Abstract

Intermittent hypoxemia events (IH) are common in extremely preterm infants and are associated with many poor outcomes including retinopathy or prematurity, wheezing, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cognitive or language delays and motor impairment. More recent data in animal and rodent models have suggested that specific patterns of IH may increase the risk for morbidity. The pathway by which these high risk patterns of IH initiate a pathological cascade is unknown but animal models suggest that oxidative stress may play a role. This review describes early postnatal patterns of IH in preterm infants, their relationship with morbidity, oxidative stress biomarkers relevant to the newborn infant and the relationship between IH and reactive oxygen species.

Keywords: Intermittent hypoxemia, hypoxia, oxidative stress, pulse oximetry

1. Introduction

Although advances in therapeutic interventions related to premature birth have improved survival, medical costs associated with both short and long term morbidity in these high risk neonates continue to rise. The increased risks of sequelae are multifactorial attributed to both immaturity and environmental causes. Many of the poor outcomes in preterm infants are induced by respiratory instability manifesting as apnea with associated bradycardia and intermittent hypoxemia (IH). In extremely preterm infants, IH are prolific (Di Fiore et al., 2010) and have been associated with multiple morbidities including retinopathy of prematurity (Di Fiore et al., 2010; Poets et al., 2015), wheezing (Di Fiore et al., 2018), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (Fairchild et al., 2018; McEvoy et al., 1993; Raffay et al., 2018), neurodevelopmental impairment(Poets et al., 2015), and mortality (Di Fiore et al., 2017). Current therapies attempting to stabilize respiration and oxygenation include both invasive and non-invasive respiratory support (ie continuous positive airway pressure, nasal cannula, or mechanical ventilation), supplemental oxygen, and caffeine. These therapeutic modalities themselves have been associated with morbidity. Therefore, it is important to be able to distinguish the damaging contributions of clinical interventions, particularly supplemental oxygen, from IH. There are multiple pathways in which IH and corresponding therapies can cause poor outcomes including initiation of a pathological inflammatory or oxidative stress induced cascade.

Under normal physiologic circumstances, only a small percentage of oxygen undergoes incomplete reduction to form reactive oxygen species (ROS), and most ROS are neutralized by enzymatic antioxidants and non-enzymatic scavengers. Nonetheless, under stressful metabolic situations such as infections, hypoxia-reoxygenation, hyperoxia, radiation, and/or parenteral nutrition containing oxidizable components, a burst of free radicals that overcomes the antioxidant defense system may be generated. This can lead to oxidative/nitrosative stress which will not only cause direct functional and structural damage to tissue but also trigger the activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-kB and pro-apoptotic pathways that contribute to enhancement of the initial damage(Millan et al., 2018).

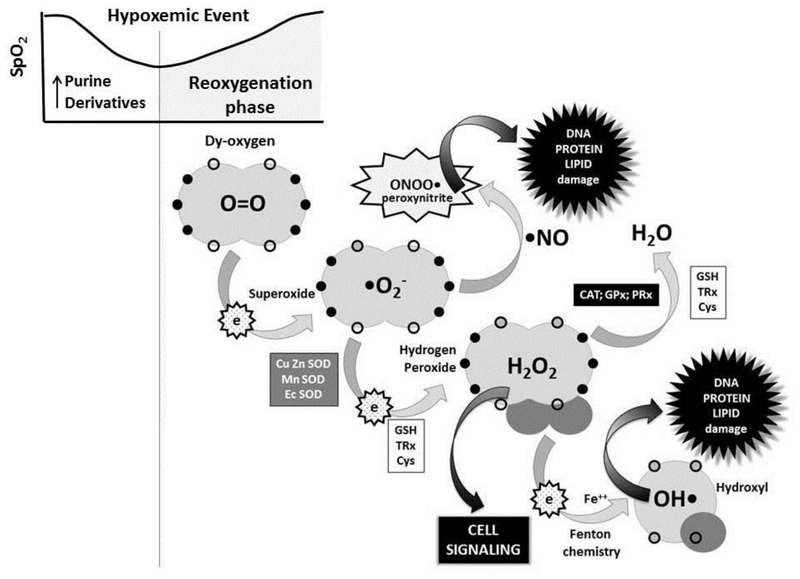

Among the pathological circumstances that lead to the generation of oxygen free radicals is intermittent hypoxia. During hypoxia, there is an exhaustion of ATP especially in the highly oxygen-dependent tissues such as brain and myocardium that leads to the formation and accumulation of purine derivatives such as hypoxanthine. Upon reoxygenation, there is an activation of oxidases, especially the NADPH oxidase family (Block and Gorin, 2012) and xanthine oxidases (Saugstad et al., 2018), that metabolize purine derivatives and generate a burst of superoxide anion causing intense oxidative stress and tissue damage. [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

-During reoxygenation following a hypoxemic event, stepwise reduction of oxygen generates superoxide anion (monovalent reduction) which either dismutates by the action of Superoxide Dismutases (Cu Zn SOD, Mn SOD, Ec SOD) to Hydrogen Peroxide, or reacts with nitric oxide to form peroxynitrite leading to DNA, protein and/or lipid damage. Hydrogen peroxide can be reduced to water by the action of Catalase (CAT), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) or Peroxiredoxin (PRx). Hydrogen peroxide acts as a potent cell signaling molecule regulating essential pathways related to cell physiology. However, in the presence of transition metals (ie. iron, copper, manganese, zinc) Fenton chemistry ensues converting hydrogen peroxide to hydroxyl radical, a highly reactive free radical capable of causing oxidative damage to cell components.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) is the most potent cytosolic non-enzymatic antioxidant. The combination of two disulfide bonds (2GSH) in a disulfur bond leads to the formation of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and the liberation of 2 electrons which are employed by GPx and CAT to neutralize hydrogen peroxide. Similar changes are experiences by reduced Thioredoxin and Cysteine when transformed into oxidized Thioredoxin (TRx) and Cystine (Cys). The switch from sulfur to disulfide bonds is an essential antioxidant mechanism. Moreover, the SH/S=S ratio in these three couples is essential for the maintenance of the redox status of the different cellular and extracellular compartments. An adequate redox status determines normal cell signaling such as cell division, growth, and differentiation, or in excess, activation of DNA, Protein and/or Lipid damage such as autophagy, apoptosis or necrosis. Note: open circles represent empty orbital loci without electrons; black circles represent orbital loci occupied by electrons.

This chapter focuses on the occurrence of IH events during early postnatal life in preterm infants and the relationship between IH and oxidative stress during this critical developmental window.

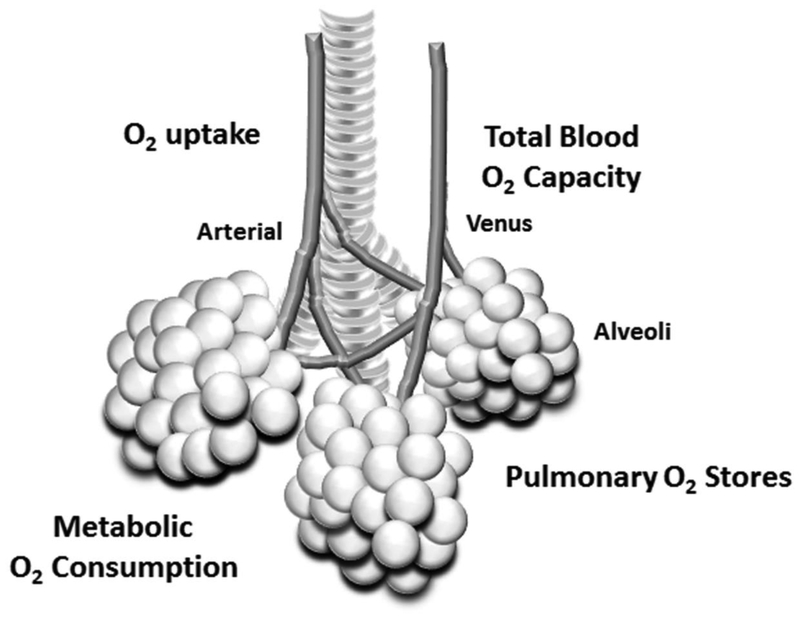

2. Intermittent Hypoxemia

Respiratory instability is prolific in extremely preterm infants manifesting as apnea with associated bradycardia and intermittent hypoxemia. In preterm infants, immature respiratory control plays a role in the initiation of apnea but the occurrence of accompanying IH may be enhanced by increased metabolic oxygen consumption and poor respiratory function (ie. decreased oxygen uptake by the alveoli, pulmonary oxygen stores, and total blood oxygen carrying capacity(Sands et al., 2010)[FIGURE 2]. As a result IH may present in response to very short respiratory pauses.

Figure 2.

-In preterm infants, the occurrence of IH in response to a respiratory pause may be enhanced by increased metabolic oxygen consumption and poor respiratory function (ie. decreased oxygen uptake by the alveoli, pulmonary oxygen stores, and total blood oxygen carrying capacity)

2.1. Methodology

Arterial blood gas sampling is the gold standard for measuring oxygen levels in the NICU setting but sporadic estimates of PaO2 are inadequate in identifying the rapid fluctuations in oxygen levels that often occur in extremely preterm infants. Transcutaneous and pulse oximetry monitoring provide continuous documentation of oxygen levels in the NICU setting. Although transcutaneous monitoring provides a more stable waveform, pulse oximetry has a rapid response time, and does not require calibration or heat at the probe site. As a result pulse oximetry has been incorporated into standard cardiorespiratory monitoring practice at the bedside.

Oxygen saturation values can vary among oximeter manufacturers due to the type of hemoglobin measured (functional vs fractional), motion detection algorithms and calibration curves. It should also be noted that pulse oximetry accuracy decreases at lower levels of SpO2 (Rosychuk et al., 2012) with data in lambs revealing a mean difference as high as 13–17% between SpO2 and SaO2 at SaO2 levels <70% (Dawson et al., 2014). Due to the plateau of the oxygen dissociation curve, pulse oximetry also has limited value in identifying periods of hyperoxemia with the use of supplemental oxygen and, although correlated with PaO2, oxygen saturation has a wide error range when compared on a point by point basis (Quine and Stenson, 2009).

Preterm infants exhibit wide fluctuations in oxygen saturation but there is no standard definition of an IH event. Common IH thresholds include <80, <85 or <90% and are often based on the oxygen saturation target that can vary among NICUs. It should also be noted that pulse oximeter settings, notably the averaging time, can play an important role in detection of IH. For example, a short averaging time (ie 2sec) will produce the most accurate oxygen saturation waveform (Vagedes et al., 2013) while a longer averaging time (ie 16sec) often used to reduce nuisance alarms can distort the oxygen saturation waveform by creating falsely prolonged IH when multiple short self-resolving IH occur in close proximity. This is concerning as longer IH are more likely to receive additional and possibly unnecessary supplemental oxygen.

While transcutaneous and/or pulse oximetry provide measures of blood oxygen levels, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring can provide continuous monitoring of regional tissue oxygenation in the brain and other organs. Used in conjunction with SpO2, NIRS has promise in identifying infants at risk for organ dysfunction but is limited by the lack of normative data and absolute threshold values for predicting poor outcomes.(Sood et al., 2015)

Lastly, accurate documentation of events in the EMR is problematic with nursing documentation being widely known to grossly underestimate the true number of cardiorespiratory events. In fact, data have shown that less than half of even clinically significant events requiring intervention are noted in the medical record (Brockmann et al., 2013). Future NICU platforms are moving towards downloading waveforms to central servers which should improve accuracy of event detection.

2.2. IH events and morbidity

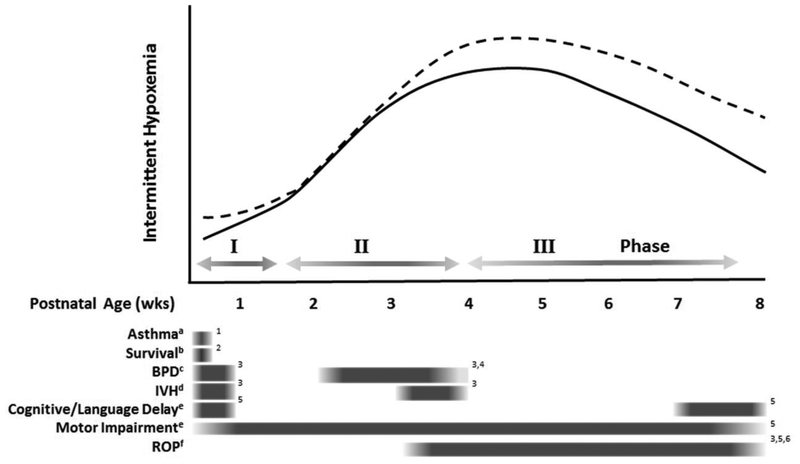

In extremely preterm infants the natural progression of IH begins with relatively few events during the first week of life followed by a rapid increase in the 2nd and 3rd wks of life (Di Fiore et al., 2010) [FIGURE 3]. This postnatal pattern decreases with increasing gestational age (Di Fiore et al., 2010; Fairchild et al., 2016). During the first month of life the duration of IH shorten but increase in severity (Di Fiore et al., 2012). In addition, the majority of IH take place in clusters < 20 min apart with approximately half of all events occurring <1min apart. There are many factors that may play a role in these transient IH patterns during early postnatal life including transition from fetal to adult hemoglobin, decreasing levels of serotonin (Schumacher et al., 1987) and myo-inositol(Hallman et al., 1992) and the switch of GABA from an excitatory to inhibitory state.(Ben-Ari et al., 2007)

Figure 3.

-The association between postnatal progression of intermittent hypoxemia events (IH) and poor outcomes in very low birthweight preterm infants. The average incidence of IH (solid line) during the first week of life is relatively low (Phase I), followed by a progressive increase during the second week of life (Phase II), peaking at approximately 4 weeks and decreasing thereafter (Phase III). A higher incidence of IH (dashed line) has been associated with multiple morbidities but current studies suggest that the timing of the increase in IH may be outcome dependent. For example, a higher incidence of IH during the first 3 days of life has been associated with an increased risk of asthma at 2yrs of age, while a higher frequency of IH after 3 to 5wks of age has been associated with retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). Transitional phases denoted by grey arrows. Significant associations between IH and individual morbidities are represented by grey boxes. Fading edges signify general postnatal windows as opposed to a fixed specific time.

a use of asthma medications at 2 year follow up

b 90-day survival

c BPD-bronchopulmonary dysplasia defined as supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks corrected age

d IVH-intraventricular hemorrhage during hospitalization

e at a corrected age of 18 to 21 months

f ROP-severe retinopathy of prematurity requiring intervention during ospitalization

References:

Therapeutic modalities used to reduce apnea and/or IH in the clinical setting include respiratory support (ie continuous positive distending pressure (CPAP), nasal cannula or mechanical ventilation), and supplemental oxygen. Nasal CPAP provides continuous distending pressure to the airways improving stabilization of lung volume, and reducing apnea. Additional positive pressure cycles can be superimposed on the background pressure (nasal intermittent positive pressure or N-IPPV) to provide further support with each breath and avoid intubation (Bancalari and Claure, 2013). Continued respiratory instability may require mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen. Interestingly, most preterm infants still exhibit IH while on mechanical respiratory support due to abdominal muscular contraction during exhalation leading to a decrease in lung volume. (Bancalari and Claure, 2018). Supplemental oxygen is often used with both invasive and non-invasive ventilation but may not always be successful in maintaining stable oxygenation, especially in the presence of anemia. Although studies have reported conflicting findings, red blood cell transfusions may lessen IH by enhancing the oxygen carrying capacity to the brain thereby improving respiratory control and/or increasing oxygen reserves resulting in greater stability during apnea (Abu Jawdeh et al., 2014).

There is strong evidence suggesting that IH may be associated with morbidity in both animal and human neonatal models. The largest body of literature focuses on retinopathy of prematurity. Multiple neonatal rodent studies have characterized a wide range of intermittent hypoxia exposures causing retinopathy (Coleman et al., 2008; Hartnett, 2010; Penn et al., 1995; Werdich et al., 2004) signifying that alterations in magnitude, duration and timing of hypoxia cycles determine the severity of the neovascular response. Initial studies in preterm infants with low resolution data found that increased variability of blood gas or intermittent transcutaneous monitoring (every 6 hrs) were predictive of severe ROP. (Cunningham et al., 1995; York et al., 2004). More recent studies have focused on further comprehensive analysis of continuous oxygen saturation waveforms to capture the highly dynamic rapid fluctuations in oxygenation. Using continuous pulse oximetry monitoring during the first few months of life in a single center cohort, severe ROP has been associated with more defined IH paradigms including a higher number of IH after 5wks of age (Di Fiore et al., 2010)[Figure 3], of longer duration, a higher nadir and a time interval between IH events of 1–20 min (Di Fiore et al., 2012). Larger studies in cohorts of 500–1000 VLBW infants have found an association between increased frequency and/or percent time with hypoxemia and severe ROP after 3 and/or 5wks of age (Fairchild et al., 2018; Poets et al., 2015) that were limited to IH >1min in duration (Poets et al., 2015).

Fluctuations in oxygenation may also play a critical role in early brain development. In neonatal rodents, repetitive hypoxia exposure evokes disruption in sleep architecture (Gozal et al., 2001a), and alterations in executive function manifesting as impaired working memory (Decker et al., 2003; Gozal et al., 2001b; Ratner et al., 2007), and hyperactive behavior (Decker et al., 2005). These examples of brain dysfunction were accompanied by a reduction in extracellular levels of dopamine(Decker et al., 2003; Decker et al., 2005), increased cerebral expression of caspase-3 (Ratner et al., 2007) and a marked increase in apoptosis in the CA1 hippocampal region and cortex (Gozal et al., 2001a). These results correspond with the disproportionately high occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in preterm infants and strong association with SDB and behavioral comorbidities in this vulnerable population(Emancipator et al., 2006). Additional studies in preterm infants have shown a relationship between apnea, as a marker of IH, during early hospitalization and neurodevelopmental impairment at multiple ages including early infancy (Hunt et al., 2004; Pillekamp et al., 2007), 3 years of age (Janvier et al., 2004) and early school age (Taylor et al., 1998). Lastly, a retrospective analysis of infants enrolled in the Canadian Oxygen Trial found a relationship between increased early postnatal time with hypoxemia and increased risk of motor impairment and cognitive or language delay at 18 months corrected age (Poets et al., 2015)[Figure 3].

Intermittent hypoxemia events during early postnatal life may be a risk factor for both short and long term respiratory morbidity. Because of their immature lungs and high incidence of IH during early postnatal life, premature newborns often require supplemental oxygen and positive pressure support. These interventions may themselves increase risk for future respiratory disorders thereby making it challenging to distinguish the relative contributions of IH from therapeutic interventions. Translational animal models indicate that neonatal IH alone is unlikely to cause parenchymal and mechanical BPD lung changes, (Dylag et al., 2017; Ratner et al., 2009) but IH in the setting of supplemental oxygen creates an equal or more severe BPD phenotype. (Dylag et al., 2017; Mankouski et al., 2017; Ratner et al., 2009). However, two recent studies have shown a relationship between the frequency and duration of IH and BPD in very low birthweight infants (Fairchild et al., 2018; Raffay et al., 2018) during the first month of life with the most consistent relationships occurring after 21 days of life [Figure 3]. Wheezing disorders and asthma like symptoms are among the most common childhood sequelae with one in three preterm infants exhibiting childhood wheezing(Jaakkola et al., 2006). In contrast to BPD, early exposure to IH events during the first 3 and 7 days of life have been associated with reported asthma medication use at 2 years of age (Di Fiore et al., 2018). These data suggest that there may be different developmental windows related to the progression of BPD versus asthma/wheezing. For example, the increase in IH events during the 1st week of life may induce airway remodeling while the progressively higher frequency of IH after the 2nd week of life may alter alveolar development. Further studies in these developmental windows are needed.

Animal models have shown that IH alone can evoke vascular, behavioral and neurochemical alterations leading to disorders such as ROP and NDI but IH may also act in conjunction with additional risk factors to induce a pathological cascade. For example, >15 IH per day during the 1st three days of life is associated with increased mortality but only in preterm infants born small for gestational age (SGA) (Di Fiore et al., 2017). Growth restriction has been shown to alter development of respiratory chemoreceptors (Harding et al., 2000), and increase the risk of pulmonary hypertension in the setting of BPD (Check et al., 2013). In addition, hypoxia induced pulmonary vasoconstriction is markedly exaggerated in lambs with pulmonary hypertension (Lakshminrusimha et al., 2009). Therefore, IH during early postnatal life may exacerbate pulmonary hypertension in SGA infants putting them at increased risk for death. Central sleep apnea, as a surrogate for IH, is also associated with increased mortality in hospitalized infants with congenital heart disease(Combs et al., 2018). Taken together these studies suggest a complex interplay between specific patterns of IH, and endogenous (ie pulmonary hypertension, growth restriction) and exogenous factors (ie respiratory support, supplemental oxygen) putting the infant at greater risk for poor outcomes.

Interestingly, there are data that suggest that not all IH may be pathologic. For example, “mild” intermittent hypoxia is currently being investigated as a therapeutic intervention for spinal cord injury (Navarrete-Opazo et al., 2017) based on the idea that “mild” fluctuations of low oxygen induce growth factors without the accompanying potential detrimental side effects such as inflammation and oxidative stress. The definition of “mild” has yet to be determined and suggests that identifying at risk from benign patterns of IH is imperative for clinical care, especially since the use of supplemental oxygen to treat these events is, in and of itself, a risk factor for morbidity in preterm infants.

3. Oxidative Stress biomarkers relevant to Newborn Medicine

Aerobic metabolism is indispensable for the survival of multicellular organisms. Combustion of energy containing basic nutritional elements in the presence of oxygen is substantially more efficient from an energetic perspective. Hence, while anaerobic metabolism leads to the production of 2–4 mol of ATP per mol of glucose, aerobic metabolism will render 18–20 times more efficient. Oxyregulator tissues such as myocardium and the Central Nervous System are highly dependent on oxygen for their biologic activities, growth, development and survival.(Saugstad et al., 2018)

Oxygen is present in nature as dioxygen. Complete reduction of oxygen requires 4 electrons to complete its outer shell. This is mostly accomplished in the mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain coupled to the Krebs’s cycle. However, 2–3% of oxygen is only partially reduced under physiologic circumstances with just one electron leading to the formation of superoxide anion [•O−2], a highly reactive oxygen species and free radical. Superoxide is immediately dismutated by the action of the family of Superoxide Dismutases (SOD) to form hydrogen peroxide [H2O2], a reactive oxygen species non-free radical [Figure 1]. Hydrogen peroxide acts fundamentally as an extremely relevant biological cell signaling molecule. However, in the presence of transition metals such as copper, manganese, selenium and especially iron, Fenton chemistry ensues and hydrogen peroxide combined with ferrous iron leads to the formation of hydroxyl radical [HO•] a highly reactive powerful non-selective free radical capable of causing damage to cell components such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, or nucleic acids. Hydrogen peroxide, however, is reduced to water in the presence of glutathione peroxidases (GPx) and Catalases (CAT) thus avoiding its conversion into hydroxyl radical. In this reaction 2 mol of reduced glutathione [GSH] confer their electrons and get transformed into one mol of oxidized glutathione [GSSG]. In the presence of NADH and Glutathione Reductase, GSSG is reverted back to 2 mol GSH. Finally, superoxide anion can also combine with nitric oxide [NO•] to form highly reactive peroxynitrite [ONOO•]. Peroxynitrite is an oxidant and nitrating agent and can also damage a wide array of molecules in cells including lipids, DNA and proteins (Sies et al., 2017).

Reactive oxygen species have an extremely short half-life; hence, superoxide anion reacts with nearby molecules at rates near the diffusion limit (meaning rates near those at which molecules encounter each other) of 1010mol−1 1s−1 rendering its determination by analytical methods in the clinical setting unattainable (Kehrer and Klotz, 2015). In the experimental setting, the measurement of oxygen-centered free radical generation in biological systems is preferably performed using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy techniques. EPR, also known as electron spin resonance, is capable of detecting molecules with unpaired electrons. When combined with an appropriate spin trap, it is a powerful and reliable technique to unequivocally measure superoxide anion, hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide derived free radicals (Griendling et al., 2016). Nevertheless, this invasive and complex technique is not applicable to clinical research or practice. Alternatively, indirect measurement of oxidative stress has been implemented. Hence, activity of antioxidant enzymes, level of non-enzymatic antioxidants, or oxidative damage caused to biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids have been successfully employed to assess free radical aggression to tissue in a great variety of acute and chronic conditions (Kehrer and Klotz, 2015) and recently in the neonatal period (Millan et al., 2018).

3.1. Biomarkers employed in the neonatal period

3.1.1. Ratio of Reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG)

The GSH/GSSG ratio is probably the only comprehensive biomarker employed in newborn medicine. Glutathione is the most abundant non-enzymatic antioxidant present in the cytoplasm and the reduced to oxidized glutathione ratio regulates the cytoplasmic redox status equilibrium which is essential for cell reproduction, growth, differentiation and death (Schafer and Buettner, 2001). Recently, a method of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to mass spectrometry (MS/MS) has been validated in whole blood of newborn infants. The peculiarity of GSH/GSSG determination resides in the fact that it has to be determined in whole blood because GSH is mostly within the erythrocytes and GSSG is free in plasma; moreover, blood has to be acidified and auto-oxidation blocked by the addition of N-ethylmaleimide (Escobar et al., 2016). Based on surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) a new method has been developed to accurately measure GSH. GSH is measured adding a silver colloid to the blood sample to enhance the GSH spectrometric signal and thus needing only very small volumes (20μL) of blood (Sanchez-Illana et al., 2018a).

3.1.2. Protein oxidation

A series of amino acidic residues of proteins can undergo structural and functional modifications through the action of free radicals. The most employed biomarker in the neonatal period relies on the oxidation of Phenylalanine (Phe) residues in proteins. The reaction of Phe residues with hydroxyl radicals converts Phe into ortho-tyrosine (o-Tyr) or meta-tyrosine (m-Tyr); both residues are not physiologically produced in nature since Phe metabolization leads physiologically to the production of para-tyrosine (p-Tyr). Of note, p-Tyr is nitratrated by the action of peroxynitrite to form 3-nitro-tyrosine (3NO2-Tyr) which is a specific biomarker of protein nitration (Tsikas, 2012). Neutrophils and macrophages produce considerable amounts of hypochlorous acid in the presence of myeloperoxidase to attack bacteria. The reaction of hypochlorous acid with p-Tyr leads to the formation of 3-chlorotyrosine (3Cl-tyr) a useful marker of inflammation (Torres-Cuevas et al., 2016b)). Results of Phe oxidation are expressed as ratios such as o-Tyr/Phe, m-Tyr/Phe, 3NO2-Tyr/p-Tyr, and 3Cl-Tyr/P-Tyr. These biomarkers have been widely employed in neonatology and HPLC-MS/MS methods for their determination in a variety of matrices such as amniotic fluid, urine, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, or human milk (Solberg et al., 2007; Vento et al., 2009) (Sanchez-Illana et al., 2018b; Torres-Cuevas et al., 2014).

3.1.3. DNA oxidation

Under normal conditions, ongoing oxidative stress generated by cell metabolism causes damage especially to guanine but also pyrimidine bases of DNA in the form of nucleotide oxidation, strand breakage, loss of bases and adduct formation. However, specific DNA enzymatic mechanisms actively and continuously repair damaged DNA reverting the situation and avoiding the perpetuation of mutations (Strauss, 2018; Wood et al., 2005). The most widely employed biomarkers of DNA in clinical medicine are the byproducts of guanine oxidation and specifically 7,8-hydroxy-2’ deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG or 8-OHdG). Validated HPLC-MS/MS have been developed to measure these metabolites in amniotic fluid, urine, plasma, CSF, etc. of newborn babies (Escobar et al., 2013; Ledo et al., 2009; Sanchez-Illana et al., 2018b; Solberg et al., 2007).

3.1.4. Lipids

Under physiologic circumstances, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are peroxidized by specific enzymes such as lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase leading to the synthesis of prostaglandins, prostacyclin, thromboxane, leukotrienes and lipoxins. However, in a pro-oxidant situation PUFA can be directly oxidized by free radicals, especially hydroxyl radicals, and form specific byproducts such as isoprostanes (IsoPs), isofurans (IsoFs), dihomo-isoprostanes (Dihomo-IsoPs), neuroprostanes (NeuroPs) and neurofurans (NeurFs) (Kuligowski et al., 2014).

These byproducts of lipid peroxidation are to date considered the most reliable biomarkers of lipid peroxidation. Moreover, Dihomo-IsoPs, NeuroPs, and NeuroFs are highly specific reflecting brain damage (Milne et al., 2015) (Solberg et al., 2012). HPLC-MS/MS and gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GS-MS/MS) methods have been validated in the lab and in clinical studies in the neonatal period (Chafer-Pericas et al., 2016; Galano et al., 2017).

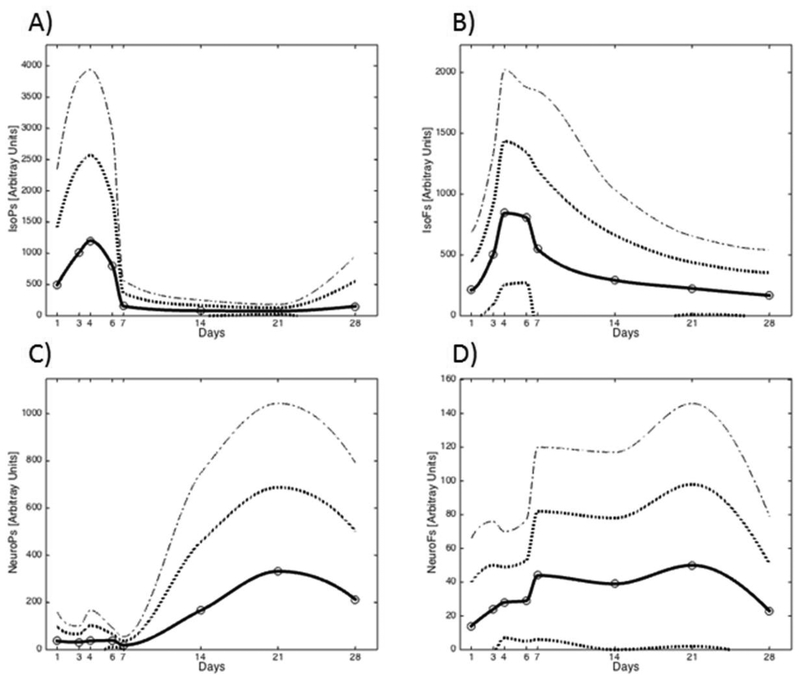

3.2. Normal ranges for lipid peroxidation biomarkers in preterm

Despite an abundant literature in the field of oxidative metabolism in the neonatal period information on normal ranges of the most employed oxidative and nitrosative biomarkers is lacking(Buonocore et al., 2017; Millan et al., 2018; Torres-Cuevas et al., 2017). The difficulties reside in the fact that normal controls are not generally available and comparisons are made between preterm infants submitted to different interventions. Kuligowski et al (Kuligowski et al., 2015), have published a reference range for urinary lipid peroxidation biomarkers in healthy preterm infants during the newborn period using high-throughput ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) method. Biomarkers included IsoPs, IsoFs, NeuroPs and NeuroPs plotted in a centile graph that comprised the first 4 weeks after birth. [Figure 4]

Figure 4.

-Reference range of urinary lipid peroxidation byproducts in preterm infants ≤28 weeks gestation with a clinical course free of oxidative stress-associated complications. Analytical determinations were performed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Straight line-mean values, dotted lines-Standard Deviations. Copyright, used with permission, Kuligowski J, et al. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015

3.3. Environmental factors and conditions leading to pro-oxidant status in neonates

3.3.1. Hypoxia/ischemia and reperfusion injury

During fetal to neonatal transition intermittent periods of hypoxia-ischemia occur. However, under certain circumstances such as birth asphyxia intense and prolonged hypoxia and/or ischemia reduce oxygen and glucose supply to neuronal cells and subsequently may lead to the exhaustion of ATP. As a consequence, there is an inactivation of ATP-dependent ion pumps causing intracellular accumulation of Na+ (cell swelling), ionized Ca++ (increased free radical formation) and excitotoxicity (inhibition of recaptation of neurotransmitters at the synaptic cleft). If this pathologic situation persists long enough it will lead to cell death (Douglas-Escobar and Weiss, 2015).

Reperfusion injury occurs in oxygen deprived tissues following restoration of blood flow and oxygen supply. The burst of free radicals occurring upon reoxygenation is greatly related to the conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase (XD) into xanthine oxidase (XO). XD is unable to transfer electrons to molecular oxygen, although it uses NADPH as electron acceptor. The conversion of XD to XO involves either the oxidation of the thiol groups, especially GSH to GSSG, L-cysteine to cysteine, or proteolysis by activated proteases as an adaptive mechanism for Ca2+ transport in energy-deficient cells. Upon re-oxygenation XO converts hypoxanthine to uric acid and molecular oxygen to superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. In addition, transition metals (e.g., iron) precipitate the generation of hydroxyl radical via Fenton chemistry thus increasing oxidative damage exponentially (Granger and Kvietys, 2015).

Other sources of free radicals upon reoxygenation are NADPH oxidase activation upon supplementation with oxygen and activation of nitric oxide synthase with production of nitric oxide and subsequent increased generation of peroxynitrite and nitrosative stress (Torres-Cuevas et al., 2017). Finally, upon reoxygenation, in an experimental model increased succinate accumulated during hypoxia in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) triggers a reverse electron flow from Complex-II to Complex-I generating a many-fold increased production of ROS compared to the conventional forward electron transport from Complex-I to Complex-II (Sahni et al., 2018). In patients with severe asphyxia, Sanchez-Illana et al., showed that during reperfusion there is a transient shift from complex I-dependent oxidation of NADH towards complex II-linked oxidation of succinate in the brain mitochondria. As a consequence, electron transport in the ETC is reversed, causing a substantial increase of ROS production (Sanchez-Illana et al., 2017)).

3.3.2. Oxygen supplementation

Lung matures late in gestation. Therefore, very preterm infants frequently need ventilatory support and oxygen supplementation in the first days after birth or even longer(Torres-Cuevas et al., 2016a). Experimental studies have documented that antioxidant enzymes are not expressed until late in gestation following a similar pattern to surfactant synthesis in the type II pneumocytes (Frank and Groseclose, 1984; Frank and Sosenko, 1987). Similarly, studies performed in very preterm human neonates have reported an immature antioxidant response when confronted with pro-oxidant circumstances, especially oxygen supplementation in the delivery room (Bhandari, 2010; Vento, 2014). Under these circumstances a pro-oxidant status can result in damage to lung (ie BPD (Kuligowski et al., 2015), brain and retina and constitute the “free radical disease of prematurity” (Saugstad et al., 2012).

3.3.3. Parenteral Nutrition

Extremely preterm infants require full parenteral nutrition in the first days after birth due to the immaturity of the gastrointestinal system to satisfy metabolic, growth and developmental needs (Tyson and Kennedy, 2005). However, parenteral solutions are an important source of oxidants. The effect of phototoxicity upon specific components such as amino acids, ascorbic acid, multivitamin solutions and lipids leads to the formation of reactive chemical species such as hydrogen peroxide, organic lipoperoxides, and ascorbyl-peroxide (Chessex et al., 2017). These oxidation by-products have deleterious effects upon preterm infants especially damaging the lung and liver. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis revealed that shielding parenteral nutrition from light significantly diminishes the negative effects (ie. mortality) of these pro-oxidant byproducts (OR:0.53; [CI 0.32, 0.87]) (Chessex et al., 2017).

3.3.4. Sepsis

Despite improvement in newborn care in the modern NICUs, early and late onset sepsis in extremely preterm infants is still frequent and constitutes globally one of the most relevant causes of mortality and short-and-long term morbidities (Liu et al., 2016). The inflammatory cascade triggered by infection in the neonatal period leads to changes in the gene expression with activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6 and IL-8. Pro-inflammatory cytokines in turn cause activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB) that translocates to the nucleus and activates oxidative stress-related pathways leading to the generation of a burst of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and subsequent tissue damage and mitochondrial impairment (Poggi and Dani, 2018)[Figure 5]. Cernada et al., showed that sepsis in preterm infants prompts the induction of genes related to proinflammatory and prooxidant pathways in desquamated intestinal cells. Oxidative stress and inflammation induced a shift in the intestinal microbiome towards the predominance of Enterobacteria and reduction of Bacteroides and Bifidobacteria. These changes in the microbiome may predispose to further complications such as necrotizing enterocolitis (Cernada et al., 2016)

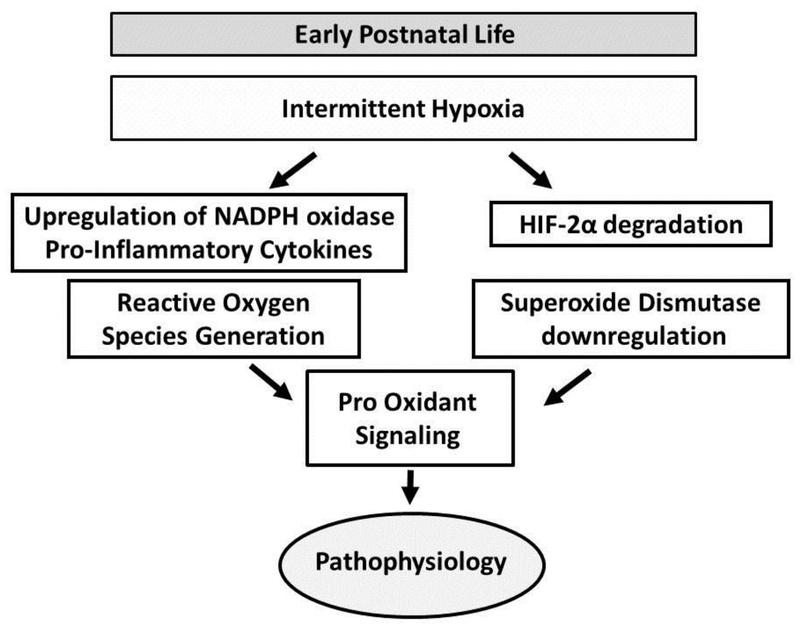

Figure 5.

-In rodents, IH upregulates NADPH oxidase and pro-inflammatory cytokines leading to generation of reactive oxygen species (Yuan et al., 2008). IH also downregulates HIF-2α in carotid bodies and adrenal medullae leading to inhibition of SOD2 transcription (Nanduri et al., 2009). This increase in reactive oxygen species superimposed on decreased anti-oxidant signaling may result in overall increased oxidative stress inducing a pathological cascade.

4. Intermittent Hypoxia/Hypoxemia and Reactive Oxygen Species

Although the mechanism by which IH induces a pathological cascade is unknown, potential causal pathways include alterations in inflammation (Del Rio et al., 2011) and/or reactive oxygen species (Yang et al., 2016). For example, in rodents, IH induces HIF-1α accumulation due to generation of reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase (Yuan et al., 2008). IH also downregulates HIF-2α in carotid bodies and adrenal medullae leading to inhibition of SOD2 transcription (Nanduri et al., 2009) [Figure 5]. Thus, IH initiates reactive oxygen species superimposed on decreased anti-oxidant signaling resulting in an overall increase in oxidative stress.

Chronic intermittent hypoxemia exposure in subjects with sleep apnea is also known to produce oxidative stress (Jelic et al., 2008) and results in an array of significant oxidative injuries in sleep-wake regions of the brain (Veasey, 2009). Similarly, neonatal rodents exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia exhibit an enhanced hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) in conjunction with a robust increase in carotid body nitro-tyrosine production(Morgan et al., 2016). The enhanced ventilatory response returned to baseline levels with administration of apocynin (NADPH oxidase inhibitor). There are currently no direct data linking IH with ROS in preterm infants but preterm infants with a greater frequency of apnea also exhibit a significantly higher ventilatory response to acute HVR, thus IH may play a role in peripheral chemoreceptor sensitivity (Nock et al., 2004) through a similar pathway.

Increased formation of reactive oxygen species occurs during the reoxygenation phase (Fabian et al., 2004) signifying that timing and intensity of IH may be an important contributor for a pathological cascade. For example, rats exposed to hypoxia exhibited an increase in cortical surface superoxide anion levels during the recovery period that returns back to baseline after 20 minutes (Fabian et al., 2004). Interestingly, the relationship between IH and both BPD and ROP in preterm infants was restricted to IH events occurring 1–20 minutes apart (Di Fiore et al., 2012; Raffay et al., 2018). These tightly clustered IH events may be initiating excessive reactive oxygen species induced angiogenesis leading to neovascularization (Kim and Byzova, 2014) and may be one explanation why brief clustered (10min apart) versus dispersed (2hr) hypoxic exposures results in more severe oxygen induced retinopathy(Coleman et al., 2008).

Not all IH induced alterations in reactive oxygen species may be detrimental. For example, in mice, neonatal exposure to “modest” intermittent hypoxia has been associated with enhanced spatial learning and memory, increased DNS concentrations, neurogenesis and expression of proteins involved with synaptic plasticity (Navarrete-Opazo and Mitchell, 2014). This may be one explanation why the relationship between IH and neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants was limited to IH events that were >1 min in duration (Poets et al., 2015) and IH and ROP was restricted to IH occurring 1–20 min apart (Di Fiore et al., 2012). We are only beginning to appreciate that the beneficial versus detrimental effects of various patterns of IH may follow a continuous spectrum. Future studies in preterm infants are needed to address the specific patterns of IH that distinguish pathological from benign or even beneficial cascades.

Highlights.

Intermittent hypoxemia events (IH) in extremely preterm infants progressively increase in frequency during the first few months of life

IH during early postnatal life are associated with multiple poor outcomes including retinopathy of prematurity, neurodevelopmental impairment, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and mortality

There are multiple pathways in which IH can cause poor outcomes including initiation of a pathological oxidative stress induced cascade

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abu Jawdeh EG, Martin RJ, Dick TE, Walsh MC, Di Fiore JM, 2014. The effect of red blood cell transfusion on intermittent hypoxemia in ELBW infants. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 34, 921–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancalari E, Claure N, 2013. The evidence for non-invasive ventilation in the preterm infant. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 98, F98–F102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancalari E, Claure N, 2018. Respiratory Instability and Hypoxemia Episodes in Preterm Infants. American journal of perinatology 35, 534–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R, 2007. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiological reviews 87, 1215–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari V, 2010. Hyperoxia-derived lung damage in preterm infants. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 15, 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block K, Gorin Y, 2012. Aiding and abetting roles of NOX oxidases in cellular transformation. Nature reviews. Cancer 12, 627–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann PE, Wiechers C, Pantalitschka T, Diebold J, Vagedes J, Poets CF, 2013. Under-recognition of alarms in a neonatal intensive care unit. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 98, F524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore G, Perrone S, Tataranno ML, 2017. Oxidative Stress in the Newborn. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2017, 1094247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernada M, Bauerl C, Serna E, Collado MC, Martinez GP, Vento M, 2016. Sepsis in preterm infants causes alterations in mucosal gene expression and microbiota profiles compared to non-septic twins. Scientific reports 6, 25497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafer-Pericas C, Torres-Cuevas I, Sanchez-Illana A, Escobar J, Kuligowski J, Solberg R, Garberg HT, Huun MU, Saugstad OD, Vento M, 2016. Development of a reliable analytical method to determine lipid peroxidation biomarkers in newborn plasma samples. Talanta 153, 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Check J, Gotteiner N, Liu X, Su E, Porta N, Steinhorn R, Mestan KK, 2013. Fetal growth restriction and pulmonary hypertension in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 33, 553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessex P, Laborie S, Nasef N, Masse B, Lavoie JC, 2017. Shielding Parenteral Nutrition From Light Improves Survival Rate in Premature Infants. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 41, 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RJ, Beharry KD, Brock RS, Abad-Santos P, Abad-Santos M, Modanlou HD, 2008. Effects of brief, clustered versus dispersed hypoxic episodes on systemic and ocular growth factors in a rat model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Pediatric research 64, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs D, Skrepnek G, Seckeler MD, Barber BJ, Morgan WJ, Parthasarathy S, 2018. Sleep-Disordered Breathing is Associated With Increased Mortality in Hospitalized Infants With Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 14, 1551–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Fleck BW, Elton RA, McIntosh N, 1995. Transcutaneous oxygen levels in retinopathy of prematurity. Lancet 346, 1464–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JA, Bastrenta P, Cavigioli F, Thio M, Ong T, Siew ML, Hooper SB, Davis PG, 2014. The precision and accuracy of Nellcor and Masimo oximeters at low oxygen saturations (70%) in newborn lambs. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 99, F278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MJ, Hue GE, Caudle WM, Miller GW, Keating GL, Rye DB, 2003. Episodic neonatal hypoxia evokes executive dysfunction and regionally specific alterations in markers of dopamine signaling. Neuroscience 117, 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MJ, Jones KA, Solomon IG, Keating GL, Rye DB, 2005. Reduced extracellular dopamine and increased responsiveness to novelty: neurochemical and behavioral sequelae of intermittent hypoxia. Sleep 28, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio R, Moya EA, Iturriaga R, 2011. Differential expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, endothelin-1 and nitric oxide synthases in the rat carotid body exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Brain research 1395, 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore JM, Bloom JN, Orge F, Schutt A, Schluchter M, Cheruvu VK, Walsh M, Finer N, Martin RJ, 2010. A higher incidence of intermittent hypoxemic episodes is associated with severe retinopathy of prematurity. The Journal of pediatrics 157, 69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore JM, Dylag AM, Honomichl RD, Hibbs AM, Martin RJ, Tatsuoka C, Raffay TM, 2018. Early inspired oxygen and intermittent hypoxemic events in extremely premature infants are associated with asthma medication use at 2 years of age. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore JM, Kaffashi F, Loparo K, Sattar A, Schluchter M, Foglyano R, Martin RJ, Wilson CG, 2012. The relationship between patterns of intermittent hypoxia and retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants. Pediatric research 72, 606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore JM, Martin RJ, Li H, Morris N, Carlo WA, Finer N, Walsh M, 2017. Patterns of Oxygenation, Mortality, and Growth Status in the Surfactant Positive Pressure and Oxygen Trial Cohort. The Journal of pediatrics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Escobar M, Weiss MD, 2015. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review for the clinician. JAMA pediatrics 169, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dylag AM, Mayer CA, Raffay TM, Martin RJ, Jafri A, MacFarlane PM, 2017. Long-term effects of recurrent intermittent hypoxia and hyperoxia on respiratory system mechanics in neonatal mice. Pediatric research 81, 565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emancipator JL, Storfer-Isser A, Taylor HG, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Johnson NL, Zambito AM, Redline S, 2006. Variation of cognition and achievement with sleep-disordered breathing in full-term and preterm children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 160, 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Sanchez-Illana A, Kuligowski J, Torres-Cuevas I, Solberg R, Garberg HT, Huun MU, Saugstad OD, Vento M, Chafer-Pericas C, 2016. Development of a reliable method based on ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry to measure thiol-associated oxidative stress in whole blood samples. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 123, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Teramo K, Stefanovic V, Andersson S, Asensi MA, Arduini A, Cubells E, Sastre J, Vento M, 2013. Amniotic fluid oxidative and nitrosative stress biomarkers correlate with fetal chronic hypoxia in diabetic pregnancies. Neonatology 103, 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian RH, Perez-Polo JR, Kent TA, 2004. Extracellular superoxide concentration increases following cerebral hypoxia but does not affect cerebral blood flow. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience 22, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild K, Mohr M, Paget-Brown A, Tabacaru C, Lake D, Delos J, Moorman JR, Kattwinkel J, 2016. Clinical associations of immature breathing in preterm infants: part 1-central apnea. Pediatric research 80, 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild KD, Nagraj VP, Sullivan BA, Moorman JR, Lake DE, 2018. Oxygen desaturations in the early neonatal period predict development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatric research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Groseclose EE, 1984. Preparation for birth into an O2-rich environment: the antioxidant enzymes in the developing rabbit lung. Pediatric research 18, 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Sosenko IR, 1987. Prenatal development of lung antioxidant enzymes in four species. The Journal of pediatrics 110, 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano JM, Lee YY, Oger C, Vigor C, Vercauteren J, Durand T, Giera M, Lee JC, 2017. Isoprostanes, neuroprostanes and phytoprostanes: An overview of 25years of research in chemistry and biology. Progress in lipid research 68, 83–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Daniel JM, Dohanich GP, 2001a. Behavioral and anatomical correlates of chronic episodic hypoxia during sleep in the rat. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 21, 2442–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal E, Row BW, Schurr A, Gozal D, 2001b. Developmental differences in cortical and hippocampal vulnerability to intermittent hypoxia in the rat. Neuroscience letters 305, 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DN, Kvietys PR, 2015. Reperfusion injury and reactive oxygen species: The evolution of a concept. Redox biology 6, 524–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling KK, Touyz RM, Zweier JL, Dikalov S, Chilian W, Chen YR, Harrison DG, Bhatnagar A, 2016. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species, Reactive Nitrogen Species, and Redox-Dependent Signaling in the Cardiovascular System: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation research 119, e39–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman M, Bry K, Hoppu K, Lappi M, Pohjavuori M, 1992. Inositol supplementation in premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 326, 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Tester ML, Moss TJ, Davey MG, Louey S, Joyce B, Hooper SB, Maritz G, 2000. Effects of intra-uterine growth restriction on the control of breathing and lung development after birth. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology 27, 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett ME, 2010. The effects of oxygen stresses on the development of features of severe retinopathy of prematurity: knowledge from the 50/10 OIR model. Documenta ophthalmologica. Advances in ophthalmology 120, 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt CE, Corwin MJ, Baird T, Tinsley LR, Palmer P, Ramanathan R, Crowell DH, Schafer S, Martin RJ, Hufford D, Peucker M, Weese-Mayer DE, Silvestri JM, Neuman MR, Cantey-Kiser J, 2004. Cardiorespiratory events detected by home memory monitoring and one-year neurodevelopmental outcome. The Journal of pediatrics 145, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola JJ, Ahmed P, Ieromnimon A, Goepfert P, Laiou E, Quansah R, Jaakkola MS, 2006. Preterm delivery and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 118, 823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier A, Khairy M, Kokkotis A, Cormier C, Messmer D, Barrington KJ, 2004. Apnea is associated with neurodevelopmental impairment in very low birth weight infants. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 24, 763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelic S, Padeletti M, Kawut SM, Higgins C, Canfield SM, Onat D, Colombo PC, Basner RC, Factor P, LeJemtel TH, 2008. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and repair capacity of the vascular endothelium in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 117, 2270–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer JP, Klotz LO, 2015. Free radicals and related reactive species as mediators of tissue injury and disease: implications for Health. Critical reviews in toxicology 45, 765–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YW, Byzova TV, 2014. Oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood 123, 625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowski J, Aguar M, Rook D, Lliso I, Torres-Cuevas I, Escobar J, Quintas G, Brugada M, Sanchez-Illana A, van Goudoever JB, Vento M, 2015. Urinary Lipid Peroxidation Byproducts: Are They Relevant for Predicting Neonatal Morbidity in Preterm Infants? Antioxidants & redox signaling 23, 178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowski J, Escobar J, Quintas G, Lliso I, Torres-Cuevas I, Nunez A, Cubells E, Rook D, van Goudoever JB, Vento M, 2014. Analysis of lipid peroxidation biomarkers in extremely low gestational age neonate urines by UPLC-MS/MS. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 406, 4345–4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminrusimha S, Swartz DD, Gugino SF, Ma CX, Wynn KA, Ryan RM, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH, 2009. Oxygen concentration and pulmonary hemodynamics in newborn lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Pediatric research 66, 539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledo A, Arduini A, Asensi MA, Sastre J, Escrig R, Brugada M, Aguar M, Saenz P, Vento M, 2009. Human milk enhances antioxidant defenses against hydroxyl radical aggression in preterm infants. The American journal of clinical nutrition 89, 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Mathers C, Black RE, 2016. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 388, 3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankouski A, Kantores C, Wong MJ, Ivanovska J, Jain A, Benner EJ, Mason SN, Tanswell AK, Auten RL, Jankov RP, 2017. Intermittent hypoxia during recovery from neonatal hyperoxic lung injury causes long-term impairment of alveolar development: A new rat model of BPD. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 312, L208–L216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy C, Durand M, Hewlett V, 1993. Episodes of spontaneous desaturations in infants with chronic lung disease at two different levels of oxygenation. Pediatric pulmonology 15, 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan I, Pinero-Ramos JD, Lara I, Parra-Llorca A, Torres-Cuevas I, Vento M, 2018. Oxidative Stress in the Newborn Period: Useful Biomarkers in the Clinical Setting. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne GL, Dai Q, Roberts LJ 2nd, 2015. The isoprostanes−-25 years later. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1851, 433–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BJ, Bates ML, Rio RD, Wang Z, Dopp JM, 2016. Oxidative stress augments chemoreflex sensitivity in rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology 234, 47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanduri J, Wang N, Yuan G, Khan SA, Souvannakitti D, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Garcia JA, Prabhakar NR, 2009. Intermittent hypoxia degrades HIF-2alpha via calpains resulting in oxidative stress: implications for recurrent apnea-induced morbidities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 1199–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Opazo A, Alcayaga J, Sepulveda O, Rojas E, Astudillo C, 2017. Repetitive Intermittent Hypoxia and Locomotor Training Enhances Walking Function in Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury Subjects: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of neurotrauma 34, 1803–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Opazo A, Mitchell GS, 2014. Therapeutic potential of intermittent hypoxia: a matter of dose. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 307, R1181–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock ML, Difiore JM, Arko MK, Martin RJ, 2004. Relationship of the ventilatory response to hypoxia with neonatal apnea in preterm infants. The Journal of pediatrics 144, 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn JS, Henry MM, Wall PT, Tolman BL, 1995. The range of PaO2 variation determines the severity of oxygen-induced retinopathy in newborn rats. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 36, 2063–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillekamp F, Hermann C, Keller T, von Gontard A, Kribs A, Roth B, 2007. Factors influencing apnea and bradycardia of prematurity-implications for neurodevelopment. Neonatology 91, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poets CF, Roberts RS, Schmidt B, Whyte RK, Asztalos EV, Bader D, Bairam A, Moddemann D, Peliowski A, Rabi Y, Solimano A, Nelson H, 2015. Association Between Intermittent Hypoxemia or Bradycardia and Late Death or Disability in Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 314, 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggi C, Dani C, 2018. Sepsis and Oxidative Stress in the Newborn: From Pathogenesis to Novel Therapeutic Targets. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2018, 9390140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quine D, Stenson BJ, 2009. Arterial oxygen tension (Pao2) values in infants <29 weeks of gestation at currently targeted saturations. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 94, F51–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffay TM, Dylag AM, Sattar A, Abu Jawdeh EG, Cao S, Pax BM, Loparo KA, Martin RJ, Di Fiore JM, 2018. Neonatal intermittent hypoxemia events are associated with diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Pediatric research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner V, Kishkurno SV, Slinko SK, Sosunov SA, Sosunov AA, Polin RA, Ten VS, 2007. The contribution of intermittent hypoxemia to late neurological handicap in mice with hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Neonatology 92, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner V, Starkov A, Matsiukevich D, Polin RA, Ten VS, 2009. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to alveolar developmental arrest in hyperoxia-exposed mice. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 40, 511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosychuk RJ, Hudson-Mason A, Eklund D, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, 2012. Discrepancies between arterial oxygen saturation and functional oxygen saturation measured with pulse oximetry in very preterm infants. Neonatology 101, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni PV, Zhang J, Sosunov S, Galkin A, Niatsetskaya Z, Starkov A, Brookes PS, Ten VS, 2018. Krebs cycle metabolites and preferential succinate oxidation following neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in mice. Pediatric research 83, 491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Illana A, Mayr F, Cuesta-Garcia D, Pineiro-Ramos JD, Cantarero A, Guardia M, Vento M, Lendl B, Quintas G, Kuligowski J, 2018a. On-Capillary Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Determination of Glutathione in Whole Blood Microsamples. Analytical chemistry 90, 9093–9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Illana A, Nunez-Ramiro A, Cernada M, Parra-Llorca A, Valverde E, Blanco D, Moral-Pumarega MT, Cabanas F, Boix H, Pavon A, Chaffanel M, Benavente-Fernandez I, Tofe I, Loureiro B, Fernandez-Lorenzo JR, Fernandez-Colomer B, Garcia-Robles A, Kuligowski J, Vento M, 2017. Evolution of Energy Related Metabolites in Plasma from Newborns with Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy during Hypothermia Treatment. Scientific reports 7, 17039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Illana A, Parra-Llorca A, Escuder-Vieco D, Pallas-Alonso CR, Cernada M, Gormaz M, Vento M, Kuligowski J, 2018b. Biomarkers of oxidative stress derived damage to proteins and DNA in human breast milk. Analytica chimica acta 1016, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SA, Edwards BA, Kelly VJ, Skuza EM, Davidson MR, Wilkinson MH, Berger PJ, 2010. Mechanism underlying accelerated arterial oxygen desaturation during recurrent apnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 182, 961–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad OD, Oei JL, Lakshminrusimha S, Vento M, 2018. Oxygen therapy of the newborn from molecular understanding to clinical practice. Pediatric research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad OD, Sejersted Y, Solberg R, Wollen EJ, Bjoras M, 2012. Oxygenation of the newborn: a molecular approach. Neonatology 101, 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer FQ, Buettner GR, 2001. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free radical biology & medicine 30, 1191–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher RE, Farrell PM, Olson EB Jr., 1987. Circulating 5-hydroxytryptamine concentrations in preterm newborns. Pediatric pulmonology 3, 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H, Berndt C, Jones DP, 2017. Oxidative Stress. Annual review of biochemistry 86, 715–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg R, Andresen JH, Escrig R, Vento M, Saugstad OD, 2007. Resuscitation of hypoxic newborn piglets with oxygen induces a dose-dependent increase in markers of oxidation. Pediatric research 62, 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg R, Longini M, Proietti F, Vezzosi P, Saugstad OD, Buonocore G, 2012. Resuscitation with supplementary oxygen induces oxidative injury in the cerebral cortex. Free radical biology & medicine 53, 1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood BG, McLaughlin K, Cortez J, 2015. Near-infrared spectroscopy: applications in neonates. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 20, 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss BS, 2018. Why Is DNA Double Stranded? The Discovery of DNA Excision Repair Mechanisms. Genetics 209, 357–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HG, Klein N, Schatschneider C, Hack M, 1998. Predictors of early school age outcomes in very low birth weight children. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP 19, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cuevas I, Cernada M, Nunez A, Escobar J, Kuligowski J, Chafer-Pericas C, Vento M, 2016a. Oxygen Supplementation to Stabilize Preterm Infants in the Fetal to Neonatal Transition: No Satisfactory Answer. Frontiers in pediatrics 4, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cuevas I, Kuligowski J, Carcel M, Chafer-Pericas C, Asensi M, Solberg R, Cubells E, Nunez A, Saugstad OD, Vento M, Escobar J, 2016b. Protein-bound tyrosine oxidation, nitration and chlorination by-products assessed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Analytica chimica acta 913, 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cuevas I, Kuligowski J, Escobar J, Vento M, 2014. Determination of biomarkers of protein oxidation in tissue and plasma. Free radical biology & medicine 75 Suppl 1, S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cuevas I, Parra-Llorca A, Sanchez-Illana A, Nunez-Ramiro A, Kuligowski J, Chafer-Pericas C, Cernada M, Escobar J, Vento M, 2017. Oxygen and oxidative stress in the perinatal period. Redox biology 12, 674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas D, 2012. Analytical methods for 3-nitrotyrosine quantification in biological samples: the unique role of tandem mass spectrometry. Amino acids 42, 45–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson JE, Kennedy KA, 2005. Trophic feedings for parenterally fed infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD000504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagedes J, Poets CF, Dietz K, 2013. Averaging time, desaturation level, duration and extent. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 98, F265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veasey S, 2009. Insight from animal models into the cognitive consequences of adult sleep-disordered breathing. ILAR journal / National Research Council, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources 50, 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vento M, 2014. Oxygen supplementation in the neonatal period: changing the paradigm. Neonatology 105, 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vento M, Moro M, Escrig R, Arruza L, Villar G, Izquierdo I, Roberts LJ 2nd, Arduini A, Escobar JJ, Sastre J, Asensi MA, 2009. Preterm resuscitation with low oxygen causes less oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 124, e439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werdich XQ, McCollum GW, Rajaratnam VS, Penn JS, 2004. Variable oxygen and retinal VEGF levels: correlation with incidence and severity of pathology in a rat model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Experimental eye research 79, 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RD, Mitchell M, Lindahl T, 2005. Human DNA repair genes, 2005. Mutation research 577, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Shen YJ, Lai CJ, Kou YR, 2016. Inflammatory Role of ROS-Sensitive AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in the Hypersensitivity of Lung Vagal C Fibers Induced by Intermittent Hypoxia in Rats. Frontiers in physiology 7, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York JR, Landers S, Kirby RS, Arbogast PG, Penn JS, 2004. Arterial oxygen fluctuation and retinopathy of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight infants. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 24, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Nanduri J, Khan S, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR, 2008. Induction of HIF-1alpha expression by intermittent hypoxia: involvement of NADPH oxidase, Ca2+ signaling, prolyl hydroxylases, and mTOR. Journal of cellular physiology 217, 674–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]