Abstract

Introduction

The aim of the present study is to investigate the effectiveness of pulsed low-frequency magnetic field (PLFMF) on the management of chronic low back pain (CLBP).

Methods and analysis

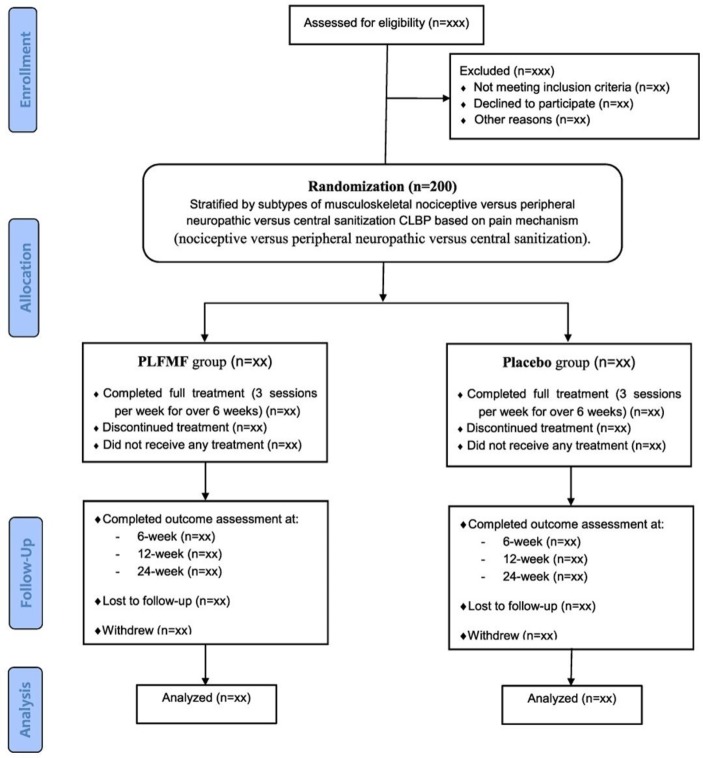

A randomised double-blinded controlled clinical trial will be conducted, involving 200 patients with CLBP. Participants will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive either active PLFMF (experimental arm) or sham treatment (control arm) using a permuted-block design which will be stratified according to three subtypes of musculoskeletal CLBP (nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic or central sanitisation). The intervention consists of three sessions/week for 6 weeks. The primary outcome is the percentage change in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain at week 24 after treatment completion with respect to the baseline. Secondary outcomes include percentage NRS pain during treatment and early after treatment completion, short form 36 quality of life, Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire; Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21, Patient Specific Functional Scale, Global perceived effect of condition change, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. Measures will be taken at baseline, 3 and 6 weeks during the intervention and 6, 12 and 24 weeks after completing the intervention. Adverse events between arms will be evaluated. Data will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is funded by Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IAU). It has been approved by the institutional review board of IAU (IRB‐ 2017‐03–129). The study will be conducted at King Fahd Hospital of the University and will be monitored by the Hospital monitoring office for research and research ethics. The trial is scheduled to begin in September 2018. Results obtained will be presented in international conferences and will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618000921280, prospectively.

Keywords: low back pain, pulsed low-frequency magnetic field, randomised double-blinded controlled clinical trial, efficacy, safety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study is a well-designed trial to investigate the long-term efficacy and safety of pulsed low-frequency magnetic field (PLFMF) on the management of musculoskeletal chronic low back pain (LBP).

Subgroup analysis investigating the efficacy of PLFMF on various subtypes of pain based on pain mechanism will be performed. This may help to explain controversial results reported by previous clinical trials.

Outcome measures include various aspects of LBP problems (pain intensity as well as disabilities, functional limitations, sleep quality and quality of life).

All outcome measures used in the present trial are self-report which may potentiate pain and other measured outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is a pain or discomfort localised in the lumbosacral region, with or without leg pain (sciatica) that persists for more than 3 months.1 Eight out of every ten adults will experience low back pain (LBP) at least once in their life with more than 60% of such cases have a recurrent LBP.2 Evidence suggests that LBP has a lifetime prevalence of 40%, and a mean point prevalence of 20%.3 The causes of LBP are many, they can range from simple spasm or mechanical causes to more serious causes such as herniated disc and different types of cancer.4 Symptoms of LBP may vary from one patient to another. In many patients, the symptoms may go beyond pain to lead to severe consequences such as sleep disturbances, psychological and social problems which may affect the quality of life.5 CLBP accounts for about 15% of all cases of LBP; however, it has been reported to be the world-leading source of disability.6 In addition, CLBP is often associated with the socioeconomic burden and psychological distress.7 There is no published evidence of LBP cost in Saudi Arabia, the treatment cost for LBP in the USA is estimated to be more than $90 billion per year8 and $17 billion per year in the UK.9

LBP can be classified based on several criteria. It has been classified into acute and chronic based on how long the pain has persisted. It can also be classified into inflammatory and neuropathic based on the underlying mechanism.10 The main issue is how to differentiate the various subtypes clinically. In many occasions, differentiating the various phenotypes clinically is difficult. Smart et al 11–13 proposed a mechanism-based classification to differentiate between different types of musculoskeletal LBP (central sensitisation, peripheral neuropathic and nociceptive).

Most of the mechanical LBP respond to rest and various physical modalities. Different conservative and surgical interventions have been used to manage CLBP; however, optimal therapy is still debatable.14 Many physical therapy interventions were tried in the management of CLBP such as soft tissue mobilisation and neurodynamic techniques,15 16 massage therapy,17 ultrasound, laser therapy, and shock wave therapy,18 exercises,19 Pilates practice,20 and acupuncture.21 While some of the rehabilitation interventions were effective in the short term, none of such interventions produce long-term effectiveness in the management of CLBP.2

Many pharmacological interventions have been used to manage CLBP. For example, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs and trammel were mild to moderately effective in reducing pain without much effects on function.17 Similarly, opioids, benzodiazepines and duloxetine effects on reducing CLBP were small without inducing any improvement in function.22 Other drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin were used; however, their efficacy was not established.23 Since CLBP persist for long term, pharmacological interventions are not a suitable solution due to many reasons. Such reasons include toxicity due to long-term use, side and adverse effects in addition to problems with tolerance and addiction.24 Surgical procedures have been used in some cases of CLBP with a mixed outcome25; however, many patients are reluctant to go through surgery. Add to that the high cost of the surgery to the healthcare system. Furthermore, the number of what is called ‘failed back surgery syndrome’ is in the rise.26

Since the conservative approaches currently used to manage CLBP do not seem to be effective on the long term, new approaches are needed to be developed. The new approaches should be safe, non-invasive and cost-effective.

Several lines of evidence indicate that pulsed low-frequency magnetic field (PLFMF) may be an attractive option for the management of CLBP. Magnetic field blocked the sensory neuron action potential in cultured neurons27; however, it enhanced neuronal growth in the presence of growth factor.28 In rats, magnetic field suppressed the formation of oedema.29 Weintraub et al 30 showed that magnetic field has a pronounced anti-nociceptive effect. Robertson et al 31 showed that PLFMF affected pain and thermal signals in normal volunteers. Selvam et al 32 reported that PLFMF restored the calcium ATPase activity of the plasma membrane and produced anti-inflammatory effects. PLFMF also inhibited pain processing in a dose-dependent manner.33 Clinically, PLFMF has been used for the treatment of different types of pain such as plantar fasciitis,34 lumber radicular pain,35 postoperative pain,36 peripheral neuropathy30 and osteoarthritis.37 Recently, we concluded a study which showed that PLFMF was effective in reducing pain, improving sleep and quality of life in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome.38

In the case of CLBP, few studies were done and produced conflicting results. While Krammer et al,14 Oke and Umebese,39 and Harden et al 40 reported that PLFMF was not superior to sham treatment in patients with CLBP, other studies reported that PLFMF significantly reduced pain intensity in patients with CLBP.41–43 Most of the studies which tested the effects of PLFMF on CLBP suffered from methodological problems and flaws. Such problems included failure to perform intention to treat as well as lack of proper blindness of patients and researchers. All these studies failed to classify the CLBP into different subgroups since CLBP is heterogeneous. Two of the studies reporting positive findings failed to compare PLFMF with other therapeutic modality.42 43 All the mentioned studies used small number sample sizes (16–40 patients).44 Some of these studies did not do any follow-up after the conclusion of the interventions or did a follow-up for a short period.45 Finally, the six studies used different machines producing different magnetic field intensity and frequency and different treatment protocols. Similarly, various studies reported controversial results regarding the effects of PLFMF on the level of disability and quality of life in patients with CLBP. Some studies reported that PLFMF improved the level of disability and/or quality of life41 42 46 while other studies reported no effects for PLFMF on disability and/or quality of life.14 43 47 Two systematic reviews investigated the effects of PLFMF on CLBP. Andrade et al 45 concluded that PLFMF treatment is superior to placebo treatment. However, Hug and Roosli48 concluded that available evidence is not sufficient to recommend the use of PLFMF clinically. Both reviews recommended better controlled randomised studies are needed to clarify the effects of PLFMF on CLBP.

PLFMF is known to be safe, non-invasive, low cost, easy to administer and has no known side effects in the management of patients with CLBP.48 Improving the condition of patients with CLBP will spare the patient going through several rounds of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment as well as invasive procedures like surgery with the ultimate goal to improve the patients’ quality of life.

Objectives

The primary objective of this randomised controlled trial is to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of PLFMF on the management of CLBP and on increasing the percentage change in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain at week-24 with respect to baseline score. The percentage reduction in NRS pain at week 24 will also be evaluated according to various musculoskeletal CLBP subtypes based on pain mechanism (nociceptive vs peripheral neuropathic vs central sanitisation).11–13

The secondary objectives are to evaluate the effects of PLFMF on (1) pain intensity during treatment and early after treatment completion, (2) level of disability, (3) functional levels, (4) sleep quality, (5) quality of life and (6) fatigue in patients with CLBP. The study will also investigate the long-term side effects of PLFMF.

This study will also include subgroups exploratory objectives to clarify the role of PLFMF in the management of patients diagnosed with different subtypes of musculoskeletal CLBP. To the best of our knowledge, this trial is the first randomised clinical trial to explore simultaneously the role of PLFMF in the management of patients with peripheral neuropathic, nociceptive and central sensitisation musculoskeletal LBP together.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is a two-arm randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The study will be coordinated at the King Fahd Hospital of the University. All participants will be recruited from the hospital (patients referred to the department, additionally flyers will be distributed inviting people to participate). This study is funded through the Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IAU; grant number 2017–308-CAMS). Ethical approval has been obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of the IAU (IRB‐ 2017‐03–129). This study is prospectively registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Registration Number ACTRN12618000921280). Table 1 shows Trial Registration Data Set. This trial protocol has been prepared according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials checklist statement (see online supplementary appendix 1).49

Table 1.

Trial Registration Data Set

| Data category | Information |

| Primary registry and trial identifying number | Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry ACTRN 12618000921280) |

| Date of registration in primary registry | 31/05/2018 |

| Secondary identifying numbers | IAU-2017–308-CAMS |

| Source(s) of monetary or material support | King Fahd Hospital of the University |

| Primary sponsor | Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University |

| Secondary sponsor(s) | None |

| Contact for public queries | Fuad A. Abdulla, PhD, PT +966 13 3331308 faabdullah@iau.edu.sa |

| Contact for scientific queries | Fuad A. Abdulla, PhD, PT +966 13 3331308 faabdullah@iau.edu.sa |

| Public title | Effects of Pulsed Low Frequency Magnetic Field Therapy on Pain Intensity in Patients with Musculoskeletal Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Trial |

| Scientific title | Effects of Pulsed Low Frequency Magnetic Field Therapy on Pain Intensity in Patients with Musculoskeletal Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Trial |

| Countries of recruitment | Saudi Arabia |

| Health condition(s) or problem(s) studied | Chronic Low Back Pain |

| Intervention(s) | Active comparator: PLFMF, an average of 14 μT for 20 min) and the conventional physical therapy programme (three times per week for 6 weeks) Placebo comparator: sham PLFMF (the machine will not be activated, ie, no magnetic field will be generated, for 20 min) and the conventional physical therapy programme (three times per week for 6 weeks) The conventional physical therapy programme consists of: · Hot packs for 20 min · Back, hamstring and calf muscles stretching (performed from the long sitting position) · Lumbar erector spinae muscles self-stretching · Back muscles strengthening (back extension and bridging) · Abdominal muscles strengthening (posterior pelvic tilt and sit-ups) Participants will be asked to hold the above positions for 5 s. Each exercise will be done five times per session with 1 min rest between any two repetitions |

| Key inclusion and exclusion criteria | Ages eligible for study: 18–60 years Sexes eligible for study: both Accepts healthy volunteers: no Inclusion criteria: · Clinical evidence of musculoskeletal chronic low back pain including subtype classification (nociceptive vs peripheral neuropathic vs central sanitization) · Age 18–60 years old · Primary complaint of pain (at least a score of 5 out of 10 on a 0–10 NRS) in the area between the 12th rib and buttock crease, with or without leg pain for 3 months or more Exclusion criteria: · Pregnant or lactating · Significant spinal pathology (eg, spinal fracture, cauda equina syndrome, spinal infective or inflammatory diseases, metastatic) · Spinal surgery within the preceding 6 months · Recent organ transplants · Heart pacemaker · Cardiac arrhythmia, tachycardia conditions or large aneurysm · Heavy psychosis · Epileptic episodes |

| Study type | Interventional Allocation: randomised Allocation concealment: sealed opaque envelopes Sequence generation: permuted-block randomization Intervention model: parallel assignment Masking: double-blind (subject, caregiver, investigator, outcomes assessor) Primary purpose: treatment |

| Date of first enrolment | September 2018 |

| Target sample size | 200 |

| Recruitment status | Will begin Recruiting in July |

| Primary outcome(s) | The percentage change in pain intensity by calculating the percentage change in NRS of pain. The percentage change in pain will be calculated at each post-baseline assessment as: All patients will be evaluated at baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. To assess for effects persistence, participants will be also evaluated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions |

| Key secondary outcomes | a. Quality of life assessed using Short Form 36 quality of life questionnaire. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions b. Disability assessed by the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions c. Depression, anxiety and stress assessed by Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 questionnaire. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions d. Function measurement assessed by the Patient Specific Functional Scale. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions e. Change in condition assessed by Global perceived effect of condition change. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions f. Quality of sleep assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions g. Fatigue assessed by Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. Time points: baseline, end of the third and the sixth week from the beginning of the intervention. 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the end of the intervention sessions |

NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PLFMF, pulsed low frequency magnetic field.

bmjopen-2018-024650supp001.pdf (149.7KB, pdf)

Sample size and power calculation

Sample size calculation was based on two sample t-tests. We used R function power.t.test via R V.3.4.1 (https://cran.r-project.org). A total sample size of 200 (100 in each arm) will achieve 90% power to detect a mean difference of percentage reduction in NRS pain of 10% between the two treated arms at week 24. The mean percentage reduction in NRS pain is assumed to be 15% in the control arm (patient treated with SHAM programme) and 25% in patients who receive PLFMF therapy. A 0.2 SD is considered along with a two-sided significance level (alpha) of 5% using a two-sample equal-variance t-test. The sample size allows for 15% of patients lost to follow-up at week 24. A 10% absolute reduction in NRS pain at week 24 will translate into an expected effect size of 0.5. This means the NRS score of the average person in the active PLFMF arm is 0.5 the SD above the average person who have had sham treatment, and hence exceed the scores of 69% of the control group.

The 38-item clinical criteria checklist developed by Smart et al 11–13 will be used to classify patients into different phenotypes of musculoskeletal CLBP. This method of discriminative validity was established.11–13 All patients will be analysed collectively. Subgroup analysis will be performed to assess the effect of PLFMF on subtypes of pain.

Statistical analysis

All randomised patients will be analysed on the intention-to-treat basis. Safety analyses will be performed for all patients who received at least one treatment session. Data will be coded and entered into SPSS (version 23; IBM Corp., USA) programme for analysis. Baseline characteristics will be presented by treatment group. Binary and categorical variables will be summarised by frequencies and percentages. Percentages will be calculated according to the number of patients for whom data are available. Where values are missing, the denominator, which will be less than the number of patients assigned to the treatment group, will be reported either in the body or a footnote of the summary table. Continuous variables will be summarised by mean and SD as well as by quartiles. Before summarising continuous outcomes, a test of normality will be performed. If the outcome is normally distributed, it will be summarised by mean (SD) in each arm and the difference between arms will be tested using t-test. However, if no evidence of normality, data will be summarised using the median (IQR). In such case, the Wilcoxon rank sum test will be used to test the difference between arms.

Treatment effect for the primary and continuous secondary outcomes will be assessed through analysis of covariance adjusted for the baseline measurement score. Overall treatment effect over time on all continuous outcomes, repeatedly collected over the course of the study, will be estimated using mixed linear models to take into account the correlation within each individual. The mixed linear model will include random intercept adjusted with the baseline score, time as categorical and the interaction between treatment and time. P values will not be adjusted for multiplicity. However, the outcomes are clearly categorised by degree of importance (primary, main secondary and other secondary) and a limited number of subgroup analyses are pre-specified.

Categorical binary efficacy measures will be primarily analysed using logistic regression. All tests will be two-sided with p values less than 0.05 will be considered significant.

Eligibility criteria

Subjects will be recruited from King Fahd Hospital of the University. Subjects will be included in the study if they fulfil the following criteria:

Clinical evidence of musculoskeletal CLBP including subtype classification (nociceptive vs peripheral neuropathic vs central sanitisation);

Age 18–60 years old;

Primary complaint of pain (at least a score of 5 out of 10 on a 0–10 NRS) in the area between the 12th rib and buttock crease, with or without leg pain for 3 months or more;

Patient will be excluded if they have any of the following criteria:

Pregnant or lactating

Significant spinal pathology (eg, spinal fracture, cauda equina syndrome, spinal infective or inflammatory diseases, metastatic);

Spinal surgery within the preceding 6 months;

Recent organ transplants;

Heart pacemaker;

Cardiac arrhythmia, tachycardia conditions or large aneurysm;

Heavy psychosis;

Epileptic episodes.

Exit criteria

Participants will be withdrawn from the study if:

Become pregnant;

Back pain intensify during the trial to a point which needs emergency medical intervention;

Decided to leave the study voluntarily;

Added new medications (was not taken before) which may affect the patients LBP condition.

Lack of compliance.

Patients will be instructed to continue any medication they regularly take before the trial; however, they will be instructed not to add any new medications that may affect their back pain during the trial period. All prescription and over the counter medications taken by the participants will be recorded.

Randomisation

Eligible participants will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive either active PLFMF treatment (experimental arm) or sham treatment (control arm). Randomisation list will be centrally generated, in a stratified fashion, using a random permuted-block design of size four and six. The stratification factor will be subtypes of musculoskeletal CLBP based on pain mechanism (nociceptive vs peripheral neuropathic vs central sanitisation). A researcher who is not part of the study screening, evaluation or treatment will allocate the participants in one of the groups using sealed dense, tamperproof and numbered envelopes, prior to recruitment.

Tool

The BEMER 3000 (BEMER Int. AG) will be pre-programmed to deliver PLFMF (an average of 14 µT) a pulse frequency of 30 Hz and a pulse duration of 30 ms. The signal comprises a series of half-wave-shaped sinusoidal intensity variations. The signal which starts with low values slowly increases and then decreases but it does not go back to the initial value (ie, stay above zero). The intensity will gradually get denser with the repetition of the sequence leading to an increase in the ups and downs with repetition. Every second this procedure will be repeated 33.3 times with a reversal of polarity every 2 min.50

Blinding

The trial product will be provided in a blinded manner. All the magnetic coils are covered by a cloth. When switched on, the device does not produce any sound or heat to keep patients blinded. Furthermore, to maintain blinding of the investigator (and designated staff), an identical mattress (size) and same colour cloth will be used for all patients independent of treatment group assignment. Patients and all healthcare providers (therapists and physicians) who care for the participants during the study will be strictly blinded to randomised interventions. Only the treating therapist will know what type of treatment the participant will be given. The assessor and the participants will not have access to such information. The blinding codes will be kept at the monitoring office of research and research ethics till the end of the trial unless an emergency developed which requires unblinding. The treating therapist will be asked not to mention or talk about the treatment groups to others. On the completion of the study, each participant will be interviewed to be asked about the group which they think they were at.

Setting

The trial will be conducted at the department of physical therapy of King Fahd Hospital of the University. King Fahd Hospital of the University is a 800-bed teaching hospital located in the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. All researchers are clinicians at the departments of physical therapy and orthopaedics. The trial is scheduled to begin in September 2018.

Procedure

All screening, interventions and evaluation will be done by qualified musculoskeletal physical therapists who have 5 or more years of clinical experience. Potential participants will be asked to participate in the study, if agreed they will be screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria then they will be asked to sign a consent form (see online supplementary appendix 2). Subjects will be classified into peripheral neuropathic, nociceptive or central sensitisation musculoskeletal LBP according to criteria established by Smart et al.11–13 Each participant will be assigned randomly to either the experimental group which will receive PLFMF and the typical physical therapy programme used in our department or the control group which will receive sham PLFMF and the typical physical therapy programme used in our department. Patients will be asked to lie down on the magnetic mattress for 20 min/session, three sessions a week for a total of 18 sessions (6 weeks). In the treatment group, the BEMER mattress will be activated, whereas in the control group (placebo), no magnetic field will be generated. The typical physical therapy programme used in our department consists of:

Hot packs (to cover the lower back area) for 20 min;

Back, hamstring and calf muscles stretching (performed from the long sitting position)

Lumbar erector spinae muscles self-stretching;

Back muscles strengthening (back extension and bridging);

Abdominal muscles strengthening (posterior pelvic tilt and sit-ups);

Participants will be asked to hold the above positions for 5 s. Each exercise will be done five times per session with 1 min rest between any two repetitions.

bmjopen-2018-024650supp002.pdf (350.4KB, pdf)

Each session will last for 60 min as follows:

20 min for active PLFMF or placebo;

20 min for hot packs;

20 min for exercises.

Treating therapist will monitor adherence to the intervention sessions using a study calendar.

All patients will be evaluated at baseline, end of the third and the sixth week. To assess for effects persistence, participants will be evaluated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks after completing the 6-week treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participation in the two-arm randomised double-blind trial evaluating the efficacy of PLFMF therapy on CLBP. CLBP, chronic low back pain; PLFMF, pulsed low-frequency magnetic field.

Outcome measures

-

NRS: Pain severity will be measured by the NRS. It is an 11-point numeric scale with one extreme labelled as no pain (0) and the other extreme worst pain imagined (10). It is a valid and reliable scale.51 The patient will be asked to indicate the level of his/her pain immediately before the session and 5 min after the intervention.

The percentage change in pain will be calculated at each post-baseline assessment as:

Short Form 36 (SF-36): An Arabic version of the SF-36 will be used to assess the quality of life of all participants. The validity and reliability of the Arabic versions of the SF-36 was established in a sample of Saudis.52

Disability measurement using the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ): It is a self-reported, condition-specific questionnaire which consists of 24 questions. It is often used to assess LBP disability. It was translated and adopted into Arabic language.53

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS 21): It is a 21-question scale which assesses the emotional state of depression, anxiety and stress. Each question is assessed in a four-point likert scale. The validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the scale has been established.54

Function measurement will be assessed using Patient Specific Functional Scale : It is a valid and reliable measure for physical function in musculoskeletal conditions.55 56 It measures 3–5 physical activities which are important to the patient and s/he is unable to do without difficulties. Patients rate the difficulty with which they do the function in an 11-point likert scale from 0 (unable to do) to 10 (not at all affected).

Global perceived effect (GPE) of condition change: It is a one-question scale which asks the patient to rate improvement/deterioration numerically from −5 (much worse) to 5 (much better). It is has been recommended as one of the outcomes in clinical trials that study chronic pain.57 The scale validity and reliability has been established.58

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): It is a 19-item questionnaire which assesses several aspects of sleep quality (sleep duration, disturbances, quality, efficiency, sleep onset latency, medication and daytime dysfunction). A global score of sleep quality is the sum of the various components of the questionnaire. The higher the score the worse the sleep quality. The questionnaire was translated and validated into Arabic language.59

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS): It is a 21-item questionnaire which evaluates the fatigue effects on quality of life in patients with chronic diseases. A likert scale from 0 (no effect of fatigue) to 4 (maximum effect of fatigue) is used to score each item of the questionnaire.

Safety measures

PLFMF has no known side effects; however, long-term side effects of PLFMF have not been evaluated. If side effects developed or the symptoms of any participants get worse during the study or the follow-up period s/he will be given appropriate medical care until the situation is resolved. Such participants will be withdrawn from the trial, if necessary. Any observed side effects will be recorded and reported to the IRB office at IAU.

Privacy and confidentiality

Screening, assessment and treatment will be done in a private area at King Fahd Hospital of the University in the department of physical therapy. Data will be coded, only one of the researchers will have the key for the codes. All data will be saved in a secured computer protected with a password. Only the researchers will have access to data. On report writing and professional publication, data will be presented collectively, none of the participants’ identity will be identified.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of this study protocol. However, the obvious lack of satisfactory treatment of CLBP was a major motivator for the study team to develop and conduct this study. The finding of the present study will be disseminated to the participants and the community in general through newsletters and presentations in the community.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial was approved by the IRB of IAU (IRB‐ 2017‐03–129). Any amendment to the protocol which may impact the conduct of the study will be approved by the IRB at IAU before implementation. The trial is also registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (Registration Number ACTRN 12618000921280). The trial was registered 31 May 2018. While the trial being conducted, the monitoring office for research and research ethics at King Fahd Hospital of the University (where the study will be conducted) will monitor the various milestones of the trial. The study will be explained to all participants by one of the researchers. All participants will sign a consent form before the beginning of any procedures of the study.

The results of the present trial will be presented in international conferences and will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Deanship of Research at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University for funding this clinical trial (Grant Number 2017-308-CAMS).

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept, design and drafting of the manuscript: FAA and SA. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: MSA, FA and HK. SL contributed to the statistical design and data analysis. All authors critically read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Deanship of Research, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University Grant Number 2017-308-CAMS.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Balagué F, Mannion AF, Pellisé F, et al. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2012;379:482–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60610-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017;6736:30970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028–37. 10.1002/art.34347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amirdelfan K, McRoberts P, Deer TR. The differential diagnosis of low back pain: a primer on the evolving paradigm. Neuromodulation 2014;17(Suppl 2):11–17. 10.1111/ner.12173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johansson MS, Jensen Stochkendahl M, Hartvigsen J, et al. Incidence and prognosis of mid-back pain in the general population: A systematic review. Eur J Pain 2017;21:20–8. 10.1002/ejp.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saragiotto BT, Maher CG, Yamato TP, et al. Motor control exercise for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;1:CD012004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J 2008;8:8–20. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maniadakis N, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain 2000;84:95–103. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low Back Pain. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2001;344:363–70. 10.1056/NEJM200102013440508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, et al. Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 1 of 3: symptoms and signs of central sensitisation in patients with low back (± leg) pain. Man Ther 2012;17:336–44. 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, et al. Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 2 of 3: symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back (± leg) pain. Man Ther 2012;17:345–51. 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, et al. Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 3 of 3: symptoms and signs of nociceptive pain in patients with low back (± leg) pain. Man Ther 2012;17:352–7. 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krammer A, Horton S, Tumilty S. Pulsed electromagnetic energy as an adjunct to physiotherapy for the treatment of acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. N Z J Physiother 2015;43:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bronfort G, Nilsson N, Haas M, et al. Non-invasive physical treatments for chronic/recurrent headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3:CD001878 10.1002/14651858.CD001878.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, et al. Manipulation and mobilization for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J 2018;18:866–79. 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Majchrzycki M, Kocur P, Kotwicki T. Deep tissue massage and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. Scientific World J 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/287597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seco J, Kovacs FM, Urrutia G. The efficacy, safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound and shock wave therapies for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2011;11:966–77. 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi HK, Gwon HJ, Kim SR, et al. Effects of active rehabilitation therapy on muscular back strength and subjective pain degree in chronic lower back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2016;28:2700–2. 10.1589/jpts.28.2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cruz-Díaz D, Romeu M, Velasco-González C, et al. The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:1249–57. 10.1177/0269215518768393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacPherson H, Vickers A, Bland M, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain and depression in primary care: a programme of research. Programme Grants for Applied Research 2017;5:1–316. 10.3310/pgfar05030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:276–86. 10.7326/M14-2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mika J, Zychowska M, Makuch W, et al. Neuronal and immunological basis of action of antidepressants in chronic pain - clinical and experimental studies. Pharmacol Rep 2013;65:1611–21. 10.1016/S1734-1140(13)71522-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coutinho AD, Gandhi K, Fuldeore RM, et al. Long-term opioid users with chronic noncancer pain: Assessment of opioid abuse risk and relationship with healthcare resource use. J Opioid Manag 2018;14:131–41. 10.5055/jom.2018.0440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daniels CJ, Wakefield PJ, Bub GA, et al. A Narrative Review of Lumbar Fusion Surgery With Relevance to Chiropractic Practice. J Chiropr Med 2016;15:259–71. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee J, Shin JS, Lee YJ, et al. Long-Term Course of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS) Patients Receiving Integrative Korean Medicine Treatment: A 1 Year Prospective Observational Multicenter Study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170972 10.1371/journal.pone.0170972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McLean MJ, Holcomb RR, Wamil AW, et al. Blockade of sensory neuron action potentials by a static magnetic field in the 10 mT range. Bioelectromagnetics 1995;16:20–32. 10.1002/bem.2250160108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sisken BF, Midkiff P, Tweheus A, et al. Influence of static magnetic fields on nerve regeneration in vitro. Environmentalist 2007;27:477–81. 10.1007/s10669-007-9117-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morris CE, Skalak TC. Acute exposure to a moderate strength static magnetic field reduces edema formation in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008;294:H50–H57. 10.1152/ajpheart.00529.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weintraub MI, Wolfe GI, Barohn RA, et al. Static magnetic field therapy for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:736–46. 10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Robertson JA, Théberge J, Weller J, et al. Low-frequency pulsed electromagnetic field exposure can alter neuroprocessing in humans. J R Soc Interface 2010;7:467–73. 10.1098/rsif.2009.0205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Selvam R, Ganesan K, Narayana Raju KV, et al. Low frequency and low intensity pulsed electromagnetic field exerts its antiinflammatory effect through restoration of plasma membrane calcium ATPase activity. Life Sci 2007;80:2403–10. 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robertson JA, Juen N, Théberge J, et al. Evidence for a dose-dependent effect of pulsed magnetic fields on pain processing. Neurosci Lett 2010;482:160–2. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brook J, Dauphinee DM, Korpinen J, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency electromagnetic field therapy: a potential novel treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 2012;51:312–6. 10.1053/j.jfas.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khoromi S, Blackman MR, Kingman A, et al. Low intensity permanent magnets in the treatment of chronic lumbar radicular pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:434–45. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hedén P, Pilla AA. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields on postoperative pain: a double-blind randomized pilot study in breast augmentation patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2008;32:660–6. 10.1007/s00266-008-9169-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Negm A, Lorbergs A, Macintyre NJ. Efficacy of low frequency pulsed subsensory threshold electrical stimulation vs placebo on pain and physical function in people with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1281–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abdulla FA, Abualait T, Alkhamis F, et al. Effects of pulsed low frequency electromagnetic field on patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. In preparation 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oke KI, Umebese PF. Evaluation of the efficacy of pulsed electromagnetic therapy in the treatment of back pain: a randomized controlled trial in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. West Indian Med J 2013;62:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harden RN, Remble TA, Houle TT, et al. Prospective, randomized, single-blind, sham treatment-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of an electromagnetic field device for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Pain Pract 2007;7:248–55. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee PB, Kim YC, Lim YJ, et al. Efficacy of pulsed electromagnetic therapy for chronic lower back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Int Med Res 2006;34:160–7. 10.1177/147323000603400205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Omar AS, Awadalla MA, El-Latif MA. Evaluation of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy in the management of patients with discogenic lumbar radiculopathy. Int J Rheum Dis 2012;15:e101–e108. 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. W-h P, S-h S, S-g L, et al. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic field treatment on alleviation of lumbar myalgia. J Magn 2014;19:161–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, et al. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. JAMA 2012;307:1838–47. 10.1001/jama.2012.3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andrade R, Duarte H, Pereira R, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy effectiveness in low back pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Porto Biomed J 2016;1:156–63. 10.1016/j.pbj.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nayback-Beebe AM, Yoder LH, Goff BJ, et al. The effect of pulsed electromagnetic frequency therapy on health-related quality of life in military service members with chronic low back pain. Nurs Outlook 2017. 65:S26–S33. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gyulai F, Rába K, Baranyai I, et al. BEMER Therapy Combined with Physiotherapy in Patients with Musculoskeletal Diseases: A Randomised, Controlled Double Blind Follow-Up Pilot Study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:1–8. 10.1155/2015/245742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hug K, Röösli M. Therapeutic effects of whole-body devices applying pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF): a systematic literature review. Bioelectromagnetics 2012;33:95–105. 10.1002/bem.20703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Piatkowski J, Kern S, Ziemssen T. Effect of BEMER magnetic field therapy on the level of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:507–11. 10.1089/acm.2008.0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferraz MB, Quaresma MR, Aquino LR, et al. Reliability of pain scales in the assessment of literate and illiterate patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1990;17:1022–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coons SJ, Alabdulmohsin SA, Draugalis JR, et al. Reliability of an Arabic version of the RAND-36 Health Survey and its equivalence to the US-English version. Med Care 1998;36:428–32. 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maki D, Rajab E, Watson PJ, et al. Cross-cultural translation, adaptation, and psychometric testing of the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire into modern standard Arabic. Spine 2014;39:E1537–E1544. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ali AM, Ahmed A, Sharaf A, et al. The Arabic Version of The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21: Cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian J Psychiatr 2017;30:56–8. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gross DP, Battié MC, Asante AK. The Patient-Specific Functional Scale: validity in workers' compensation claimants. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1294–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berghmans DD, Lenssen AF, van Rhijn LW, et al. The Patient-Specific Functional Scale: Its Reliability and Responsiveness in Patients Undergoing a Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015;45:550–6. 10.2519/jospt.2015.5825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113:9–19. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kamper SJ, Ostelo RWJG, Knol DL, et al. Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:760–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Suleiman KH, Yates BC, Berger AM, et al. Translating the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index into Arabic. West J Nurs Res 2010;32:250–68. 10.1177/0193945909348230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024650supp001.pdf (149.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024650supp002.pdf (350.4KB, pdf)