Abstract

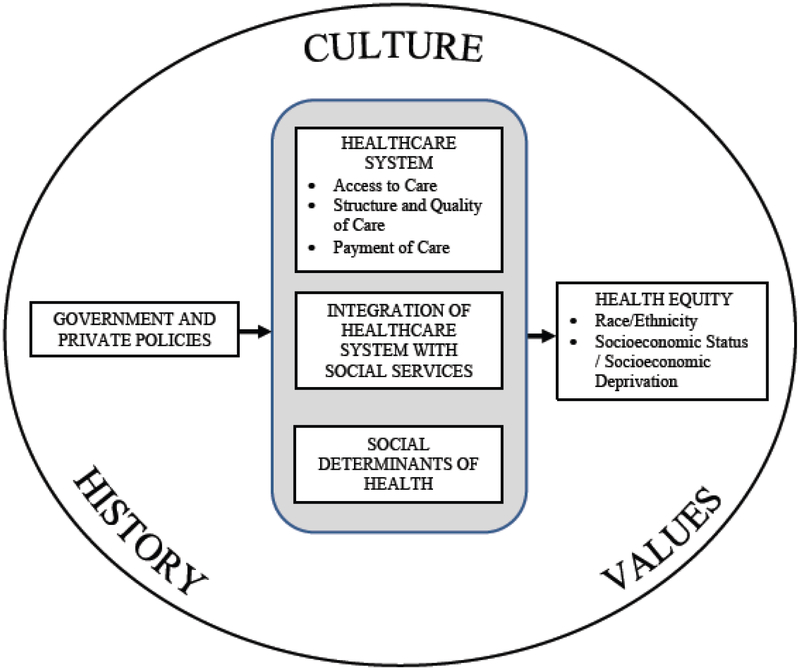

Aotearoa/New Zealand (Aotearoa/NZ) and the United States (U.S.) suffer inequities in health outcomes by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. This paper compares both countries’ approaches to health equity to inform policy efforts. We developed a conceptual model that highlights how government and private policies influence health equity by impacting the healthcare system (access to care, structure and quality of care, payment of care), and integration of healthcare system with social services. These policies are shaped by each country’s culture, history, and values. Aotearoa/NZ and U.S. share strong aspirational goals for health equity in their national health strategy documents. Unfortunately, implemented policies are frequently not explicit in how they address health inequities, and often do not align with evidence-based approaches known to improve equity. To authentically commit to achieving health equity, nations should: 1) Explicitly design quality of care and payment policies to achieve equity, holding the healthcare system accountable through public monitoring and evaluation, and supporting with adequate resources; 2) Address all determinants of health for individuals and communities with coordinated approaches, integrated funding streams, and shared accountability metrics across health and social sectors; 3) Share power authentically with racial/ethnic minorities and promote indigenous peoples’ self-determination; 4) Have free, frank, and fearless discussions about impacts of structural racism, colonialism, and white privilege, ensuring that policies and programmes explicitly address root causes.

Keywords: Equity, Inequity, Access to care, Quality of care, Outcomes, Payment

Introduction

The achievement of health equity remains an important but elusive goal. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that “Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically. Health inequities therefore involve more than inequality with respect to health determinants, access to the resources needed to improve and maintain health or health outcomes. They also entail a failure to avoid or overcome inequalities that infringe on fairness and human rights norms.”1 Braveman and colleagues argue that equity requires the removal of obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, powerlessness, and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and healthcare.2–4 WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health notes the importance of all parts of government and the economy, and the need to coordinate policies to advance health equity.5 Two of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are good health and well-being, and reducing inequalities.6 Specific health targets include universal health coverage, and access to quality healthcare services, medications, and vaccines. Key equity targets are to “ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard.”6

Beyond human rights and social justice, compelling economic arguments support the pursuit of health equity. For example, the societal economic costs of health inequities between Māori and non-Māori children are estimated between $NZ62 million to $NZ200 million,7 and in the United States (U.S.) eliminating racial inequities would have saved over $1 trillion dollars 2003–2006 in direct medical costs, indirect costs such as lost productivity, and costs of premature deaths.8 In addition, absenteeism and presenteeism incur major costs to businesses. Increasingly U.S. companies employ sociodemographically diverse workers and seek health plans that demonstrate they provide high quality care to all patients to enable a healthy workforce.9,10

We compare Aotearoa/New Zealand (Aotearoa/NZ) and U.S. approaches to advance health equity to inform policy efforts. We contrast important drivers of inequities, and mechanisms and tools for solutions. Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S. have many fundamental similarities that increase applicability of lessons. Both countries are western democracies with health systems comprised of publicly and privately funded components, although of differing proportions. The largest racial/ethnic group is of settler European descent, and both countries struggle from colonialism and racism and associated adverse health consequences.11–13 Both countries have broadly implemented neo-liberal policies and structures from the 1980s onwards, leading to increased privatization and a greater emphasis on personal responsibility with a concomitant reduction in state policy, regulation, and funding.14 Neoliberalism may negatively impact social justice, and some have argued that the state must assure equity of opportunity.15 The subsequent rising income inequality has been associated with decreased social capital and cohesion, increased stress, and poorer overall population health.16

Yet, Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S. also have significant population and geographic differences, and fundamental differences in culture, history, and values. As of 2017, Aotearoa/NZ has 4.6 million residents compared to the U.S. population of 326.4 million,17 and Aotearoa/NZ is geographically 34 times smaller than the U.S.18 The largest ethnic minority groups in Aotearoa/NZ are the indigenous Māori (14.9%), Asian (11.8%), and Pacific peoples (7.4%),19 while in the U.S. the largest ethnic minority groups are Hispanic (17.8%), African-American (14.0%), and Asian (6.5%).20 Indigenous American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AIAN) comprise 1.7% and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders 0.4% of the U.S. population.20

This paper will focus on the healthcare system as well as on the integration of the healthcare system with social services.21,22 While numerous important inequities exist across factors such as disability and refugee status, we will focus on race / ethnicity and socioeconomic status / socioeconomic deprivation. Intersectionality, the combination of intersecting systems of oppression that perpetuate discrimination and disadvantage based on factors such as race/ethnicity, class, sex, and gender identity,23 is frequently associated with worse outcomes than any one dimension of disadvantage.24 Systems of discrimination and oppression cannot be completely understood in isolation.25 Therefore, our paper will especially highlight issues for indigenous peoples and racial/ethnic minority population groups as they are more likely to experience disproportionate socioeconomic deprivation.

While multiple ethnic groups in Aotearoa/NZ suffer from important health inequities (Pacific peoples and Asians, among others), we will focus on pervasive Māori:non-Māori inequities because te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi) between Māori and the British Crown in 1840 is the contractual relationship on which Aotearoa/NZ is founded.26 Thus, indigenous rights conferred by the Treaty to monitor government action and inaction around inequities are fundamental to the legal and moral existence and operation of Aotearoa/NZ. We analyze the Aotearoa/NZ system in more detail than the U.S. system because a more extensive literature exists about the latter.

Methods

Conceptual Model

We developed a conceptual model that places policy levers to achieve health equity within cultural and historical contexts, building upon more detailed equity models and literature (Figure 1).3,5,27 Our model identifies that health equity among more and less advantaged groups is affected by the healthcare system and fundamental social factors, including housing, education, employment, poverty, food insecurity, and the criminal justice system. Government and private policies that impact the healthcare system (access to care, structure and quality of care, and payment of care), social determinants of health, and the integration of the healthcare system with social services, are critical determinants of health equity. These policies are created in a political environment highly influenced by a country’s underlying cultural and historical contexts, and predominant values.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Key Policies and Contexts Impacting Health Equity

We performed a narrative literature overview based on a broad and deep environmental scan of the components of the conceptual model,28–30 drawing upon health care, sociological, and historical literature. We analyzed and categorized this information by components of the model, and came to consensus on the objective descriptions of each nation’s health systems and interpretation of their strengths and weaknesses. Health equity experts from both nations reviewed our paper. We discussed their feedback and incorporated those points that we believed were valid.

Results

Health Inequities in Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States

A large empirical literature in both countries documents significant health inequities across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status for mortality, morbidity, quality of care, and patient experience.13,31–35 In Aotearoa/NZ, life expectancy at birth is 75.1 years for Māori, and 82.1 years for non-Māori, a gap of 7.0 years.33 When comparing least socioeconomically deprived to most deprived areas, life expectancy at birth was greater by 7.5 years in males and 6.1 years in females.36 In 2013, over half of the entire Māori population (63.4%) lived in the most socioeconomically deprived deciles (7–10).31 In 2008 in the U.S., white men with 16 years or more of education lived 14.2 years longer than black men with fewer than 12 years of education.37 In the Commonwealth Fund’s 2017 international rankings of health equity in 11 Western countries, Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S. rank 8 and 11, respectively; 11 being the worst ranking.38

Causes of Health Inequities in the Context of History, Culture, and Values

Social determinants of health, including social and physical environments,39 and factors such as income, education, social cohesion, and neighborhood quality, explain most of the inequities in population health outcomes in both Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S., with healthcare estimated to account for approximately 10% of the variation.40 Colonialism, characterized by historical and contemporary dispossession, subjugation and forced assimilation, has disrupted Māori culture and sovereignty with longterm deleterious effects similar to the experience of indigenous populations in the U.S. and globally.41,42

Racial/ethnic minorities in both countries face bias and institutional and personally mediated racism with associated serious health consequences.43–45 Legalized racism manifested itself in the persecution, marginalization, and alienation of indigenous populations,46 the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras in the U.S.,47 anti-Asian immigration laws,48,49 and discriminatory approaches to Latinos in the U.S. criminal justice and immigration systems.50 The devastating effects of colonization continue to have adverse impacts on American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders in the United States,51 as well as for Māori in Aotearoa/NZ. Over 50 pieces of Aotearoa/NZ legislation affecting sovereignty, land ownership, franchise, voting and culture have discriminated against Māori, for example the 1862 and 1865 Native Land Acts which allowed settlers to acquire Māori land without consent from Iwi (nations).52–54 These examples highlight the structural racism that impact health through mechanisms such as substandard housing, education, employment, health care, and economic opportunity.

Both countries share numerous barriers to access and high quality care including low health literacy,55,56 limited cultural competence of providers, lack of transport, and inadequate childcare.13 Out-of-pocket costs are significant barriers to access to care. Co-payments to general practitioners (GPs) in Aotearoa/NZ are unaffordable to some and the uninsured in the U.S. often rely on charity care. Although a greater proportion of health funding is from government’s public funding in Aotearoa/NZ compared to the US, a two-tiered health system also exists in Aotearoa/NZ. The two-tiered system means the wealthier, and those who purchase private insurance packages (approximately one-third of the population), can gain access to diagnostic tests and surgical and medical procedures more quickly through the private sector than those who are solely reliant on the publicly-funded health sector.57

Queue-jumping by the wealthy for earlier diagnosis may be an explanation for differences in patterns of hospital presentation for bowel cancer in Aotearoa/NZ. Of patients with colon cancer, 43% of people in the lowest (poorest) socioeconomic Aotearoa/NZ Deprivation (NZDep) quintile had their initial disease presentation at an emergency department, as opposed to within primary care, compared to 29% in the highest quintile.58 Forty-four percent of Māori and 51% of Pacific people diagnosed with colon cancer presented as an acute emergency, compared with 33% of non-Māori-non-Pacific people.58 Among patients with cardiovascular disease, preventable deaths have occurred from lack of access to life-saving cardiac interventions and surgery.59,60

Similarly, in the U.S., the uninsured and those with Medicaid insurance often have more difficulty accessing specialists and mental health providers, for reasons including a limited number of providers who will see these patients.61 Delays in accessing primary and specialty care have adverse health consequences, including presenting with advanced stage cancer and having worse survival for some cancers.62,63

In contrast, important historical, cultural, and geographic differences exist between Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S. that impact the nature of health inequities.64 For example, the legacy of slavery in the U.S.,65 and the history of Hispanic/Latino colonization of and migration to the U.S. have complicated contexts with no direct parallel in Aotearoa/NZ.66 Māori represent a greater percentage of the nation’s population than American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and appear more visible politically with seven Māori electorates that reserve positions to representatives of Māori in the Aotearoa/NZ Parliament.19,67 There is also an ongoing history of independent Māori political party action.68

The Treaty of Waitangi is purported to play a critical role in Aotearoa/NZ’s history and culture. The Treaty is said to have formed the foundation of a contractual relationship between two internationally recognised sovereign nations – Māori, as tāngata whenua (people of the land) of Aotearoa/NZ, and the British Crown. The Treaty document is prominently displayed in national museums and commonly evoked in discussions around equity. However, it has a contentious history with significant differences in the Māori and English translations, and the Treaty was not formally recognized, or upheld, by many successive governments. Only the Māori version has consistently been recognised by Māori since 1840. This was the version that over five hundred Rangatira (chiefs) as representatives of their Iwi (nations) viewed, discussed and signed with British Crown signatories at Waitangi on February 6, 1840.69 The English version of the Treaty decrees the ceding of Māori sovereignty to the Crown. In contrast, the Māori version has no mention of this whatsoever. Māori political figures over the years, current legal experts and the Waitangi Tribunal (the Crown-introduced and determined mechanism by which Treaty grievances are investigated) all assert that Māori did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown in 1840.52,70,71

Post-Treaty Aotearoa/NZ underwent a period of wars and land confiscation similar to that experienced by American Indians. However, as a result of Māori sovereignty movements that have focused on Treaty rights, there has been some national responsibility at least since the mid-1970s to honor Māori protections in the Treaty.26 From American historical and ethical perspectives regarding racial and ethnic minority populations, the Aotearoa/NZ experience resonates in different ways from broken U.S. governmental treaties with American Indians and the emphasis on individual rights in the American Civil Rights Act of 1964.46,72 For example, in his 1963 speech “Report to the American People on Civil Rights,” rather than stressing legal obligations, President John F. Kennedy stated: “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.”72 Discussing the right of African Americans to be served in a public restaurant, he declared “This seems to me to be an elementary right. Its denial is an arbitrary indignity that no American in 1963 should have to endure, but many do.”72

Aspirations Reflected in the National Health Strategies

Both countries share strong aspirations for health equity in their national health strategy documents that provide high-level frameworks and guidance for achieving health equity (Table 1).73–78

Table 1.

Aotearoa/New Zealand and United States

| National Health Visions and Selected Equity Plans |

| I. Aotearoa/New Zealand |

| A. National Health Strategy and Roadmap73 |

| 1. Aim: a future health system in which “All New Zealanders live well, stay well, get well, in a system that is people-powered, provides services closer to home, is designed for value and high performance, and works as one team in a smart system.” |

| 2. Eight guiding principles for the system (italics added for emphasis of equity goals and cross-sector collaborations): |

|

| B. The Guide to He Korowai Oranga Maori Health Strategy 201476 |

| Overarching aim - Pae ora - healthy futures |

| 1. 3 Elements |

|

| 2. Directions |

|

| 3. Key threads |

|

| 4. Pathways for action |

|

| 5. Strengthening He Korowai Oranga |

|

| C. Equity of Healthcare for Maori - A Framework75 |

| 1. Leadership - championing the provision of high-quality healthcare that delivers equity of health outcomes for Māori |

|

| 2. Knowledge - developing knowledge about ways to effectively deliver and monitor high-quality healthcare for Māori |

|

| 3. Commitment - being committed to providing high-quality healthcare that meets the healthcare needs and aspirations of Māori |

|

| II. United States |

| A. Healthy People 2020 vision statement74 |

| 1. Aim: “A society in which all people live long, healthy lives” |

| 2. Mission (italics added for emphasis of equity goals and cross-sector collaborations): |

|

| 3. Overarching goals: |

|

| B. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities77 |

| 1. Transform healthcare |

|

| 2. Strengthen the nation’s health and human services infrastructure and workforce |

|

| 3. Advance the health, safety, and well-being of the American people |

|

| 4. Advance scientific knowledge and innovation |

|

| 5. Increase efficiency, transparency, and accountability of HHS programs |

| C. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Equity Plan for Improving Quality in Medicare78 |

| 1. Expand the collection, reporting, and analysis of standardized data |

| 2. Evaluate disparities impacts and integrate equity solutions across CMS programs |

| 3. Develop and disseminate promising approaches to reduce health disparities |

|

| 4. Increase the ability of the healthcare workforce to meet the needs of vulnerable populations |

|

| 5. Improve communication and language access for individuals with limited English proficiency and persons with disabilities |

| 6. Increase physical accessibility of healthcare facilities |

Actual National Policies, Regulations, and Incentives Affecting Health Equity for Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States

Tables 2–5 list key national policies affecting health equity for access to care; integration of healthcare system with social services; structure and quality of care, and payment.79,80 Overall, both countries have relatively few strong policies with support, incentives, and enforcement that are explicitly designed to achieve equity for racial/ethnic minority and socioeconomically deprived populations. In Aotearoa/NZ, District Health Boards (DHBs), legislated government-funded regional health organisations with responsibility for providing, planning and purchasing 80% of Aotearoa/NZ’s healthcare services, have statutory obligations to Māori to improve health outcomes and reduce inequities with a view to eliminating them. However, in 2012, the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) found that “the combination of lack of information in the annual reports on Māori health needs and on targets to reduce disparities makes it hard to gauge DHBs’ progress.”81 The OAG revisited the issue in 2014 finding that performance had improved, but that several areas of concern remained, noting “several DHBs still needed to provide better information about the extent of disparities for their Māori population, the initiatives and programmes to reduce disparities, and the progress that has been made in reducing those disparities.”82

Table 2.

National Health Policies Addressing Access to Care

| A. General policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| Public system: 80% of total health expenditures86 All citizens and permanent residents can access publicly funded health and disability services for preventive, inpatient and outpatient hospital services, primary care, prescription drugs in national formulary, mental healthcare, dental care for schoolchildren, home support services and long-term residential care for older adults, hospice, and disability support Out-of-pocket payment Co-payments for general practitioners (GPs) and nursing services in GP clinics Co-payments for first 20 prescriptions per family per year ($NZ5.00 per item) Primary care 13 years and under - free Others - 98% are subsidized in Primary Health Organisations (PHO) National requirements for publicly funded services for the 20 District Health Boards (DHBs) Annual budget and benefit package determined by political priorities and health needs Rationing and prioritization for nonurgent services Privately funded - 20% of total health expenditures Out-of-pocket payment - 12.6% of total health expenditures79 Private insurance Levies for no-fault injury compensation scheme Private insurance - 35% of all adults, fewer Māori and Pacific adults (adjusted rate ratios 0.5 and 0.6, respectively); 28% of all children age 0–14 years, fewer Māori and Pacific children (adjusted rate ratios 0.4 and 0.5, respectively)180 5% of total health expenditures Cost-sharing Elective surgery in private hospitals Private outpatient specialist consultations Faster access to nonurgent treatment |

Public insurance - Approximately 50% of total health expenditures;181 37% of residents80 Medicare (65 yrs and older; end-stage renal disease) - 16% Medicaid (poor, disabled) - 20% Direct purchase - 16% Military - 4.7% Privately funded - Approximately 50% of total health expenditures Private voluntary health insurance, mostly employer-based - 67% of residents 2016 – 8.6% uninsured 2010 Affordable Care Act182 Medicaid expansion determined by states (33 states and District of Columbia have expanded) 90% subsidy by federal government Insurance exchanges for those not qualifying for Medicaid- subsidized premiums Individual mandate - requirement to buy health insurance (repealed in 2017) 10 essential health benefits coverage required (e.g. ambulatory / outpatient services; emergency services; hospitalization; pregnancy, maternity, and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; pediatric services, including oral and vision care.) Insurance variables Co-payments Deductibles High-deductible health plans; health savings accounts Tiered drug prescription formularies - Differential pricing of generic and brand-name drugs Value-based insurance design Better coverage of more effective treatments Federal and state workmen’s compensation laws Tort system for injuries |

| No fault Accident Compensation Corporation: Universal coverage for acciental injuries including treatment costs and 80% of pre-injury earnings |

|

| B. Equity-specific policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| Patient co-payments capped ($NZ17.50) in low-income areas (1/3 Aotearoa/NZ) | Federally-qualified health centers Public hospitals Local health departments Free clinics Disproportionate share hospital payments for uncompensated care Charity care - private providers |

Table 5.

National Health Policies Addressing Payment

| A. General policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| Primary care General practitioners (GP) ½ income government subsidy paid thru Primary Health Organisations (PHOs) + patient copayments Pay-for-performance PHOs - additional per-capita funding to improve access Multidisciplinary care teams Pay-for-performance - 3% additional - cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease screening and follow-up, vaccinations. Outpatient specialists Salary - District Health Board (DHB), public hospital Private practice and private hospital - Fee-for-service; set own fees |

Gradual transition from fee-for-service to value- based purchasing Fee-for-service: pay for volume Value-based purchasing: pay for quality Aiming for 90% of Medicare payment by 2018 Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Reauthorization Act (MACRA) Merit-based Payment Incentive System (MIPS) - Fee-for-service payment linked to clinical performance incentives - 90% of FFS payments by 2018 Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs) - 50% of Medicarepayments by 2018 - e.g. global and capitated payments, patient-centered medical homes (PCMH), accountable care organizations (ACO) |

| Mental healthcare - mostly public | Mental healthcare - private and public |

| Home support services for older adults- DHBs | Long-term care - Medicaid, private insurance, selfpay |

| Residential care for older adults - means-tested public subsidy, self-pay | |

| Pay-for-performance in Medicare program Hospital Readmissions Reduction Hospital-acquired Conditions Reduction Hospital Value-based Purchasing Medicare Advantage Star Rating Medicare Shared Savings Physician Value-based Payment Modifier End-stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Skilled Nursing Facilities Home Health Agencies |

|

| Medications Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand (PHARMAC) creates evidence-based national drug formulary with criteria including cost-effectiveness analyses. PHARMAC lowers drug prices by negotiating with pharmaceutical companies. |

Medications United States Veterans Administration negotiates drug prices with pharmaceutical companies Medicare and Medicaid programs are forbidden from negotiating with pharmaceutical companies |

| B. Equity-specific policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| National Population-based Funding Formula for health services to DHBs adjusted by New Zealand Index of Deprivation, ethnicity (Māori , Pacific Islander, Other), sex, and age Very Low Cost Access (VLCA) funding for practices with 50% or more of patients registered as high need based on bottom quartile social deprivation, Māori, Pacific peoples |

Selected case-mix adjustment in some funding Inconsistent use of some social risk factor data in some of Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Programs Increase payment for dual-eligible (patients with Medicare and Medicaid insurance) in Medicare Advantage Program Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments for uncompensated care Social risk factor adjustment trial period in performance measure reporting for Medicare and Medicaid |

In addition, even though both countries have several equity-specific policies, the safety net is consistently underfunded and underresourced. For example, in 2012 the city of Chicago closed half of its mental health clinics for what patient advocates presumed to be budgetary reasons. Incarceration rates increased and now the Cook County Jail is one of the largest providers of mental health services in the U.S. at great expense to taxpayers.83

Access to Care

Aotearoa/NZ has a stronger safety net for access to care for citizens and permanent residents than the U.S., with publicly funded health and disability services for preventive, inpatient, outpatient, primary care, prescription drugs, mental healthcare, dental care for children, home support services and long-term residential care for older adults, and disability support (Table 2).84,85 Co-pays are generally required, but the proportion of the Aotearoa/NZ health expenditure that is private is approximately 20% (including levies to fund a national no-fault injury compensation scheme); about 80% being publicly funded.86 Attempts in the U.S. to expand insurance coverage such as through the Affordable Care Act still fall far short of Aotearoa/NZ’s floor coverage for residents.87 However, compared to the U.S., the national healthcare budget in Aotearoa/NZ determined through the political process imposes a stricter cap on spending, which limits access through rationing and queuing for nonurgent services,57,88,89 and sometimes for urgent services.59 New Zealanders with private insurance, and the wealthy, can largely bypass these queues. Migrant populations, including refugees, in both countries have limited eligibility for services.84

Access to injury-related care and resources differs substantially across the two countries. The universal no fault Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) in Aotearoa/NZ provides universal coverage for injuries including treatment costs for all residents and visitors to Aotearoa/NZ, and up to 80% of pre-injury earnings to Aotearoa/NZ residents.57,90 ACC was introduced in the early 1970s to address inequities and perverse incentives associated with the previous litigious system for injury-related compensation. Despite ACC’s universal entitlement, however, Māori experience inequities in access and outcomes.91 The U.S. relies upon a patchwork set of less comprehensive federal and state workmen’s compensation laws that vary substantially in coverage.92 Victims of medical malpractice can sue for damages, but the tort system is inefficient. Only 2 percent of negligent injuries result in claims, and administrative expenses comprise 60% of total system costs.93

Funding formulae impact the allocation of resources and access to care. Aotearoa/NZ explicitly adjusts for socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity in its national population-based funding formula for budgetary allocations to DHBs. Whilst it adjusts using the New Zealand Index of Deprivation (NZDep) which includes internet access, income, employment, education, home ownership, social support, living space, and access to a car,94,95 ethnicity (Māori, Pacific peoples, Other), rurality, and sex, the adjustment for age has the greatest impact through redistribution of resources to those ethnic groups with older population age structures (NZ European).

Primary care is funded by a combination of government capitation contributions (per enrolled patient), and fee-for-service (FFS). About 30% of primary care practices in Aotearoa/NZ use the Very Low Cost Access (VLCA) funding that began in 2006. VLCA funding provides a higher level of government subsidy to practices which agree to limit patient co-payments for general practice consultations. The original intent was to provide an alternate funding model for practices, in particular to support those serving communities with lesser ability to pay out of pocket. Subsequently this funding model was limited to practices with more than 50% “high needs” patients (most socioeconomically deprived quintile, Māori, Pacific peoples).96

Issues around equitable access persist however. For example, about 500,000 “high needs” patients throughout Aotearoa/NZ are not enrolled in a VLCA practice,97 and similar numbers of non-“high needs” patients are enrolled with VLCA practices. Patient age has the most significant impact on the quantum of government capitation contributions, such that any additional funding for VLCA practices is likely to be offset by the younger age profile of “high needs” population groups.

Racial/ethnic minority physicians are more likely to serve disadvantaged populations than majority physicians.98,99 Workforce development programs have significantly increased the number of Māori and Pacific peoples in medical schools in Aotearoa/NZ and provided support and training to facilitate student success.100 Political and legal debates over affirmative action have slowed efforts to increase the numbers of underrepresented minority physicians in the U.S.101

Integration of Healthcare System with Social Services

Aotearoa/NZ policies more explicitly address social determinants of health than the U.S,102 although integrated medical-social services are often at the model program stage, the quality of implementation has varied, and results are mixed (Table 3). Aotearoa/NZ’s greater ratio of spending on social services as opposed to healthcare leads to greater focus on social determinants of health.103 Post-2008, Aotearoa/NZ’s Whānau Ora policy has aimed to give more control to whānau (extended family) and have services designed around their needs and aspirations. This has driven integration of some health and social services and encouraged joint accountability for outcomes.104

Table 3.

National Health Policies Addressing Integration of Healthcare System with Social Services

| A. General policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| Programs integrating health and social services 2017- Social Investment Agency - data analytics, risk stratification of population, targeted interventions to reduce costs and improve outcomes | Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), global budgets, capitation, bundled payment, shared savings plans - indirect incentives for integration and coordination |

| B. Equity-specific policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| 2000s - Multisector policy - housing, education, health District Health Boards (DHBs) and Primary Health Organisations (PHOs) required to develop strategies to reduce disparities PHOs created specifically for Māori or Pacific populations Post-2008 - specific policies Whānau Ora - integrate health and social services Develop coordinated, multiagency approaches to service provision and foster joint responsibility for outcomes Cross-sector trials for teenagers - truancy, crime; alcohol and drug abuse; education, training, or employment |

Accountable Health Communities - link persons with health-related social needs to community resources along with funding stream State Innovation Model (SIM) - some states such as Minnesota integrate medical and social services Integration of medical and social services for older Medicaid beneficiaries who need long-term care |

The Aotearoa/NZ Social Investment Agency is a cross-agency unit that focuses on valuedriven investments.105 The Agency uses integrated administrative datasets of variable quality and coverage to determine population needs and provide feedback on the fiscal implications of investing or not. The Social Investment Agency has been very controversial. Supporters suggest that predictive risk modelling could streamline helpful services to individuals. Critics note the high risks of reinforcing cognitive and structural biases,106 and that formulae emphasize cost savings rather than societal benefits.107 Subsequent policies could be viewed as punitive, potentially harmful, and stigmatizing to individuals. Analyses are limited by the available data and thus might not target services to the groups who need them most.107 Privacy is invaded and it might be dangerous for the state to have these detailed data.

Commentators highlight that if the goal is to improve health equity and avoid negative unintended consequences, effective tools and analytical techniques must be embedded within a culture that truly prioritizes improving individuals’ well-being ahead of cutting public spending. Potential safeguards for predictive analytics include developing a code of ethics, making transparent the data analysis process and use of results, assessing impact on equity, and analyzing not only individuals but also neighborhoods to examine which areas need more resources.106

In the U.S., early model accountable care organizations (ACOs) that cover more than 10% of the population create implicit incentives to address social determinants to keep people healthy and prevent costly health expenditures.108,109 These incentives are most explicitly designed in the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) Accountable Health Communities initiative which requires screening for health-related social needs and linkage of persons to community resources that can address those needs, and creates funding streams to support integrated, cross-sector efforts.110 In the CMS State Innovation Model, states implement multipayer healthcare payment and delivery system reform programs.111 Some grantees have integrated medical and social services such as Minnesota’s Accountable Communities for Health.112

Overall, both countries struggle with collaboration across sectors including health, housing, education, employment, urban planning, and public safety. Challenges include creating shared governance and funding streams across sectors, and developing, implementing, and rewarding joint accountability metrics for the common good of the population.

Both countries also struggle to address the inequitably distributed public health impacts of harmful commodities (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, problem gambling, firearms) that have significant corporate influences.113 For instance, the tobacco industry has targeted and tailored their advertising and outreach to the African-American community.114 Anti-smoking strategies have lowered smoking rates in both countries, but ethnic inequities remain.115,116 The focus on individual behavior change rather than population-level approaches reducing supply and demand (e.g., increasing price and taxes; reducing access, advertising, and sale of products) appears to have worsened inequities. Disappointingly, despite strong population-based recommendations in the Aotearoa/NZ Law Commissions report on reducing alcohol-related harm, few have been implemented,117 and the U.S. has made little progress enacting sensible gun control regulation or funding gun violence research.118

Structure and Quality of Care, and Payment

The U.S. has small independent physician and group practices as well as larger managed care plans and integrated delivery systems. Health inequities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status are seen across different practice arrangements,119,120 involving tensions between cost control and quality of care, and access to care (such as which providers are covered by managed care plans and preferred provider networks that selectively contract with providers). Both for-profit and non-profit, and public and private providers and hospitals exist, with organizational characteristics associated with inequities and cultural competence.121,122 A perenially underfunded Indian Health Service provides care to 2.2 million AIAN.123 Many Aotearoa/NZ physicians divide their work between public and private systems, exacerbating inequities if they favor private patients.57 Compared to commercially owned primary care clinics, community-governed practices in Aotearoa/NZ care for more patients from lower socioeconomic groups and charge lower fees.124

Value-based purchasing systems that reward quality of care are increasing in both countries (Tables 4 and 5). In the United States, federal value-based purchasing programs cover inpatient, physician, managed healthcare plan, and end-stage renal disease care. By 2018, the U.S. Medicare program aims to have 90% of its fee-for-service payments tied to value in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System.125 However, payments to physicians will only be adjusted +/−4% in 2019 increasing to +/− 9% in 2022.126 In Aotearoa/NZ, 3% of primary care payments are subject to pay-for-performance.79 Incentivizing improvement in quality of care and outcomes for the aggregate patient population theoretically provides an indirect incentive to improve care of patient groups that are doing poorly. In practice, however, inequities in both countries have largely persisted, suggesting that generic “rising tide lifts all boats” policies for improving quality of care are flawed for achieving equity.127

Table 4.

National Health Policies Addressing Structure and Quality of Care

| A. General policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| Structure of care: | Structure of care: |

| 20 District Health Boards (DHBs) Plan health services and seek to achieve government objectives Operate government-owned hospitals and health centers Provide community services Purchase services from nongovernment and private providers Primary Health Organisations (PHO) – self-employed providers Most general practitioners (GPs) belong to organized networks Many specialists work independently in multispecialty clinics District-level alliances (DHBs, PHOs and others such as pharmacy, ambulance, district nursing, allied health, local government, Māori providers) to drive stronger system integration by changing service models. |

Small independent physician and group practices Managed care plans and integrated delivery systems Capitation Preferred provider networks - selective contracting of providers with health plans Which providers are available in Medicaid plans and low-cost plans Population health management For-profit, non-profit, public |

| Public reporting of performance data: Health Quality and Safety Commission - Atlas of Healthcare Variation District Health Boards Six health targets Waiting times Access to primary care Mental health outcomes Primary Health Organisations Screening rates for chronic disease Annual Quality Accounts by DHBs since 2012 Public hospitals Patient experience surveys |

Public reporting of clinical performance data in Medicare program: Hospital Compare Physician Compare Nursing Home Compare Home Health Compare |

| B. Equity-specific policies | |

| Aotearoa/New Zealand | United States |

| The New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000, section 22(1)(e) and (f) states that DHBs must work to reduce health disparities by improving health outcomes for Maori and other population groups. Stratified data public reporting at early stages - Māori, Pacific peoples, NZ European and Asian Workforce development - Māori, Pacific peoples affirmative action for medical schools Medical Council of New Zealand cultural competency training requirements and indigenous standards Very Low Cost Access (VLCA) practice Māori and non-governmental organization (NGO) versions could have community health workers / patient navigators, well-child programs, longterm condition programs, colocated services, function as team, mobile stations Māori health programs Equity research funding e.g. causes of inequities and solutions |

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Equity Plan for Improving Quality in Medicare (see Table 1) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (see Table 1) Stratified data public reporting at early stages at CMS - aggregate national statistics Workforce development - No affirmative action for medical schools Undergraduate Medical Education and Graduate Medical Education cultural competency training largely voluntary Indian Health Service: Hospitals, clinics, health stations Underfunded Facilities managed by Indian Health Service, tribes, urban health stations Equity research funding - e.g. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and specific health disparity program announcements and requests for applications from other National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutes |

Aotearoa/NZ is recognized internationally for its quality of ethnicity data in health datasets, critical for measuring and reporting inequities in quality of care across ethnic groups. Indigenous health leaders have advocated for high quality ethnicity data over many years, ensuring visibility for all ethnic minority groups. However, both countries are at early stages of publicly reporting standardized national clinical performance data stratified by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation.128,129 The DHB Māori Health Profiles present key health indicators for Māori compared with non-Māori. Summary profiles are provided in te reo Māori (the Māori language). Both Aotearoa/NZ’s Health Quality and Safety Commission’s Equity Explorer and the Trendly database (www.trendly.co.nz) provide limited data on performance indicators for Māori, though of the two, Trendly is the most up to date.130 Aotearoa/NZ does not routinely publicly report national performance measures which are reflective of public and government priorities (e.g. National Health Targets), by ethnicity or deprivation – but instead uses the total population indicator.131 The United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Healthcare Quality and Disparity Reports note persistent disparities in processes of care and outcomes across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.127

Both countries lack high quality data on Asian, Pacific peoples, and other ethnic subgroups. Also, frequently aggregating these subgroups or combining them with “Other” ethnicities, has led to invisibility and lack of prioritizing health needs of these groups. Important distinctions are lost such as countries of origin, whether native-born or not, and refugee status.

Neither country explicitly rewards reduction of healthcare inequities. Until a recent trial period, the U.S. Medicare program forbade adjustment of clinical performance measures for social risk factors.132 In Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Programs, crude social risk factor data such as whether a patient has Medicaid insurance is applied to specific programs,133 but not through a systematically developed approach such as the NZDep which is sensitive to small area variation in socioeconomic deprivation.94

The National Academy of Medicine, U.S Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, and National Quality Forum (NQF) all recommend social risk factor adjustment for payment and/or public reporting of performance measures under specific circumstances.133–135 They note that incorporation of an equity lens into quality improvement and payment efforts is a potentially high-yield opportunity.136

The governmental Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand creates an evidence-based national drug formulary using cost-effectiveness analyses, and lowers drug prices by negotiating with pharmaceutical companies.137 The U.S. Veterans Administration that cares for former military personnel negotiates drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, but the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are forbidden from doing this negotiation.138 Thus, medication prices are lower in Aotearoa/NZ than the U.S., and the high costs of medications contribute to health inequities in the U.S.

In Aotearoa/NZ cultural competence, embedded in legislation under the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act,139 is incorporated in health professional education and training programs. However, the extent to which trainees and graduates are required to demonstrate competence in Māori health and health equity is limited. In the U.S., cultural competency training at the Undergraduate Medical Education and Graduate Medical Education levels has been voluntary although expanding.140

Equity Roadmaps and Promising Demonstration Programs

Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the key evidence-based processes and practices from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers Program (www.solvingdisparities.org) and National Academy of Medicine.27,141 Key principles include commitment to achieving equity, implementing a data-driven quality improvement process with root cause analysis that addresses the patients’ specific needs in context, and forming partnerships with families and communities. Team-based approaches incorporating community health workers have been effective. Successful programs tackle issues at multiple levels, such as the patient, clinician, organization, community, and policy, and address medical and social determinants of health. Sustainability requires institutionalization and healthcare payment policies that explicitly support equity. Promising demonstration programs have followed these principles for success.

Aotearoa/NZ Childhood Immunization

Between 2007 and 2012, the Aotearoa/NZ Ministry of Health set immunization targets for two-year old children, starting at 80% for July 2009 and increasing to 95% by July 2012.142,143 In 2007, immunization rates were 74% for non-Māori-non-Pacific children and 59% for Māori. By June 2012, the gaps had largely disappeared; rates for NZ European children were 93% vs. 92% for Māori.142 Accountability was critical. The Minister of Health set the expectation with a directive that the target be achieved for all population groups including Māori, Pacific peoples, and those living in the most deprived households. The Ministry of Health then published quarterly public reports of immunization rates ranking DHBs. This new system established accountability from the nation to DHBs to primary health organisations to primary care providers and local champions.

Collaborative and competitive improvement techniques were incorporated.142 Immunization networks comprised of DHBs within regions shared best practices as did immunization advisory groups within DHBs. Public rankings created comparative competition. Other contributors to success were teamwork, improved communication and coordination of activities across partners, and passion. Systems processes included funding for immunization, outreach to families with better follow-up, immunization with community based organizations, data systems for tracking and monitoring, pay for performance, and lay advocates.142

Māori Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI) Prevention

Sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) is the leading cause of preventable death for babies in Aotearoa/NZ. Though Aotearoa/NZ has made progress in significantly reducing rates of SUDI over the last two decades with universal safe sleep messaging that focused on downstream risk factors, such interventions were far less effective for Māori.144 Currently, though still higher in Māori compared with non-Māori, rates are improving for Māori babies secondary to culturally tailored interventions developed by indigenous leaders.144 Māori women have higher rates of maternal smoking and bed sharing with their babies than NZ European women, both associated with higher rates of SUDI. A randomized trial of the wahakura (traditional flax woven basket) versus the gold standard bassinet found that the subsequent rates of infant risk behaviors in each group were similar, supporting comparable effectiveness of each sleeping device in preventing SUDI,145 and there were additional advantages with the wahakura such as sustained breast feeding. Some Māori women may be more likely to effectively use the wahakura than the standard bassinet, especially when embedded within a cultural tailored intervention. In the Te Aka Oranga Waikawa Wahakura Wananga programme,144 master flax weavers create wahakura and teach mothers about safe sleeping practices, decreased smoking, and breastfeeding. Mothers in that programme reported holistic spiritual educational experiences, more engagement, and increased use of wahakura.144 Aotearoa/NZ is now developing a national SUDI prevention programme with universal and culturally tailored approaches.

Nuka System of Care for Alaska Native People in Anchorage, Alaska

The Nuka System of Care is a holistic, population-based healthcare system owned, created, and implemented by Alaska Native people to maximize physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being.146 Alaska Native people took control of their healthcare system from the federal Indian Health Service and became customer-owners who tailored the system to meet their needs through a self-determined process. Key principles were shared responsibility, commitment to quality and continuous improvement, and family wellness. Care is mostly prepaid, in Anchorage and rural areas with outreach, using a tailored patient-centered medical home. Relationships are critical, with patients and across the organization. The system has improved access to care and quality of care; reduced emergency department visits, specialty visits, and hospital days; reduced staff turnover; and had high patient satisfaction.146 The Nuka System of Care demonstrates that health inequities are not inevitable when self-determination is enabled. In contrast, Māori providers face a variety of institutional challenges around self-determination and autonomy, rigid non-Māori world views of health care systems, funding, and power that have made creation of a system analogous to Nuka unachievable to date in Aotearoa/NZ.147

Minnesota’s Hennepin Health Safety-Net Accountable Care Organization

Hennepin Health is an ACO that cares for 8700 high-risk, low-income patients in Minnesota’s Medicaid program.148 Approximately 70% come from racial/ethnic minority groups, and of those who sought care in the first 18 months of the program 60% had a major psychiatric diagnosis.149 Sixty-five percent report lack of social support, 43% housing needs, and 24% alcohol or drug use concerns.149 Four county health organizations partner with the Minnesota Department of Human Services to provide medical and social services for these patients. The Medicaid program pays the ACO a per-member per-month fee, and any savings or losses are shared by the partners. An integrated electronic medical record and data warehouse risk stratify patients to identify those most likely to benefit from intensive case management. Community health workers and a care coordination team facilitate health and social services. Early results show an increase in outpatient visits, decrease in emergency department visits and hospitalizations, increased quality of care, and high patient satisfaction with their experiences.148 The global capitated budget allows the ACO to invest upfront in community health workers, care coordination team, and data infrastructure.

Discussion

Analysis of Aotearoa/NZ and U.S. approaches to advance health equity yield important lessons. Nations must authentically commit to achieving health equity. For Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S., a chasm exists between national aspirational goals for health equity and persistent health inequities in quality of care and outcomes. Inequities across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status after decades of Māori health, ethnic minority health, and care of socioeconomically deprived groups being declared “priorities” is evidence that, despite the rhetoric, our societies are disturbingly tolerant of these inequitable health outcomes.150

Lessons for Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States

Several key actions could significantly advance equity: 1. Explicitly design quality of care and payment policies to achieve equity, holding the healthcare system accountable through public monitoring and evaluation, and supporting with adequate resources.151 National equity statements are ineffective if implementation practices are not specifically geared to achieve equity. National quality improvement and payment efforts have not been designed with explicit goals of supporting and incentivizing health equity.152 Existing programs are not supported by accountability mechanisms based on outcomes and achievement of health equity. Payment policies must align with health equity to enable sustainable equity interventions to occur and to help motivate constructive action by healthcare organizations, clinicians, and administrators.9 Also, both countries have focused their health payment systems, budgeting, and attention mostly on acute hospital and specialty care rather than preventive and primary care services that are critical for prevention, early diagnosis and treatment to reduce complications, morbidity, and health inequities.153

In 2017, the multistakeholder NQF published A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities: The Four I’s for Health Equity that recommended to the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and private payers what policies to enact and actions to implement to systematically advance equity (Supplemental Table 2).135 These approaches must include adequate public funding or subsidization of services for those who cannot afford to bypass queues for urgent services and cost-effective primary care by buying access into the private healthcare market. Workforce policies should build capacity to meet the needs of indigenous peoples, racial/ethnic minority populations, and communities that experience socioeconomic deprivation.99,154

2. Address all determinants of health for individuals and communities with coordinated approaches, integrated funding streams, and shared accountability metrics across health and social sectors. Aotearoa/NZ and the U.S. recognize social determinants of health as key drivers of health inequities,155,156 but successful programs integrating health and social services are mostly at the demonstration stage.

3. Share power authentically with racial/ethnic minorities and promote indigenous peoples’ leadership and self-determination. The Nuka system of care for Alaska Natives shows the power of self-determination, community participation, and indigenous knowledge and leadership. Interventions in healthcare systems and organizations that serve smaller percentages of racial/ethnic minority patients also benefit greatly from collaborative partnerships with these communities. A key principle of quality improvement is that the customer must be the focus.157 Partnering with patients and communities in meaningful, participatory ways where power is shared, is critical for understanding root causes of inequities and successfully designing and implementing solutions, in contrast to imposing top-down programs likely to be flawed even when created with the best intentions. However, empowering racial/ethnic communities does not mean that the state abrogates its responsibilities in achieving health equity. For example, laws and regulations around alcohol and tobacco, healthy foods, and gun violence will require government action to counteract strong industry financial interests.

4. Have free, frank, and fearless discussions about structural racism, colonialism, white privilege,158 and implicit biases, ensuring that policies and programmes explicitly address root causes. Intrinsic motivation and professionalism are important drivers of health equity efforts.151 However, discussions about racism and colonialism remain difficult, and are all too often avoided.159 Robin DiAngelo, PhD, coined the term “white fragility” to describe a state in which racial stress can lead to defensive emotions and behaviors in whites such as anger, fear, guilt, argument, silence, or withdrawal.160 It is critical to develop psychological and emotional awareness and strength in whites to enable them to push past these barriers and engage in meaningful discussions of root causes of inequities. Discomfort cannot be a reason to avoid dialogue, for then “white fragility” would in essence be a tool to perpetuate inequities in the power structure.161

In a 1993 documentary about the Treaty of Waitangi, then Aotearoa/NZ Prime Minister Jim Bolger stated: “How do we make this founding document work for New Zealand….it really has to work for both of us [Māori and non-Māori]….Not to have it as something that forces us to look back, but really forces us to look forward.”162 This statement can be viewed as constructively seeking to look ahead, or conversely devaluing the historical lived experience of the Māori or avoiding a difficult discussion about the oppression and systematic disadvantage resulting from colonialism, racism, and white privilege. The dissolution of Te Kete Hauora, Māori Health Business Unit at the Ministry of Health in 2016, which provided policy advice and equity analyses for the Government’s objective to achieve health equity for Māori, is concerning.131 This department ensured that issues of racial/ethnic minorities remained a priority and spearheaded integration of equity across the whole Ministry. The U.S similarly has a difficult time discussing race, class, and social inequities, worsened recently with divisive rhetoric by elected national leaders.24 Implementing recommendation 1 to have a strong, explicit equity lens in quality of care and payment policies requires honest discussions about the drivers and nature of health inequities,163 and a commitment to dismantling systems of racism and colonialism.

Additional Lessons for Aotearoa / New Zealand

New Zealanders might ask themselves if they have the most appropriate free market signals and support from the state to encourage, develop, evaluate, and disseminate successful models for innovation, equity, and efficiency.164 Both countries struggle with structural issues such as underfunding of primary care compared with hospital care,165 and the U.S. healthcare system has inefficiencies such as the fee-for-service payment system that incentivizes volume rather than quality of care.166 However, given its sheer size and diverse contexts, the U.S. has many interesting emerging models of care and payment across the 50 states including value-based purchasing, value-based insurance design,167 accountable care organizations,109 and bundled payments168 that have spurred innovative interventions. These models and settings vary in the extent they emphasize collaborative and competitive market-based principles. Good and bad examples exist of each model, and key is finding the right mix and design of interventions for specific patient, population, organizational, and market contexts to achieve health equity.169

A combination of seed money from private foundations, demonstration project funding such as that from the CMMI, competitive marketplaces, and federal funding streams (for example, accountable care organizations, shared savings plans) help nurture and incentivize innovation.170 The Affordable Care Act includes a provision by which any of CMMI’s demonstration programs that improves quality without raising costs or reduces costs without reducing quality can be enacted automatically into the core Medicare and/or Medicaid programs without approval by Congress.171 In addition, robust quality improvement and academic research and evaluation efforts study and disseminate the results of demonstrations. In Aotearoa/NZ there is the opportunity to foster innovative models that drive health equity through national and local government forming truly collaborative partnerships with Māori, Pacific peoples and other communities, where power is shared equitably. Supported by philanthropy, social enterprise and not-for-profit organisations, corporations, non-governmental organisations and academia, such partnerships could potentially nurture, incentivize, and evaluate pro-equity demonstration programs that lead to equitable outcomes.

Additional Lessons for the United States

The U.S. should question whether it has its national cultural values appropriately balanced. From a Western American ethical lens, the U.S. overweights liberalism’s principles of individualism and freedom from the state out of proportion to principles of communitarianism and distributive justice. Or, as the American historian David Hackett Fischer argues, New Zealanders prioritize fairness while Americans value freedom.172 This statement is very much an oversimplification, as Aotearoa/NZ exhibits considerable tensions between neoliberal viewpoints and support for the social welfare state,15,173 and some citizens care about egalitarianism, poverty, and homelessness until they have to pay higher taxes.174 However, Aotearoa/NZ does have a higher floor for its safety net than the U.S.85 The Māori concept of whānau values the family and community.104 Scholars and thought leaders ranging from Robert Putnam to David Brooks lament the loss of community in America.175,176 Thus, America still allows 28 million people to be uninsured,177 and much of the debate around health reform focuses on individual rights and liberties rather than health outcomes for people.178

Conclusions

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation need to be optimized to achieve health equity.151 Nations need to truly value and prioritize equitable health outcomes to create the policies, incentives, and governing structures that will allow best practices to occur, and to close the gap between highlevel policy intent and equitable health outcomes in the population. Success will require free, frank, and fearless discussions about the causes of inequities and a society’s underlying values, measurement and monitoring of inequities, root cause analysis of these inequities, tailored interventions addressing community needs, and cross-sectoral collaboration and integrated funding to address underlying social determinants of health.

Our paper is limited by our perspectives, although we purposely assembled an eclectic study team and set of internal reviewers. Nonetheless, both Aotearoa/NZ and the United States have significant room for improvement in health equity compared to many Western nations, and fail on the Commonwealth Fund’s report card for equity.38 Neglecting to address these inequities with approaches known to be effective is a tremendous waste of human potential and societal productivity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

To improve health equity, nations should:

Explicitly design quality of care and payment policies to achieve equity

Hold the healthcare system accountable through public monitoring and evaluation

Address determinants of health for individuals and communities across sectors

Share power with racial minorities and promote indigenous peoples’ self-determination

Have free, frank, fearless discussions about structural racism, colonialism, and white privilege

Acknowledgments and Conflict of Interest Statement

Funding: Dr. Chin was a William Evans Visiting Fellow in the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine at the University of Otago, Dunedin. For this paper, he was partially supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research [grant number NIDDK P30 DK092949] and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Solving Disparities Through Payment and Delivery System Reform Program Office. The sponsors had no role in study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the article; and in the decision to submit it for publication.

Declarations of Interest: Dr. Chin co-chairs the National Quality Forum Disparities Standing Committee. He is also a consultant to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) disparities portfolio and co-directs the Merck Foundation Bridging the Gap: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes Care National Program Office.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Prior Presentations: This paper was presented in part at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conference “Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity Disparities: Enhancing Lifestyle and Self-Management,” October 24, 2017, Bethesda, Maryland, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Health Care Systems and Disparities Research Seminar, November 8, 2017, Washington, D.C.

We would like to thank the feedback of our colleagues from Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States on a prior version of this paper.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Health systems topics: Equity. World Health Organization 2017; http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 2.Braveman P A new definition to guide future efforts and measure progress. Health Affairs Blog June 22, 2017; http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/06/22/a-new-definition-of-health-equity-to-guide-future-efforts-and-measure-progress/. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 3.Braveman P What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129 Suppl 2:5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Commission on Social Determinants of Health−Final Report. 2008; http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/. Accessed March 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Development Programme. Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html. Accessed April 28, 2018.

- 7.Mills C, Reid P, Vaithianathan R. The cost of child health inequalities in Aotearoa New Zealand: a preliminary scoping study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the economic burden of racial health inequalities in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(2):231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin MH. Creating the business case for achieving health equity. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):792–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nerenz DR, Liu YW, Williams KL, Tunceli K, Zeng H. A simulation model approach to analysis of the business case for eliminating health care disparities. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robson B, Harris R, eds. Hauora: Màori Standards of Health IV A study of the years 2000–2005. Wellington: Te Ropu Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pomare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cormack DM, Harris RB, Stanley J. Investigating the relationship between socially-assigned ethnicity, racial discrimination and health advantage in New Zealand. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e84039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, ed. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruth Dean A., Roger and Me: Debts and Legacies. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Justice Daniels N., health, and healthcare. Am J Bioeth. 2001;1(2):2–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashbrooke M The Inequality Debate: An Introduction. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Worldometers. Countries in the world by population (2017). 2017; http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/. Accessed September 11, 2017.

- 18.Nationmaster. Country vs. country: New Zealand and United States compared: geography stats. 2017; http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/compare/New-Zealand/United-States/Geography. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- 19.Stats NZ. Ethnic group (total responses) by age group and sex, for the census usually resident population count, 2001, 2006, and 2013 Censuses. http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE8021. Accessed March 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Bureau. ACS Demographic and housing estimates: 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed March 24, 2018.

- 21.Abrams MK, Moulds D. Integrating medical and social services: a pressing priority for health systems and payers. Health Affairs Blog. 2016; http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/07/05/integrating-medical-and-social-services-a-pressing-priority-for-health-systems-and-payers/. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 22.Feinglass J, Norman G, Golden RL, Muramatsu N, Gelder M, Cornwell T. Integrating Social Services and Home-Based Primary Care for High-Risk Patients. Popul Health Manag. 2017. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crenshaw K Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989:140. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan JY, Baig AA, Chin MH. High Stakes for the Health of Sexual and Gender Minority Patients of Color. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1390–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crenshaw K Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. 1991:1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Came HA, McCreanor T, Doole C, Simpson T. Realising the rhetoric: refreshing public health providers’ efforts to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi in New Zealand. Ethnicity & Disease. 2017;22(2):105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conway M Environmental Scanning: What It Is and How to Do It…. Thinking Futures; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilburn A, Vanderpool RC, Knight JR. Environmental Scanning as a Public Health Tool: Kentucky’s Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Project. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health. Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2015. 3rd ed. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blakely T, Tobias M, Atkinson J, Yeh L, Huang K. Tracking Disparity Trends in Ethnic and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Mortality, 1981–2004. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rumball-Smith JM. Not in my hospital? Ethnic disparities in quality of hospital care in New Zealand: a narrative review of the evidence. N Z Med J. 2009;122(1297):68–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen P, Bacal K, Crengle S. He Ritenga Whakaaro: Maori experiences of health services. Auckland: Mauri Ora Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand. The Social Report 2016 – Te purongo orange tangata. 2016; http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/health/life-expectancy-at-birth.html-socio-economic-differences. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 37.Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs. 2012;31(8):1803–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider E, Sarnak D, Squires D, Doty M. Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better US Health Care. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tung EL, Cagney KA, Peek ME, Chin MH. Spatial Context and Health Inequity: Reconfiguring Race, Place, and Poverty. J Urban Health. 2017;94(6):757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGovern L, Miller G, Hughes-Cromwick P. The relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes. Health Policy Brief 2014; Health Affairs, August 21, 2014:http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_123.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 41.Mikaere A Colonising Myths-Maori Realities: He Rukuruku Whakaaro. Wellington: Huaia Publishers & Te Takupu, Te Wananga, o Raukawa; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trask H From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Came H Sites of institutional racism in public health policy making in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris R, Cormack D, Tobias M, et al. The pervasive effects of racism: experiences of racial discrimination in New Zealand over time and associations with multiple health domains. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(3):408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunbar-Ortiz R An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkerson I The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York: Vintage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takaki R Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manying I Anti-Chinese Legislation. Teara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 2015; https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/2173/anti-chinese-legislation. Accessed October 8, 2017.