Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES:

Limited studies suggest lower extremity (LE) fractures are morbid events for nursing home (NH) residents. Our objective was to conduct a nationwide study comparing the incidence and resident characteristics associated with hip (proximal femur) versus non-hip LE (femoral shaft and tibia-fibula) fractures in the NH.

DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING:

U.S. NHs.

PARTICIPANTS:

We included all long-stay residents aged ≥65 years enrolled in Medicare 1/1/2008-12/31/2009 (N=1,257,279). Residents were followed from long-stay qualification until the first event of LE fracture, death, or end of follow-up (2-years).

MEASUREMENTS:

Fractures were classified using Medicare diagnostic and procedural codes. Function, cognition, and medical status were obtained from the Minimum Data Set prior to long-stay qualification. Incidence rates (IR) were calculated as the total number of fractures divided by person-years.

RESULTS:

During 42,800 person-years follow-up, 52,177 residents had a LE fracture (43,695 hip, 6,001 femoral shaft, 2,481 tibia-fibula). The unadjusted IR of LE fractures were 1.32/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 1.27-1.38) for tibia-fibula, 3.20/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 3.12-3.29) for femoral shaft, and 23.32/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 23.11-23.54) for hip. As compared with hip fracture residents, non-hip LE fracture residents were more likely to be immobile (58.1% vs 18.4%), dependent in all ADLs (31.6% vs 10.8%), transferred mechanically (20.5% vs 4.4%), overweight (mean BMI 26.6 kg/m2vs. 24.0), and have diabetes (34.8% vs 25.7%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings that non-hip LE fractures often occur in severely functionally impaired residents suggests these fractures may have a different mechanism of injury than hip fractures. The resident differences in our study highlight the need for distinct prevention strategies for hip and non-hip LE fractures.

Keywords: nursing home, tibia-fibula fracture, femoral shaft fracture, hip fracture, long-term care

INTRODUCTION

Lower extremity (LE) fractures are frequent and morbid events for nursing home (NH) residents. The rate of hip fractures in NH residents is approximately two-fold greater than in community dwellers.1 Fracture incidence is associated with an increased mortality that remains elevated for years.2,3 Following a fracture, NH residents utilize health care more frequently, including outpatient and emergency department visits.4 Identifying risk factors for LE fractures can prevent injury and illness in this vulnerable population.3,5

Prior studies have investigated the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of hip (proximal femur) fractures in NH residents. Much less is known about non-hip LE fractures, including femoral shaft and non-ankle tibia-fibula fractures. A prior single-center study suggested that these fractures occur in approximately 1% of long-stay NH residents.6 Residents experiencing a non-hip LE fracture share some characteristics with residents experiencing a hip fracture, like older age.7 However, case reports and small cohort studies with highly selected samples suggest non-hip LE fractures may occur in the most incapacitated and immobile patients, whereas hip fractures typically occur during a fall in ambulatory residents.6,8–10

Our objective was to estimate the nationwide incidence of hip and non-hip LE fractures in U.S. NH residents, and to examine differences in resident characteristics between those with hip and non-hip LE fractures.

METHODS

Data source:

Data were ascertained from the Minimum Data Set (MDS, version 2.0) files linked to Medicare fee-for-service (Parts A, B, and D) claims from 1/1/2008 to 12/31/2011. The MDS is a comprehensive resident assessment instrument containing over 400 items. It is federally mandated to be completed on all U.S. NH residents at the time of admission and quarterly thereafter.11 The Residential History File12 was used to provide a daily account of the location where the resident received health services until death. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hebrew SeniorLife.

Study population:

Because LE fractures may be treated in either an inpatient or outpatient setting,13,14 the source population included all long stay NH residents enrolled in both Medicare Parts A (inpatient) and B (outpatient) between 1/1/2008 and 12/31/2009 with follow-up through 12/31/2011. We defined long-stay as older adults who had spent ≥ 100 days in the same NH with no more than 10 consecutive days outside the facility. Residents must have had continual Medicare coverage during the 6-months before their long-stay qualification date.

To describe resident characteristics among subjects with a LE fracture, residents without a Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment within 100 days of long-stay qualification were excluded. Residents <65 years of age and those enrolled in hospice were also excluded. The final sample included 1,257,279 residents. Residents were followed from 1/1/2008 or the date of long-stay qualification until the first event of fracture, death, 60 days following discharge from the NH, or end of the 2-year period.

LE Fracture:

Hip and non-hip LE fractures were determined according to Medicare Parts A and B (outpatient) claims using ICD-9 and CPT codes (Supplementary Appendix S1) based on validated definitions.15,16 If a subject had codes indicating more than one fracture on the same day, inpatient (Part A) procedural codes were prioritized to categorize fracture location. When the fracture site was unclear (e.g., multiple procedural codes), residents were excluded from the analysis (n=461). Pathologic fractures (<1% of all LE fractures) were not included because they may be associated with malignancy rather than osteoporosis. Ankle fractures occur more commonly,17 but they are less often associated with low bone mineral density compared with other non-hip LE fractures.18 Because the risk factors and mechanisms of injury for ankle fractures likely differ from other non-hip LE fractures, we excluded ankle fractures from this report. Residents with multiple fractures during follow-up were categorized according to the first fracture site.

Resident Characteristics:

We obtained age and sex from the Medicare Enrollment file. Resident characteristics were obtained from the closest MDS assessment preceding long-stay qualification. Functional status was described according to dependence in locomotive and non-locomotive Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). Cognitive status was ascertained using the validated Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS).19 Residents’ severity of illness was described according to the MDS-Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs (CHESS) score.20 We also measured individual comorbidities using the MDS. Other characteristics included requirement for mechanical lift, receipt of tube feeding, wandering, pressure ulcers, bladder incontinence, history of falls, and body mass index (BMI). Prescription drug use in the past year (any versus none) was obtained from Medicare Part D claims, including bisphosphonates, inhaled corticosteroids, oral glucocorticoids, thiazide diuretics, and antiepileptics. Nearly 90% of long-stay NH residents rely on Medicare Part D for prescription drug coverage.21,22 Non-vertebral fractures (excluding vertebrate, face, skull, fingers, toes, and ribs) in the past year were obtained from Medicare Parts A and B claims.

Statistical Analysis:

Poisson regression was performed to estimate the incidence rates of fracture and 95% CI (overall and stratified by age and sex). The calculation was performed separately for proximal femur, femoral shaft and tibia-fibular fracture. To compare the resident characteristics across the three groups, we used the Chi squared test and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). We used SAS v.9.4 for all analyses

RESULTS

During 42,800 person-years follow-up, 52,177 NH residents (4.5%) sustained a LE fracture (43,695 hip, 6,001 femoral shaft, and 2,481 tibia-fibula). Overall, 78.1% of residents were female with a mean (SD) age of 84.7 years (±7.6). 24.8% residents were totally dependent in locomotion.

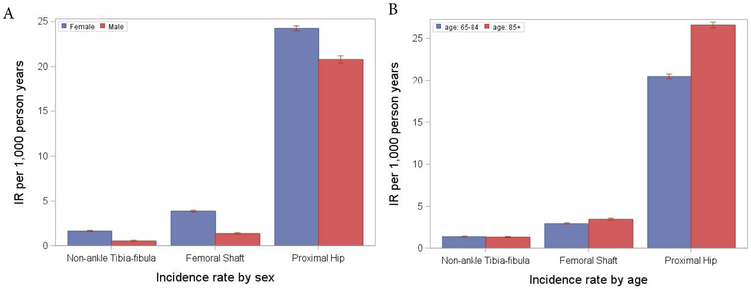

The unadjusted IR of hip fracture was 23.32/1,000 person years (95% CI, 23.11–23.54). The IR of non-hip LE fractures was lower: 1.32/1,000 person years (95% CI, 1.27–1.38) for tibia-fibula and 3.20/1,000 person years (95% CI, 3.12–3.29) for femoral shaft. For hip and femoral shaft fractures the IR increased with age. The incidence of tibia-fibula fracture decreased with age although confidence intervals were overlapping: 1.35/ 1000 person years (95% CI, 1.28–1.42) in residents <85 years and 1.30/1000 person years (95% CI, 1.23–1.38) in residents ≥85 years. The IRs stratified according to age and sex are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Incidence rates of Tibia-Fibula, Femoral Shaft, and Proximal Hip Fracture by A) Sex, and B) Age

Residents with non-hip LE fractures were more likely to be female (89.4% tibia-fibula, 88.0% femoral shaft, vs. 76.0% hip), non-white minority, and receive tube feeds (5.3% tibia-fibula, 4.7% femoral shaft, vs. 2.3% hip; Table 1). Non-hip LE versus hip fracture residents were more likely to be immobile (60.8% tibia-fibula, 57.0% femoral shaft, vs. 18.4% hip), dependent in ADLs, and mechanically lifted (21.2% tibia-fibula, 20.3% femoral shaft, vs. 4.4% hip). Residents with non-hip LE fractures had a higher BMI (mean 26.6 kg/m2 tibia-fibula and femoral shaft vs. 24.0 kg/m2hip) and were more likely to have diabetes. Non-hip LE fracture residents were more likely to have a history of non-vertebral fracture (16.4% tibia-fibula, 16.9% femoral shaft, vs. 12.1% hip) and severe cognitive impairment as compared with hip fracture residents. Residents with non-hip LE fractures were also less likely to wander or have a history of falls (41.3% tibia-fibula, 42.4% femoral shaft, vs. 55.3% hip) as compared to residents with hip fracture. Residents with non-hip LE fractures were more likely to be prescribed an antiepileptic. Use of other classes of medications was similar between fracture types.

Table 1.

Resident Characteristics by Lower Extremity Fracture Site

| Resident Characteristicsa | Tibia-Fibula n=2,481 |

Femoral Shaft n=6,001 |

Proximal Femur (i.e., hip fracture) n=43,695 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 83.4 (±8.6) | 84.3 (±8.0) | 84.8 (±7.4) |

| Female | 89.4% | 88.8% | 76.0% |

| Race | |||

| White | 87.1% | 85.5% | 91.7% |

| Black | 10.4% | 11.2% | 5.1% |

| Hispanic | 1.1% | 1.6% | 1.4% |

| Other | 1.1% | 1.5% | 1.6% |

| Total Dependence Locomotion** | 60.8% | 57.0% | 18.4% |

| Total Dependence Bed Mobility | 18.1% | 14.4% | 3.0% |

| Total Dependence Walk in Corridor | 62.7% | 58.7% | 21.3% |

| Total Dependence Eating | 11.3% | 9.7% | 2.9% |

| Total Dependence Dressing | 23.4% | 19.5% | 6.4% |

| Total Dependence Toileting | 33.5% | 31.0% | 9.4% |

| Total Dependence Hygiene | 27.0% | 24.2% | 8.9% |

| Total Dependence Transfer | 29.7% | 25.6% | 4.7% |

| Bedfast | 3.7% | 3.6% | 0.8% |

| Lifted Mechanically | 21.2% | 20.3% | 4.4% |

| Cognitive Performance Scale | |||

| Intact | 18.8% | 17.0% | 12.6% |

| Borderline Intact | 13.8% | 13.0% | 11.2% |

| Mild Impairment | 16.9% | 18.0% | 19.5% |

| Moderate Impairment*** | 37.1% | 40.6% | 48.7% |

| Severe Impairment**** | 13.4% | 11.3% | 8.0% |

| Dementia | 47.1% | 47.2% | 57.9% |

| Comorbidities CHESS Score | |||

| 0 | 65.7% | 63.1% | 67.2% |

| 1-2 | 32.8% | 35.5% | 31.1% |

| 3-4 | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.7% |

| Diabetes | 36.5% | 34.1% | 25.7% |

| Arthritis | 38.2% | 43.4% | 31.7% |

| Arteriosclerotic Heart Disease* | 14.6% | 14.1% | 12.9% |

| Osteoporosis | 29.2% | 28.7% | 23.4% |

| Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke) | 21.7% | 20.0% | 14.9% |

| Hemiplegia/Hemiparesis | 11.5% | 9.5% | 4.5% |

| Parkinson’s Disease* | 4.8% | 5.5% | 6.2% |

| Presence of Feeding Tube | 5.3% | 4.7% | 2.3% |

| Lost Weighte* | 7.6% | 9.0% | 8.8% |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2, mean (SD)f | 26.6 (±6.8) | 26.6 (±6.7) | 24.0 (±5.0) |

| Non vertebral fracture in the past year | 16.4% | 16.9% | 12.1% |

| History of Falls | 41.3% | 42.4% | 55.3% |

| Wandering | 3.5% | 5.2% | 14.6% |

| Bladder Continence | |||

| Usually Continent | 43.7% | 45.4% | 66.1% |

| Occasionally Incontinent | 17.9% | 19.0% | 18.8% |

| Frequently Incontinent | 38.4% | 35.6% | 15.1% |

| Pressure Ulcer | 9.6% | 10.7% | 5.2% |

| Inhaled Corticoidsteroid Use | 11.3% | 9.5% | 9.3% |

| Oral Glucocorticoid Use | 18.5% | 17.8% | 16.1% |

| Bisphosphonate Use | 18.7% | 16.0% | 14.4% |

| Thiazide Diuretics Use | 12.0% | 14.2% | 14.5% |

| Antiepileptic Use | 26.6% | 23.8% | 17.6% |

All p-values <0.0001 except those indicated by

two or more people required to provide locomotion on unit

including Moderate Impairment and Moderately Severe Impairment

including Severe Impairment and Very Severe Impairment

5% or more in last 30 days; or 10% or more in last 180 days

Standard Deviation

DISCUSSION

In this nationally-representative cohort of NH residents, we found that non-hip LE fractures occur approximately one tenth as often as hip fractures. We identified key differences in resident characteristics between those experiencing a hip and non-hip LE fracture: residents with non-hip LE fractures were more immobile, dependent in ADLs, and had a higher BMI than residents with hip fractures.

In cohorts with wide-ranging sample sizes (N=55–9,000), LE fractures have been associated with female sex and with advanced age. 2,6–8,23 In our study, women also had a higher incidence of LE fractures of all types as compared with men, particularly non-hip LE fractures. It is less clear whether non-hip LE fractures are associated with age given the inverse association we observed with tibia-fibular and femoral shaft fractures, with overlapping confidence intervals.

We found that residents experiencing a non-hip LE fracture are often severely functionally impaired; this confirmed findings from prior case-series which examined a limited number of residents with non-hip LE fractures (N=6–22).6,9,23,24 Furthermore, our study showed that non-hip LE fracture residents were typically overweight, with a mean BMI of 26.6 kg/m2. This is consistent with previous studies involving community-dwelling older adults where more than half of those with tibia-fibula fractures had a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2.10 The literature associating cognition25,26 and previous fractures2,27 to non-hip LE fractures has been inconsistent. We found residents with non-hip LE fractures were somewhat more likely to exhibit severe cognitive impairment and non-vertebral fractures as compared with hip fracture residents. Wandering was far less common in residents with non-hip LE fractures, a behavior that increases a resident’s risk of falling.8 The marked differences in functional characteristics between hip and non-hip LE fractures implies a different mechanism of injury and suggests that non-hip LE fractures may occur outside of falls.

We found little difference in medication use between residents experiencing a hip and non-hip LE fracture. Antiepileptic use was somewhat more common in residents with a non-hip LE fracture as compared with hip fracture. Steroid and bisphosphonate use was slightly more common and thiazide use less common in residents with a femoral shaft fracture as compared with other lower extremity fracture types. Thiazide diuretics have been associated with a decreased risk of lower extremity fracture in immobile men with spinal cord injury28 and a decreased risk of hip fracture in community-dwellers.29 Given the modest difference we found in medication use among the LE fracture types, it is unclear whether medications influence risk of non-hip LE fractures in NH residents.

The circumstances of non-hip LE fracture in NH residents are not widely known. In younger community dwellers, non-hip LE fractures generally occur due to trauma from falls or motor vehicle accidents.30 Small case reports and cohort studies suggest that approximately 1 out of 4 occurrences of non-hip LE fractures in long-term care happen with minimal or no trauma in the absence of a fall.2,6,23–25,31,32 These fractures are often termed spontaneous or insufficiency fractures23 that present insidiously with pain and deformity at rest or upon positioning or transferring.23,25,31 Case-series including few NHs conclude that unsafe practices of transferring could be the culprit for these spontaneous fractures. 2,6,32 Our study supports these conclusions given the relatively high proportion of non-hip LE fracture residents who were immobile and unlikely to fall.

The incidence of non-hip LE fractures is small compared to traditional hip fractures in NHs. However, a large proportion of all non-hip LE fractures occur in NH residents. In a study of 43 geriatric distal femur fractures, 1/3 of patients presenting with non-hip LE fractures were NH residents, and these NH residents had the highest mortality.5 If non-hip LE fractures are in fact often occurring in the setting of transfers, staff practices and equipment may be more modifiable than traditional falls risk factors in NH residents.

This study has limitations. First, misclassification of fractures is possible. However, the positive predictive value of Medicare claims to identify fracture is good (79% tibia-fibula, 87% femoral shaft, 98% hip). 33 Multiple procedural codes make the fracture site uncertain, therefore, these fractures were excluded to reduce misclassification. Second, information on long-term exposure to bisphosphonates prior to NH admission was unavailable. Prolonged bisphosphonate use may increase risk of atypical femur fractures, a specific femoral shaft fracture.34 Finally, we lacked detailed information regarding fracture circumstance. The high proportion of immobile residents that experienced a non-hip LE fracture suggests that these fractures often occur outside the setting of a fall. A study of non-hip LE fracture detailing circumstance, including the type of equipment involved and number of staff assisting, would be useful to clarify the mechanisms of injury.

CONCLUSION

Fracture prevention strategies are important to avoid the burden of mortality and decreased quality of life for NH residents.35 The observed resident differences suggest non-hip LE fractures may have a different mechanism of injury than hip fractures and may occur without a fall. Distinct prevention strategies should be implemented in immobile residents at high risk, such as attention to lifting and transferring strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1. Diagnosis and Procedure Codes to Define Fracture Sites

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

• Sponsor’s Role: The funding agency played no role in the analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute on Aging (NIA), #1R01AG045441.

Footnotes

• Conflicts of Interest: None to declare

REFERENCES

- 1.Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, et al. Comparative trends in incident fracture rates for all long-term care and community-dwelling seniors in Ontario, Canada, 2002–2012. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:887–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hommel E, Ghazi A, White H. Minimal trauma fractures: lifting the specter of misconduct by identifying risk factors and planning for prevention. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam K, Leung MF, Kwan CW, Kwan J. Severe Spastic Contractures and Diabetes Mellitus Independently Predict Subsequent Minimal Trauma Fractures Among Long-Term Care Residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:1025–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman S, Chandler JM, Hawkes W, et al. Effect of fracture on the health care use of nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kammerlander C, Riedmuller P, Gosch M, et al. Functional outcome and mortality in geriatric distal femoral fractures. Injury 2012;43:1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane RS, Burns EA, Goodwin JS. Minimal Trauma Fractures in Older Nursing-Home Residents - the Interaction of Functional Status, Trauma, and Site of Fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1995;43:156–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieves JW, Bilezikian JP, Lane JM, et al. Fragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristics. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry SD, Zullo AR, Lee Y, et al. Fracture Risk Assessment in Long-term Care (FRAiL): Development and Validation of a Prediction Model. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:763–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso-Bartolome P, Martinez-Taboada VM, Blanco R, Rodriguez-Valverde V. Insufficiency fractures of the tibia and fibula. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999;28:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelsey JL, Keegan TH, Prill MM, Quesenberry CP Jr., Sidney S Risk factors for fracture of the shafts of the tibia and fibula in older individuals. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JN, Hawes C, Fries BE, et al. Designing the national resident assessment instrument for nursing homes. Gerontologist 1990;30:293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, Miller SC, Mor V. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories(*). Health Serv Res 2011;46:120–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry SD, Zullo AR, McConeghy K, Lee Y, Daiello L, Kiel DP. Defining hip fracture with claims data: outpatient and provider claims matter. Osteoporos Int 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry SD, Zullo AR, McConeghy K, Lee Y, Daiello L, Kiel DP. Administrative health data: guilty until proven innocent. Response to comments by Levy and Sobolev. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:255–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron JA, Karagas M, Barrett J, et al. Basic epidemiology of fractures of the upper and lower limb among Americans over 65 years of age. Epidemiology 1996;7:612–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry SD, Zullo AR, McConeghy K, Lee Y, Daiello L, Kiel DP. Defining hip fracture with claims data: outpatient and provider claims matter. Osteoporos Int 2017;28:2233–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baron JA, Lu-Yao G, Barrett J, McLerran D, Fisher ES. Internal validation of Medicare claims data. Epidemiology 1994;5:541–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeley DG, Browner WS, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Scott JC, Cummings SR. Which fractures are associated with low appendicular bone mass in elderly women? The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, Koch GG, Mitchell CM, Phillips CD. Validation of the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale: agreement with the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50:M128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirdes JP, Frijters DH, Teare GF. The MDS-CHESS scale: a new measure to predict mortality in institutionalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briesacher BA, Soumerai SB, Field TS, Fouayzi H, Gurwitz JH. Nursing home residents and enrollment in Medicare Part D. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1902–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General. Availability of Medicare Part D drugs to dual-eligible nursing home residents 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Hunyadi C, Heitz D, Kaltenbach G, et al. Spontaneous insufficiency fractures of long bones: a prospective epidemiological survey in nursing home subjects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2000;31:207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane RS, Goodwin JS. Spontaneous fractures of the long bones in nursing home patients. Am J Med 1991;90:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong TC, Wu WC, Cheng HS, Cheng YC, Yam SK. Spontaneous fractures in nursing home residents. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:427–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Magaziner JS, Passarella MA, Mehta S, Werner RM. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manevich D, Brill S, Hershkovitz A. Spontaneous insufficiency fractures of long bones in institutionalized elderly patients. Aging Clin Exp Res 2010;22:95–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carbone LD, Chin AS, Lee TA, et al. Thiazide use is associated with reduced risk for incident lower extremity fractures in men with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1015–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao X, Xu Y, Wu Q. Thiazide diuretic usage and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:1515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss RJ, Montgomery SM, Al Dabbagh Z, Jansson KA. National data of 6409 Swedish inpatients with femoral shaft fractures: Stable incidence between 1998 and 2004. Injury-International Journal of the Care of the Injured 2009;40:304–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salminen S, Pihlajamaki H, Avikainen V, Kyro A, Bostman O. Specific features associated with femoral shaft fractures caused by low-energy trauma. J Trauma 1997;43:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takamoto S, Saeki S, Yabumoto Y, et al. Spontaneous fractures of long bones associated with joint contractures in bedridden elderly inpatients: clinical features and outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:703–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA 2011;305:783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarride JE, Burke N, Leslie WD, et al. Loss of health related quality of life following low-trauma fractures in the elderly. Bmc Geriatrics 2016;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1. Diagnosis and Procedure Codes to Define Fracture Sites