Abstract

Sex differences in behavior allow animals to effectively mate and reproduce. However, the mechanism by which biological sex regulates behavioral states, which underlie the regulation of sex-shared behaviors, such as locomotion, is largely unknown. In this study, we studied sex differences in the behavioral states of Caenorhabditis elegans and found that males spend less time in a low locomotor activity state than hermaphrodites and that dopamine generates this sex difference. In males, dopamine reduces the low activity state by acting in the same pathway as polycystic kidney disease-related genes that function in male-specific neurons. In hermaphrodites, dopamine increases the low activity state by suppression of octopamine signaling in the sex-shared SIA neurons, which have reduced responsiveness to octopamine in males. Furthermore, dopamine promotes exploration both inside and outside of bacterial lawn (the food source) in males and suppresses it in hermaphrodites. These results demonstrate that sexually dimorphic signaling allows the same neuromodulator to promote adaptive behavior for each sex.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The mechanisms that generate sex differences in sex-shared behaviors, including locomotion, are not well understood. We show that there are sex differences in the regulation of behavioral states in the model animal Caenorhabditis elegans. Dopamine promotes the high locomotor activity state in males, which must search for mates to reproduce, and suppresses it in self-fertilizing hermaphrodites through distinct molecular mechanisms. This study demonstrates that sex-specific signaling generates sex differences in the regulation of behavioral states, which in turn modulates the locomotor activity to suit reproduction for each sex.

Keywords: behavioral state, C. elegans, dopamine, locomotion, neuromodulator, sex

Introduction

Biological sex is a critical regulator of animal behavior, and sex differences in behavior are essential for animals to effectively mate and reproduce (Mowrey and Portman, 2012; Auer and Benton, 2016; McCarthy, 2016). Upon sexual maturation, highly sex-biased behaviors, including mating, courtship, and offspring care, are enhanced. In addition, biological sex differentially regulates sex-shared behaviors, such as feeding and locomotion, in a manner that suits the reproduction for each sex. Emerging evidence suggests that not only sex-specific neuronal structures but also sex-specific modulation of sex-shared neuronal circuits underlie these behavioral differences. However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms for such sexually dimorphic regulation are still largely unknown.

Regulation of behavioral states is implicated in generating sex differences in sex-shared behaviors, including locomotion (Gatti et al., 2000). Animal behavior consists of discrete behavioral states and animals transition between states with different levels of arousal, metabolism, and locomotor activity, such as sleep and waking states. The behavioral states are regulated by the environment and internal condition of an animal through various neuromodulators (Mong and Cusmano, 2016; Ly et al., 2018). Although biological sex affects behavioral states, how neuromodulator signaling is altered in a sexually dimorphic manner to differentially regulate behavioral states is poorly understood.

The two sexes in the model animal Caenorhabditis elegans include the male and the hermaphrodite. Males need to mate with hermaphrodites to reproduce, whereas hermaphrodites can also self-fertilize as they produce both eggs and sperm. In the presence of bacteria, which serve as food, C. elegans hermaphrodites switch between two behavioral states, roaming and dwelling (Fujiwara et al., 2002). Animals in the dwelling state, in which hermaphrodites spend most of their time, move at a low speed while frequently changing their direction by turning. Therefore, dwelling animals remain in a small area. Animals in the roaming state disperse quickly because they exhibit high locomotor activity and a low turning frequency. The behavioral states are regulated by food; time spent in each state depends on food availability and past nutritional status (Shtonda and Avery, 2006; Ben Arous et al., 2009; Churgin et al., 2017). It is shown that neuromodulators, including bioamines, such as dopamine, serotonin, and octopamine (biological equivalent of noradrenalin in invertebrates) (Roeder, 1999), play a role in the regulation of behavioral states in hermaphrodites (Flavell et al., 2013; Churgin et al., 2017; Stern et al., 2017).

C. elegans males have various behavioral characteristics that are different from those of hermaphrodites. Males exhibit mating behavior in which they use their distinct tail structure to locate the vulva of hermaphrodites and copulate (Barr et al., 2018). Males leave a bacterial lawn more frequently than hermaphrodites when there is no mate present (Lipton et al., 2004). This food-leaving behavior is called “mate-searching behavior” and is an indicator of sex drive. When actively moving, males are faster than hermaphrodites because of sexual modifications of the muscle and nervous system functions (Mowrey et al., 2014). However, the behavioral states in males (i.e., how often they are active) have yet been studied.

With the extensive studies on the behavioral states in hermaphrodites and detailed knowledge on sex differences in the structure of the compact nervous system (Sulston et al., 1980; White et al., 1986; Jarrell et al., 2012), C. elegans provides an opportunity to investigate the molecular basis of sex differences in behavioral states. In this study, through quantitative behavioral analyses with genetic and pharmacological techniques in C. elegans, we reveal a significant sex difference in the regulation of behavioral states, where males spend a much longer time in the high activity state than do hermaphrodites. We also show that dopamine plays a role in generating the sex difference by both suppressing the low locomotor activity state in males and increasing it in hermaphrodites through distinct molecular mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Strains.

Culturing and genetic manipulation of C. elegans were performed as previously described (Brenner, 1974). CB4088 him-5(e1490) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:CB4088) was used as the WT strain. The strains used in this study are as follows: DA1774 ser-3(ad1774) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:DA1774), CB1112 cat-2(e1112) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:CB1112), FK2261 cat-2(tm2261), MT15620 cat-2(n4547) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:MT15620), MT15434 tph-1(mg280) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:MT15434), PS3401 lov-1(sy582);him-5(e1490) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:PS3401), CB1370 daf-2(e1370) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:CB1370), PT2248 pdf-1(tm1996);him-5(e1490) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:PT2248), DG2389 glp-1(bn18) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:DG2389), YT17 crh-1(tz2) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:YT17), FK2104 ser-6(tm2104), BA821 spe-26(hc138) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:BA821), PT8 pkd-2(sy606);him-5(e1490) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:PT8), LX702 dop-2(vs105) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:LX702), FK1392 dop-4(tm1392), LX645 dop-1(vs101) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:LX645), FK2385 ntc-1(tm2385), VC224 octr-1(ok371) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:VC224), LX703 dop-3(vs106) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:LX703), RB1161 tbh-1(ok1196) (RRID:WB-STRAIN:RB1161), and FK2735 lgc-53(tm2735).

The following strains of wild isolates of C. elegans and other Caenorhabditis species were also used: CB4856 C. elegans (RRID:WB-STRAIN:CB4856), PB103 C. briggsae him mutant (RRID:WB-STRAIN:PB103), EM464 C. remanei (RRID:WB-STRAIN:EM464), PB4641 C. remanei (RRID:WB-STRAIN:PB4641), and CB5161 C. brenneri (RRID:WB-STRAIN:CB5161).

For genetic crosses to generate strains carrying multiple mutations, the genotypes of the crossed animals were determined by PCR for the deletion mutants, PCR-RFLP for the cat-2(e1112), and visible phenotypes were used for the sperm-deficient, daf, and him mutants.

Image acquisition and data analysis.

For assay plates, 5 ml of molten low peptone-NGM agar (0.25 g/L peptone, 3 g/L NaCl, 17 g/L Agar, 25 mm KPO4, pH 6.0, 5 mm MgSO4, 5 mm CaCl2) was poured into the wells of 90 mm Petri dishes with four compartments (Atect). On the day before recording, 20 μl of OP50 (RRID:WB-STRAIN:OP50) suspension in Milli-Q water was placed on each well of the assay plates. The plates were incubated at 22°C overnight, resulting in thin bacterial lawns with diameters of ∼9 mm. Also, on the day before recording, 10–20 L4 animals were placed onto a 40 mm NGM plate seeded with OP50 and were grown at 20°C for ∼20 h. Males and hermaphrodites were placed onto separate plates to prevent mating.

Adult animals were individually transferred to the wells of the assay plates 15 min before recording. The assay plate was illuminated by an LED ring (CCS) (Kimura et al., 2010). The images of the assay plates were captured using a DMK series USB camera (Imaging Source) with a resolution of 2000 × 1944 pixels, at 1 frame per second for ∼15 min, using the manufacturer-provided software, IC Capture, with Windows PC or gstreamer with Raspberry Pi 3 (Raspberry Pi Foundation).

ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) was used to determine the position of the animals within the bacterial lawn. The area of the bacterial lawn was enlarged by 200 nm and was used as the ROI. For the animals within the ROI, the centroid and the circularity were determined after background subtraction and image binarization. For the analysis of behavioral states, R (Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996) was used to calculate average speed, angular speed, and circularity of 10 s intervals, similarly as previously reported (Ben Arous et al., 2009).

The data points with 10 s average circularity <0.7 were used for cluster analysis because animals in 10 s windows with circularity >0.7 were exhibiting tail-chasing behavior (see below). For the cluster analysis, data from 50 males and 50 hermaphrodites were analyzed with the R package mclust (Scrucca et al., 2016). Data points from 10 s intervals were separated into three clusters. This dataset was then used to conduct discriminant analysis, which allows data points from new samples to be categorized into these classes. First, 10 s averages were calculated for a new sample. Next, if the circularity of a data point was >0.7 (when animals are exhibiting tail-chasing behavior), the data point was categorized as “tail chase.” By the discrimination analysis with mclust, the remaining data points were categorized into the following three classes: roaming (relatively fast movement with low turning frequency), fast turn (fast movement with high turning frequency), and dwelling (slow movement). The fraction of time spent in each class was calculated for each strain.

When testing males of non-C. elegans strains, L4 males were kept together with L4 females or hermaphrodites overnight because most of them escaped the plates if they were kept without their counterparts. For the analysis of L4 animals, L4 males and hermaphrodites were put onto assay plates directly from mix population plates.

Manual scoring and validation of behavioral categories.

To validate the behavioral categorization by the cluster and discriminant analyses, we manually analyzed 10 males and 10 hermaphrodites. Through examination of videos, experimenters manually categorized each 10 s segment into the following four classes: tail chase (animals exhibiting tail-chasing behavior for the majority of time); dwelling (animals with slow movement); fast turn (animals with fast movement, including turns); and roaming (animals with fast movement, but without turns). Then, the correlation coefficients for time spent in each class between the automatic R analysis and the manual analysis were determined.

We also manually examined each frame of the videos and found that males have a circularity of 0.84 ± 0.05 and 0.43 ± 0.05 when they are exhibiting or not exhibiting tail-chasing behavior, respectively. As mentioned above, the threshold of 10 s average circularity for classifying tail chase was set at 0.7. With this threshold, for 10 s segments in which animals exhibited tail-chasing behavior in more than a half of the 10 s, 96.7% were categorized as tail chase. On the other hand, for 10 s segments in which animals exhibited tail-chasing behavior for a half or less of the 10 s, 3.1% were categorized as tail chase.

Drug treatment.

When testing the effect of dopamine in assay plates, 20 μl of 10 mg/ml dopamine was placed over the bacterial lawn on the assay plates. After the plates were dried for 1 h, animals were placed on the bacterial lawn and were recorded after 15 min of resting. For testing the effect of dopamine before the transfer to assay plates, 100 μl of 10 mg/ml dopamine was placed over the bacterial lawn on 40 mm NGM plates. After the dopamine-containing plates were dried for 1 h, L4 animals were placed on the plates and cultured for 20 h. Then animals were transferred to the assay plates (without dopamine) and recorded after 15 min. To test the effect of removal of dopamine, animals cultured on the dopamine-containing plates for 20 h were transferred to dopamine-free NGM plates and incubated for 3 or 6 h, before transferring to the assay plates. For the 3 or 6 h dopamine treatment, L4 animals were placed onto normal NGM plates. After 20 h, animals were transferred to NGM plates with or without dopamine and cultured for 3 or 6 h. Animals were then transferred to assay plates and recorded after 15 min.

For octopamine treatment, 20 μl of 100 mg/ml octopamine was placed on the assay plates over the bacterial lawn. After the plates were dried for 1 h, animals were placed onto these plates and their behavior was recorded 15 min after the transfer.

Transgenic animals for behavioral tests.

cat-2 background animals carrying the WT cat-2 gene and the injection marker glr-3::mcherry (Nagashima et al., 2016) were crossed with him-5 to create cat-2;him-5 carrying the cat-2 gene. To express ser-3 and ser-6 in the SIA neurons, ceh-17::ser-3 and ceh-17::ser-6 (Yoshida et al., 2014) were injected along with the injection marker lin-44::gfp into cat-2;ser-3;ser-6;octr-1;him-5. For masculinization of the nervous system, rab-3::fem-3 (Mowrey et al., 2014) was injected along with the injection marker glr-3::mcherry into him-5 and cat-2;him-5.

Primers ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggcttctctggaatcagtgttcttg and ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggtcgcctggaacagattgataaattc were used to amplify the ceh-17 promoter and the PCR product was cloned into pDONR221 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer's protocol, to create pENTR-ceh-17. Primers cttggtaccggtagaaaaatggaggtggatccgggt and gaattggctagctatcatcgtttcctggagcaatc were used to amplify the coding region of fem-3 using rab-3::fem-3 as the template. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and NheI and cloned into KpnI and XbaI site of pDEST-GCaMP6 (Ohkura et al., 2012) to create pDEST-fem-3. ceh-17::fem-3 was generated by recombination of pENTR-ceh-17 and pDEST-fem-3. ceh-17::fem-3 was injected along with the injection marker glr-3::mcherry into him-5 and cat-2;him-5, to masculinize SIA neurons.

The transgenes were maintained as extrachromosomal arrays, which are only partially stable, causing some progeny to lose the genes. In addition to animals carrying the transgene, animals not carrying the transgene, as determined by the absence of fluorescence, were also tested as controls.

Calcium imaging.

ceh-17::GCaMP6 was generated by recombination of pENTR-ceh-17 and pDEST-GCaMP6 (Ohkura et al., 2012). ceh-17::GCaMP6 was injected into N2 animals together with ceh-17::dsred (Suo et al., 2006) and lin-44::gfp (Murakami et al., 2001) as a coinjection marker. The resulting strain was subjected to UV irradiation to integrate the extrachromosomal array into the genome (Mariol et al., 2013). The strain carrying the integrated transgene was backcrossed to N2 animals three times and then crossed to CB4088 him-5. The resulting strain was crossed with ser-3;ser-6;octr-1;him-5 to obtain octopamine receptor mutants carrying ceh-17::GCaMP6.

Hermaphrodites expressing GCaMP6 were fixed in a previously reported microfluidic device (Chronis et al., 2007). A custom-made device with narrower space (Fluidware Technologies) was used to fix males. The nose tips of the animals were washed with imaging buffer (0.2 g/L gelatin, 5 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgSO4, and 350 mOsm glycerol) for 5 min before recording. Ten minutes after the recording was started, the nose tips of the animals were exposed to the imaging buffer containing 5 mg/ml octopamine. After 10 min, the animals were exposed again to the buffer without octopamine for 5 min. Imaging was performed using an inverted microscope (Axio Observer D1, Carl Zeiss) equipped with an oil-immersion objective lens (UPlanApo, 40×, NA = 1.00, Olympus) and a scientific CMOS camera (ORCA-Flash4.0 V2, Hamamatsu Photonics). Images were acquired every 500 ms using a mercury lamp, 450–490 nm excitation filter, 495 nm dichroic mirror, and 500–550 nm excitation filter (Carl Zeiss), and analyzed with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). ceh-17 promotor induces gene expression in the SIA neurons and the ALA neuron, whose cell bodies are located in the ventral and dorsal side of the head region, respectively. The cell bodies of the neurons in the ventral side were selected as an ROI and tracked with the “Track Objects” plugin in MetaMorph software. The background-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the ROI was calculated for each stack. The fluorescence intensity 5 min before octopamine exposure was averaged and defined as F. The change in the fluorescence intensity relative to F (ΔF/F) was plotted. For statistical analyses, the data were smoothed by calculating the moving average of a 10 s window, and the amount of time in which ΔF/F was higher than three was compared among strains and sexes.

For masculinization of SIA neurons, the him-5 strain carrying the integrated transgene was injected with ceh-17::fem-3 along with the injection marker unc-122::dsred (RRID:Addgene_8938). Both the animals with and without unc-122::dsred were tested.

Expression pattern of octopamine receptor genes.

The transcriptional reporter fusion gene octr-1::gfp was generated using the fusion PCR method (Hobert, 2002) with the primers fusionA (gtgtttttacgcaattcgcgc), fusionA* (cgaaccagtggtgtacgtag), fusionB (agtcgacctgcaggcatgcaagctgcagttaaggttccacattatgtg), fusionC (agcttgcatgcctgcaggtcgact), fusionD (aagggcccgtacggccgactagtagg), and fusionD* (ggaaacagttatgtttggtatattggg). The region corresponding to 3 kb upstream of the octr-1 gene was amplified with the primers fusionA and fusionB using genomic DNA as the template and was fused to 2–1876 of pPD95.75 (RRID:Addgene_1494). ser-3::gfp (Suo et al., 2006), ser-6::gfp (Yoshida et al., 2014), or octr-1::gfp was injected into him-5(e1490) animals together with ceh-17::dsred and the transformation marker pRF4, which contains the dominant roller mutation rol-6(su1006) (Kramer et al., 1990). Images of transformants were obtained with a confocal laser microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss).

Mate-searching behavior and food-leaving assay.

Mate-searching behavior was analyzed as previously described (Lipton et al., 2004). Animals were individually placed in the center of a bacterial lawn (9 mm diameter). The track left by animals was observed after 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h. If the animal reached 5 mm away from the edge of the Petri dish, the animal was considered to have left the lawn and dispersed.

To analyze food-leaving by video recording, molten low peptone NGM agar was poured into 24-well plates (500 μl per well). After solidification and drying, 5 μl of the OP50 suspension was placed at the center of the wells. The plates were incubated at 22°C overnight. Approximately 30 L4 animals were placed onto NGM plates, and the plates were cultured for ∼20 h. Animals were individually placed into the wells 30 min before recording and were recorded for 1 h, using the same equipment that was used for recording locomotor behavior. Using ImageJ, the edges of bacteria lawns were detected. The region was enlarged by approximately one worm length. The animal was considered to have left the bacterial lawn unless the entire body of the animal was inside of this region. Using R, the number of leaving events per 1 h in which animals stayed in the lawn was calculated.

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

Numbers of animals tested for each experiment are shown in the figures. Statistical analysis was performed using R. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to determine the p values. The Bonferroni correction was used for comparisons of more than two groups. For comparisons of behavioral states, percentage dwelling was compared between strains and sexes unless otherwise noted. For mate-searching behavior, the strains were contrasted by fitting the censored data with an exponential parametric survival model using maximum likelihood. The p values for Figs. 3–5, 10 are listed in Fig. 3-1, Fig. 4-1, Fig. 5-1, Fig. 10-1.

Figure 3.

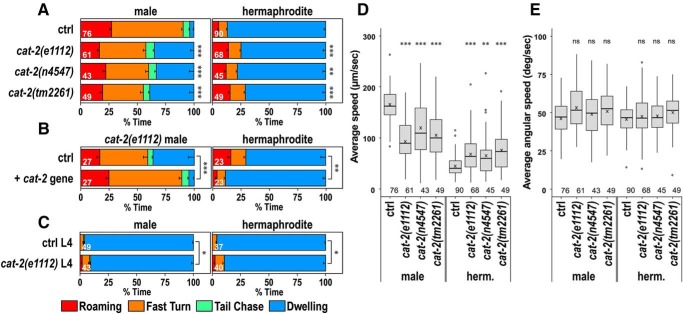

cat-2 is required for the regulation of behavioral states. A, Time spent in each behavioral class for males (left) and hermaphrodites (right) of control and cat-2(e1112), cat-2(n4547), and cat-2(tm2261) mutant animals. B, Time spent in each behavioral class for cat-2(e1112) mutants carrying (+ cat-2 gene) and not carrying (ctrl) the WT cat-2 gene. C, Time spent in each behavioral class for L4 males and L4 hermaphrodites of control and cat-2(e1112) mutant animals. Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Average speed (D) and average angular speed (E) during 900 s recording were determined for control and the cat-2 mutant animals. Boxes represent the lower and upper quartile values. Middle lines indicate the medians. Crosses represent the means. Whiskers represent the most extreme values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Circles represent outliers. Numbers in the graph indicate the numbers of animals tested. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. p values are listed in Figure 3-1.

Figure 5.

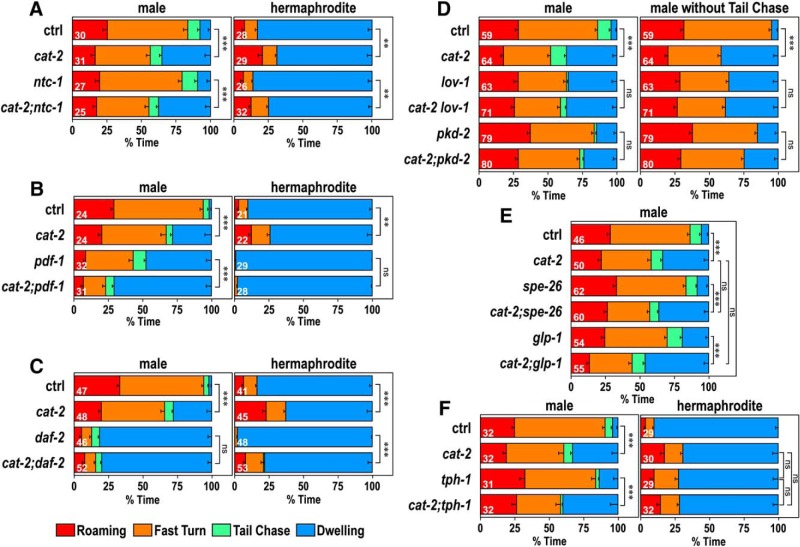

Interaction of cat-2 with other genetic factors. Time spent in each behavioral class for males (left) and hermaphrodites (right, except for D and E) of control and cat-2(e1112) mutant animals in the following mutant background: the oxytocin/vasopressin-related peptide mutant, ntc-1(tm2385) (A); the pigment-dispersing factor mutant, pdf-1(tm1996) (B); the insulin/IGF receptor mutant, daf-2(e1370) (C); the polycystic kidney disease-related gene mutants, lov-1(sy582) and pkd-2(sy606) (D); sperm-deficient mutants, spe-26(hc138) and glp-1(bn18) (E); and the serotonin-deficient mutant, tph-1(mg280) (F). Because the lov-1(sy582) and pkd-2(sy606) mutants have a defect in tail sensation and therefore have reduced tail chase, time spent in roaming, fast turn, and dwelling was compared after removing tail chase (D, right). Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. p values are listed in Figure 5-1.

Results

Sex differences in behavioral states

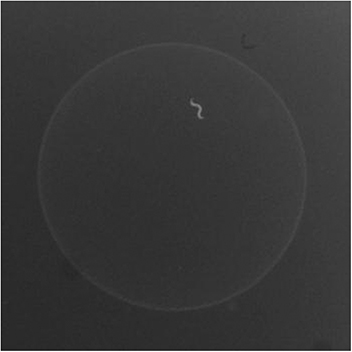

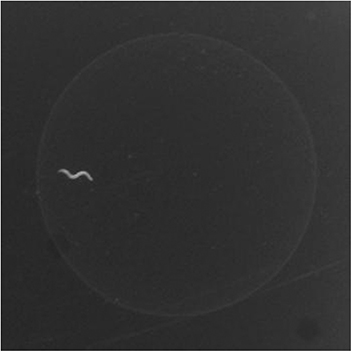

To analyze the locomotor behavior of males and hermaphrodites, CB4088 him-5 animals were individually placed on a small lawn of Escherichia coli OP50 and their movement was recorded (Fig. 1A,B; Movies 1, 2). As previously reported (Ben Arous et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2013), speed for hermaphrodites was relatively low for the majority of the time when they are in a bacterial lawn. In contrast, males rarely exhibited periods of low locomotor activity and spent most of their time moving at a relatively high speed. Males sometimes exhibited tail-chasing behavior (Wang et al., 2014) in which their tails are in contact with their own heads and they move in a backward circle, staying nearly at the same location (Movie 3). This behavior is believed to be an erroneous attempt to mate themselves as they curl their tails similarly to males mating with hermaphrodites. Animals exhibiting tail-chasing behavior had high circularity and low speed of the centroid.

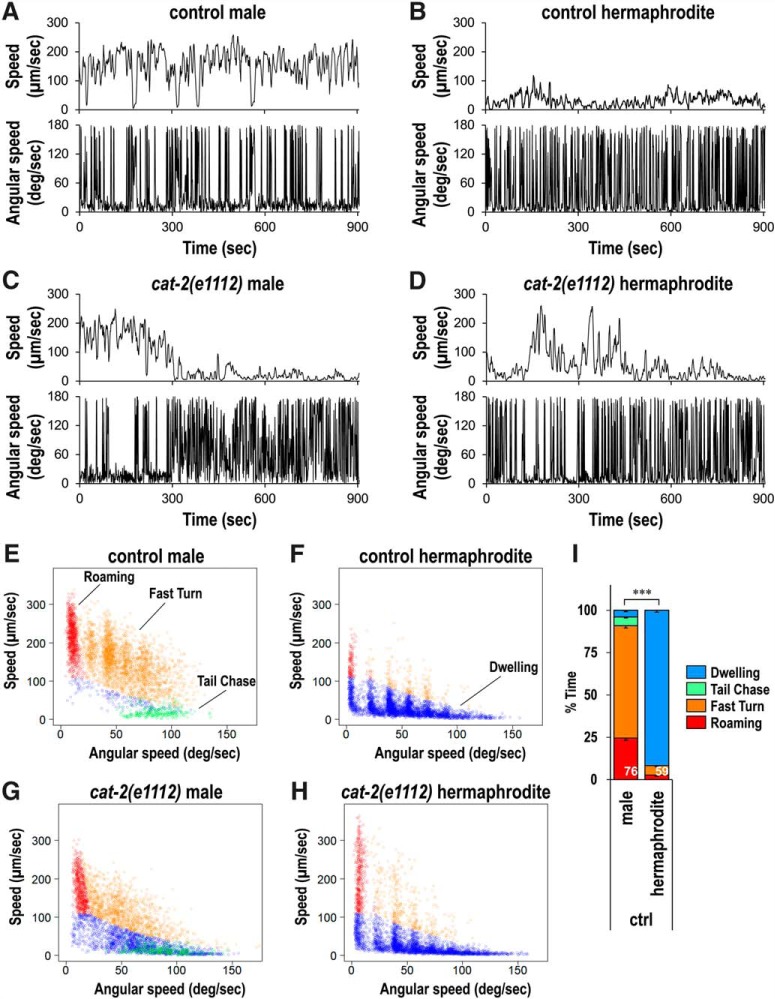

Figure 1.

Sex differences in the locomotion of C. elegans males and hermaphrodites. Locomotor speed (5 s moving average, top panels) and angular speed (bottom panels) of a him-5(e1490) male (A), him-5(e1490) hermaphrodite (B), cat-2(e1112);him-5(e1490) male (C), and cat-2(e1112);him-5(e1490) hermaphrodite (D) during 900 s recordings. Scatter plots of average speed and average angular speed in 10 s intervals for 50 each of the following: him-5(e1490) males (E), him-5(e1490) hermaphrodites (F), cat-2(e1112);him-5(e1490) males (G), and cat-2(e1112);him-5(e1490) hermaphrodites (H). Data points were categorized into four classes by circularity and cluster analysis (Figure 1-1) and shown in different colors: roaming, fast movement and low frequency of turning (red); fast turn, fast movement and high frequency of turning (orange); tail chase, tail-chasing behavior (green); and dwelling, slow movement (blue). I, The percentage of time spent exhibiting each behavioral class for him-5(e1490) mutants was determined. Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test: ***p < 0.001, between males and hermaphrodites for all of the behavioral classes. Dwelling: W = 0, p < 2.22 × 10−16. Tail chase: W = 4041.5, p < 2.22 × 10−16. Fast turn: W = 4483, p < 2.22 × 10−16. Roaming: W = 4329.5, p < 2.22 × 10−16.

Categorization of behavioral classes. Scatter plots of average speed and average angular speed in 10-sec intervals for 50 each of him-5(e1490) males (A) and him-5(e1490) hermaphrodites (B). Data points from animals exhibiting tail-chasing behavior (circularity > 0.7) were categorized as Tail Chase and are shown in green. Data points from males and hermaphrodites were combined (C) and subjected to cluster and discriminant analysis using R package mclust to be separated into three classes (D): Roaming, fast movement and low frequency of turning (red); Fast Turn, fast movement and high frequency of turning (orange); and Dwelling, slow movement (blue). Download Figure 1-1, TIF file (1.4MB, tif)

Locomotor behavior of a control male. The movie is at 60 times speed.

Locomotor behavior of a control hermaphrodite. The movie is at 60 times speed.

Tail chasing behavior of a control male. The animal moves in a circle with its tail in contact with its own head. The movie is at 5 times speed.

To quantitatively analyze locomotor behavior, average speed and angular speed for 10 s windows were calculated as described previously (Ben Arous et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2013), and 10 s data points from 50 males and 50 hermaphrodites were plotted using the plane of speed and angular speed (Fig. 1E,F). Most of the data points for hermaphrodites, as previously reported (Ben Arous et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2013), were seen in the area with low speed and high angular speed corresponding to the dwelling state, and a small number of the data points were seen in the area with relatively high speed and low angular speed, corresponding to the roaming state (Fig. 1F). In contrast, a high number of data points for males was seen in the area with high speed and low angular speed (Fig. 1E). In addition, many data points for males were observed in the high speed and high angular speed area, where few points were observed for hermaphrodites. A small number of points were also observed in the low speed and high angular speed area in males. However, these data points are qualitatively different from points from the dwelling hermaphrodites in that these are mostly with average circularity > 0.7, corresponding to animals exhibiting tail-chasing behavior.

In the previous studies, behavioral states were categorized by drawing a straight line in the speed-angular speed plane to separate roaming and dwelling (Ben Arous et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2013). However, such a straight line would not be suitable in categorizing males as they seem to have a different class of behavior in which both speed and angular speed are high. Through cluster analysis using the R package mclust (Scrucca et al., 2016) (Fig. 1-1), the data points were categorized into the following three behavioral classes: dwelling (slow movement), roaming (fast movement and low frequency of turning), and fast turn (fast movement and high frequency of turning). Data points with 10 s average circularity > 0.7 were categorized into a separated class: tail chase. Then the percentage of time spent in each class was calculated (Fig. 1I). To validate this behavioral categorization, we manually analyzed 10 males and 10 hermaphrodites and found that the results of the manual and automatic categorization had strong correlations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation between manual and automatic scoringa

| Male | Hermaphrodite | |

|---|---|---|

| Roaming | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Fast turn | 0.94 | 0.59 |

| Dwelling | 0.90 | 0.92 |

| Tail chase | 0.91 | NA |

aCorrelation coefficients for percent time spent with each class determined by manual and automatic scoring.

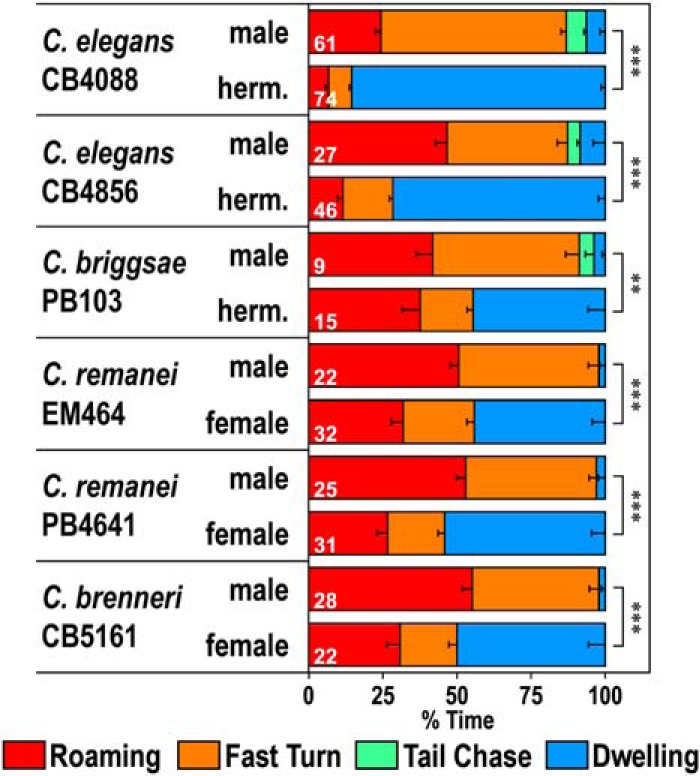

There were large differences in time allocation for each behavioral class when comparing males and hermaphrodites (Fig. 1I). The percentage time spent in dwelling was significantly higher in hermaphrodites than in males. On the other hand, there was more time spent in the roaming, fast turn, and tail chase classes for males. These results suggest that there is a sex difference in the regulation of behavioral states. We also tested another wild isolate of C. elegans, CB4856, and other Caenorhabditis species, including the androdioecious (male-hermaphrodite) species, C. briggsae, and the dioecious (male-female) species, C. remanei and C. brenneri, and found that there are sex differences in the distribution of time spent in different behavioral classes in all strains tested (Fig. 2). These results suggest that sex differences in the distribution of behavioral states are not specific to C. elegans but are observed in other nematode species, including male-female species.

Figure 2.

Locomotor behavior of other Caenorhabditis species. Time spent in each behavioral class for the N2 background C. elegans him-5 strain CB4088, C. elegans Hawaiian isolate CB4856, C. briggsae him strain PB103, C. remanei strains EM464 and PB4641, and C. brenneri strain CB5161. C. elegans and C. briggsae are androdioecious (male-hermaphrodite), whereas C. remanei and C. brenneri are dioecious (male-female). Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. ***p < 0.001 (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction). **p < 0.01 (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction). CB4088: W = 72.5, p < 2.22 × 10−16. CB4856: W = 49, p = 3.58 × 10−9. PB103: W = 2, p = 0.00699. EM464: W = 23, p = 1.66 × 10−7. PB4641: W = 20, p = 2.39 × 10−8. CB5161: W = 10, p = 8.00 × 10−8.

Dopamine regulates behavioral states in a sexually dimorphic manner

The cat-2 gene in C. elegans encodes tyrosine hydroxylase that is the rate-limiting enzyme for dopamine synthesis (Lints and Emmons, 1999). In hermaphrodites, dopamine regulates many aspects of behavior, including locomotion, turning frequency, and learning (Chase and Koelle, 2007). Furthermore, dopamine regulates mating behavior in males, and cat-2 mutants have defects in vulva location, spicule insertion, and ejaculation and have reduced postcoital lethargy (Correa et al., 2012, 2015; LeBoeuf et al., 2014). We recorded the locomotor behavior of cat-2 mutants and found that cat-2 mutant males sometimes exhibited an extended period of time where their speed was low, which was rarely seen in WT background males (Fig. 1C,G; Movie 4). The percentage of dwelling was significantly increased in the three different mutants of cat-2, including e1112, n4547, and tm2261 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, cat-2 mutant hermaphrodites had more time with high locomotor activity than WT hermaphrodites (Fig. 1D,H; Movie 5). Correspondingly, the percentage of dwelling was significantly decreased in the hermaphrodites of cat-2 mutants (Fig. 3A). This result is consistent with recent studies reporting that the dwelling state is decreased in cat-2 hermaphrodites (Stern et al., 2017; Oranth et al., 2018). The average speed of cat-2 mutants was also decreased in males and increased in hermaphrodites compared with control animals (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the average angular speed of cat-2 mutants was not changed in either males or hermaphrodites (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that cat-2 modulates behavioral states primarily through affecting locomotor speed. To confirm the involvement of the cat-2 gene in this regulation, cat-2 mutants carrying the WT cat-2 gene were examined (Fig. 3B). The percentage of dwelling was reduced in males carrying the cat-2 gene, whereas the percentage of dwelling was increased in hermaphrodites carrying the cat-2 gene compared with control animals that do not carry the cat-2 gene. This shows that the introduction of the cat-2 gene rescues both males and hermaphrodites of cat-2 mutants. Together, these results suggest that dopamine decreases the low locomotor activity state in males and increases the low locomotor activity state in hermaphrodites.

Locomotor behavior of a cat-2(e1112) mutant male. The movie is at 60 times speed.

List of p values. Download Figure 3-1, DOCX file (14.1KB, docx)

Locomotor behavior of a cat-2(e1112) mutant hermaphrodite. The movie is at 60 times speed.

C. elegans animals transition through four larval stages before becoming sexually mature adults. The locomotor behavior of animals in the L4 stage was examined (Fig. 3C). Both the males and hermaphrodites of L4 animals spent most of the time in dwelling. The cat-2 mutation reduced the percentage of dwelling in both L4 males and hermaphrodites. This result suggests that, in L4 males, dopamine increases the inactive dwelling state similarly to adult hermaphrodites and that dopamine-mediated reduction of the dwelling state only occurs in mature males.

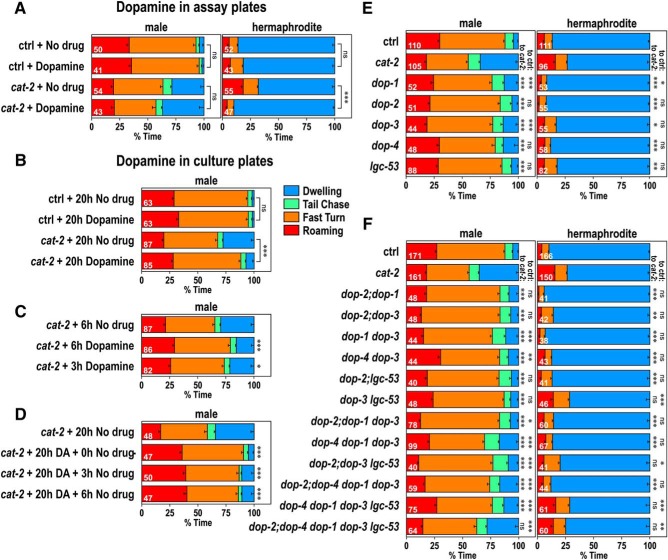

Exogenous dopamine rescues cat-2 phenotypes

cat-2 mutants were supplemented with exogenous dopamine to examine whether it suppresses their locomotor phenotypes. First, dopamine was added to assay plates where their behavior was recorded (Fig. 4A). This exogenous dopamine treatment suppressed the cat-2 phenotype of hermaphrodites, causing an increase in the percentage of dwelling of cat-2 hermaphrodites. However, exogenous dopamine in the assay plates had little effect on cat-2 males. Next, dopamine was added to culture plates where L4 animals were placed a day before recording and cultured for 20 h (Fig. 4B). Dopamine in the culture plates significantly reduced percentage of dwelling of cat-2 males. Because animals were exposed to dopamine since they were at the L4 stage, dopamine may be required for the development of males. To address this, animals were grown on plates without dopamine for 20 h beginning from the L4 stage, followed by exposure to dopamine for 3 or 6 h (Fig. 4C). Six or 3 h dopamine exposure significantly reduced the percentage of dwelling, suggesting that a few hours of dopamine exposure after development is required. In the experiments in Figure 4B, dopamine was not included in the assay plates, but the effect of dopamine exposure was observed. Moreover, the effects of dopamine persisted for at least 6 h after its removal (Fig. 4D). Together, these results suggest that, in males, dopamine is not required at the time of recording for increased locomotor activity but is required before recording. On the other hand, in hermaphrodites, dopamine present at the time of recording is sufficient for suppression of locomotor activity.

Figure 4.

Dopamine regulates behavioral states through different mechanisms in males and hermaphrodites. A, Dopamine was added to assay plates in which behavior was recorded, and time spent in each behavioral class was determined for males (left) and hermaphrodites (right) of control and cat-2(e1112) animals. B, Dopamine was added to plates where control and cat-2(e1112) males were grown for 20 h from the L4 stage. C, cat-2(e1112) mutants were exposed to dopamine from 3 or 6 h before transferring to assay plates, and time spent in each behavioral class was determined. D, cat-2(e1112) mutants were exposed to dopamine for 20 h and transferred to plates without dopamine for 3 or 6 h before transferring to assay plates. Dopamine was not added to assay plates for the experiments in B–D. E, F, Time spent in each behavioral class for control animals and dopamine receptor mutants, dop-1(vs101), dop-2(vs105), dop-3(vs106), dop-4(tm1392), and lgc-53(tm2735). Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. p values are listed in Figure 4-1.

List of p values. Download Figure 4-1, DOCX file (17.6KB, docx)

We next determined which dopamine receptors function in the regulation of the behavioral states. There are five dopamine receptors identified in C. elegans: the D1-like receptor, DOP-1 (Suo et al., 2002); the D2-like receptors, DOP-2 (Suo et al., 2003) and DOP-3 (Sugiura et al., 2005); the Gq-coupled receptor, DOP-4 (Sugiura et al., 2005); and the dopamine-gated Cl- channel, LGC-53 (Ringstad et al., 2009). We tested all of the single receptor mutants as well as some combined mutants (Fig. 4E,F). In males, only when all five dopamine receptors were mutated, the percentage of dwelling was not significantly different from that of cat-2 mutants. This result suggests that all of the known dopamine receptors play a role in increasing locomotor activity in males. For hermaphrodites, the percentage of dwelling was not different from cat-2 mutants in all the strains that carried mutations in both dop-3 and lgc-53, suggesting that dop-3 and lgc-53 are required for decreasing the locomotor activity in hermaphrodites. Together, these results illustrate that dopamine regulates behavioral states through different mechanisms in males and hermaphrodites.

Dopamine and the polycystic kidney disease genes act in the same pathway in males

We examined the interaction between cat-2 and genes that are known to regulate aspects of male behavior. The ntc-1 gene encodes a vasopressin/oxytocin-related peptide, and ntc-1 mutants are impaired in mate-searching behavior and mating (Garrison et al., 2012). The ntc-1 mutation alone did not impact the percentage of dwelling in either males or hermaphrodites (Fig. 5A). The cat-2 mutation did alter locomotor behavior of both males and hermaphrodites in the ntc-1 mutant background, suggesting that ntc-1 has little effect on regulation by cat-2. Pigment-dispersing factor mutants (pdf-1) exhibit reduced mate-searching behavior in males and an increased dwelling state in hermaphrodites (Barrios et al., 2012; Flavell et al., 2013). The pdf-1 mutation alone increased dwelling in males and hermaphrodites (Fig. 5B). The effect of cat-2 was present in pdf-1 males and was not clear in hermaphrodites as locomotor activity was very low in pdf-1 hermaphrodites. Therefore, the results suggest that pdf-1 reduces dwelling both in males and hermaphrodites and that pdf-1 and cat-2 act in parallel pathways in males.

List of p values. Download Figure 5-1, DOCX file (14.9KB, docx)

We next investigated the daf-2 gene, which encodes the insulin/IGF receptor, as daf-2 mutants exhibit reduced mate-searching behavior (Lipton et al., 2004). The percentage of dwelling was increased in daf-2 mutant males, and it was not further increased by cat-2 in cat-2;daf-2 double mutants (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that, in males, daf-2 and cat-2 act in the same pathway to reduce dwelling and that daf-2 acts downstream of cat-2. However, given that the daf-2 phenotype is so strong and could mask the milder cat-2 phenotype, it is also possible that cat-2 and daf-2 act in parallel pathways. The percentage of dwelling was also increased by daf-2 in hermaphrodites (Fig. 5C). However, cat-2 decreased percentage of dwelling in the daf-2 background hermaphrodites. This result suggests that, in hermaphrodites, daf-2 and cat-2 have opposite effects on dwelling and act in parallel pathways.

The polycystic kidney disease-related genes lov-1 and pkd-2 are required for normal male mating behavior as well as mate-searching behavior, and these two genes work in the same pathway (Barr and Sternberg, 1999; Barr et al., 2001; Barrios et al., 2008). lov-1 and pkd-2 are expressed exclusively in male-specific sensory neurons and are required for functions of these neurons. The percentage of dwelling of cat-2;lov-1 and cat-2;pkd-2 double mutants was not significantly different from that of lov-1 and pkd-2, respectively (Fig. 5D, left). lov-1 and pkd-2 mutants had reduced tail chase presumably because of their defects in tail sensation. Even when percentage of dwelling was calculated after removing tail chase (Fig. 5D, right), the percentage of dwelling of cat-2;lov-1 and cat-2;pkd-2 double mutants was not significantly different from that of lov-1 and pkd-2, respectively. The results suggest that the polycystic kidney disease genes and cat-2 act in the same pathway in males. Therefore, the dopaminergic pathway for behavioral state regulation likely involves the male sensory neurons. spe-26 and glp-1 mutants have reduced sperm production and exhibit reduced mate-searching behavior (Priess et al., 1987; Varkey et al., 1995; Lipton et al., 2004). The cat-2 mutation increased the percentage of dwelling in the spe-26 and glp-1 backgrounds, and the percentage of dwelling of cat-2 mutants and those of cat-2;spe-26 or cat-2;glp-1 double mutants were not significantly different (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that sperm content does not affect the dopaminergic regulation of locomotor behavior.

Serotonin and dopamine work through the same pathway

The tph-1 gene encodes tryptophan hydroxylase, which is required for serotonin production (Sze et al., 2000). We examined the locomotor behavior of tph-1 mutants and tph-1;cat-2 double mutants (Fig. 5F). The tph-1 mutation alone had little effect on the behavioral states in males and did not affect regulation by cat-2 in males. In hermaphrodites, it was previously reported that serotonin increases the dwelling state (Flavell et al., 2013). The percentage of dwelling in tph-1 mutant hermaphrodites was reduced to a level that was not different from that of cat-2 mutants. Furthermore, cat-2;tph-1 double mutants showed no further decrease in percentage of dwelling from that of single mutants. These results suggest that dopamine and serotonin regulate locomotor behavior through the same pathway in hermaphrodites.

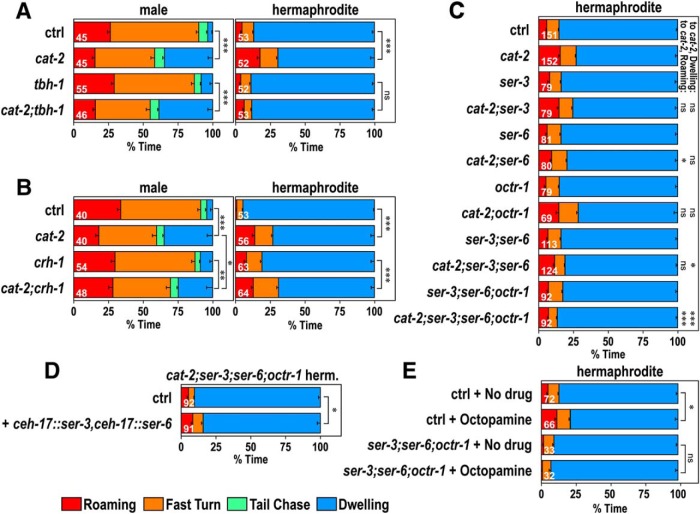

Octopamine signaling in the SIA neurons works downstream of dopamine

It was previously reported that dopamine suppresses octopamine signaling in hermaphrodites and that octopamine signaling activated in the absence of dopamine signaling induces signal transduction in the SIA neurons, leading to activation of CREB (Suo et al., 2006, 2009). Furthermore, octopamine is involved in experience-dependent changes in the sex-specific pruning of synaptic connections (Bayer and Hobert, 2018). We examined octopamine-deficient tbh-1 mutants and found that tbh-1 had little effect on males (Fig. 6A). In hermaphrodites, tbh-1 suppressed cat-2 and the percentage of dwelling was not significantly different between tbh-1 and cat-2;tbh-1, suggesting that octopamine signaling works downstream of dopamine.

Figure 6.

Octopamine works downstream of dopamine. A, Time spent in each behavioral class for males (left) and hermaphrodites (right) of control and cat-2(e1112) mutant animals in the octopamine-deficient tbh-1(ok1196) mutant background. B, Time spent in each behavioral class for control and cat-2(e1112) mutant animals in the mutant background of the CREB homolog, crh-1(tz2). C, Time spent in each behavioral class for control and cat-2(e1112) mutant hermaphrodites in the octopamine receptor mutant background, ser-3(ad1774), ser-6(tm2104), and octr-1(ok371). D, Time spent in each behavioral class for cat-2(e1112);ser-3(ad1774);ser-6(tm2104);octr-1(ok371) mutants carrying (+ ceh-17::ser-3,ceh-17::ser-6) and not carrying (ctrl) the plasmids that induce expression of ser-3 and ser-6 in the SIA neurons. E, Octopamine was added to assay plates in which behavior was recorded, and time spent in each behavioral class was determined for hermaphrodites of control and ser-3(ad1774);ser-6(tm2104);octr-1(ok371) mutant animals. Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. p values are listed in Figure 6-1.

List of p values. Download Figure 6-1, DOCX file (14.2KB, docx)

We also examined the effect of the crh-1 gene, which encodes the CREB homolog (Fig. 6B). Although crh-1 hermaphrodites exhibited a small decrease in the percentage of dwelling, the cat-2 mutation further decreased it in the crh-1 background, suggesting that crh-1 does not suppress cat-2 for the regulation of behavioral states. In males, the percentage of dwelling of cat-2;crh-1 was slightly smaller than that of cat-2, suggesting that CREB plays a role in regulation of behavioral states by dopamine in males.

There are three octopamine receptors in C. elegans: the Gq-coupled receptors, SER-3 (Suo et al., 2006) and SER-6 (Mills et al., 2012), and the Gi-coupled receptor, OCTR-1 (Wragg et al., 2007). We next examined whether the mutations in these receptors suppress the effects of cat-2 in hermaphrodites (Fig. 6C). The percentage of dwelling of cat-2 mutants was not significantly affected by the ser-3, ser-6, or octr-1 single mutations. Through the examination of double and triple mutants, we found that cat-2;ser-3;ser-6 and cat-2;ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 mutants had a significantly larger percentage of dwelling than cat-2 mutants. These results suggest that both ser-3 and ser-6 work downstream of dopamine. The results did not exclude the possibility that octr-1 is also involved in the regulation because the time spent exhibiting roaming of cat-2;ser-3;ser-6 was not significantly different from cat-2, and it was only in the cat-2;ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 mutants that the amounts of time spent exhibiting both dwelling and roaming were significantly different from those of cat-2.

Churgin et al. (2017) showed that octopamine signaling works downstream of serotonin in the regulation of the behavioral states of hermaphrodites and that SER-3 and SER-6 work within the SIA neurons in this regulation. To examine whether the SIA neurons are also involved in the regulation of behavioral states by dopamine, we expressed SER-3 and SER-6 in the SIA neurons of the cat-2;ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 mutants using the ceh-17 promotor, which induces gene expression only in the SIA neurons and one additional neuron (Pujol et al., 2000). The mutants expressing SER-3 and SER-6 in the SIA neurons exhibited reduced percentage of dwelling compared with ones without expression of SER-3 and SER-6 (Fig. 6D), suggesting that, in hermaphrodites, it is also the SIA neurons in which octopamine signaling is working downstream of dopamine. However, given that the reduction of percentage of dwelling was small, the receptors may also work in other neurons.

If octopamine signaling is activated in the SIA neurons in the absence of dopamine in cat-2 mutants and this reduces the dwelling state, exogenous application of octopamine in WT animals should reduce the inactive state. Incorporation of octopamine in the assay plates reduced percentage of dwelling in WT background animals (Fig. 6E). Reduction in the percentage of dwelling was not observed in ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 triple mutants. Together, the above results suggest that octopamine signaling, which is activated in the absence of dopamine, reduces the inactive state of hermaphrodites.

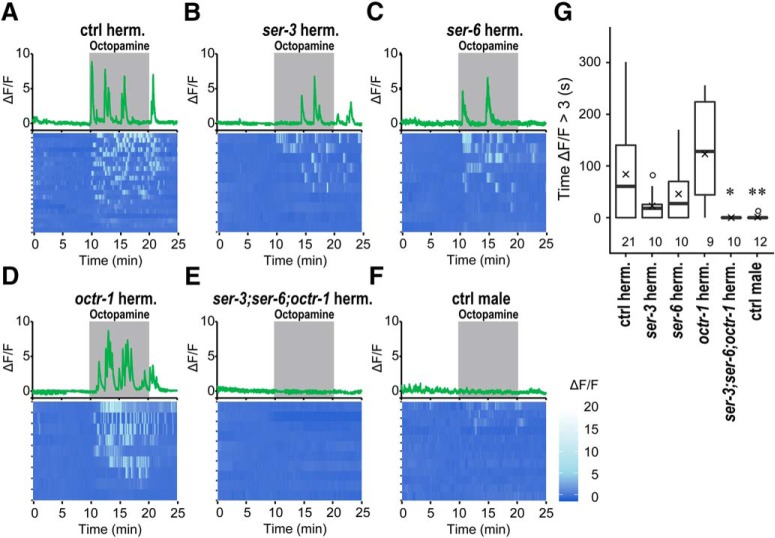

Octopamine induces a calcium response in the SIA neurons of hermaphrodites but not males

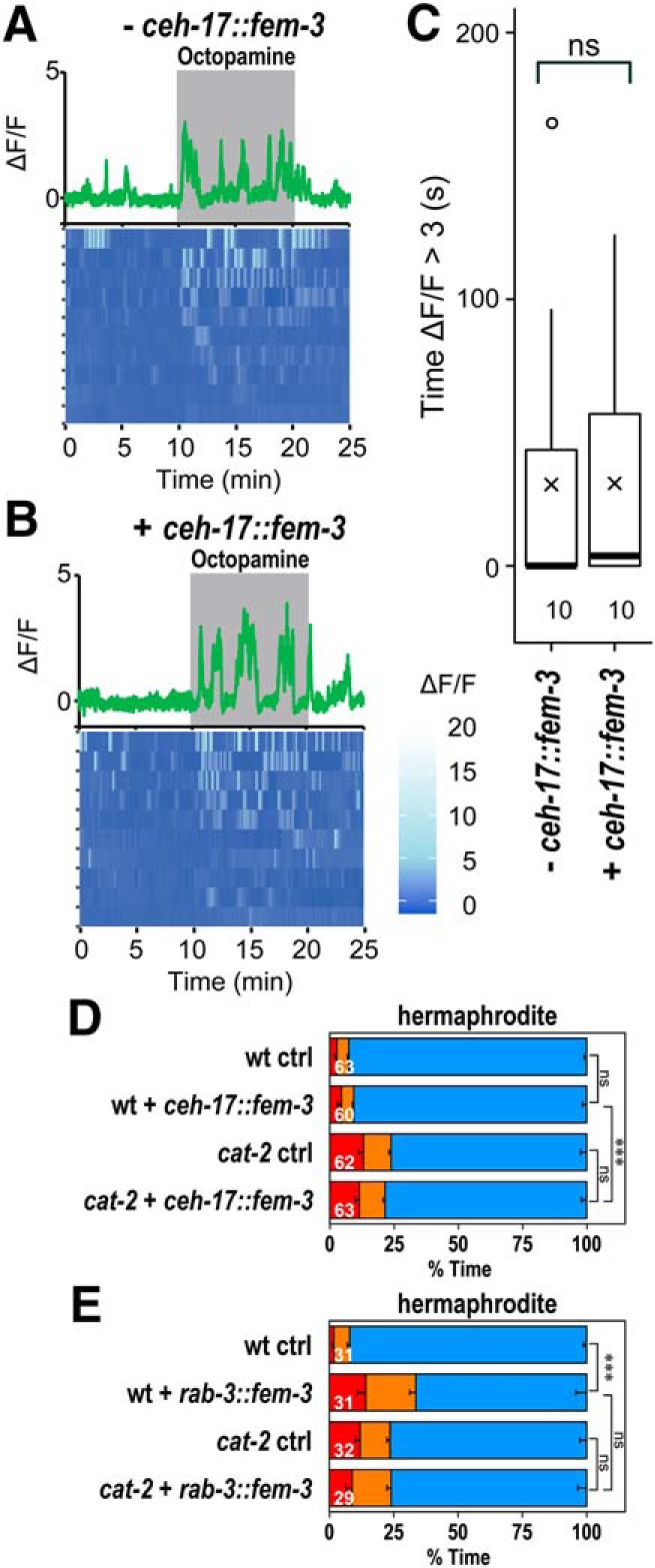

The SIA neurons are sex-shared neurons and exist not only in hermaphrodites but also in males (Sulston et al., 1980; White et al., 1986). However, the reduction of percentage of dwelling by the cat-2 mutation is observed in hermaphrodites but not in males. To address whether there is a difference in the responsiveness to octopamine between the SIA neurons of males and those of hermaphrodites, calcium imaging of SIA neurons was performed by expressing GCaMP6 (Ohkura et al., 2012) in the SIA neurons using the ceh-17 promotor. Animals were placed in the olfactory chip (Chronis et al., 2007) and exposed to octopamine-containing buffer. In the WT background hermaphrodites, calcium oscillation was evoked upon octopamine exposure (Fig. 7A). Although there were varying degrees of calcium responses in the ser-3, ser-6, and octr-1 single mutants, there was essentially no response in ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 triple mutants (Fig. 7B–E,G). In WT males, the calcium response to octopamine was significantly reduced compared with WT hermaphrodites (Fig. 7F,G). The observation that calcium response is evoked by octopamine in the SIA neurons in hermaphrodites but there was little response evoked in males suggests that there is a sex difference in responsiveness to octopamine in the SIA neurons.

Figure 7.

Calcium response of the SIA neurons upon octopamine treatment. Calcium imaging of control (A), ser-3(ad1774) (B), ser-6(tm2104) (C), octr-1(ok371) (D), and ser-3(ad1774);ser-6(tm2104);octr-1(ok371) (E) background hermaphrodites and WT males (F) expressing GCaMP6 in the SIA neurons. Top panels, Representative graphs of fluorescence change recorded from a single animal. Shaded areas represent the presence of octopamine. Bottom panels, Heatmap graphs of fluorescence change with each row representing individual animals. G, Length of time in which ΔF/F was >3. Boxes represent the lower and upper quartile values. Middle lines indicate the medians. Crosses represent the means. Whiskers represent the most extreme values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Circles represent outliers. Numbers in the graph indicate the numbers of animals tested. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. ser-3 hermaphrodites: W = 141, p = 1.00. ser-6 hermaphrodites: W = 127, p = 1.00. octr-1 hermaphrodites: W = 73, p = 1.00. ser-3;ser-6;octr-1 hermaphrodites: W = 180, p = 0.0105. Control males: W = 212, p = 0.00863.

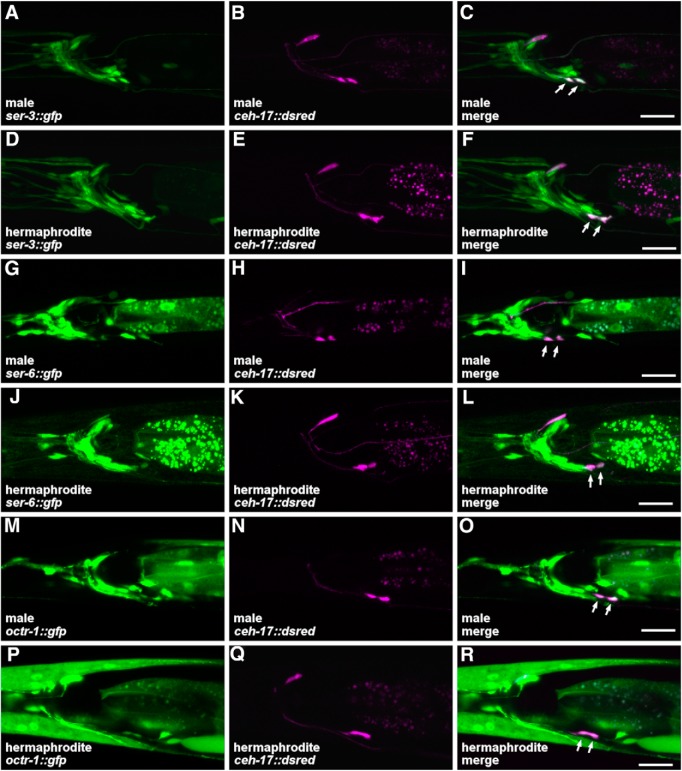

We next examined expression of the octopamine receptor genes in the SIA neurons using transcriptional fusion genes (Fig. 8). As previously reported (Suo et al., 2006; Yoshida et al., 2014), ser-3 and ser-6 were expressed in a number of neurons, including the SIA neurons in hermaphrodites. octr-1 was also expressed in the SIA neurons of hermaphrodites. Furthermore, expression of ser-3, ser-6, and octr-1 in the SIA neurons was similarly observed in males. These results suggest that, at least at the transcription level, expression of the octopamine receptors in the SIA neurons is not different between males and hermaphrodites; therefore, the sex difference in the octopamine response is unlikely caused by altered receptor expression.

Figure 8.

Expression of the octopamine receptor genes in SIA neurons. The GFP and DsRed fluorescent images and the merged images were obtained from him-5(e1490) animals carrying ser-3::gfp (A–C, male; D–F, hermaphrodite), ser-6::gfp (G–I, male; J–L, hermaphrodite), or octr-1::gfp (M–O, male; P–R, hermaphrodite). The animals also carried ceh-17::dsred, which labels SIA neurons with DsRed. Arrows indicate SIA neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm.

In hermaphrodites, the overexpression of the sex determination gene fem-3 from the pan-neural rab-3 promoter results in masculinization of the shared neurons mostly without producing male-specific neurons (Lee and Portman, 2007; White et al., 2007). Furthermore, subsets of neurons can be masculinized by expression of fem-3 using cell-specific promotors. To examine whether the sex difference in responsiveness to octopamine arise from the sex of the SIA neurons, calcium imaging was performed in hermaphrodites carrying ceh-17::fem-3, which would express fem-3 in the SIA neurons (Fig. 9A–C). Although the transgenic strain appeared somewhat unhealthy, both animals carrying and not carrying ceh-17::fem-3 similarly responded to octopamine in the SIA neurons, unlike what was seen for WT background males. This result suggests that the sexual dimorphism in SIA signaling does not arise from the sex of the SIA neurons and implies that it is a result of a network effect.

Figure 9.

Masculinization of the SIA neurons. A, B, Calcium imaging of hermaphrodites not carrying (− ceh-17::fem-3) and carrying ceh-17::fem-3 (+ ceh-17::fem-3). Top, Representative graphs of fluorescence change recorded from a single animal. Shaded areas represent the presence of octopamine. Bottom, Heatmap graphs of fluorescence change with each row representing individual animals. C, Length of time in which ΔF/F was >3. Boxes represent the lower and upper quartile values. Middle lines indicate the medians. Crosses represent the means. Whiskers represent the most extreme values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Circles represent outliers. Numbers in the graph indicate the numbers of animals tested. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test: ns, not significant, W = 56.5, p = 0.609. D, Time spent in each behavioral class for WT and cat-2(e1112) background hermaphrodites carrying (+ ceh-17::fem-3) and not carrying (ctrl) ceh-17::fem-3. E, Time spent in each behavioral class for WT and cat-2(e1112) background hermaphrodites carrying (+ rab-3::fem-3) and not carrying (ctrl) rab-3::fem-3. Numbers in the bars indicate the numbers of animals tested. Error bars indicate SEM. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. wt ctrl versus wt + ceh-17::fem-3: W = 1962.5, p = 1.00. cat-2 ctrl versus cat-2 + ceh-17::fem-3: W = 1831.5, p = 1.00. wt + ceh-17::fem-3 versus cat-2 + ceh-17::fem-3: W = 2904.5, p = 1.72 × 10−6. wt ctrl versus wt + rab-3::fem-3: W = 816.5, p = 1.39 × 10−5. cat-2 ctrl versus cat-2 + rab-3::fem-3: W = 447, p = 1.00. wt + rab-3::fem-3 versus cat-2 + rab-3::fem-3: W = 341.5, p = 0.671.

We next examined the behavioral states of animals carrying ceh-17::fem-3 (Fig. 9D). WT background hermaphrodites carrying ceh-17::fem-3 had a normal level of percentage of dwelling. The percentage of dwelling was reduced in cat-2 mutants carrying ceh-17::fem-3, suggesting that dopamine alters locomotor activity, even when the SIA neurons of hermaphrodites were masculinized. Hermaphrodites carrying rab-3::fem-3, which masculinize all the shared neurons, were also tested (Fig. 9E). Hermaphrodites carrying rab-3::fem-3 exhibited reduced percentage of dwelling compared with the control animals. The percentage of dwelling was not further reduced in cat-2 mutants carrying rab-3::fem-3, suggesting that dopamine does not alter locomotor activity in the animals with masculinized shared neurons. Together, the results further suggest that the sexually dimorphic signaling is not intrinsic to the SIA neurons and that other shared neurons play roles in generating sex differences in bioamine signaling.

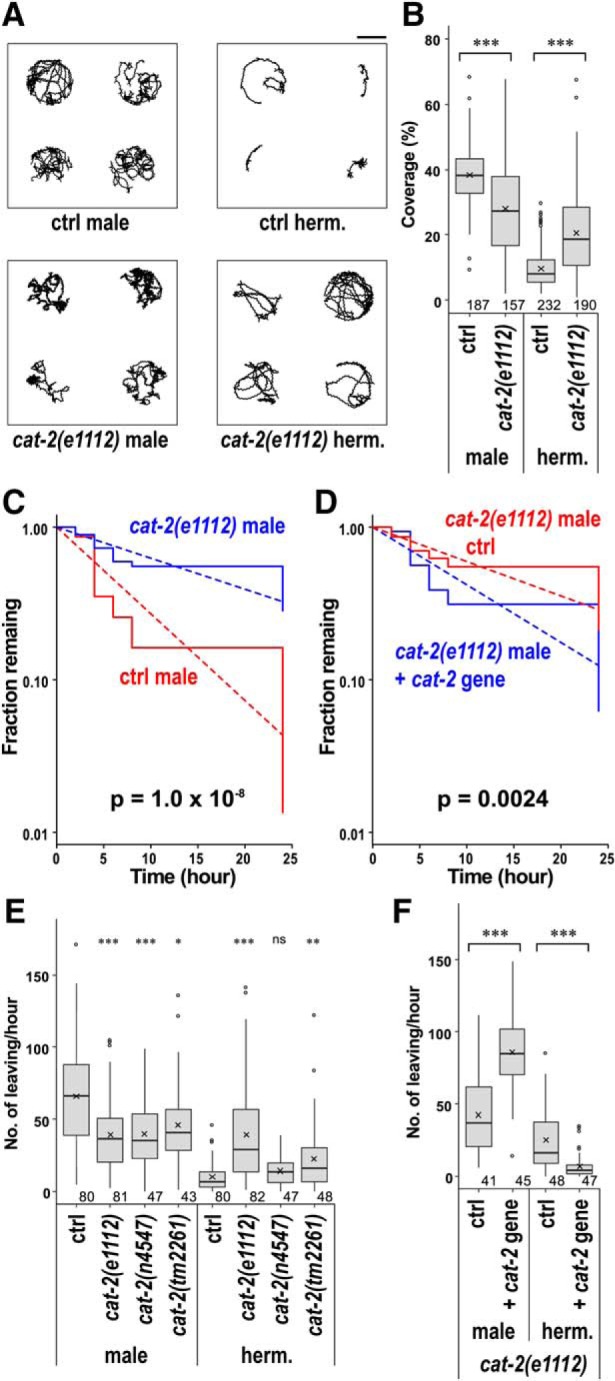

Sexually dimorphic regulation of exploration by dopamine

The results above suggested that dopamine increases the time spent in the high locomotor activity state in males. Animals with increased locomotor activity may be able to explore a larger area of a bacterial lawn, which would be beneficial for males who are in search of a mate. To examine whether indeed males explore a larger area of a lawn, the areas of the traces of animals were quantified and the percentage of the bacterial lawn covered by the trace was calculated (Fig. 10A,B). Males covered a much larger area than hermaphrodites. Area coverage was significantly reduced in cat-2 males compared with that in WT males, whereas cat-2 hermaphrodites covered a larger area than WT hermaphrodites. These results suggest that dopamine allows males to explore a larger area of the bacterial lawn and keeps hermaphrodites in a smaller area.

Figure 10.

Dopamine regulates exploration inside and outside of a bacterial lawn. Control and cat-2(e1112) animals were placed on bacterial lawns, and the behavior was recorded for 15 min. A, Representative traces left by animals. Four traces each are shown. Scale bar, 5 mm. B, The percentages of the lawn area covered by the traces of animals per 15 min are shown. C, Mate-searching behavior of control and cat-2(e1112) males. D, Mate-searching behavior of cat-2(e1112) males carrying (+ cat-2 gene) and not carrying (ctrl) the WT cat-2 gene. Fraction of animals that has not dispersed were plotted. The data were fitted to an exponential parametric survival model (dotted lines). E, Control and cat-2(e1112), cat-2(n4547), and cat-2(tm2261) mutant animals were placed on bacterial lawns and were recorded for 1 h. Numbers of times animals left the lawns per 1 h were determined. F, Numbers of times animals left the lawn per hour for cat-2(e1112) mutants carrying (+ cat-2 gene) and not carrying (ctrl) the WT cat-2 gene. Boxes represent the lower and upper quartile values. Middle lines indicate the medians. Crosses represent the means. Whiskers represent the most extreme values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Circles represent outliers. Numbers in the graphs indicate the numbers of animals tested. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant, p > 0.05. p values are listed in Figure 10-1.

List of p values. Download Figure 10-1, DOCX file (15.3KB, docx)

As part of mate-searching behavior, males often leave and disperse away from a bacterial lawn when there is no hermaphrodite present, whereas hermaphrodites leave the lawn less frequently (Lipton et al., 2004). Mate-searching behavior was analyzed by measuring the time it takes for a male to leave a small lawn and reach the edge of assay plates. cat-2 mutant males showed significantly less dispersal compared with WT males (Fig. 10C), which was at least partially rescued by introduction of the cat-2 gene (Fig. 10D), suggesting that dopamine promotes mate-searching. To further assess food-leaving behaviors of males and hermaphrodites, animals were individually placed on small bacterial lawns (5 mm diameter) and were video-recorded to determine how frequently they leave the lawns (Fig. 10E). WT males left lawns at a much higher rate than WT hermaphrodites. cat-2 mutant males left bacterial lawns at significantly lower rates than WT males. In contrast, cat-2(e1112) and cat-2(tm2261) hermaphrodites left lawns at higher rates than WT hermaphrodites. Both the reduced leaving in males and the increased leaving in hermaphrodites were suppressed by introduction of the WT cat-2 gene in the cat-2 mutants (Fig. 10F). The results suggest that dopamine promotes leaving in males and suppresses leaving in hermaphrodites and that dopamine regulates food-leaving in a sexually dimorphic manner.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the sex differences in the regulation of behavioral states and found that C. elegans males spend much more time than hermaphrodites in the high locomotor activity state, the roaming state. In addition to the roaming state, males spent much time exhibiting high-speed and high-turning frequency behaviors. In dopamine-deficient cat-2 mutants, the dwelling state was increased in males and decreased in hermaphrodites. This suggests that dopamine plays a major role in generating the sex differences in the behavioral states by having the opposite effects in males and hermaphrodites. Given that there remained some sex differences in the cat-2 mutants, dopamine does not account for all of the sex differences in the behavioral states. Therefore, other factors may be involved in generating these differences.

Dopamine plays a role in some aspects of male mating behavior, including postcoital lethargy where males become inactive after mating with hermaphrodites, ensuring that enough sperms are available for the next mating (LeBoeuf et al., 2014). Postcoital lethargy is not the cause of an increased dwelling state in cat-2 mutants because dopamine promotes postcoital lethargy. Moreover, in our experiments, males were grown separately from hermaphrodites and were prohibited from mating. cat-2 mutant males sometimes ejaculate outside of the vulva during mating because they have abnormal spicule protraction and vulva sensing (LeBoeuf et al., 2014). Although it is unknown whether cat-2 males ejaculate abnormally in the absence of hermaphrodites, it was possible that this affected their behavior, as males with reduced sperm quantity have reduced sex drive (Lipton et al., 2004). However, because sperm-deficient spe-26 and glp-1 mutants did not suppress cat-2 in the regulation of the behavioral states, it is unlikely that dopamine affects the states through changing the sperm level.

For the same neurotransmitter, dopamine, to regulate the same behavior in opposite directions in different sexes, there need to be two separate mechanisms of regulation: one for males and another for hermaphrodites. In addition, there should be mechanisms to inactivate male-specific regulation in hermaphrodites and vice versa. The mechanisms by which dopamine regulates behavioral states in males and hermaphrodites should be distinct because the timing for dopamine requirement is different. In hermaphrodites, exogenous dopamine had an immediate effect on the behavior of cat-2 mutants, which suggested that suppression of octopamine signaling by dopamine immediately results in suppression of the high locomotor activity state. In males, it required a few hours for dopamine to work on cat-2 mutants and the effect persisted for hours. Because dopamine had effects on adult cat-2 mutants, dopamine works at least in part independently of male development. The reason for the delay and persistence is unknown, but dopamine may be regulating states through slow signaling, such as induction of gene expression. The CREB homolog CRH-1 may play a role in such signaling, as crh-1 loss of function partially suppressed the effect of cat-2 on behavioral states in males.

The genes working in the dopaminergic regulation, including the receptors, were also different in males and hermaphrodites. For suppression of the dwelling state in males, dopamine acts in the same pathway as the polycystic kidney disease-related genes, lov-1 and pkd-2. lov-1 and pkd-2 work in the same pathway for the regulation of male mating behavior and are expressed exclusively in male-specific sensory neurons (Barr and Sternberg, 1999; Barr et al., 2001). Therefore, the dopaminergic pathway for behavioral state regulation in males may involve the male-specific sensory neurons. The fact that these neurons do not exist in hermaphrodites and are not fully developed in L4 males (Sulston et al., 1980) is consistent with the results showing that the male-specific regulation does not work in hermaphrodites and L4 males. Involvement of sex-specific neurons may be one of the mechanisms for the sexually dimorphic regulation of behavioral states.

The results shown in this study demonstrate that, in hermaphrodites, dopamine decreases locomotor activity through the suppression of octopamine signaling in the SIA neurons. Serotonin also regulates the behavioral states in hermaphrodites through octopamine signaling in the SIA neurons (Churgin et al., 2017). Furthermore, cat-2 and tph-1 mutants had similar percentage of dwelling, and cat-2 did not further decrease percentage of dwelling of tph-1. Therefore, it is likely that dopamine and serotonin signaling converge on suppression of octopamine signaling.

The SIA neurons are sex-shared neurons, existing in males and hermaphrodites (White et al., 1986). Through calcium imaging of the SIA neurons, we showed that the SIA neurons of hermaphrodites respond to octopamine by evoking calcium oscillation in a manner that requires the octopamine receptors. In contrast, the calcium response to octopamine was severely reduced in the SIA neurons of males. This result suggests that the SIA neurons of males have reduced responsiveness to octopamine compared with those of hermaphrodites. Therefore, in males, dopaminergic regulation of octopamine signaling would have less of an effect on the behavioral states. Such a sex difference in the responsiveness of the sex-shared neurons is likely another mechanism for the sexually dimorphic regulation of behavioral states. As masculinization of the SIA neurons by itself did not alter octopamine response or behavioral states of hermaphrodites, it is unlikely that the sex differences in bioamine signaling were determined by the sex of the SIA neurons, and other neurons may be involved. Further studies are required to elucidate the neural circuit that gives rise to the sexually dimorphic signaling.

Males spending more time in the high locomotor activity state may be beneficial for finding mates. Indeed, males explored a larger area of the bacteria lawn than hermaphrodites, and dopamine was responsible for a part of this sex difference. For hermaphrodites, it may be more beneficial to be less active as it allows them to stay with food and potentially conserve energy. The observation that sexually immature L4 males spent most of the time in the inactive dwelling state, similarly to hermaphrodites, is consistent with this idea. Male-female species also had sex differences in locomotor activity. Although females require males for reproduction, this may be explained by the fact that females have higher reproductive costs than males since they bear eggs. Recent simulation studies offer an alternative explanation for the sex difference in locomotor activity. Mizumoto et al. (2017) showed that sex differences in locomotion allow for a higher rate of encounter for 2 individuals of different sexes. In particular, if one sex is sending an attracting signal and is moving slower than signal receivers, it improves the chance of mating encounters (Mizumoto and Dobata, 2018). As C. elegans males are attracted to pheromones from hermaphrodites (Simon and Sternberg, 2002), the lower locomotor activity of hermaphrodites may help males find them. In addition to how they move within bacterial lawn, whether to leave the lawn impacts the chance of finding mates. Males leave a lawn at a much higher rate than hermaphrodites in the absence of mates. This difference is believed to be beneficial to males for finding a mate and helps hermaphrodites to stay with food. We found that dopamine also contributes to generating the sex differences in food-leaving by increasing food-leaving in males and decreasing it in hermaphrodites. These results suggest that dopamine is important for behavioral differentiation and promotes adaptive behaviors for each sex.

For tuning sex-shared behaviors to suit reproductive strategy of each sex, neuromodulator signaling that controls these behaviors needs to be altered in a sexually dimorphic manner. Our results show that a neurotransmitter, dopamine, controls the same behavior in the opposite way using different molecular mechanisms in different sexes, illustrating that animals can vary their behavior in a way that is adaptive to their sex without changing the associated neurotransmitter.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI 16K07063 to S.S. pDEST-GCaMP6 was provided by Comprehensive Brain Science Network (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan). Some C. elegans mutants were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs P40 OD010440. Some deletion mutants were provided by the National BioResource Project (Tokyo Women's Medical University). We thank Dr. Yuichi Iino and laboratory members for valuable comments and support with imaging experiments; and Dr. Douglas Portman for rab-3::fem-3.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Auer TO, Benton R (2016) Sexual circuitry in Drosophila.Curr Opin Neurobiol 38:18–26. 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr MM, Sternberg PW (1999) A polycystic kidney-disease gene homologue required for male mating behaviour in C. elegans.Nature 401:386–389. 10.1038/43913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr MM, DeModena J, Braun D, Nguyen CQ, Hall DH, Sternberg PW (2001) The Caenorhabditis elegans autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease gene homologs lov-1 and pkd-2 act in the same pathway. Curr Biol 11:1341–1346. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00423-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr MM, García LR, Portman DS (2018) Sexual dimorphism and sex differences in Caenorhabditis elegans neuronal development and behavior. Genetics 208:909–935. 10.1534/genetics.117.300294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios A, Nurrish S, Emmons SW (2008) Sensory regulation of C. elegans male mate-searching behavior. Curr Biol 18:1865–1871. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios A, Ghosh R, Fang C, Emmons SW, Barr MM (2012) PDF-1 neuropeptide signaling modulates a neural circuit for mate-searching behavior in C. elegans.Nat Neurosci 15:1675–1682. 10.1038/nn.3253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EA, Hobert O (2018) Past experience shapes sexually dimorphic neuronal wiring through monoaminergic signalling. Nature 561:117–121. 10.1038/s41586-018-0452-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Arous J, Laffont S, Chatenay D (2009) Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans.PLoS One 4:e7584. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans.Genetics 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase DL, Koelle MR (2007) Biogenic amine neurotransmitters in C. elegans.WormBook 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis N, Zimmer M, Bargmann CI (2007) Microfluidics for in vivo imaging of neuronal and behavioral activity in Caenorhabditis elegans.Nat Methods 4:727–731. 10.1038/nmeth1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churgin MA, McCloskey RJ, Peters E, Fang-Yen C (2017) Antagonistic serotonergic and octopaminergic neural circuits mediate food-dependent locomotory behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans.J Neurosci 37:7811–7823. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2636-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa PA, Gruninger T, García LR (2015) DOP-2 D2-like receptor regulates UNC-7 innexins to attenuate recurrent sensory motor neurons during C. elegans copulation. J Neurosci 35:9990–10004. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0940-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P, LeBoeuf B, García LR (2012) C. elegans dopaminergic D2-like receptors delimit recurrent cholinergic-mediated motor programs during a goal-oriented behavior. PLOS Genetics 8:e1003015. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell SW, Pokala N, Macosko EZ, Albrecht DR, Larsch J, Bargmann CI (2013) Serotonin and the neuropeptide PDF initiate and extend opposing behavioral states in C. elegans.Cell 154:1023–1035. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M, Sengupta P, McIntire SL (2002) Regulation of body size and behavioral state of C. elegans by sensory perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron 36:1091–1102. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01093-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison JL, Macosko EZ, Bernstein S, Pokala N, Albrecht DR, Bargmann CI (2012) Oxytocin/vasopressin-related peptides have an ancient role in reproductive behavior. Science 338:540–543. 10.1126/science.1226201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti S, Ferveur JF, Martin JR (2000) Genetic identification of neurons controlling a sexually dimorphic behaviour. Curr Biol 10:667–670. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. (2002) PCR fusion-based approach to create reporter gene constructs for expression analysis in transgenic C. elegans.Biotechniques 32:728–730. 10.2144/02324bm01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R, Gentleman R (1996) R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J Comput Graphic Statist 5:299–314. 10.1080/10618600.1996.10474713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell TA, Wang Y, Bloniarz AE, Brittin CA, Xu M, Thomson JN, Albertson DG, Hall DH, Emmons SW (2012) The connectome of a decision-making neural network. Science 337:437–444. 10.1126/science.1221762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Fujita K, Katsura I (2010) Enhancement of odor avoidance regulated by dopamine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans.J Neurosci 30:16365–16375. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6023-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM, French RP, Park EC, Johnson JJ (1990) The Caenorhabditis elegans rol-6 gene, which interacts with the sqt-1 collagen gene to determine organismal morphology, encodes a collagen. Mol Cell Biol 10:2081–2089. 10.1128/MCB.10.5.2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBoeuf B, Correa P, Jee C, García LR (2014) Caenorhabditis elegans male sensory-motor neurons and dopaminergic support cells couple ejaculation and post-ejaculatory behaviors. Elife 3:e02938. 10.7554/eLife.02938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Portman DS (2007) Neural sex modifies the function of a C. elegans sensory circuit. Curr Biol 17:1858–1863. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lints R, Emmons SW (1999) Patterning of dopaminergic neurotransmitter identity among Caenorhabditis elegans ray sensory neurons by a TGFbeta family signaling pathway and a hox gene. Development 126:5819–5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton J, Kleemann G, Ghosh R, Lints R, Emmons SW (2004) Mate searching in Caenorhabditis elegans: a genetic model for sex drive in a simple invertebrate. J Neurosci 24:7427–7434. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1746-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly S, Pack AI, Naidoo N (2018) The neurobiological basis of sleep: insights from Drosophila.Neurosci Biobehav Rev 87:67–86. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariol MC, Walter L, Bellemin S, Gieseler K (2013) A rapid protocol for integrating extrachromosomal arrays with high transmission rate into the C. elegans genome. J Vis Exp 82:e50773. 10.3791/50773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM. (2016) Multifaceted origins of sex differences in the brain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371:20150106. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills H, Wragg R, Hapiak V, Castelletto M, Zahratka J, Harris G, Summers P, Korchnak A, Law W, Bamber B, Komuniecki R (2012) Monoamines and neuropeptides interact to inhibit aversive behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans.EMBO J 31:667–678. 10.1038/emboj.2011.422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto N, Dobata S (2018) The optimal movement patterns for mating encounters with sexually asymmetric detection ranges. Sci Rep 8:3356. 10.1038/s41598-018-21437-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto N, Abe MS, Dobata S (2017) Optimizing mating encounters by sexually dimorphic movements. J R Soc Interface 14:20170086. 10.1098/rsif.2017.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mong JA, Cusmano DM (2016) Sex differences in sleep: impact of biological sex and sex steroids. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371:20150110. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowrey WR, Portman DS (2012) Sex differences in behavioral decision-making and the modulation of shared neural circuits. Biol Sex Differ 3:8. 10.1186/2042-6410-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowrey WR, Bennett JR, Portman DS (2014) Distributed effects of biological sex define sex-typical motor behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans.J Neurosci 34:1579–1591. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4352-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Koga M, Ohshima Y (2001) DAF-7/TGF-β expression required for the normal larval development in C. elegans is controlled by a presumed guanylyl cyclase DAF-11. Mech Dev 109:27–35. 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00507-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima T, Oami E, Kutsuna N, Ishiura S, Suo S (2016) Dopamine regulates body size in Caenorhabditis elegans.Dev Biol 412:128–138. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura M, Sasaki T, Sadakari J, Gengyo-Ando K, Kagawa-Nagamura Y, Kobayashi C, Ikegaya Y, Nakai J (2012) Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLoS One 7:e51286. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oranth A, Schultheis C, Tolstenkov O, Erbguth K, Nagpal J, Hain D, Brauner M, Wabnig S, Steuer Costa W, McWhirter RD, Zels S, Palumbos S, Miller Iii DM, Beets I, Gottschalk A (2018) Food sensation modulates locomotion by dopamine and neuropeptide signaling in a distributed neuronal network. Neuron 100:1414–1428. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priess JR, Schnabel H, Schnabel R (1987) The glp-1 locus and cellular interactions in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 51:601–611. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90129-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol N, Torregrossa P, Ewbank JJ, Brunet JF (2000) The homeodomain protein CePHOX2/CEH-17 controls antero-posterior axonal growth in C. elegans.Development 127:3361–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringstad N, Abe N, Horvitz HR (2009) Ligand-gated chloride channels are receptors for biogenic amines in C. elegans.Science 325:96–100. 10.1126/science.1169243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder T. (1999) Octopamine in invertebrates. Prog Neurobiol 59:533–561. 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrucca L, Fop M, Murphy TB, Raftery AE (2016) mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. R J 8:289–317. 10.32614/RJ-2016-021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]