Abstract

Introduction:

Dual-smoker couples are a highly prevalent group who report low motivation to quit smoking.

Aims:

This study tested the effect of a messaging intervention (couples- vs. individual-focused smoking outcomes) on motivation to quit among dual-smoker couples and examined the moderating effect of perceived support.

Methods:

A total of 202 individuals in 101 dual-smoker couples were randomized by dyad using a 2 (frame: gain/loss) by 2 (outcome focus: individual/couple) factorial design. Participants reviewed scenarios of either positive or negative outcomes of quitting versus not quitting as they applied to either the individual or the couple. Participants then reported their own motivation to quit and motivation for their partner to quit. The main outcome was motivation to quit smoking.

Results:

No main effects of framing or message focus emerged. Significant interactions between message focus and negative support predicted motivation for self and partner to quit. Individuals who reported lower negative support reported greater motivation for self to quit and less motivation for partner to quit after reviewing couple- (vs. individual-) focused messages.

Conclusions:

Individuals in dual-smoker couples typically report low motivation to quit smoking. Couple-focused messages may increase motivation to quit among individuals who are not receiving negative support from their partners.

Nearly two-thirds of smokers in romantic relationships are partnered with another smoker (vanDellen, Boyd, Ranby, MacKillop, & Lipkus, 2016). Individuals partnered with another smoker are more likely to relapse and less likely to become abstinent than individuals not partnered with another smoker (Ferguson, Bauld, Chesterman, & Judge, 2005; Garvey, Bliss, Hitchcock, Heinold, & Rosner, 1992). Smoking behaviour in dual-smoker couples is highly concordant; they often smoke together, share cigarettes, and buy cigarettes for their partner (Tooley & Borrelli, 2017). When one member of a dual-smoker couple quits, the other is more likely to subsequently become abstinent (Cobb et al, 2014; Homish & Leonard, 2005; Jackson, Steptoe, & Wardle, 2015). When dual-smoker couples choose to quit together, they can experience short-term success at attaining abstinence (Lüscher & Scholz, 2017). However, individuals in dual-smoker couples are not likely to quit together (Ranby, Lewis, Toll, Rohrbaugh, & Lipkus, 2013). Although 40% of individuals in dual-smoker couples claim to have quit smoking with their partner (Tooley & Borrelli, 2017), agreement about whether a quit attempt was joint is surprisingly low (Ranby et al, 2013). Moreover, individuals in dual-smoker couples often attribute relapse to their partners’ lapses or continued smoking (Tooley & Borrelli, 2017).

One approach to increasing motivation to quit among both partners is to draw on the dyadic nature of their smoking behaviour. That is, for dual-smoker couples, framing quitting as a dyadic rather than individual concern may increase motivation to quit (Doherty & Whitehead, 1986; Lewis et al., 2006; Shoham, Rohrbaugh, Trost, & Muramoto, 2006). Although bringing both partners into smoking treatment programs may increase abstinence rates (Nyborg & Nevid, 1986) and partners who quit together can be successful (e.g., Lüscher, Stadler, & Scholz, 2017), few interventions have considered explicitly how to motivate dual-smoker couples to quit at the same time (Lipkus, Ranby, Lewis, & Toll, 2013). Typically, messages highlight individual benefits of quitting (i.e., gain-framing) versus individual problems from not quitting (i.e., loss-framing; Toll et al., 2014). For dual-smoker couples, messages can also highlight how outcomes are relevant to the couple (Lipkus et al., 2013). When smoking is highly interdependent, as it is in dual-smoker couples, messages targeting the couple may increase motivation to quit more than messages targeting the individual.

Whether messages targeting the couple increase the motivation to quit may depend on the relationship context (Fitzsimons, Finkel, & vanDellen, 2015). Couple-rather than individual-focused messages might be more effective when members are committed to each other, are happy in the relationship (Knoll, Burkert, Scholz, Roigas, & Gralla, 2011; Lewis et al., 2006; Van Lange et al., 1997), and have a history of providing positive support rather than a history of conflict and negative support (Lepore, Allen, & Evans, 1993). Support is generally defined as an orientation towards providing resources for one’s partner (Cohen, Gottlieb, & Underwood, 2000), but has similar qualities as social control, which is generally defined as an attempt to influence one’s partner (Lewis & Rook, 1999). Measure of support and control are often conflated because they assess behaviours rather than intentions. In the present work, we use the term partner support (rather than social control) to be consistent with original conceptions of partner behaviours in the realm of smoking (Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990).

Not all forms of support produce health behaviour change. Positive support promotes health outcomes, whereas negative support is associated with poorer health outcomes (Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990). The primary distinction between positive and negative social support has involved an emphasis on their associations with health and relationship outcomes. Frequent positive partner support and control are associated with higher quit rates, whereas frequent negative support and negative control are associated with lower quit rates (Carlson, Goodey, Bennett, Taenzer, Koopmans, 2002; Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990; Lüscher & Scholz, 2017; Murray, Johnston, Dolce, Lee, & O’Hara, 1995; Roski, Schmid, & Lando, 1996). As these findings suggest, an important distinction exists between quantity and quality of partner support. Generally, positive support behaviours reflect confidence and encouragement. In contrast, negative support behaviours reflect expressions of doubt and nagging. Negative support behaviours often take the form of negative social control and lead to reactance in the support recipient (Craddock, vanDellen, Novak, & Ranby, 2015; Tucker, Orlando, Elliot, & Klein, 2006). Thus, we expect that positive relationship context (i.e., high positive and/or low negative support) may increase the effectiveness of dyadic messages. That is, individuals who perceive having better quality support for quitting from their partner will be more motivated to quit when messages focus on the dyad (vs. the individual).

The Present Study

This study was part of a larger project examining the combination of traditional message framing (i.e., gain/loss framing) and message focus (i.e., couple, individual) on motivation to quit in dual-smoker couples. Gain/loss framing alone did not influence motivation to quit or cessation by itself or in an interaction with focus; these findings are not discussed in this report. Instead, we address two questions related to the message focus manipulation. First, we examined the effects of couple- versus individual- focused messages on motivation to quit smoking. Because smoking is highly interdependent in dual-smoker couples, we expected couple-focused messages to increase motivation to quit among dual-smoker couples. Second, we expected relationship context (as assessed by positive and negative social support) to moderate the effect of the message focus, specifically expecting couple-focused messages to be more likely to promote motivations to quit when the relationship context was positive (i.e., high positive support, low negative support).

Traditionally, messaging studies evaluate effectiveness by change in a single participant’s motivation to quit. In dual-smoker couples, both individuals can quit smoking. Each person also may want their partners to quit to varying degrees (i.e., partner-directed motivation; Finkel, Fitzsimons, & vanDellen, 2016; Ranby et al., 2013). Evaluating messaging interventions effects for this population requires considering both how strongly people desire to quit themselves (i.e., self-directed motivation to quit) as well as how strongly people desire their partner to quit (i.e., partner-directed motivation to quit). Consequently, we examined how message focus and relationship context influence one’s own and desire that partner quit.

Methods

Participants

Couples in central North Carolina were recruited using newspaper and web-based advertisements (e.g., Craigslist). Each couple member had to be at least 18, be able to read and write in English, and currently smoke (at least 5 cigarettes/day + 100 lifetime cigarettes smoked (WHO, 1998). Couples had to be either married or cohabiting for at least 6 months. Of 479 individuals who completed a brief initial screener, 424 were found eligible. Of these, 245 enrolled in the study and completed baseline measurements. Of these, 102 couples attended an in-person laboratory session. All but one couple was heterosexual. One couple was deemed ineligible by the study PI due to stealing materials from the research office, leaving a total sample of 101 couples (total N = 202). The final sample afforded 80% power to detect interactions between focus (couple vs. individual) and relationship context of small-to-medium effect sizes (i.e., Cohen’s f > 0.2) on individual outcomes.

Procedures

Upon responding to advertisements, individuals were screened by a trained research assistant for eligibility. Permission was obtained to contact the partner of eligible individuals to assess partner eligibility. If both partners were eligible, verbal consent was collected and each individual took part in a separate baseline phone interview. Additional measures not discussed in this report were collected during the baseline phone interview. Couples then came to an in-person session, typically within 2 weeks of baseline. During this session, participants provided written consent. They completed a short battery of individual difference and relationship measures, in which social support was assessed. Based on the parent project’s primary aims, couples were randomized using a 2 (frame: gain/loss) by 2 (outcome focus: individual/couple) factorial design with the aim of including 50 individuals (25 couples) per condition. Participants were blind to condition and experimenters did not interact with participants between the administration of the condition materials (delivered on paper), and the surveys assessing the primary outcomes. The trial was not registered but local IRB approval was obtained for all study procedures.

Each partner separately reviewed four scenarios highlighting either positive outcomes of quitting or negative outcomes of not quitting wherein outcomes focused on either the individual or the couple. The full text of all scenarios is available in the supplementary material. Immediately after reviewing the scenarios, participants privately evaluated the scenarios and their motivations for self and partner to quit. Participants received $40 for study participation.

Measures

A summary of when each measure was assessed is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement of variables

| Time Point | Baseline | Lab session (Pre-manipulation) | Lab session (Post-manipulation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | |||

| Demographics (race, sex, education, smoking history) | X | ||

| Desire for self to quit | X | X | |

| Desire for partner to quit | X | X | |

| Partner support | X |

Demographic variables.

During the baseline session, individuals reported their years of smoking, nicotine dependence, age, sex, and race. Participants also reported their level of education (1= less than high school, 2 = some high school, 3 = high school graduate, 4 = technical or trade school, 5 = some college, 6 = college graduate, 7 = postgraduate).

Independent Variables

Couple versus individual focus.

Couples were randomly assigned to focus condition (individual vs. couple). A manipulation check asked participants to indicate whether the scenarios stressed the effects of smoking on a 0 (individuals who smoke) to 10 (couples who smoke) scale. The manipulation was effective with couple-focus scenarios (M = 8.34, SD = 2.52), viewed as more about couples than individual-focus scenarios (M = 2.59, SD = 3.18), t(98) = 14.08, p < 0.0001. Additionally, we assessed participants’ awareness that the messages they read changed how they felt about smoking on a scale from 1 (decreases my desire to quit) to 10 (increases my desire to quit).

Social support.

Prior to reviewing the messages, we assessed frequency of social support using items from the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ, Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990); 10 items assessed negative social support (e.g., refuse to clean up cigarette butts, express doubts about ability to quit smoking; α = 0.87) and 5 items assessed positive social support (e.g., express confidence in ability to quit, help calm partner when feeling stressed or irritable; α = 0.79). Participants responded to each item on a scale from 1 (never) to 7 (very often).

Dependent Variables

Motivation to quit smoking.

After reviewing the messages, participants reported their motivation to quit smoking using a single item (i.e., How strong is your desire to stop smoking at this time?), and their motivation for the partner to quit smoking using a single item (i.e., How strong is your desire that your partner quit smoking at this time?) from 1 (Not at all strong) to 7 (Extremely strong). Single items were used to reduce the participation demand on participants.

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using Proc Mixed in SAS version 9. Using multi-level modeling, individuals were nested into dyads (i.e., a two-level model; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). As a result, although all participants contributed individual data to analyses, reported degrees of freedom are based on number of dyads. All analyses were considered from the actor perspective only (i.e., the focus of this manuscript is on actor effects). That is, each individual reported their own perceived level of support from the partner and their own motivation to quit smoking.

Analyses were conducted treating Focus (Couple, Individual) as a categorical between-subjects variable and relationship context was treated as a continuous between-subjects variable and standardized prior to analysis Cohen, Cohen, Aiken, & West, 2003). Due to theoretical differences in the functions of positive and negative support, separate models were conducted treating each as a moderator representing relationship context. Relatively high and low levels of each independent variable were operationalized as one standard deviation above and below the mean (Cohen et al, 2003), allowing all data to be used in analyses and estimations of predicted means. No transformations were conducted on the dependent variables. Two-tailed tests with α = 0.05 were used to test all hypotheses.

As noted previously, gain/loss framing did not influence the outcomes reported here. Although observed results remain significant when controlling for gain/loss condition, results are reported here using the more parsimonious model (i.e., not controlling for gain/loss condition) but the online supplemental materials report analyses controlling for message framing. Because own and partner desire to quit were strongly related (r = 0.62, p < 0.0001), we conducted each analysis both independently and while controlling for the other. Effects observed from covariate analyses represent unique desire for a given target (self or partner) to quit. That is, higher scores on desire for self to quit (controlling for desire for partner to quit) represent desire for self to quit above and beyond any desire for partner to quit.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

Participants did not statistically differ across condition with regard to demographics, smoking history, or perceived positive and negative support (see Table 2). However, potentially non-trivial differences in groups emerged for education and race. Controlling for these variables did not change the observed effects and so the parsimonious models that do not include these covariates are reported.

Table 2.

Demographic and smoking information across condition

| Variables | Total sample (N = 202) | Couple-focus (N = 100) | Individual-focus (N = 102) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education (M, SD) | 3.78 (1.44) | 3.60 (1.45) | 3.95 (1.40) | 0.08 |

| Percent female | 49.5% | 50% | 48% | 0.89 |

| Ethnicity | 0.67 | |||

| Not Hispanic | 96.04% | 95.55% | 98.45% | |

| Hispanic | 3.47% | 3.45% | 3.55% | |

| Race | 0.10 | |||

| Caucasian | 21.78% | 16.00% | 27.45% | |

| African American | 72.28% | 79.00% | 65.86% | |

| Asian American Indian, Other | 5.94% | 5.00% | 6.86% | |

| Smoking and Relationship Context Measures | (M, SD) | (M, SD) | (M, SD) | p |

| Years smoking | 19.59 (10.85) | 19.91 (10.46) | 19.28 (11.22) | 0.68 |

| Fagerström score | 5.60 (2.00) | 5.74 (2.00) | 5.47 (2.00) | 0.34 |

| Negative support | 2.64 (1.40) | 2.75 (1.48) | 2.53 (1.31) | 0.26 |

| Positive support | 3.38 (1.51) | 3.45 (1.56) | 3.31 (1.46) | 0.51 |

| Baseline desire to quit | 4.51 (1.96) | 4.56 (1.94) | 4.47 (1.98) | 0.73 |

| Baseline desire for partner to quit | 5.08 (1.94) | 5.03 (1.85) | 5.12 (2.02) | 0.74 |

Motivation to Quit

Self-directed motivation.

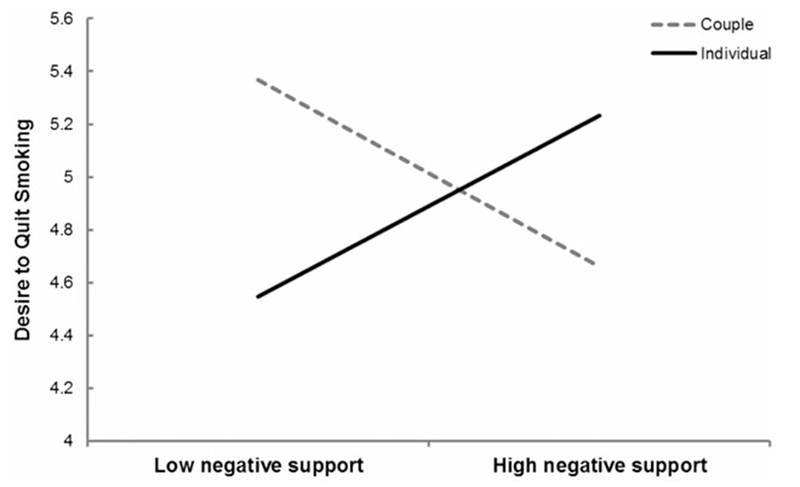

We found no support for the hypothesis that couple-focused messages (M = 5.02, SD = 1.80) increased own desire to quit relative to individual-focused messages (M = 4.94, SD = 1.79), F(1, 97) = 0.41, p = 0.52. However, the message focus manipulation had different effects on desire to quit depending on perceived negative support, F(1, 97) = 12.50, p < 0.001. This interaction remained significant even after controlling for baseline desire to quit F(1, 95) = 3.48, p < 0.001, suggesting observed effects were a function of change in motivation after reviewing the intervention. As shown in Figure 1, when levels of negative social support were relatively low, participants were more motivated to quit when messages were couple- rather than individual-focused, t(97) = 2.97, p < 0.01. Conversely, when levels of negative social support were relatively high, participants were more motivated to quit when messages were individual- rather than couple-focused, t(97) = 2.05, p = 0.04. The interaction and pattern of slopes remain significant when not controlling for partner-directed motivation, F(1, 97) = 2.53, p = 0.001. Thus, both unique variance in desire for self to quit (i.e., removing variance shared with desire for partner to quit) and total variance in desire for self to quit were similarly affected by the combination of focus condition and perceived negative support.

Figure 1.

The interaction between perceived negative support and focus predicts unique variance in desire to quit smoking (i.e., controlling for desire for partner to quit smoking).

Partner-directed motivation.

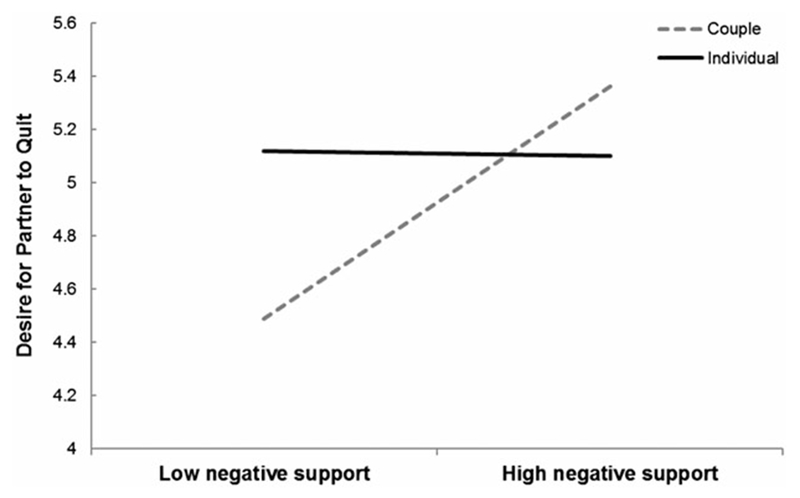

We found no effect of couple-focused messages on desire for one’s partner to quit smoking, (M = 5.08, SD = 1.91) relative to individual-focused messages (M = 5.00, SD = 2.05), F(1, 97) = 0.20, p = 0.66. Negative support moderated the effect of message focus on desire for partner to quit, F(1, 97) = 5.82, p = 0.02. This interaction remained significant even after controlling for baseline desire for partner to quit, F(1, 96) = 4.84, p = 0.03. As Figure 2 shows, individuals who reported receiving relatively low negative social support were more likely to want their partner to quit smoking in the individual- rather than in the couple-focused condition, t(97) = 2.04, p = 0.04. There was no effect of condition for participants who reported relatively high negative support, t(97) = 1.41, p = 0.16. The interaction and pattern of slopes do not remain significant without controlling for self-directed motivation, F(1, 97) = −0.30, p = 0.762. Thus, the combination of focus condition and negative support predicts unique variance in desire for partner to quit (i.e., when not controlling for desire for self to quit) but not the total variance in desire for partner to quit.

Figure 2.

The interaction between perceived negative support and focus predicts unique variance in desire for partner to quit smoking (i.e., controlling for own desire to quit smoking).

Additional Analyses

Positive and negative support were related (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), but positive support did not moderate the effect of message focus on motivations to quit, p’s > 0.30. Additionally, we observed no effects of message focus, negative or positive support, nor interactions between constructs on perception that messages had changed desire to quit, p’s > 0.16. Additional results reporting analyses on the difference between desire for self and partner to quit are presented online in the supplementary material. We further explored whether gender might moderate any observed effects; gender did moderate the interaction between focus condition and negative support in predicting desire for self to quit (when controlling for baseline desire to quit as well as simultaneous desire for partner to quit), F(1, 91) = 4.25, p = 0.04). This interaction, which suggests the interaction between focus condition and negative support is larger for women than men, is described in greater detail in the supplementary material.

Discussion

Individuals in dual-smoker couples viewed messages promoting smoking cessation in either a couple- or individual-focused presentation. We did not find the expected main effect of couple- (vs. individual-) focused messages on motivation to quit smoking. Instead, message focus affected motivation to quit depending on level of perceived negative social support. Individuals reporting low levels of negative support were more motivated to quit after reviewing couples- versus individual-focused messages. In contrast, individuals reporting relatively high levels of negative support were more motivated to quit after reviewing individual- versus couple-focused messages. A different pattern emerged for motivation for partner to quit smoking. Here, low levels of negative support produced greater motivation for the partner to quit in the individual-focus condition. Note that this pattern emerged only when controlling for desire for self to quit.

Combined, the results suggest that the couple (vs. individual) messages may have reduced the degree to which participants were more motivated for their partner to quit than for themselves to quit (see the online materials for a statistical exploration of this explanation). An alternative possibility is that the couple-focused message increased communal orientation (e.g., Clark & Mills, 2012), but that this sense of communal orientation only translated into motivation to quit when the relationship context was low in conflict (i.e., negative support). If the individual-focus condition did not increase communal orientation, motivation to quit may have been shifted to the partner, and especially when the partner appears somewhat open to quitting (i.e., provides low levels of negative support regarding smoking).

Study strengths include a) randomization of messages and b) utilizing a high-risk but understudied group of smokers. Moreover, the study design included recruiting and delivering messages to both members of a couple, testing the potential effectiveness of the dyadic focus. Given that dual-smoker couples are a difficult population to recruit, it is useful to consider how this study could inform future research on smoking cessation in dual-smoker couples. For instance, the present study suggests that main effects of interventions may be moderated by relationship context (particularly negative support) and that these constructs should be carefully assessed in future studies with dual-smoker couples. Findings also suggest that self-oriented and partner-oriented motivation may not move in tandem. More research will need to be conducted to determine whether self-oriented motivation (e.g., desire to quit) or increased motivation above and beyond partner (e.g., desire for self to quit more than partner) is more predictive of initiating smoking cessation.

Study limitations include a relatively small sample size for investigating interaction effects. A replication will be needed to increase confidence with the present results. Additionally, we did not include a no-message control condition. Given that past research has found reliable messaging effects (Toll et al., 2007; Toll et al., 2014), we chose to focus our resources on differentiating the effects of couple- versus individual-focus within these messages. However, the possibility remains that these messages were all effective (or were entirely ineffective) compared to no message among our sample of dual-smoker couples. Another limitation was the evaluation of negative support. No measures of support have been developed and tested specifically for dual-smoker couples. In the current study, we used 15 items (out of 20) from the PIQ (Cohen & Lichtenstein, 1990). However, the PIQ was not developed using dual-smoker couples, and may function differently in this group. Finally, the present study investigated only short-term changes in motivation to quit; further research will be needed to determine whether couple-focused messages produce quit attempts and eventual abstinence among dual-smoker couples.

Further evaluation is needed regarding whether negative support, as assessed by the PIQ, reflects an orientation toward providing resources (i.e., reflects support) or an orientation toward influencing the partner (i.e., reflects control). The observed association between positive and negative support may occur because both scales capture attempts by the partner to change one’s behaviour, although their different pattern of moderating results suggests their independent variance captured meaningful distinctions in how partner influence affects motivation to quit. The correlation between positive and negative support suggests one key aspect of negative support behaviours is a willingness to provide resources. Further measurement development to reliably discriminate supportiveness from desire for partner to change is certainly needed.

More generally, how negative support is experienced by recipients needs further attention. Perhaps recipients attribute the partner’s negative support to negative attitudes, for instance, perceiving negative support providers as more critical or doubtful of the recipient’s ability to change a behaviour. This interpretation is consistent with research showing that negative interactions affect well-being and are mediated by appraisals of attempted influence (Newsom, Rook, Nishishiba, Sorkin, & Mahan, 2005). Additionally, negative support items tend to capture interactions that signal relationship hostility and conflict (e.g., refusing to clean up a partner’s cigarette butts), which suggests they may capture other aspects of relationship dysfunction. Furthermore, negative and positive support items may not capture the same degree of intensity (Ingersoll-Dayton, Morgan, & Antonucci, 1997). An important question to continue to explore is how to best capture these varied negative social interactions that reduce motivation to quit smoking, and particularly among dual-smoker couples, who are already less likely to provide high quality social support during smoking cessation (McBride et al., 1998; vanDellen et al., 2016).

Findings suggest promising directions for further exploration regarding smoking cessation in dual-smoker couples. First, study findings suggest that in dual-smoker couples, a population generally unlikely to quit smoking, carefully crafted messages that fit their relationship characteristics may increase their motivation to make a cessation attempt. Thus, interventionists focusing on couples may consider segmenting couples into those who are high and low in negative support. Researchers may also consider developing interventions for dual-smoker couples that target quality of social support—training individuals to provide positive rather than negative support, or express their desire to help their partner in positive rather than critical ways. Finally, because members of dual-smoker couples are unlikely to quit smoking at the same time (Ranby et al., 2013; Tooley & Borrelli, 2017), they face challenges to quitting when the partner does not also quit. Thus, interventions that simultaneously increase motivation for self to quit among both partners need to be developed.

Conclusions

The present study finds couple-focused messages (regardless of gain vs. loss framing) to be effective at increasing motivation to quit among dual-smoker couples so long as an individual is receiving low levels of negative support from the partner. In cases of high levels of negative support, individual-focused messages are more effective at increasing motivation to quit. Combined results suggest (a) individuals may carry different motivations for themselves and their partner to quit and (b) effectively intervening with dual-smoker couples likely requires understanding their relationship context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

All authors were involved in conceptualizing this manuscript. M. vanDellen led the analyses and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. The contents of the manuscript have not been published elsewhere.

Financial Support

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health under Grants R21-CA165194 and P30-DA023026.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Toll received an investigator initiated grant from Pfizer for medicine only, and he testified as an expert witness in litigation filed by plaintiffs against the tobacco industry.

Ethical Standards

Ethical standards of the local institution were followed in the conduct of this research. All data was collected at Duke University, whose IRB approved the study.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jsc.2018.19.

References

- Carlson LE, Goodey E, Bennett MH, Taenzer P, & Koopmans J (2002). The addition of social support to a community-based large-group behavioral smoking cessation intervention: Improved cessation rates and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 547–559. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, & Mills JR (2012). A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships In Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, & Higgins ET (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology: Volume Two (pp. 232–250). California: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb LK, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Huxley RR, Woodward M, Koton S, Coresh J et al. (2014). The association of spousal smoking status with the ability to quit smoking: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179, 1182–1187. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Gottlieb B, & Underwood L (Eds.) (2000). Measuring and intervening in social support. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Lichtenstein E (1990). Partner behaviors that support quitting smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58, 304–309. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock E, vanDellen MR, Novak SA, & Ranby KW (2015). Influence in relationships: A meta-analysis on health-related social control. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37, 118–130. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2015.1011271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, & Whitehead DA (1986). The social dynamics of cigarette smoking: A family systems perspective. Family Processes, 25, 453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1968.00453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, & Judge K (2005). The English smoking treatment services: One year outcomes. Addiction, 100(Suppl. 2), 59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.13600443.2005.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, & Fitzsimons GM, & vanDellen MR (2016). Self-regulation as a transactive process: Reconceptualizing the unit of analysis for goal setting, pursuit, and outcomes In Vohs KD, & Baumeister RF (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons GM, Finkel EJ, & vanDellen MR (2015). Transactive goal dynamics. Psychological Review, 122, 648–673. doi: 10.1037/a0039654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, & Rosner B (1992). Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: A report from the Normative Aging Study. Addictive Behaviors, 17, 367–377. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, & Leonard KE (2005). Spousal influence on smoking behaviors in a US community of newly married couples. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 2557–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Morgan D, & Antonucci T (1997) The effects of positive and negative social exchanges on aging adults. Journal of Gerontology B-Psychological and Social Sciences, 52, S190–S199. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.4.s190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Steptoe A, & Wardle J (2015). The influence of partner’s behavior on health behavior change: The English longitudinal study of ageing. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175, 385–392. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). The Analysis of Dyadic Data. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll N, Burkert S, Scholz U, Roigas J, & Gralla O (2011). The dual-effects model of social control revisited: Relationship satisfaction as a moderator. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 25, 291–307. doi: 10.1080.10615806.2011.584188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Allen KA, & Evans GW (1993). Social support lowers cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 518–524. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Poliak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, & Emmons KM (2006). Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, & Rook K (1999). Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology, 18, 63–71. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkus IM, Ranby KW, Lewis MA, & Toll B (2013). Reactions to framing of cessation messages: Insights from dual-smoker couples. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 2022–2028. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher J, & Scholz U (2017). Does social support predict smoking abstinence in dual-smoker couples? Evidence from a dyadic approach. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30, 273–281. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1270448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher J, Stadler G, & Scholz U (2017). A daily diary study of joint quit attempts by dual-smoker couples: The role of received and provided social support. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13, 100–107. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC, Lando H, & Pirie PL (1998). Partner smoking status and pregnant smoker’s perceptions of support for and likelihood of smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 17, 63–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RP, Johnston JJ, Dolce JJ, Lee WW, & O’Hara P (1995). Social support for smoking cessation and abstinence: The lung health study. Addictive Behaviors, 20, 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, Sorkin DH, & Mahan TL (2005). Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: Examining specific domains and appraisals. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences B, 60, P304–P312. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg KF, & Nevid JS (1986). Couples who smoke: A comparison of couples training versus individual training for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy, 17, 620–625. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(86)80099-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranby KW, Lewis MA, Toll BA, Rohrbaugh MJ, & Lipkus IM (2013). Perceptions of smoking-related risk and worry among dual-smoker couples. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 734–738. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roski J, Schmid LA, & Lando HA (1996). Long-term associations of helpful and harmful spousal behaviors with smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors, 21, 173–185. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham V, Rohrbaugh MJ, Trost SE, & Muramoto M (2006). A family consultation intervention for health-compromised smokers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31, 395–40. doi: 10.1016/j.sat.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, O’Malley SS, Katulak NA, Wu R, Dubin JA, Latimer A et al. (2007). Comparing gain- and loss-framed messages for smoking cessation with sustained-release bupropion: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 534–544. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Rojewski AM, Duncan L, Latimer AE, Fucito LM, Boyer J et al. (2014). “Quitting smoking will benefit your health”: The evolution of clinician messaging to encourage tobacco cessation. Published as part of the AACR’s commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health. Clinical Cancel-Research, 20, 301–309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooley EM, & Borrelli B (2017). Characteristics of cigarette smoking in individual in smoking concordant and smoking discordant couples. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6, 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Orlando M, Elliott MN, & Klein DJ (2006). Affective and behavioral responses to health-related social control. Health Psychology, 25, 715–722. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanDellen MR, Boyd SM, Ranby KW, MacKillop J, & Lipkus I (2016). Willingness to support partner’s smoking cessation: A study of partners of smokers. Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 1840–1849. doi: 10.1177/1359105314567209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange PAM, Rusbult CE, Drigotas SM, Arriaga XE, Witcher BS, & Cox CL (1997). Willingness to sacrifice in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1373–1395. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1998). WHO guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.