Abstract

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed malignancy among women in the United States. Approximately 70% of breast tumors express estrogen receptor alpha and are deemed ER-positive. ER-positive breast tumors depend upon endogenous estrogens to promote ER-mediated cellular proliferation. Decades of research have led to a fundamental understanding of the role ER signaling in this disease and this knowledge has led to significant advancements in the clinical use of antiestrogens for breast cancer treatment. However, adjuvant breast cancer recurrence and metastatic disease progression due to endocrine therapy resistance are prominent and unresolved issues. The established role that estrogens play in breast cancer pathogenesis explains why some patients initially respond to endocrine therapy but also why a significant number of patients become refractory to antiestrogen treatment. It is been hypothesized that exposure to environmental steroid hormone mimics and/or acquired mechanisms of resistance may explain why endocrine therapy fails in a subset of breast cancer patients. This review will highlight: 1) the relationship between ER signaling and breast cancer pathogenesis, 2) the implication of environmental exposures on steroid hormone regulated processes including breast cancer, and 3) the unresolved issue of endocrine therapy resistance.

Keywords: endocrine disruption, anti-androgens, estrogens, estrogenicity, estrogen receptor-α, breast cancer

Introduction

Estrogen and other steroid hormones are lipophilic small molecules that are primarily produced in the gonads and adrenal glands (Miller and Auchus, 2011). Steroid hormones are well known to play prominent roles in reproduction, organ development, and the regulation of normal physiological processes. Organs and tissues such as the brain (Solum and Handa, 2002), lungs (Carey et al., 2007), gonads (Alves et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013), and breast (Macias and Hinck, 2012) are just a few examples of targets which steroid hormones act upon. Some of these same hormones have also been shown to be critically involved in the development or progression of steroid hormone-dependent diseases such as prostate (Shi et al., 2013) and breast cancer (Lippman et al., 2001). For example, cumulative lifetime exposure to estrogens has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women (Lippman et al., 2001). The importance of estrogens in breast cancer progression is highlighted by the fact that approximately 70% of all breast tumors express the estrogen receptor and proliferate in the presence of estrogenic hormones (Dowsett et al., 2010). There has been increasing interest and debate as to whether environmental exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can alter normal steroid hormone regulated processes and contribute to estrogen-dependent diseases such as breast cancer. Here, we will discuss the relationship between estrogen and breast cancer, the potential role of environmental estrogen mimics on breast cancer progression, and review the current understanding of suspected estrogenic EDCs on altering normal human physiology and estrogen regulated pathways.

Transport and Metabolism of Estrogen

Due to the lipophilic nature of steroid hormones, they can readily diffuse across cellular membranes and into systemic circulation (Oren et al., 2004). Unlike peptide hormones, which are generally highly water-soluble, steroid hormones are poorly soluble in blood due to their lipophilic nature. Therefore, most steroid hormones are reversibly bound to carrier proteins in the plasma which are in equilibrium with the free and bound state of a given hormone (Mendel, 1989). Albumin, sex hormone-binding globulin, and corticosteroid-binding globulin are examples of carrier proteins that transport steroid hormones in the blood (Hammond, 2016). However, it is the unbound, or free steroid, that diffuse out of the capillaries to elicit their biological effects on target tissues and cells expressing their cognate receptors, including sex steroid nuclear receptors.

Some estrogen target tissues are known to modify estrogens to hydroxylated catechol estrogens via oxidation reactions by cytochrome P450 enzymes (Lepine et al., 2004). Furthermore, conjugation of estrogens and their oxidized metabolites can be achieved by sulfotransferase and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase phase II enzymes which generally inactivate and convert these hormones into polar, water soluble metabolites that aids in their excretion (Cheng et al., 1998; Lepine et al., 2004). Estrogens that have been conjugated with a sulfate or glucuronide moiety are representative of the most common types of conjugated circulating estrogens (Lepine et al., 2004).

The Estrogen Receptor

ERß

There are two main subtypes of ER known as estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor ß (ERß) (Pinton et al., 2018). The first reports of the cloning and sequencing of ERα occurred in 1986 by two separate groups (Green et al., 1986; Greene et al., 1986), while Kuiper et al. were the first to clone and identify ERß from rat prostate several years later in 1996 (Kuiper et al., 1996). Recent reports have identified at least five isoforms of ERß that further add to the complexity of the possible regulatory roles of ERß (Baek et al., 2015). However, most research groups do agree that ERß primarily exhibits antiproliferative, pro-apoptotic, and tumor suppressive functions by opposing and antagonizing ERα mediated pathways (Nakajima et al., 2011; Paech, 1997). It has been suggested that ERß achieves these opposing actions by sequestering estrogen (E2) or by forming heterodimers with ERα to exert a negative regulatory effect on ERα function (Miller et al., 2017; Omoto et al., 2003). Despite these findings, major issues with the cell lines and inadequately validated antibodies for ERß were recently described (Nelson et al., 2017). Nelson et al. showed that one of the main antibodies used to detect ERß, NCL-ER-BETA, is non-specific for this receptor (Nelson et al., 2017). Using antibodies verified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, Nelson et al. also showed that ERß was not expressed in either MCF-7 or LNCaP cell lines which have been commonly used to study ERß and potentially calls into question some of the conclusions made in studies using NCL-ER-BETA antibody (Nelson et al., 2017). The findings by Nelson et al. likely explain much of the uncertainty and inconsistencies regarding the role of ERß in breast and prostate cancer (Haldosen et al., 2014) and contributes to the rationale for this review focusing on ERα in the context of EDCs instead.

ERα66

ERα66 is a nuclear receptor and transcription factor that is primarily localized to the cellular nucleus and is comprised of six unique domains that serve separate functions (Green et al., 1986; Greene et al., 1986). The A/B domain includes the region of the receptor known as activation function–1 (AF-1) that contains a serine residue at position 118 (Ser118). Phosphorylation of Ser118 (ERα-P-Ser118) has been shown to be critical for proper function of ER where this receptor modification is likely controlled in part by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with CDK7 or IKK-α (Chen et al., 2000; Weitsman et al., 2006). Weitsman et al. used chromatin immunoprecipitation to show that ERα-P-Ser118 binds to known ERα coactivators proteins, specifically p300 and steroid receptor coactivator-3 (Yi et al., 2015), to provide evidence of the functional involvement of ERα-P-Ser118 in estrogen regulated pathways (Weitsman et al., 2006). The DNA binding domain (DBD) is in the C domain of ERα66 and is responsible for binding to the estrogen response element (ERE) located at the promotor region of estrogen regulated genes. The interaction of the DBD with an ERE occurs through recognition of the consensus palindromic sequence identified as GGTCAnnnTGACC (O'Lone et al., 2004). Additionally, the D domain hinge region has been implicated in the recruitment of transcription factors such as c-Jun and contains the nuclear localization sequence which aids in the translocation of ERα to the nucleus (Burns et al., 2011).

The ligand binding domain (LBD) and activation function-2 (AF-2) region of ERα66 are both located in the E domain of this receptor. However, the functions of the LBD and AF-2 of ERα66 are primarily activated upon binding of endogenous estrogens (Delfosse et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2011). Brzozowski et al. were the first to report the crystal structure for the LBD of ERα66 in complex with E2 using x-ray diffraction (Brzozowski et al., 1997). They noted that the helical arrangement of ERα66 formed a hydrophobic ligand binding cavity that complemented the lipophilic characteristic of E2. The shape of this binding site cavity appeared to favor the formation of specific hydrogen bonds with E2 which are key to orienting the bound hormone (Brzozowski et al., 1997; Kumar et al., 2011). The binding of a high affinity agonist such as E2 induces a conformational change in ER that stabilizes the positioning of helix 12 (H12) which has been shown to be a critical LBD helix whose positioning directly influences the transcriptional activity of ERα66 (Delfosse et al., 2015). The stabilization of H12 exposes a hydrophobic grove between helices H3, H4, and H12 that recognizes and recruits coactivators that contain LxxLL helical motifs to the AF-2 region (Delfosse et al., 2015; Warnmark et al., 2002). In contrast, the binding of antagonists destabilizes the positioning of H12 which prevents LxxLL coactivator association with ER and favors the recruitment of transcriptional corepressors as observed with the ER antagonist tamoxifen and its more potent active metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Shang et al., 2000). The final domain of ERα66 is known as the F domain which has been suggested to be involved in modulating the positioning of H12 and activity of ERα66 (Nichols et al., 1998). Targeted mutations of the F domain have been shown to alter the affinity of E2 and ER antagonists such as tamoxifen or even preventing the interaction of some coactivator proteins (Koide et al., 2007; Montano et al., 1995; Schwartz et al., 2002).

The Role of Estrogen and the ER Pathway in Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy among women in the United States (US) with an estimated 266,000 new diagnoses and 41,000 deaths in 2018 alone (Siegel et al., 2018). Despite these numbers, the mortality rate for breast cancer has been steadily declining over the last three decades (Siegel et al., 2018). The reported decline in the mortality rate has largely been attributed to early detection, significant advancements in patient treatment, and a greater understanding of the biological mechanisms driving different breast tumor types (DeSantis et al., 2015).

Endocrine Therapy Resistance and Recurrence in HR+ Breast Cancer

Although ERα-P-Ser118 is an example of a prognostic marker that was reported to predict which breast cancer patients might benefit from endocrine therapy at diagnosis (Yamashita et al., 2008), additional biological markers are needed to identify which patients are more likely to experience a recurrence of their cancer. For instance, Pan et al. showed that there is a persistent risk of recurrence and death from breast cancer for at least 20 years after receiving 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy (Pan et al., 2017). This persistent risk of breast recurrence was determined to increase at a rate of approximately 1 – 2% every year (Cuzick et al., 2010) irrespective of a patient’s nodal status and stage (Pan et al., 2017). The biological mechanisms underlying the constant rate of recurrence in patients with HR+ tumors, however, are not well understood. For breast cancer patients taking aromatase inhibitors (AIs), it has been suggested that non-classical estrogens arising from androgen metabolism (Sikora et al., 2009), might explain why upwards of 20% of these patients will recur within 10 years of receiving endocrine therapy (Cuzick et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2017). Here, we further hypothesize that exposure to estrogen mimicking EDCs may also play an important role in HR+ breast cancer recurrence.

Environmental Estrogenic EDCs and Breast Cancer Risk and Progression

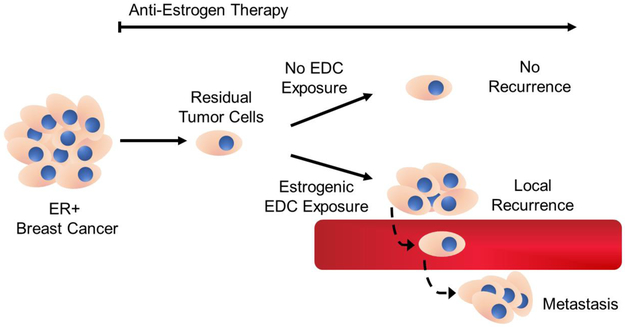

Mechanistically, AIs do not prevent the binding of estrogens to ER and instead work by minimizing their biological synthesis. Therefore, low concentrations of residual circulating estrogens and/or exposure to environmental estrogenic EDCs may offer another potential explanation as to why endocrine therapy fails in some breast cancer patients (Figure 1). This hypothesis is supported by epidemiological studies linking EDC exposure and breast cancer risk and poor prognosis. For instance, López-Carrillo et al. conducted a case-control study among women living in the northern states of Mexico and showed that exposure to diethyl phthalate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Lopez-Carrillo et al., 2010). Likewise, Cohn et al. conducted as prospective nested case-control study in Alameda County, California, and showed that maternal exposure to the potent ERα agonist, o,p′-DDT, was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer among the daughters of the exposed women (Cohn et al., 2015). Palmer et al. conducted a follow-up cohort study and reported that prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a potent nonsteroidal ERα agonist, was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer among women greater than 40 years of age (Palmer et al., 2006). Another meta-analysis of 16 studies reported a pooled odds ratio that indicated a greater risk of breast cancer from several different PCBs (Leng et al., 2016). Additionally, adipose tissue concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from nonmetastatic breast cancer patients in New York were associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence (Muscat et al., 2003).

Figure 1. Potential relationship between estrogenic EDC exposure and ER+ breast cancer recurrence.

Timeline illustrating suspected mechanism of ER+ breast tumor recurrence in the presence or absence of estrogenic EDC exposure.

Multiple biological mechanisms linking EDC exposure to dysregulated ER signaling have been described, including receptor agonism, antagonism, and alterations in estrogen transport and metabolism. Although many EDCs have been determined to have receptor binding affinities several order of magnitude weaker than endogenous hormones such as estrogens and androgens, the ubiquitous and chronic exposure to environmental EDCs guides much of this research (Wang et al., 2016). Here, we review the known effects relevant to ER signaling caused by exposure to multiple classes of EDCs.

Diethylstilbestrol

DES is a nonsteroidal synthetic estrogen given to women in the US between 1940 to 1970 with the intent of preventing miscarriages (Schug et al., 2016). However, in the late 1960s, several young women between the ages of 15-22, who were seen at the Massachusetts General Hospital, were reported with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina, which was previously not observed in patients under the age of 30 (Herbst and Scully, 1970; Poskanzer and Herbst, 1977). It was later determined that all of the mothers of these young women had received DES during their first trimester of pregnancy. Gestational exposure to DES is associated with a range of health issues in both sons and daughters of women exposed to DES (Schug et al., 2016). Among the daughters, infertility and reproductive tract abnormalities, such as a T-shaped uterus, were associated with maternal DES exposure (Kaufman et al., 1977; Palmer, 2001). Among the sons, DES exposure was associated with an increased likelihood for the formation of non-cancerous epididymal cysts with some inconsistent findings as whether DES exposure was associated with infertility and genital abnormalities (cryptorchidism and hypospadias) (Gill et al., 1979; Vessey et al., 1983; Wilcox et al., 1995). Unlike the other EDCs discussed below, DES has a very high affinity for ERα, estimated to be approximately 4.6 times greater than estradiol (Kuiper et al., 1997).

DDT and its Analogs

DDT and it analogs are organochlorine insecticides which were widely used from the 1940s to late 1970s for insect and malaria control (Rogan and Chen, 2005). Today, most countries have banned the use of DDT primarily over ecological concerns (Rogan and Chen, 2005). Although its common trade name is DDT, technical grade DDT typically contains a mixture of several isomers with the largest percentage of the mixture being attributed to p,p′-DDT (Harada et al., 2016). Some reports have found that chronic exposure to DDT has been associated with tumor formation in the liver and adverse reproductive effects in wildlife (Turusov et al., 1973; Vos et al., 2000).

Technical grade DDT contains ~15% o,p′-DDT, an isomer of p,p′-DDT, which has been shown to act as an ERα agonist in competitive receptor binding assays (Kelce et al., 1995). Data showing that o,p′-DDT is an ERα agonist suggests that it is a component of technical grade DDT contributing to endocrine disrupting effects in observed in fish and wildlife (Harada et al., 2016; Vos et al., 2000). Due to their lipophilic nature, environmental persistence, and the reintroduction of these compounds in some parts of the world for malaria control, human exposure to DDT and its analogs remains as a topic of relevance and concern among environmental researchers (Harada et al., 2016; Rogan and Chen, 2005).

Methoxychlor

Methoxychlor is the p,p′-dimethoxy analog of p,p′-DDT that was originally intended to be a replacement for DDT due to its low acute toxicity, short biological half-life, and decreased potential for bioaccumulation (Stuchal et al., 2006). Several studies have determined that metabolites of methoxychlor are ERα agonists and likely provided a basis for its ban when it was denied reregistration by the US EPA in 2004 (Stuchal et al., 2006). Wilson et al. used a luciferase reporter assay to show evidence that HPTE, a metabolite of methoxychlor, binds to ERα and promotes estrogen-dependent gene activation that could be inhibited by co-treating with a potent antiestrogen (Wilson et al., 2004). Further in vivo data has shown that the male pups of female rats exposed to methoxychlor exhibit reduced weight of the testis, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate (Chapin et al., 1997). In female pups, methoxychlor treatment lead to a mixture of estrogenic and antiestrogenic effects which included accelerated vaginal opening, constant estrus, and atrophy of the uterus and ovaries in normal intact females (Chapin et al., 1997; Gray et al., 1989; Gray et al., 1988). In contrast, methoxychlor induced an estrogenic effect in ovariectomized female rats that was determined by an increase of uterine weight (Gray et al., 1988).

UV-filters

UV-filters are a class of chemicals that absorb a broad spectrum of UV radiation, which is why they are widely used in personal care products (PCPs) such as sunscreens, lotions, lipsticks, and creams (Dodson et al., 2012; Witorsch and Thomas, 2010). The lipophilic properties of UV-filter compounds allow to them to be ready absorbed across the skin and serves as a major route exposure in humans (Liao and Kannan, 2014; Witorsch and Thomas, 2010). Several UV-filter compounds have been shown to exhibit weak estrogenic behavior, including benzophenone-3 (BP3) which is one of most common UV-filter compounds found in PCPs (Park et al., 2013; Schlumpf et al., 2001). In vitro studies have shown that UV-filter compounds BP-3, 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (4-MBC), and octyl-methoxycinnamate (OMC) can promote increased cell proliferation of estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells and induce a uterotrophic effect in immature rats (Schlumpf et al., 2001). Wielogórska et al. characterized BP-3, 4-MBC, and OMC using an ERE-luciferase reporter assay and also showed evidence of weak estrogenic behavior for these three UV-filter compounds (Wielogorska et al., 2015). Interestingly, an epidemiological study reported a possible association between a metabolite of BP-3, benzophone-1, and an increased risk of endometriosis in women (Kunisue et al., 2012). The potential relationship between UV-filter compounds with estrogen-dependent diseases such as endometriosis requires further mechanistic studies to elucidate the possible mechanisms underlying this observation.

Bisphenols

Bisphenol-A (BPA) is widely used in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics used in bottles and toys, epoxy resins used in the lining of metal cans, and in numerous other plastic consumer products (Vandenberg et al., 2012). Several studies have provided evidence that BPA behaves as a weak estrogen and is able to bind to ERα (Delfosse et al., 2014; Delfosse et al., 2012). Naciff et al. studied pregnant rats and compared changes in global gene expression profiles from tissues of pups that were exposed in utero to BPA and two other ERα agonists 17 α-ethynyl estradiol (EE) and the phytoestrogen genistein (Naciff et al., 2005). They found that all three compounds significantly upregulated the same 50 ER-regulated genes which suggests BPA has a common mode of action with known ERα agonists such as EE and genistein (Naciff et al., 2005).

Murray et al. previously studied the relationship between the weak estrogenic behavior of BPA and its effect on mammary gland development by exposing rats to 2.5 μg/kg BW/day of BPA during gestation (Murray et al., 2007). They found that adult rats (postnatal day 95) exposed to BPA during gestation were observed with an increase of intraductal hyperplasias in the mammary glands. Tissue sections from epithelial cells in the intraductal hyperplasias were determined by immunostaining to have significantly higher expression of ERα compared to normal mammary glands with additional evidence of increased proliferative activity. They concluded that the increased expression of ERα in the hyperplastic tissues suggest that the proliferative activity among these cells might be driven by estrogen and that these tissues are more likely to be stimulated by estrogens later in life (Murray et al., 2007). Murray et al. also speculated that their findings support the hypothesis that fetal exposure to BPA and estrogen mimics may contribute to an increased risk of breast cancer later in life that might be attributed to altered mammary gland morphology. This same group conducted a similar study in nonhuman primates which were exposed to BPA during gestation and observed subtle but significant differences in morphological parameters in mammary gland density versus unexposed controls (Tharp et al., 2012). Although morphometric analysis indicated that the overall development of the mammary gland tissue was more advanced in the BPA treatment groups, immunostaining did not show evidence of increased ERα expression as reported in their earlier rodent study. Taken together, these in vivo findings are relevant in the context of breast cancer development in humans in light of evidence that high mammographic density is associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer (McCormack and dos Santos Silva, 2006).

Chronic BPA exposure has also been linked to an increased risk of metastatic breast cancer in the genetically susceptible mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-erbB2 overexpressing mice (Jenkins et al., 2011). Mice chronically exposed to low level BPA (2.5 and 25 μg BPA/L drinking water) had an increased number of lung metastases relative to control animals. Low dose BPA exposure led to an increase expression of phosphorylated Akt and GSK3B. Intriguingly, similar effects were not observed at higher doses of BPA, suggesting that the relationship between BPA exposure and breast cancer progression may follow a nonmonotonic response curve (Jenkins et al., 2011).

The concern over the potential endocrine disrupting effects attributed to BPA has led to a reduction in its commercial use and the recent implementation of BPA substitutes bisphenol-S (BPS) and bisphenol-F (BPF) in numerous consumer goods (Rochester and Bolden, 2015). Interestingly, comprehensive reviews of the reported literature suggests that both BPS and BPF exhibit similar hormonal activity as BPA where they have been found to induce similar effects such as promoting an increase in uterine weight in rats (Rochester and Bolden, 2015) and activating ERα in MCF-7 cells (Mesnage et al., 2017). The widespread exposure of bisphenols and their potential endocrine disrupting effect on humans remains as current issue that warrants further investigation (Liao et al., 2012).

Parabens

Parabens, and their analogs, are alkyl esters of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid that are commonly used as preservatives in numerous consumer products including lotions, creams, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, shampoos, sunscreens, and several other types of PCPs (Dodge et al., 2018; Dodson et al., 2012; Nishihama et al., 2016). The widespread use of parabens in PCPs has led to research studies to determine the extent of human exposure and investigate whether there is evidence for endocrine disrupting behavior (Witorsch and Thomas, 2010). In vitro studies have shown that parabens exhibit weak estrogenic behavior, bind to ERα to promote ER-dependent gene transcription, and induce increased cellular proliferation of ER-dependent breast cancer cells (Delfosse et al., 2014; Gonzalez et al., 2018; Watanabe et al., 2013; Wielogorska et al., 2015; Wrobel and Gregoraszczuk, 2014). Evidence of estrogenic behavior for n-butylparaben in vivo was observed when Hu et al. treated immature Sprague Dawley rats at a dose of 0.16 mg/kg/day for three days via intragastric administration (Hu et al., 2013). Hu et al. found that n-butylparaben was able to induce an estrogenic response in the immature rats which was assessed by an increase of uterine weight (Hu et al., 2013).

Although parabens are rapidly metabolized in humans, studies have detected their presence in adipose, placental and breast tissue, as well as breast milk, serum, seminal fluid, and urine (Artacho-Cordon et al., 2017; Charles and Darbre, 2013; Frederiksen et al., 2011; Hines et al., 2015; Honda et al., 2018; Meeker et al., 2011; Valle-Sistac et al., 2016). A common finding among many biomonitoring studies is that urinary concentrations of parabens in women tends to be several-fold higher than in samples from men (Honda et al., 2018; Moos et al., 2016). Other reports suggest differential exposure among women exposed to parabens and related environmental phenols and these appear to be associated with age, race/ethnicity and geographic location (Buttke et al., 2012; Calafat et al., 2010; Mortensen et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2019). In men, n-butylparaben has been associated with markers of DNA damage in sperm (Meeker et al., 2011). Similarly, reduced sperm production in male rats has been shown when they are exposed to either propylparaben or n-butylparaben in their diet (Oishi, 2001, 2002; Smarr et al., 2018). Despite these findings, Nishihama et al. did not detect an association between male urinary paraben exposure and semen parameters, however, the study’s small sample size may have limited the power to detect a true association (Nishihama et al., 2017).

Among third trimester pregnant women, higher concentrations of parabens measured in maternal urine and cord blood were associated with an increased risk of pre-term birth, reduced birth weight, and decreased birth length (Geer et al., 2017). Nishihama et al. provided evidence that parabens exhibit endocrine disrupting behavior when they reported a dose dependent association between paraben exposure and shorter self-reported menstrual cycle lengths among female Japanese university students (Nishihama et al., 2016). Interestingly, Pollock et al. treated female mice with 3 mg of n-butylparaben by subcutaneous injection and found that urinary E2 concentrations were elevated in the mice 6 hours after the initial treatment (Pollock et al., 2017). These in vivo findings support the human data presented by Nishihama et al. which suggests that parabens may influence normal reproductive function. Moreover, these data suggest paraben exposure may have additional implications in estrogen-dependent diseases such as breast cancer. For example, breast tissue concentrations of iso-butylparaben and n-butylparaben measured in patients with ER + PR+ primary breast tumors have been detected at relevant effect concentrations determined in in vitro studies (Charles and Darbre, 2013). For example, iso-butylparaben and n-butylparaben were measured in breast tissue samples at concentrations near their experimentally determined half maximal effective concentration (EC50) or EC30 respectively (Gonzalez et al., 2018). However, control breast tissue samples from healthy women were not included in this study which makes it difficult to determine if weakly estrogenic compounds like parabens have a role in breast cancer or not. The ubiquitous human and wildlife (Xue and Kannan, 2016; Xue et al., 2015) exposure to estrogenic paraben compounds and their associations with potentially altering estrogen regulated processes warrants further investigation.

Indirect Modulation of Estrogenic Activity by EDCs

Although paraben compounds have been reported to exhibit their estrogenic behavior by directly binding to ERα, it has been suggested that these compounds may also exert their estrogenic effects by inhibiting E2 metabolism (Prusakiewicz et al., 2007). Prusakiewicz et al. showed that n-butylparaben inhibits sulfotransferase (SULT) activity in normal human epidermal keratinocytes at low micromolar concentrations which may increase the bioavailability of non-sulfated estrogens in SULT expressing tissues. Similarly, Kester et al. showed that several hydroxylated polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons may partially exert their estrogenic effects by inhibiting estrogen sulfotransferase SULT1E1 despite their low affinity for ERα (Kester et al., 2002). In contrast, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), has been shown to behave as an anti-estrogen by interfering with ER signaling (Gottel et al., 2014) which can result in the inhibition of the expression of the ER regulated gene cathepsin D (Wang et al., 2001).

Future Research Directions to Link EDC Exposure and Breast Cancer Recurrence

Most diagnosed breast tumors express ER and cell proliferation in these tumors is induced by endogenous estrogens. Similarly, EDCs that exhibit estrogenic behavior, including some of the compounds described above, are suspected to play role in ER-dependent tumor progression. A number of potential EDCs have been detected in human breast tissue, however, human exposure to these compounds are not always associated with clinical and pathological characteristics in breast cancer (Ellsworth et al., 2015). Currently, there are a lack of studies demonstrating that exposure to EDCs is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer incidence or metathesis despite their detection in breast tissue (Charles and Darbre, 2013; Darbre et al., 2004) at biologically relevant concentrations (Gonzalez et al., 2018).

Significant gaps remain in our understanding of EDC exposure and ER+ breast cancer recurrence. First, in vitro and in vivo results suggest that many EDCs exhibit non-monotonic dose-response effects (Vandenberg et al., 2012), which have yet to be adequately captured in epidemiological studies of EDC exposure in breast cancer patients. Second, the effects of exposure to complex mixtures of EDCs are not well characterized. Recent evidence suggests that mixtures of EDCs (BPA, methylparaben, and perfluorooctanoic acid) at concentrations relevant to human exposure have synergistic effects on both normal breast and breast cancer cells (Dairkee et al., 2018). Future mechanistic work should focus on modeling the effects of chemical mixtures at doses relevant to human exposures. Third, the specific mechanisms by which EDCs could impact metastatic ER+ tumor growth are not well understood. Specifically, determining whether EDC exposure in ER+ patients promotes tumor cell dissemination (Kang and Pantel, 2013) or emergence from dormancy (Zhang et al., 2013) will be essential to define mechanistic links between EDC exposure and breast cancer recurrence. Well-designed mechanistic and epidemiological studies are needed to provide evidence whether exposure to EDCs and/or estrogen mimics contribute to breast cancer recurrence, contralateral breast cancer, or metastatic breast cancer in women receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Numbers T32ES007062, R01ES028802 (to JAC), and P30ES017885, as well as the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF) (N003173 to JMR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG and Cunningham FG 2009. Pregnancy and Laboratory Studies: A Reference Table for Clinicians. Obstet. Gynecol 114, 1326–1331, 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2bde8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves MG, Rato L, Carvalho RA, Moreira PI, Socorro S and Oliveira PF 2013. Hormonal control of Sertoli cell metabolism regulates spermatogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 70, 777–793, 10.1007/s00018-012-1079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Prat A, Perou CM and Sherman ME 2014. How Many Etiological Subtypes of Breast Cancer: Two, Three, Four, Or More? J. Natl. Cancer Inst 106, diu165–diu165, 10.1093/jnci/dju165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artacho-Cordon F, Arrebola JP, Nielsen O, Hernandez P, Skakkebaek NE, Fernandez MF, Andersson AM, Olea N and Frederiksen H 2017. Assumed non-persistent environmental chemicals in human adipose tissue; matrix stability and correlation with levels measured in urine and serum. Environ. Res 156, 120–127, 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek JM, Chae BJ, Song BJ and Jung SS 2015. The potential role of estrogen receptor β2 in breast cancer. Int. J. Surg 14, 17–22, 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA and Carlquist M 1997. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature 389, 753–758, 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KA, Li Y, Arao Y, Petrovich RM and Korach KS 2011. Selective mutations in estrogen receptor alpha D-domain alters nuclear translocation and non-estrogen response element gene regulatory mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem 286, 12640–12649, 10.1074/jbc.M110.187773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L and Santoro N 2011. The reproductive endocrinology of the menopausal transition. Steroids 76, 627–635, 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttke DE, Sircar K and Martin C 2012. Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and age of menarche in adolescent girls in NHANES (2003-2008). Environ. Health Perspect 120, 1613–1618, 10.1289/ehp.1104748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Bishop AM and Needham LL 2010. Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the U.S. population: NHANES 2005-2006. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 679–685, 10.1289/ehp.0901560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, Germolec DR, Korach KS and Zeldin DC 2007. The impact of sex and sex hormones on lung physiology and disease: lessons from animal studies. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol 293, L272–L278, 10.1152/ajplung.00174.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carranza-Lira S, Hernandez F, Sanchez M, Murrieta S, Hernandez A and Sandoval C 1998. Prolactin secretion in molar and normal pregnancy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet 60, 137–141, 10.1016/S0020-7292(97)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin RE, Harris MW, Davis BJ, Ward SM, Wilson RE, Mauney MA, Lockhart AC, Smialowicz RJ, Moser VC, Burka LT and Collins BJ 1997. The Effects of Perinatal/Juvenile Methoxychlor Exposure on Adult Rat Nervous, Immune, and Reproductive System Function. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 40, 138–157, 10.1006/faat.1997.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AK and Darbre PD 2013. Combinations of parabens at concentrations measured in human breast tissue can increase proliferation of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J. Appl. Toxicol 33, 390–398, 10.1002/jat.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Riedl T, Washbrook E, Pace PE, Coombes RC, Egly JM and Ali S 2000. Activation of Estrogen Receptor α by S118 Phosphorylation Involves a Ligand-Dependent Interaction with TFIIH and Participation of CDK7. Mol. Cell 6, 127–137, 10.1016/S1097-2765(05)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Rios GR, King CD, Coffman BL, Green MD, Mojarrabi B, Mackenzie PI and Tephly TR 1998. Glucuronidation of catechol estrogens by expressed human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) 1A1, 1A3, and 2B7. Toxicol. Sci 45, 52–57, 10.1006/toxs.1998.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn BA, La Merrill M, Krigbaum NY, Yeh G, Park JS, Zimmermann L and Cirillo PM 2015. DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 100, 2865–2872, 10.1210/jc.2015-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M and Forbes JF 2010. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet. Oncol 11, 1135–1141, 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairkee SH, Luciani-Torres G, Moore DH, Jaffee IM and Goodson WH 3rd. 2018. A Ternary Mixture of Common Chemicals Perturbs Benign Human Breast Epithelial Cells More Than the Same Chemicals Do Individually. Toxicol. Sci 165, 131–144, 10.1093/toxsci/kfy126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, Coldham NG, Sauer MJ and Pope GS 2004. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J. Appl. Toxicol 24, 5–13, 10.1002/jat.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfosse V, Grimaldi M, Cavailles V, Balaguer P and Bourguet W 2014. Structural and functional profiling of environmental ligands for estrogen receptors. Environ. Health Perspect 122, 1306–1313, 10.1289/ehp.1408453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfosse V, Grimaldi M, Pons JL, Boulahtouf A, le Maire A, Cavailles V, Labesse G, Bourguet W and Balaguer P 2012. Structural and mechanistic insights into bisphenols action provide guidelines for risk assessment and discovery of bisphenol A substitutes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 109, 14930–14935, 10.1073/pnas.1203574109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfosse V, le Marie A, Balaguer P and Bourguet W 2015. A structural perspective on nuclear receptors as targets of environmental compounds. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 36, 88–104, 10.1038/aps.2013.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Bray F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Anderson BO and Jemal A 2015. International Variation in Female Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 24, 1495–1506, 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge LE, Choi JW, Kelley KE, Hernandez DIS and Hauser R 2018. Medications as a potential source of exposure to parabens in the U.S. population. Environ. Res 164, 580–584, 10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG and Rudel RA 2012. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ. Health Perspect 120, 935–943, 10.1289/ehp.1104052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, Coates A, Forbes J, Bliss J, Buyse M, Baum M, Buzdar A, Colleoni M, Coombes C, Snowdon C, Gnant M, Jakesz R, Kaufmann M, Boccardo F, Godwin J, Davies C and Peto R 2010. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J. Clin. Oncol 28, 509–518, 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth RE, Mamula KA, Costantino NS, Deyarmin B, Kostyniak PJ, Chi LH, Shriver CD and Ellsworth DL 2015. Abundance and distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in breast tissue. Environ Res 138, 291–297, 10.1016/j.envres.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat GN, Cauley JA 2008. The link between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Cases. Miner. Bone Metab 5, 19–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen H, Jorgensen N and Andersson AM 2011. Parabens in urine, serum and seminal plasma from healthy Danish men determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 21, 262–271, 10.1038/jes.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geer LA, Pycke BFG, Waxenbaum J, Sherer DM, Abulafia O and Halden RU 2017. Association of birth outcomes with fetal exposure to parabens, triclosan and triclocarban in an immigrant population in Brooklyn, New York. J. Hazard. Mater 323, 177–183, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill WB, Schumacher GF, Bibbo M, Straus FH 2nd, and Schoenberg HW 1979. Association of Diethylstilbestrol Exposure in Utero With Cryptorchidism, Testicular Hypoplasia and Semen Abnormalities. J. Urol 122, 36–39, 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)56240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez TL, Moos RK, Gersch CL, Johnson MD, Richardson RJ, Koch HM and Rae JM 2018. Metabolites of n-Butylparaben and iso-Butylparaben Exhibit Estrogenic Properties in MCF-7 and T47D Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Toxicol. Sci 164, 50–59, 10.1093/toxsci/kfy063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottel M, Le Corre L, Dumont C, Schrenk D and Chagnon MC 2014. Estrogen receptor alpha and aryl hydrocarbon receptor cross-talk in a transfected hepatoma cell line (HepG2) exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol. Rep 1, 1029–1036, 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LE Jr., Ostby J, Ferrell J, Rehnberg G, Linder R, Cooper R, Goldman J, Slott V and Laskey J 1989. A dose-response analysis of methoxychlor-induced alterations of reproductive development and function in the rat. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 12, 92–108, 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LE Jr., Ostby JS, Ferrell JM, Sigmon ER and Goldman JM 1988. Methoxychlor induces estrogen-like alterations of behavior and the reproductive tract in the female rat and hamster: Effects on sex behavior, running wheel activity, and uterine morphology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 96, 525–540, 10.1016/0041-008X(88)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A, Bornert JM, Argos P and Chambon P 1986. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature 320, 134, 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GL, Gilna P, Waterfield M, Baker A, Hort Y and Shine J 1986. Sequence and Expression of Human Estrogen Receptor Complementary DNA. Science 231, 1150–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldosen LA, Zhao C and Dahlman-Wright K 2014. Estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 382, 665–672, 10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond GL 2016. Plasma steroid-binding proteins: primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. J. Endocrinol. 230, R13–25, 10.1530/JOE-16-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Takeda M, Kojima S and Tomiyama N 2016. Toxicity and Carcinogenicity of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). Toxicol. Res 32, 21–33, 10.5487/TR.2016.32.1.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst AL and Scully RE 1970. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina in adolescence. A report of 7 cases including 6 clear-cell carcinomas (so-called mesonephromas). Cancer 25, 745–757, . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EP, Mendola P, von Ehrenstein OS, Ye X, Calafat AM and Fenton SE 2015. Concentrations of environmental phenols and parabens in milk, urine and serum of lactating North Carolina women. Reprod. Toxicol 54, 120–128, 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Robinson M and Kannan K 2018. Parabens in human urine from several Asian countries, Greece, and the United States. Chemosphere 201, 13–19, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhang Z, Sun L, Zhu D, Liu Q, Jiao J, Li J and Qi M 2013. The estrogenic effects of benzylparaben at low doses based on uterotrophic assay in immature SD rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 53, 69–74, 10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins S, Wang J, Eltoum I, Desmond R and Lamartiniere CA 2011. Chronic oral exposure to bisphenol A results in a nonmonotonic dose response in mammary carcinogenesis and metastasis in MMTV-erbB2 mice. Environ Health Perspect 119, 1604–1609, 10.1289/ehp.1103850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y and Pantel K 2013. Tumor cell dissemination: emerging biological insights from animal models and cancer patients. Cancer Cell 23, 573–581, 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RH, Binder GL, Gray PM and Adam E 1977. Upper genital tract changes associated with exposure in uteroto diethylstilbestrol. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 128, 51–59, 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelce WR, Stone CR, Laws SC, Gray LE, Kemppainen JA and Wilson EM 1995. Persistent DDT metabolite p,p'–DDE is a potent androgen receptor antagonist. Nature 375, 581, 10.1038/375581a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kester MH, Bulduk S, van Toor H, Tibboel D, Meinl W, Glatt H, Falany CN, Coughtrie MW, Schuur AG, Brouwer A and Visser TJ 2002. Potent inhibition of estrogen sulfotransferase by hydroxylated metabolites of polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons reveals alternative mechanism for estrogenic activity of endocrine disrupters. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 1142–1150, 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide A, Zhao C, Naganuma M, Abrams J, Deighton-Collins S, Skafar DF and Koide S 2007. Identification of regions within the F domain of the human estrogen receptor alpha that are important for modulating transactivation and protein-protein interactions. Mol. Endocrinol 21, 829–842, 10.1210/me.2006-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Haggblad J, Nilsson S and Gustafsson JA 1997. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology 138, 863–870, 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S and Gustafsson JA 1996. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 93, 5925–5930, 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Zakharov MN, Khan SH, Miki R, Jang H, Toraldo G, Singh R, Bhasin S and Jasuja R 2011. The dynamic structure of the estrogen receptor. J. Amino Acids. 2011, 812540, 10.4061/2011/812540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisue T, Chen Z, Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Hediger ML, Sun L and Kannan K 2012. Urinary concentrations of benzophenone-type UV filters in U.S. women and their association with endometriosis. Environ. Sci. Technol 46, 4624–4632, 10.1021/es204415a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L'Hermite M 2013. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric 16 Suppl 1, 44–53, 10.3109/13697137.2013.808563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng L, Li J, Luo XM, Kim JY, Li YM, Guo XM, Chen X, Yang QY, Li G and Tang NJ 2016. Polychlorinated biphenyls and breast cancer: A congener-specific meta-analysis. Environ. Int 88, 133–141, 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepine J, Bernard O, Plante M, Tetu B, Pelletier G, Labrie F, Belanger A and Guillemette C 2004. Specificity and regioselectivity of the conjugation of estradiol, estrone, and their catecholestrogen and methoxyestrogen metabolites by human uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases expressed in endometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 89, 5222–5232, 10.1210/jc.2004-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, He H, Zhang Y-L, Li X-M, Guo X, Huo R, Bi Y, Li J, Fan H-Y and Sha J 2013. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase p110δ Mediates Estrogen- and FSH-Stimulated Ovarian Follicle Growth. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1468–1482, 10.1210/me.2013-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C and Kannan K 2014. Widespread Occurrence of Benzophenone-Type UV Light Filters in Personal Care Products from China and the United States: An Assessment of Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 4103–4109, 10.1021/es405450n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Liu F, Guo Y, Moon HB, Nakata H, Wu Q and Kannan K 2012. Occurrence of Eight Bisphenol Analogues in Indoor Dust from the United States and Several Asian Countries: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 9138–9145, 10.1021/es302004w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman ME, Krueger KA, Eckert S, Sashegyi A, Walls EL, Jamal S, Cauley JA and Cummings SR 2001. Indicators of lifetime estrogen exposure: effect on breast cancer incidence and interaction with raloxifene therapy in the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation study participants. J. Clin. Oncol 19, 3111–3116, 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Carrillo L, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Calafat AM, Torres-Sanchez L, Galvan-Portillo M, Needham LL, Ruiz-Ramos R and Cebrian ME 2010. Exposure to phthalates and breast cancer risk in northern Mexico. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 539–544, 10.1289/ehp.0901091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias H and Hinck L 2012. Mammary gland development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol 1, 533–557, 10.1002/wdev.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack VA and dos Santos Silva I 2006. Breast Density and Parenchymal Patterns as Markers of Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1159–1169, 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Yang T, Ye X, Calafat AM and Hauser R 2011. Urinary concentrations of parabens and serum hormone levels, semen quality parameters, and sperm DNA damage. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 252–257, 10.1289/ehp.1002238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendel CM 1989. The Free Hormone Hypothesis: A Physiologically Based Mathematical Model. Endocr. Rev 10, 232–274, 10.1210/edrv-10-3-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage R, Phedonos A, Arno M, Balu S, Corton JC and Antoniou MN 2017. Editor's Highlight: Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Bisphenol A Alternatives Activate Estrogen Receptor Alpha in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Toxicol. Sci 158, 431–443, 10.1093/toxsci/kfx101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MM, McMullen PD, Andersen ME and Clewell RA 2017. Multiple receptors shape the estrogen response pathway and are critical considerations for the future of in vitro-based risk assessment efforts. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 47, 570–586, 10.1080/10408444.2017.1289150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL and Auchus RJ 2011. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr. Rev. 32, 81–151, 10.1210/er.2010-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Barbieri RL and Hankinson SE 2004. Endogenous estrogen, androgen, and progesterone concentrations and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96, 1856–1865, 10.1093/jnci/djh336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano MM, Muller V, Trobaugh A and Katzenellenbogen BS 1995. The Carboxy-Terminal F-Domain of the HUman Estrogen Receptor: Role in the Transcriptional Activity of the Receptor and the Effectivness of Antiestrogens as Estrogen Antagonists. Mol. Endocrinol. 9, 814–825, 10.1210/mend.9.7.7476965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RK, Apel P, Schroter-Kermani C, Kolossa-Gehring M, Bruning T and Koch HM 2016. Daily intake and hazard index of parabens based upon 24 h urine samples of the German Environmental Specimen Bank from 1995 to 2012. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 27, 10.1038/jes.2016.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen ME, Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Wright DJ, Pirkle JL, Merrill LS and Moye J 2014. Urinary concentrations of environmental phenols in pregnant women in a pilot study of the National Children's Study. Environ. Res 129, 32–38, 10.1016/j.envres.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray TJ, Maffini MV, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C and Soto AM 2007. Induction of mammary gland ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ following fetal bisphenol A exposure. Reprod. Toxicol 23, 383–390, 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Britton JA, Djordjevic MV, Citron ML, Kemeny M, Busch-Devereaux E, Pittman B and Stellman SD 2003. Adipose Concentrations of Organochlorine Compounds and Breast Cancer Recurrence in Long Island, New York. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 12, 1474–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naciff JM, Hess KA, Overmann GJ, Torontali SM, Carr GJ, Tiesman JP, Foertsch LM, Richardson BD, Martinez JE and Daston GP 2005. Gene Expression Changes Induced in the Testis by Transplacental Exposure to High and Low Doses of 17α-Ethynyl Estradiol, Genistein, or Bisphenol A. Toxicol. Sci 86, 396–416, 10.1093/toxsci/kfi198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Akaogi K, Suzuki T, Osakabe A, Yamaguchi C, Sunahara N, Ishida J, Kako K, Ogawa S, Fujimura T, Homma Y, Fukamizu A, Murayama A, Kimura K, Inoue S and Yanagisawa J 2011. Estrogen Regulates Tumor Growth Through a Nonclassical Pathway that Includes the Transcription Factors ERβ and KLF5. Sci. Signal 4, ra22, 10.1126/scisignal.2001551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AW, Groen AJ, Miller JL, Warren AY, Holmes KA, Tarulli GA, Tilley WD, Katzenellenbogen BS, Hawse JR, Gnanapragasam VJ and Carroll JS 2017. Comprehensive assessment of estrogen receptor beta antibodies in cancer cell line models and tissue reveals critical limitations in reagent specificity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 440, 138–150, 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VK, Colacino JA, Arnot JA, Kvasnicka J and Jolliet O 2019. Characterization of age-based trends to identify chemical biomarkers of higher levels in children. Environ. Int 122, 117–129, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M, Rientjes JM and Stewart AF 1998. Different positioning of the ligand-binding domain helix 12 and the F domain of the estrogen receptor accounts for functional differences between agonists and antagonists. EMBO J. 17, 765–773, 10.1093/emboj/17.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama Y, Toshima H, Yoshinaga J, Mizumoto Y, Yoneyama M, Nakajima D, Shiraishi H and Tokuoka S 2017. Paraben exposure and semen quality of Japanese male partners of subfertile couples. Environ. Health Prev. Med 22, 5, 10.1186/s12199-017-0618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama Y, Yoshinaga J, Iida A, Konishi S, Imai H, Yoneyama M, Nakajima D and Shiraishi H 2016. Association between paraben exposure and menstrual cycle in female university students in Japan. Reprod. Toxicol 63, 107–113, 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary P, Boyne P, Flett P, Beilby J and James I 1991. Longitudinal assessment of changes in reproductive hormones during normal pregnancy. Clin. Chem. 37, 667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Lone R, Frith MC, Karlsson EK and Hansen U 2004. Genomic Targets of Nuclear Estrogen Receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1859–1875, 10.1210/me.2003-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S 2001. Effects of butylparaben on the male reproductive system in rats. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 17, 31–39, 10.1191/0748233701th093oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S 2002. Effects of propyl paraben on the male reproductive system. Food Chem. Toxicol. 40, 1807–1813, 10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto Y, Eguchi H, Yamamoto-Yamaguchi Y and Hayashi S 2003. Estrogen receptor (ER) β1 and ERβcx/β2 inhibit ERα function differently in breast cancer cell line MCF7. Oncogene 22, 5011, 10.1038/sj.onc.1206787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren I, Fleishman SJ, Kessel A and Ben-Tal N 2004. Free diffusion of steroid hormones across biomembranes: a simplex search with implicit solvent model calculations. Biophys. J. 87, 768–779, 10.1529/biophysj.103.035527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GGJM, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS 1997. Differential Ligand Activation of Estrogen Receptors ERα and ERβ at AP1 Sites. Science 277, 1508–1510, 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JR, Hatch EE, Rao RS, Kaufman RH, Herbst AL, Noller KL, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hoover RN 2001. Infertility among Women Exposed Prenatally to Diethylstilbestrol. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154, 316–321, 10.1093/aje/154.4.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JR, Wise LA, Hatch EE, Troisi R, Titus-Ernstoff L, Strohsnitter W, Kaufman R, Herbst AL, Noller KL, Hyer M and Hoover RN 2006. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol exposure and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1509–1514, 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, Davies C, Taylor C, McGale P, Peto R, Pritchard KI, Bergh J, Dowsett M and Hayes DF 2017. 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence after Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1836–1846, 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MA, Hwang KA, Lee HR, Yi BR, Jeung EB and Choi KC 2013. Benzophenone-1 stimulated the growth of BG-1 ovarian cancer cells by cell cycle regulation via an estrogen receptor alpha-mediated signaling pathway in cellular and xenograft mouse models. Toxicology 305, 41–48, 10.1016/j.tox.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM and Borresen-Dale AL 2011. Systems Biology and Genomics of Breast Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3, 10.1101/cshperspect.a003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton G, Nilsson S and Moro L 2018. Targeting estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) for treatment of ovarian cancer: importance of KDM6B and SIRT1 for ERβ expression and functionality. Oncogenesis 7, 15, 10.1038/s41389-018-0027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock T, Weaver RE, Ghasemi R and deCatanzaro D 2017. Butyl paraben and propyl paraben modulate bisphenol A and estradiol concentrations in female and male mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 325, 18–24, 10.1016/j.taap.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poskanzer DC and Herbst AL 1977. Epidemiology of vaginal adenosis and adenocarcinoma associated with exposure to stilbestrol in utero. Cancer 39, 1892–1895, . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusakiewicz JJ, Harville HM, Zhang Y, Ackermann C and Voorman RL 2007. Parabens inhibit human skin estrogen sulfotransferase activity: possible link to paraben estrogenic effects. Toxicology 232, 248–256, 10.1016/j.tox.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester JR and Bolden AL 2015. Bisphenol S and F: A Systematic Review and Comparison of the Hormonal Activity of Bisphenol A Substitutes. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 643–650, 10.1289/ehp.1408989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan WJ and Chen A 2005. Health risks and benefits of bis(4-chlorophenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (DDT). Lancet 366, 763–773, 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE Jr., Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN and Wolmark N 2005. Trastuzumab plus Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Operable HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1673–1684, 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W, Hankinson SE, Sluss PM, Vesper HW and Wierman ME 2013. Challenges to the measurement of estradiol: an endocrine society position statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 98, 1376–1387, 10.1210/jc.2012-3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpf M, Cotton B, Conscience M, Haller V, Steinmann B and Lichtensteiger W 2001. In vitro and in vivo Estrogenicity of UV Screens. Environ. Health Perspect 109, 239–244, 10.1289/ehp.01109239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schug TT, Johnson AF, Birnbaum LS, Colborn T, Guillette LJ Jr., Crews DP, Collins T, Soto AM, Vom Saal FS, McLachlan JA, Sonnenschein C and Heindel JJ 2016. Minireview: Endocrine Disruptors: Past Lessons and Future Directions. Mol Endocrinol 30, 833–847, 10.1210/me.2016-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JA, Zhong L, Deighton-Collins S, Zhao C and Skafar DF 2002. Mutations targeted to a predicted helix in the extreme carboxyl-terminal region of the human estrogen receptor-alpha alter its response to estradiol and 4-hydroxytamoxifen. J. Biol. Chem 277, 13202–13209, 10.1074/jbc.M112215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA and Brown M 2000. Cofactor Dynamics and Sufficiency in Estrogen Receptor-Regulated Transcription. Cell 103, 843–852, 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Han JJ, Tennakoon JB, Mehta FF, Merchant FA, Burns AR, Howe MK, McDonnell DP and Frigo DE 2013. Androgens Promote Prostate Cancer Cell Growth through Induction of Autophagy. Mol. Endocrinol 27, 280–295, 10.1210/me.2012-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A 2018. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin 68, 7–30, 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora MJ, Cordero KE, Larios JM, Johnson MD, Lippman ME and Rae JM 2009. The androgen metabolite 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol (3betaAdiol) induces breast cancer growth via estrogen receptor: implications for aromatase inhibitor resistance. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 115, 289–296, 10.1007/s10549-008-0080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarr MM, Honda M, Kannan K, Chen Z, Kim S and Louis GMB 2018. Male urinary biomarkers of antimicrobial exposure and bi-directional associations with semen quality parameters. Reprod. Toxicol. 77, 103–108, 10.1016/j.reprotox.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solum DT and Handa RJ 2002. Estrogen regulates the development of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 22, 2650–2659, 10.1523/jneurosci.22-07-02650.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lonning PE and Borresen-Dale AL 2001. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. PNAS 98, 10869–10874, 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchal LD, Kleinow KM, Stegeman JJ and James MO 2006. Demethylation of the pesticide methoxychlor in liver and intestine from untreated, methoxychlor-treated, and 3-methylcholanthrenetreated channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus): evidence for roles of CYP1 and CYP3A family isozymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 34, 932–938, 10.1124/dmd.105.009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp AP, Maffini MV, Hunt PA, VandeVoort CA, Sonnenschein C and Soto AM 2012. Bisphenol A alters the development of the rhesus monkey mammary gland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 109, 8190–8195, 10.1073/pnas.1120488109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turusov VS, Day NE, Tomatis L, Gati E and Charles RT 1973. Tumors in CF-1 Mice Exposed for Six Consecutive Generations to DDT. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 51, 983–997, 10.1093/jnci/51.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle-Sistac J, Molins-Delgado D, Diaz M, Ibanez L, Barcelo D and Silvia Diaz-Cruz M 2016. Determination of parabens and benzophenone-type UV filters in human placenta. First description of the existence of benzyl paraben and benzophenone-4. Environ. Int 88, 243–249, 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR Jr., Lee DH, Shioda T, Soto AM, vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, Zoeller RT and Myers JP 2012. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev 33, 378–455, 10.1210/er.2011-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey MP, Fairweather DVI, Norman-Smith B and Buckley J 1983. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of the value of stilboestrol therapy in pregnancy: long-term follow-up of mothers and their offspring. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol 90, 1007–1017, 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1983.tb06438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JG, Dybing E, Greim HA, Ladefoged O, Lambre C, Tarazona JV, Brandt I and Vethaak AD 2000. Health Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals on Wildlife, with Special Reference to the European Situation. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 30, 71–133, 10.1080/10408440091159176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Yang L, Wang S, Zhang Z, Yu Y, Wang M, Cromie M, Gao W and Wang SL 2016. The classic EDCs, phthalate esters and organochlorines, in relation to abnormal sperm quality: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci. Rep 6, 19982, 10.1038/srep19982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Samudio I and Safe S 2001. Transcriptional activation of cathepsin D gene expression by 17β-estradiol: mechanism of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated inhibition. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 172, 91–103, 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnmark A, Treuter E, Gustafsson JA, Hubbard RE, Brzozowski AM and Pike AC 2002. Interaction of Transcriptional Intermediary Factor 2 Nuclear Receptor Box Peptides with the Coactivator Binding Site of Estrogen Receptor α. J. Biol. Chem 277, 21862–21868, 10.1074/jbc.M200764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Kojima H, Takeuchi S, Uramaru N, Ohta S and Kitamura S 2013. Comparative study on transcriptional activity of 17 parabens mediated by estrogen receptor alpha and beta and androgen receptor. Food Chem. Toxicol 57, 227–234, 10.1016/j.fct.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiderpass E, Adami HO, Baron JA, Magnusson C, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Correia N and Persson I 1999. Risk of Endometrial Cancer Following Estrogen Replacement With and Without Progestins. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91, 1131–1137, 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitsman GE, Li L, Skliris GP, Davie JR, Ung K, Niu Y, Curtis-Snell L, Tomes L, Watson PH and Murphy LC 2006. Estrogen receptor-alpha phosphorylated at Ser118 is present at the promoters of estrogen-regulated genes and is not altered due to HER-2 overexpression. Cancer Res. 66, 10162–10170, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielogorska E, Elliott CT, Danaher M and Connolly L 2015. Endocrine disruptor activity of multiple environmental food chain contaminants. Toxicol. In Vitro 29, 211–220, 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Hornsby PP and Herbst AL 1995. Fertility in Men Exposed Prenatally to Diethylstilbestrol. N. Engl. J. Med 332, 1411–1416, 10.1056/NEJM199505253322104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson VS, Bobseine K and Gray LE Jr. 2004. Development and Characterization of a Cell Line That Stably Expresses an Estrogen-Responsive Luciferase Reporter for the Detection of Estrogen Receptor Agonist and Antagonists. Toxicol. Sci 81, 69–77, 10.1093/toxsci/kfh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witorsch RJ and Thomas JA 2010. Personal care products and endocrine disruption: A critical review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 40 Suppl 3, 1–30, 10.3109/10408444.2010.515563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel AM and Gregoraszczuk EL 2014. Actions of methyl-, propyl- and butylparaben on estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta and the progesterone receptor in MCF-7 cancer cells and non-cancerous MCF-10A cells. Toxicol. Lett 230, 375–381, 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J and Kannan K 2016. Accumulation profiles of parabens and their metabolites in fish, black bear, and birds, including bald eagles and albatrosses. Environ. Int 94, 546–553, 10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J, Sasaki N, Elangovan M, Diamond G and Kannan K 2015. Elevated Accumulation of Parabens and their Metabolites in Marine Mammals from the United States Coastal Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12071–12079, 10.1021/acs.est.5b03601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Hibi H, Katsuno S and Miyake K 1995. Serum estradiol levels in normal men and men with idiopathic infertility. Int. J. Urol 2, 44–46, 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1995.tb00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Nishio M, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Kondo N, Kobayashi S, Fujii Y and Iwase H 2008. Low phosphorylation of estrogen receptor α (ERα) serine 118 and high phosphorylation of ERα serine 167 improve survival in ER-positive breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 15, 755–763, 10.1677/ERC-08-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi P, Wang Z, Feng Q, Pintilie GD, Foulds CE, Lanz RB, Ludtke SJ, Schmid MF, Chiu W and O'Malley BW 2015. Structure of a Biologically Active Estrogen Receptor-Coactivator Complex on DNA. Mol. Cell. 57, 1047–1058, 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XH, Giuliano M, Trivedi MV, Schiff R and Osborne CK 2013. Metastasis dormancy in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 19, 6389–6397, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]