Abstract

Purpose

To establish a cohort that enables identification of genomic factors that influence human health and empower increased blood donor health and safe blood transfusions. Human health is complex and involves several factors, a major one being the genomic aspect. The genomic era has resulted in many consortia encompassing large samples sizes, which has proven successful for identifying genetic factors associated with specific traits. However, it remains a big challenge to establish large cohorts that facilitate studies of the interaction between genetic factors, environmental and life-style factors as these change over the course of life. A major obstacle to such endeavours is that it is difficult to revisit participants to retrieve additional information and obtain longitudinal, consecutive measurements.

Participants

Blood donors (n=110 000) have given consent to participate in the Danish Blood Donor Study. The study uses the infrastructure of the Danish blood banks.

Findings to date

The cohort comprises extensive phenotype data and whole genome genotyping data. Further, it is possible to retrieve additional phenotype data from national registries as well as from the donors at future visits, including consecutive measurements.

Future plans

To provide new knowledge on factors influencing our health and thus provide a platform for studying the influence of genomic factors on human health, in particular the interaction between environmental and genetic factors.

Keywords: genetics, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cohort design allows for consequative meassurements.

Diesase status is continuously reassesset.

The cohort consist of select population of blood donors.

Introduction

A person’s health is determined by complex interactions between genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors. Analysing these factors collectively and prospectively is preferable. However, this is usually only possible using birth-cohorts and large population-based cohorts, and due to the extensive effort involved in establishing such cohorts, they are rare. The Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS; dbds.dk) is a large prospective cohort of blood donors aiming at identifying predictors of healthy donors. As part of this cohort, we have now established DBDS Genomic Cohort assessing common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 110 000 donors. Thus, the DBDS Genomic Cohort provides a comprehensive catalogue for large-scale genetic analyses in relation to numerous environmental and lifestyle factors affecting donor’s health. A description of summary statistics on phenotypes and data coverage is provided in table 1. A detailed sociodemographic description of Danish blood donors, including sex and age distribution, ethnicity, education, employment and level of urbanisation is found in Burgdorf et al (2017).1

Table 1.

Prevalence and missingness of environmental variables

| Participants | Missingness (%) | |

| Men | 48.8% | 0 |

| Women | 51.2% | 0 |

| Age* | 41 (29–50)* | 0 |

| Height (cm)* | 175.6 (169–182) | 0.53 |

| Weight (kg)* | 78.1 (67–87) | 0.82 |

| BMI | 25.3 (22–27) | 1.2 |

| Smoking | 11.9% | 1.3 |

| Alcohol consumption (daily) | 3.0% | 4.7 |

| Questionnaire 1 | 87 000 | |

| Questionnaire 2 | 50 000 |

*Mean (Quartiles).

BMI, body mass index.

The evaluation of blood donor’s health is important for several reasons. It is crucial for both the donor and the blood recipient that a healthy donor population is maintained with a high donation rate and a low dropout rate, thereby ensuring a steady blood supply. Evidence-based guidelines for donor recruitment, care and retention are needed to ensure that donor recruitment can focus on individuals who are likely to remain healthy and donate frequently in the long term. One obvious relevant influential parameter relates to iron metabolism: we know that hundreds of genes impact the generation and regulation of blood cells2 and also influence phenotype variations of iron absorption and metabolism.3–5 Genome-wide SNP information is expected to provide knowledge enabling us to evaluate to whom donating blood will be unproblematic, thus facilitating retention of a stable blood donor population. Another parameter is altruism. Altruism as part of a prosocial behaviour, the selfless concern for the welfare of others,6 is generally considered a typical blood donor characteristic.7 However, altruism in the context of voluntary blood donation has also been shown to be a very complex phenotype.7 In a previous study, we found a substantially larger genetic influence on blood donor behaviour compared with most previous twin studies on altruism, which further highlights the heterogeneity of the blood donor personality.8 The considerable amount of kinship (twins and siblings) in the cohort in combination with socioeconomic variables from the Danish registries will enable us to further differentiate between genetic impact and social basis of altruism in blood donation. The genome-wide SNP information will provide knowledge that can aid in the identification of long-term and steady donors. Further, we will test for association between genotype SNP information and prodromal symptoms of somatic and psychiatric disease or illnesses.

The DBDS Genomic Cohort offers the possibility to assess the impact of heterogeneous exposures in a broad range of phenotypes, such as mental state, risk-taking behaviour and characterisation of blood components and immune defense. The setup of the study allows for researchers to assess the genetic association in (1) cross sectional studies to investigate, that is, the variation of phenotypic characteristic, clinical and biochemical measurements, (2) retrospective studies of, for example, rehabilitation capacity and (3) prospective studies, for example, analysing the variation of phenotypes and clinical measurements over time and even identify prodromal symptoms.

Cohort description

Population

The nation-wide blood donor population in Denmark consists of more than 230 000 donors giving more than 300 000 blood donations annually (http://www.bloddonor.dk). Blood donation in Denmark is voluntary and unpaid. This means that the donation is based on the desire to help others, who need it and not the desire of an economic benefit. Blood donors must be physically well, aged 17 and 67 years, and weigh more than 50 kilos. Individuals in chronic medical treatment or frequent travellers to countries with high prevalence of blood disease are not allowed to participate. The deferral rules can be seen at http://www.bloddonor.dk. Blood donors from foreign countries must have lived in Denmark for a minimum of 1 year, have a Danish social security number and have learnt the Danish language to prevent misunderstandings between the donor and the blood bank professionals.

The nationwide Danish blood bank is an integrated part of the Danish healthcare system financed by local and state taxes. The Danish healthcare system is administrated by democratically elected assemblies from national state institutions, regions and municipalities. The Danish blood banks are non-profit organisations owned and operated by each of the five regions in Denmark. The blood banks have a national board to structure collaboration across regions on recruiting donors, processing and distributing the blood for the Danish population. The DBDS is building on the structured Danish blood bank system in the regions responsible for administering donation sites at 27 hospitals in addition to five mobile donation units using 180 selected sites nationally (eg, large companies, sports centres and universities)

At the blood donation centres and attached laboratories, the entire necessary infrastructure needed for the collection of biological samples and structured data is in place. Both blood plasma and whole blood for DNA extraction are available from all donors. The blood bank infrastructure already has laboratory facilities with educated staff (nurses, technicians, IT specialists and physicians). In addition, the blood bank professionals facilitate the testing of the blood for a variety of biomarkers and holds expertise in large scale storage of biological material.

Contact to participants at the blood banks is fundamental to our study. Blood donors are asked to participate and sign an informed consent when they visit the blood bank to donate blood. This consent allows us to use the blood samples from their past and future donations to study the impact of genetic and immunological factors on current and future health and disease. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for blood donation and participation in DBDS are the same with 95% of the blood donors who are invited agrees to participate in DBDS.9

Questionnaires

From March 2010 until July 2015, all participating donors had to complete a four-page paper-based questionnaire with questions of self-experienced physical and mental health including the 12-item short form (SF-12) standardised health survey, smoking habits, alcohol intake, exercise, food intake, supplemental iron intake, height, weight and waist circumference. Total 85 000 individuals filled out the paper questionnaire. As a follow-up to the initial paper-based questionnaire, we have developed and implemented a digital and flexible tablet-based questionnaire platform, using the open source survey software tool LimeSurvey.10 This enables a rapid, easy and cost-effective procedure to collect self-reported data on health traits from the participating donors at the donor sites at multiple time-points. The first digital questionnaire was implemented and used from July 2015 until May 2018. The questionnaire focused on the following research questions: allergy, ADHD, migraine, hidradenitis, depression and Restless Legs Syndrome. It also contains questions from the paper-based questionnaire: SF-12, smoking habits, alcohol intake, height and weight. In total, 48 000 DBDS participants completed the first digital questionnaire. The second digital questionnaire started in June 2018. It includes questions on: sleep patterns, anxiety, migraine, stress, skin diseases, endometriosis, pain, learning difficulties, SF-12, smoking habits, alcohol intake, height and weight. Using the questionnaire data, several studies have already assessed the factors describing the general health of blood donors, for example, hidradentis,11 risk of infection,12 migraine, restless legs and depression.13 14 Also, by revisiting samples, it has been possible to assess whether infections correlates with obesity15 and how iron deficiency and haemoglobin levels affect donor health in general.16 17

Registry-based data

There is and has always been equal access to the healthcare system in Denmark; hence, the centralised national civil and health registries are unbiased and comprehensive resources of healthcare data. The registries include the National Patient Registry containing all hospital-registered diagnoses since 197518 as well as other specialised registries, for example, the Danish Medical Birth Register, the Danish Register of Causes of Death and Statistics Denmark monitoring, for example, socioeconomic data. We have already used the DBDS cohort in epidemiological studies assessing, for example, the mortality19 of donors and the effect of blood donation on offspring birth weight.20

DBDS organisation

The DBDS itself is described in detail by Pedersen et al.9 Briefly, DBDS is governed by a steering committee with a scientific advisory board. All projects are managed by the DBDS steering committee. Genetic projects involving genetic data in DBDS are run in collaboration between DBDS Genomic Consortium that consists of the DBDS steering committee, deCODE Genetics and scientific collaborators.

Genotyping: DNA is purified from whole blood and subsequent stored at −20°C. All samples are then genotyped in two batches at deCODE genetics using the Global Screening Array by Illumina (batch 1, n=85 000 and batch 2, n=25 000). The array has a very rich up-to-date content of >650 000 SNPs with custom chip content optimised for comparison with the Illumina Omni Express chip. All genotype data are processed simultaneously for genotype calling, quality control and imputation. Initially, individuals or SNPs with more than 10% missing data are excluded, as are individuals deviating more than three SD from the population heterozygosity (correcting for individuals carrying large copy number variations (CNVs) (>100 Kbp)).

Imputation

The genotyping data are imputed using a reference panel backbone consisting of (1) UK 1 KG phase 3 and HapMap reference to predict non-genotyped SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF)>1% and (2) an in-house dataset consisting of n>6000 Danish whole genome sequences to improve the prediction of variations with a MAF down to around 0.01%.21 Variants listed in the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines are currently not predicted, due to restrictions from the Danish National Ethics Committee.22 For future collaborative studies, the Ethics Committee will approve analysis of these variants on a case by case basis.

Copy number variations

Using the genotype of b-allele count and log Ratio, CNVs are called using pennCNV.23 CNVs called using <20 SNPs are excluded and the remaining CNVs are visually inspected to exclude false positives.

Statistical design

All data are stored and analysed on a specialised, secure section of the 16 000 core Danish National Supercomputer for Life Sciences—Computerome (http://www.computerome.dtu.dk). Data storage and computational analysis is performed on a protected, private cloud environment. The analysis environment is capable of dynamic scaling and has been successfully tested in a composition of over 100 servers totalling more than 300 CPUs, over 13 TB of RAM and has access to up to 5.7 PB (5700 TB) of disk space. The cluster comes with a preconfigured queuing system, possibility to run Virtual Machines and containers (eg, Docker, Singularity), a set of over 900 preinstalled tools and packages and a possibility to add GPU servers optimised for Machine Learning and specialised big memory systems (1– 8 TB of RAM).

For each hypothesis tested, a synopsis is provided including a detailed analysis plan. Information on each synopsis will be published either as link to published articles describing the results or as summary statistic on the study website: http://www.dbds.dk.

Samples

During each visit to a blood donor facility (up to four times per year for whole blood donors or up to ten times if plasma donors), every participant donates one EDTA plasma sample. At inclusion in DBDS one whole blood sample is also taken. Plasma samples taken prior to the inclusion date are stored for quality assessments and will also be accessible for future analyses. All samples are frozen within 6 hours of donation and stored in the primary collection tubes until processing.

Routine blood measurements including, for example, blood group, red and white blood cell counts, haemoglobin concentration and haematocrit are obtained at each donation. Besides routine measures, project-related measurements are available, for example, subgroups of patients are assessed for ferritin levels, infection status (Cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii and Herpes Simplex Virus), HLA-typing and other selected markers of infection (circulating cytokines, C reactive protein and so on).

General data protection and ethical issues and principles

DBDS has secured necessary permissions and approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0015) and the Scientific Ethical Committee system (M-20090237). New projects within the DBDS Genomic consortium will require additional approval by the National Committee on Health Research Ethics. DBDS will be responsible for the continued contact with, and securing future permissions from, relevant Danish authorities regarding research on DBDS samples.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design of this study.

Data availability statement

The study will adhere to the FAIR (http://datafairport.org/: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) concepts. Within this legal framework, DBDS Genomic Consortium Board can thus decide how and under which conditions the data can be shared. Generally, relevant summary data will be publicly available via repositories 3 months after acceptance for publication (H2020 open-access policy).

Findings to date

Initial quality measures that have been assessed:

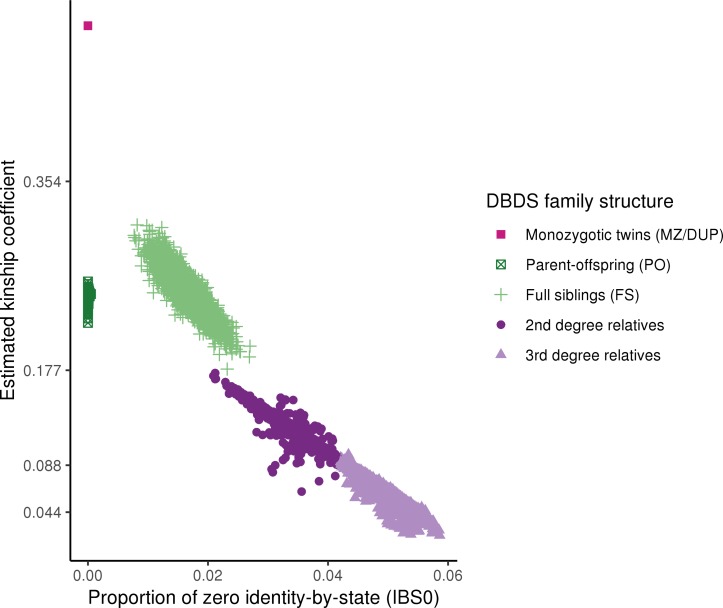

Kinship

As described, giving blood often runs in families and the heritability has been estimated to be >53%.8 It is clear from the estimated kinship based on the first batch of participants (n=85 000) (figure 1, table 2), that there is a considerable first, second and third degree relatives among the participants in the DBDS Genomic Cohort.

Figure 1.

Relationships for DBDS donors genotyped as part of the first batch(n=85 000). Each point represents a pair of related individuals and the colours indicate the degree of relatedness (‘InfType’ in KING IBD segment inference): monozygotic twins and technical duplicates (MZ/DUP) in pink (in the upper left corner), first degree relatives as parent-offspring pairs (PO, dark green) and full siblings (FS, light green), second and third degree relatives in dark and light purple, respectively. The y-axis shows the estimated kinship coefficient, defined as the probability that two alleles sampled at random (one from each individual) are identical by descent. The x-axis shows the proportion of zero identity-by-state (IBS0), defined as the proportion of SNPs at which two samples share no alleles. KING’s criteria were used to estimate the degree of relatedness (--related command in KING). We used a set of independent high-quality markers (excluding palindromic and non-autosomal markers, markers with MAF<1%, low call-rate (<99%) and markers in regions with high Linkage Disequilibrium) for the relatedness calculation. DBDS, The Danish Blood Donor Study; MAF, minor allele frequency.

Table 2.

Related pairs (third degree or closer) for batch 1 DBDS donors genotyped (n=85 000)

| Relationship | Monozygotic twins | Parent-offspring | Full siblings | Second degree | Third degree |

| Pairs | 51 | 4246 | 3309 | 4375 | 11 433 |

DBDS, The Danish Blood Donor Study.

Ethnicity

Based on ~15K overlapping SNPs from the genotyped data and the 1000 Genomes samples, we confirm the expected population structure of the DBDS cohort; most participants are of European ancestry (99%) and the following two ethnicity groups are of South Asian (0.4%) and East Asian (0.2%) ancestry, respectively. The proportion of participants with recent African ancestry is extremely low (0.002%) which is expected given the strict donor travel quarantine rules. Ethnicity was evaluated using FlashPCA2.24

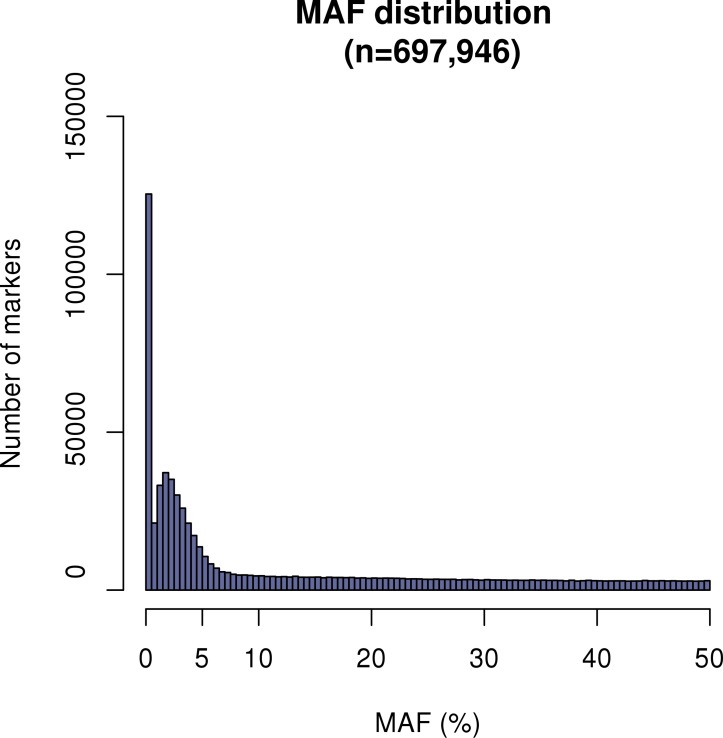

Minor allele frequencies

The distribution of the MAF shows that majority of SNPs (84%) are above 1% (figure 2) as expected, which provides solid basis for genotype imputation.

Figure 2.

MAF distribution of the genotyped SNPs prior to quality control. DBDS, The Danish Blood Donor Study; MAF, minor allele frequency; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Strength and limitations

Consecutive measurements

A unique feature of this large blood donor cohort is the ability to do consecutive assessments. In standard settings, participants are typically recruited at a baseline time-point and are invited for follow-up studies once or twice in the following years. The blood bank represents an advantage because most donors have a long-term committed relationship for blood donation and are seen one to four times annually.25 It is therefore possible to collect several yearly and consecutive biological samples and questionnaire information over decades for a large number of participants. Again, subgroups and samples from specific time-points can be used in a retrospective manner.

National-based registries

Denmark has several comprehensive national registries, which include both health information and sociodemographical measures on an individual level. The informed consent allows for combining information obtained from the DBDS participants and the national registries; the Danish National Patient Registry (since 1977), the Danish Cancer (since 1943) and Diabetes Registries (since 1992–2012), the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics (since 1994), the Civil Registration Registry (since 1968 vital status, number of children, birthplace, address, relocation and more), the Integrated Database for Labor Market Research (since 1982, eg, educational level, occupation status, income, social status and other related parameters). This facilitates retrospective, cross-sectional or prospective studies using registry-based measurements in combination with questionnaire-derived data.

Donor selection

Although DBDS participants resemble the Danish population, a few limitations in the study design may affect the generalisability of the results.1 The blood donor exclusion criteria dismiss individuals with infections or diseases that are transmittable through blood, weight below 50 kg, haemoglobin (Hb) levels below 12.9 g/L in males and 12.0 g/L in females and curious behaviours: individuals with high travel rates to countries with high risk of hepatitis and HIV, men who have sex with men, individuals who have previously worked as sex workers, those who have used intravenous substances and pregnant women. Comparing sociodemographical parameters of blood donors with that of the total Danish population, we know that very low-income and high-income individuals are underrepresented among blood donors.1 In this respect, we acknowledge that DBDS lacks coverage of certain parts of the general population in contrast to traditional population-based studies. Similarly, the population based UK Biobank study have also reported a ‘healthy volunteer’ bias.26

Discussion

The extension of the DBDS with a genomic cohort will profoundly impact the usability and empower studies on genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors that influence blood donor health. Furthermore, the study provides a unique platform that facilitates analysis of common phenotypes not otherwise found in the national health registries, disease resilience factors and interactions between genes and environment. Finally, such a large healthy cohort holds a huge potential for providing crucial information for future precision medicine initiatives and similar efforts have been started, for example, ‘All of US’ (by NIH, US). In Denmark, we have the advantage of a collection of extensive, national health registries that facilitate epidemiological studies on specific diseases/outcomes in such a large cohort. For phenotypes and symptoms not monitored systematically in these health registries, for example, lifestyle factors such as smoking habits, sleep patterns and self-perceived health, large epidemiological studies are needed but typically difficult to conduct. The DBDS Genomic Cohort can facilitate such studies. As described above, the DBDS Genomic Cohort exploits an existing blood donor platform with an extremely high participation rate (>95%), which facilitates a straightforward evaluation of donor health in large epidemiological studies. Furthermore, the electronic questionnaire platform allows for easy and fast implementation of new, targeted investigations in subgroups of the donor population. Together with outcomes from the Danish health registries and the millions of retrospective plasma samples stored in easily accessible freezers, DBDS represents a solid phenotyping platform that can be used for both cross-sectional epidemiological studies and for retrospective biomarker studies. We believe that these strengths make the DBDS Genomic Cohort a strong competitive player in the field of precision medicine.

The DBDS Genomic Cohort allows us to study gene-environment interaction that are otherwise difficult to study: testing disease development hypotheses, for example, (1) cognitive performance in interaction with genetic factors and the risk of dementia and (2) determining the contribution of genetic and environmental factors to a phenotype such as sleep pattern. One way to study this is by using multivariate regression models. As an example, Fan et al have recently portrayed an advanced example of gene-environment interaction analysis incorporating temporal and spatial considerations,27 an analysis based on data from the Danish civil registries. The DBDS Genomic Cohort is particularly valuable for studying disease resistance in individuals exposed to one or more known disease risk factors and yet do not proceed to develop the disease. One such example could be participants carrying a high load of a highly inheritable trait like psychiatric illness in the family or known genetic risk factors, who do not have psychiatric illness themselves. Last, DBDS also provides sequential storage of plasma samples, which allows for sequential blood measurements. Such measurements could be used to investigate health markers like suPAR (soluble urokinase plasminogen activating receptor) and the variation associated with the donor’s general health.28

In short, the DBDS Genomic Cohort facilitates the investigation of the impact of genomic factors on health traits and states.

Integrative analysis of different ‘omics, that is, multiomics analysis will be possible in the large DBDS Genomic Cohort, which adds tremendously to its value as a resource for studying the health of blood donors and correlation between blood related traits and states. We expect that the DBDS Genomic Cohort will contribute to discovery and validation of prodromal symptoms and biomarkers of disease, thus providing a better understanding of the disease pathologies and suggesting new drug targets.

Collaboration

We encourage scientific collaborations using the data generated in the DBDS Genetic Consortium. Published summarised data are available on request. Otherwise request of data necessitates first approval by the DBDS steering committee and if the request is considered outside the aim of DBDS, application to the national scientific ethical committee is obligatory. Additionally, material transfer and data protection agreement need to be acquired. Please visit http://www.dbds.dk.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express a special thanks to the staffs of the Danish blood banks whose continued inclusion of blood-donors into the DBDS makes this research possible.

Footnotes

TFH and KB contributed equally.

Contributors: TFH, KB and KSB conceived and planned the experiments. KB carried out the analyses. OBP, HH, HP, KN, CE, HU, PJ, TW, JO, GBEJ, MN, SA, PIJ, ES and LT contributed to cohort and research design. DW, PJC, KB and SB led to data infrastructure design. CE, KSB, MAHL, ES and MP contributed to data capture. TFH, KB and KSB contributed to the interpretation of the results. TFH, KB and KSB took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the analysis and manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: We wish to thank the Lundbeck Foundation, Denmark under Grant (R209-2015-3500 to Kristoffer Burgdorf), The Danish Administrative Regions, The Danish Blood Donor Research Foundation (Bloddonorernes Forskningsfond), Rigshospitalets Research Foundation, The Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF14CC0001 and NNF17OC0027594) and CANDY foundation (CEHEAD).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. See data sharing statement

Data sharing statement: The study will adhere to the FAIR (http://datafairport.org/: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable)concepts. Within this legal framework DBDS Genomic Consortium Board can thus decidehow and under which conditions the data can be shared. Generally, relevant summarydata will be publicly available via repositories 3 months after acceptance forpublication (H2020 open-access policy)

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Burgdorf KS, Simonsen J, Sundby A, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics of Danish blood donors. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169112 10.1371/journal.pone.0169112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Harst P, Zhang W, Mateo Leach I, et al. Seventy-five genetic loci influencing the human red blood cell. Nature 2012;492:369–75. 10.1038/nature11677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLaren CE, Garner CP, Constantine CC, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic loci associated with iron deficiency. PLoS One 2011;6:e17390 10.1371/journal.pone.0017390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka T, Roy CN, Yao W, et al. A genome-wide association analysis of serum iron concentrations. Blood 2010;115:94–6. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sørensen E, Grau K, Berg T, et al. A genetic risk factor for low serum ferritin levels in Danish blood donors. Transfusion 2012;52:2585–9. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warneken F, Tomasello M. The roots of human altruism. Br J Psychol 2009;100(Pt 3):455–71. 10.1348/000712608X379061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steele WR, Schreiber GB, Guiltinan A, et al. role of altruistic behavior, empathetic concern, and social responsibility motivation in blood donation behavior. Transfusion 2008;48:43–54. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pedersen OB, Axel S, Rostgaard K, et al. The heritability of blood donation: a population-based nationwide twin study. Transfusion 2015;55:2169–74. 10.1111/trf.13086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pedersen OB, Erikstrup C, Kotzé SR, et al. The Danish Blood Donor Study: a large, prospective cohort and biobank for medical research. Vox Sang 2012;102:271 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgdorf KS, Felsted N, Mikkelsen S, et al. Digital questionnaire platform in the Danish Blood Donor Study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2016;135:101–4. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol 2019;180 10.1111/bjd.16998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kotzé SR, Pedersen OB, Petersen MS, et al. Deferral for low hemoglobin is not associated with increased risk of infection in Danish blood donors. Transfusion 2017;57:571–7. 10.1111/trf.13931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Didriksen M, Allen RP, Burchell BJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome is associated with major comorbidities in a population of Danish blood donors. Sleep Med 2018;45:124–31. 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Didriksen M, Hansen TF, Thørner LW, et al. Restless legs syndrome is associated with increased risk of migraine. Cephalalgia Reports 2018;1:251581631878074 10.1177/2515816318780743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaspersen KA, Pedersen OB, Petersen MS, et al. Obesity and risk of infection: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study. Epidemiology 2015;26:580–9. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kotzé SR, Pedersen OB, Petersen MS, et al. Predictors of hemoglobin in Danish blood donors: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study. Transfusion 2015;55:1303–11. 10.1111/trf.13011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rigas AS, Pedersen OB, Magnussen K, et al. Iron deficiency among blood donors: experience from the Danish Blood Donor Study and from the Copenhagen ferritin monitoring scheme. Transfus Med 2019;29:23–7. 10.1111/tme.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ullum H, Rostgaard K, Kamper-Jørgensen M, et al. Blood donation and blood donor mortality after adjustment for a healthy donor effect. Transfusion 2015;55:2479–85. 10.1111/trf.13205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rigas AS, Pedersen OB, Sørensen E, et al. Frequent blood donation and offspring birth weight-a next-generation association? Transfusion 2019;59 10.1111/trf.15072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eggertsson HP, Jonsson H, Kristmundsdottir S, et al. Graphtyper enables population-scale genotyping using pangenome graphs. Nat Genet 2017;49:1654–60. 10.1038/ng.3964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2017;19:249–55. 10.1038/gim.2016.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, et al. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res 2007;17:1665–74. 10.1101/gr.6861907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abraham G, Qiu Y, Inouye M. FlashPCA2: principal component analysis of Biobank-scale genotype datasets. Bioinformatics 2017;33:2776–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burgdorf KS, Pedersen OBV, Sørensen E, et al. Extending the gift of donation: blood donor public health studies. ISBT Sci Ser 2015;10(S1):225–30. 10.1111/voxs.12119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C, et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:1026–34. 10.1093/aje/kwx246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fan CC, McGrath JJ, Appadurai V, et al. Spatial gene-by-environment mapping for schizophrenia reveals locale of upbringing effects beyond urban-rural differences. bioRxiv 2018:315820. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nielsen J, Røge R, Pristed SG, et al. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor levels in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2015;41:764–71. 10.1093/schbul/sbu118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study will adhere to the FAIR (http://datafairport.org/: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) concepts. Within this legal framework, DBDS Genomic Consortium Board can thus decide how and under which conditions the data can be shared. Generally, relevant summary data will be publicly available via repositories 3 months after acceptance for publication (H2020 open-access policy).