Significance

Methyl anthranilate (MANT) is widely used in the flavoring and cosmetics industry to give grape scent and flavor. In an effort to replace the conventional petroleum-based synthesis of MANT, we report the direct fermentative production of MANT from glucose in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum strains. A synthetic plant-derived metabolic pathway was introduced and extensive metabolic engineering was performed including fine-tuning key enzyme levels and increasing the availability of precursor and cofactor metabolites. A two-phase extractive cultivation was developed using an extractant solvent to recover MANT in situ, which led to high levels of MANT production. This work demonstrates a promising sustainable alternative to MANT production and presents strategies applicable toward production of other valuable natural compounds.

Keywords: metabolic engineering, Escherichia coli, Corynebacterium glutamicum, methyl anthranilate, two-phase fermentation

Abstract

Methyl anthranilate (MANT) is a widely used compound to give grape scent and flavor, but is currently produced by petroleum-based processes. Here, we report the direct fermentative production of MANT from glucose by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum strains harboring a synthetic plant-derived metabolic pathway. Optimizing the key enzyme anthranilic acid (ANT) methyltransferase1 (AAMT1) expression, increasing the direct precursor ANT supply, and enhancing the intracellular availability and salvage of the cofactor S-adenosyl-l-methionine required by AAMT1, results in improved MANT production in both engineered microorganisms. Furthermore, in situ two-phase extractive fermentation using tributyrin as an extractant is developed to overcome MANT toxicity. Fed-batch cultures of the final engineered E. coli and C. glutamicum strains in two-phase cultivation mode led to the production of 4.47 and 5.74 g/L MANT, respectively, in minimal media containing glucose. The metabolic engineering strategies developed here will be useful for the production of volatile aromatic esters including MANT.

Methyl anthranilate (MANT), which gives grape scent and flavor, has been extensively used in flavoring foods (e.g., candy, chewing gum, soft drinks, and alcoholic drinks, etc.) and drugs (as a flavor enhancer and/or mask). Due to its pleasant aroma, MANT is an important component in perfumes and cosmetics. MANT also has other important industrial applications as a bird and goose repellent for crop protection, as an oxidation inhibitor or a sunscreen agent, and as an intermediate for the synthesis of a wide range of chemicals, dyes, and pharmaceuticals (1).

MANT is a natural metabolite giving the characteristic odor of Concord grapes and occurs also in several essential oils (e.g., neroli, ylang ylang, and jasmine) (1). It has been challenging and economically infeasible to directly extract MANT from these plants due to low yields. Currently, MANT is commercially manufactured by petroleum-based chemical processes, which mainly rely on esterification of anthranilic acid (ANT) with methanol or isatoic anhydride with methanol, using homogeneous acids as catalysts (2). These processes, however, suffer from several disadvantages, for example, the requirement of acid catalysts in large quantities and problems with disposal of these toxic liquid acids after the reaction (2). Moreover, MANT produced by such chemical methods is labeled “artificial flavor,” which does not meet the increasing demand by consumers for natural flavors. Taking another important flavoring agent vanillin as an example, market preference for natural vanillin has led to a far higher price of $1,200–$4,000/kg over $15/kg for artificial vanillin (3). Such a market for natural MANT is also highly desirable, but unfortunately there have so far been no promising methods for preparing MANT from natural sources and/or by natural means. Several enzymatic and microbial whole-cell biotransformation approaches have been attempted for MANT production by esterification of ANT (4) or N-demethylation of N-methyl methyl anthranilate (5). While these biotransformation procedures are considered more natural and ecofriendly compared with chemical synthesis, their actual use is limited due to low yields, long reaction times, and formation of byproducts (5). In addition, the chemical and biotransformation processes mentioned above depend on substrates of petroleum origin. For these reasons, we were motivated to produce MANT through one-step microbial fermentation of renewable feedstocks (e.g., glucose), which would offer 100% biobased natural MANT in an ecofriendly manner.

To our knowledge, there have been rare attempts on the de novo microbial production of MANT, except for two reports nearly 30 y ago describing MANT biosynthesis from simple sugars (i.e., maltose) by the wild-type fungi, Poria cocos (6) and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus (7). Unfortunately, the productivities achieved in these two studies were extremely low (18.7 mg/L MANT produced after 5 d of culture). Also, the underlying biosynthetic mechanisms, including the biosynthesis genes, enzymes, and pathways, in these two fungal species have not been elucidated. Thus, it is a prerequisite to first identify a metabolic pathway leading to the biosynthesis of MANT from simple carbon sources (e.g., glucose), before implementing various metabolic engineering strategies to develop microbial strains capable of efficiently producing MANT based on the reconstituted biosynthetic pathway.

In this study, we report the development of metabolically engineered Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum strains capable of producing MANT directly from glucose through fermentation (Fig. 1). E. coli was initially chosen as a model organism for metabolic engineering toward efficient production of MANT. In addition, C. glutamicum, a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) strain, was also engineered for the production of MANT for its consequent human consumption to give grape flavor and scent in food and cosmetics industries. We applied multiple strategies to produce MANT by optimizing its biosynthesis in both E. coli and C. glutamicum (Fig. 2). First, a synthetic metabolic pathway originated from plant for de novo MANT biosynthesis was constructed in both E. coli and C. glutamicum. Next, MANT production in both engineered organisms was improved through optimization of the key enzyme level, increase of flux to the direct precursor metabolite, increase of the availability of cosubstrate required in MANT synthesis, and establishment of in situ two-phase extractive cultivation process. Finally, two-phase fed-batch cultures of the best E. coli and C. glutamicum strains were performed to demonstrate their potential for large-scale production of MANT from glucose in minimal media.

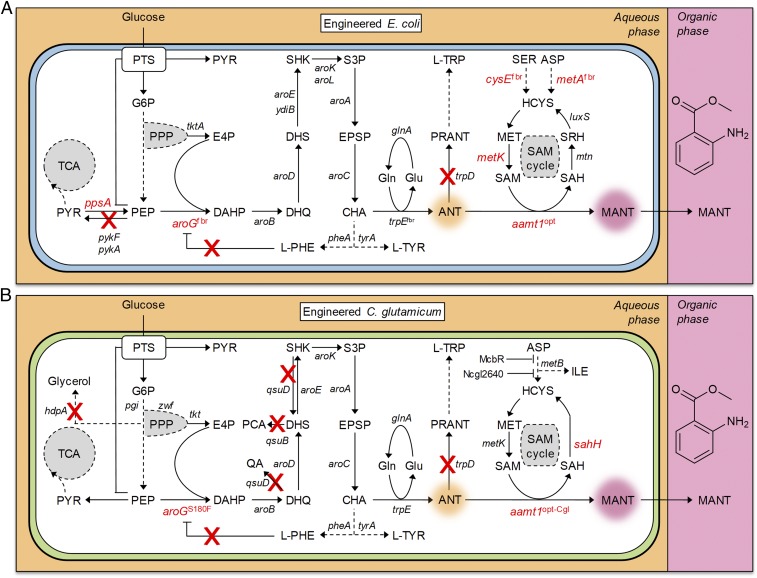

Fig. 1.

The metabolic network related to MANT biosynthesis from glucose in (A) E. coli and (B) C. glutamicum, as well as metabolic engineering strategies employed in this study. Abbreviations: ANT, anthranilate; ASP, l-aspartate; CHA, chorismate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate; DHQ, 3-dehydroquinate; DHS, 3-dehydroshikimate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; EPSP, 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimate 3-phosphate; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; HCYS, l-homocysteine; ILE, isoleucine; l-PHE, l-phenylalanine; l-TRP, l-tryptophan; l-TYR, l-tyrosine; MANT, methyl anthranilate; MET, l-methionine; PCA, protocatechuate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; PRANT, N-(5-phosphoribosyl)-anthranilate; PTS, phosphotransferase system; PYR, pyruvate; QA, quinate; S3P, shikimate-3-phosphate; SAH, S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine; SAM, S-adenosyl-l-methionine; SER, l-serine; SHK, shikimate; SRH, S-ribosyl-l-homocysteine; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle. Genes that encode enzymes: ppsA, PEP synthetase; pykF, PYR kinase I; pykA, PYR kinase II; tktA, transketolase I; aroGfbr, feedback-inhibition resistant mutant of DAHP synthase; aroB, DHQ synthase; aroD, DHQ dehydratase; aroE and ydiB, SHK dehydrogenase; aroK, SHK kinase I; aroL, SHK kinase II; aroA, 3-phosphoshikimate-1-carboxyvinyltransferase; aroC, CHA synthase; tyrA and pheA, TyrA and PheA subunits of CHA mutase, respectively; trpEfbr and trpD, ANT synthase component I (feedback inhibition-resistant mutant) and II, respectively; glnA, Gln synthetase; cysEfbr, SER acetyltransferase (feedback inhibition-resistant mutant); metAfbr, homoserine O-succinyltransferase (feedback inhibition-resistant mutant); luxS, S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase; mtn, 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase; metK, MET adenosyltransferase; aamt1, ANT methyltransferase1; pgi, G6P isomerase; zwf, G6P 1-dehydrogenase; tkt, transketolase; hdpA, dihydroxyacetone phosphate phosphatase; qsuB, DHS dehydratase; qsuD, QA/SHK dehydrogenase; metB, cystathionine-γ-synthase; sahH, SAH hydrolase; mcbR and Ncgl2640, transcriptional regulator. The solid arrows indicate single metabolic reaction, and the dashed arrows indicate multiple reactions. Overexpressed genes are marked in red, and red X indicates gene deletions. In situ two-phase extractive cultivation process is schematically illustrated, in which the MANT produced in the aqueous phase is extracted into the organic phase.

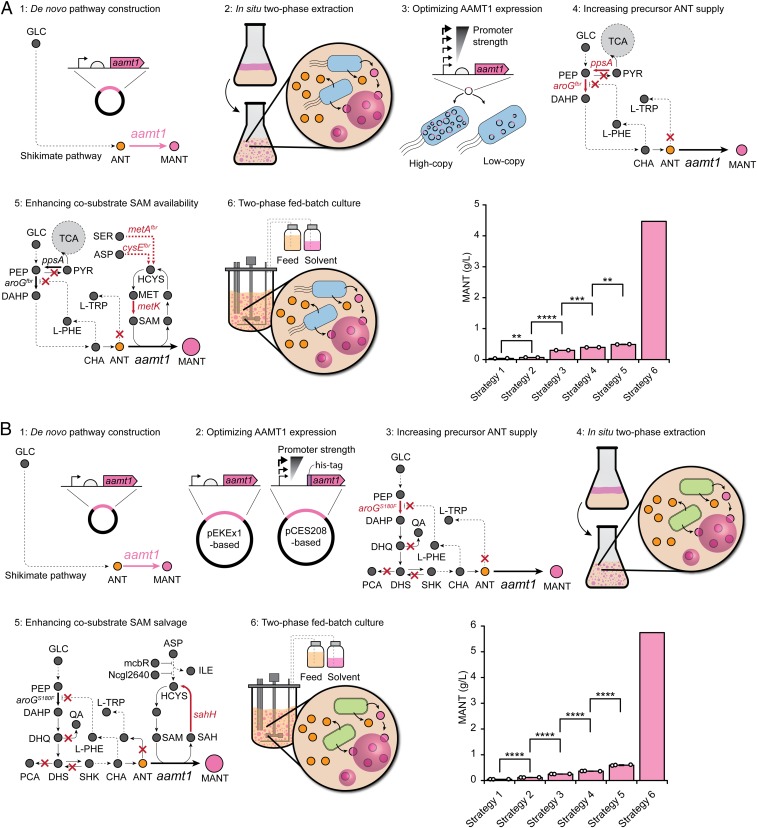

Fig. 2.

The overview of engineering strategies to optimize MANT production in E. coli and C. glutamicum. (A) Engineering strategies applied to produce MANT from glucose in E. coli, which include (1) initial construction of the de novo MANT biosynthesis pathway, (2) establishing an in situ two-phase extractive cultivation process to address MANT toxicity, (3) optimizing the key enzyme AAMT1 expression, (4) increasing the precursor ANT supply by metabolic engineering, (5) enhancing the availability of cosubstrate SAM required by the AAMT1-catalyzed reaction, and (6) in situ two-phase extractive fed-batch culture for bioreactor-scale MANT production. The successive increase in MANT titer with each strategy is also illustrated. The pink bars represent the concentration of MANT (in grams per liter). Values and error bars represent means and SDs of biological duplicates. The white circles represent individual data points. Error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 2). The P values were computed by two-tailed Student’s t test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (B) Engineering strategies to produce MANT from glucose using C. glutamicum, which include (1) initial construction of the de novo MANT biosynthesis pathway, (2) optimizing the key enzyme AAMT1 expression, (3) increasing precursor ANT supply by metabolic engineering, (4) establishing an in situ two-phase extractive cultivation process to address MANT toxicity, (5) salvaging the availability of cosubstrate SAM required by the AAMT1-catalyzed reaction, and (6) in situ two-phase extractive fed-batch culture for bioreactor-scale MANT production. The successive increase in MANT titer with each strategy is also illustrated. The pink bars represent the concentration of MANT (in grams per liter). Values and error bars represent means and SDs of biological triplicates. The white circles represent individual data points. Error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3). The P values were computed by two-tailed Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001).

Results and Discussion

Constructing a MANT Biosynthetic Pathway in E. coli.

Due to the lack of knowledge on the MANT metabolism in the two fungal species described above, we focused on the mechanism of MANT biosynthesis in plants to identify a MANT biosynthetic pathway. Intriguingly, literature survey (8) suggested two different MANT biosynthetic mechanisms present in plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Both routes share the same precursor metabolite ANT, which is derived from the l-tryptophan (l-TRP) biosynthesis pathway in plants. For further conversion of ANT to MANT, one route involves two reaction steps: CoA activation catalyzed by anthranilate-CoA ligase followed by acyl transfer by anthraniloyl-CoA:methanol acyltransferase using CoA, ATP, and methanol as cosubstrates. The other route uses a single-step conversion of ANT to MANT catalyzed by S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase. In this study, we chose the latter route as it is a simpler reaction requiring less cofactors, and more importantly, it does not require toxic methanol. Three such SAM-dependent methyltransferases have previously been identified in the plant maize (Zea mays) (8). Among them, the one called anthranilic acid methyltransferase1 (AAMT1; encoded by aamt1) was selected in this work as it was characterized to be the most active for MANT formation in maize (8).

Based on the selected SAM-dependent methylation-mediated MANT synthesis pathway, we expressed AAMT1 in an ANT-overproducing E. coli W3110 trpD9923 strain (9) (SI Appendix, Table S1) by introducing pTrcT that contained an E. coli codon-optimized version of aamt1 gene, designated as aamt1opt (SI Appendix, Table S2), under the control of trc promoter. The successful expression of AAMT1 in the recombinant W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTrcT was confirmed by SDS/PAGE (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). In a shake-flask culture using glucose as a sole carbon source, the W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTrcT successfully produced 35.8 ± 3.0 mg/L MANT (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), along with the accumulation of 215.5 ± 7.5 mg/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). No MANT production was detected in the wild-type W3110 trpD9923, although it produced a higher amount of ANT (305.4 ± 2.5 mg/L) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

MANT Toxicity to E. coli.

After the construction of a functional MANT biosynthesis pathway in E. coli, we next evaluated the toxicity of MANT to E. coli cells before further experiments. Exposing the wild-type E. coli W3110 cells to different concentrations of MANT (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, and 1.0 g/L) indicated a dose-dependent growth inhibition by MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In the presence of 0.3 g/L MANT, the final optical density at the wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) was only a half of that obtained with the control experiment without MANT exposure (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). When exposed in 1.0 g/L MANT, E. coli cell growth was completely inhibited (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Designing an in Situ Two-Phase Extractive Culture Process.

To circumvent this product toxicity limitation, a two-phase (aqueous/organic) cultivation system was designed, where MANT is extracted in situ from the culture medium using an organic solvent (Fig. 1). Tributyrin is one organic solvent nontoxic to microorganisms including E. coli (10) and is also used in the food industry, which can facilitate downstream purification processes for preparing food-grade MANT. Tributyrin was observed to extract MANT very efficiently as evidenced by its high partition coefficient (420.1 ± 7.6) between aqueous medium phase and tributyrin phase (SI Appendix, Table S3). Tributyrin could also extract ANT from the aqueous phase, but to a far lesser extent compared with that for MANT; the partition coefficients for ANT were 4.7 ± 0.2 and 0.1 ± 0.0 at pH 5.0 and 7.0, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S3). The low partitioning of ANT into tributyrin phase can be explained by its pKa value of 2.14.

Using this two-phase system in shake-flask cultivation (a 5:1 aqueous-to-organic phase ratio) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTrcT produced 65.6 ± 0.4 mg/L MANT (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B; see SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Materials and Methods for the calculation of MANT concentration), which was 83.2% higher than that obtained in the single-phase culture. Also, almost all of the produced MANT was extracted into the solvent phase, while MANT was undetectable in the aqueous phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).

Optimizing AAMT1 Expression for MANT Production in E. coli.

Following the establishment of in situ two-phase extractive cultivation process, we set out to optimize MANT production by manipulating expression of the key enzyme AAMT1 (Fig. 1A). Expression levels of AAMT1 were varied by expressing the aamt1opt gene, either on the medium-copy pTrc99A vector under a set of six synthetic constitutive promoters with different strengths (BBa_J23117, BBa_J23114, BBa_J23105, BBa_J23118, BBa_J23101, and BBa_J23100) (SI Appendix, Table S4), or on the low-copy pTac15K vector under the same set of synthetic promoters as well as the stronger isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible tac promoter (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). When these AAMT1 constructs, pTrc99A-series or pTac15K-series, were introduced to W3110 trpD9923 strain and tested in two-phase flask culture, a clearly positive correlation of MANT production with the strengths of the promoters employed within the same vector series was observed, while ANT accumulation was negatively correlated (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Also, it was found that under each of the six synthetic promoters, AAMT1 expressed on the medium-copy pTrc99A vector enabled higher MANT production compared with those on the low-copy pTac15K (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Among these recombinant strains, W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTacT (aamt1opt expressed on pTac15K under tac promoter) produced MANT to the highest titer of 297.3 ± 0.7 mg/L (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), while accumulating ANT to the least amount of 117.1 ± 2.2 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Based on these results, we further cloned aamt1opt on pTac15K under T5 promoter with stronger strength than tac promoter (11), which however resulted in less MANT production (219.1 ± 10.9 mg/L) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Increasing ANT Supply for MANT Production in E. coli.

Next, we aimed at increasing intracellular flux to the direct precursor ANT to further improve MANT production. ANT is a native metabolite in l-TRP biosynthesis pathway in E. coli (Fig. 1A). Previous studies on engineering E. coli for ANT overproduction have suggested several promising strategies for increasing ANT production (12, 13). First, a feedback inhibition-resistant 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase (encoded by aroGfbr) catalyzing the condensation of erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) was expressed, by constructing pTrcGfbr (aroGfbr cloned on medium-copy pTrc99A under the strong trc promoter) and pBBR1Gfbr (aroGfbr cloned on low-copy pBBR1MCS under the less strong lac promoter). W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr produced 731.7 ± 7.4 mg/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), which was 2.3- and 1.4-fold higher than those obtained with W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTrcGfbr (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) and wild-type W3110 trpD9923 strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), respectively. Second, we attempted to increase the availability of two key precursors E4P and PEP of the aromatic amino acid pathway for improving ANT production. To increase E4P, the tktA gene encoding transketolase I was overexpressed by constructing pBBR1Gfbr-A. W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A produced 760.4 ± 12.5 mg/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), which was only slightly higher than that obtained with W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr. To increase PEP, several different strains were constructed: ZWA1 (trc promoter exchange for ppsA overexpression), ZWA2 (pykF knockout), ZWA3 (pykF and pykA double-knockout), and ZWA4 (trc promoter exchange for ppsA overexpression and pykF knockout). However, flask cultures of these four engineered strains each harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A showed no further increase in ANT titer (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). The specific ANT production per OD600 of ZWA1, ZWA2, ZWA3, ZWA4, and the parental strain (W3110 trpD9923) harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A was calculated to be 113.4, 114.6, 117.0, 112.0, and 122.7 mg/L OD600−1, respectively. Thus, ZWA4 strain was chosen for further engineering. Third, two additional overexpression targets involved in l-TRP pathway (Fig. 1A), aroL (encoding shikimate kinase II) (14) and trpEfbr (encoding a feedback inhibition-resistant ANT synthase) (15), were examined by constructing pTacLEfbr. ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacLEfbr produced 820.5 ± 30.3 mg/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), which was 8.7% higher than that obtained with ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A.

The above-engineered strains overproducing ANT were combined with AAMT1 to produce MANT. To this end, three combination strains were constructed: ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and LEfbr-pTacT, ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacT, and ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr and pTacT. Two-phase flask cultures of these engineered strains showed that ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacT produced the highest MANT titer (392.0 ± 1.7 mg/L) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B).

Enhancing SAM Availability for MANT Production in E. coli.

Apart from MANT production in the strains described above, ANT was also formed as a byproduct. For example, ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacT, which so far produced the highest MANT titer (392.0 ± 1.7 mg/L), accumulated 416.4 ± 7.8 mg/L ANT at the same time (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Such a high-level accumulation of ANT indicated a potential bottleneck present in the conversion of ANT to MANT. One possible reason was thought to be limited availability of the cosubstrate SAM required by the AAMT1 reaction. The following strategies were applied to increase SAM availability by optimizing its biosynthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) and consequently to further increase MANT production while reducing ANT formation. First, the metAfbr gene encoding feedback inhibition-resistant homoserine succinyltransferase and cysEfbr encoding l-serine O-acetyltransferase (16) were overexpressed for enhancing SAM biosynthesis (Fig. 1A). As a result, ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT produced MANT to a 6.8% higher concentration of 388.3 ± 6.0 mg/L and ANT to a 16.9% lower concentration of 346.3 ± 3.3 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) than those obtained with the parental strain ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr and pTacT. Next, the metK gene encoding SAM synthetase was also overexpressed by constructing pTacTK. ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacTK produced MANT to an 8.4% higher concentration of 424.8 ± 5.0 mg/L and ANT to a 16.4% lower concentration of 348.3 ± 7.8 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) than those obtained with ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacT. These three overexpression targets were combined to construct ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacTK, which produced ANT to the lowest concentration of 274.2 ± 8.4 mg/L. However, MANT titer was intriguingly decreased to 404.3 ± 5.4 mg/L compared with the best strain (ZWA4 harboring pBBR1Gfbr-A and pTacTK) so far (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Thus, l-methionine (MET), the direct precursor to SAM synthesis, was further supplemented to see whether MANT production can be increased; this is thought to work because the metAfbr and cysEfbr genes we employed encode feedback inhibition-resistant enzymes in MET biosynthetic pathway. The three strains constructed above were cultured again in two-phase flasks with addition of 20 mM MET. As a result, the highest MANT titer of 489.0 ± 7.4 mg/L was obtained in ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8), which was 25.9% higher than that without MET supplementation. This MANT titer corresponded to 12.7-fold increase compared with that obtained with the initial W3110 trpD9923 strain harboring pTrcT in single-phase flask culture without MET supplementation. This strain still accumulated 346.7 ± 4.2 mg/L ANT. Also, ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacTK produced a similarly high level of MANT (486.8 ± 4.8 mg/L) to that achieved with ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT, but accumulated much less ANT (258.9 ± 7.6 mg/L) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Thus, these two strains were selected and further evaluated in fed-batch cultures.

MANT Production in E. coli Two-Phase Fed-Batch Fermentations.

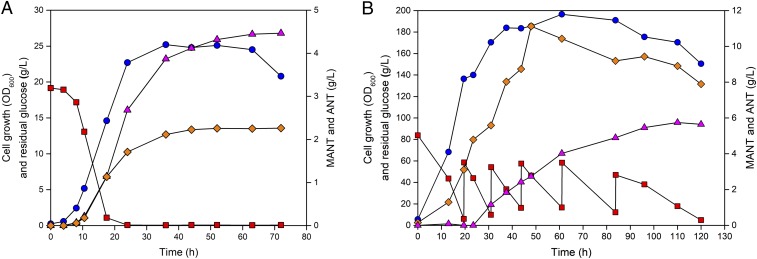

Fed-batch cultures of the two engineered E. coli strains above were performed in two-phase mode for in situ extraction of MANT in a glucose minimal medium. The pH-stat feeding strategy was employed for nutrient feeding. Ammonium sulfate was added to provide additional nitrogen source. As it was found beneficial, MET (20 mM) was supplemented to enhance SAM availability. Under these conditions, ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacTK produced 4.12 g/L MANT and 3.74 g/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), while ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT produced 4.47 g/L MANT (Figs. 2 and 3A) and 2.26 g/L ANT (Fig. 3A). For the latter strain, the yield and productivity of MANT were 0.045 g/g glucose and 0.062 g⋅L−1⋅h−1, respectively.

Fig. 3.

In situ two-phase extractive fed-batch culture profiles of (A) the engineered E. coli ZWA4 strain harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT and (B) the engineered C. glutamicum YTM8 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH under the condition of elevated DO level (50% air saturation). Symbols: blue circle, cell growth (OD600); red rectangle, residual glucose concentration (in grams per liter); orange diamond, ANT concentration (in grams per liter); magenta triangle, MANT concentration (in grams per liter).

Selecting C. glutamicum Chassis for Food-Grade MANT Production.

Having accomplished the proof-of-concept fermentative production of MANT from glucose by metabolically engineered E. coli, we pursued to produce food-grade MANT by using other industrial GRAS microbial strains as MANT is mainly applied in food and cosmetic industries. Two such bacterial hosts, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (Gram-negative) (17) and C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (Gram-positive) (18), were examined for their potential to produce MANT by comparing their tolerance levels to MANT toxicity. The toxicity test showed that both strains had the growth profiles exhibiting concentration-dependent inhibition by MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), similar to E. coli. However, P. putida KT2440 cells could not grow in the presence of 1.0 g/L MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). On the other hand, complete growth inhibition of C. glutamicum was observed when 2.0 g/L MANT was applied (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). These results suggest that C. glutamicum has a higher tolerance to MANT compared with P. putida KT2440 and also E. coli. Thus, C. glutamicum was selected as the host for food-grade MANT production (Fig. 1B). Similar metabolic engineering strategies were applied to optimize MANT production in C. glutamicum (Fig. 2B).

Tuning AAMT1 Levels for MANT Production in C. glutamicum.

To construct MANT synthesis pathway, we expressed the aamt1opt gene in the wild-type C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 strain and optimized its expression by constructing the following AAMT1 expression plasmids (SI Appendix, Table S5): pEKT (aamt1opt cloned on pEKEx1 vector under tac promoter), pL10T, pI16T and pH36T (aamt1opt cloned on pCES208 vector under L10, I16 and H36 promoters), pL10HT, pI16HT and pH36HT (aamt1opt cloned on pCES208 vector under L10, I16, and H36 promoters with a N-terminal 6xHis-tag) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). These promoters (tac, L10, I16, and H36) have been reported to have different strengths of gene expression (19), and the use of a His-tag was previously demonstrated to enhance gene expression in C. glutamicum (20). C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 strains harboring these plasmids were tested in single-phase shake-flask cultures supplemented with 0.8 g/L ANT. As a result, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 strain harboring pH36HT produced MANT to the highest titer of 97.2 ± 8.6 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). No MANT was detected in the wild-type C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B).

Plasmid pH36HT was thus introduced to C. glutamicum YTM1 strain (SI Appendix, Table S5), in which the trpD gene was disrupted to block the l-TRP biosynthesis pathway in C. glutamicum after ANT (Fig. 1B). In flask culture without external ANT feeding and using glucose as a sole carbon source, YTM1 strain harboring pH36HT produced 45.3 ± 1.6 mg/L MANT (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S12) as well as 408.2 ± 4.2 mg/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Furthermore, we tested a C. glutamicum codon-optimized version of aamt1 gene, designated as aamt1opt-Cgl (SI Appendix, Table S6), by cloning it on pCES208 under H36 promoter with a N-terminal 6×His-tag in the same configuration as for pH36HT, generating pH36HTc. Flask culture of YTM1 strain harboring pH36HTc produced MANT to a 1.6-fold higher concentration of 117.1 ± 2.0 mg/L (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S12) and ANT to a 55.0% lower concentration of 183.8 ± 3.1 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), compared with those obtained by YTM1 strain harboring pH36HT. We further deleted the qsuB and qsuD genes in YTM1 strain, which are involved in competitive pathways toward protocatechuate and quinate synthesis, respectively, in C. glutamicum (Fig. 1B), generating YTM2 strain. As a result, YTM2 harboring pH36HTc produced MANT to an increased titer of 130.4 ± 0.8 mg/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) compared with the parental strain (YTM1 harboring pH36HTc).

Increasing ANT Supply for MANT Production in C. glutamicum.

Next, further metabolic engineering approaches were taken to increase the level of ANT and consequently to improve MANT production in C. glutamicum. Although reported in E. coli (12, 13) and P. putida (21), ANT overproduction has never been explored in C. glutamicum. To increase ANT production in C. glutamicum, several target genes were manipulated: e.g., aroG, aroB, and aroK known as potential limiting steps in the shikimate pathway (Fig. 2B), and pgi, zwf, tkt, opcA, pgl, and tal known to enhance flux through the pentose phosphate pathway (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), which were target genes similarly manipulated for the overproduction of shikimic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, l-ornithine, and l-arginine in C. glutamicum (22–25). To this end, the following strains were constructed: YTM3 (with the native promoters of aroK and aroB replaced with the strong constitutive sod promoter in YTM2 strain), YTM4 (with the start codon of pgi changed from ATG to GTG for down-regulation and of zwf changed from GTG to ATG for up-regulation in YTM3 strain), YTM5 (with the native promoter of tkt replaced with sod promoter in YTM4 strain), as well as plasmid pEKG (overexpressing aroGS180F encoding a feedback-resistant DAHP synthase). In flask cultures, YTM3 strain produced 15.7% less ANT than did the parental YTM2 strain; YTM3 strain harboring pEKG produced 4.8-fold more ANT than did YTM3 strain without pEKG; YTM4 and YTM5 strains harboring pEKG produced similar levels of ANT to that obtained with the parental YTM3 strain harboring pEKG (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A). These results collectively suggested that only aroGS180F overexpression by pEKG could increase ANT production. Thus, aroGS180F was overexpressed in the best MANT producer strain YTM2 harboring pH36HTc. Since pH36HTc and pEKG harbor the same antibiotic (kanamycin) marker, we changed the antibiotic marker of pH36HTc from kanamycin to spectinomycin/streptomycin, generating pSH36HTc. Flask culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc produced 131.1 ± 9.0 mg/L MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B), which was almost the same as that obtained with YTM2 harboring pH36HTc (130.4 ± 0.8 mg/L). Plasmid pEKG was then successfully introduced to YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc, which produced MANT to a 91.6% higher concentration of 251.2 ± 2.5 mg/L (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S14B) and ANT to a 13.8-fold higher concentration of 3.38 ± 0.07 g/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B), compared with those obtained with YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc alone. Up to this point, all flask cultures of C. glutamicum strains were conducted in single-phase cultivation mode. Thus, two-phase extractive flask culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG was performed, which produced MANT to a 44.9% higher concentration of 364.1 ± 5.4 mg/L (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S14B) and ANT to a 21.0% lower concentration of 2.67 ± 0.03 g/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B), compared with those obtained in single-phase culture.

Enhancing SAM Salvage for MANT Production in C. glutamicum.

To further improve MANT production in C. glutamicum, the cosubstrate SAM availability was also considered. SAM overproduction in C. glutamicum has been reported in a previous study (26), which focused on enhancing the flux to SAM biosynthesis (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Several effective strategies in that report were selected and applied for SAM production in this study. First, the metK gene encoding methionine adenosyltransferase was overexpressed by constructing pEKGK. As a result, YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGK in two-phase flask culture produced 377.0 ± 16.2 mg/L MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), which was only slightly higher than that obtained with YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG. Next, the mcbR and Ncgl2640 genes encoding transcriptional regulators involved in regulation of MET biosynthesis were deleted in YTM2 strain, generating YTM6. Furthermore, the metB gene encoding cystathionine-γ-synthase involved in competitive synthesis of l-isoleucine was deleted in YTM6 strain, generating YTM7. However, two-phase flask cultures of YTM6 and YTM7 strains harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG showed severely retarded cell growth, and consequently produced 80.0 ± 4.2 and 72.3 ± 5.5 mg/L MANT, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), which were far lower than that obtained with YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG. In addition to genetic engineering for SAM synthesis, we directly supplemented the SAM precursor MET (10 mM) in two-phase flask culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG as it had increased MANT titer in E. coli. Unfortunately, the direct supplementation of MET resulted in the production of 326.8 ± 3.9 mg/L MANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), lower than that without MET supplementation. From these results, it was speculated that SAM availability might not be a limiting factor for MANT production in C. glutamicum.

Thus, a different strategy of engineering the SAM salvage pathway (Fig. 1B) was applied for recycling the SAM reaction product S-ribosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) back to SAM synthesis pathway catalyzed by SAH hydrolase (encoded by sahH) (27). The sahH gene was overexpressed from pEKGH. To our pleasant surprise, two-phase flask culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH produced MANT to a 63.9% higher concentration of 596.9 ± 16.7 mg/L (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S16) and ANT to a 5.2% lower concentration of 2.53 ± 0.01 g/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), compared with those obtained with YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKG. This MANT titer is 12.3-fold higher than that obtained with the initial YTM1 strain harboring pH36HT in single-phase flask culture.

MANT Production in C. glutamicum Two-Phase Fed-Batch Fermentations.

Since C. glutamicum showed higher tolerance to MANT toxicity, we first performed a single-phase fed-batch culture using the best C. glutamicum MANT producer strain YTM2 harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH in glucose minimal medium without MET supplementation, which led to production of 1.70 g/L MANT and 14.11 g/L ANT (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). Next, in situ two-phase extractive fed-batch culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH under the same settings was performed, which produced MANT to a 1.36-fold higher concentration of 4.01 g/L and ANT to an 86.1% lower concentration of 1.96 g/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S18), compared with those obtained in single-phase fermentation. In this two-phase fermentation, succinic acid was also accumulated to 10.06 g/L. Compared with single-phase fermentation, the two-phase fermentation resulted in an emulsion-like environment, which might interfere with oxygen transferred to the cells. It was hypothesized that the high succinic acid accumulation was due to oxygen limitation. Thus, the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was increased by setting the control DO value from 30 to 50% of air saturation and also by changing agitation speed from the fixed at 600 rpm to automatic increase from 600 to 1,000 rpm according to DO. By increasing the DO level, the two-phase fed-batch culture of YTM2 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH produced MANT to a 30.9% higher concentration of 5.25 g/L at the 110-h mark and ANT to a 2.0-fold higher concentration of 5.90 g/L (SI Appendix, Fig. S19), with succinic acid reduced to 5.09 g/L. Glycerol formation was also observed in the fermentation broth, and thus the hdpA gene involved in glycerol formation pathway was also deleted (SI Appendix, Fig. S20) (22, 23) in YTM2 strain, generating YTM8. As a result, two-phase fed-batch culture of YTM8 strain harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH produced MANT to a 9.3% higher concentration of 5.74 g/L at 110 h (Figs. 2B and 3B) and ANT to a 33.7% higher concentration of 7.89 g/L (Fig. 3B). The resultant yield and productivity of MANT were 0.020 g/g glucose and 0.052 g⋅L−1⋅h−1, respectively.

ANT Production.

Although it is not the major subject of this study, ANT is also an important industrial platform chemical with many applications (21), and its biobased production is an active research subject (12, 13, 21). During the two-phase extractive fermentation at neutral pH performed in this study, it is noticeable that all of the MANT was extracted into the tributyrin phase, while almost all ANT (e.g., 96.9% in the case of fed-batch culture of E. coli ZWA4 harboring pBBR1GfbrAfbrEfbr and pTacT, 98.4% in the case of fed-batch culture of C. glutamicum YTM8 harboring pSH36HTc and pEKGH) was retained in aqueous phase. This is particularly beneficial for downstream processes to purify MANT and also ANT from the fermentation broth. From a process engineering perspective, this could be regarded as a coproduction of both MANT and ANT. To explore the capacity for sole ANT production, we further performed a single-phase fed-batch culture using one of the engineered ANT overproducers developed in this study, i.e., C. glutamicum YTM5 strain harboring pEKG. The single-phase fermentation of this strain led to the production of 26.40 g/L ANT at 84 h in glucose minimal medium (SI Appendix, Fig. S21), representing not only the production of this compound by C. glutamicum, but also the highest ANT production titer reported in any microbial host to date. On the other hand, the residual amount of this precursor metabolite indicates that there is still some room for improvement of MANT production. One promising strategy would be to engineer the ANT methyltransferase by enzyme evolution for greater catalytic activity, thereby more efficiently converting the residual ANT to MANT.

In summary, we report the development of metabolically engineered E. coli and C. glutamicum strains capable of producing MANT by direct fermentation in minimal media containing glucose as a sole carbon source. A synthetic metabolic pathway for MANT biosynthesis was constructed in both E. coli and C. glutamicum, and MANT production was optimized by tuning the key enzyme AAMT1 expression, increasing flux toward precursor ANT, and increasing availability (in E. coli) and salvage (C. glutamicum) of cosubstrate SAM required by the AAMT1 reaction. In situ two-phase extractive fed-batch fermentation process was also developed for MANT production by the engineered E. coli and C. glutamicum, which led to production of 4.47 and 5.74 g/L MANT from glucose, respectively. These titers are significantly high for natural compounds produced by microbial fermentation, as most natural compounds from engineered microbes are produced at levels of milligrams or micrograms per liter (28). Also, all fermentations described in this study were performed in minimal media, which further help decrease operation and separation costs (29). This methanol-free biobased production of MANT paves the way toward a sustainable, consumer-friendly process to produce MANT as a “natural” flavoring agent, which for the past 100 y has only been produced industrially through chemical synthesis. The metabolic engineering strategies and methodologies described and the engineered microbial systems established here will contribute to the development of engineered strains for the sustainable production of other chemicals with similar properties and characteristics as MANT.

Materials and Methods

All of the materials and methods conducted in this study are detailed in SI Appendix, Supplementary Information Materials and Methods, including bacterial strains and media, construction of E. coli expression plasmids, E. coli genome manipulation, construction of C. glutamicum expression plasmids, construction of CRISPR-based recombineering plasmids for gene knockout in C. glutamicum, construction of genetic engineering plasmids for promoter exchange and for further gene knockout in C. glutamicum YTM2, C. glutamicum genome manipulation, MANT toxicity test, SDS/PAGE analysis, determination of partition coefficients, cultivation condition, and analytical procedures. The data supporting the findings of this study are available in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Ki Jun Jeong for generously providing us with plasmids pCES-L10-M18, pCES-I16-M18, and pCES-H36-M18 for cloning in this study. We also thank Tae Hee Han for providing plasmid pSY06b. This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (Grants NRF-2012M1A2A2026556 and NRF-2012M1A2A2026557).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1903875116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wang J, De Luca V (2005) The biosynthesis and regulation of biosynthesis of Concord grape fruit esters, including “foxy” methylanthranilate. Plant J 44:606–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadav GD, Krishnan MS (1998) An ecofriendly catalytic route for the preparation of perfumery grade methyl anthranilate from anthranilic acid and methanol. Org Process Res Dev 2:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walton NJ, Mayer MJ, Narbad A (2003) Vanillin. Phytochemistry 63:505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittleson JR, Pantaleone DP (1994) US Patent 5437991.

- 5.Taupp M, Harmsen D, Heckel F, Schreier P (2005) Production of natural methyl anthranilate by microbial N-demethylation of N-methyl methyl anthranilate by the topsoil-isolated bacterium Bacillus megaterium. J Agric Food Chem 53:9586–9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger RG, Drawert F, Hadrich S (1988) Microbial sources of flavour compounds. In Bioflavour ’87, ed Schreier P (Walter de Gruyter, Berlin).

- 7.Gross B, et al. (1990) Production of methylanthranilate by the basidiomycete Pycnoporus cinnabarinus (Karst.). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 34:387–391. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köllner TG, et al. (2010) Herbivore-induced SABATH methyltransferases of maize that methylate anthranilic acid using S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Plant Physiol 153:1795–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanofsky C, Horn V, Bonner M, Stasiowski S (1971) Polarity and enzyme functions in mutants of the first three genes of the tryptophan operon of Escherichia coli. Genetics 69:409–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim B, Park H, Na D, Lee SY (2014) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of phenol from glucose. Biotechnol J 9:621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ajikumar PK, et al. (2010) Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science 330:70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balderas-Hernández VE, et al. (2009) Metabolic engineering for improving anthranilate synthesis from glucose in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 8:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noda S, Shirai T, Oyama S, Kondo A (2016) Metabolic design of a platform Escherichia coli strain producing various chorismate derivatives. Metab Eng 33:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dell KA, Frost JW (1993) Identification and removal of impediments to biocatalytic synthesis of aromatics from d-glucose: Rate-limiting enzymes in the common pathway of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 115:11581–11589. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu P, Yang F, Kang J, Wang Q, Qi Q (2012) One-step of tryptophan attenuator inactivation and promoter swapping to improve the production of l-tryptophan in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact 11:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunjapur AM, Hyun JC, Prather KLJ (2016) Deregulation of S-adenosylmethionine biosynthesis and regeneration improves methylation in the E. coli de novo vanillin biosynthesis pathway. Microb Cell Fact 15:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeschcke A, Thies S (2015) Pseudomonas putida—a versatile host for the production of natural products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:6197–6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker J, Wittmann C (2012) Bio-based production of chemicals, materials and fuels—Corynebacterium glutamicum as versatile cell factory. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yim SS, An SJ, Kang M, Lee J, Jeong KJ (2013) Isolation of fully synthetic promoters for high-level gene expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol Bioeng 110:2959–2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JH, et al. (2016) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for enhanced production of 5-aminovaleric acid. Microb Cell Fact 15:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuepper J, et al. (2015) Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 to produce anthranilate from glucose. Front Microbiol 6:1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kogure T, Kubota T, Suda M, Hiraga K, Inui M (2016) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for shikimate overproduction by growth-arrested cell reaction. Metab Eng 38:204–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitade Y, Hashimoto R, Suda M, Hiraga K, Inui M (2018) Production of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid by an aerobic growth-arrested bioprocess using metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02587-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SY, Lee J, Lee SY (2015) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of l-ornithine. Biotechnol Bioeng 112:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SH, et al. (2014) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-arginine production. Nat Commun 5:4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han G, Hu X, Qin T, Li Y, Wang X (2016) Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC13032 to produce S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Enzyme Microb Technol 83:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozada-Ramírez JD, Martínez-Martínez I, Sánchez-Ferrer A, García-Carmona F (2008) S-Adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase from Corynebacterium glutamicum: Cloning, overexpression, purification, and biochemical characterization. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 15:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park SY, Yang D, Ha SH, Lee SY (2018) Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of natural compounds. Adv Biosyst 2:1700190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY, Kim HU (2015) Systems strategies for developing industrial microbial strains. Nat Biotechnol 33:1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.