Abstract

Introduction

Prevention of childhood obesity is an important public health objective. Promoting healthful energy balance related behaviours (EBRBs) in the early years should be a key focus. In Scotland, one in five children are overweight or obese by age 5 years, with levels highest in deprived areas. This study protocol outlines the stages of a feasibility study to translate the highly promising North American Healthy Habits, Happy Homes (4H) a home based, preschool childhood obesity prevention intervention to Scotland (4H Scotland). First, elements of participatory and co-production approaches utilised to: (a) engage key stakeholders, (b) enable inclusive recruitment of participants and (c) adapt original study materials. Second, 4H Scotland intervention will be tested within a community experiencing health/social inequalities and high levels of deprivation in Dundee, Scotland.

Methods and analysis

4H Scotland aims to recruit up to 40 families. Anthropometry, objective and subjective measures of EBRBs will be collected at baseline and at 6 months. The intervention consists of monthly visits to family home, using motivational interviewing and SMS to support healthful EBRBs: sleep duration, physical activity (active play), screen time, family meals. The Control Group will receive standard healthy lifestyle information. Fidelity to intervention will be assessed using recordings of intervention visits. Feasibility and acceptability of study design components will be assessed through qualitative interviews and process evaluation of recruitment, retention rates; appropriateness, practicality of obtaining outcome measures; intervention duration, content, mode of delivery and associated costs. Adaptation through participatory and co-production will support development of 4H Scotland. Process evaluation offers two future directions; advancement towards a definitive, larger trial or routine practice.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was granted ethical approval by the University of Strathclyde’s School of Psychological Sciences and Health Ethics Committee. Results will be disseminated through lay summaries workshops, peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN13385965; Pre-results.

Keywords: feasibility, pre-school, inequalities, obesity prevention, energy balance related behaviours

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Engaging and empowering local people in the research process within areas of high health and social inequality and/or deprivation.

Feasibility testing of a low cost, culturally relevant home-based, pre-school childhood obesity prevention intervention.

Objectively measured energy balance related behaviours and qualitative approach utilised.

Generalisability of study may be limited by a short duration and a small number of participant families.

Introduction

The global public health challenge presented by high levels of childhood obesity has been highlighted relentlessly for a number of years1–3 and many nations now recognise that a whole system approach is required to tackle this complex and multifactorial issue.4–6 Improving energy balance related behaviours (EBRBs) in young children is one important area within a whole system approach because it offers a preventative public health strategy and a focus on early intervention, important not least because of the substantial amount of evidence highlighting that obesity and its health related consequences endure well into and beyond teenage years7 and into adulthood.8 The WHO Ending Childhood Obesity Report2 and Ending Childhood Obesity Implementation Report3 both emphasised the major opportunities for obesity prevention which exist in early life. Emerging data from Western nations suggest that the ‘obesogenic’ environment9 in which we live disproportionately impacts on those growing up and living in areas where there is health and social inequalities. Data from England, have also shown a persistent gap between those living in affluent versus deprived areas in relation to childhood obesity.10 In Scotland, this gap has widened so that, in 2016, obesity risk for children living in the most deprived areas was almost double that of those growing up in the least deprived areas.11 12 A preventative and early intervention approach to improving EBRBs in the preschool years which targets children growing up in communities experiencing economic disparities is therefore critical to both early prevention and to the reduction of social inequalities in obesity risk.

A recent systematic review of 85 papers found that targeted school-delivered, environmental and empowerment interventions to be the three most effective approaches in reducing socio-economic inequalities in obesity.13 Laws et al’s systematic review on the impact of interventions to prevent obesity in young children highlighted common features of successful interventions. For the preschool age group (3 to 5 years) focus on obesity prevention and household routines, weight screening and an educational component for parents were promising, although only 7 of the 32 included studies were based in the home and/or community (as opposed to preschool education or care setting). Interventions that included behaviour change techniques, skills acquisition such as cooking skills, rewards and community based resources were most effective. Elements deemed to be critical were those that were culturally appropriate and included parental engagement.14 Although these strategies seem promising, this review also highlighted the number of home based, early childhood interventions was very limited.

The original 4H randomised trial was interested in intervening to improve obesity related risk factors in early childhood. The study involved 121 racial/ethnic minority or low income families from Boston, USA, who had a child aged 2 to 5 years. During the 6 month intervention, families were encouraged and supported to make changes to four EBRBs (adequate sleep, family meals, limiting TV time and removing TV from bedroom) through telephone calls, text messages and monthly individualised support through motivational coaching with a counsellor who met with them in their own home and targeted family routines. The trial demonstrated efficacy as children in the intervention group had decreased body mass index (BMI)-for-age, increased sleep duration and reduced TV viewing on weekend days compared with controls.15 16 Efficacy in childhood obesity prevention interventions is scarce and difficult to achieve. The 4H trial is therefore notable, possibly because it targets key modifiable EBRBs which operate on both the energy intake and energy expenditure side of the energy balance equation. The 4H intervention was a relatively low cost/low intensity intervention which might be particularly appropriate for groups at especially high risk of obesity and where households are busy and/or where parent availability is limited by time or other factors.

The desire to implement high quality, evidence based research findings into practice is balanced by the need for public health interventions that are inclusive, acceptable to the target population and are practical to deliver in a timely manner after feasibility has been demonstrated.12 Therefore, adaptation of the original 4H study is considered necessary to reflect differences in the context within which it will be implemented. Indeed, recently an adapted version of 4H has been piloted in Guelph, Ontario, with participants in the Canadian version rating their satisfaction with the adapted intervention as high or very high.17

Thus, the current research uses participatory approaches (ie, elements of co-production and community based participatory research) to adapt the original 4H study in order to maximise 4H’s cultural relevance for families with preschool children living in a Scottish community experiencing health and social inequalities and economic deprivation

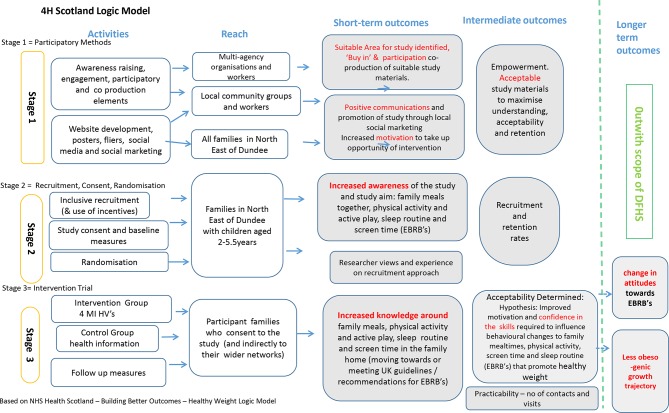

Participatory approaches offer a means to involve potential participants in study processes and provide insight into the context18 in which the research outputs will be applied. Co-production can be drawn on to ensure that the most important asset; that is the people themselves, are empowered and enabled to be involved.19 Features of both co-production and community based participatory research (CBPR)20 were applied to engage and involve key stakeholders in the research process at a local level. A logic model (figure 1), adapted from NHS Health Scotland,21 was developed to provide an overview of the activities at three key stages; engagement of key stakeholders, enablement of inclusive recruitment of participants and adapting original study materials to ensure culturally relevant implementation of 4H Scotland within the North East of Dundee, Scotland.

Figure 1.

4H Scotland logic model.

The present mixed methods feasibility study aims to: (1) describe the participatory process and methods utilised in stage 1 and 2 of the 4H logic model, (2) describe elements of co-production and CBPR that were utilised to enable adaptations of the original 4H study and (3) outline how the feasibility and acceptability of 4H Scotland will be tested and evaluated.

Methods and analysis

The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statement has been used in the preparation of this protocol.

Patient and public involvement

Dundee was chosen as test site of 4H Scotland due to the researcher’s existing links with organisations and people and the high levels of socio-economical deprivation within the city. Based on the Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD), over 35 per cent of the Dundee population live within the most deprived areas of Scotland (SIMD quintile 1).22 In Dundee, more than one quarter of children at primary 1 (age 4 to 5 years) were overweight or obese (ie, had a BMI >85th percentile (UK 1990)), higher than the Scottish average of 22% using measurements from more than 50 000 children as part of the national child health surveillance programme in 2016.23

Participatory approaches (CBPR and co-production) were used to adapt the original 4H study as they offer a useful approach when considering the cultural relevance of an intervention. CBPR promotes equitable involvement of members of the community, local organisations and researchers supports improved knowledge and understanding through nine key principles.20 Co-production is underpinned by key values of equal and reciprocal relationships, being assets based and ‘doing with, not to’19 which reflects the ethos of this study from the outset.

As shown in the logic model, at stage 1, these participatory approaches were utilised to support recruitment into the study, co-production of a study website and posters and adapting existing intervention materials to be culturally relevant. Ongoing and continued contact with a local community action group made up of members of the public, community-based workers and parents is anticipated throughout stage 2 and will allow suitable dissemination of study outcomes to workers and community groups and offer insights into the best format for results to be shared with participants following the intervention trial at stage 3.

Design and setting

An iterative process of dialogue, correspondence via email and attendance at three meetings with multi-agency workforce practitioners; gatekeepers into the local community took place. Meetings were held in community buildings with representatives from health and social care, education, third sector as members of an existing city wide, early years planning group. The aim was to identify a suitable location within Dundee for the study to take place and allow awareness raising and recruitment in that area.

Round table discussions at one planning group meeting identified the North East area as best suited (made up of five neighbourhoods) based on level of highest deprivation, perceived need for such an intervention and absence of similar focused work taking place. Data from the most recent census demonstrates that 39% of households in this area lived in the 15% most income deprived areas in Scotland with figures for two of the neighbourhoods at 65% and 96%, respectively. Profiles for the North East demonstrate the significant health and social inequalities experienced by the community with 58% of the population within one of the neighbourhoods living in the 15% most health deprived areas of Scotland, a domain that includes mortality rates, hospital stays related to drug and alcohol misuse, illness and prescription rates for certain conditions.22

The researcher attended meetings with multi-agency workforce practitioners who signposted to relevant community workers and a community action parent group who became integral to stage 1 and 2 of the study. Five participatory meetings and workshops with this local community action group (described in patient and public involvement section) took place in a health hub situated in the North East area. The participatory meetings facilitated the co-production of a suitable study name for 4H Scotland, acceptable recruitment strategy, development of a study website and adaptation of existing intervention materials for feasibility testing. Outcomes and results will be described in a future process evaluation.

Participant characteristics

4H Scotland aims to recruit up to 40 participant families (with children aged 2.0 to 5.5 years). The sample size will be sufficient to measure important feasibility parameters in a sample of families, with preschool children who live in communities experiencing health and social inequality (including high childhood obesity rates) and economical deprivation. This sample size is similar to a pilot of the 4H study which has recently taken place in the city of Guelph, Canada, where 44 families were involved.17 Data generated in this feasibility study could contribute to sample size and power calculations for subsequent definitive trials or offer insight for application in routine practice.

Recruitment, consent and randomisation

Informed by engagement and insights offered by the community group and multi-agency workforce, recruitment will be inclusive; all families with a child aged 2 to 5.5 years, who live in the North East postcode area, will be eligible to sign-up and enrol in the study. Recruitment will be through promotion and marketing of study website, social media, leaflets, fliers and word of mouth. Interested families will make contact with the researcher via the website or by phone call, text message or email, with this contact initiating a home visit to obtain consent. Families will be offered supermarket vouchers (£20) as an incentive for enrolling in the study and families who have provided written consent will be allocated a study code (a number assigned in sequential order as consent is obtained) and then have baseline measures taken. Participant families will then be randomised to receive either the control or intervention arm. Randomisation will occur following completion of baseline data collection, using a sealed envelope system undertaken by a blinded independent researcher. The study researcher (JG) will be blinded to group randomisation until an envelope with the number corresponding to the study code is opened which identifies the family to be in either the intervention or control group.

Outcome measures and data collection

Data collection will relate to outcomes linked to the adaptations made to original 4H study materials, website development and means of promoting the study that came from the participatory and co-production approach, as shown in stage 1 of the logic model. Stage 2 will have quantitative measure of recruitment and retention rates and a description of researcher views on approach to recruitment. The primary outcome measure related to the intervention trial at stage 3 will be linked to acceptability and practicability of 4H Scotland. In order to understand more about the experiences of participants and to gain insight into the acceptability, a qualitative approach will be used whereby a sample of participants will be interviewed post intervention using a semi-structured interview. Interviews will be conducted with 50% of parents from both intervention and control group. Interviews will take place post intervention and will focus on participants experience of obtaining outcome measures, interaction with the intervention and study materials; barriers and facilitators to intervention delivery including duration, content and mode; pro’s, con’s and areas for improvement.

Insights on intended and unintended outcomes will also be achieved in this way by using open ended questions to understand a wide range of possible outcomes such as changes to family routines or behaviours outwith those linked to EBRBs. Interviews will be conducted by an experienced interviewer, independent of the research, either in the family home or by telephone. Each interview will be transcribed and analysis by the researcher using the Framework method of content matrix data analysis.24

Quantitative methods will measure the number of contacts made with participant families, number of visits attempted versus actual number of intervention visits completed using researcher records and notes.

A range of secondary outcome measures related to EBRBs and BMI z-score will also be collected:

Child physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: measured using the activPAL accelerometer at baseline and 6 months.

Child screen time; measured at baseline and 6 months (described below).

Family eating meals together: measured at baseline and 6 months (described below).

Child BMI z-score: (height and weight measured at baseline and 6 months) height (measured using rigid rule with T piece or stadiometer, Marsden Leicester height measure) and weight (measure using class III electronic scales, seca 875 model).

Child health-related quality of life measured at baseline and 6 months (determined using PedsQLTM parent proxy questionnaire).25

Child body composition (bioelectrical impedance): measured at baseline and 6 months. (body fatness and lean body mass) estimated via supine arm-to-leg bioelectrical-impedence analysis using Bodystat 1500.

For reasons of pragmatism and consistency, the study researcher will carry out all outcome measures at baseline and follow-up. The researcher is experienced in obtaining height, weight and questionnaire data from preschool children and their families. Training in the use of activPAL and Bodystat 1500 will be undertaken. A parent/carer health questionnaire, adapted and shortened from one validated in a preschool study across six European countries between 2012 to 201326 27 will offer subjective insight into family background, frequency of family meals eaten together, screen time, time spent being physically active, sleep routine and duration.

Any changes in secondary outcome measures from baseline to follow-up between the intervention and control will be analysed using repeated measured two-way analysis of variances or other appropriate statistical tests depending on the distribution of the data. An estimate of associated costs related to the intervention could also be calculated. Further detail on assessment of outcome measures and cost will be described later in a process evaluation.

Intervention

4H Scotland will balance the insights offered via participatory and co-production in stage 1 and 2 with adequate representation of the general principles and procedures of the original 4H intervention.16 17 Adaptations of intervention components will be based on pragmatism, researcher (JG) experience and judgement in delivering interventions with families in this context. For example it will offer an alternative, inclusive recruitment methodology as compared with the original 4H which identified eligible families only from health centres. One researcher (JG) will deliver 4H Scotland which provides both consistency and expertise in the approach, having extensive experience of delivering obesity treatment and prevention interventions with preschool children and families using a motivational interviewing (MI) approach and having been trained on the specific 4H intervention from the original 4H researchers.

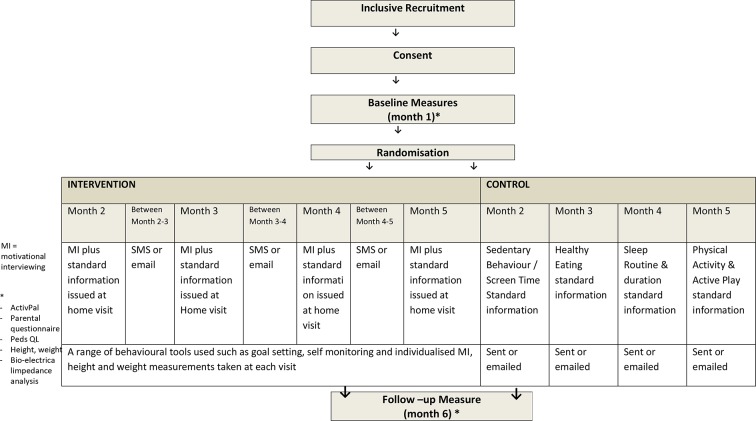

Families randomised to the intervention group will receive monthly visits to the home over 6 months plus contact every 2 weeks via SMS. Families will be supported to make positive lifestyle changes towards meeting or exceeding UK guidelines or recommendations linked to four EBRBs of sleep, physical activity, screen time and family meal routine. The control group will receive general healthy lifestyle information linked to sleep routine, family meals, physical activity and screen time each month mailed or emailed. This information includes materials issued routinely by primary care early years’ health workers in Scotland.

Feasibility study process and intervention fidelity

A summary of the intervention trial process is outlined in (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Feasibility study process.

Intervention fidelity to MI and behaviour change approach at home visits will be assessed. Documentation will enable the researcher to reflect on the appropriate use of and application of behaviour change tools used. A sample of home visits will be audio recorded and analysed by a practitioner experienced and trained in the use of motivational interviewing skills who is independent to the research. A pre-defined checklist adapted from the Scottish Childhood Overweight Treatment Trial28 will evaluate that the intervention was delivered within the spirit of MI.

Process evaluation

As this is a feasibility study, parameters linked to the activities described in stage 1 to 3 of the logic model shown in figure 1 and previously described in ‘outcome measures and data collection section’ will be assessed using process evaluation, supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on process evaluation of complex interventions.29 Process evaluation of stage 1 to 2 will offer detail related to the participatory, co-production approach and adaptations that were made to the original 4H study design, procedures and methods. Stage 3 process evaluation will examine key features of the implementation of 4H Scotland within the North East of Dundee by considering the context, practicability and acceptability of delivery in this setting.

Cost parameters could also be analysed and would be based on those used in an randomised controlled trial of an obesity treatment intervention carried out in Scotland28 and would include: researcher time in lead up, promotion and delivery of intervention; travel; training.

Discussion

This paper uses a logic model to illustrate elements of participatory and co-production approaches (stage 1 and 2) utilised when adapting a preschool, home-based obesity prevention intervention that originated in North America to a Scottish setting. It also outlines the protocol for feasibility testing of the new 4H Scotland randomised controlled trial within Dundee City (stage 3).

It is recognised that engaging people in delivering solutions is necessary for the future of public health interventions3 4 and the importance of empowering interventions such as this has recently been highlighted.12 This current study empowers through involving local people in the research process and using a MI approach to facilitate behaviour change. Berge et al 2016 outlined the use and value of CBPR with ‘play it forward’ a childhood obesity prevention intervention. The intervention was co-created, implemented and evaluated with a community action group over a 3 year period, and offers a useful illustration of the merits of using this type of approach with families.30 While this demonstrates that CBPR has been applied to childhood obesity prevention interventions before, it was not carried out in the UK with families for the preschool age group (2 to 5 years), in the home environment. Consideration must also be given to the potential barriers in utilising this approach namely major challenges related to extra cost and resource (time) required, building trust with the community, equitable participation, differing communication style and conflicting goals.20 31 It is expected that many of these issues will be drawn out and reflected on as part of the later process evaluation of the current study.

A systematic review recently highlighted that very few (less than 10%) high quality studies had looked at interventions to prevent obesity or improve obesity related behaviours in children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families and that, among other things, future studies should therefore develop and evaluate interventions with these groups, at particularly high risk of obesity. The review also recommended that objective measures should be used wherever possible and that an inclusive recruitment method could be helpful in making results more generalisable.13 Hence the intention to do so in 4H Scotland is a strength and has the potential to reduce the marked socioeconomical inequalities in childhood obesity risk in the UK.

An added strength of this study lies in the efficiency of adapting an existing intervention which has demonstrated efficacy in a disadvantaged community, and which has a theoretical and empirical evidence base, rather than developing a completely new intervention. Furthermore, a focus on early years, communities experiencing high levels of health and social inequality and a participatory approach is likely to be appealing to those working in routine practice. Therefore, the feasibility and acceptability of 4H Scotland design and components will be tested and assessed through process evaluation in the hope that it is culturally relevant and suitable to inform either a larger scale trial in keeping with the MRC Framework on developing and evaluating complex interventions32 33 or for direct testing in routine practice.34

Ethics and dissemination

Any amendments to the study protocol will be submitted for ethical approval prior to implementation. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants via parental consent forms. Verbal agreement will be sought from children prior to their enrolment in the study. Findings of the study will be disseminated via summary reports/presentations/workshops to participant families, local people and workers and to public health staff and academics through publication in peer-reviewed journals and presentation at meetings and conferences.

Data management, monitoring and analysis

This study has a data management plan. All data collection and storage procedures will be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant. Only the immediate research team will have access to raw data. A unique identifier code will be assigned to each participant family and notes will be held in locked filing cabinets and transported in secure backpacks. Data will be stored on the University of Strathclyde’s centralised secure data storage system where it will be stored for a maximum of 5 years before being securely destroyed. Data from interviews will be deleted immediately after the transcription, with pseudonyms used in all reports in place of participant’s names. Anonymised data will be available from the University of Strathclyde institutional repository.

Trial status

Study status as of 28 October, 2018: Ethical approval has been granted. All project funding is secured, engagement, participatory and co-production approach is underway. Recruitment of participant families and baseline data collection to be completed by October 2018. The intervention will be ongoing until March 2019. Qualitative and follow-up data collection to be complete by April 2019. Analysis and write up will follow this protocol paper.

Safety procedures

Departmental risk assessment and lone working plans and procedures will be followed. No high-risk activities were identified by risk assessment during ethics application.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The principal investigators (AH, AMG, JJR) are responsible for overseeing the study. The study manager (JG) is responsible for liaising with study participants, coordinating data collection and data management/storage. AH, AMG, JH, ET and JJR will advise on specific aspects of the study including recruitment, data analysis and process evaluation procedures. Any changes to the study protocol will be discussed before the trial registry is updated.

Funding: This work was supported by The Hannah Dairy Research Foundation (HDRF).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was granted ethical approval by the University of Strathclyde ’s School of Psychological Sciences and Health Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. WHO. Population-based approaches to Childhood Obesity Prevention. Geneva: WHO, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity implementation plan: executive summary. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259349/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 07 Nov 2018).

- 4. WHO. Prioritizing areas for action in the field of population based prevention of childhood obesity. WHO Geneva: A set of tools for member states to determine and identify priority areas for action, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butland B, Jedd S, Kopelman P, et al. Foresight tackling obesities: future choices – project report. London: Government Office for Science, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Department of Health. Childhood obesity: a plan of action. London: HM Government, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Geserick M, Vogel M, Gausche R, et al. Acceleration of BMI in Early Childhood and Risk of Sustained Obesity. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1303–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes 2011;35:891–8. 10.1038/ijo.2010.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Government Office for Science. Foresight Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project report. 2nd edn, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Centre of Social Justice. Off the Scales; Tackling England’s childhood obesity crisis. London: The Centre of Social Justice, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tod E, Bromley C, Millard AD, et al. Obesity in Scotland: a persistent inequality. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:135 10.1186/s12939-017-0599-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NHS Health Scotland. Obesity and health inequalities in Scotland summary report: Scottish Public Health Observatory, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bambra C, Hillier FC, Cairns JM, et al. How effective are interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity among children and adults? Two systematic Reviews. 3: Public Health Research, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laws R, Campbell KJ, van der Pligt P, et al. The impact of interventions to prevent obesity or improve obesity related behaviours in children (0-5 years) from socioeconomically disadvantaged and/or indigenous families: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014;14:779 10.1186/1471-2458-14-779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taveras EM, McDonald J, O’Brien A, et al. Healthy Habits, Happy Homes: methods and baseline data of a randomized controlled trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention. Prev Med 2012;55:418–26. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haines J, McDonald J, O’Brien A, et al. Healthy Habits, Happy Homes: randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:1072-9 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haines J, Douglas S, Mirotta JA, et al. Guelph Family Health Study: pilot study of a home-based obesity prevention intervention. Can J Public Health 2018;109:549–60. 10.17269/s41997-018-0072-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Craig P, Di Ruggiero E, Frohlich KL, et al. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers users and funders of research: Southampton: NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre. 2018.

- 19. Loeffler E, Power G, Bovaird T, et al. Co-Production of Health and Wellbeing in Scotland: Governance International, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons Learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:1463–71. 10.1289/ehp.7675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. NHS Health Scotland. Logic model. 2017. http://www.healthscotland.com/OFHI/Obesity/models/HealthyWeightStrategic.gif (Accessed 07 Nov 2018).

- 22. Dundee Partnership. Dundee North East Census Profile. 2012. https://www.dundeecity.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/LCPP_NorthEast_Profile_0.pdf (Accessed 28 Oct 2018).

- 23. Information Services Division (ISD). Scotland Body Mass Index of Primary 1 Children In School Year 2015/16. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Child-Health/Publications/2016-12-13/2016-12-13-P1-BMI-Report.pdf (Accessed 28 Oct 2018).

- 24. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research : Bryman A, Burgess RG, Analyzing Qualitative Data: Taylor & Francis Books Ltd, 1994:173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25. James W. PedsQLTM Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory TM1998-2018 James W. Varni, Ph.D. © Mapi Research Trust.

- 26. Manios Y. The ‘ToyBox-study’ obesity prevention programme in early childhood: an introduction. Obesity Reviews 2012;13:1–2. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manios Y. ToyBox-study group. Methodological procedures followed in a kindergarten-based, family-involved intervention implemented in six European countries to prevent obesity in early childhood: the ToyBox-study. Obes Rev 2014;15(S3):1–4. 10.1111/obr.12178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hughes AR, Stewart L, Chapple J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a best-practice individualized behavioral program for treatment of childhood overweight: Scottish Childhood Overweight Treatment Trial (SCOTT). Pediatrics 2008;121:e539–46. 10.1542/peds.2007-1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Medical Research Council. Evaluating and developing complex interventions. https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/ (Accessed 07 Nov 2018).

- 30. Berge JM, Jin SW, Hanson C, et al. Play it forward! A community-based participatory research approach to childhood obesity prevention. Fam Syst Health 2016;34:15–30. 10.1037/fsh0000116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles : Minkler M, Wallerstein N, In:Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass, 2013:56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hawkins J, Madden K, Fletcher A, et al. Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2017;17:689 10.1186/s12889-017-4695-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.