Abstract

Elimination of airway inflammatory cells is essential for asthma control. As Bcl-2 protein is highly expressed on the mitochondrial outer membrane in inflammatory cells, we chose a Bcl-2 inhibitor, ABT-199, which can inhibit airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness by inducing inflammatory cell apoptosis. Herein, we synthesized a pH-sensitive nanoformulated Bcl-2 inhibitor (Nf-ABT-199) that could specifically deliver ABT-199 to the mitochondria of bronchial inflammatory cells. The proof-of-concept study of an inflammatory cell mitochondria-targeted therapy using Nf-ABT-199 was validated in a mouse model of allergic asthma. Nf-ABT-199 was proven to significantly alleviate airway inflammation by effectively inducing eosinophil apoptosis and inhibiting both inflammatory cell infiltration and mucus hypersecretion. In addition, the nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 showed no obvious influence on cell viability, airway epithelial barrier and liver function, implying excellent biocompatibility and with non-toxic effect. The nanoformulated Bcl-2 inhibitor Nf-ABT-199 accumulates in the mitochondria of inflammatory cells and efficiently alleviates allergic asthma.

Keywords: ABT-199, Bcl-2, Nanotechnology, Targeted drug delivery Mitochondria, Allergic airway inflammation

1. Introduction

Asthma is a serious disease that affects millions of people worldwide, and the number of affected individuals continues to increase [1,2]. The global prevalence rates of doctor-diagnosed asthma and clinically treated asthma in adults are 4.3% and 4.5%, respectively and these rates continue increasing [3,4]. The majority of asthmatics respond well to inhaled corticosteroids. These treatment are occasionally combined with long- or short-acting β-agonist (LABA or SABA) bronchodilators and leukotriene antagonists (LTRAs), which are regarded as the first-line strategy for controlling asthma [5]. However, some asthmatics still exhibit poorly controlled asthma, even with the maximal dose of oral corticosteroids [5]. Importantly, this group of patients accounts for more than 60% of asthma-related healthcare expenses [6]. In addition to inhaled corticosteroids, humanized neutralizing monoclonal antibodies and antagonists against specific cytokines/chemokines are utilized to treat moderate to severe refractory asthma. However, these strategies can only achieve limited success due to the heterogeneity of asthma [2,7,8].

Recently, nanotechnologies have been applied to develop the personalized medicines [9–12]. And they have also been used in the diagnosis and treatment of asthma [13–15]. For instance, thiolated chitosan nanoparticles [16], chitosan interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-plasmid DNA (pDNA) nanoparticles [17], and heparin-loaded chitosan-cyclodextrin nanoparticles [16], have been used as pulmonary drug delivery systems to prolong the residence time of drugs in airways for enhanced anti-inflammatory effects. However, most of drug delivery systems for asthma only improve the microscopic biodistribution of the drugs in airways but do not target hypersensitive intracellular organelles. Consequently, such treatments do not show significantly high therapeutic outcomes. Considering the serious adverse effects and limited therapeutic range of oral/systemic corticosteroids, a general and highly efficient asthma treatment is urgently needed.

To date, 25 members of the Bcl-2 protein family have been found to localize on the mitochondrial outer membrane, smooth endoplasmic reticulum and perinuclear membranes in hematopoietic cells [18,19]. Bcl-2 has been widely studied in tumor pathophysiology and which also confer chemoresistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia [20]. ABT-199, a Bcl-2 protein inhibitor, binds to these proteins and induces the release of cytochrome C following mitochondrial fragmentation [21]. Cytochrome C then activates caspase-9 and caspase-3, which leads to inflammatory cell apoptosis [22]. Indeed, the increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (B cell lymphoma 2) has been observed in inflammatory cell types [23]. We therefore hypothesized that the Bcl-2 inhibitors might have therapeutic effect for a broad range of asthma severities by inducing inflammatory cell apoptosis in the context of airway inflammation. In this study, we present evidence that a nanoformulated Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-199 (Nf-ABT-199) accumulates in the mitochondria of inflammatory cells and efficiently alleviates airway inflammation by inducing eosinophil apoptosis, inhibiting inflammatory cell infiltration and mucus hypersecretion (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1. A schematic representation of mitochondria-targeted nanoformulated ABT-199 (Nf-ABT-199) for asthma therapy, as well as its synthesis and characterization.

(A) The production of Nf-ABT-199 through self-assembly and administration of Nf-ABT-199 into an asthma model mouse. (B) The administration of Nf-ABT-199 leads to effective targeting of the mitochondria in inflammatory cells and subsequently induces a significant alleviation of inflammatory cell recruitment, mucus production and airway hyperresponsiveness. (C) DLS measurement of Nf-ABT-199 size after 10-fold dilution and TEM imaging of Nf-ABT-199. (D) Zeta-potentials of Nf-ABT-199 at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 (n = 3).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.2. PEG5K-p (API-Asp)5 synthesis

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.3. Synthesis of fluorescent, rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RITC)-labeled PEG5K-p(API-Asp)5

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.4. Preparation of Nf-ABT-199

ABT-199 (5 mg) and PEG5K-p(API-Asp)5 (10 mg) were dissolved in a mixture of DMSO (3 mL) and methanol (1 mL). After stirring for 10 min, the methanol was removed via rotary evaporation under a vacuum. Then, the DMSO was completely substituted with deionized water by dialysis (USA; MWCO: 3500 Da) for 2 days. Excess ligands were removed via centrifugation or washed 3 times with a spin filter (Millipore, MWCO: 100,000 Da, 10,000×g, for 10 min). The resulting nanoparticles were re-dispersed in water for subse-quent studies. RITC-labeled Nf-ABT-199 was prepared using the same process but with RITC labeled PEG5K-p(API-Asp)5 rather than PEG5K-p(API-Asp)5.

2.5. Preparation of pH-insensitive is-Nf-ABT-199

ABT-199 (5 mg) and PEG5K-PBLA (10 mg) were dissolved in a mixture of DMSO (3 mL) and methanol (1 mL). After stirring for 10 min, the methanol was removed via rotary evaporation under a vacuum. Then, the DMSO was completely substituted with deionized water by dialysis (USA; MWCO: 3500 Da) for 2 days. Excess ligands were removed via centrifugation or washed 3 times with a spin filter (Millipore, MWCO: 100,000 Da, 10,000×g, for 10 min). The resulting nanoparticles were re-dispersed in water for use in the subsequent studies.

2.6. Experimental animals

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.7. Induction of allergic airway inflammation

The mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) immunized with 20 μg (in 100 μL) of chicken ovalbumin (OVA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) emulsified in alum [2.25 mg of Al(OH)3/2 mg Mg(OH)2] (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on days 0 and 14 (OVA/Alum model group). On days 24, 25, and 26, the OVA/Alum mice were challenged with an aerosol of 1% OVA in saline for 40 min via ultrasonic nebulization (DeVilbiss, Somerset, PA, USA). The mice in the OVA/Alum-ABT-199 or OVA/Alum-Nf-ABT-199 groups were intratracheally (i.t.) administered different doses of ABT-199 (Selleck, Houston, TX, USA) or Nf-ABT-199 in 50 mL of vehicle 2 h after each OVA challenge. ABT-199 was formulated in 60% phosal 50 propylene glycol, 30% polyethylene glycol 400, and 10% ethanol [24,25]. The naive mice were sensitized and challenged with saline alone at the same time. After the last allergen challenge for 24 h, all mice were sacrificed for analysis. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lungs were collected. The OVA/Alum model was established using the eosinophilic airway inflammatory model, as previously reported [26].

2.8. BAL fluid and differential cell counts

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.9. BAL inflammatory cells culture

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.10. MitoTracker and immunofluorescence staining

As described in the Supplementary materials.

2.11. Flow cytometry analysis of BAL cells

The BAL fluid cell suspensions were obtained from either mice or in vitor cell culture medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at specific time points. The expression of cell surface markers was assessed by incubating the samples with fluorescent dye-conjugated mouse antibodies against Gr-1 (Pe-Cy7) and SiglecF (PE) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 min at 4 °C. Based on the surface marker staining, the suspensions were incubated with Annexin V (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) (MultiSciences, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) to assess BAL fluid cell apoptosis. The data were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (FC500) (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software ver. 7.6 (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA, USA).

2.12. Evaluation of mitochondrial targeting of ABT-199

The EOL-1 cells were seeded in culture flasks for 48 h at 37 °C. Nf-ABT-199, nanocarrier or ABT-199 was added at 0.01 mM per flask. After 12 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and collected by centrifugation at 600×g for 5 min. The cells were then resuspended in mitochondria isolation buffer using a mitochondria isolation kit (Beyotime, Shanghai China). The cells were subjected to 10 strokes in a cell homogenizer. The cells were centrifuged at 600×g for 5 min, and the mitochondria was separated at 11000×g for 10 min. Last, the amount of ABT-199 was evaluated by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC, Agilent Technology, 1200 Series, Diamonsil C18(2), USA).

2.13. HBE cell viability assay

HBE cells were cultured in medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS) in 96-well cell plates (2 × 104 cell/well) and treated with nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 for 12, 24, 48 h. Cell viability was analyzed by a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) under 450 nm (Infinite® F50 microplate reader, Männedorf, Switzerland).

2.14. Flow cytometry analysis of HBE apoptosis

To clarify whether nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 has apoptotic effect on epithelial cells, we conducted a FACS analysis with Annexin V (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining (MultiSciences, Hang-zhou, Zhejiang, China). Briefly, HBE cells were cultured and treated with various concentrations of nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 for 12, 24, 48 h in 6-well cell plates (1 × 105 cell/well), the results were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (FC500) and analyzed using FlowJo software ver. 7.6.

2.15. Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs). The data were analyzed with either Student’s t-test (two-tailed) or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. The reported values are from ≧ 3 separate experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Development and characterization of nanoformulated ABT-199 (Nf-ABT-199)

Nf-ABT-199 is composed of ABT-199 and a pH-sensitive polymer synthesized from generally recognized as safe (GRAS) materials. The pH-sensitive polymer (PEG5k-p(API-Asp)5) was synthesized using the following two-step reaction (Fig. S1): (i) ring opening polymerization of α-amino acid N-carboxyanhydrides (NCAs) using PEG5K-NH2 as an initiator and (ii) introduction of pH-responsive ionizable groups (imidazole groups) through an aminolysis reaction. PEG5k-p (API-Asp)5 assembles spontaneously into micelles in water with loading of ABT-199 into the hydrophobic core during the dialysis process. The amphiphilic polymer-based nano-formulation increases the dissolution rate and prolongs the residence time of drugs in the lungs [27]. The hydrodynamic diameter of the resulting Nf-ABT-199 at a physiological pH was ~220 nm (Fig. 1C), as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The par-ticle size of Nf-ABT-199 in the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image (Fig. 1C) was slightly smaller than that measured by DLS due to the hydration shell. The zeta potential of the micelle was + 17 mV (Fig. 1D), suggesting that Nf-ABT-199 exhibits a greater possibility of interacting with the negatively charged cell surface. Moreover, the potential of the micelle increased to +48 mV (Fig. 1D) when the pH decreased to 5.5 (intracellular lysosomal pH) due to the further protonation of imidazole group in Nf-ABT-199.

3.2. Mitochondria-targeted delivery of Nf-ABT-199

Human eosinophilic leukemia (EOL-1) cells were treated with rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RITC)-labeled Nf-ABT-199 (Nf-ABT-199-RITC) (10 μM) for 0, 15, 30 and 60 min. The cells were then stained with 100 nM Mito-Tracker® Green FM and subsequently analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2A, the RITC-labeled Nf-ABT-199 (Nf-ABT-199-RITC) co-localized with mitochondrial proteins in the cells. By contrast, the pH-insensitive nano-formulation (is-Nf-ABT-199; see Methods for the preparation process and Fig. S2 for the characterization of the polymer) did not exhibit obvious mitochondrial targeting effects (Fig. 2B). The excellent mitochondria-targeting effect might be attributed to the pH-sensitive imidazole groups of Nf-ABT-199, which underwent a charge switch in the acidic environment of endo/lysosomes and induced a proton sponge effect, leading to endosomal escape of Nf-ABT-199. The quantitative results (Fig. 2C) show that the uptake of Nf-ABT-199 was superior to that of the is-Nf-ABT-199. As observed via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), Nf-ABT-199-RITC was tracked to the endolysosomes 10 min post-administration, and endolysosomal escape was observed 15 min post-administration (Fig. S3). To further verify the enhanced mitochondria-targeting ability of Nf-ABT-199, the ABT-199 content in the mitochondrial fraction was quantified with HPLC (Fig. S4).

Fig. 2. Visualization of mitochondrial proteins after treatment with RITC-labeled Nf-ABT-199.

The mitochondria were stained with Mito-Tracker® Green FM, which is shown in green. (A) The co-localization (yellow) of RITC-labeled Nf-ABT-199 (red) and mitochondria in human eosinophilic leukemia (EOL-1) cells at 0, 15, 30 and 60 min, as observed by Olympus fluorescence microscopy (magnification 10 × 100). (B) The control, RITC-labeled is-Nf-ABT-199 group shows no mitochondrial targeting. The quantitative results of mean fluorescence intensity show as the (C). (Nf, nanoformulation).

3.3. Nf-ABT-199 reduced the number of inflammatory cells and inflammatory cytokine levels in the airway

Mice were treated with Nf-ABT-199-RITC via intratracheally (i.t.) administration to study the distribution of Nf-ABT-199 in vivo. Notably, the fluorescent signals of the Nf-ABT-199-RITC spread throughout the lungs immediately after i.t. administration (Fig. 5SA and B), likely reflecting the diffusion of nanoparticles into the lower respiratory tract and pulmonary alveoli. We also noted that the Nf-ABT-199 did not diffuse into other organs, such as these heart, spleen, liver, kidney or brain (Fig. S5C and D). We hypothesized that nanoformulated ABT-199 would exhibit significantly higher ther-apeutic effect than free ABT-199 due to its ability to specifically target the mitochondria. The sensitized/challenged mice were treated with various doses of either ABT-199 or Nf-ABT-199 after each allergen challenge (Fig. 3A). As expected, the numbers of total cells, eosinophils and neutrophils were significantly increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and the levels of Th2-cell-related cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-5, were elevated in the lung tissues of allergen-exposed mice compared with those in the saline- or vehicle-treated control mice (Fig. 3B–F). Nf-ABT-199 (25 μg) significantly reduced the number of inflammatory cells and cyto-kines levels, with only ¼ dosage of free ABT-199 having a similar effect as 100 μg free ABT-199 (Fig. 3B–F). The non-targeted is-Nf-ABT-199 had no effect on inflammatory cells and cytokines levels (Fig. 3B–F). With respect to other immune cells, Nf-ABT-199 decreased lymphocyte counts instead of macrophages in the airway (Fig. S6).

Fig. 3. Nf-ABT-199 reduces the number of inflammatory cells and inflammatory cytokine levels.

(A) An illustration of the asthma model and method for ABT-199 and Nf-ABT-199 administration. OVA/Alum-sensitized mice were challenged with OVA and treated with ABT-199 (i.t.) or is-Nf-ABT-199 or Nf-ABT-199 2 h after each OVA challenge. The number of total cells (B), eosinophils (C) and neutrophils (D) in the BAL were counted 24 h after the last challenge. The levels of cytokines in the liquid phase of lung homogenates were measured using ELISAs specific for IL-4 (E) and IL-5 (F). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of individual groups of mice from 3 independent experiments. (Nf, nanoformulation; n = 6–8 mice/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant).

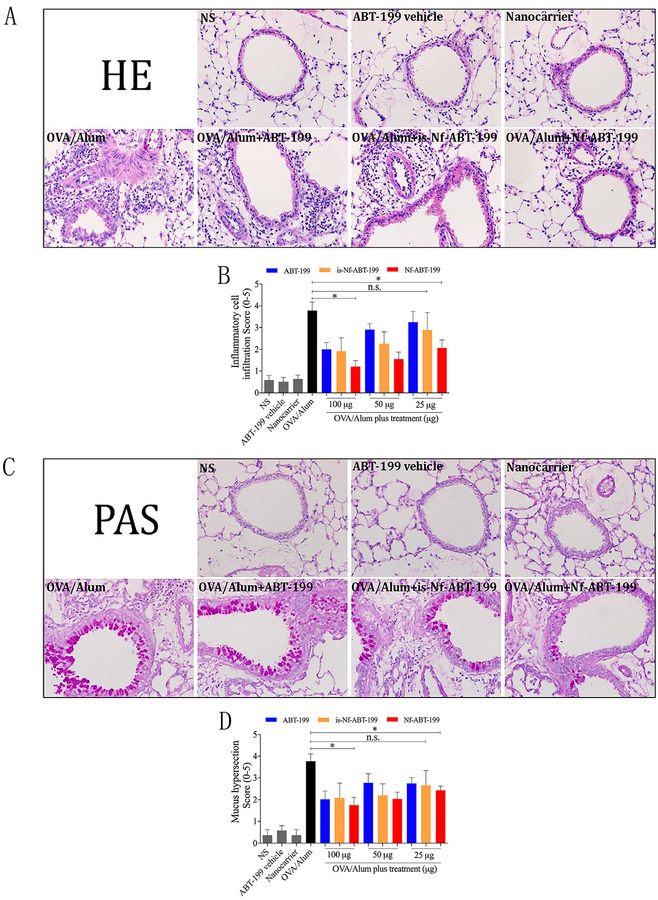

3.4. Nf-ABT-199 inhibited peribronchial inflammatory cell recruitment, mucus production and airway hyperresponsiveness

As expected, OVA-sensitized and challenged mice (OVA/Alum) displayed extensive inflammatory infiltrates in both the peribron-chial and perivascular areas of the lungs. The cellular infiltrates were decreased in the mice challenged with OVA and treated with different doses of either ABT-199 or Nf-ABT-199. However, according to the HE scoring, only ¼ of that dose was required for Nf-ABT-199 to achieve similar effects (Fig. 4A and C). Similarly, increased goblet cell hyperplasia and excess mucus production were observed in OVA-challenged mice, and treatment with either ABT-199 (100 μg) or Nf-ABT-199 (25 μg) significantly reduced these changes (Fig. 4B and D). Based on these data, Nf-ABT-199 has stronger protective effects on airway inflammation than free ABT-199. Moreover, we found that Nf-ABT-199 improved inflamma-tory cell recruitment more efficiently than free ABT-199, particularly in the small airways (Fig. S7). This effect in the small airways is due to the nanoscale diameter of Nf-ABT-199, which enables a prolonged residence time and highly efficient deposition of Nf-ABT-199 in these airways. For this reason, Nf-ABT-199 has a higher therapeutic efficiency compared with free ABT-199. Here, we also demonstrated a much lower dose of Nf-ABT-199 than of free ABT-199 was required to reduce AHR in asthma, indicating the superior efficacy of the mitochondria-specific targeted therapy; more- over, Nf-ABT-199 did not interfere with airway resistance (Fig. S8).

Fig. 4. Nf-ABT-199 reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and mucus production.

Asthma model mice were established and treated with different dosages of either ABT-199 or is-Nf-ABT-199 or Nf-ABT-199. Formalin-fixed lung tissue sections were stained with HE and PAS to visualize cell recruitment (A) and mucus hypersecretion (C) (magnification 10 × 40). The semi-quantitatively scored HE (B) and PAS (D) staining show the different efficant efficiencies of free ABT-199, is-Nf-ABT-199 and Nf-ABT-199. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of individual groups of mice from 3 independent experiments. (Nf, nanoformulation; n = 6–8 mice/group; *P < 0.05, n.s., not significant).

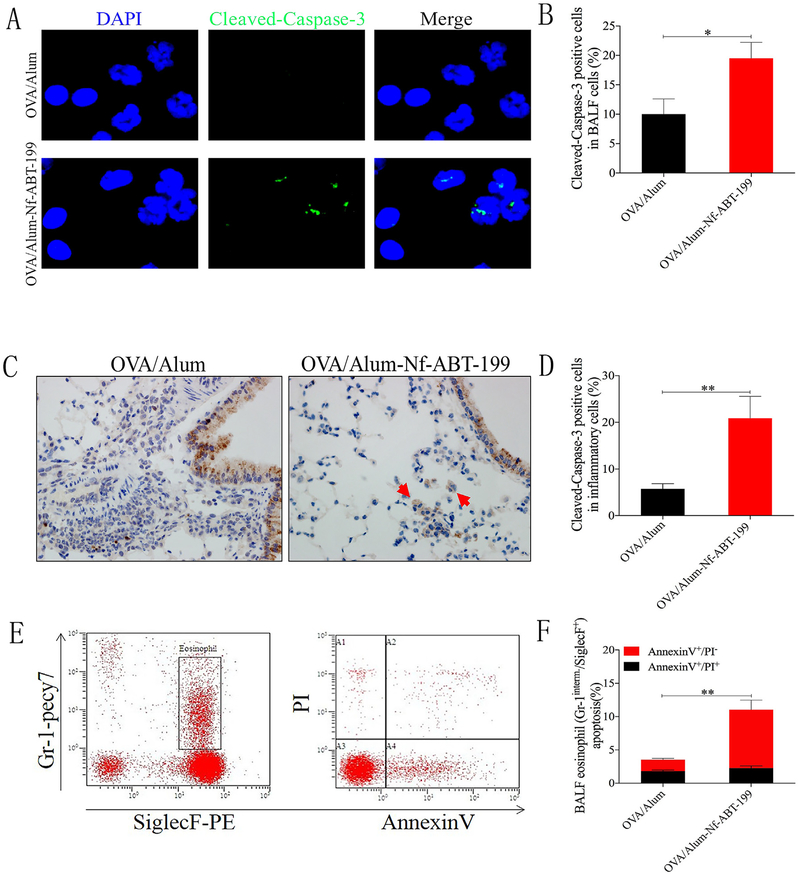

3.5. Nf-ABT-199 promoted inflammatory cell apoptosis in vivo and ex vivo

Inflammatory cell apoptosis is considerably reduced in asthmatics, which significantly contributes to the persistence of inflammation. We assessed the level of inflammatory cell apoptosis using different strategies to determine whether Nf-ABT-199 induced inflammatory cell apoptosis. Inflammatory cells in the BAL fluid and the peribronchial airways were analyzed using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as well as immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining for cleaved-caspase-3. Nf-ABT-199 (25 μg) induced cleaved caspase-3 expression in inflammatory cells, indicating that Nf-ABT-199 was very efficient in inducing inflammatory cell apoptosis (Fig. 5A–D). In addition, as shown in a FACS analysis, Nf-ABT-199 (25 μg) markedly increased eosinophil apoptosis, primarily during the early stage (AnnexinV+/PI− in Gr-1interm.+/SiglecF+) (Fig. 5E and F). As a high-affinity Bcl-2-selective BH3 mimetic, ABT-199 induced inflammatory cell apoptosis via Bcl-2 overexpression, and Nf-ABT-199 improved this pro-apoptotic effect. Based on FACS analysis, NF-ABT-199 induced eosinophil apoptosis as efficiently as ABT-199 after 12 h of treatment. The pro-apoptotic effects of ABT-199 and Nf-ABT-199 did not significantly differ (Fig. S9). We cautiously speculate that the nanoformulated ABT-199 did not have any enhanced pro-apoptotic effects ex vivo. Moreover, the vehicle treatment did not affect cell viability compared with the saline treatment.

Fig. 5. Nf-ABT-199 promotes inflammatory cell apoptosis in vivo and ex vivo.

OVA/Alum-sensitized mice were challenged with either saline or OVA and treated with Nf-ABT-199 (i.t., 25 mg/mouse) 2 h after the OVA challenges. The levels of intracellular cleaved caspase-3 in BAL cells (magnification 10×100) (A, B) and lung tissues (magnification 10×40) (C, D) were observed by immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical staining. (E, F) Representative FACS result showing that Nf-ABT-199 has an improved pro-apoptotic effect and can induce inflammatory cell apoptosis. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of individual groups of mice from 3 independent experiments. (Nf, nanoformulation; n = 6–8 mice/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

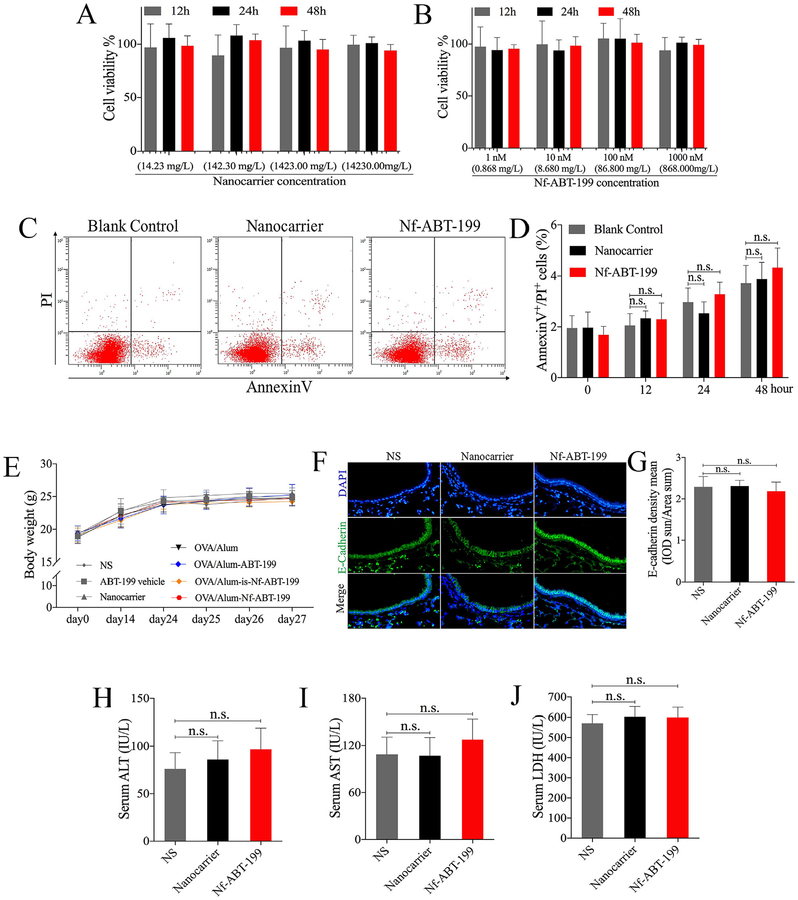

3.6. Nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 treatment showed biocompatibility in vivo and in vitro

To verify whether nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 treatment leads to harmful effect, we assessed the toxicity in vivo and in vitro. Cell counting kit (CCK-8) assay is routinely used to detect cell viability and thus investigate the safety or toxicity of pharmaceutical agents. Hence, HBE cells were incubated with various concentrations of the final product Nf-ABT-199 (ABT-199: 1 nM (0.868 mg/L), 10 nM(8.68 mg/L), 100 nM(86.8 mg/L), 1000 nM (868 mg/L) and corresponding nanocarriers (14.23 mg/L, 142.3 mg/L, 1423 mg/L, 1423 mg/L) which were set according to the drug-to-carrier ratio of ~6.1% (w/w) for different time (12, 24, 48 h). No obvious influence of Nf-ABT-199 or nanocarrier on cell viability was found (Fig. 6A and B). We screened the apoptotic level by performing AnnexinV/PI assay with FACS, and consistently, no anti-apoptotic and proapoptotic effect of Nf-ABT-199(1000 nM, 868 mg/L) or nanocarrier (1423 mg/L) was detected in HBE cells (Fig. 6C and D). As shown in animal experiments, Nf-ABT-199 or nanocarrier suggested no influence on mice body weight (Fig. 6E), and no damage to the airway epithelium was detected in terms of E-Cadherin, which represents epithelial barrier function (Fig. 6F and G), and no obvious liver injury was observed via detection of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and actate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (Fig. 6H–J). These data suggest Nf-ABT-199 and nanocarrier have no obvious toxic reactions in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 6. Nanocarrier or Nf-ABT-199 treatment does not result in obvious toxic effect.

HBE cells were treated with Nf-ABT-199 (ABT-199: 1 nM (0.868 mg/L), 10 nM(8.68 mg/L), 100 nM(86.8 mg/L), 1000 nM (868 mg/L)) and corresponding nanocarriers (14.23 mg/L, 142.3 mg/L, 1423 mg/L, 1423 mg/L) which were set according to the drug-to-carrier ratio of ~6.1% (w/w) at indicated time points. Cell viability (A, B) and apoptosis (C, D) were assessed with CCK-8 assay and FACS respectively. Body weight changes after medicine administration as shown in (E). Mice were treated with 25 mg nanocarrier or Nf-ABT −199 on days 1, 2, and 3, E-cadherin (IF) staining in lung tissues was observed and analyzed (F, G), and the concentrations of ALT (H), AST (I), LDH (J) in serum were measured 24 h after the last administration. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of individual groups of mice (n = 6–8 mice/group; n.s., not significant).

4. Discussion

The Bcl-2 protein family is enriched in the mitochondria, and free ABT-199 cannot specifically accumulate in this organelle. For these reasons, as a proof-of-concept study, we prepared a pH-sensitive nanoformulated Bcl-2 inhibitor (Nf-ABT-199) for the mitochondria-targeted treatment of asthma. The transmembrane electrical potential of intracellular mitochondria is known to be approximately 130–150 mV (negative inside) [28]. Nanoparticles with positive charges efficiently bind to mitochondria, as demonstrated in many previous studies [29–32]. Nanocarriers have been widely used for highly efficient drug delivery. Amphiphilic polymer materials are considered as outstanding drug carriers due to the excellent biocompatibility, superior drug-loading capacity and the enhanced biodistribution [33]. Here PEG and polyamino acid conjugation was chosen in our research. As well known, PEG is FDA-approved biomaterials with great safety and biocompatibility [34], and polyamino acid-based material has been widely applied as biodegradable polymers which is safe for drug and gene delivery [35,36]. Our rationally designed Nf-ABT-199 is highly sensitive to the intracellular pH, where the acidic environment of endosomes and lysosomes increase the surface charge of Nf-ABT-199 and thus lead to efficient endosomal and lysosomal escape of the nano-particles [37]. Nf-ABT-199 efficiently accumulates in the mitochondria of inflammatory cells, targeting overexpressed Bcl-2 proteins, and induces inflammatory cell apoptosis, directly leaing to the decreased infiltration of activated inflammatory cells. And it is likely that nanocarrier or nanoformulated ABT-199 does not make any difference to cell viability, apoptotic level, or barrier of airway epithelium, as well as without liver injury.

In this study, Nf-ABT-199 also reduced the levels of IL-4 and IL-5, which contribute to the pathophysiology of asthma. As demonstrated by previous studies [38], cytokines from inflammatory cells in the airway can contribute to bronchial hyper-reactivity and epithelial mucous metaplasia, which represent the primary pathological changes in asthma. Clinical trials also suggest that monoclonal antibodies targeting specific cytokines, such as IL-4 (Dupilumab) and IL-5 (Ligelizumab, Mepolizumab, Reslizumab, Benralizumab), can improve asthma symptoms [39]. In addition, the suppression of type 2 cytokines is important for asthma control [40]. AHR has long been considered a cardinal feature of asthma and seems to be correlated with airway inflammation and remodeling [41]. AHR is postulated to be regulated by genetics, airway inflammation, smooth muscles of the airway, cytokines, among other factors. The measurement of AHR provides an objective index for this disease, which is defined as an exaggerated obstructive response of the airways in response to various pharmacological, chemical and physical stimuli [13]. The response to Nf-ABT-199 indicates that the inhibitory effect on cytokines and airway inflammation may partially contribute to its protective role against AHR.

Nanoparticles have the potential for highly efficient deposition in the smaller airways and are retained in the lungs for longer periods of time [42]. Moreover, nanoparticles larger than ~34 nm remain in the lungs for more than 30 min [43]. Therefore, due to the proper size and positive surface charge of Nf-ABT-199, it can quickly disperse, exhibit enhanced retention in the lungs, and efficiently target the mitochondria of inflammatory cells. More specifically, the uptake of the positively charged Nf-ABT-199 by inflammatory cells is increased via electrostatic adsorption with the negatively charged cell membrane. After it is endocytosed into the endo/lysosome, the surface charge of Nf-ABT-199 is further increased following protonation of the polymeric carrier due to lower pH in endo/lysosome [44]. This change in charge induces endosomal and lysosomal escape of Nf-ABT-199. Subsequently, the positively charged Nf-ABT-199 accumulates in the mitochondria due to electrostatic interactions. However, free ABT-199 is not selective for targeting cells or hypersensitive intracellular organelles, and its poor solubility in water hinders its practical application in asthma treatment.

In conclusion, our study presents evidence showing for the first time that the nanoformulated Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-199 accumulates in the mitochondria of inflammatory cells, and efficiently alleviates allergic asthma much more effectively than free ABT-199 and indicates no obvious toxic effect. This effect is induced by inflammatory cell apoptosis, the down-regulation of cytokines levels, and subsequent reductions in inflammatory cell infiltration, mucus hypersecretion, and airway hyperresponsiveness. The pH sensitivity and positive surface charge of Nf-ABT-199 are critical for endosomal escape of Nf-ABT-199 in inflammatory cells for mitochondria targeting. To the best of our knowledge, this study is firstly combining nanotechnology and Bcl-2 inhibition for the treatment of airway disease. The proof of concept described in this study warrants further investigation of Bcl-2 inhibitors combined with rationally designed nanotechnology for the treatment of other inflammation-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China to DL (2016YFA0203600), SY (2016YFA0100301); the National Natural Science Foundation of China to HHS (81130001, 81490532), DL (31822019, 51503180, 51611540345), SY (31370901, 81422031, 81870007), BPT (81700023), FL (51703195), XS (51502251, 81571743), WL(91642202); the Key Project of Chinese National Programs for Fundamental Development (973 program, 2015CB553405); the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease (SK 25 LRD2016OP002); the National Key Technologies R&D Program for the 12th Five-year Plan (2012BAI05B01); the Key Science Technology Innovation Team of Zhejiang Province (2011R50016); the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (LD19H160001, SY); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2015XZZX004–16, SY; 520002*172210161, DL); the National 1000 Talents Program for Distinguished Young Scholars (DL, SY) and the Fundamental Research Funds for Xiamen University (20720160067, XS).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability’

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.020.

References

- [1].Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, The immunology of asthma, Nat. Immunol 16 (2015) 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mitchell PD, El-Gammal AI, O’Byrne PM, Emerging monoclonal antibodies as targeted innovative therapeutic approaches to asthma, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 99 (2016) 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, Boulet LP, Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey, BMC Publ. Health 12 (2012) 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hansen TE, Evjenth B, Holt J, Increasing prevalence of asthma, allergic rhi-noconjunctivitis and eczema among schoolchildren: three surveys during the period 1985–2008, Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr 102 (2013) 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tan LD, Bratt JM, Godor D, Louie S, Kenyon NJ, Benralizumab: a unique IL-5 inhibitor for severe asthma, J. Asthma Allergy 9 (2016) 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Israel E, Reddel HK, Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults, N. Engl. J. Med 377 (2017) 965–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Busse WW, Holgate S, Kerwin E, Chon Y, Feng JY, Lin J, Lin SL, Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody, in moderate to severe asthma, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 188 (2013) 1294–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Barnes PJ, Targeting cytokines to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Nat. Rev. Immunol (2018), 10.1038/s41577-018-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ryu JH, Lee S, Son S, Kim SH, Leary JF, Choi K, Kwon IC, Theranostic nanoparticles for future personalized medicine, J. Contr. Release 190 (2014) 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jo SD, Ku SH, Won YY, Kim SH, Kwon IC, Targeted nanotheranostics for future personalized medicine: recent progress in cancer therapy, Theranostics 6 (2016) 1362–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yaari Z, Da Silva D, Zinger A, Goldman E, Kajal A, Tshuva R, Barak E, Dahan N, Hershkovitz D, Goldfeder M, Roitman JS, Schroeder A, Theranostic barcoded nanoparticles for personalized cancer medicine, Nat. Commun 190 (2016) 477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].iang XHWX, Zhou WM, He YZ, Wang Y, Lv B, Effects of lipopeptide carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm, J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 31 (2017) 737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gauvreau GM, El-Gammal AI, O’Byrne PM, Allergen-induced airway responses, Eur. Respir. J 46 (2015) 819–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Da Silva AL, Martini SV, Abreu SC, Samary CDS, Diaz BL, Fernezlian S, De Sá VK, Capelozzi VL, Boylan NJ, Goya RG, Suk JS, Rocco PRM, Hanes J, Morales MM, DNA nanoparticle-mediated thymulin gene therapy prevents airway remodeling in experimental allergic asthma, J. Contr. Release 180 (2014) 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Markus MA, Napp J, Behnke T, Mitkovski M, Monecke S, Dullin C, Kilfeather S, Dressel R, Resch-Genger U, Alves F, Tracking of inhaled near-infrared fluorescent nanoparticles in lungs of SKH-1 mice with allergic airway inflammation, ACS Nano 9 (2015) 11642–11657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oyarzun-Ampuero FA, Brea J, Loza MI, Torres D, Alonso MJ, Chitosan-hyaluronic acid nanoparticles loaded with heparin for the treatment of asthma, Int. J. Pharm 38 (2009) 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kong X, Hellermann GR, Zhang W, Jena P, Kumar M, Behera A, Behera S, Lockey R, Mohapatra SS, Chitosan interferon-gamma nanogene therapy for lung disease: modulation of t-cell and dendritic cell immune responses, Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol 4 (2008) 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kale J, Osterlund EJ, Andrews DW, BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death, Cell Death Differ. 25 (2018) 65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ashkenazi A, Fairbrother WJ, Leverson JD, Souers AJ, From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16 (2017) 273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].M. S, Tahir IM, Iqbal T, Jamil A, Association of BCL-2 with oxidative stress and total antioxidant status in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents (2017) 1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Murakawa T, Yamaguchi O, Hashimoto A, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Oka T, Yasui H, Ueda H, Akazawa Y, Nakayama H, Taneike M, Misaka T, Omiya S, Shah AM, Yamamoto A, Nishida K, Ohsumi Y, Okamoto K, Sakata Y, Otsu K, Bcl-2-like protein 13 is a mammalian Atg32 homologue that mediates mitophagy and mitochondrial fragmentation, Nat. Commun 6 (2015) 7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kawamoto Y, Nakajima YI, Kuranaga E, Apoptosis in cellular society: communication between apoptotic cells and their neighbors, Int. J. Mol. Sci 17 (2016) E2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jang AS, Choi IS, Lee S, Seo JP, Yang SW, Park CS, Bcl-2 expression in sputum eosinophils in patients with acute asthma, Thorax 55 (2000) 370e374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peirs S, Matthijssens F, Goossens S, Van De Walle I, Ruggero K, De Bock CE, Degryse S, Canté-Barrett K, Briot D, Clappier E, Lammens T, De Moerloose B, Benoit Y, Poppe B, Meijerink JP, Cools J, Soulier J, Rabbitts TH, Taghon T, Speleman F, Van Vlierberghe P, ABT-199 mediated inhibition of BCL-2 as a novel therapeutic strategy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Blood 124 (2014) 3738–3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Carter BZ, Mak PY, Mu H, Zhou H, Mak DH, Schober W, Leverson JD, Zhang B, Bhatia R, Huang X, Cortes J, Kantarjian H, Konopleva M, Andreeff M, Combined targeting of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase eradicates chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells, Sci. Transl. Med 8 (2016), 355ra117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tian BP, Hua W, Xia LX, Jin Y, Lan F, Lee JJ, Lee NA, Li W, Ying SM, Chen ZH, Shen HH, Exogenous interleukin-17a inhibits eosinophil differentiation and alleviates allergic airway inflammation, Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 52 (2015) 459–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ling D, Park W, Park SJ, Lu Y, Kim KS, Hackett MJ, Kim BH, Yim H, Jeon YS, Na K, Hyeon T, Multifunctional tumor pH-sensitive self-assembled nanoparticles for bimodal imaging and treatment of resistant heterogeneous tumors, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 5647–5655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Weissig V, Torchilin VP, Cationic bolasomes with delocalized charge centers as mitochondria-specific DNA delivery systems, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 49 (2001) 127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kwon HJ, Cha MY, Kim D, Kim DK, Soh M, Shin K, Hyeon T, Mook-Jung I, Mitochondria-targeting ceria nanoparticles as antioxidants for Alzheimer’s disease, ACS Nano 10 (2016) 2860–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang Y, Wei G, Zhang X, Huang X, Zhao J, Guo X, Zhou S, Multistage targeting strategy using magnetic composite nanoparticles for synergism of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy, Small 14 (2018), e1702994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jiang L, Li L, He X, Yi Q, He B, Cao J, Pan W, Gu Z, Overcoming drugresistant lung cancer by paclitaxel loaded dual-functional liposomes with mitochondria targeting and pH-response, Biomaterials 52 (2015) 126–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yang G, Xu L, Xu J, Zhang R, Song G, Chao Y, Feng L, Han F, Dong Z, Li B, Liu Z, Smart nanoreactors for pH-responsive tumor homing, mitochondriatargeting, and enhanced photodynamic-immunotherapy of cancer, Nano Lett. 18 (2018) 2475–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P, Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, Nat. Mater 12 (2013) 991–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ni PY, Ding QX, Fan M, Liao JF, Qian ZY, Luo JC, Li XQ, Luo F, Yang ZM, Wei YQ, Injectable thermosensitive PEG-PCL-PEG hydrogel/acellular bone matrix composite for bone regeneration in cranial defects, Biomaterials 35 (2014) 236–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Xu H, Yao Q, Cai C, Gou J, Zhang Y, Zhong H, Tang X, Amphiphilic poly(- amino acid) based micelles applied to drug delivery: the in vitro and in vivo challenges and the corresponding potential strategies, J. Contr. Release 199 (2015) 84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mokhtarzadeh A, Alibakhshi A, Yaghoobi H, Hashemi M, Hejazi M, Ramezani M, Recent advances on biocompatible and biodegradable nano-particles as gene carriers, Expet Opin. Biol. Ther 16 (2016) 771–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mo R, Sun Q, Xue J, Li N, Li W, Zhang C, Ping Q, Multistage pH-responsive liposomes for mitochondrial-targeted anticancer drug delivery, Adv. Mater 24 (2012) 3659–3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Erle DJ, Sheppard D, The cell biology of asthma, J. Cell Biol 205 (2014) 621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Grainge CL, Maltby S, Gibson PG, Wark PAB, McDonald VM, Targeted therapeutics for severe refractory asthma: monoclonal antibodies, Expet Rev. Clin. Pharmacol 9 (2016) 927–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wynn TA, Type 2 cytokines: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies, Nat. Rev. Immunol 15 (2015) 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chapman DG, Irvin CG, Mechanisms of airway hyper-responsiveness in asthma: the past, present and yet to come, Clin. Exp. Allergy 45 (2015) 706–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ahamed M, Akhtar MJ, Alhadlaq HA, Alrokayan SA, Assessment of the lung toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles: current status, Nanomedicine 10 (2015) 2365–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Silva RM, Doudrick K, Franzi LM, Teesy C, Anderson DS, Wu Z, Mitra S, Vu V, Dutrow G, Evans JE, Westerhoff P, Van Winkle LS, Raabe OG, Pinkerton KE, Instillation versus inhalation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes: exposure-related health effects, clearance, and the role of particle characteristics, ACS Nano 8 (2014) 8911–8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee RJ, Wang S, Low PS, Measurement of endosome pH following folate receptor-mediated endocytosis, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res 1312 (1996) 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.