Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the accuracy and quality of immunization data on the pentavalent (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib)) and MMR vaccines as the administrative data of the expanded program on immunization (EPI) in Iran.

Methods

We conducted a Data Quality Self-assessment (DQS) survey from October to December 2017. Standardized DQS tools were used to assess the accuracy of reported immunizations data and quality of the immunization monitoring system at the provincial level of the healthcare system including health houses, health posts, rural and urban health centers and district health centers. Multistage cluster random sampling with proportional to size (PPS) weights was used to select target provinces and related health units. Accuracy ratio, quality index (QI), completeness and relevant quality indices of first dose of MMR (MMR1) and third dose of pentavalent vaccines were reported. Corresponding period of the survey was limited to reported administrative immunization data during the first 6 months of 2016.

Results

In relation to accuracy ratio, there was some evidence of under reporting of pentavalent (3rd dose) and MMR1 vaccines in health house units which were 100.94 and 101.1%, respectively. Completeness of reporting for both vaccines at different provincial levels was near 100%. However, the corresponding value for pentavalent (3rd dose) and MMR1 vaccines at the level of urban health centers was 96.67 and 94.17% respectively.

Among the five components of a monitoring system data usage and core output had the lowest QI scores in either rural or urban as well as district healthcare centers.

Conclusions

Findings from our DQS survey reveals that administrative reporting of the immunization data was adequate at provincial and district levels of the healthcare centers. Although, addressing the existing concerns regarding timelines of the reporting by health authorities and staffs of EPI is warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12913-019-4188-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Immunization, Health surveys, Data quality self-assessment, Quality control, Data accuracy, Iran

Background

Immunization controls communicable diseases and is an essential component of public health policies. The vaccination program, as the most cost-effective health intervention eradicates the smallpox and other infectious diseases worldwide [1].

According to the expanded program of immunization (EPI) in Iran, children were vaccinated against ten diseases including bacillus calmette-guerin (BCG), oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), hepatitis B (HBV), diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP), hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type B (pentavalent) and measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) (Appendix 1). The vaccination schedule of EPI was attached in Appendix 1. Immunization services in Iran have been involved into the routine activities of the Primary Health Care (PHC) [2].

Checking the accuracy of data is important for the objectives of surveillance systems. The quality of reports depends upon the quality of primary data. Controlling data quality can also help improve the analysis of health report. The quality of surveillance data can potentially be affected by the degree of clarity of surveillance sheets, the quality of training and persons responsible for completion of the sheets [3]. Little studies about the accuracy of immunization and health system reports have been conducted in Iran despite the advancements in immunization programs. Vaccination program is prerequisite for monitoring vaccine effects, however just a few aspects were examined in this program [4, 5]. The qualitative aspects of immunization were disregarded. Despite the necessity of completeness and timeliness of the reports of immunization quality, these two major components are generally disregarded [6].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently introduced two major tools including DQA and DQS to evaluate the immunization data [7]. In 2003, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) released a tool called Data Quality Audit (DQA) to test the quality, accuracy, completeness and timeliness of immunization data. Ensuring the allocation of resources in line with the objectives of this union is another goal of this tool [5]. A study on 41 low-income countries showed that less than 80% of reports were accurate in half of those countries during 2002–2005 [6].

Data Quality Self-Assessment (DQS) is another tool published by WHO in 2005 [8]. The DQS is a flexible tool to evaluate the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the immunization monitoring system in different levels of healthcare system In fact, it helps countries identify weaknesses and strengths of the immunization program at different levels, and ultimately lead to improving the program and immunization services.

National Immunization Program has been one of the most successful health interventions in Iran [9]; however, 95% of vaccination coverage could not stop the scattered outbreak of measles in the country [10, 11]. With regard to the acceptable indices of immunization coverage in the Islamic Republic of Iran, ensuring the accuracy of the administrative reports on immunization at different levels of the healthcare system seems prudent. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of the immunization reports as well as the quality of the immunization monitoring system (for children under 1 year old) at different healthcare levels during the first 6 months of 2016. Given the convenience of access to demographic information on the denominator for children less than 1 year of age and considering the requirements for the calculation of immunization indices, we decided to investigate the accuracy and quality of immunization data on 3rd dose of pentavalent vaccine and 1st dose of MMR vaccines in Iran.

Methods

The standard methodology of DQS was proposed by WHO [5]. This study assessed the immunization data include administrative reporting of the third dose of pentavalent (pentavalent3) vaccine (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib)) (at the age of 6 months) and first dose of MMR (MMR1) vaccine (at the age of 12 months) among 900 children in the first 6 month (January–June) of 2016.

Study setting

According to the sampling method, we investigated two district health centers throughout five provinces include Ilam, Khorasan Razavi, Hormozgan, Tehran and Yazd. The geographical location of the included provinces has been shown in Fig. 1. As well distribution of study populations according to 2016 census are presented in Appendix 2.

Fig. 1.

Geographical location of studied provinces in DQS survey. (Source: This map has been depicted by authors using Arc Vie Map software)

WHO DQS tool

The DQS is a flexible toolbox of methods to evaluate different aspects of the immunization monitoring system at different health unit levels. By this toolbox data accuracy at different levels and some quality issues like availability of vaccination cards, use of tally sheets, directly-observed recording and reporting practices are assessed through a self-designed questionnaire (Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). By identification of strengths and weaknesses, practical recommendations are made with the aim to improve the use of accurate, timely and complete data for action at all levels. Financial support from GAVI has contributed to the design and testing of the DQS [8].

Sampling scheme for healthcare units (HUs)

We used multistage cluster random sampling with a proportional to size (PPS) weights for selecting HUs. A sequential procedure is described below:

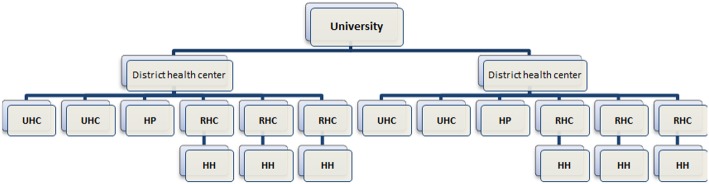

Each of the medical universities proportional to the population of children under 1 year was weighted. So the university with higher frequency of children under 1 year had several times chance to choose. Ultimately five medical universities were selected randomly.

Two district health centers were selected randomly for each medical university (primary sampling unit)

Three rural health centers, two urban health centers (UHC) and one health post (HP) were selected randomly of the covered rural and urban health centers for each district health center (secondary sampling unit)

For each rural health center (RHC) one health house was selected randomly (Tertiary sampling unit)

In total per all included medical universities in the study, 30 health house, 20 urban health centers, 10 health posts, 30 rural health centers and 10 district health centers were choose (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

List of investigated health units covered by each university at provincial level. Abbreviations for Fig. 2: HH: Health house, UHC: urban health centers, RHC: rural health center, HP: health post

Sampling methods to assess the accuracy of recording

Registration folders for immunization of target groups in vaccine inoculation units (health houses, health posts and vaccination ward of urban health centers) were considered as the sampling frame. Names of 12 to 23 months old children were assigned one number from one forward. In continue through systematic random sampling 15 children were selected from each health unit.

Outcome measures definition

The standard formulas for calculation of accuracy ratio, completeness and timeliness were adapted from DQS methods as follow.

Accuracy ratio = Number of vaccinations verified or re-counted from a source at one level/ compared to the number of vaccinations reported by that level to more central levels. Completeness = (Number of reports received / number of reports expected during a period of time) × 100. Timeliness = (Number of reports that were received on time (by the deadline set by the EPI office) / number of reports expected during a period of time) × 100.

Accuracy of reported immunizations data

For assessment of the accuracy of reporting, according to the guidelines [8], the date of vaccination must be recorded on both children’s vaccination card and the immunization logbook provided to health house, health post, and vaccination ward of urban health centers. Moreover, the administered dose should be recorded on an appropriate sheet allowing for the easy re-counting of all doses provided. These Health units’ monthly reports inculcated vaccines to the upper level (rural or urban health center). In order to the assessment of the accuracy of reporting accuracy in this level, the number of administered doses from the tally sheets for each month was compared with the monthly report to the higher level. For rural/urban and district health centers cumulative monthly reports of lower levels were compiled to the monthly report to higher levels.

For assessment of the accuracy of reporting in the community, following selection of 15 children (the required sample size), the interviewers paid them a home visit and the dates of MMR1 and Pentavalent3 vaccines inoculation were recorded based on the vaccine card.

Immunization records in the healthcare unit were then checked to detect any discrepancy between the information registered in the child’s vaccination card and the immunization logbook. Finally accuracy ratio was calculated based on the number of vaccinations verified or re-counted from a source at one level to the number of vaccinations reported by that level to more central levels.

Completeness of HU reporting was calculated for the first 6 months (January–June) of 2016 based on the numbers of HU reports available at the upper level for a given period were re-counted. This is referred to as an indicator of the availability of reports, defined as the proportion of reports physically available at the time of the assessment for a this time period divided by the total number of reports expected to be available.

The timeliness of HU reporting, the dates of sending reports to the upper level were looked. According to the national policy, this date can be + 3 days for health houses, + 5 days for rural and urban health centers and + 12 days for district health centers. Therefore, by calculating the reports that were sent on the defined time interval, the timeline rate of reports were assessed at each level.

Quality of the immunization monitoring system

For assessment of the quality of the immunization monitoring system at different levels, the standardized WHO questionnaire was used. We have used hard copy questionnaires and asked trained assessors to complete the questionnaires. These questions/observations/tasks were grouped into six components of the monitoring system including: Recording, Archiving, Reporting, Demographic information, Core output / analyses and Evidence of using data for action. Questions were modified for each healthcare unit level. For each question, a score was considered. A “no” scores 0, a “yes” scores from 1 to 3 according to its importance, and an “NA” was not recorded in the denominator.

Scores were calculated for each of the identified components, with the number of points corresponding to correct answers as the numerator and the number of possible scores as the denominator. The quality index (QI) was calculated by the following formula:

QI = scores for all questions answered “yes” / sum of maximum scores that could be obtained.

Frequency tables and chart were used for presenting the data. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010 software.

Results

Findings on accuracy ratio

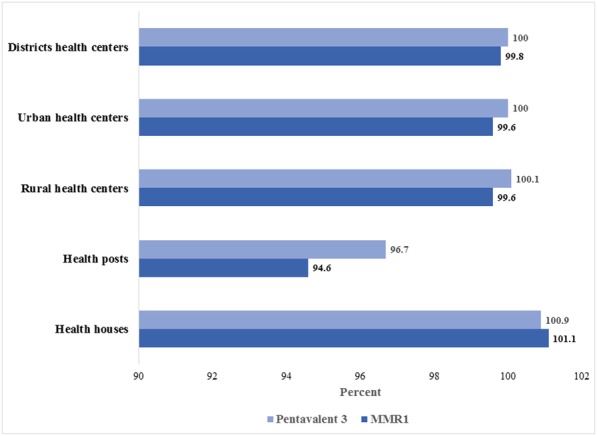

As shown in Fig. 3, there was some evidence of under reporting for pentavalent (3rd dose) in health house units (100.94%) and rural health center units (100.1%); while over- reporting was observed in health post units (96.7%). The accuracy ratio for both urban and district health centers was 100%.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of re-counted third dose of pentavalent and first dose of MMR immunizations which reported by administrative health levels to their higher level in first 6 months of 2016

Apart from health house units with under- reporting, there was some degree of over- reporting for MMR1such a way that the accuracy ratio for rural health centers, urban health centers, health posts and district health centers were 99.6, 99.64, 94.68 and 99.87%, respectively.

Findings on accuracy in the community

A total of 450 children were assessed for accuracy ratio of Pentavalent3 and MMR1. Comparison of child’s vaccination card with immunization registry for pentavalent (3rd dose) and MMR1 revealed an accuracy ratio of 96.55 and 94.35% for health house units; and 93.62 and 92.11% for urban centers, respectively.

Completeness and timeliness of the reporting

As shown in Table 1, completeness of the reporting of the 3rd dose of pentavalent were 100% for health post, rural health center and district health center units, while it was 99.45% for health houses and 96.67% for urban health centers. On the other hand, completeness of MMR1reporting was 98.89% for rural health centers, 94.17% for urban health centers, and 100%for other health units. The lowest percentage of timely reporting belonged to district health centers (83.33%), urban health centers (84.17%), and rural health centers (85%) for pentavalent (3rd dose); and to district health center (83.33%) for MMR1.

Table 1.

Completeness and timeliness of pentavalent (3rd dose) and MMR1 vaccine reporting in different administrative health units

| Health unit | Completeness of reporting (%) | Timeliness of reporting (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pentavalent (3rd dose) | MMR1 | pentavalent (3rd dose) | MMR1 | |

| Health house | 99.4 | 100 | 94.4 | 94.4 |

| Health post | 100 | 100 | 93.3 | 93.3 |

| Rural health center | 100 | 98.8 | 85 | 85.5 |

| Urban health center | 96.6 | 94.1 | 84.1 | 84.1 |

| District health center | 100 | 100 | 83.3 | 83.3 |

Pentavalent: diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); MMR1: Measles-Mumps-Rubella

Findings on quality of the monitoring system

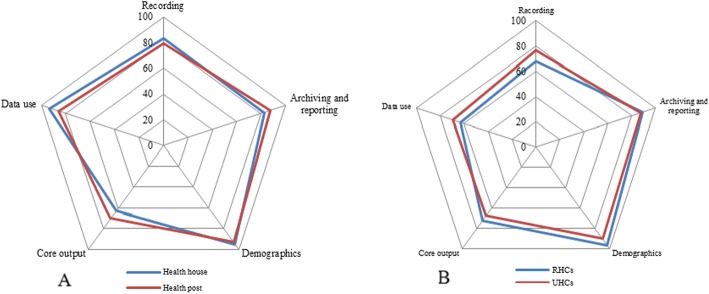

As shown in Table 2 & Fig. 4a, Quality index scores varied in different components of the monitoring system. QI was ranged from 62.7% for core output to 94.7% for demographics at health house levels and ranged from 70% for core output to 92.9% for demographics at health posts levels.

Table 2.

Quality indices (QI) for five components of a monitoring system at house/posts level

| Health unit | Recording | Archiving and reporting | Demographics | Core output | Data use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health house level | Maximum score | 450 | 450 | 438 | 432 | 480 |

| Acquired score | 376 | 370.5 | 415 | 271 | 447 | |

| QI | 83.6 | 82.3 | 94.7 | 62.7 | 93.1 | |

| Health post level | Maximum score | 150 | 150 | 141 | 150 | 180 |

| Acquired score | 119 | 131 | 131 | 105 | 180 | |

| QI | 79.3 | 87.3 | 92.9 | 70 | 86.1 | |

| Total | Maximum score | 600 | 600 | 579 | 582 | 660 |

| Acquired score | 495 | 501.5 | 546 | 376 | 602 | |

| QI | 82.5 | 83.6 | 94.3 | 64.6 | 91.2 | |

Fig. 4.

Quality indices for five components of a monitoring system at health house/posts (a) and health centers (b) level

Qualities of the monitoring system at rural/urban health centers as the second level of vaccination service are presented in Table 3 & Fig. 4b. For RHCs level, QI was ranged from 63.1% for data use to 96.3% for demographics. In this level QI for recording and core output was 68.3 and 72.5% which was not suitable. QI for UHCs level was ranged from 63.4% for data use to 90% for demographics. Totally in this level of vaccination service, core output and recording components with the QI of 65.6, 70.6 and 71.5% had the lowest score, respectively.

Table 3.

Quality indices (QI) for five components of a monitoring system at health centers level

| Health unit | Recording | Archiving and reporting | Demographics | Core output | Data use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHCs level | Maximum score | 246 | 795 | 270 | 360 | 360 |

| Acquired score | 168 | 709 | 260 | 261 | 227 | |

| QI | 68.3 | 89.2 | 96.3 | 72.5 | 63.1 | |

| UHCs level | Maximum score | 150 | 525 | 180 | 231 | 420 |

| Acquired score | 115 | 462 | 162 | 156 | 166.5 | |

| QI | 76.7 | 88 | 90 | 67.5 | 63.4 | |

| Total | Maximum score | 396 | 1320 | 450 | 591 | 600 |

| Acquired score | 283 | 1171 | 420 | 417 | 393.5 | |

| QI | 71.5 | 88.7 | 93.8 | 70.6 | 65.6 | |

Quality indices at district health centers level for recording, archiving and reporting, demographics, core output and data use were 88.33, 95.24, 94.16, 77 and 85%, respectively.

Discussion

Improving the quality of the reported data in immunization program is essential [12]. Thus, WHO has recently introduced DQS tool to examine the immunization coverage for countries. In this study, DQS method was used to evaluate the accuracy of immunization reports as well as the quality of the immunization monitoring system for children less than 1 year old at different healthcare levels in Iran.

Based on the results, quality index scored from 62.7 to 94.7% for core output and demographics at health house levels, respectively. The corresponding values ranged from 70 to 92.9% for demographics at health posts levels. Moreover, there is a negligible proportion of under/ over reporting for pentvalent 3 and MMR1 in different administrative healthcare levels. The accuracy ratios of the two vaccines were about 95 and 93% for health house and health post levels, respectively. The percentage of completeness for vaccine reports were 100% (at all levels), 95% (urban health level) Also, the percentage of timeliness for reporting the administrative health units (health houses and health units) and other levels were nearly 95 and 85%, respectively. The lowest score of quality index belonged to core output in health house and health post units. The lowest QI scores belonged to rural and urban health centers as well as district health centers.

Although the results confirmed the adequacy of accurate information obtained from national immunization registration system, this survey identified major challenges in the national immunization monitoring system in terms of timelines of reporting and quality for core output and data use.

The results of studies aiming at measuring the accuracy and quality of immunization information systems on 41 low-income countries (30 African, 10 Asian and one Caribbean) showed that almost half of the countries obtained a low verification factor (VF) (80%) and nine countries had high VF and quality scores (QS). The most common weaknesses in the information systems of these countries were inconsistency of denominators used to estimate coverage, unavailability of guidelines, incorrect estimations of vaccine wastage and lack of feedback on immunization performance [6, 13]. Adamki et al. conducted a study in eight reproductive and child health units and health centers in Ghana to determine the accuracy and completeness of reported number of vaccinations. They found that the quality of data was generally poor [14]. In another study in Tunisia, the regional verification factor and quality index were estimated to be 85 and 55%, respectively [15]. According to the national data (DQS study) in Uganda in 2013, the quality of administrative vaccination data was not optimal, especially at the subnational level. Inaccurate data on administered doses of vaccine result from lack of knowledge of healthcare staff, standard tools for recording and reporting, and inadequate implementation of recommended practices for data collection, analysis, and use [16]. Inappropriate storage of reports and documents related to the immunization and subsequently data loss was the cause inaccuracy of Cameroon DQA [15].

Monitoring vaccination coverage is one of the most important components of any immunization program [17]. In the present study, there was a small percentage of under/over reporting, which could be affected by reported vaccination coverage by administrative health levels. The inconsistencies of data reporting is not a new issue [18, 19]. Lack of adequate supervision, feedbacks from higher levels, and inadequate incentives of healthcare staff were the main reasons of errors [18, 19].

Pressure from higher levels, inclusion of vaccination conducted outside of target group, reporting doses instead of immunizations, using non- standard tools to report daily vaccinations, miscalculation and loss of verifiable information are attributable to accuracy ratios less than 100%, and in addition to these factors, incomplete reports at the time of forwarding were considered as possible reasons for accuracy ratio higher than 100% [8]. Mostly, the concern relies on over reporting as it could potentially lead to under-vaccination. Thus, using smart software to record vaccination data, supervising the vaccinators’ performance, additional training can improve reporting quality. However, identifying the defects of field and providing the precise, efficient and useful immunization monitoring system is highly recommended.

Quality of the monitoring system was the other aspects of the immunization monitoring system assessed in the present study. The results of this study report the robust capacities and demographics; however, the system did poor in the areas of core outputs/analysis and data use. In fact, raising the capacity of the healthcare workers to manage, analyze, and use the vaccination data is the central component of DQS tool.

Insufficient motivation and inadequate training of healthcare staffs, inappropriate prioritization of activities due to integration of services; inadequate supervision by higher levels and limited financial resources can be considered as the common challenges of the low scores of core output and data use throughout all administrative healthcare levels [16]. The integration of multiple programs in the health system of the country and the change of priorities can be considered as the most important challenges in the quality of immunization quality in the present study.

It should be kept in mind that data quality and data use have a mutual connection, so as they can help drive, demand and use, and consequently motivate to create high quality data. If data are not used to monitor performance changes in target population, or damage stricken areas could not be identified [20].

In this study, we used the DQS tool for comprehensive assessment of immunization data quality in Iran. The output of this tool allowed the assessors to prove the system’s effectiveness by validating the data collected in different administrative healthcare levels.

Financial problems, sample size and a limited amount of archived data were the limitations of this study. Extending the duration of study and examining two different vaccines (pentvalent3 and MMR1) for each child could solve some limitations.

Despite some quantitative and qualitative weaknesses and strengths of the national immunization system, further study should be conducted to determine factors affecting poor quality in core output and data use. Doing DQS survey in other provinces with large samples can lead to more conclusive results.

Conclusions

The output of DQS tool showed that information relating to accuracy ratio from national immunization registration system was adequate; however, there were some weaknesses in timelines of reporting and quality of core output and data use. Integration of DQS concept into the national training schedule, using appropriate software to record vaccination data, supervising the vaccinators’ performance, staff training can improve monitoring practices and management of immunization.

Additional files

Accuracy ratio of pentvalent 3 & MMR1 register in the community (PDF 52 kb)

Accuracy ratio of pentvalent 3 and MMR1vaccines (PDF 9 kb)

Standard questions to assess the quality of the monitoring system (PDF 139 kb)

Standard questions to assess the quality of the monitoring system (PDF 200 kb)

Timeliness and completeness of Pentavalent 3 and MMR1vaccines reporting (PDF 12 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all contributors to this project. Special thanks for all contributors of the project at district and provincial levels who make this project possible.

Abbreviations

- DQA

Data Quality Audit

- DQS

Data Quality Self-assessment

- GAVI

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

- HU

Health unit

- PPS

Proportional to size

- QI

Quality index

- VF

Verification factor

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix

Table 4.

The vaccination schedule of EPI in Iran

| Age | Vaccine |

|---|---|

| At birth | BCG, HBV, OPV |

| 2nd month | OPV, pentavalent |

| 4th month | OPV, pentavalent |

| 6th month | OPV, pentavalent |

| One year old | MMR |

| 18th month | MMR, DTP, OPV |

| 6 years old | DTP, OPV |

BCG Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, HBV Hepatitis B, OPV Oral Poliovirus Vaccine, DTP Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis, Pentavalent: Hepatitis B, Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type b, and MMR Measles-Mumps-Rubella

Table 5.

Distribution of study populations (According to 2016 census)

| Province | Population (2016 census) | under one year of age population (2016 census) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Urban | Rural | Total | Urban | Rural | Total | |

| Ilam | 295,199 | 284,959 | 395,263 | 184,444 | 580,158 | 6570 | 3110 | 9689 |

| Tehran | 667,362 | 6,593,965 | 12,452,230 | 814,698 | 13,267,637 | 177,577 | 6970 | 191,171 |

| Yazd | 586,013 | 552,520 | 971,355 | 166,724 | 1,138,533 | 20,511 | 3189 | 23,700 |

| Khoasan Razavi | 3,245,185 | 3189,316 | 4,700,924 | 1,73,121 | 6,434,501 | 93,270 | 40,702 | 133,978 |

| Hormozgan | 906,814 | 869,601 | 971,822 | 802,512 | 1,776,415 | 22,110 | 19,733 | 41,917 |

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the research. SK, MK, AB, FAY collected the data. SMZ, SK and MK conducted analysis and interpretation of data. All authors drafted the first version. MK, SK, MMG and SMZ edited the first draft. All authors reviewed, commented and approved the final draft.

Funding

This project has been financially support for data gathering by World Health Organization (CONSULTANT CONTRACT NO: 201844593). Funding bodies of this study did not play any role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received the ethical approval from the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences IR.UMSHA.REC.1396.824. Existing administrative data were used to data collection. In case of home visits and interview, we obtained agreement of study participants using verbal consent. Because of lack of any invasive/ noninvasive procedures on participants and condition of the study setting, we preferred verbal instead of written consent form to report the history of their children’s immunization. Protocol of this study has been approved by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences as well.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Manoochehr Karami, Email: ma.karami@umsha.ac.ir.

Salman Khazaei, Email: salman.khazaei61@gmail.com.

Abbas Babaei, Email: babaeiabas@yahoo.com.

Fatemeh Abdoli Yaghini, Email: fathemehyaghini@yahoo.com.

Mohammad Mehdi Gouya, Email: mgouya57@gmail.com.

Seyed Mohsen Zahraei, Phone: +982181455011, Email: zahraeicdc@gmail.com, Email: zahraeicdc@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Hinman AR, Orenstein WA, Schuchat A. Control CfD, prevention. Vaccine-preventable diseases, immunizations, and MMWR: 1961-2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl 4):49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National immunization committee. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Schedule and guideline of immunization 8 th ed. Tehran: Zarak; 2015.

- 3.Klaucke DN, Buehler JW, Thacker SB, Parrish RG, Trowbridge FL, Berkelman RL. Guidelines for evaluating surveillance systems. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37(Suppl 5):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahraei SM, Eshrati B, Gouya MM. Is there still an immunity gap in high-level national immunization coverage, Iran? Archives of Iranian medicine. 2014;17(10):698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poorolajal J, Khazaei S, Kousehlou Z, Bathaei S, Zahiri A. Delayed vaccination and related predictors among infants. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(10):65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch-Capblanch X, Ronveaux O, Doyle V, Remedios V, Bchir A. Accuracy and quality of immunization information systems in forty-one low income countries. Tropical Med Int Health. 2009;14(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Heath Organization. Global framework for immunizatin monitoring and surveillance 2007. Available from: www.who.int/immunization/documents/en. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.WorldHealthOrganization. The immunization data quality self-assessment (DQS) tool. Avaliable at: [http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69034/1/WHO_IVB_05.04.pdf]. 2005.

- 9.Khazaei S, Ayubi E, Mansori K. High immunization coverage in children as one of the major achievements for the health system in Iran. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;4(7):2167–2169. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izadi S, Zahraie S-M, Sartipi M. An investigation into a measles outbreak in Southeast Iran. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moghadam M, Afsarkazerooni P, Ebrahimi M, Soltani M, Razmpoor A, Pirasteh E, et al. Measles outbreak in south of Iran, where vaccine coverage was high: a case-series study. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(3):375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronveaux O, Rickert D, Hadler S, Groom H, Lloyd J, Bchir A, et al. The immunization data quality audit: verifying the quality and consistency of immunization monitoring systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(7):503–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronveaux O, Rickert D, Hadler S, Groom H, Lloyd J, Bchir A, Birmingham M. The immunization data quality audit: verifying the quality and consistency of immunization monitoring systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:503–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Adamki M, Asamoah D, Riverson K. Assessment of data quality on expanded Programme on immunization in Ghana: the case of new Juaben municipality. J Health Med Informat. 2015;6:196. doi: 10.4172/2157-7420.1000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chahed MK, Bellali H, Alaya NB, Ali M, Mahmoudi B. Auditing the quality of immunization data in Tunisia. Asian Pacific journal of tropical disease. 2013;3(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(13)60014-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward K, Mugenyi K, Benke A, Luzze H, Kyozira C, Immaculate A, et al. Enhancing workforce capacity to improve vaccination data quality, Uganda. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(Suppl 1):S85. doi: 10.3201/eid2313.170627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Y, Zhang X, Li Q, Chen Y. Auditing the immunization data quality from routine reports in Shangyu District, East China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1158. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onta S, Sabroe S, Hansen E. The quality of immunization data from routine primary health care reports: a case from Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13(2):131–139. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freund PJ, Kalumba K. Monitoring and evaluation of primary health care in rural Zambia: a comparative study. Scand J Soc Med. 1985;13(4):137–146. doi: 10.1177/140349488501300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle SE, Wallace AS, MacNeil A, Mustafa M, Gasasira A, Ali D, et al. Limitations of using administratively reported immunization data for monitoring routine immunization system performance in Nigeria. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(suppl_1):S523–SS30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Accuracy ratio of pentvalent 3 & MMR1 register in the community (PDF 52 kb)

Accuracy ratio of pentvalent 3 and MMR1vaccines (PDF 9 kb)

Standard questions to assess the quality of the monitoring system (PDF 139 kb)

Standard questions to assess the quality of the monitoring system (PDF 200 kb)

Timeliness and completeness of Pentavalent 3 and MMR1vaccines reporting (PDF 12 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.