Abstract

BACKGROUND

Serum N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is considered a marker that is expressed in response to myocardial strain and possibly fibrosis. However, the relationship to myocardial fibrosis in a community-based population is unknown.

OBJECTIVES

The authors evaluated the relationship between cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) measures of fibrosis and NT-proBNP levels in the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study.

METHODS

A total of 1,334 participants (52% white, 23% black, 11% Chinese, 14% Hispanic, and 52% men with a mean age of 67.6 years) at 6 sites had both serum NT-proBNP measurements and CMR with T1 mapping of indices of fibrosis at 1.5 T. Univariate and multivariable regression analyses adjusting for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and left ventricular (LV) mass were performed to examine the association of log NT-proBNP with CMR T1 mapping indices.

RESULTS

In the fully adjusted model, each 1-SD increment (0.44 pg/ml) of log NT-proBNP was associated with a0.62% increment in extracellular volume fraction (p < 0.001), 0.011 increment in partition coefficient (p < 0.001), and 4.7-ms increment in native T1 (p = 0.001). Results remained unchanged after excluding individuals with clinical cardiovascular disease or late gadolinium enhancement (n = 167), and after replacing LV mass by LV end-diastolic volume in the regression models.

CONCLUSIONS

Elevated NT-proBNP is related to subclinical fibrosis in a community-based setting. (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]; NCT00005487) (J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:3102–9) Published by Elsevier on behalf of the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

Keywords: ECV, MR imaging, NT-proBNP, T1 mapping

Myocardial fibrosis is a common histological feature of the failing heart. Myocardial fibrosis occurs either as a reparative process after acute cardiac injury or as a nonspecific response to chronic conditions, including elevated myocardial strain and pressure overload. The identification of myocardial fibrosis by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) provides a highly sensitive method to evaluate myocardial scar with prognostic significance (1,2). In the setting of heart failure, fibrosis may also be diffuse throughout the myocardium (3). Diffuse fibrosis may be identified in vivo noninvasively using CMR T1 mapping methods (3–5).

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is synthesized in the myocardium as a pre-hormone (pro-BNP) and enzymatically cleaved into biologically active (BNP) and inactive (N-terminal pro-BNP [NT-proBNP]) fragments upon release into the circulation. Both BNP and NT-proBNP are well-described markers of congestive heart failure (6–8). NT-proBNP also predicts new cardiac events (9) as well as subclinical heart and vessel disease (10). NT-proBNP and BNP have been correlated with left ventricular (LV) wall stress (11) and myocardial scar size (12). A murine study showed that fibrosis determines cardiac BNP expression (13). Diffuse fibrosis assessed by CMR T1 mapping techniques were associated with elevated serum BNP in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (14) and systemic hypertension (15). However, the relationship between NT-proBNP and diffuse fibrosis in a community-based population is unknown.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between serum NT-proBNP levels and diffuse myocardial fibrosis as detected by CMR in a community-based study. These findings may help in understanding the association of increased neuro-hormonal levels on diffuse fibrosis and bridge the gap between the known prognostic implications of certain serum biomarkers and specific clinical phenotypes.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN.

In 2000, the MESA (Multi-Ethnic-Study of Atherosclerosis) study began with the enrollment of 6,814 individuals, including individuals of white, African-American (black), Chinese, and Hispanic ethnicity. The baseline cohort included men and women with no clinical history of cardiovascular disease and between 45 to 84 years of age recruited from 6 field centers (Baltimore City and Baltimore County, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Los Angeles County, California; Northern Manhattan and the Bronx, New York; and St. Paul, Minnesota). In 2010, MESA participants were examined for the 10-year follow-up (fifth examination). A total of 3,012 participants had CMR examinations, among which 1,334 participants (44%) consented to receive a CMR contrast agent and had T1 mapping. All participants underwent plasma NT-proBNP measurements in the fifth examination. Only participants with both CMR T1 mapping and NT-proBNP measurements were included in the final analyses. By the time of the follow-up exam, 80 participants (6%) had experienced an incident cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, angina, congestive heart failure, and stroke). One hundred seven participants (8%) had findings of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in the CMR studies of the fifth examination. Altogether, 167 participants had either a cardiovascular event or LGE. Institutional review boards at each of the 6 field centers approved the study protocols, and all attendees at the examinations provided written informed consent. Details of the MESA study design, NT-proBNP, and risk factor measurements have been described elsewhere (16,17).

CMR MEASURES.

1.5-T whole-body imagers were used in all CMR studies. LV cine imaging was performed using steady-state free precession sequences. LV structural and functional measures included LV mass, end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), mass-to-volume ratio, stroke volume, and ejection fraction. Myocardial T1 maps and CMR methods were described previously (18). Briefly, T1 mapping indices including pre-(native) and post-contrast T1 times at 12 and 25 min, partition coefficient (l), and extracellular volume fraction (ECV) (ECV = 100 × λ × [1 – hematocrit]) were assessed using a single–breath-hold modified Look-Locker inversion recovery sequence.

In the current study, hematocrit was measured in only 608 participants (45.5%) with CMR T1 mapping. ECV was calculated in these participants. Using the same methodology described in Treibel et al. (19), we performed an errors-in-variables linear regression between hematocrit as the dependent variable and pre-contrast T1 of the blood pool as the independent variable to model the synthetic hematocrit values as HCTsyn = 726.19 × (1/T1 precontrast blood) – 0.07. The synthetic ECV and real ECV were highly correlated (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.89) and the difference between the two was not significant (mean difference: 0.017 ± 1.435%; p = 0.75). These synthetic hematocrit values were then used for ECV calculations for those without hematocrit in the study.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical variables as percentages. Linear regression was used to determine the relationship between log10 NT-proBNP and each T1 index. Regression models were examined as follows: unadjusted models were fit, followed by models minimally adjusted for age, sex, and race, and finally fully adjusted models including minimal + smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, low-density lipo-protein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, hypertension (including those with antihypertensive treatment), diabetes, serum creatinine, statin usage, cardiovascular events or LGE, and LV mass. In secondary analyses, the fully adjusted model was repeated by replacing LV mass with LV EDV. We also repeated the fully adjusted model after excluding individuals with prior cardiovascular events or LGE. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0, IBM, Chicago, Illinois), and significance was declared as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

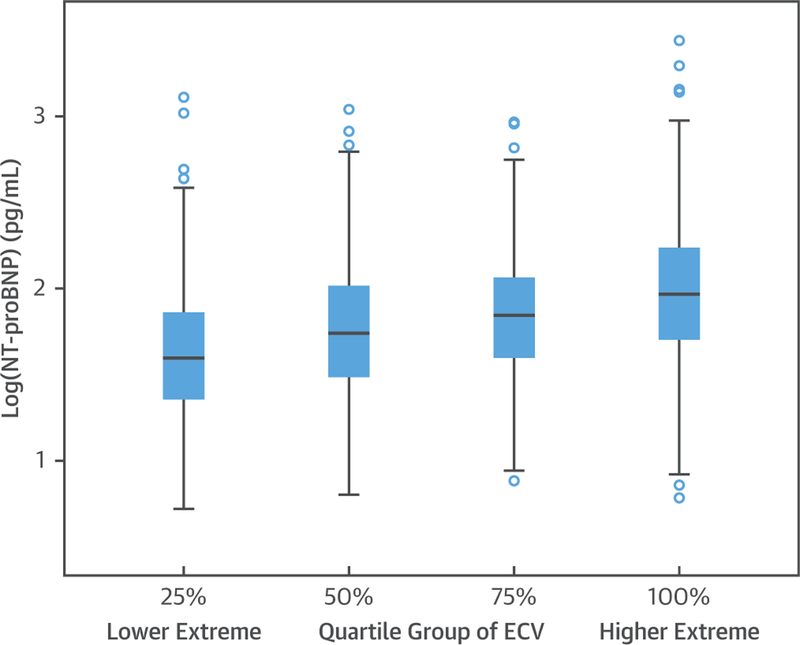

A total of 1,334 participants (52% men, age range 55 to 94 years, mean 67.6 years) had both serum NT-proBNP measurements and CMR T1 mapping quantifications. The study population was 52% white, 11% Chinese, 23% black, and 14% Hispanic ethnicity. One hundred sixty-seven participants (12.5%) who had incident cardiovascular events or LGE were included in the primary analyses. Plasma NT-proBNP levels ranged between 5 to 2,754 pg/ml (interquartile range: 33 to 124 pg/ml) with a median value of 64.9 pg/ml. The mean ECV was within normal limits (25.9 ± 3.0%) as was the native T1 time (977 ± 42.3 ms) (20). Other characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 demonstrates the box plot of log NT-proBNP across quartiles of ECV. When compared with the rest of participants without CMR T1 mapping acquisitions (unpaired Student’s t-test), the participants with T1 mapping were younger (67.6 ± 8.8 years vs. 70.1 ± 9.4 years; p < 0.001), with less hypertension (54% vs. 60%; p < 0.001), and lower log NT-proBNP levels (1.83 ± 0.44 pg/ml vs. 1.93 ± 0.47 pg/ml; p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants in the MESA’s Fifth Examination (N = 1,334)

| Age, yrs | 67.6 ± 8.8 |

| Male | 52 |

| Race White Chinese Black Hispanic |

52 11 23 14 |

| Log NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 1.83 ± 0.44 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 64.9 (33–124) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 5.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 121 ± 19 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 68 ± 10 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 64.1 ± 10.3 |

| Current smoker | 7 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 105.1 ± 31.0 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 54.3 ± 16.0 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 112.0 ± 64.9 |

| Hypertension | 54 |

| Diabetes | 16 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.86 ± 0.19 |

| Statins use | 39 |

| Presence of CVD* or LGE | 167 (12.5) |

| LV EDV index, ml/m2 | 65.5 ± 13.7 |

| LV ESV index, ml/m2 | 25.3 ± 8.4 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 65.9 ± 13.0 |

| LV M/V ratio, g/ml | 1.03 ± 0.23 |

| LV stroke volume index, ml/m2 | 40.2 ± 8.4 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 61.7 ± 7.1 |

| Extracellular volume fraction, % | 25.9 ± 3.0 |

| Partition coefficient | 0.45 ± 0.04 |

| Native T1, ms | 977.0 ± 42.3 |

| Post-12-min T1, ms | 456 ± 40 |

| Post-25-min T1, ms | 519 ± 41 |

Values are mean ± SD, %, median (interquartile range), or n (%). LV structure index is by body surface area.

Including myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, angina, congestive heart failure, and stroke.

CVD = cardiovascular disease; EDV = end-diastolic volume; ESV = end-systolic volume; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LV = left ventricular; M/V = mass to end diastolic volume; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide.

FIGURE 1. Box Plot of Log NT-proBNP Across Quartiles of CMR ECV.

Box plot showing the relationship between NT-proBNP and quartile of ECV. CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; ECV = extracellular volume fraction; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic protein.

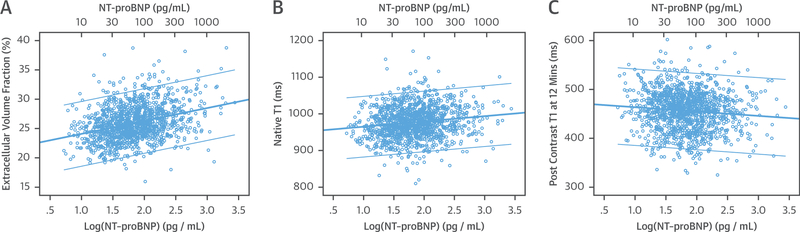

Table 2 shows the relationship of CMR markers of myocardial fibrosis and log NT-proBNP. In the regression analyses, log NT-proBNP was positively associated with all markers in the unadjusted analyses (all p < 0.001). However, the associations only remained significant in ECV (β = 1.4, p < 0.001), partition coefficient (β = 0.024, p < 0.001), and native T1 (β = 10.66, p = 0.001) in the fully adjusted model. Post-T1 times were not associated with NT-proBNP levels after adjustments. The unadjusted associations of ECV, native T1, and post-contrast T1 times at 12 min with log NT-proBNP are presented in Figure 2.

TABLE 2.

The Relationship of LV T1 Indices With Plasma Log NT-proBNP

| Model | ECV (%) | Partition Coefficient | Native T1 (ms) | Post-12-min T1 (ms) | Post-25-min T1 (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | β (SE) | 2.2 (0.177) | 0.025 (0.003) | 14.39 (2.65) | −8.87 (2.5) | −13.38 (2.53) |

|

p Value |

<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Minimally adjusted* | β (SE) | 1.55 (0.195) | 0.023 (0.003) | 10.85 (2.98) | −0.05 (2.64) | −2.81 (2.66) |

|

p Value |

<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.29 | |

| Fully adjusted† | β (SE) | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.024 (0.003) | 10.66 (3.11) | −0.38 (2.59) | −3.004 (2.57) |

|

p Value |

<0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.24 | |

Bold indicates p < 0.05.

Minimally adjusted for age, sex, and race.

Fully adjusted = minimally adjusted þ smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and hypertension (including those with antihypertensive treatment), diabetes, serum creatinine, statins usage, cardiovascular events or LGE, and LV mass.

ECV = extracellular volume fraction; SE = standard error; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

FIGURE 2. The Unadjusted Relationships Between Log NT-proBNP and T1 Indices.

The relationships between log NT-proBNP and myocardial fibrosis assessed by CMR ECV (A), native T1 (B), and post-contrast T1 (C) at 12 min. Unadjusted linear regression demonstrated significant positive correlation between log NT-proBNP and ECV as well as native T1 (p < 0.001). The correlation remained significant after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors. NT-proBNP was negatively related to post contrast T1 in the unadjusted model (p < 0.001) but not after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Table 3 further displays standardized results for the association of ECV, partition coefficient, and native T1 with log NT-proBNP in the fully adjusted model, in which a 1-SD increment of log NT-proBNP(0.44 pg/ml) was associated with increments of0.62% in ECV, 0.011 in partition coefficient, and 4.72 ms in native T1. In the fully adjusted model, results were not substantially changed after excluding individuals with clinical cardiovascular disease or LGE (12.5% of the study population) or replacing LV mass with LV EDV (results not shown). Adjusting further for confounders, including educational level, physical activity, or coronary calcium score, also did not substantially alter the results. ECV appeared strongly associated with log NT-proBNP regardless of the covariates. Using only the ECV with laboratory hematocrit (n = 608, 46%) did not change the results, either. We also performed the fully adjusted analyses stratified by race/ethnicity. Whites and blacks demonstrated similar trends and patterns in the associations between log NT-proBNP and T1 indices as shown in Table 2, but these associations were not statistically significant for individuals of Chinese and Hispanic ethnicity.

TABLE 3.

Cross-Sectional Association Between CMR Markers of Fibrosis and Log NT-proBNP in the Fully Adjusted Model

| Extracellular Volume Fraction, % | Partition Coefficient |

Native T1, ms |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI*) | 0.21 (0.15−0.27) | 0.26 (0.19−0.32) | 0.11 (0.01−0.20) | |

| Increment in CMR marker per 1-SD change in log NT-proBNP (95% Cl)† | 0.62 (0.4−0.72) | 0.011 (0.008−0.013) | 4.7 (0.43−8.5) |

Markers of fibrosis include ECV, partition coefficient, and native T1. Bold indicates p < 0.05.

Standardized coefficient adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, hypertension (including those with antihypertensive treatment), diabetes, serum creatinine, statin usage, cardiovascular events or LGE, and LV mass.

Increment in ECV (%), partition coefficient, or native T1 (ms) per 1-SD increment in log NT-proBNP (1-SD increment = 0.44 pg/ml).

DISCUSSION

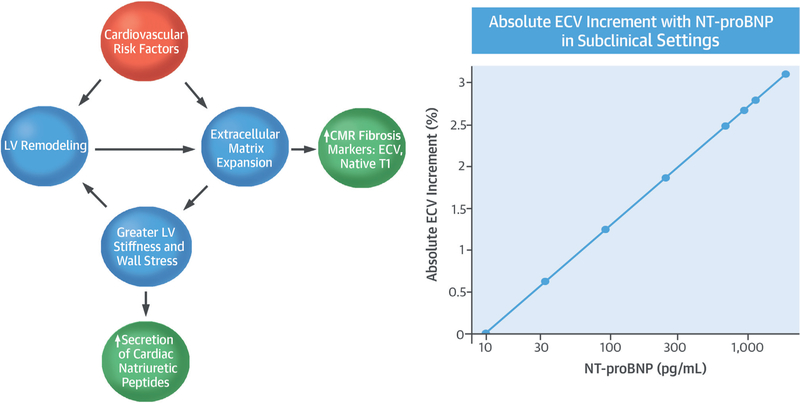

CMR T1 mapping may be used to derive markers that reflect diffuse myocardial fibrosis. CMR is unique in this regard, as there is no other widely accepted method that can noninvasively assess myocardial tissue composition and diffuse fibrosis. NT-proBNP levels are expressed in response to increased myocardial wall stress and have also been linked to myocardial fibrosis in an animal study (13). Prior studies of patients with known cardiovascular disease have shown the utility of both T1 mapping indices and NT-proBNP to determine disease severity (7,8,21–24). However, our results show that even in a community setting of largely asymptomatic individuals, NT-proBNP is associated with myocardial fibrosis detected by CMR. These findings may be relevant to our understanding of the transition from subclinical disease to a clinical disease pheno-type that is ultimately characterized by myocardial stiffening and fibrosis, (e.g., as in diastolic heart failure) (Central Illustration).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Association of NT-proBNP With CMR-Measured ECV.

(Left) Cardiovascular risk factors ultimately result in myocardial remodeling and increased myocardial wall stress. In response, cardiac natriuretic peptides are secreted and are detected in the serum. Myocardial remodeling and wall stress will also result in expansion of the extracellular matrix and collagen deposition. (Right) In the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) population, greater levels of NT-proBNP are associated with greater ECV. Regression estimates based on the fully adjusted models are shown. CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; ECV = extracellular volume fraction; LV = left ventricular; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic protein.

Natriuretic peptides are produced primarily within the heart and released into the circulation in response to increased wall tension (25). Prior MESA studies have shown NT-proBNP as an independent predictor of heart failure (6,22). Reduced myocardial perfusion was also associated with increased NT-proBNP in another MESA study (23). Although the prognostic value of BNP or NT-proBNP in heart failure has been demonstrated, there are only limited data to link higher NT-proBNP levels to reactive collagen deposition before reparative fibrosis (15). Given that ECV, NT-proBNP, and BNP each has predictive power for cardiovascular disease outcomes in patients, there is an unmet need to elucidate the relationship between the imaging phenotype and serum biomarkers. Our results extend the prior observations of NT-proBNP in relationship to cardiovascular events or death in several community studies (21,24) to a subclinical marker of diffuse fibrosis. In the current community-based study, an individual with NT-proBNP of 209 pg/ml would be predicted to have a 2% greater ECV compared with an individual with NT-proBNP of 10 pg/ml. Rommel et al. (26) showed a mean difference of 4% in ECV in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction versus control subjects. This suggests a preclinical phase of diffuse fibrosis may exist in asymptomatic subjects, and supports the concept that even relatively low elevations of NT-proBNP are an indicator of diffuse fibrosis. Furthermore, these data provide an implication to studies describing the role of myocardial fibrosis in the development of heart failure and support biomarkers as predictors of heart failure or adverse cardiovascular events.

Excess deposition of collagen in the extracellular matrix can lead to increased myocardial stiffness and, subsequently, to cardiac hypertrophy and LV dysfunction (27). Increased myocardial scar size was associated with higher BNP in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, and myocardial fibrosis appeared to be related to BNP through the process of ventricular remodeling (12). Understanding the pathogenesis of interstitial fibrosis in the stressed heart and dissecting the mechanisms responsible for adverse cardiac outcomes are crucial to design new strategies for prevention of cardiac failure and myopathy. In an animal model, the change of ECV occurred earlier than myocardial dysfunction in diabetic rabbits (28). It is generally accepted that in the process of the pathological remodeling of cardiomyopathy, progressive accumulation of extracellular matrix components increases cardiac stiffness (29,30). Cardiac natriuretic peptides are secreted in response to elevated pressure load. Structural rearrangement of cardiac chambers follows, and the expansion of the extracellular matrix further augments wall tension, which in turn triggers the production of cardiac natriuretic peptides. Reciprocal interaction of BNP secretion, LV remodeling, and interstitial fibrosis plays a crucial role in heart failure as an irreversible clinical endpoint.

Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship with incident heart failure or coronary heart disease have been reported (31,32). Blacks are at a higher risk for incident heart failure than other ethnic groups, which is mainly attributed to their higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus (31). However, Akwo et al. (33) in the Southern Community Cohort Study found no difference in the heart failure incidence between whites and blacks with similar socioeconomic status. While examining NT-proBNP and T1 indices relationships, we recognized previously that multiple factors influenced CMR-measured T1 indices, including age and sex (18). The MESA study includes participants of 4 races/ethnicities. The aim of our study was to investigate the relationship between T1 mapping indices and NT-proBNP; hence, race/ethnicity was treated as a covariable to increase the statistical power. While examining such relationships independently in each race, the associations between NT-proBNP and T1 indices remained significant in whites and blacks, but most of these associations were not statistically significant in Chinese and Hispanics when adjusted for comorbidities. The weaker associations may be due to smaller sample sizes in these 2 races versus lack of association. Further understanding is needed regarding the interaction of race/ethnicity with diffuse fibrosis and NT-proBNP.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

Because our analysis was cross-sectional, a causal relationship between NT-proBNP and CMR T1 mapping indices cannot be determined. It is not clear whether the elevated ECV is a result of NT-proBNP expression, or the elevated NT-proBNP expression is a result of ECV. CMR T1 mapping indices are not specific for myocardial fibrosis, although fibrosis is by far the most common determinant of altered CMR T1 indices in this community population. Synthetic ECV was used for 54% of the studies without a laboratory hematocrit. LV wall stress was not assessed. Multivariable adjustment was based on traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors that were generally available. Temporal bias and selection bias between baseline (year 2000) and follow-up (year 2010) might have occurred, and those willing to receive a CMR contrast agent may have been systematically healthier than those who were not eligible or declined. A total of 167 subjects had interim clinical cardiovascular disease between the baseline and follow-up year 2010, but the analysis produced similar results with or without those subjects.

CONCLUSIONS

In a large community-based population, we demonstrated a positive relationship between an imaging biomarker for diffuse fibrosis (CMR ECV) and an established serum biomarker (NT-proBNP) for heart failure. Our results suggest that NT-proBNP identifies a subclinical profibrotic condition in a community population. Further clarification will importantly assist in understanding the significance and utility of these biomarkers in studying the pathogenesis of fibrosis in heart failure.

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE:

Blood levels of NT-proBNP are associated with myocardial fibrosis detected by CMR even in a cohort of mainly asymptomatic individuals.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

The link between NT-proBNP and extracellular volume may enhance understanding of the evolution of myocardial fibrosis in the transition from subclinical to clinical disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all investigators, staff, and participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions.

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grant R01 HL127659 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Bluemke has received research support (nonfinancial) from and has been on the speakers bureau for Siemens. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- ECV

extracellular volume fraction

- EDV

end-diastolic volume

- ESV

end-systolic volume

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

left ventricular

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

REFERENCES

- 1.Schelbert EB, Cao JJ, Sigurdsson S, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance in older adults. JAMA 2012; 308:890–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turkbey EB, Nacif MS, Guo M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of myocardial scar in a US cohort. JAMA 2015;314:1945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iles L, Pfluger H, Phrommintikul A, et al. Evaluation of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with cardiac magnetic resonance contrast-enhanced T1 mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jellis C, Martin J, Narula J, Marwick TH. Assessment of nonischemic myocardial fibrosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan JH, Vasu S, Morgan TM, et al. Anthracycline-associated T1 mapping characteristics are elevated independent of the presence of cardiovascular comorbidities in cancer survivors. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:e004325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chahal H, Bluemke DA, Wu CO, et al. Heart failure risk prediction in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Heart 2015;101:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirakawa K, Yamamuro M, Uemura T, et al. Correlation between microvascular dysfunction and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in nonischemic heart failure patients with cardiac fibrosis. Int J Cardiol 2017;228:881–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savarese G, Hage C, Orsini N, et al. Reductions in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels are associated with lower mortality and heart failure hospitalization rates in patients with heart failure with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e003105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radosavljevic-Radovanovic M, Radovanovic N, Vasiljevic Z, et al. Usefulness of NT-proBNP in the follow-up of patients after myocardial infarction. J Med Biochem 2016;35:158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastormerlo LE, Maffei S, Latta DD, et al. N-terminal fragment of B-type natriuretic peptide predicts coexisting subclinical heart and vessel disease.J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2017;18:750–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krittayaphong R, Boonyasirinant T, Saiviroonporn P, Thanapiboonpol P, Nakyen S, Udompunturak S. Correlation between NT-pro BNP levels and left ventricular wall stress, sphericity index and extent of myocardial damage: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Card Fail 2008;14:687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henkel DM, Glockner J, Miller W. Association of myocardial fibrosis, B-type natriuretic peptide, and cardiac magnetic resonance parameters of remodeling in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:390–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walther T, Klostermann K, Heringer-Walther S, Schultheiss HP, Tschope C, Stepan H. Fibrosis rather than blood pressure determines cardiac BNP expression in mice. Regul Pept 2003;116:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain T, Dragulescu A, Benson L, et al. Quantification and significance of diffuse myocar-dial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol 2015;36:970–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treibel TA, Zemrak F, Sado DM, et al. Extra-cellular volume quantification in isolated hyper-tension: changes at the detectable limits? J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bluemke DA, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. The relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to incident cardiovascular events: the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu CY, Liu YC, Wu C, et al. Evaluation of age-related interstitial myocardial fibrosis with cardiac magnetic resonance contrast-enhanced T1 mapping: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Maestrini V, et al. Automatic measurement of the myocardial inter-stitium: synthetic extracellular volume quantification without hematocrit sampling. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2016;9:54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabir D, Child N, Kalra A, et al. Reference values for healthy human myocardium using a T1 mapping methodology: results from the International T1 Multicenter cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2014;16:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AbouEzzeddine OF, McKie PM, Scott CG, et al. Biomarker-based risk prediction in the community. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:1342–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi EY, Bahrami H, Wu CO, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular mass, and incident heart failure: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis . Circ Heart Fail 2012;5: 727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell A, Misialek JR, Folsom AR, et al. Usefulness of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and myocardial perfusion in asymptomatic adults (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am J Cardiol 2015;115:1341–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinnunen P, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H. Mechanisms of atrial and brain natriuretic peptide release from rat ventricular myocardium: effect of stretching. Endocrinology 1993;132:1961–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rommel KP, von Roeder M, Latuscynski K, et al. Extracellular volume fraction for characterization of patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67: 1815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conrad CH, Brooks WW, Hayes JA, Sen S, Robinson KG, Bing OH. Myocardial fibrosis and stiffness with hypertrophy and heart failure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circulation 1995; 91:161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng M, Qiao Y, Wen Z, et al. The association between diffuse myocardial fibrosis on cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping and myocardial dysfunction in diabetic rabbits. Sci Rep 2017;7:44937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Hattab D, Czubryt MP. A primer on current progress in cardiac fibrosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2017:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwak HB. Aging, exercise, and extracellular matrix in the heart. J Exerc Rehabil 2013;9: 338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the Multi-Ethnic Study Of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 2008;168: 2138–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safford MM, Brown TM, Muntner PM, et al. Association of race and sex with risk of incident acute coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2012; 308:1768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akwo EA, Kabagambe EK, Wang TJ, et al. Heart failure incidence and mortality in the southern community cohort study. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]