Abstract

Introduction:

Choledochal cyst (CDC) is often associated with intrahepatic stones (IHSs) in children which necessitate their removal during excision. The endoscopic equipment needed for their clearance such as paediatric flexible cholangioscope and other advanced modalities are not freely available in resource-poor setups. We describe per-operative modified rigid cholangioscopy using rigid paediatric cystoscope for stone removal during open CDC excision.

Methods:

All children with CDC presenting with IHSs between January 2015 and December 2017 were included in the present study. IHSs were diagnosed by ultrasound/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). In these patients, after cyst excision by open technique, a 9 Fr paediatric cystoscope with 4 Fr working channel was inserted into the common hepatic duct for visualisation and clearance of stones from (intrahepatic bile ducts). Follow-up was done using liver function tests, ultrasound and MRCP (if needed). Patients underwent three monthly liver function test and ultrasound and if needed MRCP.

Results:

Six cases of CDC presenting with IHS were managed, and one case with post-R-en-Y IHS was treated with this technique. Rigid paediatric cystoscope with working channel and forceps was used. All cases were successfully managed, and one case was found to have intrahepatic duct stenosis was dilated.

Conclusion:

Per-operative rigid endoscopy using paediatric cystoscope is an easily available tool in most of the setups for the management of IHS associated with CDC in children.

Keywords: Children, choledochal cyst, endoscopy, intrahepatic stones

INTRODUCTION

Cyst excision followed by hepaticoenterostomy is the treatment of choice for choledochal cyst (CDC).[1] Approximately 18% of CDCs have associated intrahepatic stones (IHS) which need simultaneous management.[2] Removal of these IHSs is challenging and involves extraction by per-operative flexible cholangioscopy; an instrument not commonly available in resource-constrained settings.[3] In the absence of operative cholangioscopy, surgeons commonly adopt ‘blind’ technique of per-operative flushing for clearance of IHSs and debris. The risk of missed stones or incomplete clearance of debris is real and is reflected in many reports describing stones in intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBDs) during follow-up.[3] We circumvented this problem using paediatric cystoscope for per-operative rigid cholangioscopy for removal of IHS associated with CDC in children.

METHODS

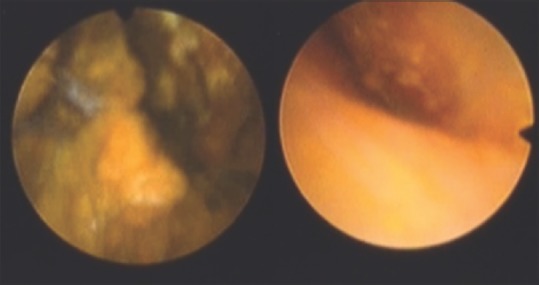

All children with CDC presenting between January 2015 and December 2017 were included in the present study. IHSs were diagnosed by ultrasound/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). In these patients, after cyst excision by open technique, a 10 Fr Paediatric Cystoscope with 5 Fr working channel was inserted into the common hepatic duct (CHD) for visualisation and clearance of stones from (IHBD) [Figure 1]. Soft stones and debris were cleared by high-flow saline irrigation using other two channels of the scope. The debris was cleared by the side of the scope and removed by suction after it came out of CHD. After irrigation, the residual stones were removed with 4 Fr grasper, and clearance was confirmed endoscopically [Figure 2]. Complete visualisation of both hepatic ducts was done to rule out intrahepatic stenosis. In case of stenosis, dilatation was done by Seldinger technique using a guidewire and polyvinyl chloride dilator. R-en-Y HJ was performed after endoscopic confirmation of debris and IHSs clearance from the IHBD.

Figure 1.

Paediatric 10 Fr rigid cystoscope with 5 Fr working channel, Make R-Wolf

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of intrahepatic duct before and after clearance

Follow-up was done using liver function tests, ultrasound and MRCP (if needed). Patients underwent 3 monthly liver function test and ultrasound and if needed MRCP.

If IHSs were diagnosed during follow-up, small jejunotomy incision in the Roux limb which was easily identified with a mini-laparotomy and allowed introduction of the cystoscope for the same procedure to be followed.

RESULTS

A total of 29 cases of CDC were seen and operated during the study. Six cases had a per-operative diagnosis of IHSs on ultrasound/MRCP. One case presented 3 years after R-en-Y HJ with IHSs. Mean age was 3.85 years (range: 1–14 years). The demographic details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic details

| Sex | Age (years) | CDC type | Jaundice | Cholangitis | Cirrhosis | PHT | IHBD stenosis | Clearance: I/FL | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1 | Type I | - | + | + | - | + | I | - |

| Male | 3 | Type I | - | - | - | - | - | I + FL | - |

| Female | 2.5 | Type I | - | - | - | - | - | I | - |

| Male | 1.5 | Type I | - | - | - | - | - | I + FL | - |

| Male | 2 | Type IVa | + | + | + | + | - | I + FL | + (sludge) |

| Male | 3 | Type I | - | - | - | - | - | I + FL | - |

| Female | 14 | Type I IHSs diagnosed 3 years post-operative | + | + | + | - | - | I + FL | - |

CDC: Choledochal cyst, PHT: Portal hypertension, IHBD: Intrahepatic bile duct, I: Irrigation, FL: Forceps lithotomy, IHSs: Intrahepatic stones, -: Absent, +: Present

The most common variant of CDC found in the study was Type 1 (6 cases). Two cases presented with jaundice, three with cholangitis and cirrhosis and one with portal hypertension and intrahepatic duct stenosis [Table 1]. The patient with IHBD stenosis was dilated with Seldinger technique successfully. As there was a good visualisation of intrahepatic ducts, per-operative intrahepatic cholangiogram was not done. Post-operative recovery in all patients was satisfactory with no complications. The follow-up ranged from 1 to 3 years. One case (Case 5) had recurrence of sludge identified on ultrasound and MRCP on follow-up and was treated with choleretic and cholagogue successfully. Recurrence of stones or stricture was not seen during the available follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The management of IHSs associated with CDC is challenging enough; however, the management of IHSs diagnosed after CDC surgery is even more demanding and requires expertise and high-price equipment which are often not available in resource-constrained settings.[3,4] In the present study, the incidence of IHS at the presentation of CDC was 20.68% [Table 1], which is similar to that reported in literature.[2] The reported incidence of post-operative IHSs varies between 2.7% and 10.7%, and their formation has been reported to occur between 3 and 20 years after CDC excision.[5,6,7] Cause of post-operative IHSs is usually missed/residual debris/stones, missed IHBD stenosis, biliary stasis due to stricture of the hepaticoenterostomy anastomosis or congenitally dilated IHBD.

Advanced and expensive imaging procedures, such as virtual endoscopy and per-operative cholangioscopy, are recommended to identify IHSs and IHBD stenosis associated with CDC, so their simultaneous management can be done.[8,9,10] Even though R-en-Y HJ is considered as the gold standard for reconstruction after CDC excision, recent publications have rekindled the popularity of hepaticoduodenostomy (HD) over R-en-Y HJ.[11] An obvious advantage of HD over R-en-Y HJ is easy endoscopic access to the anastomosis, ease of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, access to a non-dilated system for retrieval of recurrent stones and dilatation of IHBD stenosis, as and when required.[4,12] Other therapeutic modalities for post-operative IHSs include extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy, double-balloon endoscopy and rarely revision hepaticoenterostomy and even liver resection.[5,6,7,13,14,15]

Our use of paediatric size cystoscope for routine per-operative ‘pre-emptive’ cholangioscopy allows for IHBD debris identification plus its clearance, IHSs identification plus its clearance and IHBD stenosis identification plus its dilatation. Intraoperative cholangioscopy using a paediatric cystoscope has been reported for irrigating and clearing IHBD debris during CDC surgery;[16,17] however, we have extended its use to identify/manage stones and stenosis. Such an innovative use exemplifies the multifarious application of an instrument.[18] Easy availability of this modality and its usefulness in identifying/clearing the sludge and stones has now changed our unit policy to use it as a pre-emptive procedure in all cases of CDC during surgery.

CONCLUSION

Per-operative rigid cholangioscopy using paediatric cystoscope during CDC surgery to clear debris, identify/clear stones and dilate stenosis has many advantages: it can be performed easily in a resource-constrained setting as it does not require expensive instrumentation or extraordinary expertise.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chijiiwa K, Koga A. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of patients with choledochal cysts. Am J Surg. 1993;165:238–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohtsuka H, Fukase K, Yoshida H, Motoi F, Hayashi H, Morikawa T, et al. Long-term outcomes after extrahepatic excision of congenital choladocal cysts: 30 years of experience at a single center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamataka A, Ohshiro K, Okada Y, Hosoda Y, Fujiwara T, Kohno S, et al. Complications after cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy for choledochal cysts and their surgical management in children versus adults. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ono S, Maeda K, Baba K, Usui Y, Tsuji Y, Yano T, et al. The efficacy of double-balloon enteroscopy for intrahepatic bile duct stones after roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for choledochal cysts. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:1103–7. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ando H, Kaneko K, Itou H. Complication after cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy for choledochal cysts. Jpn J Pediatr Surg. 1998;30:392–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizote H, Maeda Y, Tanigawa K. Late complication of excision procedure for congenital cyst. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1997;20:1223–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komi N, Takehara H, Kunitomo K, Miyoshi Y, Yagi T. Does the type of anomalous arrangement of pancreaticobiliary ducts influence the surgery and prognosis of choledochal cyst? J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:728–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saing H, Chan JK, Lam WW, Chan KL. Virtual intraluminal endoscopy: A new method for evaluation and management of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1686–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono Y, Kaneko K, Ogura Y, Sumida W, Tainaka T, Seo T, et al. Endoscopic resection of intrahepatic septal stenosis: Minimally invasive approach to manage hepatolithiasis after choledochal cyst excision. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:939–41. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1756-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Okada Y, Yanai T, Lane GJ, et al. Forme fruste choledochal cyst: Long-term follow-up with special reference to surgical technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1833–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santore MT, Behar BJ, Blinman TA, Doolin EJ, Hedrick HL, Mattei P, et al. Hepaticoduodenostomy vs.hepaticojejunostomy for reconstruction after resection of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes TL, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with roux-en-Y anatomy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Şenyüz OF, Gülşen F, Gökhan O, Emre Ş, Eroǧlu E. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy on intrahepatic biliary calculi developing after choledochal cyst surgery: A case report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:274–6. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li SQ, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Hua YP, Lv MD, Fu SJ, et al. Outcomes of liver resection for intrahepatic stones: A comparative study of unilateral versus bilateral disease. Ann Surg. 2012;255:946–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824dedc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuhaus H, Zillinger C, Born P, Ott R, Allescher H, Rösch T, et al. Randomized study of intracorporeal laser lithotripsy versus extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:327–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Yanai T, Lane GJ, Miyano T, et al. Massive debris in the intrahepatic bile ducts in choledochal cyst: Possible cause of postoperative stone formation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:67–9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-003-1086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi T, Shimotakahara A, Okazaki T, Koga H, Miyano G, Lane GJ, et al. Intraoperative endoscopy during choledochal cyst excision: Extended long-term follow-up compared with recent cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:379–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettorini BL, Tamburrini G. Two hundred years of endoscopic surgery: From Philipp Bozzini's cystoscope to paediatric endoscopic neurosurgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:723–4. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]