Abstract

Objective

Although there is accumulating evidence regarding multimorbidity in Western countries, this information is very limited in Asian countries. This study aimed to estimate population-based, age-specific and gender-specific prevalence and trends of multimorbidity in the Taiwanese population.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study based on claims data (National Health Insurance Research Database, Taiwan).

Participants

The participants included a subset of the National Health Insurance Research Database, which contains claims data for two million randomly selected beneficiaries (~10% of the total population) under Taiwan’s mandatory National Health Insurance system.

Outcome measurements

The prevalence of multimorbidity in different age groups and in both sexes in 2003 and 2013 was reported. We analysed data on the prevalence of 20 common diseases in each age group and for both sexes. To investigate the clustering effect, we used graphical displays to analyse the likelihood of co-occurrence with one, two, three, and four or more other diseases for each selected disease in 2003 and 2013.

Results

The prevalence of multimorbidity (two or more diseases) was 20.07% in 2003 and 30.44% in 2013. In 2013, the prevalence varied between 5.21% in patients aged 20–29 years and 80.96% in those aged 80–89 years. In patients aged 50–79 years, the prevalence of multimorbidity was higher in women than in men. In men, the prevalence of chronic pulmonary disease and cardiovascular-related diseases was predominant, while in women the prevalence of osteoporosis, arthritis, cancer and psychosomatic disorders was predominant. Co-occurring diseases varied across different age and gender groups.

Conclusions

The burden of multimorbidity is increasing and becoming more complex in Taiwan, and it was found to vary across different age and gender groups. Fulfilling the needs of individuals with multimorbidity requires collaborative work between healthcare providers and needs to take the age and gender disparities of multimorbidity into account.

Keywords: disease burden, multimorbidity, national health insurance research database

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first nationwide study conducted in Taiwan to assess the age- and gender-specific burden and complexity of multimorbidity and was carried out between 2003 and 2013.

Multimorbidity was defined by existing methods with consideration of geographical or ethnic discrepancies between Western and Asian countries.

We identified multimorbidity based on the diagnoses recorded at outpatient or inpatient visits; however, only up to three or five diagnoses were allowed to be recorded in each outpatient or inpatient visit in the National Health Insurance Research Database. Therefore, the prevalence of multimorbidity may be underestimated.

Introduction

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic health conditions in the same person at the same time, has become a significant challenge to healthcare systems worldwide. Previous studies have reported multimorbidity to be associated with worse clinical outcomes, a poorer quality of life and increased medical expenditures at the individual level.1 2 At the national level, multimorbidity also incurs significant social and economic burdens due to complex health and welfare demands and the associated costs of caring for individuals with multimorbidity.1 2 These demands are expected to increase as societies age, as the prevalence of multimorbidity increases with age.3 Nevertheless, effective strategies to manage multimorbidity remain elusive. This may be due to the single-disease paradigm in the current clinical setting, which may result in fragmented care for patients who manifest multimorbidity.

To manage multimorbidity, it is necessary to measure the burden of multimorbidity, but the phenomenon of multimorbidity is not well understood. A simple count of diseases in each patient, either through self-reporting4 or through extracting information from electronic medical records using lists of diagnostic codes,5–8 has been the most common approach. The extrapolation of the abovementioned studies, however, is difficult due to several limitations. First, most of these estimates came from selected medical institutions3 9–12 or are limited to the specific population such as the elderly.3 Some studies used a survey to ascertain the prevalence of multimorbidity in patients who visited their general practitioners.13 14 However, population-based estimates are usually very limited. Second, the lists of diagnoses differ substantially between studies.6 15 16 To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no single set of codes that have been consistently used to identify patients with multimorbidity. Third, the prevalence of multimorbidity in Asian countries is very limited while the prevalence of multimorbidity may vary ethnically or geographically. Based on two systematic reviews conducted by Pati et al 17 and Hu et al,18 as well as on other studies,19–21 the available evidence of multimorbidity in Asian countries is limited to specific areas in one country19–21 (ie, no population-based data were available). Evidence is also limited by sample size (mostly including only hundreds of people)19–21 and by the method used to measure multimorbidity (most studies used self-reported data). Similarly, previous studies have mainly focused on the prevalence of multimorbidity in the elderly.17 18 20 In addition, most of the existing studies were cross-sectional, one-time measurements of the prevalence of multimorbidity17 18 20 and did not investigate the burden of multimorbidity over time.

To fill the current knowledge gap, this study aimed to estimate population-based age- and gender-specific prevalence and trends of multimorbidity using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

Methods

Data sources

This population-based, cross-sectional study was conducted using administrative claims data from Taiwan’s NHIRD. The NHIRD is a nationwide claims-based database comprising anonymous eligibility and enrolment information, as well as claims for outpatient visits, admissions, procedures and prescription medications, of more than 99% of the entire population (23 million) of Taiwan.22

We used a subset of the NHIRD that contained claims data for two million randomly selected beneficiaries to create an 11-year (2003–2013) panel of claims for analysis. In this study, we used two subsets of the NHIRD—the 2005 and 2010 Longitudinal Health Insurance Databases (LHID)—as our data source. These two data sets were made up of claims data on one million beneficiaries that were randomly sampled by the National Health Research Institute (NHRI), Taiwan. The one million beneficiaries in LHID 2005 were randomly selected from the 2005 Registry for Beneficiaries of the NHIRD, which includes registration data of approximately 25.68 million beneficiaries of the National Health Insurance (NHI) programme during the year 2005. The one million beneficiaries in LHID 2010 were randomly selected from the 2010 Registry for Beneficiaries of the NHIRD, which includes registration data of approximately 27.38 million beneficiaries of the NHI programme during the year 2010. According to the statistics provided by the NHRI, there were no significant differences in the gender distribution between patients in the LHID 2005 subset and the original NHIRD (χ2=0.008, df=1, p=0.931) or between those in the LHID 2010 subset and the original NHIRD (χ2=0.067, df=1, p=0.796).23 Therefore, the two subsets were thought to be representable to the original NHIRD, and the results obtained suggested generalisability to the whole Taiwanese population. The sampling and data linkage process is provided in online supplementary figure S1.

bmjopen-2018-028333supp001.pdf (413.6KB, pdf)

A total of two million individuals, which comprised approximately 10% of the total population in Taiwan, constituted the study population.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design and conduct of this study.

Identification of common diseases

We defined study subjects as patients who had diagnoses of 20 common diseases at outpatient or inpatient visits during the study period. To ensure the specificity of every disease, only those who had at least three outpatient or one inpatient claim records of that specified diagnosis code in 1 year were considered as having that specified disease. This algorithm was adopted from many published studies that have used NHIRD to identify comorbidities.24–26 For example, one individual must have at least three different visits for hypertension (eg, 1 March, 2 May and 15 July 2003) to be considered as having hypertension in that year. The same algorithm was applied to other diseases. Therefore, if this person also had at least three different visits for diabetes mellitus, then he or she was defined as having two diseases (multimorbidity) in that year. Based on our algorithm, the diseases we selected in this study were chronic diseases.

Similar with most previous studies focusing on multimorbidity, we also specified multimorbidity in this study as patients who concurrently suffered from two or more of the 20 common diseases. The 20 common diseases included hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary syndrome, cardiac dysrhythmias, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, liver disease, dementia, other neurological disorders, digestive disorders, osteoporosis, arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis), anxiety dissociative and somatoform disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, and cancer. The detailed set of diagnostic codes regarding the definition of these common diseases is presented in online supplementary table S1. These diseases were selected based on their disease burden, which impacts the whole of society regarding their considerable cost, the requirement for long-term care, reduced health-related quality of life, hospitalisation or death, as illustrated in previous studies.6 25 27 Three epidemiologists with clinical and research expertise in chronic diseases and multimorbidity took part in the discussions of the literatures regarding the existing definitions of chronic diseases across scientific papers. There was a lack of consensus over what diseases should be included in the definition of multimorbidity. Therefore, in the current study, we included all those diseases that were included in two previous multimorbidity studies,6 27 as well as those from a Taiwanese study (our previous study that involved a geriatric specialist) evaluating the association between multimorbidity and unplanned hospitalisations, admission to intensive care units and mortality.25 In this way, we believed the list of diseases we adopted to define multimorbidity was capable of reflecting the disease burden of the Taiwanese population.

Statistical analysis

We reported descriptive data on the prevalence of multimorbidity in different age groups (categorised into the following eight groups: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90+ years) and both sexes (men and women) in the years 2003 and 2013 (annual point prevalence). Χ2 tests were used to compare prevalences in the years 2003 and 2013. The prevalence of multimorbidity was calculated by dividing the number of patients afflicted with multimorbidity by the population size in each age group regarding the degree of multimorbidity (grouped into 2, 3, 4 and 5+). We further analysed data on the prevalence of each of the 20 common diseases in each age group and sex. The individual prevalence was the estimated fraction (percentage, %), with the number of patients with each disease in each age group and sex as the numerator and the population size of each age group and sex as the denominator.

To analyse the clustering effect, we used graphical displays of the likelihood of co-occurrence with one, two, three, and four or more other diseases for each selected disease in the years 2003 and 2013. The likelihood was the estimated proportion of the number of patients suffering from the same disease with concurrent one, two, three, and four or more other diseases divided by the number of patients with a specific disease. We also used graphics to illustrate differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity and the clustering effect between both sexes and among age groups in 2003 and 2013. All data in this study were analysed using the Python programming language with Mongo database software, V.3.6.4 and V.4.0.2.

Results

In general, the prevalence of at least one of the 20 common diseases was 37.23% in 2003, and an approximately 10% increase was observed in 2013 (48.97%; table 1). The prevalence of at least one disease ranged from 16.74% in patients aged 20–29 years to 78.05% in those aged 80–89 years in 2003. In 2013, the prevalence varied between 19.85% in patients aged 20–29 years and 92.01% in those aged 80–89 years. Increases in the prevalence of at least one disease from 2003 to 2013 were observed in all age groups (table 1, online supplementary figure S2). Regarding multimorbidity, the increasing prevalence across all age groups and the different intensities of multimorbidity are of great concern. For instance, the prevalence of 3 of the 20 common diseases was 30.39% in patients aged 60–69 years in 2003, and an approximately 7% increase in prevalence was observed in 2013. In patients aged 90 years or more, the increase was even more significant. Compared with the prevalence of three diseases in 2003 (33.04%; table 1, online supplementary figure S2), in 2013 it had nearly doubled (66.52%; table 1, online supplementary figure S2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of multimorbidity in Taiwan by number of common diseases†, age group and year

| 2003 | ||||||

| Age group | Taiwanese population | Prevalence of at least one disease (%) | Prevalence of multimorbidity, by degree of multimorbidity (%) | |||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ | |||

| 20–29 | 285 406 | 16.74 | 4.01 | 1.15 | 0.36 | 0.12 |

| 30–39 | 273 713 | 24.09 | 8.04 | 2.86 | 1.03 | 0.37 |

| 40–49 | 269 568 | 35.91 | 16.01 | 7.08 | 2.92 | 1.12 |

| 50–59 | 175 456 | 51.70 | 30.15 | 16.49 | 8.00 | 3.57 |

| 60–69 | 114 876 | 66.52 | 47.08 | 30.39 | 17.13 | 8.70 |

| 70–79 | 74 756 | 77.86 | 62.40 | 45.66 | 29.10 | 16.75 |

| 80–89 | 20 002 | 78.05 | 64.32 | 48.74 | 32.39 | 19.58 |

| 90+ | 1946 | 62.23 | 45.68 | 33.04 | 21.12 | 12.69 |

| All | 1 215 723 | 37.23 | 20.07 | 11.40 | 6.09 | 3.07 |

| 2013 | ||||||

| Age group | Taiwanese population | Prevalence of at least one disease (%) | Prevalence of multimorbidity, by degree of multimorbidity (%) | |||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ | |||

| 20–29 | 245 613 | 19.85* | 5.21 | 1.49 | 0.47 | 0.15 |

| 30–39 | 295 797 | 30.49* | 11.18 | 4.10 | 1.55 | 0.60 |

| 40–49 | 277 889 | 43.45* | 21.76 | 10.08 | 4.35 | 1.83 |

| 50–59 | 272 719 | 59.90* | 37.75 | 20.87 | 10.24 | 4.71 |

| 60–69 | 173 213 | 75.39* | 56.84 | 37.49 | 21.74 | 11.70 |

| 70–79 | 102 826 | 87.53* | 74.64 | 57.04 | 38.44 | 23.60 |

| 80–89 | 52 978 | 92.01* | 82.64 | 68.10 | 49.71 | 33.06 |

| 90+ | 8492 | 90.44* | 80.96 | 66.52 | 48.39 | 32.54 |

| All | 1 429 527 | 48.97* | 30.44 | 18.61 | 10.73 | 5.94 |

*P<0.05 compared with prevalence in 2003 using Χ2 tests.

†Hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary syndrome, cardiac dysrhythmias, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, liver disease, dementia, other neurological disorders, digestive disorders, osteoporosis, arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis), anxiety dissociative and somatoform disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, and cancer.

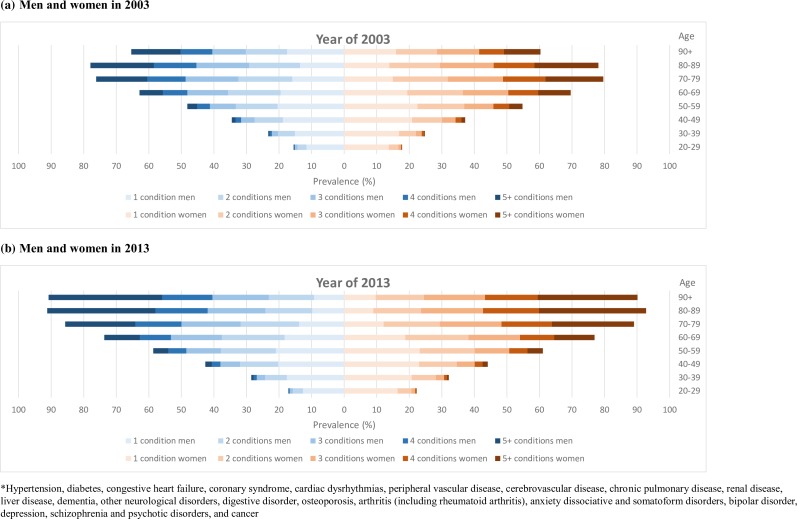

A dramatic increase in the prevalence of multimorbidity from 2003 to 2013 was found for all age groups, especially in those aged 90 years or more, for both men and women (figure 1). Patterns of sex differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity were similar between 2003 and 2013. Specifically, the prevalences of multimorbidity were comparable between men and women in patients aged 49 years or younger. In patients aged between 50 and 79 years, however, the prevalence of multimorbidity was higher in women than in men. In patients aged 80–89 years, the sex difference in the prevalence of multimorbidity was subtle. In patients aged 90 years or more, the prevalence of multimorbidity was much higher in men than in women (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of multimorbidity in Taiwan by number of common diseases*, sex, age group and year. (A) Men and women in 2003. (B) Men and women in 2013.

The prevalence of each of the 20 common diseases is presented in table 2. The prevalence of all 20 diseases remained comparable or increased in all age groups between the years 2003 and 2013. A significantly increased prevalence was observed for cancer, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, and several cardiovascular-related diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, cardiac dysrhythmias and peripheral vascular disease. The most frequently observed diseases in the Taiwanese population consisted of hypertension, other neurological disorders, digestive disorders and arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis). Over half the patients greater than 70 years in 2013 were afflicted with hypertension, and nearly one-third of those suffered from other neurological disorders, digestive disorders or arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis). Although the prevalence of cancer and dementia was generally low in Taiwan, the disease burden caused by these two diseases cannot be overlooked. Nearly one-fifth of patients aged 90 years or older were affected by dementia, and nearly one-sixth of patients aged 80 years or older were afflicted with cancer in 2013. Additionally, there was a striking increasing trend in the prevalence of these two diseases in older patients.

Table 2.

Prevalence of 20 common diseases in Taiwan, by age group and year

|

Disease |

Year |

Patients with condition, n (prevalence, %) | Prevalence of each disease, by age group (%) | |||||||

| 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | 90+ | |||

| Hypertension | 2003 | 126 651 (10.42) | 0.22 | 1.38 | 6.31 | 17.11 | 29.91 | 42.36 | 43.26 | 28.78 |

| 2013 | 260 198 (18.20)* | 0.43 | 2.38 | 9.54 | 22.91 | 39.64 | 55.39 | 61.71 | 56.64 | |

| Diabetes | 2003 | 56 627 (4.66) | 0.20 | 0.77 | 3.00 | 8.51 | 14.04 | 16.31 | 12.51 | 5.86 |

| 2013 | 126 991 (8.88)* | 0.35 | 1.27 | 4.50 | 11.47 | 21.10 | 26.39 | 25.23 | 18.38 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2003 | 44 622 (3.67) | 0.06 | 0.38 | 1.80 | 5.35 | 10.43 | 17.25 | 19.95 | 15.88 |

| 2013 | 71 026 (4.97)* | 0.09 | 0.45 | 1.87 | 4.99 | 10.10 | 17.19 | 24.78 | 28.24 | |

| Coronary syndrome | 2003 | 35 539 (2.92) | 0.04 | 0.25 | 1.19 | 3.98 | 8.75 | 14.82 | 16.05 | 11.20 |

| 2013 | 60 367 (4.22)* | 0.05 | 0.27 | 1.43 | 4.19 | 9.38 | 15.29 | 19.72 | 18.86 | |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 2003 | 14 337 (1.18) | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 1.47 | 2.89 | 5.24 | 6.67 | 5.29 |

| 2013 | 29 098 (2.04)* | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.83 | 1.79 | 3.76 | 6.95 | 10.88 | 12.69 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2003 | 14 873 (1.22) | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 1.23 | 3.34 | 7.10 | 8.70 | 4.78 |

| 2013 | 28 562 (2.00)* | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 1.45 | 3.92 | 8.66 | 11.34 | 9.89 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2003 | 28 098 (2.31) | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 2.74 | 6.59 | 12.09 | 15.26 | 11.51 |

| 2013 | 56 770 (3.97)* | 0.18 | 0.38 | 1.12 | 3.24 | 7.82 | 15.35 | 22.51 | 23.85 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2003 | 37 897 (3.12) | 0.78 | 1.32 | 1.95 | 3.46 | 7.25 | 12.22 | 15.14 | 12.85 |

| 2013 | 50 705 (3.55)* | 0.74 | 1.26 | 1.80 | 3.02 | 5.77 | 10.73 | 17.17 | 21.15 | |

| Renal disease | 2003 | 13 999 (1.15) | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.77 | 1.57 | 2.80 | 4.54 | 5.07 | 3.44 |

| 2013 | 38 748 (2.71)* | 0.18 | 0.44 | 1.06 | 2.44 | 5.19 | 9.64 | 13.79 | 14.13 | |

| Liver disease | 2003 | 43 555 (3.58) | 1.39 | 2.58 | 4.03 | 5.53 | 6.23 | 5.44 | 3.41 | 1.64 |

| 2013 | 71 015 (4.97)* | 0.79 | 2.88 | 5.13 | 7.28 | 8.56 | 8.05 | 5.69 | 4.03 | |

| Dementia | 2003 | 5194 (0.43) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 2.24 | 5.06 | 6.27 |

| 2013 | 18 869 (1.32)* | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 1.27 | 4.89 | 12.77 | 20.54 | |

| Other neurological disorders | 2003 | 124 029 (10.20) | 4.25 | 6.84 | 9.44 | 13.12 | 18.24 | 24.21 | 26.53 | 17.78 |

| 2013 | 217 307 (15.20)* | 6.54 | 10.37 | 13.29 | 16.90 | 21.42 | 29.04 | 33.85 | 31.03 | |

| Digestive disorders | 2003 | 152 161 (12.52) | 6.81 | 8.54 | 11.19 | 14.94 | 21.03 | 29.22 | 32.39 | 25.95 |

| 2013 | 227 327 (15.90)* | 8.41 | 11.15 | 13.40 | 17.09 | 22.01 | 29.06 | 35.24 | 37.48 | |

| Osteoporosis | 2003 | 14 732 (1.21) | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 2.04 | 3.59 | 5.02 | 6.08 | 5.45 |

| 2013 | 17 026 (1.19) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.74 | 2.10 | 5.23 | 7.67 | 9.15 | |

| Arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis) | 2003 | 149 434 (12.29) | 3.87 | 6.34 | 11.05 | 18.01 | 25.54 | 31.95 | 30.18 | 19.63 |

| 2013 | 226 844 (15.87)* | 4.18 | 7.28 | 12.01 | 19.46 | 27.70 | 37.45 | 37.03 | 29.30 | |

| Anxiety, dissociative and somatoform disorders | 2003 | 52 029 (4.28) | 1.27 | 2.48 | 4.17 | 6.34 | 8.48 | 9.99 | 9.49 | 5.91 |

| 2013 | 89 053 (6.23)* | 1.69 | 3.45 | 5.82 | 8.00 | 10.29 | 11.91 | 11.18 | 8.44 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 2003 | 8251 (0.68) | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 0.89 | 0.51 |

| 2013 | 15 439 (1.08)* | 0.51 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.44 | 1.50 | 1.32 | 0.92 | |

| Depression | 2003 | 11 630 (0.96) | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.51 | 1.61 | 1.13 |

| 2013 | 24 712 (1.73)* | 0.86 | 1.30 | 1.89 | 2.00 | 2.24 | 2.52 | 2.59 | 2.25 | |

| Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders | 2003 | 7472 (0.61) | 0.48 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| 2013 | 11 624 (0.81)* | 0.42 | 0.82 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.67 | |

| Cancer | 2003 | 37 438 (3.08) | 1.26 | 2.22 | 3.77 | 4.11 | 4.47 | 5.50 | 5.46 | 2.93 |

| 2013 | 83 065 (5.81)* | 1.36 | 2.97 | 5.68 | 7.22 | 9.19 | 11.54 | 12.57 | 12.16 | |

*P<0.05 compared with prevalence in 2003 using χ2 tests.

As shown in table 3, in general, the prevalence of each common disease increased between the years 2003 and 2013 in both men and women. In men, the prevalence of chronic pulmonary disease and cardiovascular-related diseases, including hypertension, congestive heart failure and peripheral vascular disease, was predominant. In women, the prevalence of osteoporosis, arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis), cancer, and psychosomatic disorders, including depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder, was predominant. Interestingly, the prevalence of dementia in men was slightly higher than in women in 2003; however, in 2013, the condition was much higher in women than in men.

Table 3.

Prevalence of 20 common diseases in Taiwan, by sex, age group and year

| Disease | Year | Prevalence (%) | Prevalence of each disease, by age group (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | 90+ | ||||||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| Hypertension | 2003 | 10.52 | 10.33 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 1.90 | 0.92 | 7.29 | 5.42 | 17.13 | 17.09 | 27.66 | 31.83 | 39.89 | 44.96 | 41.16 | 45.18 | 29.55 | 28.31 |

| 2013 | 19.40 | 17.13 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 3.58 | 1.35 | 12.67 | 6.71 | 25.93 | 20.10 | 40.55 | 38.81 | 51.88 | 58.30 | 58.03 | 65.22 | 54.02 | 58.70 | |

| Diabetes | 2003 | 4.77 | 4.56 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 1.05 | 0.51 | 3.73 | 2.34 | 9.15 | 7.94 | 13.07 | 14.86 | 14.10 | 18.64 | 11.47 | 13.47 | 5.75 | 5.93 |

| 2013 | 9.57 | 8.26 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 1.75 | 0.86 | 6.18 | 2.97 | 13.52 | 9.56 | 21.87 | 20.40 | 24.50 | 27.96 | 22.52 | 27.81 | 17.60 | 18.99 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2003 | 3.71 | 3.63 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 2.12 | 1.51 | 5.48 | 5.25 | 9.58 | 11.16 | 16.27 | 18.28 | 19.34 | 20.51 | 17.10 | 15.14 |

| 2013 | 5.24 | 4.72 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 2.56 | 1.25 | 5.82 | 4.21 | 10.67 | 9.58 | 16.02 | 18.15 | 23.37 | 26.13 | 27.04 | 29.18 | |

| Coronary syndrome | 2003 | 3.21 | 2.67 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 1.51 | 0.89 | 4.47 | 3.55 | 8.81 | 8.70 | 15.53 | 14.07 | 16.88 | 15.30 | 11.76 | 10.86 |

| 2013 | 5.00 | 3.52 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 2.14 | 0.78 | 5.49 | 2.99 | 11.24 | 7.71 | 16.41 | 14.36 | 20.94 | 18.55 | 20.42 | 17.65 | |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 2003 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 1.39 | 1.54 | 2.90 | 2.88 | 5.40 | 5.06 | 6.85 | 6.51 | 6.57 | 4.53 |

| 2013 | 2.10 | 1.98 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 1.83 | 1.77 | 3.94 | 3.60 | 7.08 | 6.84 | 11.69 | 10.11 | 12.81 | 12.61 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2003 | 1.23 | 1.22 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 1.20 | 1.25 | 3.01 | 3.62 | 7.01 | 7.19 | 8.97 | 8.46 | 5.61 | 4.28 |

| 2013 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 1.60 | 1.32 | 3.83 | 4.00 | 8.06 | 9.16 | 11.76 | 10.95 | 11.25 | 8.82 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2003 | 2.61 | 2.04 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 1.07 | 0.67 | 3.18 | 2.36 | 7.05 | 6.19 | 13.01 | 11.11 | 16.29 | 14.31 | 14.09 | 9.96 |

| 2013 | 4.54 | 3.46 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 1.47 | 0.80 | 4.05 | 2.50 | 9.15 | 6.61 | 16.65 | 14.28 | 24.45 | 20.67 | 24.81 | 23.09 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2003 | 3.51 | 2.76 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 1.24 | 1.39 | 1.99 | 1.93 | 3.50 | 3.41 | 8.02 | 6.59 | 15.19 | 9.08 | 19.80 | 10.86 | 17.51 | 10.04 |

| 2013 | 4.00 | 3.14 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 1.16 | 1.34 | 1.75 | 1.85 | 3.09 | 2.96 | 6.52 | 5.10 | 13.26 | 8.62 | 21.96 | 12.60 | 26.98 | 16.58 | |

| Renal disease | 2003 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.68 | 1.48 | 3.02 | 2.62 | 4.90 | 4.16 | 6.09 | 4.14 | 4.51 | 2.80 |

| 2013 | 3.26 | 2.22 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 1.42 | 0.72 | 3.04 | 1.89 | 6.25 | 4.23 | 11.26 | 8.29 | 15.84 | 11.85 | 16.96 | 11.91 | |

| Liver disease | 2003 | 4.61 | 2.66 | 2.12 | 0.76 | 3.95 | 1.36 | 5.64 | 2.56 | 6.38 | 4.78 | 6.70 | 5.83 | 5.59 | 5.28 | 3.90 | 2.96 | 2.19 | 1.32 |

| 2013 | 6.20 | 3.86 | 1.12 | 0.49 | 4.30 | 1.66 | 7.35 | 3.12 | 8.92 | 5.76 | 9.21 | 7.97 | 8.49 | 7.68 | 6.13 | 5.28 | 4.66 | 3.53 | |

| Dementia | 2003 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 2.14 | 2.35 | 4.82 | 5.28 | 4.24 | 7.49 |

| 2013 | 1.31 | 1.33 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 1.31 | 1.23 | 4.52 | 5.20 | 11.70 | 13.79 | 18.81 | 21.89 | |

| Other neurological disorders | 2003 | 8.00 | 12.17 | 3.29 | 5.08 | 5.24 | 8.27 | 6.90 | 11.76 | 9.31 | 16.48 | 14.62 | 21.32 | 21.26 | 27.32 | 23.99 | 28.86 | 17.10 | 18.19 |

| 2013 | 12.02 | 18.05 | 4.74 | 8.19 | 7.79 | 12.59 | 10.02 | 16.25 | 12.66 | 20.81 | 16.84 | 25.58 | 25.34 | 32.12 | 32.25 | 35.37 | 30.73 | 31.26 | |

| Digestive disorders | 2003 | 11.62 | 13.32 | 4.92 | 8.46 | 7.63 | 9.35 | 10.53 | 11.79 | 13.78 | 15.96 | 19.84 | 22.04 | 29.87 | 28.54 | 34.65 | 30.32 | 28.04 | 24.69 |

| 2013 | 14.01 | 17.60 | 5.65 | 10.93 | 8.59 | 13.34 | 11.63 | 15.00 | 15.14 | 18.91 | 20.14 | 23.69 | 28.32 | 29.67 | 37.55 | 33.04 | 41.88 | 34.03 | |

| Osteoporosis | 2003 | 0.45 | 1.89 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.70 | 0.41 | 3.48 | 0.91 | 5.87 | 2.07 | 8.14 | 2.75 | 9.14 | 4.10 | 6.26 |

| 2013 | 0.58 | 1.74 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 1.02 | 0.76 | 3.31 | 1.98 | 7.93 | 3.72 | 11.43 | 5.25 | 12.21 | |

| Arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis) | 2003 | 12.26 | 12.32 | 4.81 | 3.05 | 7.46 | 5.35 | 11.49 | 10.65 | 16.09 | 19.70 | 22.43 | 28.20 | 30.16 | 33.85 | 29.71 | 30.61 | 22.85 | 17.70 |

| 2013 | 15.32 | 16.36 | 4.89 | 3.53 | 8.75 | 6.03 | 12.75 | 11.34 | 18.01 | 20.80 | 24.02 | 31.04 | 32.67 | 41.43 | 35.62 | 38.37 | 30.49 | 28.36 | |

| Anxiety, dissociative and somatoform disorders | 2003 | 3.36 | 5.10 | 1.11 | 1.42 | 2.05 | 2.86 | 3.26 | 5.01 | 4.47 | 7.99 | 6.27 | 10.36 | 8.18 | 11.91 | 8.46 | 10.44 | 6.43 | 5.60 |

| 2013 | 4.90 | 7.42 | 1.50 | 1.86 | 2.95 | 3.87 | 4.76 | 6.78 | 5.99 | 9.87 | 7.55 | 12.78 | 9.09 | 14.26 | 9.34 | 12.94 | 7.93 | 8.84 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 2003 | 0.55 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.63 | 1.02 | 0.72 | 1.03 | 0.87 | 1.20 | 0.76 | 1.02 | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| 2013 | 0.84 | 1.29 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 1.52 | 0.97 | 1.62 | 1.04 | 1.79 | 1.10 | 1.84 | 1.09 | 1.54 | 0.99 | 0.86 | |

| Depression | 2003 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 0.86 | 1.39 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 1.32 | 1.71 | 1.44 | 1.77 | 0.82 | 1.32 |

| 2013 | 1.42 | 2.00 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 1.11 | 1.47 | 1.56 | 2.19 | 1.56 | 2.42 | 1.70 | 2.73 | 1.96 | 2.98 | 2.23 | 2.93 | 2.20 | 2.29 | |

| Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders | 2003 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| 2013 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.74 | |

| Cancer | 2003 | 2.21 | 3.85 | 0.90 | 1.58 | 1.22 | 3.11 | 1.80 | 5.56 | 2.80 | 5.26 | 4.26 | 4.66 | 6.22 | 4.73 | 6.82 | 4.21 | 4.38 | 2.06 |

| 2013 | 5.06 | 6.49 | 1.02 | 1.67 | 1.82 | 3.95 | 3.41 | 7.73 | 5.76 | 8.57 | 9.09 | 9.29 | 13.37 | 10.02 | 15.81 | 9.49 | 16.21 | 8.99 | |

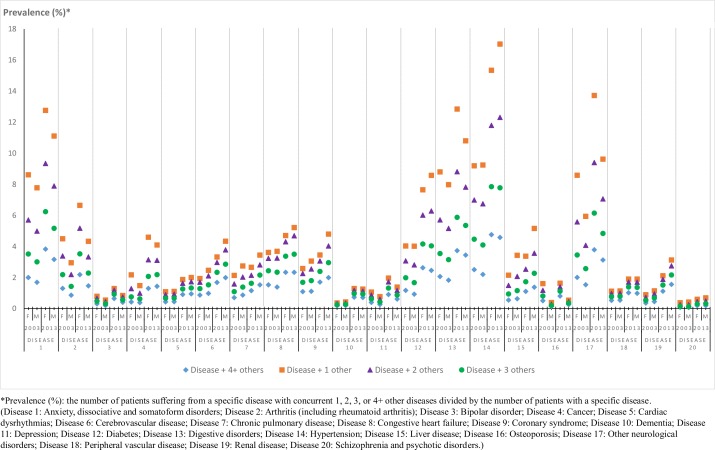

In figure 2, we depicted sex differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity for individuals suffering from each common disease in 2003 and 2013. Generally, compared with 2003, multimorbidity was more frequently observed in 2013 in both sexes for all common diseases. Except for bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, which were the least likely to occur with other diseases, the other studied diseases might be comorbid to some extent. In 2003, patients with anxiety, dissociative and somatoform disorders, digestive disorders, and hypertension were most likely to suffer from other diseases concurrently, but the differences by sex were minor. In 2013, patients with these diseases were most likely to have other diseases at the same time; however, the sex differences were more noticeable. Specifically, a higher proportion of women suffering from anxiety, dissociative and somatoform disorders, and digestive disorders have greater odds of having other concurrent diseases. A profound sex difference in multimorbidity could also be observed in patients with other diseases, including arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis), osteoporosis, other neurological disorders and liver disease, where women with the first three of these conditions had a higher prevalence of other concurrent diseases.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of multimorbidity in Taiwan within common diseases, by sex and year. F, female; M, male.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this population-based study is the largest and most comprehensive epidemiological study to provide age- and gender-specific information on multimorbidity in the Taiwanese population. Previous studies of this topic have been limited to Western countries, such as Canada6 or Australia.13 Nevertheless, the aetiology of multimorbidity may have geographical discrepancies. Our study also fills the knowledge gap of existing studies conducted in Asian countries17 18 by providing nationwide estimates of multimorbidity across different age groups and illuminating the 10-year changes in the multimorbidity burden, which was not available from existing studies. This information is therefore fundamental for constructing national policies to combat the burden of multimorbidity, particularly in Asian countries. Our study also provides indepth analyses of each selected disease and its concomitant comorbidities. This study could thus serve as a valuable reference for formulating strategic disease management plans.

We found that the prevalence of multimorbidity increased in the 10-year follow-up period. This increase is reasonable considering the ageing population28 and is consistent with a previous study conducted in Ontario.6 The prevalence of multimorbidity among residents of Ontario rose from 17.4% in 2003 to 24.3% in 2009, a 40% increase. In our study, the prevalence of multimorbidity rose from 20.07% in 2013 to 30.44% in 2009, a 51.6% increase. The different magnitudes of the increase could have resulted from the various lists of diseases selected to assess multimorbidity; the Ontario study included 16 common chronic conditions,6 while our study included 20 common chronic conditions. However, the rate of demographic ageing in the two different populations may better explain the discrepancies. The population is ageing rapidly in Taiwan. At the end of 2010, 11% of Taiwan’s population was 65 years or older. The ratio of elderly people reached 14% (the threshold for an ‘aged’ society) in 2017, and the estimated ratio is expected to increase to 20% (the threshold for a ‘superaged’ society) in Taiwan by 2025.29

An understanding of multimorbidity, particularly in the elderly, is therefore very important for almost every country. In our study, we found that the prevalences of multimorbidity (2+ diseases) in people aged 60–69, 70–79 and 80–89 were 56.84%, 74.64% and 82.64%, respectively, in 2013. The prevalences of multimorbidity (3+ diseases) in people aged 60–69, 70–79 and 80–89 were 37.49%, 57.04% and 68.10%, respectively, in 2013. Facing such tremendous and complex medical demands, it is necessary to reform the current ‘single-disease or specialty’ paradigm into a ‘integrated and comprehensive medical care’ model.30 We also found that the combination and intensity of multimorbidity differed in older men and women. This finding may further indicate different medical needs for older men and women, and gender-specific care plans for older people may be warranted. Our estimates can serve as a reference for countries facing a similar rapid speed of population ageing to better allocate medical and social welfare resources, including for Taiwan, our neighbour country Japan31 or other European countries.32

In addition to older people, the prevalence of multimorbidity among the younger population warrants special attention. As most studies of multimorbidity have focused on older adults,33 34 evidence regarding this issue in young adults is very limited. In our study, the prevalences of multimorbidity (2+ diseases) in people aged 30–39, 40–49 and 50–89 were 11.18%, 21.76% and 37.75%, respectively, in 2013. This indicates the need for early intervention in those who already suffer from multimorbidity in middle age, as the intensity of multimorbidity gradually increases, as shown in our study. Lifestyle factors in middle age, such as smoking, drinking, exercise and diet, have been reported to be associated with multimorbidity.35

Most importantly, our study contributes to a better understanding of the indepth details of multimorbidity. In addition to revealing very distinct predominant diseases in men and women, we also revealed the burden of multimorbidity in each common chronic condition. From a clinical perspective, our findings can help further stratify patients within specific disease groups. For example, patient care for those with diabetes mellitus and one other comorbid condition would be very different from patients with diabetes mellitus and four other comorbid conditions. From a policy perspective, our findings can help allocate medical resources more efficiently. Our previous studies have also supported this stratification strategy (identifying high-risk groups), and we found that an increase in diabetic complications was positively associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation and increased healthcare costs.36 37

Here, we have provided epidemiological information of age-specific and gender-specific multimorbidity; however, there are some limitations due to the nature of the claims data. First, we identified the disease based on the diagnoses recorded at the outpatient or inpatient visits. However, only up to three or up to five diagnoses were allowed to be recorded for each outpatient or inpatient visit, respectively; therefore, the prevalence of multimorbidity may be underestimated. Second, as we used the NHIRD, the estimations regarding multimorbidity were from the perspective of the national insurance system. Patients who pay out of pocket for their healthcare are not recorded in the NHIRD. Third, as there is no consensus on the number of diseases used to identify multimorbidity, epidemiological comparisons with different countries are difficult. For example, a systematic review conducted by Pati et al 17 revealed that among 13 studies, the number of health conditions analysed per study varied from 7 to 22, with the prevalence of multimorbidity varying from 4.5% to 83%.

In summary, our study is the first population-based study conducted in Taiwan that provides age-specific and gender-specific information on multimorbidity. The burden of multimorbidity is increasing and becoming more complex in Taiwan. Providing for the needs of individuals with multimorbidity requires collaborative work across healthcare providers and may need to take into account age and gender disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) and the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) for making the databases used in this study available. However, the content of this article does not represent any official position of the NHIA or NHRI. The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: R-HH, F-YH, L-JC and WWYH contributed to the study concept and design. F-YH, R-HH and P-TH acquired and analysed the data. F-YH and L-JC interpreted the data. R-HH, F-YH, L-JC, P-TH and WWYH drafted the manuscript. F-YH and WWYH revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: WWYH received research assistantships from a research project (MOST107- 2221-E-019-037-MY3) sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology Taiwan. F-YH received research assistantships from a research project (MOST 104-2410-H-002-225-MY3) sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology Taiwan.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The identification numbers for all of the entries in the NHIRD were encrypted to protect the privacy of the individual patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee No 201403069W).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data for this study were provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Taiwan, following ethical approval, and may be available to other researchers who meet data access requirements.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, et al. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:134–41. 10.1370/afm.1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schram MT, Frijters D, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Setting and registry characteristics affect the prevalence and nature of multimorbidity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1104–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor AW, Price K, Gill TK, et al. Multimorbidity - not just an older person’s issue. Results from an Australian biomedical study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:718 10.1186/1471-2458-10-718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health 2015;15:415 10.1186/s12889-015-1733-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Oostrom SH, Picavet HS, de Bruin SR, et al. Multimorbidity of chronic diseases and health care utilization in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:61 10.1186/1471-2296-15-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Oostrom SH, Picavet HS, van Gelder BM, et al. Multimorbidity and comorbidity in the Dutch population - data from general practices. BMC Public Health 2012;12:715 10.1186/1471-2458-12-715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Araujo MEA, Silva MT, Galvao TF, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Amazon Region of Brazil and associated determinants: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023398 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brett T, Arnold-Reed DE, Popescu A, et al. Multimorbidity in patients attending 2 Australian primary care practices. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:535–42. 10.1370/afm.1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust 2008;189:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Excoffier S, Herzig L, N’Goran AA, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in general practice: a cross-sectional study within the Swiss Sentinel Surveillance System (Sentinella). BMJ Open 2018;8:e019616 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harrison C, Henderson J, Miller G, et al. The prevalence of complex multimorbidity in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016;40:239–44. 10.1111/1753-6405.12509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harrison C, Henderson J, Miller G, et al. The prevalence of diagnosed chronic conditions and multimorbidity in Australia: A method for estimating population prevalence from general practice patient encounter data. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172935 10.1371/journal.pone.0172935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e245–e251. 10.3399/bjgp18X695465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stanley J, Semper K, Millar E, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in New Zealand: a cross-sectional study using national-level hospital and pharmaceutical data. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021689 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pati S, Swain S, Hussain MA, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of multimorbidity in South Asia: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007235 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu X, Huang J, Lv Y, et al. Status of prevalence study on multimorbidity of chronic disease in China: systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:1–10. 10.1111/ggi.12340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ge L, Yap CW, Heng BH. Sex differences in associations between multimorbidity and physical function domains among community-dwelling adults in Singapore. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197443 10.1371/journal.pone.0197443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mini GK, Thankappan KR. Pattern, correlates and implications of non-communicable disease multimorbidity among older adults in selected Indian states: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013529 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pati S, Hussain MA, Swain S, et al. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Assess Multimorbidity in Primary Care: An Indian Experience. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–9. 10.1155/2016/6582487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsiao FY, Yang CL, Huang YT, et al. Using Taiwan’s national health insurance research databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. J Food Drug Anal 2007;15:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Health Research Institute, Taiwan. National Health Insurance Research Database, Taiwan. https://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/Data_Subsets.html (accessed 22 Aug 2018).

- 24. Chen CY, Wu VC, Lin CJ, et al. Improvement in Mortality and End-Stage Renal Disease in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes After Acute Kidney Injury Who Are Prescribed Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1760–74. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wen YC, Chen LK, Hsiao FY. Predicting mortality and hospitalization of older adults by the multimorbidity frailty index. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187825 10.1371/journal.pone.0187825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dai YX, Wang SC, Chou YJ, et al. Smoking, but not alcohol, is associated with risk of psoriasis in a Taiwanese population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:727–34. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lenzi J, Avaldi VM, Rucci P, et al. Burden of multimorbidity in relation to age, gender and immigrant status: a cross-sectional study based on administrative data. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012812 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wh L, Lee WJ, Chen LK, et al. Comparisons of annual health care utilization, drug consumption, and medical expenditure between the elderly and general population in Taiwan. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2016;7:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Development Council. Population Projections for R.O.C. (Taiwan):2014-2060. https://www.ndc.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=84223C65B6F94D72 (accessed 21 Nov 2018).

- 30. Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K, et al. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: Perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:673–87. 10.1111/ggi.12450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arai H, Ouchi Y, Yokode M, et al. Toward the realization of a better aged society: messages from gerontology and geriatrics. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:16–22. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Perales J, Martin S, Ayuso-Mateos JL, et al. Factors associated with active aging in Finland, Poland, and Spain. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26:1363–75. 10.1017/S1041610214000520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract 2008;14(Suppl 1):28–32. 10.1080/13814780802436093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:367–75. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00306-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fortin M, Haggerty J, Almirall J, et al. Lifestyle factors and multimorbidity: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:686 10.1186/1471-2458-14-686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen HL, Hsiao FY. Risk of hospitalization and healthcare cost associated with Diabetes Complication Severity Index in Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. J Diabetes Complications 2014;28:612–6. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen HL, Hsu WW, Hsiao FY. Changes in prevalence of diabetic complications and associated healthcare costs during a 10-year follow-up period among a nationwide diabetic cohort. J Diabetes Complications 2015;29:523–8. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028333supp001.pdf (413.6KB, pdf)