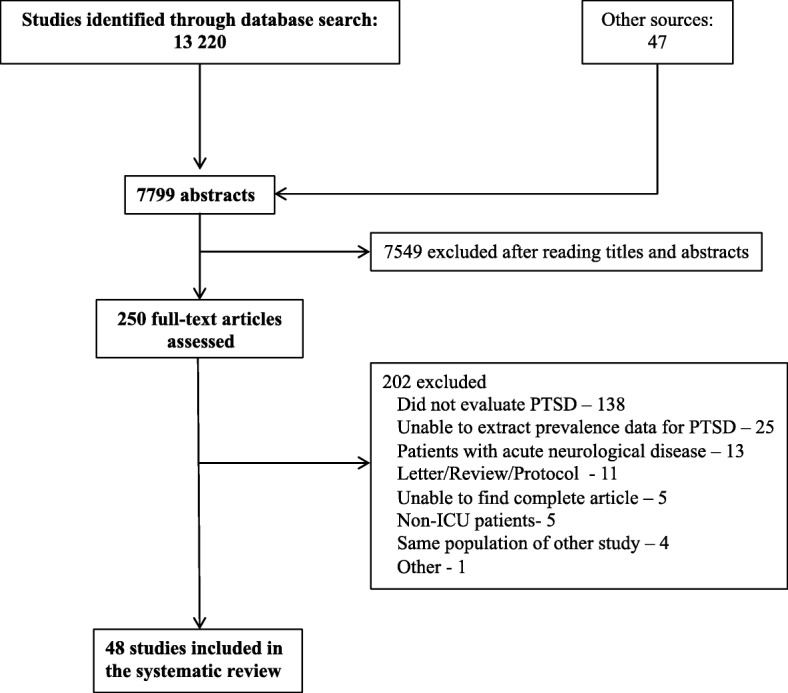

Of 13,267 records identified, 250 studies were selected for full-text assessment (Fig. 1). Of these, 48 studies enrolling a total of 7152 patients were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis [3, 6, 19–64].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The time span of the studies was from 1996 to 2018. Most studies were conducted in mixed ICUs (16 studies), followed by medical ICUs (13 studies), trauma ICUs (5 studies), surgical ICUs (3 studies), and long-term and cardiac ICUs (2 studies each). Ten studies did not report the type of ICU involved. The mean age of enrolled patients ranged from 36.5 to 68.0 years; 27 studies reported a male predominance. Except for 4 studies conducted in Australia [20, 25, 33, 62], 2 conducted in Latin America [24, 29], 1 study conducted in Iran [22], and 4 studies in which location was not reported [30, 41, 46, 57], all other studies (77%) were conducted in the USA or Europe.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Study period | Location | Type of ICU | No. of patients | Age, mean ± SD | Male sex, n (%) | PTSD prevalence, n (%) | Instrument of assessment | Time of assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al. [19] | Not reported | USA | Trauma ICU | 115 | 42.4 ± 16.7 | 64 (55.7%) | 30 (26%) | DTS | 1 year after hospital discharge |

| Aitken et al. [20] | May 2014–April 2015 | Australia | Not reported | 57 | 53.7 ± 14.8 | 37 (65%) | 7 (12.3%) | PCL-5 | 3–5 months after ICU discharge |

| Asimakopoulou and Madianos [21] | March 2009–June 2011 | Greece | General hospitals | 102 | 45.98 ± 15.17 | 65 (63.7%) | 18 (17.6%) | Mini DSM-IV | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Bashar et al. [22] | 2018 | Iran | Mixed ICU | 181 | 65 | 60 (33%) | 181 (100%) | IES-R | 3–21 days after ICU discharge |

| Bienvenu et al. [6] | October 2004–October 2007 | USA | Mixed ICU | 151 (3 months) | 49 ± 14 | 123 (55%) | 36 (23.8%) | IES-R | 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after ICU admission |

| 161 (6 months) | 32 (19.8%) | ||||||||

| 141 (12 months) | 32 (22.7%) | ||||||||

| 135 (24 months) | 32 (23.7%) | ||||||||

| Boer et al. [23] | December 2001–February 2005 | Netherlands | Surgical ICU | 108 | 66.8 (57–73)* | 41 (38%) | 41 (38%) | PTSS-10 and IES-R | 1 year after ICU admission |

| Bugedo et al. [24] | April 2006–January 2007 | Chile | Not reported | 75 | 59.5 | Not reported | 20 (26.66%) | PTSS-10 | 1 year after ICU admission |

| Castillo et al. [25] | September 2012–February 2013 | Australia | Mixed ICU | 101 (3 months) | 54 ± 15 | 98 (70%) | 19 (18.8%) | PTSS-10 | 3 and 6 months after ICU discharge |

| 92 (6 months) | 15 (16.3%) | ||||||||

| Chahraoui et al. [26] | January–June 2013 | France | Medical ICU | 20 | 68 ± 8.5 | 9 (45%) | 3 (15%) | IES-R | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Cox et al. [27] | 2009–2010 | USA | Mixed ICU | 21 | 56 (47–74)* | 9 (43%) | 12 (57.1%) | PTSS-10 | 6 weeks after hospital discharge |

| Cuthbertson et al. [28] | Not reported | Scotland | Mixed ICU | 78 | 58 (18–87)* | 44 (56%) | 11 (14.1%) | DSM-IV | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Da Costa et al. [29] | September 2008–August 2009 | Brazil | Medical ICU | 138 | 43.5 (17) | 95 (68.8%) | 7 (5%) | IES-R | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Davydow et al. [30] | Not reported | Not reported | Trauma ICU | 1456 | 40.8 (32.0)* | Not reported | 364 (25%) | PCL-17 | 12 months after ICU discharge |

| Davydow et al. [31] | September 2010–August 2011 | USA | Mixed ICU | 131 (3 months) | 49.0 ± 14.6 | 69 (57.5%) | 20 (15.2%) | PCL-C | 3 and 12 months after ICU discharge |

| 120 (12 months) | 18 (15%) | ||||||||

| de Miranda et al. [32] | Not reported | France | Not reported | 126 | 67 (57–75)* | Not reported | 26 (20.6%) | IES-R | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Elliott et al. [33] | Not reported | Australia | Not reported | 178 | 57.20 ± 17.20 | 116 (65%) | 24 (13.5%) | PCL-S | 6 months after hospital discharge |

| Girard et al. [34] | February–May 2001 | USA | Medical and cardiac ICU | 43 | 52 (39–65)* | 20 (47%) | 6 (13.9%) | PTSS-10 | 6 months after hospital discharge |

| Granja et al. [35] | January–June 2015 | Portugal | Not reported | 313 | 59 (44–71)* | 183 (58%) | 54 (17.2%) | PTSS-14 | 6 months after ICU discharge |

| Griffiths et al. [36] | January 2000–December 2002 | England | Not reported | 108 | 56.9 | Not reported | 56 (54.7%) | PTSS-10 | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Günther et al. [37] | December 2015–March 2016 | Sweden | Mixed ICU | 30 | 62 ± 15 | 18 (60%) | 4 (13.3%) | PTSS-10 | 1 week after ICU discharge |

| Hauer et al. [38] | Not reported | Germany | Not reported | 33 | 40.3 ± 12.5 | 16 (48%) | 9 (27.3%) | PTSS-10 | 7.5 ± 2.9 years after ICU discharge |

| Hauer et al. [39] | July 2004–July 2005 | Germany | Cardiac ICU | 126 | 66 ± 9.5 | Not reported | 15 (11.9%) | PTSS-10 | 6 months after ICU admission |

| Hepp et al. [40] | January 1996–June 2000 | Sweden | Trauma ICU | 90 | 38.9 ± 13.2 | 69 (77%) | 32 (36%) | CAPS | Up to 3 years after ICU admission |

| Huang et al. [41] | Not reported | Not reported | Medical ICU | 605 (6 months) | 49 ± 15 | Not reported | 148 (24.5%) | IES-R | 6 and 12 months after ICU admission |

| 573 (12 months) | 132 (23%) | ||||||||

| Jackson et al. [3] | March 2007–June 2010 | USA | Medical or surgical ICU | 467 (3 months) | 59 (49–69)* | 234 (50%) | 27 (5.8%) | PCL-S | 3 and 12 months after hospital discharge |

| 467 (12 months) | 59 (49–69)* | 24 (5.1%) | |||||||

| Jones et al. [42] | 2003–2005 | England | Mixed ICU | 238 | 61 (17–86)* | 149 (62%) | 22 (9.2%) | PTSS-14 | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Jones et al. [43] | 2006–2008 | Europe | Not reported | 332 | 59.9 | 210 (63.2%) | 29 (8.7%) | TSQ | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Jónasdóttir et al. [44] | 2017 | Iceland | Mixed ICU | 143 | Not reported | M—88 (61.5%) |

12/130 (9%) (3 months) |

IES-R | 3, 6, and 12 months after ICU discharge |

|

15/110 (14%) (6 months) | |||||||||

|

15/102 (15%) (12 months) | |||||||||

| Jubran et al. [45] | Not reported | USA | Long-term ICU | 41 | 66 (59–72)* | 26 (63%) | 5 (12.2%) | PTSS-10 | 3 months after weaning |

| Kapfhammer et al. [46] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 46 (discharge) | 36.5 (18.0–50.0)* | Not reported | 20 (43.5%) | DSM-IV | At ICU discharge and (average of) 8 years after ICU discharge |

| Kress et al. [47] | Not reported | USA | Medical ICU | 32 | 48.1 | 20 (62.5) | 6 (18.7) | IES-R | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Myhren et al. [48] | February 2006–December 2006 | Norway | Mixed, medical and cardiac ICU | 238 | 47.9 (15.7) | 160 (62.7) | 64 (26.8) | IES | 4–6 weeks after ICU discharge |

| Myhren et al. [49] | February 2005–December 2006 | Norway | Mixed, medical, and cardiac ICU | 180 | 47.9 (15.7)* | Not reported | 48 (26.6%) | IES | 12 months after ICU discharge |

| Nickel et al. [50] | 1999–2000 | Germany | Medical ICU | 41 | 47.4 | Not reported | 4 (9.7%) | SCID | 3–15 months after ICU discharge (average: 6.2 months) |

| Richter et al. [51] | Not reported | Germany | Surgical ICU | 37 | 41.7 (17.0)* | 28 (76%) | 3 (8.1%) | DSM-IV | Mean of 35 (±14) months after ICU discharge |

| Samuelson et al. [52] | September 2003–March 2005 | Sweden | Medical ICU | 226 | 63.3 (13.4) | 117 (52%) | 19 (8.4%) | IES-R | 12 months after ICU discharge |

| Schellinget al. [53] | Not reported | Germany | Not reported | 54 | 54.2 | Not reported | 21 (38.8%) | PTSS-10 | Not reported |

| Schelling et al. [54] | Not reported | Germany | Not reported | 20 | 51.8 | 8 (40%) | 8 (40%) | DSM-IV | Median 31 months after ICU discharge |

| Schnyder et al. [55] | January 1996–June 1997 | Switzerland | Trauma ICU | 106 | 37.5 (13.2) | Not reported | 5 (4.7%) | DSM-IV | Within 1 month of trauma (median 13.7 days) |

| Scragg et al. [56] | October 1995–October 1997 | England | Medical ICU | 80 | 57.1 | 42 (52.5%) | 12 (15%) | IES | Not reported |

| Shaw et al. [57] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 20 | Not reported | Not reported | 7 (35%) | IES | Not reported |

| Strøm et al. [58] | Not reported | Denmark | Mixed, medical and surgical ICU | 26 | 67.0 | 9 (34.61%) | 1 (3.8%) | PTSS-10 | 2 years after ICU stay |

| Twigg et al. [59] | December 2000–February 2002 | United Kingdom | Medical ICU | 44 | 56.0 | 20 (45.4%) | 10 (22.7%) | PTSS-14 | 3 months after ICU discharge |

| Van der Schaaf et al. [60] | June 2004–June 2005 | Netherlands | Mixed ICU | 255 | 58.8 (16.6) | 166 (69%) | 43 (16.8%) | IES | 1 year after ICU admission |

| Wade et al. [61] | November 2008–September 2009 | England | Medical ICU | 100 | 57.2 (17.4) | 52 (52%) | 27 (27%) | PDS | 3 months after ICU admission |

| Wallen et al. [62] | Not reported | Australia | Mixed, medical, surgical and trauma ICU | 100 | 63 (29.8) | 68 (68%) | 13 (13%) | IES-R | 1 month after ICU discharge |

| Weinert and Sprenkle [63] | 2001–2003 | USA | Mixed, medical and surgical ICU | 80 | 54.6 | Not reported | 12 (15%) | PDS | 6 months after ICU admission |

| Wintermann et al. [64] | 2017 | Germany | Long-term ICU | 97 | Not reported | 73 (75.2%) | 29/97 (29.9%) | PTSS-10 | 3 and 6 months post-transfer (combined result) |

CAPS Clinician-Administered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale; DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; DTS Davidson Trauma Scale; IES Impact of Event Scale; IES-R Impact of Event Scale—revised, PCL-5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian V5; PCL-17 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian V17; PCL-C Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian Version; PCL-S Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Specific Version; PDS Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale; PTSS-10 Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome 10-Question Inventory; PTSS-14 Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome 14-Question Inventory; SCID Structured Clinical Interview; TSQ Trauma Screening Questionnaire

*Median (interquartile range)

Prevalence of PTSD

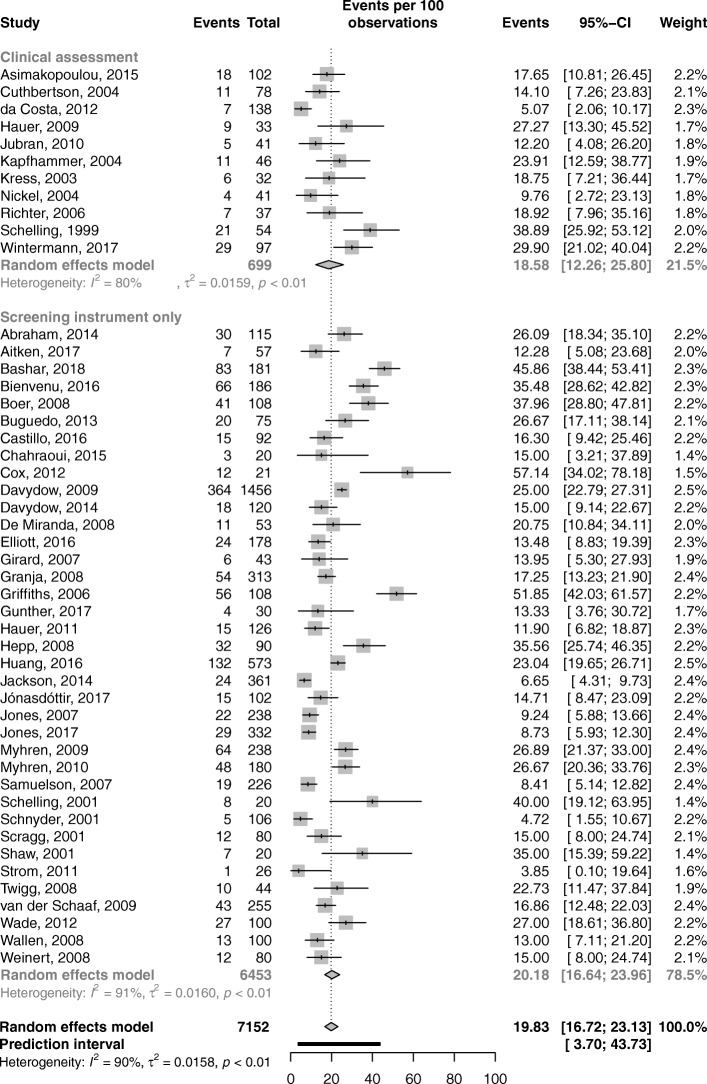

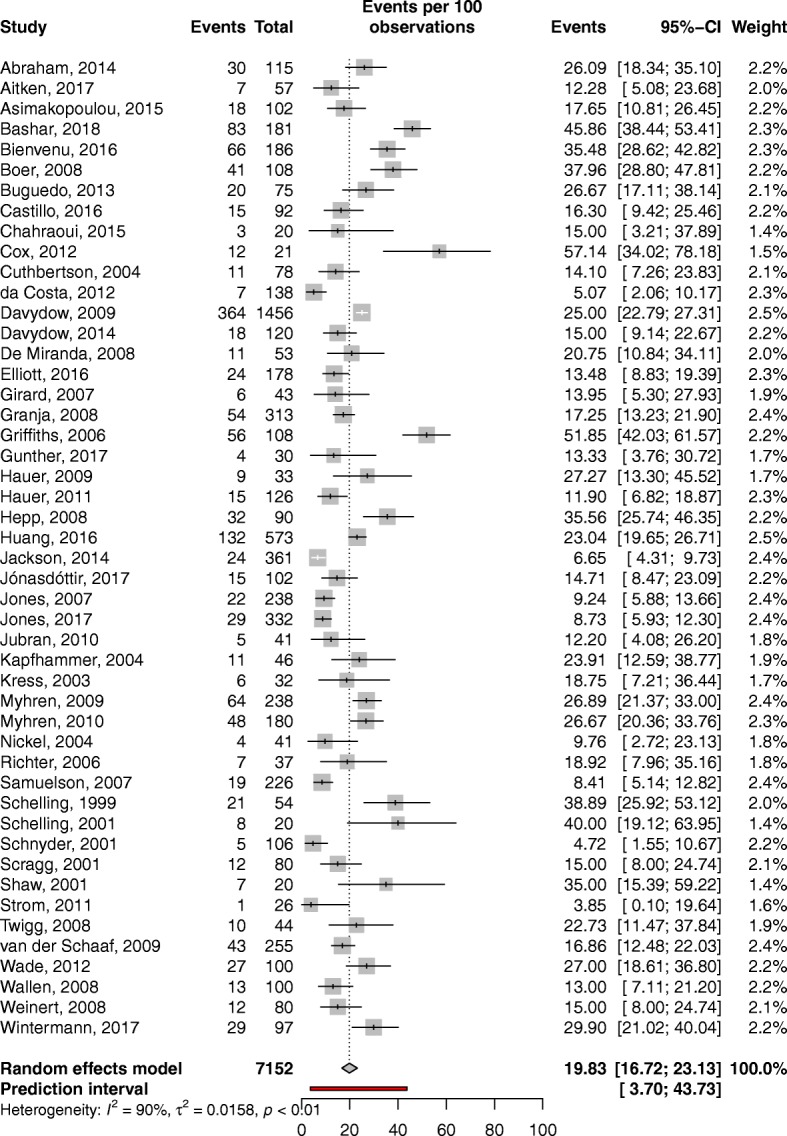

The overall pooled prevalence of PTSD symptoms in ICU survivors was 19.83% (95% CI, 16.72–23.13; I2 = 90%; low quality of evidence) (Fig. 2). The prediction interval for overall PTSD symptoms estimate ranged from 3.70 to 43.73%, with 95% confidence. This prediction interval represents the range of expected PTSD prevalence after ICU discharge in 95% of settings.

Fig. 2.

Overall pooled prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in adult critical care survivors

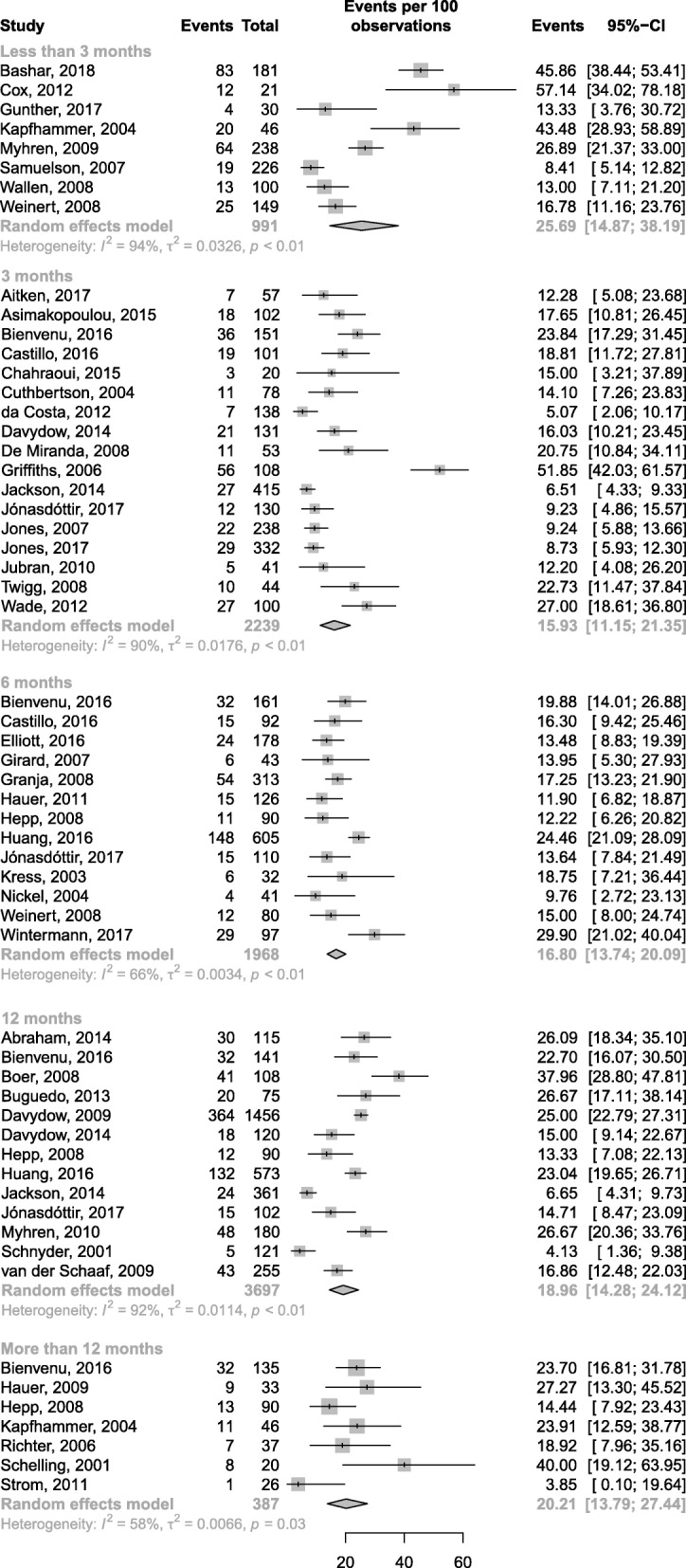

The prevalence of PTSD symptoms ranged from 15.93 to 25.69% according to the time of assessment (Fig. 3). Point prevalence estimates were 15.93% (95% CI, 11.15–21.35.00; I2 = 90%; 17 studies), 16.80% (95% CI, 13.74–20.09; I2 = 66%; 13 studies), 18.96% (95% CI, 14.28–24.12; I2 = 92%; 13 studies), and 20.21% (95% CI, 13.79–27.44; I2 = 58%; 7 studies) at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months after discharge, respectively. Eight studies [22, 27, 37, 46, 49, 52, 62, 63] measured the prevalence of symptoms associated with PTSD up to 3 months after ICU discharge, yielding a pooled prevalence estimate of 25.69% (95% CI, 14.87–38.19; I2 = 94%). However, this high estimate may refer mainly to acute stress disorder rather than PTSD, since in most cases it resolved within 3 months.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder according to the time point of assessment

Subgroup analysis showed that PTSD prevalence as measured by screening instruments alone was 20.18% (95% CI, 16.64–23.96; I2 = 91%). When the diagnosis was based on clinical assessment, PTSD prevalence was 18.58% (95% CI, 12.26–25.80; I2 = 80%) (Fig. 4). The difference between these two subgroups was not statistically significant (p = 0.71). Additional analyses according to different instruments used at different time points provided similar results (Additional file 1: Table S2, Figure S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder according to the assessment method

Meta-regression analysis showed no linear association between the prevalence of PTSD symptoms and mean participant age or percentage of respondents in the study (data not shown).

Quality of evidence

A summary of the risk of bias in the included studies, based on the JBI tool, is provided in Additional file 1: Table S3. No study was rated as having high quality; all had limitations in at least 1 of the 3 prespecified domains (participants, outcome measurement, and statistics). Most studies (n = 45, 94%) clearly described the study participants and the setting. However, most studies (n = 29, 61%) had a study population that did not appropriately address our target population, since they included patients only from specific ICU settings or with specific medical conditions. Twenty-seven studies (56%) did not report how patients were recruited. Eleven studies (23%) had an inadequate response rate. Regarding outcome measurement, most studies (n = 45, 94%) assessed PTSD using a standard method for all patients. However, only 10 studies (21%) used clinical assessment to diagnose PTSD, while the other 38 (79%) used only screening instruments. All studies performed appropriate statistical analyses, but the sample size was considered inappropriate in 19 studies (40%).

The overall quality of evidence for PTSD symptoms prevalence estimates was rated as low according to GRADE, mainly because the studies provided only indirect evidence (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 48 studies, we found that 1 in every 5 adult survivors of critical care (19.83%) develops PTSD symptoms in the year following ICU discharge. The pooled prevalence of PTSD symptoms in critical care survivors was comparable to that of civilian war survivors (26%) [65], but much higher than that reported in many countries among those exposed to traumatic events (2.5–3.5%) [66]. It was also similar to the 20% prevalence of mental disorder after humanitarian emergencies estimated by the World Health Organization [67]. In the USA, 5.7 million patients are admitted annually to ICUs, with an average mortality rate ranging from 10 to 29% [68]. These data allow us to estimate that approximately 1 million patients develop PTSD after ICU admission annually.

In the present study, the pooled prevalence of PTSD symptoms was 25.69% when measured shortly after ICU discharge (less than 3 months). However, such a high early prevalence of PTSD symptoms may reflect acute stress disorder rather than PTSD. Acute stress symptoms are similar to the post-traumatic stress symptoms that occur within the first month of exposure to a stressor, such as ICU admission [4]. Acute stress disorder may be triggered by fragmented ICU memories of traumatic or psychotic experiences [42] and is a risk factor for the development of PTSD [69]. Although lower, the prevalence range (from 15.93% at 3 months to 18.96% at 12 months) is clinically important, since it may have a negative impact on the quality of life in long-term ICU survivors.

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, despite the use of rigorous, up-to-date methods of data analysis and quality of evidence assessment and a comprehensive search of 6 databases that identified more than 13,000 records, only a few studies reporting data on PTSD prevalence in ICU survivors in specific settings were eligible for inclusion. In addition, most of the included studies had methodological issues that limited the generalizability of the results. Second, PTSD was assessed using different strategies in the included studies. As discussed previously, the diagnosis of PTSD can be challenging, and the use of screening instruments may overestimate PTSD prevalence [70]. However, to date, only a few instruments have been validated for use in the ICU, of which only the Impact of Event Scale—revised [71] and the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome 10-Question Inventory have shown good correlation with clinical diagnosis [72]. The lack of proper validation of methods used to evaluate PTSD, as well as their heterogeneity, may have had an impact on the exact prevalence measured in the different studies. However, this impact was minimized in the present systematic review, since similar prevalence estimates of PTSD symptoms were obtained with both clinical assessment (18.58%) and screening instruments (20.18%). Third, there was no parallel assessment of cognitive function in the included studies. An association of long-term PTSD with cognitive dysfunction has been recently reported [73]; however, to date, it remains unknown how cognitive dysfunction can influence PTSD assessment and follow-up, especially regarding consolidation of traumatic memories during mechanical ventilation and sedation. Moreover, PTSD can coexist and be confused with other major psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety [74]. Fourth, the observed statistical heterogeneity was high (90%). However, in contrast with randomized trials, non-controlled studies (e.g., studies of prevalence and incidence) usually have smaller variances and narrower CIs, even with small sample sizes. Thus, a high statistical inconsistency is often expected in meta-analyses of prevalence estimates. Given that the estimates of individual studies included in our meta-analysis ranged mostly from 12 to 30% (similar to the pooled estimate and included in the prediction interval), and we observed consistent results within subgroup analyses (according to instrument used for diagnosis, length of time after ICU stay, and demographic factors), we hypothesize that most of observed inconsistencies may have been the result of the diversity of settings (e.g., patient and ICU characteristics). Fifth, despite the high prevalence observed, it was not possible to establish a direct causal relationship between ICU stay and PTSD, which may be partially explained by other factors, such as the underlying condition of each patient. In this context, action should be taken to further explore the causal relationship between ICU stay and PTSD, as well as to more accurately identify individuals at increased risk of developing PTSD symptoms.

Common stressors in critically ill patients, such as respiratory failure, inflammation, delirium, and communication barriers, may contribute to the occurrence of PTSD, and proper prevention and management of these factors may reduce PTSD incidence after ICU discharge [75]. Also, evidence is emerging that an ICU diary—written by family members or ICU staff—may help patients fill in gaps in their memories, thus reducing the risk of PTSD development [42, 76, 77]. The increased prevalence of PTSD over time in cases that have not received treatment for PTSD symptoms must be highlighted. Although there is little evidence to support the effectiveness of interventions to improve PTSD symptoms among ICU survivors, early treatment with psychotherapy or pharmacological therapy (e.g., antidepressants) may improve quality of life, as observed in PTSD associated with other stressful events [78].

Overall, our findings may have important clinical implications. Despite the high prevalence of PTSD, this disorder is probably underdiagnosed in the post-ICU population. ICU survivors should be screened for PTSD symptoms and cared for accordingly, given the high rates and potential negative impact of PTSD on quality of life. In addition, early and effective measures should be implemented during and after ICU stay to prevent PTSD in this population.

Conclusion

PTSD symptoms affect a large proportion of critical care survivors, with a high expected prevalence in the first year following discharge from the ICU. Screening of ICU patients for PTSD symptoms, followed by proper support and treatment, is needed, given the potential negative impact of PTSD on quality of life. Additional studies should explore whether a causal relationship exists between ICU stay and PTSD, as well as propose additional measures to prevent and treat PTSD among critically ill patients.

Additional file

Table S1. Search strategy. Table S2. Classification of studies according to the instrument used and the time point of assessment. Figure S1. PTSD symptoms assessed with PTSS-10 up to 3 months after an ICU stay. Figure S2. Clinical assessment of PTSD and assessment of PTSD symptoms with IES-R, 3 months after an ICU stay. Figure S3. PTSD symptoms assessed with IES-R and PTSS-10, 6 months after an ICU stay. Figure S4. PTSD symptoms assessed with IES-R and IES, 1 year after an ICU stay. Figure S5. Clinical assessment of PTSD assessed more than 1 year after an ICU stay. Table S3. Risk of bias in included studies (Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist). Table S4. Quality of evidence for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence by the GRADE approach. (DOCX 711 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Hospital Moinhos de Vento and the Brazilian Ministry of Health for their support. We also thank Pedro Emmanuel Alvarenga Americano do Brasil for his assistance in formulating the search strategy.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CoCoPop

Condition, Context, Population

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Authors’ contributions

RGR, CBM, CCR, CT, FAB, and MF developed the original concept of this systematic review and meta-analysis. CR, RTAS, CBM, and FAB contributed to the screening of eligible studies, data extraction, and data synthesis. CR, RGR, FAB, CBM, CCR, and MF drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and take public responsibility for it. FAB and MF contributed equally to this study.

Funding

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health through the Program of Institutional Development of the Brazilian Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS).

Availability of data and materials

All data related to the present systematic review and meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cássia Righy, Email: cassiarighy@gmail.com.

Regis Goulart Rosa, Phone: +55-51-3314.3385, Email: regis.rosa@hmv.org.br.

Rodrigo Teixeira Amancio da Silva, Email: amancio.rt@gmail.com.

Renata Kochhann, Email: renata.kochhann@hmv.org.br.

Celina Borges Migliavaca, Email: celina.migliavaca@hmv.org.br.

Caroline Cabral Robinson, Email: caroline.robinson@hmv.org.br.

Stefania Pigatto Teche, Email: stepigatto@gmail.com.

Cassiano Teixeira, Email: cassiano.rush@gmail.com.

Fernando Augusto Bozza, Email: bozza.fernando@gmail.com.

Maicon Falavigna, Email: maicon.falavigna@hmv.org.br.

References

- 1.Meyer N, Harhay MO, Small DS, Prescott HC, Bowles KH, Gaieski DF, et al. Temporal trends in incidence, sepsis-related mortality, and hospital-based acute care after sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:354–360. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lilly CM, Swami S, Liu X, Riker RR, Badawi O. Five-year trends of critical care practice and outcomes. Chest. 2017;152:723–735. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javidi H, Yadollahie M. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2012;3:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Pronovost PJ, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642–653. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joanna Briggs Institute . Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2014 edition. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1506–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Dasai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, Alba C, Lang E, Burnand B, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarzer G. meta: an R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham CM, Obremskey WT, Song Y, Jackson JC, Ely EW, Archer KR. Hospital delirium and psychological distress at 1 year and health-related quality of life after moderate-to-severe traumatic injury without intracranial hemorrhage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(12):2382–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aitken LM, Rattray J, Kenardy J, Hull AM, Ullman AJ, Le Brocque R, et al. Perspectives of patients and family members regarding psychological support using intensive care diaries: an exploratory mixed methods study. J Crit Care. 2017;38:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asimakopoulou E, Madianos M. Posttraumatic stress disorder after discharge from intensive care units in greater Athens area. J Trauma Nurs. 2015;22(4):209–217. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bashar FR, Vahedian-Azimi A, Hajiesmaeili M, Salesi M, Farzanegan B, Shojaei S, et al. Post-ICU psychological morbidity in very long ICU stay patients with ARDS and delirium. J Crit Care. 2018;43:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boer KR, van Ruler O, van Emmerik AA, Sprangers MA, de Rooij SE, Vroom MB, et al; Dutch Peritonitis Study Group. Factors associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms in a prospective cohort of patients after abdominal sepsis: a nomogram. Intensive Care Med 2008;34(4):664–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bugedo G, Tobar E, Aguirre M, Gonzalez H, Godoy J, Lira MT. The implementation of an analgesia-based sedation protocol reduced deep sedation and proved to be safe and feasible in patients on mechanical ventilation. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2013;25(3):188–196. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20130034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castillo MI, Cooke ML, Macfarlane B, Aitken LM. In ICU state anxiety is not associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms over six months after ICU discharge: a prospective study. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chahraoui K, Laurent A, Bioy A, Quenot JP. Psychological experience of patients 3 months after a stay in the intensive care unit: a descriptive and qualitative study. J Crit Care. 2015;30(3):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox CE, Porter LS, Hough CL, White DB, Kahn JM, Carson SS, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based coping skills training intervention for survivors of acute lung injury and their informal caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuthbertson BH, Hull A, Strachan M, Scott J. Post-traumatic stress disorder after critical illness requiring general intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):450–455. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Costa JB, Marcon SS, Rossi RM. Transtorno de estresse pós-traumático e a presença de recordações referentes à unidade de terapia intensiva. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;61:13–19. doi: 10.1590/S0047-20852012000100004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davydow DS, Zatzick DF, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Wang J, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and return to usual major activity in traumatically injured intensive care unit survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davydow DS, Zatzick D, Hough CL, Katon WJ. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms over the course of the year following medical-surgical intensive care unit admission. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Miranda S, Pochard F, Chaize M, Megarbane B, Cuvelier A, Bele N, et al. Postintensive care unit psychological burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and informal caregivers: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):112–118. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feb824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott R, McKinley S, Fien M, Elliott D. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in intensive care patients: an exploration of associated factors. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:141–150. doi: 10.1037/rep0000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girard TD, Shintani AK, Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Pun BT, Henderson MS, et al. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms following critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R28. doi: 10.1186/cc5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Granja C, Gomes E, Amaro A, Ribeiro O, Jones C, Carneiro A, et al. Understanding posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after critical care: the early illness amnesia hypothesis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2801–2809. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a3e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths J, Gager M, Alder N, Fawcett D, Waldmann C, Quinlan J. A self-report-based study of the incidence and associations of sexual dysfunction in survivors of intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(3):445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-0048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Günther A, Sackey P, Bjärtå A, Schandl A. The relation between skin conductance responses and recovery from symptoms of PTSD. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61:688–695. doi: 10.1111/aas.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauer D, Weis F, Krauseneck T, Vogeser M, Schelling G, Roozendaal B. Traumatic memories, post-traumatic stress disorder and serum cortisol levels in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Brain Res. 2009;1293:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauer D, Weis F, Papassotiropoulos A, Schmoeckel M, Beiras-Fernandez A, Lieke J, et al. Relationship of a common polymorphism of the glucocorticoid receptor gene to traumatic memories and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after intensive care therapy. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):643–650. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206bae6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hepp U, Moergeli H, Buchi S, Bruchhaus-Steinert H, Kraemer B, Sensky T, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in serious accidental injury: 3-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):376–383. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, Dinglas VD, Colantuoni E, Hopkins RO, et al; National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute acute respiratory distress syndrome network. Psychiatric symptoms in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors: a 1-year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med 2016;44(5):954–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, et al. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R168. doi: 10.1186/cc9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones JM, Williams WH, Jetten J, Haslam SA, Harris A, Gleibs IH. The role of psychological symptoms and social group memberships in the development of post-traumatic stress after traumatic injury. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(4):798–811. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jónasdóttir RJ, Jónsdóttir H, Gudmundsdottir B, Sigurdsson GH. Psychological recovery after intensive care: outcomes of a long-term quasi-experimental study of structured nurse-led follow-up. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;44:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jubran A, Lawm G, Duffner LA, Collins EG, Lanuza DM, Hoffman LA, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder after weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(12):2030–2037. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1972-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhäusler HB, Krauseneck T, Stoll C, Schelling G. Posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:45–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kress JP, Gehlbach B, Lacy M, Pliskin N, Pohlman AS, Hall JB. The long-term psychological effects of daily sedative interruption on critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(12):1457–1461. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-455OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myhren H, Tøien K, Ekeberg O, Karlsson S, Sandvik L, Stokland O. Patients’ memory and psychological distress after ICU stay compared with expectations of the relatives. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2078–2086. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Tøien K, Karlsson S, Stokland O. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression symptoms in patients during the first year post intensive care unit discharge. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R14. doi: 10.1186/cc8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nickel M, Leiberich P, Nickel C, Tritt K, Mitterlehner F, Rother W, et al. The occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients following intensive care treatment: a cross-sectional study in a random sample. J Intensive Care Med. 2004;19(5):285–290. doi: 10.1177/0885066604267684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richter JC, Waydhas C, Pajonk FG. Incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder after prolonged surgical intensive care unit treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):223–230. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samuelson KA, Lundberg D, Fridlund B. Stressful memories and psychological distress in adult mechanically ventilated intensive care patients - a 2-month follow-up study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(6):671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schelling G, Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhäusler HB, Krauseneck T, Durst K, et al. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in survivors. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(12):2678–2683. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schelling G, Briegel J, Roozendaal B, Stoll C, Rothenhäusler HB, Kapfhammer HP. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(12):978–985. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C. Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):594–599. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scragg P, Jones A, Fauvel N. Psychological problems following ICU treatment. Anaesthesia. 2001;56(1):9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaw RJ, Harvey JE, Nelson KL, Gunary R, Kruk H, Steiner H. Linguistic analysis to assess medically related posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(1):35–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strøm T, Stylsvig M, Toft P. Long-term psychological effects of a no-sedation protocol in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R293. doi: 10.1186/cc10586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Twigg E, Humphris G, Jones C, Bramwell R, Griffiths RD. Use of a screening questionnaire for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a sample of UK ICU patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, Vroom MB, Nollet F. Functional status after intensive care: a challenge for rehabilitation professionals to improve outcome. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(5):360–366. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wade DM, Howell DC, Weinman JA, Hardy RJ, Mythen MG, Brewin CR, et al. Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):R192. doi: 10.1186/cc11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallen K, Chaboyer W, Thalib L, Creedy DK. Symptoms of acute posttraumatic stress disorder after intensive care. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(6):534–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weinert CR, Sprenkle M. Post-ICU consequences of patient wakefulness and sedative exposure during mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(1):82–90. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wintermann GB, Rosendahl J, Weidner K, Strauß B, Petrowski K. Risk factors of delayed onset posttraumatic stress disorder in chronically critically ill patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(10):780–787. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morina N, Stam K, Pollet TV, Priebe S. Prevalence of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in adult civilian survivors of war who stay in war-afflicted regions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, McLaughlin KA. Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: prevalence, correlates and consequences. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:307–311. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Ommeren M, Saxena S, Saraceno B. Aid after disasters. BMJ. 2005;330:1160–1161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7501.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Society of Critical Care Medicine. Critical Care Statistics. https://sccm.org/Communications/Critical-Care-Statistics. Accessed 5 Aug 2015.

- 69.Roberts MB, Glaspey LJ, Mazzarelli A, Jones CW, Kilgannon HJ, Trzeciak S, et al. Early interventions for the prevention of posttraumatic stress symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a qualitative systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2018;4:1328–1333. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGiffin JN, Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Is the intensive care unit traumatic? What we know and don’t know about the intensive care unit and posttraumatic stress responses. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:120–131. doi: 10.1037/rep0000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bienvenu OJ, Williams JB, Yang A, Hopkins RO, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury: evaluating the impact of event scale-revised. Chest. 2013;144:24–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhäusler HB, Haller M, Briegel J, Schmidt M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a screening test to document traumatic experiences and to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder in ARDS patients after intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(7):697–704. doi: 10.1007/s001340050932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brück E, Schandl A, Bottai M, Sackey P. The impact of sepsis, delirium, and psychological distress on self-rated cognitive function in ICU survivors-a prospective cohort study. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:2. doi: 10.1186/s40560-017-0272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Engelhard IM, Arntz A, van den Hout MA. Low specificity of symptoms on the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom scale: a comparison of individuals with PTSD, individuals with other anxiety disorders and individuals without psychopathology. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46(Pt 4):449–456. doi: 10.1348/014466507X206883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bienvenu OJ, Gerstenblith TA. Posttraumatic stress disorder phenomena after critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33:649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Coquet I, Périer A, Timsit JF, Pochard F, Lancrin F, et al. Impact of an intensive care unit diary on psychological distress in patients and relatives. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2033–2040. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e1b43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Flahault C, Fasse L, et al. The ICU-diary study: prospective, multicenter comparative study of the impact of an ICU diary on the wellbeing of patients and families in French ICUs. Trials. 2017;18(1):542. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steckler T, Risbrough V. Pharmacological treatment of PTSD - established and new approaches. Neuropharmacology. 2011;62(2):617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search strategy. Table S2. Classification of studies according to the instrument used and the time point of assessment. Figure S1. PTSD symptoms assessed with PTSS-10 up to 3 months after an ICU stay. Figure S2. Clinical assessment of PTSD and assessment of PTSD symptoms with IES-R, 3 months after an ICU stay. Figure S3. PTSD symptoms assessed with IES-R and PTSS-10, 6 months after an ICU stay. Figure S4. PTSD symptoms assessed with IES-R and IES, 1 year after an ICU stay. Figure S5. Clinical assessment of PTSD assessed more than 1 year after an ICU stay. Table S3. Risk of bias in included studies (Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist). Table S4. Quality of evidence for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence by the GRADE approach. (DOCX 711 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data related to the present systematic review and meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.