Abstract

Introduction

The South African Department of Health has developed and implemented the Integrated Chronic Disease Management (ICDM) model to respond to the increased utilisation of primary healthcare services due to a surge of non-communicable diseases coexisting with a high prevalence of communicable diseases. However, some of the expected outcomes on implementing the ICDM model have not been achieved. The aims of this study are to assess if the observed suboptimal outcomes of the ICDM model implementation are due to lack of fidelity to the ICDM model, to examine the contextual factors associated with the implementation fidelity and to calculate implementation costs.

Methods and analysis

A process evaluation, mixed methods study in 16 pilot clinics from two health districts to assess the degree of fidelity to four major components of the ICDM model. Activity scores will be summed per component and overall fidelity score will be calculated by summing the various component scores and compared between components, facilities and districts. The association between contextual factors and the degree of fidelity will be asseseed by multivariate analysis, individual and team characteristics, facility features and organisational culture indicators will be included in the regression. Health system financial and economic costs of implementing the four components of the ICDM model will be calculated using an ingredient approach. The unit of implementation costs will be by activity of each of the major components of the ICDM model. Sensitivity analysis will be carried out using clinic size, degree of fidelity and different inflation situations.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by the University of Cape Town and University of the Witwatersrand Human Research ethics committees. The results of the study will be shared with the Department of Health, participating health facilities and through scientific publications and conference presentations.

Keywords: implement, ICDM, intervention evaluation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses implementation research principles to provide data on the degree of fidelity to the Integrated Chronic Disease Management (ICDM) model for optimising the model.

Process evaluation will provide an indication of how the ICDM model has been modified in different contexts and explain variability in the implementation outcomes.

Implementation cost assessments are essential in public health programmes to inform resource allocation during planning and budgeting and to inform economic evaluations.

The reliance on the service provider to accurately provide information on the implementation activities or insufficiencies of those activities is a limitation of this study.

Although the clinics may not be representative of all districts and clinics in the country, the results of this study could be applied to clinics similar in size or patient load and other integrated disease management models.

Introduction

Chronic diseases and multimorbidity are increasing in developing countries due to epidemiological transition of increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the presence of rampant infectious diseases.1 2 By 2025, it is estimated that the burden of NCDs in sub-Saharan Africa will be higher than that of communicable diseases (CDs).3 The increase in urbanisation, economic development, ageing, decrease in physical activity and poor dietary options are some of the contributing factors to the increasing prevalence of NCDs in developing countries.4 5 There is also a complex interaction of risk factors, management and health outcomes between NCDs and CDs, resulting in a rise in chronic disease multimorbidity.6 7 Multimorbidity often results in reduced levels of physical capability, high rates of health services utilisation and attendant costs and higher mortality rates.8 9 The double burden (NCDs and CDs) of diseases is costly to the health systems (increased utilisation, medication), the economies, households and individuals.2 Therefore, chronic disease management needs to be comprehensive and take into consideration these interactions in disease prevention, management and control.

In South Africa, the current leading health problems are NCDs, accounting for 51.3% of all deaths, followed by CDs 38.4% and injuries 10.3%.10 South Africa like many Sub-Saharan African countries has been severely affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with 7.1 million people living with HIV and 18.9% of people between the ages of 15 and 49 years being HIV infected.11 As a result, there is an increase in the prevalence of multimorbidity.12 Tuberculosis, HIV and NCDs (mainly hypertension and diabetes mellitus) account for 45% of all primary healthcare consultations, with a multimorbidity prevalence of 22.6%.9 13

Unresponsive health systems often provide services that are not aligned with the health requirements of the population being served.14 A more comprehensive chronic disease management model, combining both CDs and NCDs that reduces health utilisation and promotes self-management, is one of the strategies that have been recommended to address the challenges associated with the management of multimorbid chronic diseases.2 14 The Chronic Care model and Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions framework have been recommended as health system approaches to deal with multimorbidity.15 However, there have been significant resources and strategies allocated to the implementation of HIV programmes and consequently the non-communicable chronic diseases have been overlooked. To rectify this imbalance, the South African National Department of Health developed and has begun implementation of the Integrated Chronic Disease Management (ICDM) model in order to improve efficiencies and quality of care in primary healthcare clinics for patients with chronic diseases.16

Integrated Chronic Disease Management model

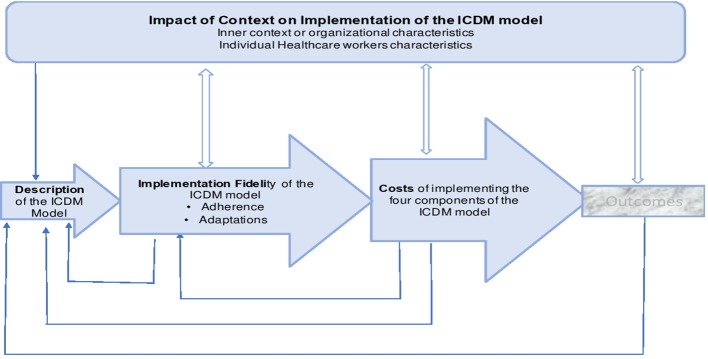

The ICDM model was piloted from 2011 in 42 clinics from three health districts in three different provinces (figure 1) of South Africa as follows: West Rand in Gauteng Province, Bushbuckridge in Mpumalanga and Dr Kenneth Kaunda in North West Province.17 18 As part of a broader national approach to revitalise primary healthcare (PHC) services, reduce fragmentation of services and ensure that each PHC facility meets national minimum standards, the ‘ideal clinic’ initiative was also started in 2019.19 The principles of the ‘ideal clinic’ incorporate the majority of the activities required for ICDM implementation and provide standard operating procedures for the Ideal Clinic Realisation and Maintenance (ICRM) programme.20 21 One of the components of the ICRM programme is Integrated Clinical Services Management (ICSM), which focuses on health services being structured in four (acute, chronic, preventive and promotive and health support) streams.20 21 The principles of the ICRM, ICSM and the ICDM model cover integration of services, good administrative processes, functional infrastructure and equipment, adequate personnel, ensuring adequate levels of medicines and supplies and the use of applicable protocols and guidelines in diseases management.19–21

Figure 1.

Map of South Africa with the Integrated Chronic Disease Management model pilot sites highlighted.

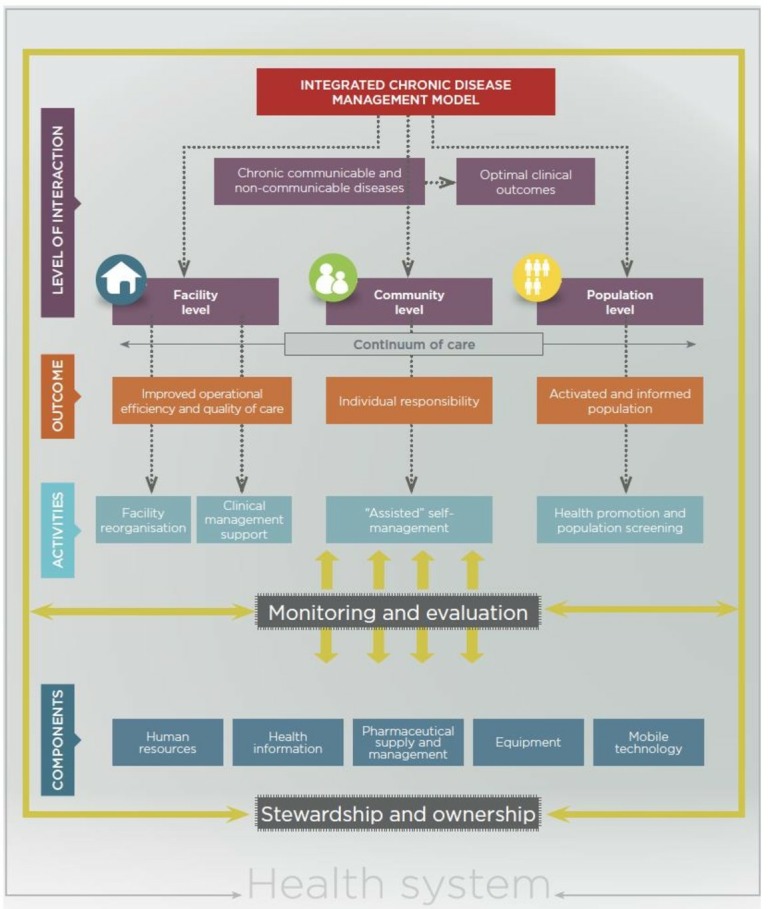

The four major components (action points) of the ICDM implementation are as follows: facility reorganisation for efficiency, clinical supportive management, assisted self-support and strengthening of support systems (figure 2).16 The ICDM priority and core standards are (1) improving the values and attitudes of staff, (2) patient safety and security and infection prevention and control and (3) availability of medicines and supplies.16 Assuming full implementation of the ICDM as recommended, the expected outcomes include improved operational efficiency and quality of care, improved individual responsibility towards their health and an activated and informed community.16 The ICDM model also provides guidelines on booking systems for patients with chronic diseases, clinic flow, organisation of waiting areas and consultation rooms and dispensing medication practices that promote adherence and minimise medication shortages. In order to avoid fragmentation of services, the ICDM recommends a multidisciplinary treating team to provide care to all patients with chronic illnesses and be trained on how to assess and manage drug-drug interactions and disease interactions. Mentoring, supervision and training of the PHC nurses to be provided by the district Clinical Specialist Team (DCST).16 The DCST’s other responsibilities include monitoring of patient clinical outcomes through clinical audits and strengthening of referral systems for complicated patients.16 The components or building blocks for ICDM model include human resources, health information, mobile technology, equipment and pharmaceutical supply and management.16

Figure 2.

Integrated Chronic Disease Management model.16

ICDM model pilot phase implementation

The pilot phase was supported with quality improvement reviews and consultation with all staff members at the facility, district and province levels to refine the model even further.18 Some of the implementation challenges identified in these consultations were lack of key equipment, an emphasis on curative health services with minimal focus on prevention, the ill-defined role of community healthcare workers and delayed formation of out-of-facility chronic medication collection sites.18 Lack of these necessary building blocks for the ICDM model has resulted in the implementation of hybrids of the original model.18 The limitations of the ICDM model identified include its focus on secondary and tertiary prevention of disease within the healthcare facilities and the lack of guidelines on social and environmental changes for the prevention of risk factors and onset of chronic diseases.16

Management of chronic conditions in PHC facilities

An evaluation of PHC services in South Africa showed low rates of diagnosis for chronic diseases, and the few that are diagnosed are not managed appropriately and do not achieve the treatment targets.22 23 The lack of key equipment in PHC clinics to diagnose and monitor total cholesterol, blood pressure and blood glucose contribute to these challenges, with patients reporting the need to travel to higher levels of care to access certain medication and diagnostic tests.22 Additional barriers included the insufficient consultation time that patients report with their healthcare providers even after long waiting periods at the facility due to high volumes of patients22; poor knowledge on chronic disease, shortage of medication and shortage of healthcare workers resulting in long waiting periods at PHC clinics.24 The nurses knowledge of chronic diseases was also found to be poor due to inadequate training, unavailability of guidelines and lack of supervision.24

The implementation of an innovative intervention can be affected by the design of the intervention, context and/or implementation outcomes.25 New innovative interventions could fail to achieve intended objectives because of implementation barriers or failures in the design.25 The observed impact of the ICDM model in the management of chronic diseases has been an improvement in the patients’ records, compliance with clinical guidelines and health outcomes for patients on antiretroviral medication but not those on hypertension treatment.26 27 Irregular supplies and stock-outs of hypertension medication were also not improved after the implementation of the ICDM model.28 The patients’ perspectives on the ICDM model inconveniences were a non-flexible appointment system that affected access to services, long waiting times because of personnel shortages and stigmatisation of patients that are visited by community healthcare workers.28 However, it is not clear whether these observed and perceived gains and shortcomings are as a result of the inherent faults in the design of the model or failure to adhere to the prescribed activities and/or the impact of contextual factors.

The successful implementation of the ICDM model requires a high degree of fidelity to the recommended processes of delivering healthcare services with clear intervention priorities and expected outcomes.29 30 Although monitoring and evaluation tools exist for the ICDM model implementation, they do not provide data on implementation outcomes such as adoption, fidelity, penetration, acceptability, sustainability and costs. Process evaluation of the ICDM model implementation would optimise practice of the four major components and scale-up of the model, and the quality of care for individuals affected by chronic illness, especially those with multimorbidity.

Implementation of any intervention within a large complex health system is generally unpredictable. An assessment of fidelity on the implementation of the model will additionally measure quality of practice for continuous improvement, identify any innovations that can improve models’ processes and support systematic implementation of the model. Although the implementation of the ICDM model was subsequently followed by the ICRM programme that consists of the ICSM, which has a broader focus beyond chronic diseases, both these interventions have similar principles, standards and aims of ensuring that patients get quality patient-centric care that achieves the desired health outcomes.19–21 We envisage that lessons learned from an evaluation of the ICDM model can be beneficial in the strengthening of implementation of the ICRM programme.

Interviews with the actors in the ICDM model implementation will provide information on their perceptions and experiences with implementation and how contextual factors have affected fidelity to the model’s guidelines. This can improve comparability, generalisability and replicability of the results of this study. Assessing the cost of implementing the various activities of the ICDM model will then assist with planning and budgeting, as well as inform scalability and sustainability of the model.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate selected implementation outcomes of the ICDM model: fidelity and implementation costs, and to assess the influence of contextual factors on ICDM model implementation fidelity in two health districts where the ICDM has been piloted, from two different provinces in order to better understand the processes of successful implementation of the ICDM model and how the model can be optimised. The objectives of the study are as follows:

To assess the degree of fidelity in the implementation of the ICDM model.

To evaluate the influence of contextual factors on the implementation fidelity of the ICDM model.

To estimate the implementation costs of the ICDM model.

Methods and analysis

Setting

This study will be conducted from August 2018 to July 2019 in two health districts (Dr Kenneth Kaunda in North West Province and West Rand District in Gauteng) that were the pilot sites for the ICDM model implementation. Both districts are within socioeconomic quantile 4 (1 is most deprived and 5 is least deprived); however, comparing the North West to Gauteng province, poverty prevalence (33% vs 27%) and informal housing (21% vs 19%) are slightly higher in the North West Province.31 32 The provincial HIV prevalence is 13.3% in North West Province and 12.4% in Gauteng.33 The prevalence of hypertension is high (31%–39.7%) in both districts, a reflection of large number of people accessing health services for chronic NCD.31 The prevalence of diabetes in South Africa is 8.27% (2.6 million) and 31.9% among adults (20–79 years), with 1.2 million people with diabetes estimated to be undiagnosed.34

Theoretical framework

Process evaluation of complex interventions

Process evaluation frameworks assist in understanding the functioning of a complex intervention by reviewing implementation processes and the influence of contextual factors.35 36 A complex intervention implementation process has multiple components, which interact to produce change, and/or are difficult to implement and/or target a number of organisational levels.35 37 Process evaluation is therefore useful for assessing (figure 3) fidelity (dose, adaptations, frequency and reach), clarifying the usual mechanisms and processes and identifying the impact of contextual factors on the variations in processes and outcomes.38 A process evaluation framework will be applied in this study to evaluate whether the processes for implementing the intervention (the ICDM model) are being applied as intended according to the design (fidelity) of the intervention and how contextual factors influence the implementation fidelity (figure 4). The costs, quantity and quality of programme activities provided and evaluating the generalisability of the results in other different contexts are important especially for a programme that is already established.38

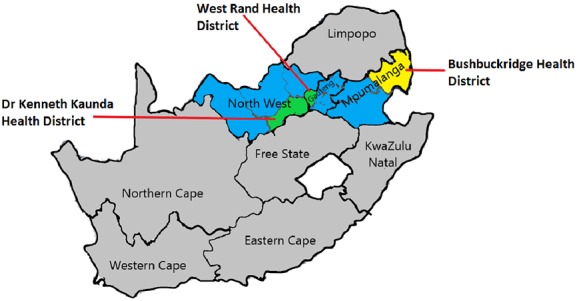

Figure 3.

The process evaluation framework for complex interventions.38

Figure 4.

Modified process evaluation framework for assessing the fidelity and cost of the ICDM model implementation. ICDM, Integrated Chronic Disease Management.

Study design

This is a process evaluation study using mixed methods to assess the degree of fidelity, costs and impact of context on the implementation fidelity of the ICDM model.

Objective-specific methodology

Fidelity assessment will be carried out to review if implementation of the ICDM model adheres to content, coverage, frequency and duration as prescribed in the ICDM model manual in 16 (8 in North West and 8 in Gauteng) clinics. As there are no fidelity criteria in the literature that are suitable to adapt for assessing the ICDM model implementation, we developed fidelity criteria based on the ICDM model guidelines,16 the ICRM programme monitoring tools21 and published literature on the ICDM model.18 26 28 30 The basis of the criteria are the four (facility reorganisation, clinical supportive management, assisted self-management and strengthening of the support systems) major components of the ICDM model.16 The outlined prescribed activities are the variables to be assessed on the implementation fidelity criteria. The expected outcome of the fidelity criteria is to warrant that all the essential activities required for successful implementation of the ICDM model have been captured. Each criterion under the four major components will be listed as an item to be scored on the fidelity criteria. We will assess the fidelity criteria in a pilot study and finalise it on the basis of the results of the pilot study. Sixteen clinics from the 20 ICDM pilot clinics located in those districts will be considered for inclusion if the clinic has been open and running without any major interruptions (renovations, closures) in the last 2 years. At each clinic, we will collect data using structured observations, review of facility records and interviews with the healthcare workers (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of study objectives, methods and expected outcomes for assessing the fidelity, impact of contextual factors and costs of implementing the ICDM model

| Objective | Methods | Outcomes | |

| Degree of fidelity assessment | To assess the degree of fidelity in the implementation of the ICDM model | Quantitative: fidelity evaluation in 16 ICDM model pilot PHC clinics using the fidelity criteria scoring checklist template. Data sources: key informant interviews, structured observations and review of facility records |

Degree of the ICDM model implementation fidelity for each activity and component of the ICDM model and overall scores by clinic and district |

| Impact of contextual factors on ICDM fidelity | To evaluate the influence of contextual factors on the implementation fidelity of the ICDM model | Qualitative interviews with 30 HCW in four (two per district) facilities using structured interview guides and organisational culture survey. Quantitative data to assess association between contextual factors and degree of ICDM model fidelity |

Health workers’ perceptions of contextual factors that influence implementation fidelity of the ICDM model. Establish influence of contextual factors on the degree ICDM model implementation fidelity |

| Costs of implementing the ICDM model | To estimate the implementation costs of the ICDM model | Ingredient approach to health system costs in four PHC clinics—two facilities per district using The WHO CostIt software 2007. Data sources: budgets, key informant interviews, direct observations and literature search. Annualise capital costs Adjust all costs for inflation and discount Develop a cost profile for providing each component of the ICDM model |

The cost of implementing each of the components of the ICDM model. Sensitivity analysis to determine cost drivers in the implementation of the ICDM model. |

ICDM, Integrated Chronic Disease Management; PHC, primary healthcare.

Contextual factors (facility characteristics and characteristics of individuals and teams) on fidelity will be examined in four clinics. Based on the degree of fidelity, two clinics, one with a high and one with a low degree of fidelity, will be selected from each of the two districts. The organisational contextual factors to be considered include communication style, decision process and culture.39 Individual level data for the implementing teams will include demographics (age, gender, race, education level), position role within the clinic, years in that role and their participation in the delivery of the ICDM model. External (to the facility) context factors (socioeconomic level, policies and legislation) will not be evaluated in order to keep the study scope manageable. We will use mixed methods (interviews, facility assessments and culture surveys) approach to assess the influence of context on implementation fidelity. We will conduct qualitative interviews with 30 healthcare workers, purposively selected to represent different cadres of staff members that implement and manage the ICDM model intervention for more than 6 months (table 1). The interviews will be done on a one-to-one basis to minimise having group dynamics.

Participants’ confidentiality will be protected at all times during the study, and no electronic record will contain individual identifiers. A master list that contains the participants’ identifiers will be kept in a separate lockable area. The results will also be presented in such a way that respondents cannot be identified.

Costs

The financial and economic costs of implementing the ICDM model from the health system perspective will be evaluated in the same four clinics. The health system implementation costs are an all-inclusive costing valuation that considers costs incurred by the providers of the service.40 Assessing the implementation costs will be a partial economic evaluation as it will only focus on the costs of implementation and not the outcomes. The unit of implementation costs will be by activity of each of the major components of the ICDM model. Service level costs such as those pertaining to the development of the ICDM model will not be included as these costs were incurred in 2010/11. The focus will be on post start-up annual costs required for the full implementation of the ICDM model in a typical year (table 1). Both direct and indirect, and fixed and recurrent costs will be calculated.

Capital costs

Annualised equipment and capital costs will be calculated according to the volume being used for the ICDM model. Estimating annual costs will include adding up the acquisition, operation, maintenance and disposal costs.

Operational costs

In the financial documents review, key operational costs that we will check and categorise include human resources, office supplies and travel. Based on the useful life and the discount rate, an appropriate annualisation factor will be determined. If there are any donations for programme implementation (volunteers, healthcare workers not allocated to ICDM but assisting in service delivery, donated equipment or office supplies), they will be included. Medical and support staff labour costs will be calculated based on the full-time equivalent, duration of involvement in the ICDM model implementation and the gross salary of the personnel.

A proportion of overhead costs of running the health facility like electricity, rent and water will be included in the implementation costs. Administrative costs at district and provincial level (which are beyond the facility) will not be included in the analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Previous research has shown that patients do not like some of the components of the ICDM model26 and that was the basis of the research question. Patients will not be enrolled in the study; however, results will be shared with them through community and health facilities leadership.

Data management and analysis plan

The data will be collected using paper-based questionnaires and later captured into an electronic database. There will be no identifying features (eg, date of birth, addresses) in the database. The health facilities and healthcare workers that participated will be allocated a study number. Source documents will be safely kept and only accessible to study personnel. The data on costs will be manually entered into the CostIt software 200741 according to the provided major categories. CostIt software is a template designed to capture and automatically analyse cost data for different (hospital, PHC and programme) levels of the healthcare system.41

Descriptive statistics (frequency, median, interquartile ranges and percentages) will be used to examine the general quantitative variables of the clinics, such as size, number of chronic patients, services offered, clinic team characteristics and overall functioning status. Following the evaluation, each clinic will receive a score for each of the fidelity criteria items. Item scores will be summed per component to give four overall ICDM component fidelity scores per facility. An overall ICDM model implementation fidelity score will be calculated per facility by summing the four component scores. The implementation fidelity scores will be summarised using descriptive statistics and compared between components, facilities and districts. The outcome of interest will be the degree of implementation fidelity.

The experiences and perceptions of the healthcare workers from the interviews will be analysed with REDCap software for Likert scaled questions and using thematic content analysis for barriers and facilitators of implementation fidelity for qualitative data. The six steps recommended by Braun and Clarke42 for thematic content analysis that will be followed: familiarisation, generating initial codes, searching for themes throughout the database, reviewing and naming themes and summarising the findings.42 Multivariate analysis using STATA V.14 econometric software will be used to assess the effect of various contextual factors on the implementation fidelity of the ICDM model. The impact of both the organisational (case mix, financial flexibility and culture) and implementing team (work experience, cadre of HCW, training and perceptions of ICDM) level factors on the degree of the ICDM model implementation fidelity will be assessed. The initial analysis will include description of the sample, followed by a bivariate analysis that includes t-tests and ANOVA to examine the influence of contextual factors on implementation fidelity of the ICDM model.

Costs: Capital costs and other costs that have a life span of several years will be annualised over the useful life span to get the equivalent annual costs. All costs will be adjusted for inflation and discount. Equipment will be depreciated according to the South African Accounting principles.43 Sensitivity analyses will be conducted for other possible variations in estimated costs. Sensitivity analyses will also be carried out to explore different scenarios including size of clinic, degree of implementation fidelity and other factors that could possibly affect costs based on literature.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical conduct of the study

This study has been approved by the University of Cape Town (Ref: 127/2018) and University of the Witwatersrand (Ref: R14/49) Human Research ethics committees. Approvals have also been received from the Gauteng and the North West Provincial Department of Health. The participants for the interviews will be consented individually prior to taking part in the study.

Dissemination of the results

The results of this study will be shared with the various stakeholders to inform the implementation of the ICDM model in South Africa and other models of integrated care. Brief summary of results will be presented to the provincial and districts departments of health (DOH). The full results will be presented at local research days in each province and district. Facility managers and local clinic staff that participated in the study will be given feedback on the outcomes of the study. The results will also be presented through publications and conference presentations to enhance scientific knowledge. Authorship will be determined by substantial contributions to the study according to the recommendations for the conduct, reporting and publication of research in medical journals. Once the data collection and cleaning are complete, it will be made open and publicly accessible.

Conclusion

Many health systems are challenged with increased demand for healthcare for chronic diseases. Despite this service need, there is minimal integration of services for the management of chronic diseases resulting in inefficiencies in service delivery, high costs and poor health outcomes. The ICDM model has been developed to address this challenge, the success of which will be influenced by the degree to which the model is accurately implemented. This highlights the need for data to assess the degree of fidelity to the ICDM model intervention and for data that explore how fidelity of implementation is affected by contextual factors. Data generated from this study will inform integration of chronic care services at the PHC level and scalability of the ICDM model, of relevance in South Africa and other low-income and middle-income countries increasingly facing a growing tide of chronic disease multimorbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the people that have reviewed this protocol and provided feedback: Leslie London, Edina Sinanovic, Maylene Shung King and South African MRC Self-Initiated Research Grant division.

Footnotes

Contributors: LL was involved in the conception, design literature review and writing. OA, MK and TO have contributed to the conception, design and critical review of the manuscript.

Funding: The proposed study outlined in this protocol will be supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SA MRC) under a Self-Initiated Research Grant (ID:494184). The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SA MRC. The sponsor-appointed reviewers have critically assessed the protocol and requested some changes to be done prior to submission to ethics. The sponsor will have no role in data collection, analysis or reporting.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The protocol has been approved by the University of Cape Town and University of the Witwatersrand Human Research ethics committees. Any changes required, will have to be submitted to both ethics committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

References

- 1. Kim DJ, Westfall AO, Chamot E, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in HIV-infected patients: the role of obesity in chronic disease clustering. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61:600–5. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827303d5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The World Bank. Human Development Network. The growing danger of non-communicable diseases. Acting now to reverse course, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mbanya J, Ramiaya K. Diabetes Mellitus : Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, Jamison DT, Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington DC: World Bank, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vorster HH, Venter CS, Wissing MP, et al. The nutrition and health transition in the North West Province of South Africa: a review of the THUSA study. Publ Health Nutr 2005;8:480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steyn K, Kazenellenbogen JM, Lombard CJ, et al. Urbanization and the risk for chronic diseases of lifestyle in the black population of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa. J Cardiovasc Risk 1997;4:135–42. 10.1097/00043798-199704000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oni T, Unwin N. Why the communicable/non-communicable disease dichotomy is problematic for public health control strategies: implications of multimorbidity for health systems in an era of health transition. Int Health 2015;7:ihv040 10.1093/inthealth/ihv040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertram MY, Jaswal AV, Van Wyk VP, et al. The non-fatal disease burden caused by type 2 diabetes in South Africa, 2009. Glob Health Action 2013;6:19244 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, et al. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e297–e307. 10.3399/bjgp12X636146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prados-Torres A, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Hancco-Saavedra J, et al. Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:254–66. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Statistics South Africa. Mortality and causes of death in South Africa Findings from death notification Statistics South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. UNAIDS. HIV and AIDS estimates. 2015.

- 12. Oni T, Youngblood E, Boulle A, et al. Patterns of HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa- a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:s12879–015. 10.1186/s12879-015-0750-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health Free State. The Free State Department of Health: Annual Performance Plan 2015/2016. 2016.

- 14. Nuño R, Coleman K, Bengoa R, et al. Integrated care for chronic conditions: the contribution of the ICCC Framework. Health Policy 2012;105:55–64. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. Innovative care for chronic conditions: Building Blocks for Action. 2013. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/

- 16. National Department of Health of South Africa. Integrated Chronic Disease Management Manual, A step-by-step guide for implementation. South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci 2013;8:1748–5908. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mahomed OH, Asmall S. Development and implementation of an integrated chronic disease model in South Africa: lessons in the management of change through improving the quality of clinical practice. Int J Integr Care 2015;15 10.5334/ijic.1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gray A, Vawda Y, Padarath A, et al. ; Health Policy and Legislation In: Padarath A, King J RE, eds South African Health Review. Durban, South Africa: Health Systems Trust, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hunter JR CT, Asmall S, Tucker JM, et al. The Ideal Clinic in South Africa: progress and challenges in implementation : Padarath A, Barron P, South Africa Health Review. Durban, South Africa: Health System Trust, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Department of Health. Integrated Clinical Services Management Manual: Republic of South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gabert R, Wollum A, Nyembezi A, et al. The need for integrated chronic care in South Africa: prelimenary lessons from the HealthRise program. 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aantjes C, Quinlan T, Bunders J. Integration of community home based care programmes within national primary health care revitalisation strategies in Ethiopia, Malawi, South-Africa and Zambia: a comparative assessment. Global Health 2014;10:85 10.1186/s12992-014-0085-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maimela E, Van Geertruyden JP, Alberts M, et al. The perceptions and perspectives of patients and health care providers on chronic diseases management in rural South Africa: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:143 10.1186/s12913-015-0812-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. David H, Peters NT, Tran TA. Implementation research in health: a practical guide. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ameh S, Klipstein-Grobusch K, D’Ambruoso L, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated chronic disease management model in improving patients’ CD4 count and blood pressure in a rural South African setting: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahomed OH, Naidoo S, Asmall S, et al. Improving the quality of nurse clinical documentation for chronic patients at primary care clinics: a multifaceted intervention. Curationis 2015;38 10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ameh S, Klipstein-Grobusch K, D’Ambruoso L, et al. Quality of integrated chronic disease care in rural South Africa:User and provider perspective. 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban South Africa, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mahomed OH, Asmall S, Freeman M. An integrated chronic disease management model: a diagonal approach to health system strengthening in South Africa. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:1723–9. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Massyn N, Peer N, Padarath A, et al. District Health Barometer 2014/15. Durban, South Africa: Health Systems Trust, 2014/15. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Day C, Gray A. Health and related indicators. South Africa: Health Systems Trust, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. South Africa, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. International Diabetes Federation. Atlas sixth edition IDF Brussels, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Green HE. Use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research. Nurse Res 2014;21:34–8. 10.7748/nr.21.6.34.e1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. ; Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions. UK MRC: United Kingdom Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidance, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Medical Research Council Guidance: Developing and evaluating complex interventions the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sanson-Fisher RW. Diffusion of innovation theory for clinical change. Med J Aust 2004;180:S55-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rabarison KM, Bish CL, Massoudi MS, et al. Economic Evaluation Enhances Public Health Decision Making. Front Public Health 2015;3:164 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taghreed A, Moses A, David E. World Health Organization [serial on the Internet], 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. South African Revenue Service. Income Tax Act No. 58 of 1962. Binding General Ruling (Income Tax): No. 8, Wear-and-tear or depreciation allowance, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.