Abstract

Objective

Integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illness is a powerful intervention to reduce mortality. Yet, only 29% and 59% of children with fever in sub-Saharan Africa had access to malaria testing and treatment between 2015 and 2017. We report how iCCM+ based on incorporating active case detection of malaria into iCCM could help improve testing and treatment.

Design

A community-led observational quality improvement study.

Setting

The rural community of Bare-Bakem in Cameroon.

Participants

Children and adults with fever between April and June 2018.

Intervention

A modified iCCM programme (iCCM+) comprising a proactive screening of febrile children <5 years old for malaria using rapid diagnostic testing to identify index cases and a reactive screening triggered by these index cases to detect secondary cases in the community.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The proportion of additional malaria cases detected by iCCM+ over iCCM.

Results

We screened 501 febrile patients of whom Plasmodium infection was confirmed in 425 (84.8%) cases. Of these cases, 102 (24.0%) were index cases identified in the community during routine iCCM activity and 36 (8.5%) cases detected passively in health facilities; 38 (8.9%) were index cases identified proactively in schools and 249 (58.6%) were additional cases detected by reactive case detection—computing to a total of 287 (67.5%) additional cases found by iCCM+ over iCCM. The likelihood of finding additional cases increased with increasing family size (adjusted odd ratio (aOR)=1.2, 95% CI: 1.1 to 1.3) and with increasing age (aOR=1.7, 95% CI: 1.5 to 1.9).

Conclusion

Most symptomatic cases of malaria remain undetected in the community despite the introduction of CCM of malaria. iCCM+ can be adopted to diagnose and treat more of these undiagnosed cases especially when targeted to schools, older children and larger households.

Keywords: malaria, integrated community case management, active case detection, Cameroon

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first study to show the public health significance of a reactive case detection strategy in a high malaria transmission area.

The study used existing community resources but in a more targeted manner to maximise access to malaria treatment in a poor and rural community.

A small-scale study with no control arm carried out during a relatively short period and during the high transmission season, thus inclined towards overestimating the value of the intervention.

Introduction

In Cameroon, malaria-related morbidity has reduced from 40.6% in 2008 to 24.3% in 2017 while malaria proportionate mortality has reduced from 17.6% in 2000 to 12.8% in 2017.1–4 Despite this remarkable effort, malaria remains a major public health problem in Cameroon where the entire population of more than 25 million inhabitants is at risk, with 71% living in high transmission areas.5 In 2016, approximately 1.7 million malaria cases and 2637 deaths from malaria were recorded in health facilities in Cameroon. Children <5 years of age were the most affected group in whom malaria was responsible for 41% of all-cause morbidity, 55% of hospital admissions and 69.7% of all malaria-attributed deaths in 20 15.2 To reduce childhood mortality, Cameroon and her development partners began implementing integrated community case management (iCCM) of pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria in 2009 to target communities with difficult access to health services. CCM of malaria can reduce overall mortality and malaria-specific under-five mortality by 40% and 60%, respectively, and severe malaria morbidity by 53%.6 7 Yet, between 2015 and 2017, only 59% of children with fever in sub-Saharan Africa received a malaria diagnostic test and only 29% had received any antimalarial drug.8 9 In some localities of Cameroon, iCCM strategy has been reported to have increased treatment rate for malaria, increased care seeking for fever and reduced burden on healthcare facilities.10 11 However, data from a community needs assessment (CNA) conducted in 2016 in the rural community of Bare-Bakem in the Littoral Region of Cameroon indicated that malaria represented up to 80% of all-cause morbidity across health centres and that iCCM has been facing significant challenges including, low uptake inherent to its passive nature, underutilisation and attrition of trained community health workers (CHWs); prolonged and frequent stockouts of commodities for malaria diagnosis and treatment; inadequate supervision and motivation of CHWs. School children, though typically constituting the group with the highest prevalence of Plasmodium infection, have been virtually left out of this intervention despite receiving increasing attention recently.12–14 In response to these challenges that threaten to reverse the initial iCCM gains, Peace Corps Cameroon has been supporting rural communities in Cameroon to effectively fight malaria. In 2018, the Peace Corps community of Bare-Bakem introduced a proactive (PACD) and reactive case detection (RACD) approach into the existing iCCM system with the objective to reduce malaria burden by expanding access to prompt malaria case management in the community. Integrating active (proactive and/or reactive) case detection strategy with iCCM has not yet been documented in high transmission settings. We report how in this community-led project, CHW proactively searched for cases of malaria in children <5 in schools, health facilities and households; and then using index cases, they reactively detected and treated even more cases in the community by visiting the households of the sick children with confirmed malaria.

Methods

Design

A community-led quality improvement study to measure the proportion of additional Plasmodium infection detected under iCCM+ compared with iCCM alone.

Intervention site and priority setting

The intervention was carried out in the rural town of Baré, the headquarters of Baré-Bakem municipality with a population of about 20 000 inhabitants occupying a surface area of about 200 km². Bare is situated at approximately 10 km from Nkongsamba (the divisional capital) and 120 km from the coastal city of Douala (the regional capital). It has 13 neighbourhoods: Bareko, Ebouth, Axe Lourd, A, A bis, B, B bis, C, D, E, E bis, F and F bis. The locality’s low elevation and its warm and wet equatorial climate are conducive for high levels of malaria transmission. The town was host to a Peace Corps Volunteer for the period between 2016 and 2018 with the mission to support efforts to fight infant and maternal mortality, malnutrition, malaria and HIV/AIDS. On average, across all the four health facilities in Baré, malaria made up approximately 40% of all sicknesses reported in 2016. Cases of malaria can even represent up to 80% of all sicknesses during the wet season. From a CNA carried out in December 2016 and January 2017 prior to the intervention, 84% reported malaria as the most important health problem, but only 34% of respondents knew how malaria was transmitted. Eighty per cent of individuals reported first seeking care from traditional healers. The iCCM programme was introduced to respond to these needs but had its shortcomings that led to the conception and implementation of iCCM+ as a modified iCCM intervention.

Intervention description and evaluation

Integrated community management

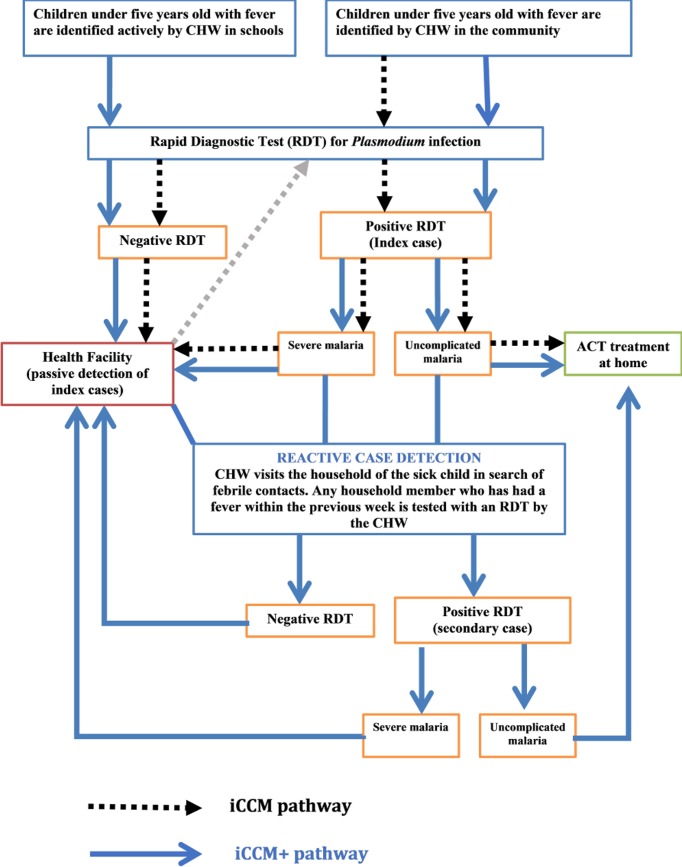

In 2016, as part of the ongoing nation-wide iCCM programme, CHW were trained, supplied and supervised to diagnose and treat children for malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea, using artemisinin-based combination therapies, oral antibiotics, oral rehydration salts and zinc. Through home visits, patients of all ages in the community are screened for the three diseases, and treatment is administered based on the results of the examination and diagnostic testing that includes malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), disease history and respiratory rate. CHW also deliver health education and promotion talks during these home visits. There are no visits to schools, and there is neither the proactive nor the RACD effort. In this study, only the malaria component of iCCM was considered (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the augmented integrated community case management of malaria (iCCM+). ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; CHW, community health worker; iCCM, integrated community case management; iCCM+, integrated community case management plus; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

Integrated community management plus

During 8 weeks of the high transmission period between April and June 2018, Baré’s six CHWs locally known in French as ‘Agent de Santé Communautaire’ conducted an active malaria case detection (ACD) involving the addition of both the PACD phase and the RACD approaches into their existing iCCM activities. In operational terms, iCCM+=iCCM+ PACD+RACD.

Before launching, the project trained 25 primary and nursery school teachers on malaria detection and on the promotion of prevention and care seeking behaviour. Each CHW was assigned to a school, and a collaborative system between teachers and CHWs working together to detect sick children was developed. Consent forms were distributed to the teachers to pass along to parents of pupils for their approval to test their children. Healthcare workers from the four health centres were also invited to the training in order to build working relations with CHWs. The CHWs had been trained repeatedly over the past years by the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) on community management of malaria, but they were briefed alongside two supervisors on the specificities of this project. One supervisor was in charge of correct data collection, while the other inspected schools and visited households to ensure completeness of field work.

PACD was undertaken in 12 primary and nursery schools, 4 health centres and 13 community neighbourhoods on a weekly basis. Each week on a Thursday, CHWs visited assigned schools and health centres to locate febrile children. On arriving at their schools, the trained teachers indicated the pupils <5 who had a fever in a recent week. Health workers similarly helped to identify febrile children admitted in health facilities. Children with fever were identified and tested at no cost for Plasmodium infection using RDTs approved and supplied by the NMCP. Those tested positive for malaria were named as ‘index cases’ and were further classified as either uncomplicated or severe malaria. Uncomplicated malaria cases were immediately treated with amodiaquine+artesunate, the first-line artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) recommended and supplied by the NMCP. Severe cases and RDT-negative cases were referred to health facilities for further investigation and management as per the NMCP guidelines. If a febrile child was absent from school the day the CHW arrived, the teacher would tell the CHW where the child lives. The CHW then visited the household to identify and test the sick child. In the community, however, CHW continued to identify febrile children as per the conventional iCCM guidelines.

As malaria cases tend to cluster geographically and temporally,15–18 CHWs who also cluster and work in the neighbourhoods in which they live, then proceeded with the RACD method to visit the home of an index case. In the households, they made a list of all persons resident in the household (contacts of the index case), identified and tested those who had a fever in the past week. Those tested positive for malaria RDT were named as ‘secondary cases’ and were also classified and treated or referred to the nearest health centre in a similar way like the index case as illustrated in figure 1.

Data were collected using paper registers and later transcribed into a Microsoft Excel electronic database available as a online supplementary file 1. Data collected from the index case during PACD included age, sex, place of residence, presence of fever, date of onset of fever, date and location seen by a CHW, results of RDT for malaria, severity of malaria and treatment received. During household visits, the same data were collected from febrile contacts in addition to data pertaining to household size, long-lasting treated bed nets ownership and current usage. Health facility malaria surveillance registers and CHW registers were used as sources to abstract data on malaria cases notified between 2015 and 2018.

bmjopen-2018-026678supp001.pdf (589.6KB, pdf)

Data analyses were performed using Stata V.14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to plot curves. The data set was checked for logical inconsistencies, invalid codes, omissions and improbable data by tabulating, summarising, describing and plotting variables, depending on their nature. Missing observations were systematically excluded.

The value of iCCM+ over iCCM alone was measured by the proportion of additional cases detected.

To describe similarities or differences between index and secondary cases, summary statistics were presented as proportions for categorical variables, as means and SDs for normally distributed continuous variables and as medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables with a skewed distribution. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for small samples, as appropriate. For continuous variables, mean differences between index cases and contacts were assessed using Student’s t-test. Associations between exposure variables and the likelihood of finding a contact were evaluated by a univariate logistic regression model; crude odd ratios and 95% CIs were reported. Subsequently, factors associated with the odds of finding a contact in the univariate analysis at a significance level <5% were included in a multiple logistic regression model with mixed effects to account for the variability in CHW performance. Backward elimination based on a p value <0.05 was used to retain variables that were independently associated with contact tracing; the corresponding adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CIs for the final model were reported.

Patient and public involvement statement

As a community-led project, the public and patients were involved in the project planning, implementation and data collection.

Individual and parental consent was sought and all information was anonymised and deidentified prior to analysis. An information letter was sent to parents and local administrations, and was announced in community meeting or worshipping places.

Results

Detection and management of cases

At the end of the 3-month pilot study, we screened a total of 501 febrile patients of whom Plasmodium infection was confirmed in 425 (overall test-positivity of 84.8%) including 176 index cases with a mean age of 3.4±0.1 years who triggered a further screening by RACD of 249 contacts of mean age 19.2±1.2 years (table 1). On average, index cases were reached within 2.4±0.2 days after onset of fever. Index cases were mostly boys (60.8% vs 49.8%, p=0.025) while secondary cases were mostly girls <5 years but no gender specificity among older secondary cases. The RDT positivity for malaria was very high in both the index (83.4%) and the secondary cases (85.9%). Of these 425 confirmed malaria cases, 354 (83.3%) were classified as uncomplicated malaria cases who received ACT immediately from the CHW. The 71 cases who did not receive immediate ACT were classified as severe malaria cases who were referred to the nearest health centre for further management.

Table 1.

Characteristics of index and secondary cases of malaria detected between April and June 2018

| Characteristics | Index cases (n=176) |

Secondary cases (n=249) |

P value of the difference between the groups of cases |

| Reactive cases found per index case source | |||

| School | 38 (21.6) | 50 (20.1) | |

| Health facility | 36 (20.4) | 24 (9.6) | |

| Community | 102 (58.0) | 175 (70.3) | |

| Total | 176 (100.0) | 249 (100.0) | 0.004 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 107 (60.8) | 124 (49.8) | |

| Female | 69 (39.2) | 125 (50.2) | |

| Total | 176 (100) | 249 (100) | 0.025 |

| Age, mean (SD) years | 3.4 (0.1) | 19.2 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Immediate malaria treatment, n (%) | |||

| ACT | 142 (80.7) | 212 (85.1) | |

| No ACT | 34 (19.3) | 37 (14.9) | |

| Total | 176 (100) | 249 (100) | 0.225 |

| Referred to health facility, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 34 (19.3) | 37 (14.9) | |

| No | 142 (81.7) | 212 (85.1) | |

| Total | 176 (100) | 249 (100) | <0.001 |

| Household size, mean (95%CI) | 6.4 (6.2 to 6.6) | ||

| Household LLIN ownership, mean (95%CI) | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.6) | ||

| LLIN coverage per household member (95%CI) | 0.38 (0.36 to 0.40) | ||

| LLIN in use per household member (95%CI) | 0.34 (0.32 to 0.36) | ||

ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal nets.

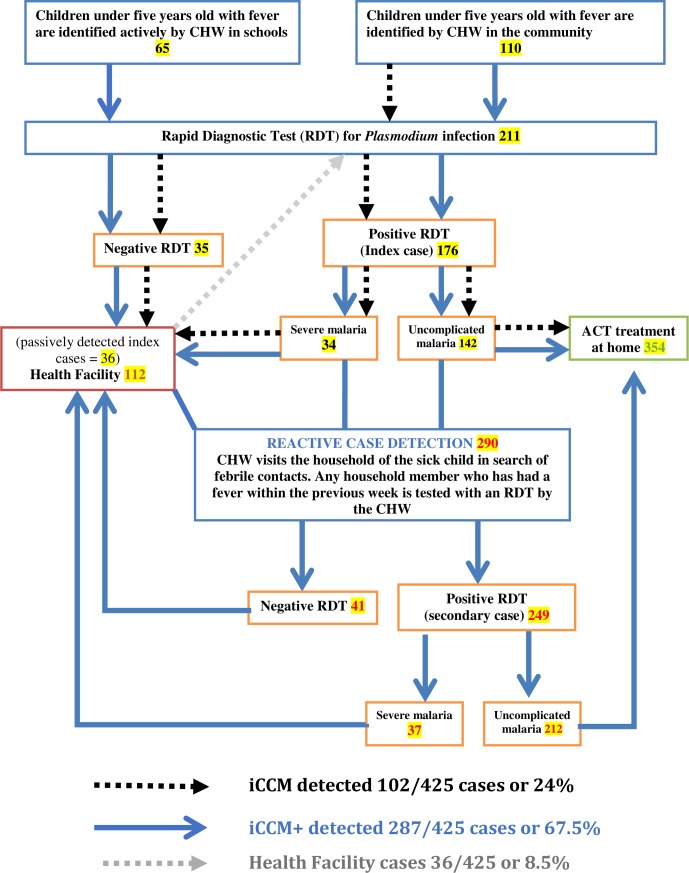

Proactive and reactive case detection of confirmed malaria

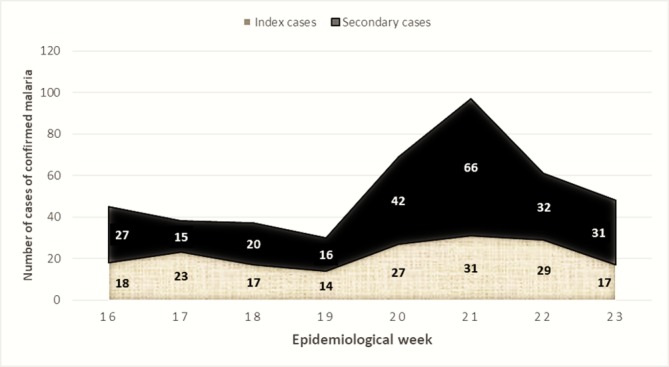

During the RACD triggered by 176 index cases of confirmed malaria in children under five, 132 (75%) of these index cases investigated led to at least one additional case and a total of 249 secondary cases identified from 290 febrile contacts within 176 households visited. There were approximately six persons on average per household with a bed net ownership of about two long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) per household leading to a bed net coverage of about one LLIN for three persons. After a lag phase during the first half of the project, the number of cases detected increased sharply over the second half before returning to the initial stable level (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trend in the number of cases of confirmed malaria between April and June 2018.

Of all the 425 confirmed cases, 38 (8.9%) were index cases identified proactively in schools and led to find 50 (11.8%) more cases; 36 (8.5%) were index cases located in health facilities and led to a further 24 (5.6%) cases and 102 (24.0%) were index cases identified during routine iCCM activity and led to 175 (41.2%) additional cases showing the value of RACD over iCCM alone (figure 2). Overall, iCCM+ identified 287 of the 425 cases, thus indicating that the ongoing iCCM must have been improved by 67.5% to detect malaria cases in the community (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of cases detected and treated during iCCM and iCCM+. ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; CHW, community health worker; iCCM, integrated community case management; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

During 12 weeks in April, May and June in 2017, CHWs detected 238 cases of malaria at a rate of ~20 cases per week. But during our 8-week project across April, May and June in 2018, the CHWs detected 365 cases of malaria at a rate of ~45 cases per week computing to a 125% increase from 2017 during the same transmission season.

The odds of finding a secondary case by RACD increased by 70% if the index case was 1 year younger than the secondary case (aOR=1.7, 95% CI: 1.5 to 1.9) and by 20% if a household size increased by one person (aOR=1.2, 95% CI: 1.1 to 1.3). Though RACD was likely to find female cases, the evidence to support gender discrimination was rejected in the multiple regression model in table 2 (aOR=1.2, 95% CI: 0.7 to 2.1).

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression model of factors associated with secondary case detection (n=425)

| Factor | Number of confirmed secondary cases, n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 124 (53.7) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 125 (64.4) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | 0.024 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | 0.477 |

| Additional 1year of age | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | <0.001 | |

| Additional one household member | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 0.015 | |

Discussion

In this small-scale quality improvement study, we sought to demonstrate in a high transmission area, the feasibility of embedding both the PACD and RACD strategies into iCCM in order to maximise malaria case detection and prompt treatment. The study has indicated that iCCM+ increased the proportion of persons diagnosed and treated for Plasmodium infection by approximately 67.5%. The study has also confirmed that the burden of malaria lies in the community with only the tip of the iceberg seen in health facilities. While iCCM was introduced to respond to this challenge, it was currently underperforming in this rural setting. This project has suggested that iCCM can be adapted to achieve optimal results. While on one hand it may appear obvious that the malaria component of iCCM can be adapted to or opt for a PACD strategy, implementing RACD in a high transmission setting on the other hand may seem experimental or even controversial to some extent. This is because RACD is a surveillance approach recommended in low transmission or pre-elimination settings to disrupt transmission and is thought to be inefficient and infeasible in high transmission settings. Conversely, RACD may also waste time and money when cases are few and sporadic.19–22 Therefore, the choice of RACD as an approach depends on the objective to be attained, the proportion of cases it can detect and the resources needed. Our project was feasible and efficient because our aim was not to eliminate malaria but to detect and treat the maximum possible number of cases during a high transmission season when the proportion of cases is highest using resources already made available for iCCM in a rural setting where access to health services is limited. The extra resource needed is the time to visit schools, health facilities and households. CHWs told us that by conducting only a 1 day visit per week to these facilities and only to households of index cases was more productive and made them more useful in their community. This strategy was not much different from what they were doing before, just a more targeted approach: targeting schools, targeting households of index cases and targeting high transmission season when fever is likely to be caused by a Plasmodium infection as confirmed in this study where RDT was positive in 85% of persons screened for fever and with a high probability of 75% that every index case led to at least one secondary case. Beyond CHW job satisfaction, teachers also expressed their satisfaction and were of great support in detecting fever or a history of fever among their pupils. Moreover, we found that teachers were far more likely to help CHW finding the households of sick children than healthcare workers. We thus strongly believe that RACD can be both feasible and efficient in a high transmission setting to maximise clinical case management. Consequently, we recommend that PACD and RACD become part of the ongoing iCCM strategy in Cameroon as an approach to optimise case detection. Yet, incorporating PACD and RACD into iCCM will entail building a strong collaboration among CWH, healthcare workers and teachers. Such a partnership already exists between the ministries of health and education in Cameroon in their concerted effort to fight neglected tropical diseases specifically soil-transmitted helminthiasis in school children.23 The recurrent problem of stockouts of commodities will need to be resolved by the NMCP, and field monitoring and supervision should become regular by iCCM programme coordination. Resolving these issues of multisector collaboration, delivery of commodities and field coordination were crucial as bottlenecks and explain in part why progress was slow in the first half of the project. In response to the breakdown in the delivery of commodities, the regional office for the NMCP is now distributing these commodities to health facilities and thus offsetting the transportation hurdles faced by the latter to purchase and pick them up from their regional head offices of NMCP. Moreover, under the ongoing performance-based financing system, health facilities are becoming more and more autonomous and can get their commodities from local authorised outlets.

This study has further indicated that, while index cases were likely to be boys, RACD was likely to find girls and women in univariate analysis though such claims were not supported by evidence from multivariate analysis. Boys make up the majority of school children in Cameroon especially in the rural areas, and this might be a reflection of this observation.24 However, it is plausible that gender norms and values that determine the division of labour, leisure patterns, pregnancy and sex-segregation of sleeping arrangements may lead to different patterns of exposure to mosquitoes for men and women.24–26

Secondary cases were likely to be older than index cases and to be located in larger households of the index case. Given that we purposely targeted children <5 years, it became obvious that we may likely find more of older children and adults as contacts. Clustering of cases has previously been demonstrated in households of the contacts, and malaria eradication is thought to be feasible when household size drops below four persons.27 28 The average household size in this study was six persons, thus explaining while it was very likely to find more cases in the community during RACD.

This study had some limitations so that the results should be interpreted with caution. There was no control arm to clearly distinguish iCCM+ from iCCM intervention areas. A randomised community trial may be recommended as a solution. The duration and period of the study was limited to only 3 months and to the first half of the wet season. We could not therefore account for neither seasonality in malaria transmission nor account for sustainability throughout the year. Older children and adults were not included as index cases, thus creating an outright difference between index and secondary cases. This must have led to an overestimation of the value of RACD in this field study because in routine practice, however, adults would be index cases as well. Targeting school children for malaria treatment must have been a laudable effort but older school children were also left out as index cases though they constitute a group with a higher Plasmodium infection prevalence than in the targeted younger age group.12 However, these children were among those screened in the community. We did not measure the effect of this strategy on the pneumonia and diarrhoea components of iCCM but we believe that being an integral part of the package of interventions, these two components were likely to have been improved as well. We did not attempt to measure effect on malaria transmission as most studies have done.

Conclusion

This study has shown that most symptomatic cases of malaria remain undetected in the community despite the introduction of integrated community management of malaria. Schools are an important portal to locate children with undiagnosed malaria. Active case detection based on PACD and RACD approaches is feasible in a high transmission setting and has been shown to enhance in a synergistic manner the efficiency of iCCM of malaria. We recommend that national malaria control programmes adopt and implement this modified form of iCCM in similar settings to diagnose and treat more malaria cases in our communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Justin Lowe who was a major actor in community mobilisation and awareness raising. We wish to sincerely thank all the community volunteers, health workers, teachers, interns and the people of Bare-Bakem for their support and active participation and collaboration.

Footnotes

Contributors: TDW and CEB: conception, design and implementation, data collection, analysis and interpretation. CEB: drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the National Ethics Review Board of Cameroon, Peace Corps Cameroon and local administrative and health authorities. Verbal consent was obtained from household members after making public announcements and providing an information leaflet to explain the objectives of the project.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available as a supplementary file.

Author note: CEB: Public Health Physician, Chief of Medical Centre of Bare-Bakem. TD’AW: Community Health Educator, Peace Corps Cameroon.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

References

- 1. Minsante. La cérémonie officielle de commémoration de la 10ème Journée Mondiale de lutte contre le paludisme. Yaounde: Ministere de la Sante Publique du Cameroun, 2017:2. [Google Scholar]

- 2. UNICEF. En finir avec le paludisme pour de bon Nous sommes une génération qui peut éliminer le paludisme. Yaounde: United Nations Children Fund, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Country Brief Malaria In Cameroon. Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. MISANTE. 3eme Campagne nationale de distribution gratuite de masse des moustiquaires impregnees a longue duree d’action (milda), propos liminaire de la communication gouvernementale de monsieur le ministre de la sante publique. Yaounde: Ministere de la Sante Publique du Cameroun, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO. Cameroon Malaria Profile in 2015 Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/country-profiles/profile_cmr_en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 18 Jun 2017).

- 6. Kidane G, Morrow RH. Teaching mothers to provide home treatment of malaria in Tigray, Ethiopia: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:550–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02580-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sirima SB, Konaté A, Tiono AB, et al. Early treatment of childhood fevers with pre-packaged antimalarial drugs in the home reduces severe malaria morbidity in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health 2003;8:133–9. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. RBMP. A Decade of Partnership and Results. Progress and Impact Series. Geneva: Roll Back Malaria Partnership, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO. World malaria report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarrah Z, Gilmartin C, Collins D. The Cost of Integrated Community Case Management in Nguelemendouka and Doumé Districts. Cameroon 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller J. Community Case Management in Cameroon. Washington: Population Services International, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nankabirwa J, Brooker SJ, Clarke SE, et al. Malaria in school-age children in Africa: an increasingly important challenge. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:1294–309. 10.1111/tmi.12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathanga DP, Halliday KE, Jawati M, et al. The high burden of malaria in primary school children in southern Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;93:779–89. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clarke SE, Rouhani S, Diarra S, et al. Impact of a malaria intervention package in schools on Plasmodium infection, anaemia and cognitive function in schoolchildren in Mali: a pragmatic cluster-randomised trial. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000182 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stresman GH, Kamanga A, Moono P, et al. A method of active case detection to target reservoirs of asymptomatic malaria and gametocyte carriers in a rural area in Southern Province, Zambia. Malar J 2010;9:265 10.1186/1475-2875-9-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerardin J, Bever CA, Hamainza B, et al. Optimal Population-Level Infection Detection Strategies for Malaria Control and Elimination in a Spatial Model of Malaria Transmission. PLoS Comput Biol 2016;12:e1004707 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parker DM, Matthews SA, Yan G, et al. Microgeography and molecular epidemiology of malaria at the Thailand-Myanmar border in the malaria pre-elimination phase. Malar J 2015;14:198 10.1186/s12936-015-0712-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Branch O, Casapia WM, Gamboa DV, et al. Clustered local transmission and asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria infections in a recently emerged, hypoendemic Peruvian Amazon community. Malar J 2005;4:27 10.1186/1475-2875-4-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aidoo EK, Afrane YA, Machani MG, et al. Reactive case detection of Plasmodium falciparum in western Kenya highlands: effective in identifying additional cases, yet limited effect on transmission. Malar J 2018;17:111 10.1186/s12936-018-2260-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hustedt J, Canavati SE, Rang C, et al. Reactive case-detection of malaria in Pailin Province, Western Cambodia: lessons from a year-long evaluation in a pre-elimination setting. Malar J 2016;15:132 10.1186/s12936-016-1191-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Searle KM, Hamapumbu H, Lubinda J, et al. Evaluation of the operational challenges in implementing reactive screen-and-treat and implications of reactive case detection strategies for malaria elimination in a region of low transmission in southern Zambia. Malar J 2016;15:412 10.1186/s12936-016-1460-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Eijk AM, Ramanathapuram L, Sutton PL, et al. What is the value of reactive case detection in malaria control? A case-study in India and a systematic review. Malar J 2016;15:67 10.1186/s12936-016-1120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Kamwa Ngassam RI, Sumo L, et al. Mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in the regions of centre, East and West Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1553 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Atemnkeng JT, Noula AG. Gender and increased access to schooling in cameroon: A marginal benefit incidence analysis. Journal of International Women’s Studies 2011;12:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- 25. TheGlobalFund, Malaria, Gender and Human Rights: Technical brief Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gender WHO. health and malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huldén L, McKitrick R, Huldén L. Average household size and the eradication of malaria. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2014;177:725–42. 10.1111/rssa.12036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hulden L. Household size explains successful malaria eradication. Malar J 2010;9(S2):O18 10.1186/1475-2875-9-S2-O18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026678supp001.pdf (589.6KB, pdf)