Abstract

Background

Poor patient understanding of atrial fibrillation (AF) may contribute to underuse of anticoagulation. There are no validated instruments to measure patient knowledge in Asian cohorts. This study aims to validate a disease-specific questionnaire measuring the level of understanding of AF and its treatment among patients with AF in Singapore.

Methods

A 10-item interviewer-administered questionnaire was created based on previously published questionnaires. Face and content validity were assessed. 165 participants were identified by convenience sampling at cardiology clinics of a tertiary hospital. The questionnaire was administered in either English (n = 53) or Mandarin (n = 112). Exploratory factor analysis was performed using principal component method. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Results

Face validity was tested by surveying 10 cardiologists who could all identify what the questionnaire was designed to measure. Mean content validity ratio across items was 0.9. Participants were 68.7 (SD 10.5) years old. 55.8% were male. 95.2% were on oral anticoagulation. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.67 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.01). Four factors were retained based on the eigenvalue > 1. These were knowledge of the following: disease characteristics, disease-specific treatment, role of treatment in symptom management and treatment mechanisms. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71).

Conclusions

A questionnaire on the knowledge of AF and its treatment was validated in a cohort of Asian patients in English and Mandarin. It allows quantification of patient knowledge and may be useful in Asian populations to assess the efficacy of interventions to improve patient understanding of AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, patient knowledge, questionnaire, psychometric

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) have been shown to have poor understanding of their disease and treatment. Objective instruments to measure the level of knowledge of AF among patients have been designed and validated in European populations.

What does this study add?

This is the first questionnaire that has been validated in English and Mandarin that can be used in an Asian cohort to objectively measure the level of knowledge of AF.

How might this impact clinical practice?

This knowledge questionnaire can potentially facilitate the development and implementation of patient-centred education interventions, which may lead to improved patient outcomes.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinically significant heart rhythm disorder in Singapore,1 with an estimated overall prevalence of 1.5%.2 With ageing populations, it is predicted that the number of patients with AF will increase by twofold over the next 50 years.3 This poses a challenge for healthcare systems globally as AF is associated with increased rates of heart failure, cardioembolic stroke4 and translates to a poorer quality of life,5 greater hospital costs6 and higher mortality. There is thus an incentive for healthcare systems to focus on strategies to reduce and prevent the development of complications of AF.

Anticoagulation, be it warfarin or novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), is a well-established means of reducing stroke risk.7 Warfarin has been shown to reduce stroke risk by 65%, whereas NOACs have been shown to be equal if not more efficacious.8 9 Although the benefits of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF are well established, its underutilisation is also widely reported, with less than half of patients with AF receiving anticoagulation.10 Identifying and overcoming barriers to treatment are areas of active research.

Educational intervention in chronic diseases has been shown to significantly improve knowledge, symptom monitoring, medication use and compliance, thus leading to better disease control. Clark et al 11 demonstrated in a meta-analysis that the most effective intervention programmes for patients with heart failure involved improving patient knowledge of heart failure, which translated to better disease control. This has been shown in patients with AF as well.12–14 Several studies have shown that patients with AF have poor understanding of their disease and its treatment.15–17 An objective method to measure the level of knowledge among patients with AF would better direct educational resources and help in assessing the efficacy of interventions. Such instruments have previously been studied and validated in European populations.18

Despite a comparable prevalence of AF in Asian populations and rapidly progressing health literacy, there have been few studies19 assessing the knowledge of these patients, and no validated instrument that allows us to do so reliably. This study therefore aims to validate an AF knowledge scale, both in Mandarin and in English, for the multiethnic and multilingual Asian population of Singapore.

Materials and methods

Design and development of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in three phases: (1) literature review and first construction, (2) testing for face validity and content validity and (3) factor analysis and testing of internal consistency. The scope of this work is limited to face and content validity testing as well as construct validity testing.

The questionnaire was created after a literature review resulting in in-depth analysis of four previous studies by Hendriks et al,20 Aliot et al,21 Koponen et al 22 and Lane et al,12 which all aimed to assess knowledge of AF in patients.

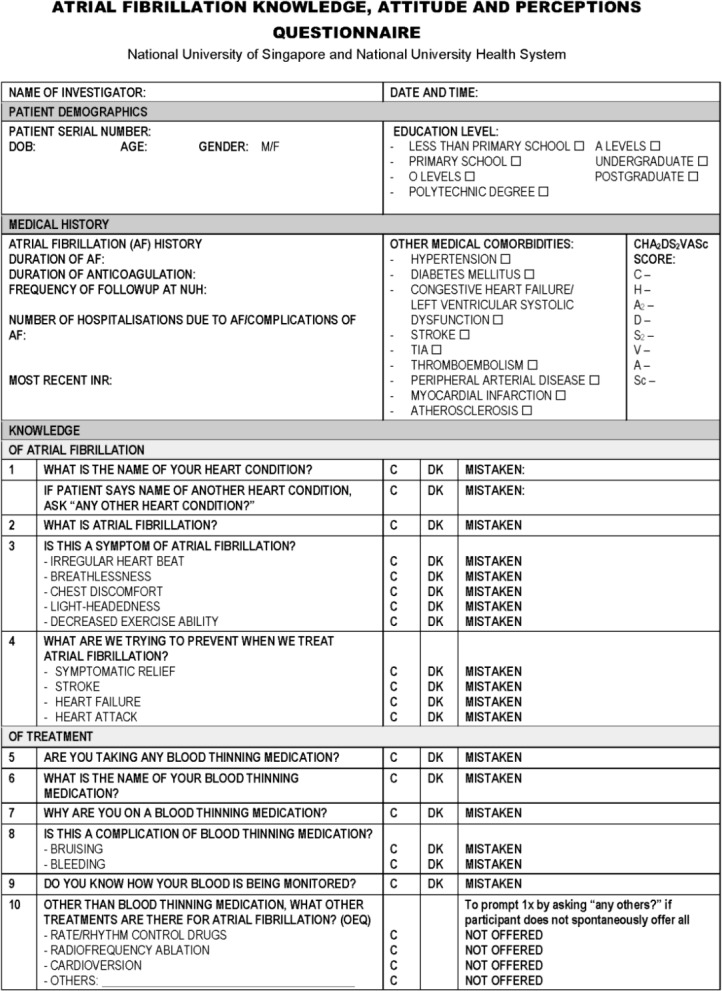

The questionnaire was designed to encompass the following: (1) knowledge of the disease and (2) knowledge of treatment. The questionnaire (figure 1) consists of 10 items that were grouped into the following categories: AF in general (two items: Q1 and Q2), symptoms of AF (one item: Q3) and AF treatment including aims, options and complications (seven items: Q4–Q10). A Mandarin version (online supplementary file) was developed through forward and backward translation with accredited bilingual translators working independently.

Figure 1.

English version of questionnaire. AF, atrial fibrillation; INR, international normalised ratio; NUH, National University Hospital; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

heartasia-2018-011143supp001.tiff (209.8KB, tiff)

Patient demographic data were collected by interviewing patients and through electronic medical records. These included age, gender, education level and medical history pertaining to duration of AF, duration of anticoagulation, frequency of follow-up, number of hospitalisations due to AF and complications of AF, most recent international normalised ratio, and presence of other medical comorbidities (constituents of the CHA2DS2-VASc score).

Validity

Face and content validity were assessed by presenting the questionnaire to 10 cardiologists from a single tertiary hospital who were active in the clinical care of patients with AF.

Face validity was tested by surveying the cardiologists on the apparent intent of the questionnaire while content validity was measured using Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio23 by inviting them to label each item of the questionnaire as ‘essential’, ‘useful but not essential’ or ‘not useful or essential’. Each of them was also asked for their opinion regarding the readability and comprehensibility of the questionnaire as a whole. The items of the questionnaire were then reworded based on the feedback obtained.

Construct validity was determined by performing exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. For the set of 10 items contained in the questionnaire, two measures were obtained to determine the suitability of performing a factor analysis: the value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and the statistical significance of the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Obtaining an adequate KMO value (ie, >0.5) and rejecting the null hypothesis (ie, statistically significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity value) would indicate that performing a factor analysis was appropriate. The KMO test measures the sampling adequacy and is a measure of the strength of the relationship between variables. The KMO measure should be greater than 0.5 for factor analysis to proceed. The null hypothesis is that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. The null hypothesis also needs to be rejected before proceeding with factor analysis. Rejection of the null hypothesis suggests that all the variables correlate sufficiently to provide an adequate basis for factor analysis. After determining the suitability for factor analysis, the factor analysis by principal component method with varimax rotation (which assumes no correlation between the factors in the analysis) was completed and factor loadings of at least 0.3 were considered acceptable.24

Reliability

Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. An acceptable value for this coefficient is at least 0.70. A value between 0.15 and 0.50 confirms the unidimensionality of the scale.

Participant recruitment

A total of 165 participants with AF were identified by convenience sampling in the cardiology outpatient clinics of a tertiary academic hospital. All patients with a known diagnosis of AF were approached to participate in the questionnaire. Of these, 53 participants completed the questionnaire in English and 112 completed it in Mandarin based on their preference of language. The questionnaire was verbally administered by trained interviewers who had undergone a standardisation course.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (V.22, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Demographic characteristics were recorded and divided into categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were used to present the frequencies of demographic characteristics within each category, which were subsequently expressed as a percentage of the total number of respondents per characteristic. Similarly, responses for items 1–9 in the questionnaire were dichotomised into ‘correct’ and ‘mistaken/do not know’ categories. These were analysed using descriptive statistics as well.

Statement of ethical publishing

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the National Healthcare Group, Domain Specific Review Board, Singapore, prior to participant recruitment and data collection and analysis. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Face and content validity

All 10 cardiologists surveyed identified correctly that the questionnaire intended to measure the level of understanding of AF and its treatment. Mean content validity ratio across items according to Lawshe’s content validity rule was 0.9 which was consistent with good content validity.

Demographics

Interview participants were 68.7 (SD 10.5) years old with a slight preponderance of men (table 1). Two-thirds of them did not progress beyond primary school education. Median CHA2DS2VASc score was 4 (25th –75th centiles 3–5), 92.0% who had a score of 2 and above. There was a high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. Most (95.2%) were on oral anticoagulation. All 165 patients were able to complete the interview.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of total patient population

| Demographic | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <65 | 50 | 30.3 |

| 65–74 | 62 | 37.6 |

| 75 and above | 53 | 32.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 92 | 55.8 |

| Female | 73 | 44.2 |

| Educational level | ||

| Less than primary school | 67 | 40.6 |

| Completed primary school | 43 | 26.1 |

| Completed O Levels | 31 | 18.8 |

| Completed A Levels | 4 | 2.4 |

| Completed polytechnic degree | 9 | 5.5 |

| Completed undergraduate | 8 | 4.8 |

| Completed postgraduate | 1 | 0.6 |

| Duration of medication use | ||

| Total number on medication | 157 | 95.2 |

| <1 year | 55 | 33.3 |

| 1–5 years | 62 | 37.6 |

| 5–10 years | 25 | 15.2 |

| >10 years | 15 | 9.1 |

| Risk factors for stroke | ||

| Hypertension | 129 | 78.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 | 40.0 |

| Congestive heart failure | 59 | 35.8 |

| Previous stroke | 26 | 15.8 |

| Previous TIA | 15 | 9.1 |

| Thromboembolism | 0 | 0.0 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 25 | 15.2 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 36 | 21.8 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 111 | 67.3 |

| Median CHA2DS2VASc score | 4 |

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analysis by principal component method yielded a KMO measure of 0.67. The test of hypothesis using the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p value<0.01). Four factors were retained based on Kaiser’s criterion that suggests retention of factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.25 Altogether, these four factors explained 64.1% of the variance. Factors 1–4 explained 29.3%, 12.7%, 11.9% and 10.3% of the variance, respectively.

The rotated component matrix (table 2) shows the factor loadings for each component (factor), taking note of all factor loadings higher than 0.3. The higher the absolute value of the loading, the greater that item contributes to the factor. Three items (Q8, Q9 and Q10) loaded on Factor 1; four items (Q3, Q5, Q6 and Q7) on Factor 2; two items (Q1 and Q2) on Factor 3 and one item (Q4) on factor 4. These four factors were named as follows: Factor 1 (Q8, Q9 and Q10), knowledge of treatment mechanisms; Factor 2 (Q3, Q5, Q6 and Q7), knowledge of disease-specific treatment; Factor 3 (Q1 and Q2), knowledge of disease characteristics and Factor 4 (Q4), role of treatment in symptom management.

Table 2.

Rotated component matrix

| Component/factor | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Item 1 | 0.026 | 0.171 | 0.774 | −0.065 |

| Item 2 | 0.182 | −0.058 | 0.831 | 0.013 |

| Item 3 | −0.149 | 0.490 | 0.222 | 0.219 |

| Item 4 | 0.041 | 0.110 | −0.015 | 0.890 |

| Item 5 | 0.158 | 0.735 | −0.160 | −0.011 |

| Item 6 | 0.203 | 0.600 | 0.148 | −0.313 |

| Item 7 | 0.307 | 0.627 | 0.097 | 0.118 |

| Item 8 | 0.387 | 0.323 | 0.087 | −0.367 |

| Item 9 | 0.951 | 0.135 | 0.064 | −0.025 |

| Item 10 | 0.944 | 0.172 | 0.144 | 0.002 |

Extraction method: factor analysis by component method.

Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalisation.

Factor loadings higher than 0.3 are in bold.

* Rotation converged in six iterations.

Reliability

Internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s alpha=0.71), indicating that all items were correlated. Removal of item 4 improved the Cronbach’s alpha to 0.73; nevertheless, this item was retained in view of its value to daily practice and the small difference in the value of Cronbach’s alpha.

Questionnaire responses

Responses are detailed in table 3.

Table 3.

Participant responses

| Item | Question asked | Patient answer | Percentage (%) |

| 1 | What is the name of your heart condition? | Correct | 16.4% |

| Mistaken | 40.6 | ||

| Do not know/no answer provided | 43.0 | ||

| 2 | What is atrial fibrillation? | Correct | 16.4 |

| Mistaken/do not know | 82.4 | ||

| 3 | Is this a symptom of atrial fibrillation? | ||

| Irregular heart beat | Correct | 68.5 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 31.5 | ||

| Breathlessness | Correct | 60.3 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 39.5 | ||

| Chest discomfort | Correct | 52.1 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 47.9 | ||

| Light-headedness | Correct | 42.4 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 57.6 | ||

| Decreased exercise ability | Correct | 63.6 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 36.4 | ||

| 4 | What are we trying to prevent when we treat atrial fibrillation? | ||

| Symptomatic relief | Correct | 63.0 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 37.0 | ||

| Stroke | Correct | 12.7 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 87.3 | ||

| Heart failure | Correct | 57.6 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 42.4 | ||

| Heart attack | Correct | 43.6 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 56.4 | ||

| 5 | Are you taking any blood thinning medication? | Correct | 92.7 |

| Mistaken/do not know | 7.3 | ||

| 6 | What is the name of your blood thinning medication? | Correct | 54.5 |

| Mistaken/do not know | 45.5 | ||

| 7 | Why are you on a blood thinning medication? | Correct | 68.5 |

| Mistaken/do not know | 31.5 | ||

| 8 | Is this a complication of blood thinning medication? | ||

| Bruising | Correct | 68.5 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 31.5 | ||

| Bleeding | Correct | 74.5 | |

| Mistaken/do not know | 25.5 | ||

| 9 | Do you know how your blood is being monitored? | Correct | 66.1 |

| Mistaken/do not know | 33.9 | ||

| 10 | Other than blood thinning medications, what other treatments are there for atrial fibrillation? | Rate/rhythm control medications | 11.5 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 7.3 | ||

| Cardioversion | 1.2 | ||

| Others: lifestyle modifications, control of other chronic diseases | 11.5 | ||

Knowledge of disease characteristics

Participants generally demonstrated poor knowledge of the disease, with a minority (16.4%) aware of the name of the heart condition they had and were on follow-up for. When offered the term ‘atrial fibrillation’, few (16.4%) knew what it was. However, majority of participants were able to identify common symptoms of their cardiac condition.

Knowledge of role of treatment in symptom management

Majority of participants identified that treatment is directed towards cardiac complications of AF (symptomatic relief and heart failure). However, they were also of the mistaken belief that treatment of AF lowers risk of myocardial infarction. Notably, only 12.7% were aware that one of the main aims of AF treatment was stroke prevention.

Knowledge of disease-specific treatment

Most participants (92.7%) correctly stated whether or not they were on anticoagulation. Of these, only 54.5% named their anticoagulant correctly.

Knowledge of treatment mechanisms

A majority of participants were able to correctly identify complications of anticoagulation and that the adequacy of anticoagulation was being monitored by blood tests. There was overall poor understanding of alternative therapies available for AF, with 75.3% not knowing of any other forms of therapy apart from anticoagulation.

Discussion

This paper reports the development and validation of a questionnaire that can be used in an Asian cohort to objectively measure the level of knowledge of AF. Importantly, this questionnaire was administered in English and Mandarin, allowing the objective measurement of the level of knowledge among patients with AF in a multilingual, multiethnic Asian population. The participants’ responses also highlight the low levels of knowledge among patients with AF which may represent a potential target for intervention.

The questionnaire had a high mean content validity ratio. The four factors identified using factor analysis appear to be subsets of the original two components of knowledge the questionnaire was designed to assess. Internal consistency of the questionnaire was good in spite of a small number of items. The results are comparable to the validated AF knowledge scale developed by Hendriks et al which has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.58 and good face, content and construct validity.20

Thus far, this is the only study that has validated an instrument to assess patient’s knowledge of AF in a multilingual Asian patient population. It is the first AF knowledge questionnaire validated in Mandarin. As this is a short questionnaire of 10 items, it can be administered by trained clinic staff within 5 min prior to consultations.

The knowledge this cohort of patients with AF had of their disease, its complications and its treatment was generally poor. Similar findings suggesting poor patient knowledge of AF have also been shown by other studies. Lip et al 18 showed that only 63% of 119 patients studied were aware of their cardiac condition and only 52% were aware of the reasons for initiating oral anticoagulation therapy. The AF aware group also showed in 2010 that 25% of 825 patients with AF studied were unable to explain AF.21 Due to different methods of testing for patient knowledge, direct comparison of results with these studies is not possible, but it highlights that this study’s findings are not unique and probably typical of patients with AF worldwide.

The low level of patient knowledge of AF raises several possible gaps, such as physician communication with patients, language barriers (especially in a multiethnic society) and the failure to allocate adequate time and resources to patient education. In this study, the relatively low level of formal education may also be a contributing factor. It does, however, point to important targets for therapeutic interventions for improving patient knowledge to promote patient empowerment and enable self-management, which may, in turn, translate into improved compliance with treatment.12 Studies by Howitt et al 13 and Protheroe et al 14 showed that patient’s’ knowledge and beliefs about their disease and treatment are important factors influencing their compliance with anticoagulation. As such, various centres managing AF have invested in specialised AF clinics which dedicate resources to patient education to promote ‘self-management’ of AF.26 27

An instrument that can measure patients’ level of knowledge of a disease is important to identify patients with the greatest education need and evaluate the effect of education interventions. Previously validated questionnaires by Koponen et al 22 and Hendriks et al 20 were written and administered in English and Dutch, respectively to a Western population and may not be fully applicable to the local population in Singapore where a large proportion of older patients are unable to communicate in English.

This study has several limitations. First, with regard to questionnaire administration, an interviewer is required to administer the questionnaire, necessitating additional manpower and potentially resulting in differences in interpretation of patient responses. This was minimised by ensuring interviewers undergo a standardisation course. The questionnaire was also designed in a manner that requires the interviewer to review the participants’ medical records to determine whether their responses are correct, requiring more effort on the part of the interviewer. Second, while English and Mandarin are the most commonly spoken languages, there is a significant proportion of patients in the population that do not speak either. Third, the questionnaire was only tested in a single centre in an outpatient setting. When using the questionnaire in a different context, it is advised to further validate the questionnaire. For example, its face validity may be further increased by including different experts. It would also be useful to test the relationship between disease knowledge and other variables (eg, self-management behaviour) to assess the usefulness of the questionnaire to obtain treatment objectives. Finally, the validation process was limited to face and content validity testing as well as construct validity testing. Confirmatory factor analysis is an additional step that can be performed. In addition, test–retest reliability and agreement statistics would be important psychometric properties to establish. The methodological quality of the questionnaire can also be further assessed in accordance with the nsensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments checklist.28

Conclusions

The present study reports the development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring patient knowledge of AF in Singapore. As this is the first AF knowledge questionnaire validated in Mandarin, it is of relevance to the Asia Pacific region, both in predominantly Mandarin-speaking countries and also in countries with significant numbers of Chinese immigrants. This knowledge questionnaire can potentially facilitate the development and implementation of patient-centred education interventions, which may lead to improved patient-related outcomes such as patient empowerment and self-management. The low levels of patient knowledge found in this study suggest the pressing need to improve this aspect of AF management.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients, nurses and cardiologists for their participation and support. A special word of thanks to Dr Leong Wai Siang for his contribution to the development of the Mandarin questionnaire.

Footnotes

HJMV and TWL contributed equally.

Contributors: All authors were involved in the conception and design of the work, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. WL and RH were responsible for data collection and drafting the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ministry of Health Management of atrial fibrillation. Clinical practice guidelines. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yap KB, Ng TP, Ong HY. Low prevalence of atrial fibrillation in community-dwelling Chinese aged 55 years or older in Singapore: a population-based study. J Electrocardiol 2008;41:94–8. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. . Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (atria) study. JAMA 2001;285:2370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, et al. . A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med 2002;113:359–64. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thrall G, Lip GYH, Carroll D, et al. . Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation. Chest 2007;132:1259–64. 10.1378/chest.07-0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ringborg A, Nieuwlaat R, Lindgren P, et al. . Costs of atrial fibrillation in five European countries: results from the Euro Heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Europace 2008;10:403–11. 10.1093/europace/eun048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. . Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:492–501. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Madzak A, Larsen TB, Lane DA, et al. . Composite end point analyses of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants compared with Warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2015;13:1155–63. 10.1586/14779072.2015.1086643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dentali F, Riva N, Crowther M, et al. . Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation 2012;126:2381–91. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.115410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, Teo KK, et al. . Why do patients with atrial fibrillation not receive warfarin? Arch Intern Med 2000;160:41–6. 10.1001/archinte.160.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clark AM, Wiens KS, Banner D, et al. . A systematic review of the main mechanisms of heart failure disease management interventions. Heart 2016;102:707–11. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lane DA, Ponsford J, Shelley A, et al. . Patient knowledge and perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulant therapy: effects of an educational intervention programme. the West Birmingham atrial fibrillation project. Int J Cardiol 2006;110:354–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howitt A, Armstrong D. Implementing evidence based medicine in general practice: audit and qualitative study of antithrombotic treatment for atrial fibrillation. BMJ 1999;318:1324–7. 10.1136/bmj.318.7194.1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Protheroe J, Fahey T, Montgomery AA, et al. . The impact of patients' preferences on the treatment of atrial fibrillation: observational study of patient based decision analysis. BMJ 2000;320:1380–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Desteghe L, Engelhard L, Raymaekers Z, et al. . Knowledge gaps in patients with atrial fibrillation revealed by a new validated knowledge questionnaire. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:906–14. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alphonsa A, Sharma KK, Sharma G, et al. . Knowledge regarding oral anticoagulation therapy among patients with stroke and those at high risk of thromboembolic events. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:668–72. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith MB, Christensen N, Wang S, et al. . Warfarin knowledge in patients with atrial fibrillation: implications for safety, efficacy, and education strategies. Cardiology 2010;116:61–9. 10.1159/000314936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lip GYH, Kamath S, Jafri M, et al. . Ethnic differences in patient perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation therapy: the West Birmingham atrial fibrillation project. Stroke 2002;33:238–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee VWY, Tam CS, Yan BP, et al. . Barriers to warfarin use for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation in Hong Kong. Clin Cardiol 2013;36:166–71. 10.1002/clc.22077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hendriks JML, Crijns HJGM, Tieleman RG, et al. . The atrial fibrillation knowledge scale: development, validation and results. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:1422–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aliot E, Breithardt G, Brugada J, et al. . An international survey of physician and patient understanding, perception, and attitudes to atrial fibrillation and its contribution to cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. Europace 2010;12:626–33. 10.1093/europace/euq109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koponen L, Rekola L, Ruotsalainen T, et al. . Patient knowledge of atrial fibrillation: 3-month follow-up after an emergency room visit. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:51–61. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol 1975;28:563–75. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown JD. Questions and answers about language testing statistics: choosing the right number of components or factors in pCa and EFA. Shiken: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter 2009;13:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ledesma RD, Valero-Mora P. Determining the number of factors to retain in EFA: an easy-to-use computer program for carrying out Parellel analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007;12:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tran HN, Tafreshi J, Hernandez EA, et al. . A multidisciplinary atrial fibrillation clinic. Curr Cardiol Rev 2013;9:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qvist I, Hendriks JML, Møller DS, et al. . Effectiveness of structured, hospital-based, nurse-led atrial fibrillation clinics: a comparison between A real-world population and a clinical trial population. Open Heart 2016;3:e000335 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. . The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010;19:539–49. 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

heartasia-2018-011143supp001.tiff (209.8KB, tiff)