Abstract

Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) is a vexing and poorly understood autoimmune process involving the upper face and tissues surrounding the eyes. In TAO, the orbit can become inflamed and undergo substantial remodeling that is disfiguring and can lead to loss of vision. These are currently no approved medical therapies for TAO, the consequence of its uncertain pathogenic nature. It usually presents as a component of the syndrome known as Graves’ disease where loss of immune tolerance to the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) results in the generation of activating antibodies against that protein and hyperthyroidism. The role for TSHR and these antibodies in the development of TAO is considerably less well established. We have reported over the past 2 decades evidence that the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) may also participate in the pathogenesis of TAO. Activating antibodies against IGF-IR have been detected in patients with GD. The actions of these antibodies initiate signaling in orbital fibroblasts from patients with the disease. Further, we have identified a functional and physical interaction between TSHR and IGF-IR. Importantly, it appears that signaling initiated from either receptor can be attenuated by inhibiting the activity of IGF-IR. These findings underpin the rationale for therapeutic targeting IGF-IR in active TAO. A recently completed therapeutic trial of teprotumumab, a human IGF-IR inhibiting antibody, in patients with moderate to severe, active TAO, indicates the potential effectiveness and safety of the drug. It is possible that other autoimmune diseases might benefit also benefit from this treatment strategy.

Introduction

Thyroid associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) encompasses the ocular manifestations of the autoimmune syndrome known as Graves’ disease (GD) (Smith and Hegedus 2016). The thyroid dysfunction associated with GD is attributable to loss of immune tolerance to the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) and the generation of activating antibodies against that protein. Further, hyperthyroidism, a central manifestation of GD, can be easily treated with commonly used and effective anti-thyroid medications, radioactive iodine ablation of the thyroid gland, or surgical thyroidectomy. This pattern of treatment has been established in developed countries for several decades. In contrast, no US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA)-approved medical therapies are currently available for TAO, a disfiguring and potentially sight-threatening disorder. Inadequate treatment of TAO represents a major unmet public health need. In TAO, the upper face and connective tissues surrounding the eye can become inflamed and undergo extensive remodeling (Wang, et al. 2015) (Fig. 1). This results in edema, fat redistribution, and fibrosis. These changes can have dramatically deleterious consequences on the function of tissues adjacent to the eye, such as the eyelids and extraocular muscles. The factors underlying TAO remain uncertain but appear to be very similar to those initiating the thyroid glandular processes responsible for hyperthyroidism in GD. Despite substantial barriers imposed by inexact animal models of human disease and difficulties in accessing human tissues for interrogation at the most informative disease stages, a number of recent advances have been made in understanding TAO. Some of these insights have resulted from studies, mostly conducted ex vivo, prompted by the empirical testing of hypotheses challenging conventional wisdom. Prominent among them are concepts supporting the potential involvement of the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) pathway in TAO. This line of inquiry was triggered by observations made earlier that the IGF-I and TSH pathways intersect functionally and that IGF-1 might regulate immune function. Professional immune cells including T and B lymphocytes and monocytes express functional IGF-I receptors (IGF-IR), respond to IGF-I, and produce IGF-I. This suggests that the pathway may serve as an autocrine/paracrine loop involved in regulating immune surveillance. Recent detection of anti-IGF-IR antibodies in patients with GD and the demonstration of physical and functional interactions between IGF-IR and TSHR have identified a novel potential therapeutic target in TAO. Results from these in vitro studies have elicited substantial criticism. Despite this skepticism, the great potential for interrupting the activities of IGF-IR effectively and safely treating active TAO has been revealed with the completion of a clinical trial involving the IGF-IR inhibitory monoclonal antibody, teprotumumab (Smith, et al. 2017). Its potential for application to other autoimmune diseases seems obvious and deserves serious consideration.

Figure 1.

Facial portrait of a patient with relatively mild, asymmetric thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. The patient manifests bilateral upper eyelid retraction, periornital swelling, and mild conjunctival inflammation.

Historical perspectives of IGF-IR as a therapeutic target in human disease

Shortly after its molecular cloning, IGF-IR and its associated pathways were considered potential targets for disease therapy. Given the early recognition that IGF-I and IGF-II exerted important influence on cell survival and proliferation, this pathway was examined for its potential role in the pathogenesis of certain forms of cancer. Many studies have demonstrated effects in vitro of IGF-IR-inhibitory agents on cell proliferation (Tracz, et al. 2016). A role for IGF-I and components of its effector system in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer is supported strongly by preclinical experimental results (Vigneri, et al. 2015). The elevations in IGF binding proteins found in cancer are inconsistent and may be tumor-specific. For instance, ovarian cancer may be associated with elevations in IGFBP1 and IGFBP2 but not IGFBP3 or IGF-I (Gianuzzi, et al. 2016). In old men, IGFBP3 is elevated in colon cancer and the abnormalities appear to be independent of IGF-I levels (Chan, et al. 2017). The IGF-I pathway may play important roles in both prostate cancer initiation and progression (Cao, et al. 2014). Moreover, IGF-IR had been found to be overexpressed in neoplastic diseases. Several independent programs based in pharmaceutical companies began developing molecules that could interrupt the IGF-I pathway as potential therapies for cancer. These included both monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors targeting IGF-IR. Several tumor types, including prostate, lung, colon, and ovarian carcinomas and several sarcomas have been examined in clinical trials with anti-IGF-IR antibodies administered alone and in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. Despite the growing evidence that abnormalities of IGF-I, IGFBPs, and IGF-IR are involved in the pathogenesis of many forms of cancer, it appears that treatment with agents targeting the IGF-IR pathway in unselected disease will remain unrewarding (Philippou, et al. 2017). There is a widespread opinion that identification of predictive biomarkers allowing stratification of cases likely to respond to these agents will be necessary (You, et al. 2014). Therefore the effort to develop molecules targeting IGF-IR for cancer has been essentially curtailed (Qu, et al. 2017). Despite the disappointing results concerning efficacy in cancer, invaluable experience in administrating these drugs to relatively large cohorts of patients, many of whom were physiologically fragile, and the accumulation of substantial safety data has facilitated opportunities for repurposing these molecules. This was the case surrounding the emergence of teprotumumab as a potential candidate for evaluation in patients with active, moderate to severe TAO.

Clinical characteristics of TAO

TAO remains a vexing and poorly managed component of GD, an autoimmune syndrome exhibiting a distinct female bias (Smith and Hegedus 2016). Approximately 40% of patients with GD develop clinically impactful TAO at some point during their lifetime. The interval separating onset of thyroid dysfunction and ocular disease is extremely variable, ranging from coincidental to divergent by several decades. TAO can present initially with vague signs and symptoms, including eyelid retraction and periorbital edema, ocular dryness, and excessive tearing. These manifestations can linger, improve spontaneously, or worsen. More than 50% of those developing TAO have ocular disease limited to these relatively minor manifestations. This group of patients rarely requires systemic therapy and can be managed with topical treatments. The typical course of active TAO lasts 2–3 years (Rundle and Wilson 1945) during which time anti-inflammatory medications may improve the discomfort. This disease activity culminates in the stable (inactive) phase where progression ceases and many of the signs of inflammation resolve. The majority of cases involve both eyes but frequently the severity of TAO is asymmetric. Development of diplopia and proptosis can diminish the quality of life substantially. Proptosis can result in substantial anterior eye surface exposure which if severe can lead to sight-loss. It results from increased volume of the orbital contents, which is the consequence of enlargement of the extraocular muscles and expansion of orbital fat. Both can lead to compression of the optic nerve, a process known as optic neuropathy which, if uncorrected, can also lead to irreversible vision loss.

Current therapy for active TAO

Therapy during the active phase, if the disease is sufficiently severe, most often includes systemic glucocorticoids, administered either as a daily oral dose or intravenously as pulse therapy (Bartalena, et al. 2016; Bartalena, et al. 2012). The latter is considered to be less associated with side effects but concerns emerging from liver toxicity have complicated this route of drug administration (Sisti, et al. 2015). Unfortunately, glucocorticoids are effective in providing symptomatic relief in only half of those patients with TAO who receive them and are not considered disease modifying. They do not usually improve proptosis or strabismus. Their major impact in responding patients is the reduction of inflammation. Despite the widely held view that glucocorticoids are effective in TAO, the absence of adequately powered, placebo-controlled trials examining therapeutic benefit continues to cast uncertainty on their importance in this disease. Among the most informative studies of glucocorticoids was the examination of three different cumulative doses of methylprednisolone (2.25 g, 4.98 g, and 7.47 g) in 159 patients with active, moderate to severe TAO (Bartalena et al. 2012). Improvement was greatest in those receiving the highest dosage of the drug where reduction in the clinical activity score and improved ocular motility were observed. Proptosis failed to improve at any dosage. More recently, B cell depletion with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab, has been examined in two small pilot therapeutic trials, each performed at a single institution (Salvi, et al. 2015; Stan, et al. 2015). These two reports came to very different conclusions about the effectiveness of B cell depletion in moderate to severe active TAO. The disparate findings underscore the need for larger, more definitive studies of rituximab. Many practitioners continue to use the drug off-label but barriers in obtaining third party payment for them continues to limit its general availability for this indication. Agents targeting cytokine pathways putatively involved in the pathogenesis of TAO, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, have also been considered for their potential therapeutic utility in TAO (Luo, et al. 2017; Perez-Moreiras, et al. 2014). None has materialized in adequately powered and properly controlled clinical trials that would allow meaningful assessment of the value of this general therapeutic approach. Thus, the clinical management of TAO during its active phase currently remains inadequate and in need of improvement. Once the stable phase has been reached, remedial surgery, including orbital decompression, strabismus surgery (to correct muscle misalignment and diplopia) and eyelid repair can be undertaken. These surgical approaches have become more refined but their outcomes are somewhat unpredictable and they can reactivate stable disease (Baldeschi, et al. 2007).

Pathogenesis of TAO

At the heart of GD is the loss of immune tolerance toward the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) (Smith and Hegedus 2016). The underpinnings of susceptibility to GD reside in genetic, epigenetic and acquired factors (Tomer 2014). Among the candidate genes are CTLA4, CD40, TSHR, PTPN22 and HLA-DRβ1-Arg74. Some of these are shared with related forms of thyroid autoimmunity such as those occurring in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Layered on to the genetic factors are those acquired from the environment, including experiential components, the details of which have yet to be identified. Epidemiological details such as geographical location, diet, previous drug exposure (including vaccinations), and antecedent illness are essentially left unexplored. Until very recently, little was known about the root mechanisms underlying TAO or how they might be related to the hyperthyroidism of GD. Many investigators in the field, including ourselves, strongly suspect that the antigens shared by the orbital connective tissues and thyroid gland in some manner instigate both humoral and cell-mediated autoimmune responses, both systemically and within the orbit. Critical to the current thinking about disease pathogenesis inside the orbit was the discovery that CD34+ fibrocytes, coming from the bone marrow and belonging to the monocyte lineage, uniquely infiltrate the orbit in TAO (Douglas, et al. 2010) (Fig. 2). These cells transition to CD34+ orbital fibroblasts and cohabit the orbit with CD34− orbital fibroblasts, the normal residents of healthy orbits. CD34+ orbital fibroblasts are notably absent in tissues from healthy donors. Fibrocytes are prodigious antigen presenting cells which express high constitutive levels of MHC Class II expression (Chesney, et al. 1997). The differentiation of fibrocytes from CD11b+CD115+Gr1+ monocytes is regulated by CD4+ T cells through their release of several molecular factors (Niedermeier, et al. 2009). On the one hand, IL-4, interferon γ, TNF-α and IL-2 substantially retard fibrocyte differentiation from monocytes through as yet poorly understood mechanisms. In contrast, calcineurin-inhibited T cells enhance fibrocyte development. Fibrocytes themselves can further differentiate into mature adipocytes which accumulate cytoplasmic triglycerides. Alternatively, they can become myofibroblasts, which are important participants in fibrosis and scar formation (Hong, et al. 2007; Moore, et al. 2005). Their differentiation fate is determined by the cues they receive from their microenvironment. If they are treated with TGF-β, they can proceed down the myofibroblast pathway. PPARγ agonists promote their adipogenesis. They traffic to sites of tissue disruption and wound repair through their responses to chemokines such as CXCL-12 (Phillips, et al. 2004). The vast majority of evidence that fibrocytes are physiologically important and involved in human disease derives either from studies performed in animal models or from those conducted using human tissues and cells in vitro. Thus the findings concerning the behavior of these cells in experimental models must be reconciled with future in vivo studies such as those emerging from human therapeutic trials.

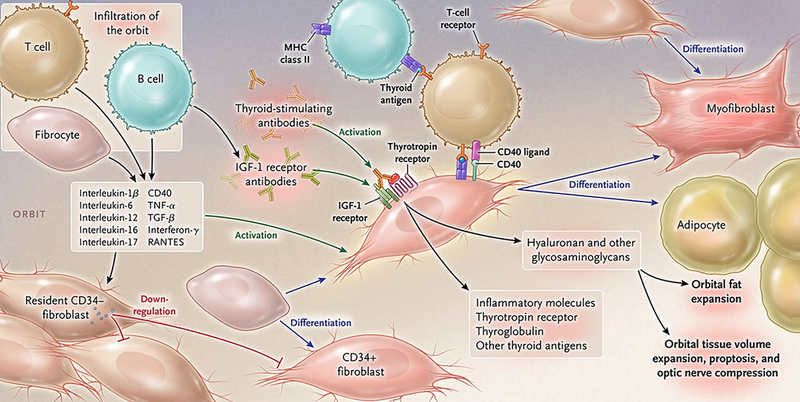

Figure 2.

Theoretical representation: the pathogenesis of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. The orbit becomes infiltrated by B and T cells and CD34+ fibrocytes uniquely in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Bone marrow-derived fibrocytes express several proteins traditionally considered “thyroid-specific”. They can differentiate into CD34+ fibroblasts which in turn can further develop into myofibroblasts or adipocytes depending upon the molecular cues they receive from the tissue microenvironment. CD34+ fibroblasts cohabit the orbit with residential CD34- fibroblasts. These heterogeneous populations of orbital fibroblasts can produce cytokines under basal and activated states. These include interleukins 1β, 6, 8, 10, 16, IL-1 receptor antagonists, tumor necrosis factor α, the chemokine known as “regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted” or RANTES, CD40 ligand and several other cytokines and chemokines. These cytokines can act on infiltrating and residential cells. Like fibrocytes, CD34+ fibroblasts express thyrotropin receptor, thyroglobulin, and other thyroid proteins but at substantially lower levels. Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins and potentially other autoantibodies directed specifically at the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor, activate the thyrotropin/insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 complex, resulting in the activation of several downstream signaling pathways and expression of target genes. Orbital fibroblasts synthesize hyaluronan leading to increased orbital tissue volume. This expanded tissue can result in proptosis and optic nerve compression. Orbital fat also expands from de novo adipogenesis. From N. Engl. J. Med, Smith T.J. and Hegedus L., Graves’ Disease, 375; 1552–1565. Copyright (2016) Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

A notable property of fibrocytes is their capacity to express autoantigens relevant to several diseases, such as type I diabetes mellitus (ICA69, IA2), neuro-inflammatory disorders (myelin basic protein), and GD (Fernando, et al. 2012; Fernando, et al. 2014a; Fernando, et al. 2014b). With specific relevance to TAO, fibrocytes express several “thyroid-specific” proteins, including TSHR, thyroglobulin (Tg), sodium-iodide symporter, and thyroperoxidase (TPO) (Fernando et al. 2012; Fernando et al. 2014a). The expression of these proteins appears to be dependent on the thymic transcription factor, autoimmune regulator protein (AIRE). Of potential importance are the relatively high levels of TSHR displayed by fibrocytes, in some cases comparable to those found on thyroid epithelial cells. The receptor is functional in that both TSH and TSIs induce the synthesis of several cytokines with putative importance in GD. These include IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-23 (Chen, et al. 2014; Fernando et al. 2014a; Li and Smith 2014; Raychaudhuri, et al. 2013). Further, TSH induces pentraxin-3 in fibrocytes (Wang et al. 2015). The detection of extra-thymic AIRE in fibrocytes raises the as yet unanswered question of its role in those cells and whether this expression usually enhances peripheral immune tolerance. Extra-thymic AIRE has been reported previously by Anderson and colleagues in eTac cells as an important component of peripheral tolerance (Gardner, et al. 2008).

As fibrocytes infiltrate the orbit in TAO, their characteristic phenotypic attributes (Pilling, et al. 2009) transition to those that more closely align with residential fibroblasts; however, these derivative fibroblasts retain several fibrocyte markers, including CD34, collagen I, and CXCR4, albeit at substantially reduced levels of expression. Levels of the thyroid proteins and AIRE and the constitutive display of MHC class II are dramatically lessened in these fibroblasts compared to those found in circulating fibrocytes. Moreover, responses mediated through TSHR are considerably less robust in orbital fibroblasts than those found in fibrocytes. Recent evidence strongly suggests that a factor(s) expressed by residential orbital fibroblasts not derived from fibrocytes (ie CD34− orbital fibroblasts) represses expression of these proteins and diminishes the responses to TSH in the CD34+ orbital fibroblasts. However, once CD34+ orbital fibroblasts are purified by cytometric cell sorting and CD34− fibroblasts are removed, levels of the thyroid proteins and responses to TSH are substantially restored (Fernando et al. 2012). Conditioned medium from CD34− fibroblasts down regulates this expression, suggesting that the repression factor is soluble.

Search for an orbital autoantigen in TAO

An early and persistently attractive concept in the development of TAO has been the existence of a shared “thyroid-specific” protein expressed within the orbit. Several antigens have been considered for their potential roles in the orbital disease. Among them, Tg was first detected in the orbit of patients with GD by Kriss and his colleagues in the early 1970s (Kriss 1970). Those workers postulated that the Tg was transported from the thyroid to the orbit, perhaps through lymphatic channels. Characterization of orbital Tg, which could only be found in tissue coming from patients with TAO, was left virtually untouched for several years. Considerably more recent reports from Marino and colleagues contained studies that characterized Tg binding sites in cultured orbital fibroblasts and identified them as harbored on glycosaminoglycans (Lisi, et al. 2002; Marino, et al. 2003). Circulating anti-Tg antibodies are frequently detected in GD and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. They are considered to be both non-specific and non-pathogenic. Similarly, anti-TPO antibodies in the circulation are found widely in thyroid autoimmunity but no role for them in disease development has thus far been identified.

One group failed to detect Tg in the extraocular musculature (Kodama, et al. 1984). They have proposed that extraocular muscles rather than fatty connective tissue are the primary targets in TAO, concluding that muscle proteins harbor the important immunogenic determinants (de Haan, et al. 2010). Their contention has not been supported by convincing experimental evidence. Importantly, late-stage disease in many cases culminates in muscle fibrosis, potentially generating the anti-muscle protein antibodies this group has detected.

TSHR as a relevant orbital antigen in TAO

Since its molecular cloning nearly 30 years ago (Parmentier, et al. 1989), TSHR has been characterized extensively, mainly as a regulatory protein displayed in thyroid tissues. The receptor is a member of the rhodopsin-like G protein coupled receptor family. These integral proteins possess 7 plasma membrane spanning regions (Cornelis, et al. 2001). TSHR comprises a ligand-binding domain located in the extracellular potion of the molecule made up of A and B subunits linked by a disulfide bond (Furmaniak, et al. 1987). A principal mechanism through which TSHR signals downstream pathways involves activation of adenylate cyclase and the generation of cAMP (Kleinau, et al. 2013). Within the thyroid, TSHR mediates the trophic actions of TSH on thyroid function and growth. TSH is a glycoprotein synthesized and released by the thyrotrophs in the anterior pituitary under negative feedback control. There is currently little doubt that TSHR represents the pathogenic, GD-specific autoantigen in GD (Smith and Hegedus 2016). In that disease, TSHR becomes targeted by antibodies that can either activate the receptor, independent of TSH or block the binding and actions of TSH. Ligation of TSHR with activating autoantibodies (Trab, TSI) results in the hyperthyroidism frequently occurring in GD. More recently, the complexity of TSHR signaling in GD has emerged, including the important insight that TSH and TSIs elicit similar but non- identical activation of signaling pathways downstream from the receptor (Latif, et al. 2009; Morshed, et al. 2009).

Besides its display on thyrocytes, TSHR has been detected in several tissues outside the thyroid gland (Endo, et al. 1995; Roselli-Rehfuss, et al. 1992). Many of these are fatty-connective tissues distributed widely in the human body. Its presence in these tissues has prompted inquiry into potential physiological roles in fat regulation, including the influence on cell metabolism and adipocyte proliferation. The presence of TSHR in the orbit carries obvious implications concerning the pathogenesis of TAO (Bahn, et al. 1998; Feliciello, et al. 1993). However, levels of the receptor protein found in fatty connective tissue are considerably lower than those in the thyroid. The roles of either TSHR or its cognate activating antibodies in TAO are considerably less well-established than those occurring within the thyroid gland. Much of the evidence for participation in orbital disease is circumstantial. For instance, a relationship has been identified between the clinical behavior of TAO and levels of these antibodies (Jang, et al. 2013; Kampmann, et al. 2015; Ponto, et al. 2015). While levels seem to be higher in patients with more severe and active TAO, the utility of following antibody levels in a given patient as a guide for clinical management has not been established with properly controlled studies nor is there wide consensus regarding its prognostic value. It must be noted that occasional patients, some with severe TAO, present with undetectable TSIs (Tabasum, et al. 2016). This finding raises the possibility that another pathogenic antigen(s) might also play a role in TAO.

IGF-IR was proposed as a ubiquitous therapeutic target

The type I IGF-IR comprises 1368 amino acids and belongs to a family of structurally related transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors (Lawrence, et al. 2007). Its extracellular domain represents the region of the protein undergoing constitutive receptor dimerization. Once it undergoes cleavage at the second of three fibronectin domains, two polypeptides are formed, designated IGF-IRα and IGF-IRβ. These are linked by disulfide bonds. The IGF-IRα subunit contains the ligand binding site (Whittaker, et al. 2001). IGF-IR is expressed widely in many tissue and cell types. As testament to its far-reaching importance, haploinsufficiency of the pleiotropic transcription factor, MYC, in mice is associated with increased longevity and decreased serum levels of IGF-I (Hofmann, et al. 2015).

Fundamental to the question of whether interrupting the IGF-I pathway might provide clinical benefit to patients with autoimmune diseases is whether the pathway is integrally involved in the regulation of immune function. In fact, the pathway exhibits multiple intersections with the “professional” immune system and with mechanisms involved in host defense. IGF-I can alter cytokine actions as a consequence of the intertwining of the relevant signaling pathways. The IGF-I pathway influences immune function at a variety of levels including processes occurring within the thymus where IGF-I promotes thymic epithelial cell proliferation and intrathymic T cell development and migration (Kooijman, et al. 1995a; Savino, et al. 2002). Professional immune cells, including T and B lymphocytes and cells belonging to the monocyte lineage express functional IGF-IR and respond to physiological concentrations of the growth factor. IGF-I plays important roles in the development of both T and B cells. It enhances thymidine incorporation in human T cells and is chemotactic. These actions are mediated through IGF-IR which is expressed at a higher level in activated cells (Tapson, et al. 1988). The abundance of IGF-IR+ CD45RO memory phenotype T cells is substantially lower than that of IGF-IR+CD45RA+ T cells (Kooijman et al. 1995a). In transgenic mice over-expressing IGF-II, thymic cellularity was substantially increased and the frequency of normal T cells was increased, exhibiting a skew toward CD4+ lymphocytes (Kooijman, et al. 1995b). IGF-I treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with GD could enhance the frequency of CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Pawlowski, et al. 2017). IGF-I produced by bone marrow stromal cells stimulates the development of pro-B cells (Landreth, et al. 1992). It increases the B cell population in lethally irradiated mice (Jardieu, et al. 1994). In the spleen, IGF-I enhances the mature B cell population by provoking cell proliferation (Clark, et al. 1993; Jardieu et al. 1994). The molecule increases DNA synthesis in plasma cells and enhances the effects of IL-6 on these cells (Jelinek, et al. 1997).

The relationship between IGF-I and effector and regulatory immune functions is complex and appears to be tissue context dependent. In a mouse model of intestinal inflammation, IGF-I-primed monocytes can suppress immune inflammation (Ge, et al. 2015). IGF-I reduces klotho expression in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α expression (Xuan, et al. 2017). In contrast, in experimental endotoxin-induced uveitis, an antagonist of growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor attenuated the surge of IGF-I and the generation of proinflammatory cytokines and thus reduced inflammation (Qin, et al. 2014). Osterix-expressing mesenchymal cells generate IGF-I and in so doing, promote pro-B to pre-B cell transition (Yu, et al. 2016). IGF-I activity is important for IL-4-driven macrophage transition to the M2 phenotype and participates in the activation by IL-4 of Akt signaling in those cells (Barrett, et al. 2015). High-dose IGF-I alone and synergistically with dihydrotestosterone alters migration, survival, and adhesion of peripheral lymphocytes by influencing cytokines and paxillin-related signaling proteins (Imperlini, et al. 2015). Thus, the IGF-I pathway appears to regulate, both directly and through interactions with numerous molecules involved in immune function, the magnitude and characteristics of the inflammatory response. Both molecular and cellular environments undoubtedly determine the impact of this pathway on healthy responses and those involved in the development of disease.

Evidence for pathogenic anti-IGF-IR antibodies in GD

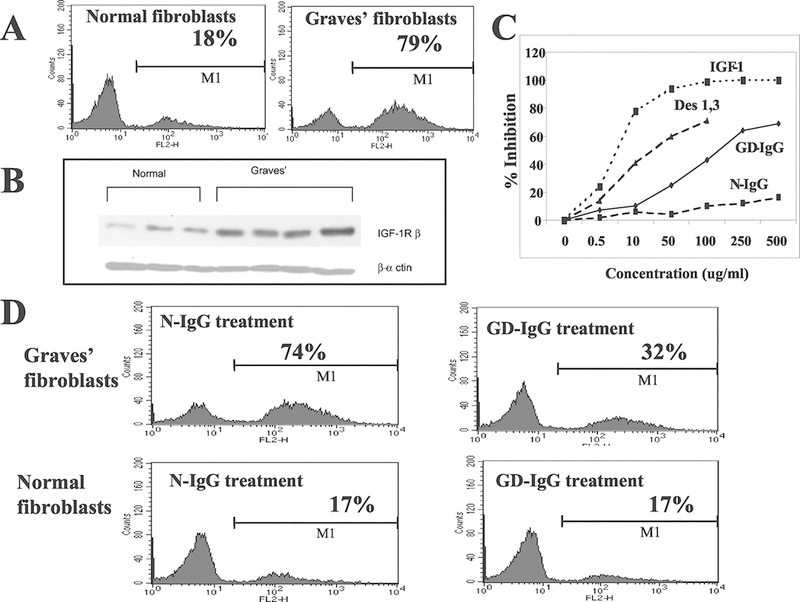

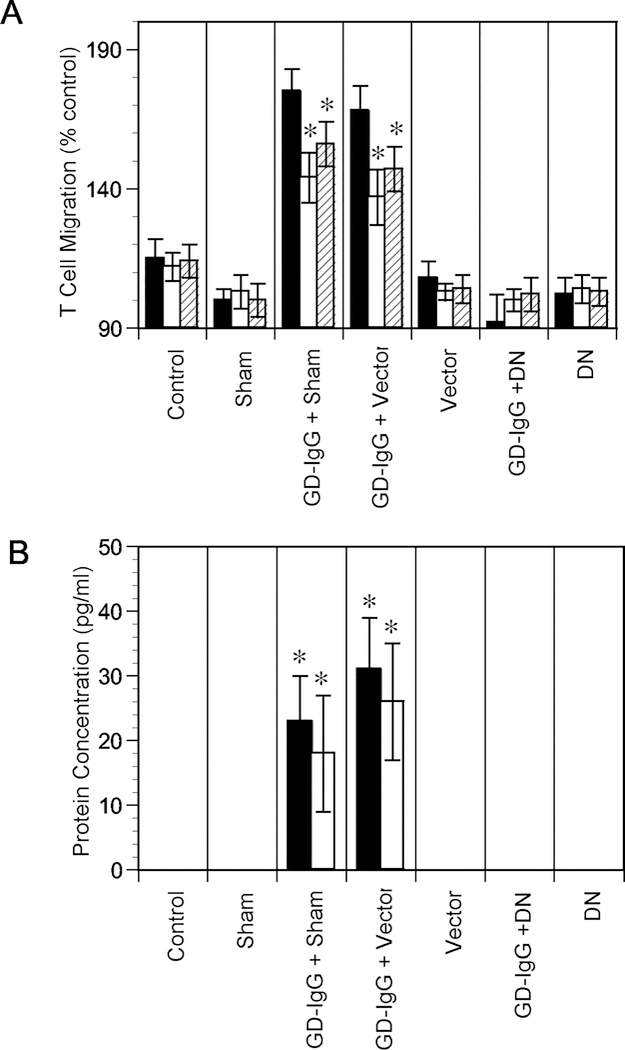

The concept that antibodies targeting IGF-IR might be generated, in addition to those against TSHR, Tg and thyroperoxidase, as a natural consequence of the immune-pathophysiology of GD originated with the report from the group of Kendall-Taylor (Weightman, et al. 1993). In that study, IgGs from patients with GD were shown to displace binding of radiolabeled IGF-I from the surface of orbital fibroblasts. In contrast, immunoglobulins from healthy controls had no impact on IGF-I binding. The study was not designed to assess the potential of these IGF-I-displacing antibodies to initiate signaling in target cells (Weightman et al. 1993). Several years later, Pritchard and colleagues (Pritchard, et al. 2003; Pritchard, et al. 2002) found similar IGF-I displacing activity in IgGs from patients with GD and identified the relevant binding site as IGF-IR using highly-specific IGF-I analogues (Fig 3). They then demonstrated that these IgGs from GD could initiate signaling mediated through the mTor/FRAP/Akt/p70s6k pathway (Pritchard et al. 2002). Moreover, the signaling leads to the induction of two T cell chemoattractant molecules, namely IL-16 and RANTES (Pritchard et al. 2002). These effects were absent in fibroblasts from healthy individuals. The induction of IL-16 and RANTES can be blocked with the IGF-IR inhibitory antibody, 1H7, and by the transfection of a dominant negative mutant IGF-IR, 486/STOP (Fig. 4). This same group also found that IgGs apparently recognizing IGF-IR could induce the generation of hyaluronan in TAO-derived orbital fibroblasts, actions again absent in cultures from healthy donors (Smith and Hoa 2004). These findings have proven to be controversial. Several investigators in the field have attempted to detect activating anti-IGF-IR antibodies in patients with TAO but were unsuccessful (Krieger, et al. 2016; Minich, et al. 2013; Wiersinga 2011). It is notable that those attempts at replicating the original observations involved experimental systems differing substantially from the one used by Pritchard et al (Pritchard et al. 2003; Pritchard et al. 2002; Smith and Hoa 2004). One study was able to identify a subset of patients with TAO in whom activating anti-IGF-IR antibodies could be detected (Varewijck, et al. 2013). These disparate findings have led some investigators to conclude that the only fibroblast-activating antibodies in GD are those directed at TSHR. Absent from some of those discussions dismissing the existence of anti-IGF-IR antibodies in GD has been the detection of these same IGF-1R-activating antibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Pritchard, et al. 2004) and the consistent generation of anti-IGF-IR immunoglobulins in an animal model of the GD (Moshkelgosha, et al. 2013). There are a number of potential explanations for the divergent results thus far obtained by different laboratory groups, not the least important of which is the lack of experimental standardization. Among the differences in these studies has been the use of different target cells, use of animal sera in which levels of IGF-I and IGF-I binding proteins were not determined, and use of assays potentially possessing insufficient sensitivity. Clearly, additional studies are required which would properly control for these and other likely factors.

Figure 3.

(Panel A) Cell surface IGF-IR expression by normal and GD orbital fibroblasts. (Panel B) Western analysis of IGF-IRβ in normal and GD orbital fibroblasts. (Panel C) Displacement of [125I]IGF-I binding with increasing concentrations of unlabeled IGF-I, the IGF-IR-specific IGF-I analogue, Des(1–3), IgG from patients with GD (GD-IgG) and that from heathy controls (N-IgG). (Panel D) Displacement of FITC-conjugated anti-IGF-IR binding by N-IgG (left panels) and GD-IgG (right panels) in GD orbital fibroblasts (upper panels) and those from healthy controls (normal; lower panels). From J. Immunol, Pritchard J, et al, Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant expression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ disease is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway, 170:6348–6354, 2003.

Figure 4.

A dominant negative mutant (DN, 486/STOP) IGF-IR or empty vector was transiently transfected into GD orbital fibroblasts. The mutant protein attenuated chemoattractant activity and expression. (Panel A) T cell chemoattractant activity was assessed by treating cultures with GD-IgG (100 ng/ml) or nothing for 24 h. Media were analyzed for T cell migratory activity without (solid columns) or with either anti-IL-16 (empty columns) or anti-RANTES (stripped columns) neutralizing Abs (5 g/ml), (Panel B) IL-16 (solid columns) and RANTES (empty columns) protein expression. From J. Immunol, Pritchard J, et al, Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant expression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ disease is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway, 170:6348–6354, 2003.

Evidence for IGF-IR/TSHR interplay

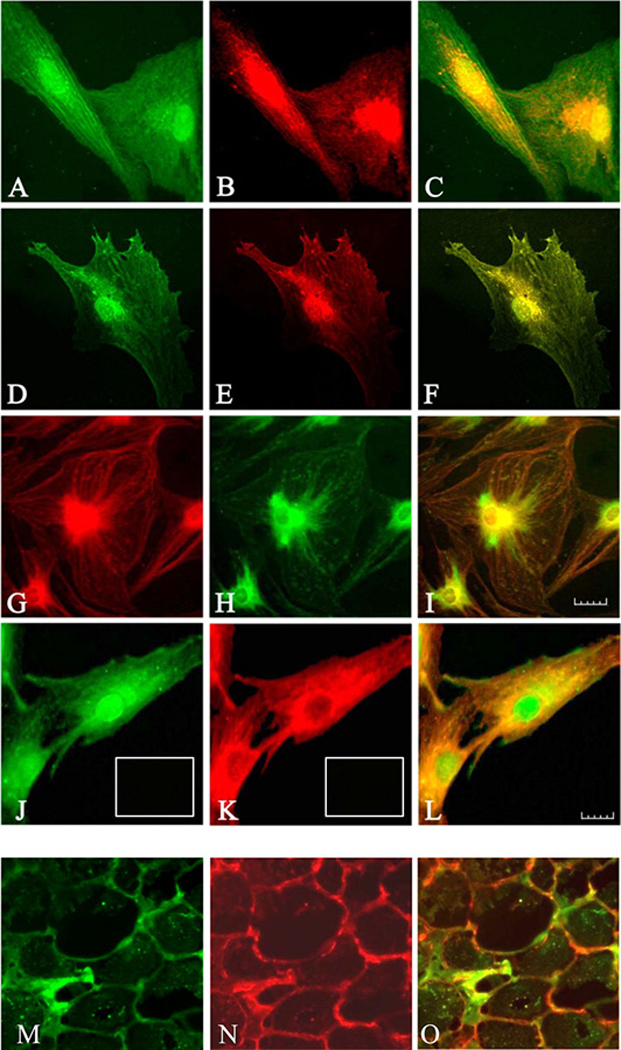

Initial clues that IGF-I and TSH pathways might functionally interact were provide by the studies of Ingbar and colleagues (Tramontano, et al. 1986). They were later followed by the work of other investigators demonstrating that IGF-I and insulin could enhance the actions of TSH on thyroid epithelial cells in culture, including cell proliferation and tyrosine kinase activities (Takahashi, et al. 1991; Tramontano et al. 1986). Importantly, conditional knock-out of the IGF-IR gene in thyroid substantially lessens its responses to TSH (Ock, et al. 2013). In contrast, the thyroid of transgenic mice over-expressing IGF-I and IGF-IR selectively in that tissue appears to be more sensitive to the actions of TSH (Clement, et al. 2001). Critical aspects of these interactions have remained uncharacterized; however key insights have begun to emerge. Signal transduction pathways used by the two receptors overlap (Dupont and LeRoith 2001; Latif et al. 2009; Morshed, et al. 2010; Morshed et al. 2009), suggesting the potential for functional interplay between the receptor proteins. Exploration of whether the two proteins actually interact physically yielded direct evidence that IGF-IR and TSHR form a protein complex (Tsui, et al. 2008). The two receptor proteins co-localize (Fig. 5) and can be co-immunoprecipitated from thyroid and orbital cells using highly-specific monoclonal antibodies. Crucially, signaling initiated at either TSHR (with recombinant human TSH) or IGF-IR (with IGF-I) was attenuated with the monoclonal anti-IGF-IR-inhibitory antibody, 1H7 (Fig. 6) (Tsui et al. 2008). Those initial observations were made using primary human thyroid epithelial cells and the end-response was measured as changes from baseline in Erk ½ phosphorylation. Subsequent studies conducted in human fibrocytes and orbital fibroblasts demonstrated that the fully human IGF-IR inhibiting antibody, teprotumumab, could also attenuate the actions of both IGF-1 and TSH (Chen et al. 2014). Among the responses quantified was the induction of IL-6 and IL-8, two cytokines thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of TAO. These findings in aggregate formed the rationale for undertaking a study of clinical effectiveness and safety of teprotumumab in patients with active TAO.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining for IGF-1Rβ (red) and TSHR (green). The images demonstrate co-localization of the two receptor (yellow) by confocal microscopy. (Panels A–C) Graves’ disease orbital fibroblasts and (Panels D-F) thyrocytes. (Panels C and F) Merged images demonstrate co-localization appearing as yellow or orange. (Panels G–I) Images using a different pair of antibodies demonstrate GF-1Rβ (green) and TSHR (red) and colocalization (yellow) in orbital fibroblasts. (Panels J–L) TSHR (green) and IGF-1Rβ (red) in orbital fibroblasts demonstrates different pattern than that for IGF-1Rβ. (Panel L) Merged image (yellow to orange). (Panels M-O) TAO orbital connective tissue stains for TSHR (M, green) and IGF-1R (N, red). (Panel O) Merged images (orange). From J. Immunol, Tsui et al, Evidence for an association between thyroid-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor I receptors: a tale of two antigens implicated in Graves’ disease, 181:4397–4405, 2008.

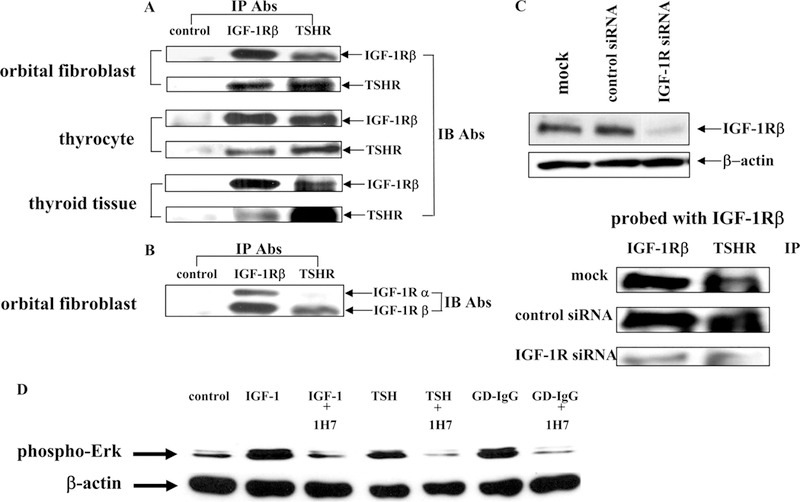

Figure 6.

(Panels A and B) Western blot analysis of proteins from orbital fibroblasts, human thyrocytes, and thyroid tissue that were immunoprecipitated (IP) with either anti-IGF-1R or anti-TSHR antibodies and immunoblotted (IB) with the antibodies indicated. (Panel C) Knocking down IGF-1R expression with siRNA disrupts TSHR/IGF-1R complexes. (Panel D) ERK activation in thyrocytes treated with IGF-1, rhTSH, or immunoglobulins from patients with GD (GD-IgG) without/with anti-IGF-1R monoclonal antibody 1H7 for 15 min. From J. Immunol, Tsui et al, Evidence for an association between thyroid-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor I receptors: a tale of two antigens implicated in Graves’ disease, 181:4397–4405, 2008.

Does interrupting IGF-IR result in clinical benefit of active TAO?

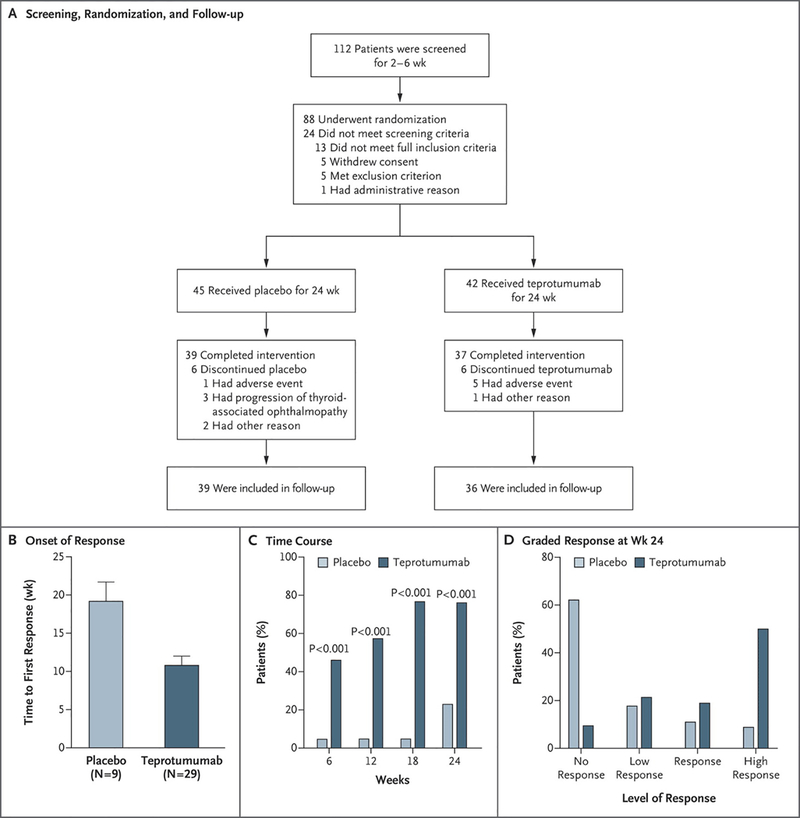

Initial testing of the central hypothesis, that IGF-IR represents a viable therapeutic target in active TAO, was recently completed with the unmasking of a clinical trial where 88 patients with relatively recent onset (within 9 months of study enrolment) moderate to severe TAO were randomized into one of two treatment arms (Smith et al. 2017) (Fig. 7). Patients received either teprotumumab (20 mg/Kg) or saline as 8 infusions over a 24-week treatment period. Enrollees were required to be clinically euthyroid at the time of their participation, thus eliminating the potential for variations in thyroid function to confound interpretation of study results. The primary response endpoint was assessed at 24 weeks and comprised the aggregate of both an improvement ≥ 2 points in clinical activity score (CAS) (on a 7-point scale) and ≥ 2 mm proptosis reduction in the more severely affected eye. Those considered responders were required to not have similar worsening in the fellow (less affected) eye. Secondary responses included improved CAS ≥ 2 points, reduction in proptosis ≥ 2 mm, both measured as continuous independent variables over time, improvement in quality of life as assessed by a fully-validated questionnaire, and subjective improvement in diplopia. At 24 weeks, those receiving teprotumumab exhibited a greater clinical response than did those receiving placebo (p<0.001). In fact, highly statistically significant differences in the two treatment groups was observed at week 6 of the treatment phase (p<0.001). Many cases showed return to premorbid proptosis and CAS scores of 0 (inactive disease). Depending on the durability of these effects, teprotumumab could therefore represent a disease modifying therapy. The results from the trial were unprecedented in that the improvements were equivalent to the best surgical outcomes thus far reported. In theory, therefore, teprotumumab possesses the potential for sparing patients from undergoing major, multi-phased rehabilitative surgery. The safety profile was considered encouraging in that the only adverse events that could be clearly attributed to drug treatment was worsening of glycemic control in a few patients who were diabetic prior to their participation in the study. These cases were managed with adjustment in diabetes medicine. In each case, the medication requirements returned to baseline following the end of the treatment phase. Because no orbital imaging was performed before and immediately following treatment in the study, it remains uncertain whether the effects of teprotumumab were mediated primarily by improvement in the extraocular muscles, the orbital fat, or both. A phase III confirmatory trial is now underway. On the basis of the recently completed trial, the US FDA designated teprotumumab a breakthrough therapy for active TAO.

Figure 7.

Design of the trial and results of primary response. (Panel A) Patients underwent screening underwent randomization to either receive teprotoumumab or placebo administered as 8 IV infusions at 3 week intervals. (Panels B–D) Primary endpoint was assessed at week 24. In panel B, the time to first response was determined. Panel C demonstrates the time course for patients who met responder status. In panel D, responders were graded according to the magnitude of their response.

Mechanism of teprotumumab action

The drug, a fully human IgG1, binds to the cysteine-rich region of IGF-IR with high affinity and specificity. This in turn provokes receptor/antibody complex internalization and its entrance into degradation pathways. Its effects on IGF-I action have been characterized in vitro using a variety of established cell lines and primary cultures. In Ewing’s sarcoma lines TC-32 and TC-71, teprotumumab decreased colony formation in a dose-dependent manner (Huang, et al. 2011). These cells express relatively high levels of IGF-II while the relatively unresponsive cells, A4573 and RD-ES, express extremely low levels of the protein. In primary human fibroblasts and fibrocytes, teprotumumab attenuates the effects of not only IGF-I but also TSH and M22, a monoclonal TSHR-activating antibody (Chen et al. 2014). It is currently uncertain whether teprotumumab possesses physical/biological properties that would render its apparent clinical effectiveness and safety any different from that of other anti-IGF-IR antibodies or small molecule inhibitors of the receptor.

The case for inhibition of IGF-IR in other autoimmune diseases

Among current insights into pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases are bodies of evidence that suggest blocking the IGF-I pathway might provide therapeutic benefit (Smith 2010). Similar to TAO, this pathway might play a significant role in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Pritchard et al. 2004). Polymorphism of a 192 bp allele (cytosine-adenosine repeat) located 1 kb upstream from the transcription start site of the IGF-I gene has been identified (Dhaunsi, et al. 2012). A majority of male non-carriers of the allele had RA. A recent study identified abnormalities in the IGF-I pathway in RA (Szeremeta, et al. 2017). Low circulating IGF-I levels are associated with the severity and activity of the disease (Baker, et al. 2015). T cells express higher levels of miR-223 in RA and lead to lower expression of IGF-I-dependent IL-10 (Lu, et al. 2014). Resistin actions in RA synovium involves the IGF-1R pathway (Bostrom, et al. 2011). Reducing resistin synthesis lowers levels of IGF-1R expression and Akt phosphorylation in human RA synovium implanted in SCID mice. Immunoglobulins that activate IGF-IR on RA synovial fibroblasts have been detected in patients with that disease (Pritchard et al. 2004). Those studies revealed that these IgGs can induce the expression of T cell chemoattractants such as IL-16 and RANTES. The effects are identical to those found when orbital fibroblasts from patients with GD are treated with their own IgGs (Pritchard et al. 2003). Moreover, RA-derived IgG could induce cytokine expression in GD orbital fibroblasts. Other lines of evidence suggest that IGF-IR and other components of the IGF-I pathway might be therapeutically targeted for RA. These include the report from Suzuki et al (Suzuki, et al. 2015) who found elevations in serum IGFBP-3 elevations in patients with active disease. These authors also found that RA synovial fibroblasts synthesize IGF-I which provoked osteoclastic activation and angiogenesis. Those effects could be attenuated with anti-IGF-IR inhibitory antibodies. Similar results were observed with the small molecule IGF-IR inhibitor, NVP-AEW541 (Tsushima, et al. 2017).

Conclusions

The encouraging results recently obtained from the initial trial examining teprotumumab in TAO should provide impetus for moving that drug down the pathway to registration as the first in class therapy for severe disease. But that success might usher in a broader opportunity for developing similar treatments for other autoimmune diseases based on insights into the fundamental pathogenic mechanisms. Clearly, the IGF-I pathway may be therapeutically targeted either with agents inhibiting IGF-IR or some other component of that cascade. Repurposing already-developed drugs seems an ideal solution for orphan diseases such as TAO since in principle it should help overcome economic barriers.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants EY008976, EY11708, DK063121, 5UM1AI110557, Center for Vision core grant EY007002 from the National Eye Institute, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, and by the Bell Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The author has been issued patents while a faculty member at the UCLA School of Medicine covering the diagnostic methods for monitoring anti-IGF-IR antibodies and the therapeutic targeting of IGF-IR in Graves’ disease and other autoimmune diseases. I have requested that my current employer, the University of Michigan Medical School, adjudicate any conflicts of interest.

References

- Bahn RS, Dutton CM, Natt N, Joba W, Spitzweg C & Heufelder AE 1998. Thyrotropin receptor expression in Graves’ orbital adipose/connective tissues: potential autoantigen in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83 998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JF, Von Feldt JM, Mostoufi-Moab S, Kim W, Taratuta E & Leonard MB 2015. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 and Adiponectin and Associations with Muscle Deficits, Disease Characteristics, and Treatments in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol 42 2038–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldeschi L, Lupetti A, Vu P, Wakelkamp IM, Prummel MF & Wiersinga WM 2007. Reactivation of Graves’ orbitopathy after rehabilitative orbital decompression. Ophthalmology 114 1395–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JP, Minogue AM, Falvey A & Lynch MA 2015. Involvement of IGF-1 and Akt in M1/M2 activation state in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Exp Cell Res 335 258–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, Eckstein A, Kahaly GJ, Marcocci C, Perros P, Salvi M, Wiersinga WM & European Group on Graves O 2016. The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy Guidelines for the Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Eur Thyroid J 5 9–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartalena L, Krassas GE, Wiersinga W, Marcocci C, Salvi M, Daumerie C, Bournaud C, Stahl M, Sassi L, Veronesi G, et al. 2012. Efficacy and safety of three different cumulative doses of intravenous methylprednisolone for moderate to severe and active Graves’ orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97 4454–4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom EA, Svensson M, Andersson S, Jonsson IM, Ekwall AK, Eisler T, Dahlberg LE, Smith U & Bokarewa MI 2011. Resistin and insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63 2894–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Lindstrom S, Schumacher F, Stevens VL, Albanes D, Berndt S, Boeing H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Canzian F, Chamosa S, et al. 2014. Insulin-like growth factor pathway genetic polymorphisms, circulating IGF1 and IGFBP3, and prostate cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 106 dju085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YX, Alfonso H, Chubb SAP, Ho KKY, Fegan PG, Hankey GJ, Golledge J, Flicker L & Yeap BB 2017. Higher IGFB3 is associated with increased incidence of colorectal cancer in older men independently of IGF1. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen H, Mester T, Raychaudhuri N, Kauh CY, Gupta S, Smith TJ & Douglas RS 2014. Teprotumumab, an IGF-1R blocking monoclonal antibody inhibits TSH and IGF-1 action in fibrocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 E1635–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney J, Bacher M, Bender A & Bucala R 1997. The peripheral blood fibrocyte is a potent antigen-presenting cell capable of priming naive T cells in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 6307–6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Strasser J, McCabe S, Robbins K & Jardieu P 1993. Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulation of lymphopoiesis. J Clin Invest 92 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Refetoff S, Robaye B, Dumont JE & Schurmans S 2001. Low TSH requirement and goiter in transgenic mice overexpressing IGF-I and IGF-Ir receptor in the thyroid gland. Endocrinology 142 5131–5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis S, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Panneels V, Vassart G & Costagliola S 2001. Purification and characterization of a soluble bioactive amino-terminal extracellular domain of the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochemistry 40 9860–9869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan S, Lahooti H, Morris O & Wall JR 2010. Epitopes, immunoglobulin classes and immunoglobulin G subclasses of calsequestrin antibodies in patients with thyroid eye disease. Autoimmunity 43 698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaunsi GS, Uppal SS & Haider MZ 2012. Insulin-like growth factor-1 gene polymorphism in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Scand J Rheumatol 41 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RS, Afifiyan NF, Hwang CJ, Chong K, Haider U, Richards P, Gianoukakis AG & Smith TJ 2010. Increased generation of fibrocytes in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont J & LeRoith D 2001. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor I receptors: similarities and differences in signal transduction. Horm Res 55 Suppl 2 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Ohta K, Haraguchi K & Onaya T 1995. Cloning and functional expression of a thyrotropin receptor cDNA from rat fat cells. J Biol Chem 270 10833–10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciello A, Porcellini A, Ciullo I, Bonavolonta G, Avvedimento EV & Fenzi G 1993. Expression of thyrotropin-receptor mRNA in healthy and Graves’ disease retro-orbital tissue. Lancet 342 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando R, Atkins S, Raychaudhuri N, Lu Y, Li B, Douglas RS & Smith TJ 2012. Human fibrocytes coexpress thyroglobulin and thyrotropin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 7427–7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando R, Lu Y, Atkins SJ, Mester T, Branham K & Smith TJ 2014a. Expression of thyrotropin receptor, thyroglobulin, sodium-iodide symporter, and thyroperoxidase by fibrocytes depends on AIRE. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 E1236–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando R, Vonberg A, Atkins SJ, Pietropaolo S, Pietropaolo M & Smith TJ 2014b. Human fibrocytes express multiple antigens associated with autoimmune endocrine diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 E796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmaniak J, Hashim FA, Buckland PR, Petersen VB, Beever K, Howells RD & Smith BR 1987. Photoaffinity labelling of the TSH receptor on FRTL5 cells. FEBS Lett 215 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JM, Devoss JJ, Friedman RS, Wong DJ, Tan YX, Zhou X, Johannes KP, Su MA, Chang HY, Krummel MF, et al. 2008. Deletional tolerance mediated by extrathymic Aire-expressing cells. Science 321 843–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge RT, Mo LH, Wu R, Liu JQ, Zhang HP, Liu Z, Liu Z & Yang PC 2015. Insulin-like growth factor-1 endues monocytes with immune suppressive ability to inhibit inflammation in the intestine. Sci Rep 5 7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianuzzi X, Palma-Ardiles G, Hernandez-Fernandez W, Pasupuleti V, Hernandez AV & Perez-Lopez FR 2016. Insulin growth factor (IGF) 1, IGF-binding proteins and ovarian cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 94 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann JW, Zhao X, De Cecco M, Peterson AL, Pagliaroli L, Manivannan J, Hubbard GB, Ikeno Y, Zhang Y, Feng B, et al. 2015. Reduced expression of MYC increases longevity and enhances healthspan. Cell 160 477–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KM, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD & Strieter RM 2007. Differentiation of human circulating fibrocytes as mediated by transforming growth factor-beta and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem 282 22910–22920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HJ, Angelo LS, Rodon J, Sun M, Kuenkele KP, Parsons HA, Trent JC & Kurzrock R 2011. R1507, an anti-insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) antibody, and EWS/FLI-1 siRNA in Ewing’s sarcoma: convergence at the IGF/IGFR/Akt axis. PLoS One 6 e26060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperlini E, Spaziani S, Mancini A, Caterino M, Buono P & Orru S 2015. Synergistic effect of DHT and IGF-1 hyperstimulation in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Proteomics 15 1813–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SY, Shin DY, Lee EJ, Lee SY & Yoon JS 2013. Relevance of TSH-receptor antibody levels in predicting disease course in Graves’ orbitopathy: comparison of the third-generation TBII assay and Mc4-TSI bioassay. Eye (Lond) 27 964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardieu P, Clark R, Mortensen D & Dorshkind K 1994. In vivo administration of insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates primary B lymphopoiesis and enhances lymphocyte recovery after bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol 152 4320–4327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek DF, Witzig TE & Arendt BK 1997. A role for insulin-like growth factor in the regulation of IL-6-responsive human myeloma cell line growth. J Immunol 159 487–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann E, Diana T, Kanitz M, Hoppe D & Kahaly GJ 2015. Thyroid Stimulating but Not Blocking Autoantibodies Are Highly Prevalent in Severe and Active Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy: A Prospective Study. Int J Endocrinol 2015 678194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinau G, Neumann S, Gruters A, Krude H & Biebermann H 2013. Novel insights on thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor signal transduction. Endocr Rev 34 691–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama K, Sikorska H, Bayly R, Bandy-Dafoe P & Wall JR 1984. Use of monoclonal antibodies to investigate a possible role of thyroglobulin in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 59 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman R, Scholtens LE, Rijkers GT & Zegers BJ 1995a. Type I insulin-like growth factor receptor expression in different developmental stages of human thymocytes. J Endocrinol 147 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman R, van Buul-Offers SC, Scholtens LE, Schuurman HJ, Van den Brande LJ & Zegers BJ 1995b. T cell development in insulin-like growth factor-II transgenic mice. J Immunol 154 5736–5745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger CC, Place RF, Bevilacqua C, Marcus-Samuels B, Abel BS, Skarulis MC, Kahaly GJ, Neumann S & Gershengorn MC 2016. TSH/IGF-1 Receptor Cross Talk in Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Pathogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101 2340–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriss JP 1970. Radioisotopic thyroidolymphography in patients with Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 31 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreth KS, Narayanan R & Dorshkind K 1992. Insulin-like growth factor-I regulates pro-B cell differentiation. Blood 80 1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif R, Morshed SA, Zaidi M & Davies TF 2009. The thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor: impact of thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies on multimerization, cleavage, and signaling. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 38 319–341, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MC, McKern NM & Ward CW 2007. Insulin receptor structure and its implications for the IGF-1 receptor. Curr Opin Struct Biol 17 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B & Smith TJ 2014. PI3K/AKT pathway mediates induction of IL-1RA by TSH in fibrocytes: modulation by PTEN. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 3363–3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisi S, Marino M, Pinchera A, Mazzi B, Di Cosmo C, Sellari-Franceschini S & Chiovato L 2002. Thyroglobulin in orbital tissues from patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: predominant localization in fibroadipose tissue. Thyroid 12 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Yu CL, Chen HC, Yu HC, Huang HB & Lai NS 2014. Increased miR-223 expression in T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis leads to decreased insulin-like growth factor-1-mediated interleukin-10 production. Clin Exp Immunol 177 641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo LH, Li DM, Wang YL, Wang K, Gao LX, Li S, Yang JG, Li CL, Feng W & Guo H 2017. Tim3/galectin-9 alleviates the inflammation of TAO patients via suppressing Akt/NF-kB signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 491 966–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M, Lisi S, Pinchera A, Marcocci C, Menconi F, Morabito E, Macchia M, Sellari-Franceschini S, McCluskey RT & Chiovato L 2003. Glycosaminoglycans provide a binding site for thyroglobulin in orbital tissues of patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 13 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minich WB, Dehina N, Welsink T, Schwiebert C, Morgenthaler NG, Kohrle J, Eckstein A & Schomburg L 2013. Autoantibodies to the IGF1 receptor in Graves’ orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BB, Thannickal VJ & Toews GB 2005. Bone Marrow-Derived Cells in the Pathogenesis of Lung Fibrosis. Curr Respir Med Rev 1 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshed SA, Ando T, Latif R & Davies TF 2010. Neutral antibodies to the TSH receptor are present in Graves’ disease and regulate selective signaling cascades. Endocrinology 151 5537–5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshed SA, Latif R & Davies TF 2009. Characterization of thyrotropin receptor antibody-induced signaling cascades. Endocrinology 150 519–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkelgosha S, So PW, Deasy N, Diaz-Cano S & Banga JP 2013. Cutting edge: retrobulbar inflammation, adipogenesis, and acute orbital congestion in a preclinical female mouse model of Graves’ orbitopathy induced by thyrotropin receptor plasmid-in vivo electroporation. Endocrinology 154 3008–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeier M, Reich B, Rodriguez Gomez M, Denzel A, Schmidbauer K, Gobel N, Talke Y, Schweda F & Mack M 2009. CD4+ T cells control the differentiation of Gr1+ monocytes into fibrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 17892–17897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ock S, Ahn J, Lee SH, Kang H, Offermanns S, Ahn HY, Jo YS, Shong M, Cho BY, Jo D, et al. 2013. IGF-1 receptor deficiency in thyrocytes impairs thyroid hormone secretion and completely inhibits TSH-stimulated goiter. FASEB J 27 4899–4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier M, Libert F, Maenhaut C, Lefort A, Gerard C, Perret J, Van Sande J, Dumont JE & Vassart G 1989. Molecular cloning of the thyrotropin receptor. Science 246 1620–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski P, Grubczak K, Kostecki J, Ilendo-Poskrobko E, Moniuszko M, Pawlowska M, Rejdak R, Reszec J & Mysliwiec J 2017. Decreased Frequencies of Peripheral Blood CD4+CD25+CD127-Foxp3+ in Patients with Graves’ Disease and Graves’ Orbitopathy: Enhancing Effect of Insulin Growth Factor-1 on Treg Cells. Horm Metab Res 49 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreiras JV, Alvarez-Lopez A & Gomez EC 2014. Treatment of active corticosteroid-resistant graves’ orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 30 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippou A, Christopoulos PF & Koutsilieris DM 2017. Clinical studies in humans targeting the various components of the IGF system show lack of efficacy in the treatment of cancer. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 772 105–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP & Strieter RM 2004. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest 114 438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B & Gomer RH 2009. Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS One 4 e7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponto KA, Diana T, Binder H, Matheis N, Pitz S, Pfeiffer N & Kahaly GJ 2015. Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins indicate the onset of dysthyroid optic neuropathy. J Endocrinol Invest 38 769–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J, Han R, Horst N, Cruikshank WW & Smith TJ 2003. Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant expression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ disease is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway. J Immunol 170 6348–6354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J, Horst N, Cruikshank W & Smith TJ 2002. Igs from patients with Graves’ disease induce the expression of T cell chemoattractants in their fibroblasts. J Immunol 168 942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J, Tsui S, Horst N, Cruikshank WW & Smith TJ 2004. Synovial fibroblasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, like fibroblasts from Graves’ disease, express high levels of IL-16 when treated with Igs against insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. J Immunol 173 3564–3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin YJ, Chan SO, Chong KK, Li BF, Ng TK, Yip YW, Chen H, Zhang M, Block NL, Cheung HS, et al. 2014. Antagonist of GH-releasing hormone receptors alleviates experimental ocular inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 18303–18308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Wu Z, Dong W, Zhang T, Wang L, Pang Z, Ma W & Du J 2017. Update of IGF-1 receptor inhibitor (ganitumab, dalotuzumab, cixutumumab, teprotumumab and figitumumab) effects on cancer therapy. Oncotarget 8 29501–29518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri N, Fernando R & Smith TJ 2013. Thyrotropin regulates IL-6 expression in CD34+ fibrocytes: clear delineation of its cAMP-independent actions. PLoS One 8 e75100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli-Rehfuss L, Robbins LS & Cone RD 1992. Thyrotropin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid is expressed in most brown and white adipose tissues in the guinea pig. Endocrinology 130 1857–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle FF & Wilson CW 1945. Development and course of exophthalmos and ophthalmoplegia in Graves’ disease with special reference to the effect of thyroidectomy. Clin Sci 5 177–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Curro N, Campi I, Covelli D, Dazzi D, Simonetta S, Guastella C, Pignataro L, Avignone S, et al. 2015. Efficacy of B-cell targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with active moderate to severe Graves’ orbitopathy: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100 422–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savino W, Postel-Vinay MC, Smaniotto S & Dardenne M 2002. The thymus gland: a target organ for growth hormone. Scand J Immunol 55 442–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisti E, Coco B, Menconi F, Leo M, Rocchi R, Latrofa F, Profilo MA, Mazzi B, Albano E, Vitti P, et al. 2015. Intravenous glucocorticoid therapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy and acute liver damage: an epidemiological study. Eur J Endocrinol 172 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ 2010. Insulin-like growth factor-I regulation of immune function: a potential therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases? Pharmacol Rev 62 199–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ & Hegedus L 2016. Graves’ Disease. N Engl J Med 375 1552–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ & Hoa N 2004. Immunoglobulins from patients with Graves’ disease induce hyaluronan synthesis in their orbital fibroblasts through the self-antigen, insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89 5076–5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Kahaly GJ, Ezra DG, Fleming JC, Dailey RA, Tang RA, Harris GJ, Antonelli A, Salvi M, Goldberg RA, et al. 2017. Teprotumumab for Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 376 1748–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stan MN, Garrity JA, Carranza Leon BG, Prabin T, Bradley EA & Bahn RS 2015. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100 432–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Morimoto S, Fujishiro M, Kawasaki M, Hayakawa K, Miyashita T, Ikeda K, Miyazawa K, Yanagida M, Takamori K, et al. 2015. Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor system is a potential therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity 48 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeremeta A, Jura-Poltorak A, Komosinska-Vassev K, Zon-Giebel A, Kapolka D & Olczyk K 2017. The association between insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs), and the carboxyterminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PICP) in pre- and postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 46 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabasum A, Khan I, Taylor P, Das G & Okosieme OE 2016. Thyroid antibody-negative euthyroid Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2016 160008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Conti M, Prokop C, Van Wyk JJ & Earp HS 3rd 1991. Thyrotropin and insulin-like growth factor I regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation in FRTL-5 cells. Interaction between cAMP-dependent and growth factor-dependent signal transduction. J Biol Chem 266 7834–7841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapson VF, Boni-Schnetzler M, Pilch PF, Center DM & Berman JS 1988. Structural and functional characterization of the human T lymphocyte receptor for insulin-like growth factor I in vitro. J Clin Invest 82 950–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer Y 2014. Mechanisms of autoimmune thyroid diseases: from genetics to epigenetics. Annu Rev Pathol 9 147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracz AF, Szczylik C, Porta C & Czarnecka AM 2016. Insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 16 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramontano D, Cushing GW, Moses AC & Ingbar SH 1986. Insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates the growth of rat thyroid cells in culture and synergizes the stimulation of DNA synthesis induced by TSH and Graves’-IgG. Endocrinology 119 940–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui S, Naik V, Hoa N, Hwang CJ, Afifiyan NF, Sinha Hikim A, Gianoukakis AG, Douglas RS & Smith TJ 2008. Evidence for an association between thyroid-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors: a tale of two antigens implicated in Graves’ disease. J Immunol 181 4397–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima H, Morimoto S, Fujishiro M, Yoshida Y, Hayakawa K, Hirai T, Miyashita T, Ikeda K, Yamaji K, Takamori K, et al. 2017. Kinase inhibitors of the IGF-1R as a potential therapeutic agent for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity 50 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varewijck AJ, Boelen A, Lamberts SW, Fliers E, Hofland LJ, Wiersinga WM & Janssen JA 2013. Circulating IgGs may modulate IGF-I receptor stimulating activity in a subset of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneri PG, Tirro E, Pennisi MS, Massimino M, Stella S, Romano C & Manzella L 2015. The Insulin/IGF System in Colorectal Cancer Development and Resistance to Therapy. Front Oncol 5 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Atkins SJ, Fernando R, Wei RL & Smith TJ 2015. Pentraxin-3 Is a TSH-Inducible Protein in Human Fibrocytes and Orbital Fibroblasts. Endocrinology 156 4336–4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weightman DR, Perros P, Sherif IH & Kendall-Taylor P 1993. Autoantibodies to IGF-1 binding sites in thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Autoimmunity 16 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker J, Groth AV, Mynarcik DC, Pluzek L, Gadsboll VL & Whittaker LJ 2001. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of a type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor ligand binding site. J Biol Chem 276 43980–43986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga WM 2011. Autoimmunity in Graves’ ophthalmopathy: the result of an unfortunate marriage between TSH receptors and IGF-1 receptors? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96 2386–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan NT, Hoang NH, Nhung VP, Duong NT, Ha NH & Hai NV 2017. Regulation of dendritic cell function by insulin/IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling through klotho expression. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 37 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L, Liu C, Tang H, Liao Y & Fu S 2014. Advances in targeting insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway in cancer treatment. Curr Pharm Des 20 2899–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu VW, Lymperi S, Oki T, Jones A, Swiatek P, Vasic R, Ferraro F & Scadden DT 2016. Distinctive Mesenchymal-Parenchymal Cell Pairings Govern B Cell Differentiation in the Bone Marrow. Stem Cell Reports 7 220–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]