Abstract

Background:

Recently, there have been several reports on minimally-invasive surgery for extended pancreatectomy (MIEP) in the literature. However, to date, only a limited number of studies reporting on the outcomes of MIEP have been published. In the present study, we report our initial experience with MIEP defined according to the latest the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISPGS) guidelines.

Methods:

Over a 14-month period, a total of 6 consecutive MIEP performed by a single surgeon at a tertiary institution were identified from a prospectively maintained surgical database. EP was defined as per the 2014 ISPGS consensus. Hybrid pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) was defined as when the entire resection was completed through minimally-invasive surgery, and the reconstruction was performed open through a mini-laparotomy incision.

Results:

Six cases were performed including 2 robotic extended subtotal pancreatosplenectomies with gastric resection, 1 laparoscopic-assisted (hybrid) extended PD with superior mesenteric vein wedge resection, 2 robotic-assisted (hybrid) PD with portal vein resection (1 interposition Polytetrafluoroethylene graft reconstruction and 1 wedge resection) and 1 totally robotic PD with wedge resection of portal vein. Median estimated blood loss was 400 (250–1500) ml and median operative time was 713 (400-930) min. Median post-operative stay was 9 (6–36) days. There was 1 major morbidity (Grade 3b) in a patient who developed early post-operative intestinal obstruction secondary to port site herniation necessitating repeat laparoscopic surgery. There were no open conversions and no in-hospital mortalities.

Conclusion:

Based on our initial experience, MIEP although technically challenging and associated with long operative times, is feasible and safe in highly selected cases.

Keywords: Extended pancreatectomy, laparoscopic, minimally-invasive pancreatectomy, robotic, vascular resection

INTRODUCTION

Today, pancreatectomies remain one of the most highly complex surgical procedures in the abdomen and despite advances in surgical technique and perioperative care, are still associated with a high morbidity rate.[1,2] Although both the first case of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy (LPD) and the first case of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (DP) were described back in 1994 by Gagner and Pomp[3] and Cuschieri,[4] respectively, it was not until the past decade that Minimally-Invasive Surgery (MIS) for Pancreatectomies (MISP) started to gain increasing focus and attention.[5] MISP especially LPD have been deemed to be highly technically demanding and associated with a steep learning curve. Reports even from high volume expert centres have demonstrated high conversion rates[6] and increased morbidity[7] compared to the open approach during the initial learning phase. However, with the advent of robotic technology, several authors have proposed that its attendant advantages such as increased dexterity and improved three-dimensional (3D) visualisation can allow surgeons to perform MISP with a shorter learning curve and decreased conversion rates.[8,9,10] Since then, numerous studies have demonstrated MIS to be safe for both DP[11,12,13] and PD,[14] with the MIS approach resulting in decreased blood loss and shorter post-operative stay yet still having similar post-operative morbidity and oncologic outcomes as their open counterpart.[5,11,12,15,16]

With advancements in surgical techniques, technology and perioperative care, extended resections for locally advanced pancreatic malignancies, many of which would have been previously deemed unresectable due to extensive involvement of surrounding structures, are increasingly performed especially in expert tertiary centres.[17] This trend was recognised by the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISPGS), which published a consensus statement on the definition of extended pancreatectomy (EP) in 2014.[18] More recently, several surgeons are now pushing the MISP envelope further by attempting to perform these extended resections through the MIS approach. To date, only a limited number of studies reporting on the outcomes of MIS for extended pancreatectomies (MIEP) have been published.[19,20,21] In the present study, we report our initial experience with MIEP according to the ISPGS guidelines, with the aim of determining its feasibility and safety.

METHODS

Over a 14-month from 2016 to 2017, six consecutive patients who underwent MIEP at a tertiary institution by a single surgeon (Goh BK) were identified from a prospectively maintained surgical database. Before performing the first minimally-invasive extended PD, the surgeon had experience with over 150 laparoscopic/robotic hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) procedures including 30 pancreatectomies since 2012. He also had extensive experience with open surgery having performed over 1000 major HPB and transplant operations since 2007. The choice between the open, laparoscopic or robotic approaches was made after a thorough discussion between the surgeon and patient. In general, the robotic approach was preferred by the surgeon for these complicated operations, but the cost was a major factor in the patient's final decision as patients had to pay an additional USD 5000 for robotic-assisted procedures.

MIEP was defined as either the laparoscopic, laparoscopic-assisted or robotic-assisted approach, and EP was defined in accordance with the 2014 ISPGS guidelines.[18] In general, any PD, DP or total pancreatectomy with adjacent organ resection such as the stomach, colon or vascular resection due to local tumour involvement was considered an EP.[18] Clinicopathological data including patient demographics and relevant pre-, intra-operative and post-operative outcomes were subsequently obtained retrospectively from the patients’ clinical, radiological and pathological records. Clinical data were collected from a prospective computerised clinical database (Sunrise Clinical Manager version 5.8, Eclipsys Corporation, Atlanta, Georgia) and patient's clinical charts while operative data were obtained from another prospective computerised database (OTM 10, IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). The study was approved by our institution's centralised Institution Review Board. Post-operative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo grading system[22] and recorded throughout the post-operative stay. Post-operative pancreatic fistula was defined and graded according to the latest International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula system (ISGPF). This was defined as any amount of drain fluid with an amylase content more than three times the upper normal limit of serum amylase or >300 IU/L on or after the 3rd post-operative day.[23] Purely biochemical Grade A pancreatic fistulas were not considered a fistula according to the latest ISGPF system.

Operative procedure

In all cases, dissection of the tumour and vasculature was performed entirely through the MIS approach. Owing to the complexity of reconstruction in PD, 3 PDs in this series were performed through the hybrid approach whereby the resection was completed entirely through MIS approach, but an open reconstruction was performed through a 6–8 cm upper midline mini-laparotomy incision. The size of the incision required varied with the body habitus of the patient. The da Vinci Si Surgical System (Intuitive, Sunnyvale, California) was used in all robotic cases.

Robotic extended DP was performed using a 12-mm subumbilical camera port, three 8-mm ports for the robotic arms (1 epigastric, 1 right hypochondrium and 1 left hypochondrium) and a single assistant 12 mm port in the left paraumbilical region. Resection proceeded from medial to lateral as previously described.[10,24]

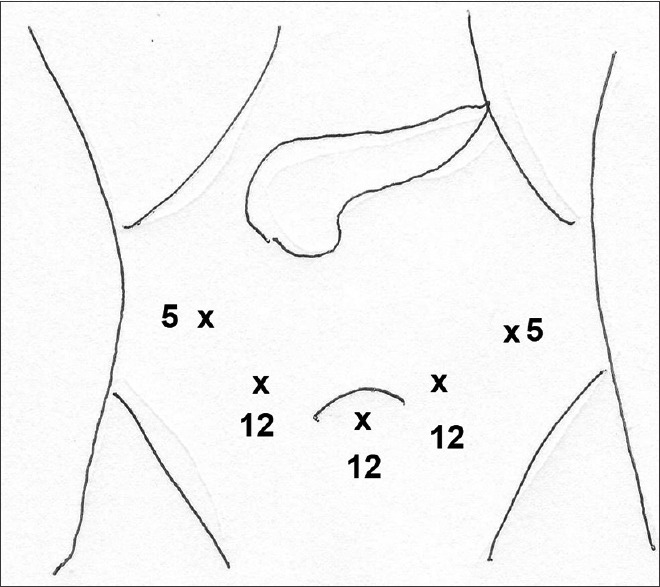

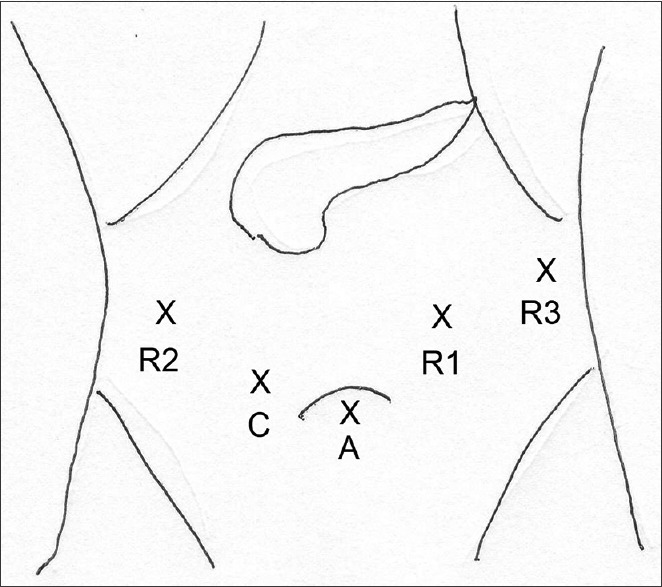

Laparoscopic (hybrid) PD was performed using five ports (three 12 mm in the subumbilical, right iliac fossa, left paraumbilical) and two 5 mm in the left and right flank arranged in a ‘smiley face configuration’ [Figure 1]. For robotic (hybrid) PD, the 12 mm subumbilical port was used as an assistant port and 12 mm right iliac fossa port was used as the camera port. One 8 mm robotic port was placed in the right hypochondrium and two 8 mm robotic ports were placed in the left hypochondrium [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Port placement for laparoscopic PD

Figure 2.

Port placement for robotic PD

The operation generally proceeded as follows. First, the hepatic flexure was mobilised, and subsequently, the porta hepatis was dissected. The lesser sac was entered through the gastrocolic omentum and the gastrocolic trunk divided. The inferior border of the pancreas was dissected, and the retropancreatic portal tunnel was created. Complete kocherisation of the duodenum was then performed, and the duodenojejunal flexure was mobilised and divided in the supracolic compartment. The pancreatic neck and bile duct were divided, and finally, the uncinate process was dissected off the superior mesenteric vein and artery. After the resection was completed, reconstruction was performed through an 8 cm minilaparotomy. The jejunal loop was pulled through the native duodenal tunnel and an iso-loop reconstruction with an end-to-side duct-to-mucosa Blumgart-style pancreatojejunostomy, end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy and end-to-side gastrojejunostomy was performed.

RESULTS

The details of the six patients are summarised in Table 1. In all six cases, the possible need for an EP was considered preoperatively based on the pre-operative cross-sectional imaging findings. Median estimated blood loss was 400 (range, 250–1500) ml and median operative time was 713 (range, 400-930) min. Median post-operative stay was 9 (6–36) days. In all six cases, resection was completed without any premature open conversions, and there were no 90-day/in-hospital mortalities. There were no clinically relevant fistulas. Post-operative morbidity occurred in three patients including one patient with chyle leak requiring total parenteral nutrition, one patient with readmitted with urinary tract infection with sepsis and 1 who had a Grade 3b port-site hernia requiring reoperation.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinicopathological features and perioperative outcomes of the 6 patients who underwent Minimally-Invasive Surgery for Extended Pancreatectomy

| Patient | Age, year/sex | Surgery | MIS approach | Type of additional resection | Operative time, min | EBL, ml | Blood transfusion | LOS, days | Complication | Clavien-Dindo grade | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 52/male | PD | Lap (hybrid) | SMV, wedge | 595 | 400 | Nil | 6 | Nil | Nil | T3N1 adenoca, 3 cm clear |

| Case 2 | 75/female | DP | Robotic | Stomach | 775 | 800 | Yes | 8 | Nil | Nil | T3N1 adenosquamous ca, 5.5cm, clear |

| Case 3 | 67/female | DP | Robotic | Stomach | 400 | 300 | Nil | 10 | Reoperation for port site hernia with small bowel obstruction | IIIb | Mucinous cystic neoplasm with associated adenoca, T2N1 13.8cm, clear |

| Case 4 | 78/female | PD | Robotic (hybrid) | SMV with PTFE graft reconstruction | 930 | 1500 | Yes | 8 | Nil | Nil | T3N1 adenoca, 1.5 cm |

| Case 5 | 53/male | PD | Robotic (hybrid) | PV, wedge | 725 | 400 | Nil | 36 | Chyle leak requiring TPN | 2 | T3N1 adenoca, 2.3 cm |

| Case 6 | 67/male | PD | Robotic | PV, wedge | 700 | 250 | Nil | 10 | Urinary tract infection | 2 | T3 N1 adenoca, 2.6 cm |

DP: Distal Pancreatectomy, PD: Pancreatoduodenectomy, PV: Portal vein, PTFE: Polytrafluoroethylene, SMV: Superior mesenteric vein, TPN: Total parenteral nutrition, MIS: Minimally-invasive surgery, EBL: Estimated blood loss, LOS: Length-of-stay

DISCUSSION

MISP has been increasingly adopted over the past decade, and numerous studies have demonstrated its advantages over the open approach.[5,11,12,15,16,25,26,27] Despite longer operative times, the MISP confers the usual benefits associated with MIS such as shorter recovery, decreased blood loss, better cosmetic results and early access to adjuvant therapy.[25] Several meta-analyses have shown minimally-invasive PD (MIPD) to be significantly associated with decreased blood loss,[26,27] shorter post-operative stay,[26,27] fewer wound infections,[26] improved lymph node harvest,[26] lower likelihood of R1 resections[26] and less delayed gastric emptying.[27] In the case of DP, numerous large series have also shown similar benefits such as lower blood loss and blood transfusion rates, shorter hospital stays, higher splenic preservations and fewer clinically significant pancreatic fistula in the laparoscopic DP group.[12]

Despite these advantages, the adoption of MISP especially MIPD remains confined to a relatively small number of surgeons worldwide due to its technical difficulty. This is inexorably due to the complex dissection and reconstruction required for successful completion of MIPD.[28,29] The robotic platform presents a valuable option for a surgeon keen to perform MIPD. Despite its prohibitive cost and lack of haptic feedback, the robot provides advantages of improved 3D visualisation, greater instrument range of motion and elimination of tremors allowing for better fine motor movement compared to laparoscopy.[28,30,31] Based on our preliminary experience with MIEP whereby 5 of the 6 procedures in the present study were performed through robotic assistance, we found that the robotic approach was advantageous over conventional laparoscopy for these complex resections. The stability and increased dexterity of the robotic platform enabled fine precise suturing in tight places which was especially useful to control bleeding from torn branches of the portal/superior mesenteric vein. In recent times, several authors have also demonstrated that robotic pancreatectomies were associated with a similar safety profile as open resections albeit requiring longer operating times.[8,32,33,34] We only attempted 1 reconstruction through the minimally invasive approach (after five cases) in this study as this series represented our preliminary experience with MIEP and we felt that the additional operating time associated with the reconstruction could potentially be detrimental to patient outcomes.

Today, EP is routinely performed for locally advanced pancreatic and periampullary tumours, with the involvement of surrounding structures in specialised tertiary centres.[18] Extended pancreatectomies are highly complex technically demanding procedures associated with a significantly higher morbidity and mortality rate compared to standard resections.[35] Not surprisingly, in the vast majority of studies reporting on EP, the procedure was performed through the open approach,[35,36] with only limited reports of MIEP in the literature to date.[19,20,21]

In the first series of MIEP, Giulianotti et al. analysed five patients who underwent robotic pancreatectomy with MVR, of which two were DP with celiac trunk resection, two were PD with PV resection and one was DP with PV resection. Although mean post-operative stay was 11 ± 2 days and mean blood loss was 200 ± 61 ml, three patients sustained post-operative morbidity, with one requiring repeat surgery for duodenal ulcer perforation.[19] Kendrick and Sclabas reported comparable perioperative outcomes in his study of 11 patients at the Mayo Clinic who underwent laparoscopic PD with vascular resection.[20] Of the 10 who had the malignant disease in his series, 9 (90%) had R0 resection. The authors also proposed that the laparoscopic approach could provide additional benefits such as superior views and magnification and decreased low-pressure bleeding from positive intra-abdominal pressure. The same group subsequently published the largest series to date on MIEP of which they compared 31 MIPD with 58 Open PD with major venous resection and found significantly shorter hospital stay in favour of the MIPD group with no difference in the morbidity or mortality rates.[21] In addition, there was no difference between the overall survival rates of both groups after a median follow-up period of 15.2 months in the MIPD group and 14.8 months in the open group.[21] Interestingly, a significantly higher rate of R0 resection was obtained in the MIPD group, which the authors postulated could be due to the advantages of laparoscopy as elucidated in their previous study.[20] Table 2 summarises selected studies on MIEP previously reported in the literature.

Table 2.

Summary of selected studies reporting outcomes of minimally-invasive surgery for extended pancreatectomy

| Author, year | Center/country | Number of MIEP patients, n | Procedure Type | Organs resected | Median operative time | Median EBL, ml | Conversion | Median LOS, days | Morbidity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giulianotti et al., 2011[19] | Illinois, USA | 5 | 3 RDP, 2 RPD | 2 Celiac trunk, 3 PV | 400 (310-460) | 200 (150-300) | 0/5 | 11±2* | 1 perforated duodenal ulcer, 1 grade A pancreatic fistula, 1 intraabdominal collection | |

| Kendrick and Sclabas 2011[20] | Mayo Clinic, USA | 11 | 9 TLPD, 2 RLPD | 6 SMV, 3 PV, 2 both SMV and PV | 413 (301-666) | 500 (75-2800) | 1/11 | 7 (4-35) | 6 pancreatic leak, 3 post-operative anemia/bleeding, 2 arrhythmia, 1 transient renal failure, 1 delayed gastric emptying | 9/10 R0 resection, 1 chronic pancreatitis |

| Croome et al. 2015[21] | Mayo Clinic, USA | 31 | 29 TLPD, 2 RLPD | 10 PV, 11 SMV, 1 Arterial, 9 Multiple | 465±86* | 841.8±994.8* | 4/31 | 6 (4-118) | 11/31 any complication; 2 grade 3 and above | 29/31 R0 resection. 1/31 (3.2%) 30-day mortality rate |

*Mean values. EBL: Estimated blood loss, LOS: Length-of-stay, RDP: Robotic-assisted Distal Pancreatectomy, RPD: Robotic-assisted Pancreatoduodenectomy, RLPD: Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Pancreatoduodenectomy, USA: United States of America, MIEP: Minimally-Invasive Surgery for Extended Pancreatectomy, PV: Portal vein

Our initial experience with MIEP seems to support the findings in the literature that MIEP is feasible and safe. To the best of our knowledge, this series is the first to examine MIEP using the ISPGS definition and as such analyses not only vascular resection but also concomitant organ resection. In this study, only one patient experienced a major complication (>Grade 2) which was an early postoperative small bowel obstruction from port-site herniation requiring laparoscopic reduction and port-site repair. There were no clinically significant postoperative pancreatic fistulae or perioperative bleeding requiring re-intervention or open conversion. In three patients who underwent MIPD, we opted to perform open reconstruction as this study represented our initial experience with MIEP. It has previously been shown that the hybrid approach for PD is a safe ‘in between’ approach for surgeons first embarking on MISP.[37,38] Although the procedures in this study were associated with relatively long operative times, this did not seem to have a major impact on the patients’ post-operative outcomes. It is likely that the operative times would reduce as we gained further experience and progress along the learning curve.[9]

CONCLUSION

Based on our initial experience, MISEP although technically challenging and associated with long operative times, is feasible and safe in highly selected cases. Prospective comparative large-scale studies with a long-term follow-up should be performed to determine its superiority over the open approach.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Goh has received travel grants and honoraria from Transmedic the local distributor for the Da Vinci Robotic platform.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Cheow PC, Ong HS, Chan WH, et al. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: A 21-year experience at a single institution. Arch Surg. 2008;143:956–65. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00642443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39:178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boggi U, Amorese G, Vistoli F, Caniglia F, De Lio N, Perrone V, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic literature review. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:9–23. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3670-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SY, Allen PJ, Sadot E, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: A single institution's experience in open, laparoscopic, and robotic approaches. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dokmak S, Ftériche FS, Aussilhou B, Bensafta Y, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy should not be routine for resection of periampullary tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:831–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zureikat AH, Moser AJ, Boone BA, Bartlett DL, Zenati M, Zeh HJ 3rd, et al. 250 robotic pancreatic resections: Safety and feasibility. Ann Surg. 2013;258:554–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a4e87c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daouadi M, Zureikat AH, Zenati MS, Choudry H, Tsung A, Bartlett DL, et al. Robot-assisted minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy is superior to the laparoscopic technique. Ann Surg. 2013;257:128–32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825fff08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh BK, Chan CY, Soh HL, Lee SY, Cheow PC, Chow PK, et al. A comparison between robotic-assisted laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy? Int J Med Robot. 2017:13. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1733. Doi:10.1002/rcs.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci C, Casadei R, Taffurelli G, Toscano F, Pacilio CA, Bogoni S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:770–81. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2721-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura M, Wakabayashi G, Miyasaka Y, Tanaka M, Morikawa T, Unno M, et al. Multicenter comparative study of laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy using propensity score-matching. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:731–6. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrabi A, Hafezi M, Arvin J, Esmaeilzadeh M, Garoussi C, Emami G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy for benign and malignant lesions of the pancreas: It's time to randomize. Surgery. 2015;157:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin SH, Kim YJ, Song KB, Kim SR, Hwang DW, Lee JH, et al. Totally laparoscopic or robot-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open surgery for periampullary neoplasms: Separate systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3459–74. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marangos IP, Buanes T, Røsok BI, Kazaryan AM, Rosseland AR, Grzyb K, et al. Laparoscopic resection of exocrine carcinoma in central and distal pancreas results in a high rate of radical resections and long postoperative survival. Surgery. 2012;151:717–23. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kooby DA, Hawkins WG, Schmidt CM, Weber SM, Bentrem DJ, Gillespie TW, et al. A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: Is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:779. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bockhorn M, Uzunoglu FG, Adham M, Imrie C, Milicevic M, Sandberg AA, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A consensus statement by the international study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2014;155:977–88. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartwig W, Vollmer CM, Fingerhut A, Yeo CJ, Neoptolemos JP, Adham M, et al. Extended pancreatectomy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Definition and consensus of the international study group for pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2014;156:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giulianotti PC, Addeo P, Buchs NC, Ayloo SM, Bianco FM. Robotic extended pancreatectomy with vascular resection for locally advanced pancreatic tumors. Pancreas. 2011;40:1264–70. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318220e3a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendrick ML, Sclabas GM. Major venous resection during total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:454–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Truty MJ, Nagorney DM, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with major vascular resection: A comparison of laparoscopic versus open approaches. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:189–94. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, et al. The 2016 update of the international study group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 2017;161:584–91. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goh BK, Wong JS, Chan CY, Cheow PC, Ooi LL, Chung AY, et al. First experience with robotic spleen-saving, vessel-preserving distal pancreatectomy in Singapore: A report of three consecutive cases. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:464–9. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bencini L, Annecchiarico M, Farsi M, Bartolini I, Mirasolo V, Guerra F, et al. Minimally invasive surgical approach to pancreatic malignancies. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7:411–21. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i12.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correa-Gallego C, Dinkelspiel HE, Sulimanoff I, Fisher S, Viñuela EF, Kingham TP, et al. Minimally-invasive vs.open pancreaticoduodenectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Steen MW, Gerhards MF, Dijkgraaf MG, Busch OR, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative cohort and registry studies. Ann Surg. 2016;264:257–67. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendrick ML, Cusati D. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: Feasibility and outcome in an early experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145:19–23. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, Büchler MW. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7:99–108. doi: 10.1080/13651820510028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendrick ML. Laparoscopic and robotic resection for pancreatic cancer. Cancer J. 2012;18:571–6. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31827b8f86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talamini MA, Chapman S, Horgan S, Melvin WS Academic Robotics Group. A prospective analysis of 211 robotic-assisted surgical procedures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1521–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boggi U, Napoli N, Costa F, Kauffmann EF, Menonna F, Iacopi S, et al. Robotic-assisted pancreatic resections. World J Surg. 2016;40:2497–506. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giulianotti PC, Sbrana F, Bianco FM, Elli EF, Shah G, Addeo P, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: Single-surgeon experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1646–57. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou JY, Xin C, Mou YP, Xu XW, Zhang MZ, Zhou YC, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: A Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartwig W, Gluth A, Hinz U, Koliogiannis D, Strobel O, Hackert T, et al. Outcomes after extended pancreatectomy in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103:1683–94. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low TY, Koh YX, Teo JY, Goh BK. Short-term outcomes of extended pancreatectomy: A Single-surgeon experience. Gastrointest Tumors. 2018;4:72–83. doi: 10.1159/000484523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speicher PJ, Nussbaum DP, White RR, Zani S, Mosca PJ, Blazer DG, 3rd, et al. Defining the learning curve for team-based laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4014–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang S, Jayaraman S. Getting started with minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: Is it worth it? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:712–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]