Abstract

Google Play Store was used to search for eye care-related applications the android simulator using various general terms related to eye care to review and categorize various interactive eye care-related applications in android platform from the details available in the application website. Data collected from application description and application developer's webpage include target audience, category of apps, estimated number of downloads, average user rating, involvement of eye care professionals in developing the application, and cost of the app. All these data were collected only from the details provided in the application website considering on online user perspective and the developers were not contacted to collect any other details. In total, 475 applications were identified and grouped into 13 categories depending on the type of service the application provide. Out of which, only 107 (22.53%) applications had mentioned about the eye care professional involvement in their design or development of the application. The applications were also stratified according to the target audience, and many had no user rating with very few downloads. The lack of evidence-based principles and standardization of application development should be taken into consideration to avoid its negative impact on the community, especially in eye care.

Keywords: Android-based applications, eye care, mobile applications, smart-phones

Introduction

Mobile technology has the potential to make the availability of health care to the public.[1] Technological advances with increasing number of available mobile applications (app), as well as reduced costs, led to a massive use of smartphones.[2] A survey of mobilephone ownership in the United Kingdom among 474 health-care professionals including 161 General Medical Council registered doctors, 223 Nursing and Midwifery Council registered nurses and midwives, and 76 registered allied health professionals with average of 9.7 years professional experience showed, 99% of them possess a mobile phone, of which 81% was a smartphone and 46% of these professionals use the internet in accessing the health information.[1] Medical knowledge being ever-changing, Mobile Decision Support System plays a major role in accurate diagnosis of disease thus optimizing the health care.[3]

Use of mobile phones even in the economically underdeveloped countries allowed them to bypass the fixed-line technology and gain easy access to the mobile phone-based technologies.[4]

With a growing trend of use of smartphones and smartphone-based applications in almost all areas of clinical practice including the modern eye care foster the public health-care sector.[5,6,7] Although the availability of these applications is limitless, the concern about regulation in its development, experts involvement usage, and data confidentiality are need to be addressed and authenticated.[8,9] Mobile operating system (OS) survey showed android takes 87% of the market followed by iPhone OS 12% and other OSs take the remaining 1% of the market.[10] Although android shares the major platform in mobile application, not many studies are available about the utilization of android-based mobile applications in eye care.

Materials and Methods of Searching for Applications

To install the android-based app, free android simulator (Droid 4X)[11] incorporated with Google Play Store was installed on the Windows 7 laptop. Search for app was performed, between May 8, 2017 and May 15, 2017 for android eye care – specific commercial apps, using the general eye care terms “ophthalmology,” “ophthalmology app,” “ophthalmology book,” “Ophthalmologist,” “Optometry,” “Optometry app,” “Optometry book,” “Optometrist,” “Eye care,” “Low vision,” “Binocular vision,” “Amblyopia games,” “Orthoptics,” “Contact lens,” and “Dispensing.” The use of logical operators such as AND and OR was not supported by Google Play Store. Hence, we could not perform the search of a combination of search terms.

To select an app from the results obtained by our search, the description of all the app was thoroughly read, considering only those that has a description in English or with English translation. The exclusion criteria were apps related to any gaming for entertainment and conference or event registration. The topic and usage of these apps in eye care were analyzed and considered from the description given for each app.

All the details were collected either from the app or from their website and the app developers were not contacted to collect any details. If there was inadequate description, the app was installed in a computer through the android simulator to gather more details. The data collected about each app include target audience, the category of apps, estimated number of downloads, average user rating, mention of details regarding involvement of eye care professionals, and the cost of the app.

The apps were grouped into 13 categories such as

Educational materials

Clinical calculator

Vision testing by various means

Appointments of the patient with the doctor

Eye exercises

Low vision management

Social networking

Patient record management

Visual hygiene

Miscellaneous (apps promoting an institute/product by only advertisement, online purchasing, guidelines, location of clinics in a particular area)

Contact lens care and maintenance

Entrance examination preparation

Telemedicine.

And the target audiences were divided as follows:

Optometrist

Ophthalmologist

Public

General practitioners

Medical and Allied Health Science (AHS) Students

Opticians.

Results

Categories of the app

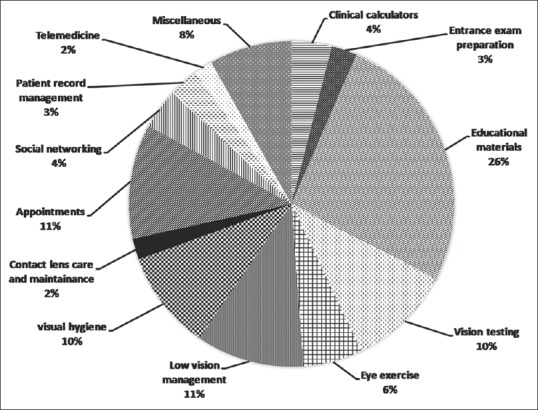

Four hundred and seventy-five apps were identified and grouped into 13 categories [Figure 1] depending on the type of service the app provide. 124 (26.1%) apps were placed under the category “Educational materials” to various targeted population, out of which 8 (6.45%) apps has education and reference material targeting optometrists, 54 (43.54%) apps were targeting ophthalmologists, 18 (14.51%) apps were targeting general public individuals, 18 (14.51%) apps targeted general practitioners, 11 (8.87%) were under “Medical, and AHS students,” 8 (6.45%) apps were targeting opticians, 6 (4.83%) apps targeted both optometrists and ophthalmologists, 1 (0.8%) app targeted optometrists and opticians. 19 (4%) apps were under “Clinical calculators” out of which 9 (47.36%) apps targeted optometrists, 2 (10.52%) apps targeted ophthalmologists, 1 (5.26%) app targeted general public, 1 (5.26%) app targeted optometrists and ophthalmologists, 4 (21.05%) apps targeted optometrists and opticians, 2 (10.52%) apps targeted optometrists. 49 (10.31%) apps were under “Vision test by various mean” provided various means of vision testing out of which 4 (8.16%) apps targeted optometrists, 5 (10.20%) apps targeted ophthalmologists, 30 (61.22%) apps targeted general public, 2 (4.08%) apps targeted general practitioners, 6 (12.24%) apps targeted optometrists and ophthalmologists, 2 (4.08%) apps targeted optometrists ophthalmologists and opticians. 54 (11.36%) apps were placed under “Appointments of the patient with the doctor” which aids in taking appointment by the patient with the various clinic and clinical practitioners. 28 (5.89%) apps were placed under “Eye exercises” which provides various means games with various difficulty level aiding in training for lazy eye both with and without visual reality box. 51 (10.73%) apps were under “Low vision management” targeting visually impaired population to aid in their various activities of daily living. 19 (4%) apps were under “Social networking” providing a platform for the professionals to share their thoughts and provide contacts remainder and updates about the various conferences. 14 (2.94%) apps were placed under “Patient record management” which provides a platform for patient, optometrist, ophthalmologist, general practitioners, and opticians to manage the patient records and billing spectacles, frame, lenses contact lens. 47 (9.89%) apps were placed under “Visual hygiene” provides a remainder when using a system for long term, notification for blinking and reduction of blue light emission from the screen. 10 (2.1%) apps were placed under “Contact lens care and maintenance” provided remainder about change of solution change of contact lens, instructions about the contact lens usage (insertion and removal). 12 (2.52%) apps were under “Entrance examination preparation” provided various study material, model question papers and flash cards for people willing to appear for Optometry admission test. 9 (1.89%) apps under “Telemedicine” provided a platform between patient and the professionals in reviewing the reports and medication and also provided real-time consultation based on the response by the patient to the various targets in the app, and 39 (8.21%) apps were placed under “Miscellaneous” which included (apps promoting a institute/product by only advertisement, online purchasing, guidelines, and location of clinics in a particular area).

Figure 1.

Stratification of apps according to various categories

Target audience

Thirty-seven (7.78%) apps were designed with mainly targeting optometrist, 72 (15.15%) apps were targeting ophthalmologist, 289 (60.84%) apps were targeting general public, 26 (5.47%) apps were targeting general practitioners, 11 (2.31%) apps were targeting medical and AHS students, 9 (1.89%) apps were targeting optician, 15 (3.15%) apps targeted optometrist and ophthalmologist, 10 (2.1%) apps targeted optometrist and opticians, and 6 (1.26%) apps targeted optometrist, ophthalmologist, and opticians.

Downloaded volume

Although most of the apps were freely downloadable, few apps were pay and use version and few are free initially and had in-app purchases to potentially use the app, this could have possibly affected the download volume of the apps. Four (0.84%) apps had no downloads, 14 (2.94%) apps had 1–4 downloads, 13 (2.73%) apps had 5–9 downloads, 64 (13.47%) apps had 10–49 apps downloads, 48 (10.10%) apps had 50–99 downloads, 85 (17.89%) apps had 100–499 downloads, 45 (9.47%) apps had 500–999 downloads, 74 (15.57%) apps had 1000–4999 downloads, 23 (4.84%) apps had 5000–9999 downloads, 49 (10.31%) apps had 10,000–49999 downloads, 16 (3.36%) apps had 50,000–99,999 downloads, 19 (4%) apps had 100,000–499,999 downloads, 8 (1.68%) apps had 500,000–999,999 downloads, 9 (1.89%) apps had 1,000,000–4,999,999 downloads, 2 (0.42%) apps had 5,000,000–9,999,999 downloads, and 2 (0.42%) apps had more than 10,000,000 downloads.

Ratings of the app

Ninety-five (20%) apps had no rating, 8 (1.68%) apps had rating <1.9, 13 (2.73%) apps had 2-2.9 rating, 93 (19.57%) apps had 3–3.9 rating, 206 (43.36%) apps had 4–4.9 rating, and 60 (12.63%) apps had a rating of 5.

The cost of the app

Three hundred and sixty-three (76.42%) apps were available completely free of cost, 93 (19.57%) apps pay and use apps and 19 (4%) apps had been free initially and had in-app purchases to potentially use the app.

Involvement of qualified professionals

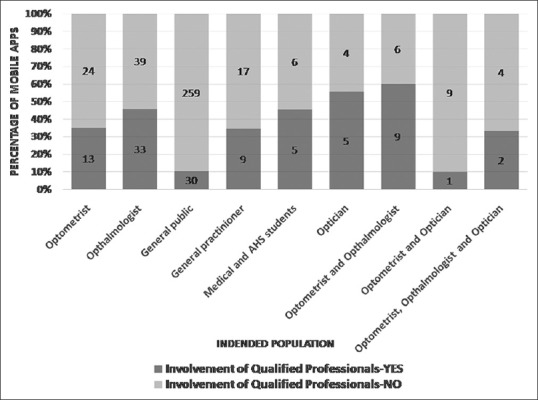

Out of 475 apps, only 107 (22.53%) apps had mentioned details of involvement of professionals in their design and development of the app; the remaining app had not mentioned those details. Out of those 107 apps, on stratifying [Figure 2] 13 (12.15%) apps were designed with mainly targeting optometrist, 33 (30.84%) apps were targeting ophthalmologist, 30 (28.04%) apps were targeting general public, 9 (8.41%) apps were targeting general practitioners, 5 (4.67%) apps were targeting medical and AHS students, 5 (4.67%) apps were targeting optician, 9 (8.41%) apps targeted optometrist and ophthalmologist, 1 (0.93%) app was targeting optometrist and opticians, and app targeted optometrist, 2 (1.87%) apps were targeting ophthalmologist and opticians. When stratifying according to the categories of the app 59 (55.14%) apps were under “educational materials”, 4 (3.74%) apps were under “clinical calculator”, 15 (14.01%) apps were under “Vision testing by various means”, 7 (6.54%) apps were under “Eye exercises”, 1 (0.93%) apps were under “low vision management”, 2 (1.87%) apps were under “Social networking”, 3 (2.8%) apps were under “patient record management”, 1 (0.93%) app was under “miscellaneous”, 3 (2.8%) apps were under “visual hygiene”, 8 (7.48%) apps were under “Entrance examination preparation”, 3 (2.8%) apps were under “telemedicine,” and 1 (0.93%) was under multiple categories.

Figure 2.

Provision of details regarding involvement of eye care professionals in the development of app

Discussion

Smartphones assist in the patient examination everywhere henceforth aiding the examiner in the emergency setting and also in the screening of large population.[9,12] The clinical converters and calculators reduce the time of the eye care professionals by assisting in the various conversions.[9]

Education app for patient makes it ideal providing information about the condition with video can help the patient to understand the condition which is difficult with discussion with the eye care professionals alone and few apps also help in maintaining their medical records and visual aids to check the progress of the disease.[2,9,12]

Development of education and reference material to professional and students is changing the learning process by the advent of smartphones as the education material is being distributed in a quick and effective manner. Smartphone applications eliminate the need to carry heavy books indeed gives the essential reference material on the go and also be as a decision support system in the clinics.[2,9,12,13,14,15]

Social networking between the professionals and the patient makes it easier for the professionals to share the different view of thoughts further help the patient to understand the condition better and eventually lead to better care regiments. The real-time discussion about the reports makes it possible for the patient not to present every time, thus treating the patient in a telemedicine fashion providing a remote diagnosis in low- and high-income community.[4,9] Various application is aiding the patient with low vision to manage their daily living activities, the application also helps in care regiments of contact lens and reduces the dry eye and other related conditions on the usage of mobile by increasing the blink rate, reducing the blue light exposure from the display by giving a notification.

Development of tools for maintaining the patient records indeed create demand in accessing these record remotely in a secured manner and also the advent of administration and management tools gives ease of access to management and referral in a telemedicine fashion within an affordable budget.[12]

Apps are becoming of increasingly greater relevance in modern eye care professional. The trend in the growing of technology and literature demonstrated the capacity of smartphones as useful clinical adjuncts, limitations of these apps need to be considered before integrating mobile apps into the day-to-day practice.[8,9,12] A notable difference in quality, accuracy, and professional involvement in these apps were noted in the literature. In our study, 22.53% of all apps had clearly documented professional involvement in app development giving an alarm for the governance and apps targeting the general population was also correlated.[7]

Although few mobile technologies are found to be clinically valid,[6,15,16,17,18] the lack of stipulated professional involvement in the development of eye care apps was found to be consistent with a study (37%) by Cheng et al.,[8] Similarly with other specialties such as colorectal (33%),[19] dermatology (33%),[20] and pain management (12%),[21] indicating the consistency of these issues across many medical specialties, supporting the clear need for governance and regulation of medical app development minimizing the risks to public health.

The use of smartphone application in Medicare is increasing as the day goes getting more involved in the modern eye care and this demonstrates its use in the eye care. Although the data regarding the last update of the apps could not be given in this paper, it was found while analyzing the description of the apps, most of the apps were found to be not updated for long period of time, and lack of restrictions for downloading other than the targeted audience, peer review, and validation of the apps were found. To avoid potential risk of misleading information, the details of eye care regiments as well as information about eye diseases mentioned in most of the apps are need to be validated and authenticated by eye care professional. Although the websites such as iMedicalApps address the need for substantiated reviews from experts in mobile health,[22] regulation and governance of Medicare apps is needed to avoid its negative impact on the community.[8,9,23,24,25]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.A Survey of Mobile Phone usage by Health Professionals in the UK. 2010. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.d4.org.uk/research/survey-mobile-phone-use-health-professionals-UK.pdf .

- 2.Zvornicanin E, Zvornicanin J, Hadziefendic B. The use of smart phones in ophthalmology. Acta Inform Med. 2014;22:206–9. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.206-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Torre-Díez I, Martínez-Pérez B, López-Coronado M, Díaz JR, López MM. Decision support systems and applications in ophthalmology: Literature and commercial review focused on mobile apps. J Med Syst. 2015;39:174. doi: 10.1007/s10916-014-0174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastawrous A, Armstrong MJ. Mobile health use in low- and high-income countries: An overview of the peer-reviewed literature. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:130–42. doi: 10.1177/0141076812472620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oluleye TS, Rotimi-Samuel A, Adenekan A. Mobile phones for retinopathy of prematurity screening in Lagos, Nigeria, sub-Saharan Africa. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016;26:92–4. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali ZC, Silvioli R, Rajai A, Aslam TM. Feasibility of use of a mobile application for nutrition assessment pertinent to age-related macular degeneration (MANAGER2) Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6:4. doi: 10.1167/tvst.6.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-Pérez B, de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M. Mobile health applications for the most prevalent conditions by the World Health Organization: Review and analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng NM, Chakrabarti R, Kam JK. IPhone applications for eye care professionals: A review of current capabilities and concerns. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:385–7. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chhablani J, Kaja S, Shah VA. Smartphones in ophthalmology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:127–31. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.94054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apple vs. android — A comparative study 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.android.jlelse.eu/apple-vs-android-a-comparative-study-2017-c5799a0a1683 .

- 11.Droid4XInstaller. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.dl.haima.me/download/DXDown/win/Z001/Droid4XInstaller.exe .

- 12.Bastawrous A, Cheeseman RC, Kumar A. IPhones for eye surgeons. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:343–54. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de la Torre-Díez I, Martínez-Pérez B, López-Coronado M, Díaz JR, López MM. Decision support systems and applications in ophthalmology: Literature and commercial review focused on mobile apps. J Med Syst. 2015;39:174. doi: 10.1007/s10916-014-0174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López MM, López MM, de la Torre Díez I, Jimeno JC, López-Coronado M. A mobile decision support system for red eye diseases diagnosis: Experience with medical students. J Med Syst. 2016;40:151. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0508-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López MM, López MM, de la Torre Díez I, Jimeno JC, López-Coronado M. MHealth app for iOS to help in diagnostic decision in ophthalmology to primary care physicians. J Med Syst. 2017;41:81. doi: 10.1007/s10916-017-0731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathipati AS, Wood EH, Lam CK, Sáles CS, Moshfeghi DM. Visual acuity measured with a smartphone app is more accurate than snellen testing by emergency department providers. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:1175–80. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phung L, Gregori NZ, Ortiz A, Shi W, Schiffman JC. Reproducibility and comparison of visual acuity obtained with sightbook mobile application to near card and snellen chart. Retina. 2016;36:1009–20. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aslam TM, Parry NR, Murray IJ, Salleh M, Col CD, Mirza N, et al. Development and testing of an automated computer tablet-based method for self-testing of high and low contrast near visual acuity in ophthalmic patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:891–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill S, Brady RR. Colorectal smartphone apps: Opportunities and risks. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e530–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton AD, Brady RR. Medical professional involvement in smartphone 'apps' in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:220–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosser BA, Eccleston C. Smartphone applications for pain management. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:308–12. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.101102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.iMedicalApps, Reviews of Medical Apps and Healthcare Technology. 2014. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.imedicalapps.com/

- 23.Lamirel C, Bruce BB, Wright DW, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Nonmydriatic digital ocular fundus photography on the iPhone 3G: The FOTO-ED study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:939–40. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidance for Industry and Food. 2016. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/…/UCM263366.pdf .

- 25.Natarajan S, Nair AG. Outsmarted by the smartphone! Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63:757–8. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.171502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]