Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to estimate the association between self-esteem and subsequent self-rated health during college years, taking into account a wide range of potential confounders.

Design

Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting

The French i-Share cohort.

Participants

The sample consisted of 1011 college students.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The association between self-esteem and later self-rated health was evaluated using multivariate modelling.

Data regarding self-rated health, global self-esteem and demographic, educational, social, behavioural, environmental and financial characteristics were collected through an internet-based questionnaire.

Results

The 1011 participants had a median age of 21.9 years and 79% (795/1011) were females. Self-rated health was assessed a median of 8 months after the self-esteem measurement. Twenty per cent of the students declared average to very poor health (203/1011). Students with higher levels of self-esteem were more likely to declare good or very good self-rated health (adjusted OR=1.40, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.72, p value=0.001). Other factors associated with good or very good self-rated health were low body mass index, a comfortable financial situation during childhood and three personality traits (low persistence and harm avoidance and high cooperativeness).

Conclusions

This study offers novel findings on the impact of self-esteem on self-rated health among college students. Interventions targeting self-esteem should be experimented during university years in order to improve health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study is based on a prospective design with a large number of participants.

A broad adjustment was made for confounders to estimate unbiased association.

This study investigates self-rated health among college students, a population that has received less attention in the literature.

Participants were volunteers in the i-Share project, which may have caused a sampling bias. Extrapolation to other student populations may be limited.

Reverse causation between self-esteem and self-rated health may exist and could not be investigated with our design.

Introduction

Self-rated health is considered to be a relevant indicator of general health. The high validity, reliability and predictive power of self-rated health make it one of the best predictors of objective health problems (including mortality) and healthcare utilisation.1–5 Collection of self-rated health is recommended by the WHO as a standard and cost-effective measure in health surveys.6–9

Associations between self-rated health and mortality persist even after objective health adjustment, suggesting that self-rated health could constitute an inclusive and universal predictor alongside clinical examination, medical records or self-reports of medical conditions.10

Determinants of self-rated health problems have attracted interdisciplinary interest. Several studies have investigated demographic, educational, social, behavioural, environmental and financial determinants.11 In addition, a few studies have emphasised the associations between psychosocial resources and self-rated health assessment.12 13 However, there are important limitations in the literature that should be underlined.

First, despite recent research, psychosocial resources have been insufficiently investigated in the literature.13 Among individual characteristics, the impact of self-esteem (ie, the overall aggregated opinion of oneself at any one time, as defined by Rosenberg) on the rating of one’s health remains poorly understood. Yet, it should be noted that self-esteem is a potentially modifiable factor. If self-esteem is predictive of self-rated health independently of other psychosocial confounders, it could represent a specific target for preventive interventions aimed at improving general health. To our knowledge, only two studies have estimated the association between self-esteem and self-rated health, and none among college students.14 These studies have reported a significant relationship supporting the hypothesis that high self-esteem is associated with better self-rated health. In addition, a number of studies have evidenced associations between self-esteem and several important health-related outcomes: academic success, well-being and internalised/externalised mental health problems.15 16

Second, the population of college students has received little attention in this specific domain. Yet this period corresponding to the transition between adolescence and adulthood is crucial for the development of individuals, as well as for constructing and reinforcing self-esteem. Although the student population is in relatively good health, it is noteworthy that mental health and substance use issues are prevalent during the college years.17–19 On the one hand, self-rated health can serve to evaluate a general health status predicting future health problems before they set in. On the other hand, college is a period of development in which interventions could modify the onset of determinants such as psychosocial resources.

A final limitation is the lack of studies that adjust comprehensively for various risk factors (ie, the six domains reported above). This implies possible confounding biases that need to be addressed.

The aim of the present study was to estimate the association between self-esteem and subsequent self-rated health during college years, taking into account a wide range of potential confounders in the i-Share cohort.

Methods

Study population

This study is based on the internet-based Students Health Research Enterprise (i-Share, www.i-share.fr) project, a prospective population-based cohort study of students in higher education institutions in France. The i-Share cohort is one of the largest epidemiological studies conducted on European students and constitutes an opportunity to investigate this research question, thanks to its longitudinal collection of multidimensional data on childhood and family history, lifestyle, health information, living conditions and mental and psychosocial examinations.20 21 The objectives of the i-Share cohort are to evaluate important health aspects among university students over the course of 10 years. The eligibility criteria are to be officially enrolled at a university or higher education institution; to be at least 18 years of age; to be able to read and understand French; and to provide informed consent for participation. Recruitment started in February 2013 and is still ongoing. Students are informed about the objectives of the study through promotion campaigns. In particular, a group of trained students inform their peers about the study and initiate the online recruitment process. The baseline inquiry collected information on students’ health, personal and family medical histories, sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle habits. Afterwards, students receive an e-mail invitation to complete follow-up questionnaires annually (on each anniversary of the date of the baseline questionnaire) for 10 years and for substudy data collection. As of 6 February 2016, 14 795 participants were included in the cohort, with the average age being 21 years and 74% were female. The response rate for 1 year follow-up was 18% (n=2607). Since December 2015, an optional mental health survey has been conducted to provide data on several dimensions of mental and psychological health. For this specific study, we used the data available as of 29 April 2016. We used a longitudinal design to compare self-esteem data collected during the mental health substudy (time 2) with the next planned assessment of self-rated health (ie, during the first follow-up of the cohort, time 3). We used baseline characteristics collected at cohort inclusion for adjustment (time 1). Online supplementary figure S1 in the supplementary material describes the study timeline. Only college students aged between 18 and 30 years old and participating in the mental health substudy before their first follow-up were included. The i-Share project on which this study was based was approved by the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (DR-2013–019).

bmjopen-2018-024500supp001.pdf (109.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No participants were involved in setting the research questions or measurements or in developing plans for the design of the study. No participants were asked to advise on the interpretation or writing up of results. However, there are plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants via the i-Share website and social media and by means of a quarterly newsletter sent to participants via email. A group of trained students also participated during the recruitment process (ie, informed their peers about the study and initiated the online recruitment process). These students were also involved in the communication campaign, advising the study team about priority messages and communication tools.

Measures and scales

Outcome: self-rated health

Students gauged their current general self-rated health by the question: ‘Do you consider your current health?’ with a five-point response scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=‘Very poor’/2=”Poor’/3=‘Average’/4=”Good’/5=‘Very good’). The variable was dichotomised as follows: ‘Very good/Good’ versus ‘Average/Poor/ Very poor’. Psychometric performance of this assessment has been reported in two papers.7 8 Self-rated health was measured at inclusion of the participant and in follow-up questionnaires. The first follow-up self-rated health measure corresponded to the primary outcome of this study (time 3).

Main variable of interest: self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using the Self-Esteem Scale,22 a 10-item self-report measure of global self-esteem. Each item is answered on a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from 1=‘Strongly disagree’ to 4=‘Strongly agree’. The score can range from 10 (low level of self-esteem) to 40 (high level of self-esteem). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is the most widely used instrument for the measurement of global self-esteem.23 It was translated into French, and its high reliability and validity were confirmed with a French sample.24 Self-esteem measurement was part of the optional mental health survey (time 2). We used a continuous score for the primary analysis.

Covariates

All the covariates were collected through the self-administered online questionnaire at cohort enrolment (time 1), except for the psychosocial covariates that were part of the mental health substudy (ie, at the same time as self-esteem measurement, time 2). They all preceded the outcome to keep the longitudinal sequence between predictors and outcome. The covariates included in this study covered the six domains of potential determinants of self-rated health described in the literature:11

Demographic covariates

We built the following demographic variables: sex (male/female) and age (in years when the outcome was measured, time 3).

Academic covariates

Education level of student was collected at cohort inclusion and categorised into: freshman, sophomore, junior and senior. For parental education level, we used the education level of the parents declared by the students (at least one of their parents had a higher education level than baccalaureate vs not).

Financial covariates

Self-rated economic situation during childhood (‘Very difficult’/‘Difficult’/‘Correct’ vs ‘Comfortable’/‘Very comfortable’) and self-rated satisfaction about financial resources during college (‘Very satisfied’/‘Rather satisfied’ vs ‘Satisfied’/‘Rather dissatisfied’/‘Totally unsatisfied’).

Social covariates

Students’ living conditions (cohabitation with parents, flatsharing/couple or alone) and self-rated familial support during childhood (weak: ‘None at all’/‘A little’/‘Moderate’ vs high: ‘A lot’/‘Enormous’).

Geographical covariates

Students included in this study were spread over the French territory. To take disparities across college campuses into account we selected the four most constitutive cities of the registration university in the sample (Bordeaux/Versailles/Nice/Paris/other).

Behavioural covariates

Tobacco consumption (none, ≤10 cigarettes/day and >10 cigarettes/day). Binge drinking frequency was defined as drinking at least six drinks on the same occasion (evening) (never, rarely if ‘Once a year’, occasionally if ‘several times a year’/‘once a month’, frequently if ‘once a week or less’/‘2 to 3 times a week’/‘4 to 6 times a week’). Then students declared whether they consumed psychoactive substances at least once in their life, from cannabis, ecstasy, amphetamines, nitrous oxide, inhalation products and cocaine. To determine physical activity frequency, we combined walking times and sports by summing the count number of duration in minutes per day (<25, between 25 and 35 and >35). Body mass index (BMI) (<25 vs ≥25 kg/m²). Finally, good nutritional habits was based on adherence to The French National Nutrition and Health Program.25 Each of the seven nutrition recommendations was coded 0 if not followed and 1 if followed. The sum (seven representing the highest adherence to recommendations and 0 the lowest) was computed.

Psychosocial covariates

Coping was measured by the Student Coping Scale.26 Three subscores were computed representing social support coping, emotional coping and festive coping (a higher score represented higher coping resources). Aggressiveness was measured by an adaptation of the Brown-Goodwin assessment for Life History of Aggression, translated into French by Bellivier.27 Higher scores represented higher aggressiveness. Impulsivity was measured by an Adolescent Version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 translated into French by Coudrey F and Michel G.28 Higher scores represented higher impulsivity. Personality traits were measured by the Temperament and Character Inventory translated into French by Pélissolo F.29 30 Six subscores were computed: novelty seeking, persistence, harm avoidance, determination, reward dependence and cooperativeness. Higher scores represented greater adherence to the type of personality.

Objective health indicator

Participants with at least one medical diagnosis for mental or physical diseases or disability at cohort inclusion.

Study size

We performed a sample size calculation for logistic regression between self-esteem and self-rated health, alpha 0.05 and power 0.90. Based on two French studies among college students, we assumed that the distribution of self-esteem was normal (mean=28.9, SD=5.7).31 32 The proportion of participants declaring having good or very good health has been estimated in two studies in Sweden and Italy among college students to be 13% and 23%, respectively.33 34 We assumed the OR to be 1.1 based on the only two studies reported among high school students in South Korea and adults in Canada.14 The minimum required sample size was between 232 and 344 based on self-rated health proportions (SAS software PROC POWER).

Statistical analysis

First, we described the study sample. Then, in order to estimate the association between self-esteem and self-rated health, we computed a logistic regression model. We modelled the probability of declaring good or very good self-rated health during the first follow-up. The primary explanatory variable was self-esteem. To allow relevant interpretation, we estimated associations for the increase of one SD (ie, 5.696). All the potential confounders described above were entered in the model as covariates. In the modelling process, we first estimated univariate models. Log-linearity of the effect of self-esteem (continuous variable) was checked. We tested interactions for gender, age and cities among self-rated health and self-esteem links by univariate models and performed stratified analysis if the interaction was significant (p<0.05). Then we selected variables if p value <0.25 to compute multivariate models. Finally, we performed a stepwise backward selection for a final multivariate model with a threshold of p value=0.05. At every step, we checked the confusion effect and computed the OR, 95% CI and p value (p) of the corresponding Wald test.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the findings: (1) modelling self-rated health: (A) in continuous variable (ranging from 1 to 5) and (B) in three categories (with an ‘average’ modality); (2) estimating the self-esteem effect through a categorised variable (corresponding to quartiles: ≤25, ]25–28], ]28–33] and >33) to bring to light a potential dose–response effect; (3) completing the adjustment: (A) with baseline self-rated health; (B) forcing the adjustment with delays between the three measurement periods; and (C) with objective health indicators; and (4) performing primary modelling among the complete case population.

Our missing data analysis procedures used missing at random assumptions. We used the multivariate imputation by chained equations method of multiple multivariate imputation in SAS software (PROC MI and MIANALYZE).35 36 We independently analysed 10 copies of the data, each with suitably imputed missing values, in the multivariate logistic regression analyses. We averaged estimates of the variables to give a single mean estimate and adjusted standard errors according to Rubin’s rules. We imputed only data from covariates using self-esteem, self-rated health, covariate data and completed the imputation process with other data collected in the i-Share cohort (alcohol consumption, walking time per day, sport practice time, stress score, anxiety score, depression score and self-rated quality of sleep).

We performed all analyses using the SAS statistical software (SAS V.9.3).

Results

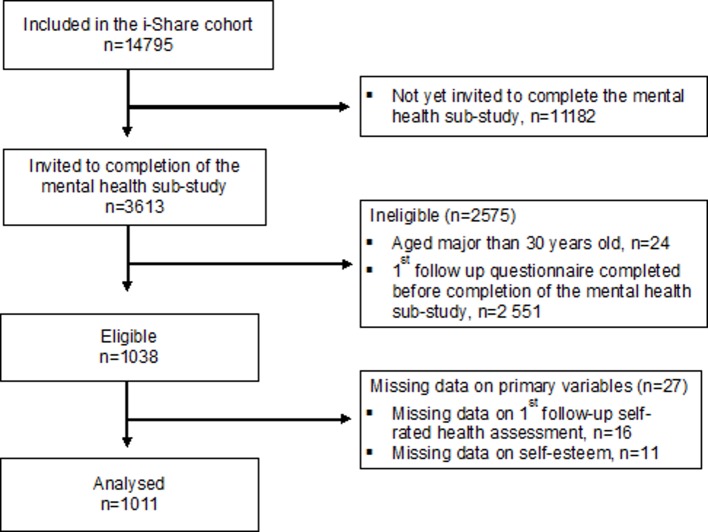

The total sample comprised 1011 participants. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study population. Of the 14 795 college students enrolled in the i-Share cohort, 3613 completed the mental health substudy, 1038 were eligible for this study and 1011 were ultimately analysed. Prospective self-rated health assessment (ie, during the first follow-up, time 3) was a median of 13.2 months after enrolment in the cohort and a median of 8.4 months after completion of the mental health substudy (ie, self-esteem measure, time 2). The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in table 1. The mean age of participants was 20.8 (SD=2.3) years, 795/1011 (79%) were female, 367/1011 (37%) were freshmen and most students were in Bordeaux (686/1011, 68%). 346/1011 (34%) participants had at least one missing data item among covariates. BMI and living situation were the most frequently missing variables (15% and 12%, respectively) and other missing variables accounted for less than 5% of missing data. At inclusion, 18% of the students declared average or poor health (183/1011). At first follow-up, 20% of the students declared average or poor health (203/1011). Online supplementary table S1 in the supplementary material compares participants in the i-Share cohort versus the study sample.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing participant flow through the study based on the i-Share cohort, France, 2013–2016.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population concerning self-rated health, self-esteem, demographic, educational, financial, social, geographical, follow-up, behavioural and psychological data at time 1: cohort enrolment; time 2: optional mental health survey; time 3: cohort follow-up in the i-Share cohort, France, 2013–2016

| Characteristics | Participants n=1011 |

| Outcome at time 3 | |

| SRH five items, n (%) | |

| Very good | 225 (22.3) |

| Good | 583 (57.7) |

| Average | 177 (17.5) |

| Poor | 26 (2.6) |

| Very poor | 0 (–) |

| SRH dichotomised, n (%) | |

| Very good to good | 808 (79.9) |

| Average to very poor | 203 (20.1) |

| SRH in continuous*, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) |

| Main exposure at time 2 | |

| Self-esteem in continuous variable, median (IQR) | 28 (25–33) |

| Self-esteem in categorical variable, n (%) | |

| ≤25 | 287 (28.4) |

| ]25–28] | 219 (21.7) |

| ]28–33] | 277 (27.4) |

| ≥33 | 228 (22.6) |

| Demographic data | |

| Age at time 3, mean (STD) | 20.8 (2.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 795 (78.6) |

| Educational data at time 1 | |

| University year, n (%) | |

| Freshman | 367 (36.5) |

| Sophomore | 218 (21.7) |

| Junior | 154 (15.3) |

| Senior | 267 (26.5) |

| At least one parent with high education level, n (%) | 274 (28.5) |

| Financial data at time 1 | |

| Comfortable to very comfortable financial situation during childhood, n (%) | 573 (56.7) |

| Rather satisfied to very satisfied with financial resources, n (%) | 504 (49.8) |

| Social data at time 1 | |

| Cohabitation, n (%) | |

| With parents | 278 (31.3) |

| Flatsharing or couple | 287 (32.4) |

| No cohabitation/alone | 322 (36.3) |

| Strong familial support during childhood, n (%) | 730 (72.9) |

| Geographical and follow-up data | |

| City of the registration university at time 1, n (%) | |

| Bordeaux | 686 (67.9) |

| Versailles | 77 (7.6) |

| Nice | 22 (2.2) |

| Paris | 45 (4.5) |

| Other | 181 (17.9) |

| Delay in months between inclusion and SRH assessment (follow-up), median (IQR) | 13.2 (12.3–23.4) |

| Delay in months between mental health assessment and SRH assessment (follow-up), median (IQR) | 8.4 (3.2-12.0) |

| Behavioural data at time 1 | |

| Tobacco consumption, n (%) | |

| None | 761 (75.3) |

| ≤10 cigarettes | 213 (21.1) |

| >10 cigarettes | 37 (3.6) |

| Alcohol consumption frequency during evening, n (%) | |

| Never | 22 (2.3) |

| Rarely | 225 (23.2) |

| Occasionally | 393 (40.5) |

| Frequently | 330 (34.0) |

| Psychoactive substance consumption at least once in life, n (%) | 603 (59.6) |

| BMI <25 kg/m² at time 1, n (%) | 909 (89.9) |

| Compliance with French nutritional recommendations, median (IQR) | 3 (3.4) |

| Physical activity, n (%) | |

| Less than 25 min/day | 109 (10.9) |

| Between 25 and 35 min/day | 183 (18.3) |

| More than 35 min/day | 706 (70.7) |

| Psychological data at time 2, median (IQR) | |

| Coping – social support | 11 (8–14) |

| Coping – emotional | 20 (17–22) |

| Coping – festive-addictive | 11 (9–14) |

| Impulsivity | 61 (56–67) |

| Aggressiveness | 1 (0–3) |

| Personality – novelty seeking | 21 (18–23) |

| Personality – persistence | 28 (24–31) |

| Personality – harm avoidance | 27 (22–31) |

| Personality – determination | 27 (23–31) |

| Personality – reward dependence | 28 (23–32) |

| Personality – cooperativeness | 32 (29–35) |

n=1011.

*1=very good, 2=good, 3=average, 4=poor and 5=very poor.

BMI, body mass index; SRH, self-rated health.

Table 2 presents the whole modelling process after imputation of missing data and table 3 presents the final model with crude and adjusted ORs. The unadjusted self-esteem effect (for the increase of one SD) on self-rated health was statistically significant (OR=1.70, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.99, p<0.0001). Log-linearity of the self-esteem effect was confirmed, allowing a valid estimation. None of the predefined interactions (gender, cities and age) were statistically significant (all p values >0.10). The final multivariate model was adjusted for BMI, financial situation during childhood and three personality traits (persistence, harm avoidance and cooperativeness). With this final model, the increase of one SD in self-esteem was associated with a 40% increase in the probability of declaring good or very good health versus average to very poor health (adjusted OR=1.40, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.72, p=0.001).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic model of probability to declare good or very good compared with very poor, poor or average self-rated health after imputation of missing data on covariates

| Univariate model | Multivariate model | |||

| OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Main exposure | ||||

| Self-esteem (for an increase of one SD†) | 1.70 | 1.44 to 1.99*** | 1.40 | 1.15 to 1.72*** |

| Covariates | ||||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | – | ||

| Female | 0.48 | 0.31 to 0.74*** | ||

| Age at self-rated health assessment (follow-up) | 0.98 | 0.92 to 1.04 | ||

| Educational data | ||||

| University year at inclusion | * | |||

| 1st year/freshman | 1 | – | ||

| 2nd year/sophomore | 1.54 | 1.00 to 2.37 | ||

| 3rd year/junior | 1.60 | 0.98 to 2.62 | ||

| 4th year or more/senior | 1.22 | 0.83 to 1.80 | ||

| Parents’ education level | ||||

| At least one with high level | 1 | – | ||

| Both with low level or only one given with low level | 0.86 | 0.60 to 1.22 | ||

| Financial data | ||||

| Financial situation during childhood | ||||

| Comfortable to very comfortable | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Correct to very difficult | 0.48 | 0.36 to 0.66*** | 0.54 | 0.39 to 0.74*** |

| Satisfaction with financial resources at inclusion | ||||

| Rather satisfied to very satisfied | 1 | – | ||

| Completely dissatisfied to satisfied | 0.55 | 0.40 to 0.75*** | ||

| Social data | ||||

| Cohabitation at inclusion | ||||

| No cohabitation | 1 | – | ||

| With parents | 1.03 | 0.70 to 1.51 | ||

| Flat sharing or couple | 1.12 | 0.76 to 1.64 | ||

| Familial support during childhood | ||||

| Strong | 1 | – | ||

| Weak | 0.56 | 0.40 to 0.78*** | ||

| Geographical and follow-up data | ||||

| City of the registration university | ||||

| Bordeaux | 1 | – | ||

| Versailles | 1.16 | 0.63 to 2.14 | ||

| Nice | 1.16 | 0.39 to 3.49 | ||

| Paris | 1.04 | 0.49 to 2.20 | ||

| Other | 1.08 | 0.71 to 1.63 | ||

| Delay in months between inclusion and self-rated health assessment (follow-up) | 1.00 | 0.97 to 1.03 | ||

| Delay in months between mental health assessment and self-rated health assessment (follow-up) | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.02 | ||

| Behavioural data | ||||

| Tobacco consumption at inclusion | ||||

| None | 1 | – | ||

| ≤10 cigarettes | 0.97 | 0.66 to 1.42 | ||

| >10 cigarettes | 0.66 | 0.31 to 1.40 | ||

| Alcohol consumption frequency during evening at inclusion | ** | |||

| Never drink | 1 | – | ||

| Never binge | 1.09 | 0.41 to 2.91 | ||

| Occasionally binge | 1.53 | 0.58 to 4.05 | ||

| Frequently binge | 1.99 | 0.75 to 5.33 | ||

| Psychoactive substance consumption | ||||

| Never | 1 | – | ||

| Once in life | 1.26 | 0.92 to 1.72* | ||

| BMI at inclusion | ||||

| <25 kg/m² | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| ≥25 | 0.52 | 0.33 to 0.81*** | 0.50 | 0.31 to 0.80*** |

| Compliance with French nutritional recommendations | 0.97 | 0.85 to 1.10 | ||

| Physical activity | ||||

| More than 35 min/day | 1 | – | ||

| Less than 25 min/day | 0.89 | 0.54 to 1.44 | ||

| Between 25 and 35 min/day | 1.01 | 0.67 to 1.52 | ||

| Psychological data | ||||

| Coping | ||||

| Social support | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.08* | ||

| Emotional | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.97*** | ||

| Festive-addictive | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.09* | ||

| Impulsivity | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.01* | ||

| Aggressiveness | 0.95 | 0.90 to 1.00** | ||

| Personality | ||||

| Novelty seeking | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.06* | ||

| Persistence | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.97*** | 0.94 | 0.91 to 0.97*** |

| Harm avoidance | 0.91 | 0.89 to 0.94*** | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98*** |

| Determination | 1.07 | 1.04 to 1.10*** | ||

| Reward dependence | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.06** | ||

| Cooperativeness | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.08*** | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.08** |

The i-Share cohort, France, 2013–2016. n=1011.

*P value <0.25; **p value <0.05; ***p value <0.01.

†Self-esteem SD: 5.696.

‡Self-rated health description provided before data imputation.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 3.

Final logistic model of probability to declare good or very good compared with very poor, poor or average self-rated health after imputation of missing data on covariates

| Self-rated health* | Multivariate model | |||

| Good/very good, n=808 | Average/poor, n=203 | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Self-esteem (for the increase of one SD†), median (IQR) | 29 (26–33) | 26 (22–30) | 1.40 | 1.15 to 1.72*** |

| BMI at inclusion, n(%) | ||||

| <25 kg/m² | 623 (89.6) | 130 (81.3) | 2.11 | 1.26 to 3.53*** |

| ≥25 | 72 (10.4) | 30 (18.8) | 1 | – |

| Financial situation during childhood, n(%) | ||||

| Comfortable to very comfortable | 487 (60.3) | 86 (42.4) | 1.87 | 1.35 to 2.59*** |

| Correct to very difficult | 321 (39.7) | 117 (57.6) | 1 | – |

| Personality, median (IQR) | ||||

| Persistence | 29 (24–31) | 29 (25–33) | 0.94 | 0.91 to 0.97*** |

| Harm avoidance | 26 (22–30) | 29 (25–33) | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98*** |

| Cooperativeness | 32 (29–35) | 32 (28–35) | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.08** |

The i-Share Cohort, France, 2013–2016. n=1011.

*P value <0.25; **p value <0.05; ***p value <0.01.

*Self-rated health description provided before data-imputation.

†Self-esteem SD: 5.696.

aOR, adjusted OR; BMI, body mass index.

BMI >25 kg/m² and difficult financial situation during childhood decreased the probability of declaring good to very good health by 2. Three personality traits were associated with self-rated health: low persistence and harm avoidance and high cooperativeness were associated with declaring good to very good health. The restraint model showed acceptable discrimination power (area under curve=0.7205), and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test proved model suitability to data (p value=0.8614).

Table 4 presents sensitivity analysis results showing the robustness of findings. Whatever the modelling choices for self-rated health and self-esteem or adjusting strategies, higher self-esteem was persistently associated with better self-rated health. Furthermore, the model with self-esteem in four categories showed a dose–response effect with graduate adjusted OR and a significant global test (p<0.04).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of self-esteem on self-rated health

| Estimation* of increase of one SD† for (1) (3) and (4) natural scale for (2) of self-esteem effect on self-rated health | |

| (1) Modelling self-rated health | |

| (A) in continuous variable (ranging from 1 to 5)‡ | β=−0.05, p=0.0005 |

| (B) in three categories (with a ‘average’ modality) | |

| Average versus poor/very poor | OR=1.69, p=0.0429 |

| Good/very good versus poor/very poor | OR=2.23, p=0.0015 |

| (2) Estimating self-esteem effect throughout a categorised variable | |

| ]25–28) versus ≤25 | OR=1.25, p=0.3032 |

| ]28–33) versus ≤25 | OR=2.28, p=0.0009 |

| >33 vs≤25 | OR=1.85, p=0.0301 |

| (3) Completing adjustment | |

| (A) With baseline self-rated health | OR=1.29, p=0.0160 |

| (B) Forcing the adjustment with delays between the three measurement periods | OR=1.40, p=0.0009 |

| (C) With objective health indicator | OR=1.40, p=0.0011 |

| (4) Performing primary modelling among complete case population (n=665) | OR=1.55, p=0.0009 |

The i-Share Cohort, France, 2013–2016. n=1011.

*Models adjusted for body mass index, financial situation during childhood and personality scores (persistence, harm avoidance and cooperativeness).

†Self-esteem SD: 5.696.

‡High score represent better self-rated health.

Discussion

Findings of the study

In this large longitudinal study among college students, higher self-esteem levels were independently associated with better self-rated health, even after complete adjustment for known confounders. This association was not modified by gender or age. Additional risk factors such as BMI, financial situation during childhood and personality traits (persistence, harm avoidance and cooperativeness) were associated with self-rated health. This original finding opens up an opportunity for interventional research targeting psychosocial resources, especially self-esteem, in the university setting.

Interpretation

The association between higher levels of self-esteem and better self-rated health found in the current study corroborates previous research. This finding based on a sample of college students supports and extends previous studies on other population samples by showing the same pattern of association between self-esteem and self-rated health.14 Several research works and literature reviews formulate hypotheses on the potential underlying mechanisms that may explain the relationship between self-esteem and health. Good self-esteem may enable individuals to make better choices, including adopting healthy behaviours.16 High self-esteem may increase the ability to put in place appropriate strategies to cope with everyday situations, which in turn increases the capacity to feel well and more generally the capacity of resilience.37 An alternative hypothesis is based on bodily sensations (ie, information that conveys messages from the organism to the brain). This information is available to the individual consciousness, is included in self-rating of health and may reflect important physiological dysregulation, such as inflammatory processes.38 In this hypothesis, self-esteem appears to be a psychosocial ability that allows individuals to cope better with stress and prevents or diminishes these deleterious inflammatory processes. Throughout the literature, several determinants of self-rated health have been found.11 Our study was consistent with this in finding that a low BMI, a comfortable financial situation during childhood and three personality traits were associated with good self-rated health. In contrast to the literature, we did not find gender differences for self-rated health after complete adjustment.39–41 This discordant result could be due to differences in sampling and adjustment strategies. In particular, fewer males than women participated in the i-Share cohort. Moreover, we found that self-rated health was influenced more by the family’s financial difficulties during childhood than during college years.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the longitudinal design, standardised assessment tools and broad adjustment for confounders. In addition, this study investigates self-rated health among college students, a population that has received less attention in the literature. Although the study sample included only a fraction of the original i-Share cohort, the number of participants was still relatively high compared with the available studies in the area. A set of limitations should be taken into consideration, however, to interpret the findings properly. First, a sampling bias could have arisen since participants were mainly healthy female students. Since young females usually have lower self-reported health than males, caution should be taken regarding extrapolation of the results to males.42 Further research is needed with a larger and more varied sample. Second, we used a longitudinal design with a median follow-up period of 8 months, which is relevant to assess impact on self-rated health in young adults. We do not have any information on the persistency of the self-esteem/self-rated health relationship in the longer term, however, especially after the academic years. Moreover, reverse causation between self-esteem and self-rated health may exist and could not be investigated with our design. However, in sensitivity analyses, when self-rated health measurement prior to self-esteem was entered in the model as a covariate, the result remained similar. Further research should use repeated self-esteem and self-rated health measurements to better explore the bidirectionality assumption.

Implications

From a public health perspective, this study provides a contributive insight for interventional research. It suggests that interventions targeting self-esteem during college years should be experimented. Yet the type of intervention is still to be determined, since most of the previous interventional research on self-esteem has concerned children.43 44 Consequently, further studies are needed to investigate whether these interventions could be extended or transferred to college students. Self-esteem improvement interventions could focus either on (1) global self-esteem by increasing self-knowledge and resilience through an individual intervention, web-based for instance, or (2) a specific dimension such as social self-esteem by using exercise or mentoring programme.43 44 Furthermore, the university years represent a relevant period for implementing early interventions, before health behaviours and mental health problems set in.

From a research perspective, we have identified two priority areas. First, it appears necessary to better understand the pathways between self-esteem and self-rated health by conducting mediational analyses. Second, the self-reported nature of the two measurements (ie, self-esteem and self-rated health) might explain why they are linked.38 Considering that self-esteem has been reported to be linked with health outcomes other than self-rated health, we believe that there are coexisting associations with both the evaluation framework and health.

bmjopen-2018-024500supp002.pdf (17.4KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the participants of the i-Share project for their commitment and cooperation and to the entire i-Share staff for their expert contribution and assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: JA and CG developed the study concept and study design. CT is the principal investigator of the i-Share Cohort. MT and GM participated actively in the creation of the mental health questionnaire and brought psychological and psychiatric expertise to the interpretation of the results. JA performed the data analysis and interpretation under the supervision of CG. JA drafted the manuscript and all the coauthors provided critical revisions. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding: The i-Share research project has received funding from the French National Research Agency (Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR)) via the ‘Investissements d’Avenir’ programme reference ANR-10- COHO-05. This study was further supported by a grant from the ‘Health Determinants in Societies’ HEADS Excellence Cluster of the University of Bordeaux, managed by the ANR, under the ‘Future Investments’ programme in the framework of the Bordeaux ‘Initiatives d’Excellence’ (IdEx) programme, grant number (ANR-10-IDEX-03-02).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the study are not available because they are still under analysis for other research questions.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Nielsen TH. The relationship between self-rated health and hospital records. Health Econ 2016;25:497–512. 10.1002/hec.3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sajjad A, Freak-Poli RL, Hofman A, et al. Subjective measures of health and all-cause mortality - the Rotterdam Study. Psychol Med 2017;47:1971–80. 10.1017/S0033291717000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breidablik HJ, Meland E, Lydersen S. Self-rated health in adolescence: a multifactorial composite. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:12–20. 10.1177/1403494807085306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Breidablik H-J, Meland E, Lydersen S. Self-rated health during adolescence: stability and predictors of change (Young-HUNT study, Norway). Eur J Public Health 2009;19:73–8. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ware J. The assessment of health status : Applications of social science to clinical medicine and health policy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press:204–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Bruin A. Health Interview Surveys: Towards International Harmonization of Methods and Instruments. WHO Regional Publications, European Series, No. 58 [Internet: Office of Publications, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen 0, Denmark (39 Swiss francs), 1996. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED3949619.R. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robine JM, Jagger C. Euro-REVES Group. Creating a coherent set of indicators to monitor health across Europe: the Euro-REVES 2 project. Eur J Public Health 2003;13(3 Suppl):6–14. 10.1093/eurpub/13.suppl_1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1982;72:800–8. 10.2105/AJPH.72.8.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mantzavinis GD, Pappas N, Dimoliatis IDK, et al. Multivariate models of self-reported health often neglected essential candidate determinants and methodological issues. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:436–43. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bobak M, Pikhart H, Rose R, et al. Socioeconomic factors, material inequalities, and perceived control in self-rated health: cross-sectional data from seven post-communist countries. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1343–50. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00096-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mackenbach JP, Simon JG, Looman CWN, et al. Self-assessed health and mortality: could psychosocial factors explain the association? Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1162–8. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shields M, Shooshtari S. Determinants of self-perceived health. Health Rep. déc 2001;13:35–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, et al. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest 2003;4:1–44. 10.1111/1529-1006.01431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mann M, Hosman CMH, Schaalma HP, de Vries NK. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ Res 2004;19:357–72. 10.1093/her/cyg041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Carlin JB, et al. Outcomes of occasional cannabis use in adolescence: 10-year follow-up study in Victoria, Australia. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:290–5. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mota N, Álvarez-Gil R, Corral M, et al. Risky alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking among Spanish University students: a two-year follow-up. Gac Sanit 2010;24:372–7. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van De Ven MOM, Greenwood PA, Engels RCME, et al. Patterns of adolescent smoking and later nicotine dependence in young adults: A 10-year prospective study. Public Health 2010;124:65–70. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Montagni I, Guichard E, Kurth T. Association of screen time with self-perceived attention problems and hyperactivity levels in French students: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009089 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galéra C, Salla J, Montagni I, et al. Stress, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and tobacco smoking: The i-Share study. Eur Psychiatry 2017;45:221–6. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, NJ: Princeton University Press [Internet]. 1965 [cité 29 avr 2019]. Disponible sur. https://www.docdroid.net/Vt9xpBg/society-and-the-adolescent-self-image-morris-rosenberg-1965.pdf.

- 23. Blascovich J, Tomaka J. Measures of self-esteem : Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes: measures of social psychological attitudes: Academic Press, 2013:115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chambon O, Cornillon-Jacoudon D, Germain M, et al. Bien-être subjectif et qualité de vie. Définitions, mesures et facteurs déterminants. Implications thérapeutiques. Inf Psychiatr 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hercberg S, Chat-Yung S, Chaulia M. The French National Nutrition and Health Program: 2001-2006-2010. Int J Public Health 2008;53:68–77. 10.1007/s00038-008-7016-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boujut E, Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Dombrowski S. Coping among Students: Development and Validation of an Exploratory Measure. Psychology 2012;03:562–8. 10.4236/psych.2012.38084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, et al. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979;1:131–9. 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90053-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fossati A, Barratt ES, Acquarini E, et al. Psychometric properties of an adolescent version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 for a sample of Italian high school students. Percept Mot Skills 2002;95:621–35. 10.2466/PMS.95.6.621-635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cloninger CR, Bayon C, Svrakic DM. Measurement of temperament and character in mood disorders: a model of fundamental states as personality types. J Affect Disord 1998;51:21–32. 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pelissolo A, Mallet L, Baleyte JM, et al. The Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R): psychometric characteristics of the French version. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:126–33. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00551.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Estingoy P, Fort E, Normand J-C, et al. Vulnérabilités psychiques chez les étudiants : à propos de deux enquêtes en santé mentale à l’université Lyon 1. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique 2013;171:392–8. 10.1016/j.amp.2013.04.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saleh D, Camart N, Romo L. Predictors of Stress in College Students. Front Psychol 2017;8 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. von Bothmer MIK, Fridlund B. Self-rated health among university students in relation to sense of coherence and other personality traits. Scand J Caring Sci 2003;17:347–57. 10.1046/j.0283-9318.2003.00234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de WC, Soffiani V, Virdis A, et al. Italian university students’ self-perceived health and satisfaction of life. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità. juin 2015;51:121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-are databases: An overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991;10:585–98. 10.1002/sim.4780100410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data: CRC Press, 1997:448. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harter S. The construction of the self: a developmental perspective. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:307–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmidt M. Predictors of self-rated health and lifestyle behaviours in Swedish university students. Glob J Health Sci 2012;4:1–14. 10.5539/gjhs.v4n4p1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cullati S, Rousseaux E, Gabadinho A, et al. Factors of change and cumulative factors in self-rated health trajectories: A systematic review. Adv Life Course Res 2014;19:14–27. 10.1016/j.alcr.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. El Ansari W, Stock C. Explaining the gender difference in self-rated health among university students in Egypt. Women Health 2016;56:731–44. 10.1080/03630242.2015.1118733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kling KC, Hyde JS, Showers CJ, et al. Gender differences in self-esteem: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 1999;125:470–500. 10.1037/0033-2909.125.4.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. King KA, Vidourek RA, Davis B, et al. Increasing self-esteem and school connectedness through a multidimensional mentoring program. J Sch Health 2002;72:294–9. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb01336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ekeland E, Heian F, Hagen KB, et al. Exercise to improve self-esteem in children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;1:CD003683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024500supp001.pdf (109.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024500supp002.pdf (17.4KB, pdf)