Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to explore health professionals’ perception of risk factors related to child maltreatment in China.

Design

Qualitative research.

Setting

The study was conducted in November and December 2014 in Hunan, Zhejiang, Shaanxi and Guangdong provinces in China.

Participants

Five urban communities and five rural communities were randomly selected in each province, and interviews were conducted in maternal and child health hospitals, children’s hospitals, community health service centres and township hospitals in the selected areas. Doctors, nurses and administrators involved in child healthcare services were selected for in-depth-interview.

Results

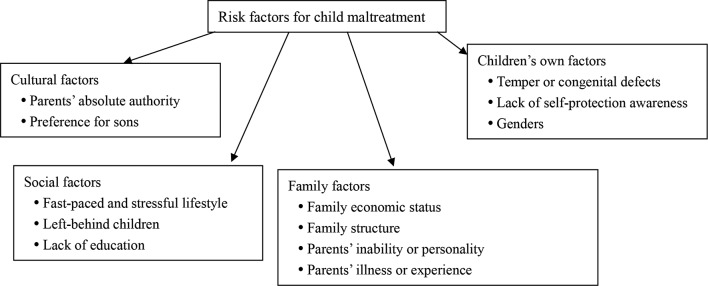

A total of 102 health professionals were approached but 95 completed the interview. From their perspective, risk factors causing child maltreatment were categorised into four domains: (1) cultural factors, including parents’ absolute authority over their children and son preference; (2) social factors, including a fast-paced and stressful lifestyle, children left behind by migrant worker parents and lack of quality child care and education; (3) family factors, including economic status, family structure, parents’ inability to provide parental care, experience of maltreatment and parents’ illnesses; (4) children’s factors, including gender, temper, disabilities and poor awareness of self-protection.

Conclusions

The results indicate that health professionals in China are aware of certain risk factors for child maltreatment; however, some views are outdated and wrong. Based on the perception of health professionals, targeted training courses are needed to enable them to correctly identify and deal with suspected cases of child maltreatment.

Keywords: China, child maltreatment, risk factor, health Professionals

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses qualitative research method to explore health professionals’ perception of risk factors related to child maltreatment in China.

This study is an important attempt to carry a step forward toward child maltreatment prevention programmes in China.

A limitation of this qualitative study is that it only reflects the population studied.

Introduction

According to the WHO, child maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligent treatment, commercial and/or other exploitation that occurs to children under 18 years of age.1 2 The consequences of child maltreatment are more wide-ranging than death and injury.3 For instance, child maltreatment has been associated with a myriad of adverse consequences throughout children’s lifespan, including harm to the victim’s physical and mental health, life quality, well-being and development.4 5 It also leads to a huge financial burden on individuals, families and the country.6

Although most studies on child maltreatment have been conducted in developed countries, child maltreatment is common throughout the entire world.7 8 In China, child maltreatment, as defined by WHO, was not recognised as a social problem until the early 1990s, but prevalence has been increasing.9 Although China is a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, neither a formal child protection system nor a network of social services exist to support ‘at risk’ families.10 A recent literature review reported the prevalence of physical abuse lies between 32.4% and 67.3%, sexual abuse between 10.2% and 25.5%, emotional abuse between 10.6% and 67.1%, and neglect between 22.4% and 54.9% reported by different researchers in China.11

Since late 1990s, the Chinese government has been working to strengthen the child protection system through various efforts. Under a policy titled the ‘Equalization of Basic Public Health Service’, community and township healthcare centres provide free basic healthcare services for children aged 0–6 years, including medical examination, nutrition advice and a feeding guide, and psychological development assessment.12 Under this policy, healthcare professionals can play a key part in identifying, dealing with and reporting maltreatment cases, as well as providing referrals that can prevent further maltreatment.6 13 In 2016, the National People’s Congress issued the ‘Anti-domestic Violence Law’, in which any forms of maltreatment including corporal punishment are prohibited. Under the regulation of this law, healthcare professionals at all levels have the legal responsibility to report any potential child maltreatment cases to the police authority. Healthcare workers are placed in a position that requires them to identify and report potential child maltreatment cases. Their knowledge and attitudes are essential factors in fulfilling these obligations.12

Preventing child maltreatment requires a diverse approach across different sectors, and only with knowledge of risk factors can interventions be designed.1 3 Thus, this study aimed to explore health professionals’ perception of risk factors related to child maltreatment in China so that targeted training courses can be developed to help health professionals identify and intervene child maltreatment.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in November and December 2014 in Hunan, Zhejiang, Shaanxi and Guangdong provinces. A multistage sampling method was used to select study participants. One city (urban) and one county (rural) were randomly selected in each province, and five communities in the city and five townships in the county were randomly selected. Interviews were conducted in maternal and child health hospitals, children’s hospitals, community health service centres and township hospitals in the selected areas. Doctors, nurses and managerial staff engaged in child healthcare services were approached to participate. This study has been reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of National Center for Women and Children’s Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sampling procedures

A combination of convenience sampling and sampling with a purpose were used. The first stage involved the selection and approaching of key informants, most of whom were administrators from the above-mentioned health facilities. As the second stage, with the help of key informants, the selection involved a purposeful sampling framework including variables such as occupational categories, type of departments and professional levels. The sampling process stopped when no new themes emerged during the interviews and an acceptable interpretative framework was constructed.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient and public involvement.

Data collection

The study collected qualitative data using in-depth interviews with a semistructured interview outline. The themes included current situation of child maltreatment, reasons for children to be maltreated and suggestions on healthcare worker’s role in maltreatment prevention. Each interview was conducted in a private room on a one-to-one basis in the health provider’s office or any other places according to the participant’s request. The interviewers were members of our research team who had experience of in-depth interview. A written consent was obtained before each interview. The duration of each interview ranged from 45 min to 1.5 hours. All interviews were recorded.

Data analysis

MAXQDA (version 11.0) was used to facilitate the data analysis. All interviews were transcribed by the fourth author, and the quality of the transcription was double-checked by the third author. The transcripts were coded and analysed by the second author. After careful and repeated examination of the transcripts, categories and subcategories of analysis were developed. Totally 24 codes and 11 code families were created. This made it easier to analyse by individual family code as well as visualise the relations among codes in a network.14 A constant comparative method was employed to facilitate theme development, following recommended steps.15 All codes relevant to perceived risk factors were searched and results categories were determined based on common themes across related codes. The coding strategy and procedure were double-checked by the first author to reach a consensus on the results.

Results

Sample characteristics

Hundred and twelve healthcare workers were approached. Two of them declined and five did not complete the interview due to emergency medical cases that need them to deal with. Table 1 summaries the demographic variables of the interviewees. The participants included 95 medical workers, with 40 males and 55 females. Most interviewees were doctors (65.3%). The participants from general hospitals (32.6%) were almost as many as those from maternal and child health hospitals (33.7%). Maternal and child health hospitals provide the majority of secondary care for children, with children’s hospitals offering tertiary care. Thus, only one children’s hospital served the population was interviewed. As for professional level, most interviewees held senior levels (47.4%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of health professionals completed the in-depth interview

| Male (n=40) |

Female (n=55) |

Total (N=95) |

% | |

| Province | ||||

| Zhejiang | 10 | 14 | 24 | 25.3 |

| Guangdong | 12 | 12 | 24 | 25.3 |

| Shaanxi | 10 | 13 | 23 | 24.2 |

| Hunan | 8 | 16 | 24 | 25.3 |

| Hospital level | ||||

| General hospital | 11 | 20 | 31 | 32.6 |

| Children’s hospital | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.1 |

| Maternal and child health hospital | 16 | 16 | 32 | 33.7 |

| Community health service centre | 7 | 15 | 22 | 23.2 |

| Township hospital | 5 | 3 | 8 | 8.4 |

| Occupational category | ||||

| Doctors | 25 | 37 | 62 | 65.3 |

| Nurses | 0 | 9 | 9 | 9.5 |

| Managers | 15 | 9 | 24 | 25.3 |

| Professional level | ||||

| Senior | 20 | 25 | 45 | 47.4 |

| Intermediate | 14 | 18 | 32 | 33.7 |

| Primary | 6 | 12 | 18 | 18.9 |

Risk factors for child maltreatment

Analysis of the interview transcriptions yielded four primary themes relevant to risk factors for child maltreatment: (1) cultural factors, (2) social factors, (3) family factors and (4) children’s own factors. These four primary themes were divided into subthemes to elucidate pertinent aspects (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Primary themes with subthemes summarised on the perceived risk factors for child maltreatment.

Cultural factors

In Chinese traditional culture, parents have absolute authority over their children and children’s disobedience is strictly forbidden. Under the influence of some typical Chinese traditional phrases, such as ‘Spare the rod and spoil the child’, parents tend to beat their children at will.

Influenced by the utilitarian atmosphere, many parents keep up with the Joneses by setting unreasonable expectations and demands for their children, and physically punish their children if they fail to meet these expectations.

Some parents’ expectations for their children are too high. They feel disappointed if children failed to achieve, which causes physical abuse. (Community health worker, female, aged 28)

The traditional preference for sons in China leads to maltreatment of girls, including physical abuse and neglect.

People living in remote or mountainous areas prefer boys to girls. In these families, giving birth to girls is contrary to their expectation, which might resulting in neglect or abuse. (Doctor in children’s hospital, male, aged 35)

Social factors

The pace of life in modern China is much faster than before, and some people bear heavy life stress as the society moves toward a highly commercial one. Parents at work have relatively limited time and patience to take care of their children.

Most parents working in cities or farming in rural areas have limited time and energy [to accompany their children]. (Community health worker, female, aged 36)

Some children are left in the care of grandparents or other relatives when their parents migrate to the cities for work. These children are more likely to suffer from maltreatment.

[In our village], most of them (children) are living with their grandparents, and comparatively can’t be supervised effectively. (Community health worker, male, aged 38)

Family factors

Families’ economic status may exert great impact on children’s well-being. Child maltreatment happens relatively more frequently in families with poor economic conditions. Children of single parents or in combined families tend to be at greater risk of maltreatment.

Child maltreatment is related to economic conditions …. One grandma [in my village] had no money and tried to relieve her stress by abusing the child. (Nurse in maternal and child health hospital, female, aged 32)

Sexual abuse might be committed by the stepfathers… Some stepmothers refuse to provide meals [for the children], and even beat them when their father is not at home. (Manager in maternal and child health hospital, female, aged 45)

Education also plays a large role. As some parents lack parenting skills, they think only physical punishment will make children more obedient.

Many of these parents believe children tend to remember what parents say after being beat rather than reasoning. (Doctor in maternal and child health hospital, male, aged 30)

Maltreatment is more likely to be committed by parents suffering from mental health issues, and parents who experienced maltreatment themselves when they were young.

As he [the father] was often physically punished at school age, he copies this behavior to his child now. (Nurse in children’s hospital, female, aged 35)

Children’s own factors

Children who are mischievous, bad-tempered or congenitally handicapped are more likely to suffer from maltreatment.

Sometimes it’s because the child is too naughty. They [the children] are also at risk of being maltreated if they have congenital defects. Another issue is the intelligence of children. (Manager in maternal and child health hospital, male, aged 41)

Some interviewees mentioned that children’s lack of self-protection awareness, and even being completely unaware of being maltreated, increases the risk of maltreatment.

Children of different genders are differently at risk for maltreatment. Girls are more likely to suffer from maltreatment, except when children have disabilities, in which case both genders are equally at risk.

I think girls are more likely to suffer from sexual abuse and neglect than boys… For children with congenital defects, the possibilities for boys and girls are more or less the same. (Manager in community healthcare centre, female, aged 40)

Discussion

Our study identified the risk factors of child maltreatment in China as perceived by health professionals. Given their unique relationship with children and families, health professionals should be alerted to risk factors that may suggest suspected cases. There is a direct association between the act of reporting cases and matters related to knowledge.16 We found that in the view of Chinese health professionals, many factors might increase the risk of child maltreatment, including cultural, social, family factors and those of the child itself.

Cultural factors are very important in understanding child abuse. In Chinese tradition, the experience of deliberately inflicted pain is regarded as character-building.17 Chinese people seem to be less critical of the use of physical force by parents to accomplish desired ends.18 The traditional value of filial piety (Xiao) gives parents absolute authority over their children. This is why children’s disobedience toward parents is the most common reason for physical punishment.19 Additionally, under the one-child policy launched in 1979, parents tend to attach higher value and put greater expectations on children, and punish them once the expectations fail to be met.20 Although in 2013 China announced the decision to relax the one-child policy and encourage families to have two children if one parent was an only child, tension between the child and parents caused by high expectations is still a risk factor of disciplinary punishment.

In China, conventional wisdom that sons are preferable to daughters is embedded within patrilineal family structures.21 Although the inherent son preference is on decline, sons are still desired more frequently than daughters.22 Deep-rooted Confucian values play a part.23 In addition, with rapid economic development in China, the pace of live and stress on parents has increased, which negatively affect parenting practices.9 The respondents have also recognised the children who are left behind when their parents go to work in cities. This is consistent with many studies exploring the influence of rural to urban labour migration.24 With the processes of modernisation and urbanisation, many children are left behind and should be given special attention.

The interviewees perceived low family economic status as a risk factor, which can affect the parent–child relationships by limiting economic resources and increasing parents’ stress levels.9 Instances of single parent families and combined families have been increasing in China. The financial stresses of being a single parent, social stresses due to isolation and a lack of social support all play a part in the increased risk in single parent families.25 When a single parent remarries, children may have difficulties in dealing with relationships with new family members, putting them at an increased risk of maltreatment. Previous studies reported a number of characteristics, including education level, lack of skills, patience or responsibility, were linked to child abuse. For example, parents with low education levels were reported in the literature to present a fivefold increase in risk.25 In another study, parents who were more likely to abuse children physically were found to have poor control of their impulses and mental health problems.26 All this indicated the necessity of parenting skill education. Health professionals need to make effort to build harmonised parent–child relationship and happier family environment.

It is clear that children are victims and cannot be blamed for the maltreatment suffered. However, children with several characteristics are more prone to maltreatment, including curiousness of young age, physical or mental handicaps, premature birth or low birth weight.25 While health professionals did not mention the latter two, they did identify poor awareness of self-protection and children’s character. This indicates that some health professionals misunderstood the underlying reasons by blaming children instead of perpetrators and show tolerance to maltreatment such as corporal punishment.

It has been a consensus that girls are at higher risk for sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect, whereas boys are more likely to be victims of physical abuse in many countries.8 Wide cultural gaps exist between different societies and studies in China produced mixed findings, with boys being more likely to experience both physical and emotional abuse.9 Boys may be at greater risk as they are perceived as inherently having greater responsibility for social obligations, support for parents and preserving family heritage.26 However, health professionals failed to realise the risk of boys’ abuse. Further research is still needed to validate the gender differences.

Conclusions

This study is an attempt to carry a step forward in terms of training health professionals in China. Training is required to increase knowledge of health professionals to help them understand the cause of child maltreatment and meet the qualifications to practice prevention and treatment of child maltreatment. The results of this study provide basis for developing targeted child maltreatment prevention training courses for health professionals. The results may also serve as a basis to develop appropriate interventions in areas with similar culture background.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ms CaiYue and Chen Xuemei from Unicef for providing technical support. We also thank all the health workers who participated in this study. We thank Ms Margaux Schreurs and Mrs Chunmei Li for the help with editing the language.

Footnotes

Contributors: The research design, data analysis and manuscript of this study were completed by TX and QY. The interview was completed by SW, YW, WL and XH. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The study was funded by Unicef Beijing Office.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set is the deidentified interview transcriptions of the 95 subjects (only in Chinese). Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Presented at: This study was accepted for oral presentation in the 2015 ISPCAN Asia Pacific Regional Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Child maltreatment. 2014. Geneva: WHO http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/en/.

- 2. World Health Organization. Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention. Geneva: WHO, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization & ISPCAN. Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: WHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiser LJ, Stover CS, Navalta CP, et al. Effects of the child-perpetrator relationship on mental health outcomes of child abuse: it’s (not) all relative. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38:1083–93. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sidebotham P, Heron J, Team AS; ALSPAC Study Team. Child maltreatment in the "children of the nineties:" the role of the child. Child Abuse Negl 2003;27:337–52. 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pietrantonio AM, Wright E, Gibson KN, et al. Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect: crafting a positive process for health professionals and caregivers. Child Abuse Negl 2013;37:102–9. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng JY, Levine M. Factors associated with nurses' intention to report child abuse: a national survey of Taiwanese nurses. Child Abuse Negl 2005;29:783–95. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Etienne G, Krug LLD, Mercy JA, et al. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liao M, Lee AS, Amelia C. Roberts-Lewis, Jun Sung Hong, Kaishan Jiao. Child maltreatment in China: An ecological review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review 2011;33:1709–19. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hesketh T, Hong ZS, Lynch MA. Child abuse in China: the views and experiences of child health professionals. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:867–72. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00139-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tao X, Fuyong J, Jianping P, et al. A systematic literature review of child maltreatment in China (in Chinese). Chinese journal of child health care 2014;22:972–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li X, Yue Q, Wang S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of healthcare professionals regarding child maltreatment in China. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:869–75. 10.1111/cch.12503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wekerle C. Resilience in the context of child maltreatment: Connections to practice. Child Abuse & Neglect 2013;37:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li L, Sun S, Wu Z, et al. Disclosure of HIV status is a family matter: field notes from China. J Fam Psychol 2007;21:307–14. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dye JF, Schatz IM, Rosenberg BA. Constant comparison method: A kaleidoscope of data. PracticingQualitative Research 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moreira GA, Vieira LJ, Deslandes SF, et al. [Factors associated with the report and adolescent abuse in primary healthcare]. Cien Saude Colet 2014;19:4267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DYH W. Child abuse in Taiwan Korbin JE, Child abuse and neglect: Cross-cultural perspectives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1981:139–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong GK, Hong LK. Comparative perspectives on child abuse and neglect: Chinese versus Hispanics and whites. Child Welfare 1991;70:463–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leung PW, Wong WC, Chen WQ, et al. Prevalence and determinants of child maltreatment among high school students in Southern China: a large scale school based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2:27–48. 10.1186/1753-2000-2-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hua J, Mu Z, Nwaru BI, et al. Child neglect in one-child families from Suzhou City of mainland China. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2014;14:8 10.1186/1472-698X-14-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy R, Tao R, Lu X. Son preference in rural China: patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Popul Dev Rev 2011;37:665–90. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou C, Wang XL, Zhou XD, et al. Son preference and sex-selective abortion in China: informing policy options. Int J Public Health 2012;57:459–65. 10.1007/s00038-011-0267-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Das Gupta M, Zhenghua J, Bohua L, et al. Why is Son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? a cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. J Dev Stud 2003;40:153–87. 10.1080/00220380412331293807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang X, Ling L, Su H, et al. Self-concept of left-behind children in China: a systematic review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:346–55. 10.1111/cch.12172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sidebotham P, Heron J, Team AS; ALSPAC Study Team. Child maltreatment in the "children of the nineties": a cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl 2006;30:497–522. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klevens J, Bayón MC, Sierra M. Risk factors and context of men who physically abuse in Bogotá, Colombia. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:323–32. 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00148-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.