Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Elder mistreatment is common and has serious social and medical consequences for victims. Though programs to combat this mistreatment have been developed and implemented for more than three decades, previous systematic literature reviews have found very few successful ones.

OBJECTIVE:

To conduct a more comprehensive examination of programs to improve elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention, including those that had not undergone evaluation.

DESIGN:

Systematic review

SETTING:

Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO (EBSCO), AgeLine, CINAHL

MEASUREMENTS:

We abstracted key information about each program and categorized programs into 14 types and 9 sub-types. For programs that reported an impact evaluation, we systematically assessed the study quality. We also systematically examined the potential for programs to be successfully implemented in environments with limited resources available.

RESULTS:

We found 116 articles describing 115 elder mistreatment programs. 43% focused on improving prevention, 50% on identification, and 95% on intervention, with 66% having multiple foci. The most common types of program were: educational (53%), multi-disciplinary team (21%), psycho-education / therapy / counseling (15%), and legal services / support (8%). 13% of programs integrated an acute-care hospital. 43% had high potential to work in low-resource environments. 57% reported an attempt to evaluate program impact, but only 2% used a high-quality study design.

CONCLUSION:

Many programs to combat elder mistreatment have been developed and implemented, with the majority focusing on education and multi-disciplinary team development. Though more than half reported evaluation of program impact, very few used high-quality study design. Many have the potential to work in low-resource environments. Acute care hospitals were infrequently integrated into programs.

Keywords: elder abuse, systematic review, intervention

INTRODUCTION

Elder mistreatment is defined as physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, neglect, abandonment, or financial exploitation of an older person in any setting (e.g. home, community, or facility) in a relationship where there is an expectation of trust and/or when an older person is targeted based on age or disability.1 This mistreatment occurs commonly, with conservatively 5–10% of community-dwelling adults aged ≥60 affected each year1–6 and many victims suffering from multiple types concurrently. Elder mistreatment can have a profound social and health impact on victims, significantly increasing their risk for depression,7 exacerbations of chronic illness, emergency department usage,8,9 hospitalization,10 nursing home placement11,12and death.6,13,14 The societal cost, though difficult to estimate, is likely many billions of dollars annually in direct medical costs,1,15 financial loss through exploitation, and services provided for victims. Though common, serious, and costly, elder mistreatment is rarely identified, with as few as 1 in 24 cases reported to the authorities.3 Therefore, identification, intervention, and, ultimately, prevention of elder mistreatment are important public health priorities.1,6,16

Programs to combat elder mistreatment have been developed and implemented for more than three decades, and many vulnerable older adults, as well as families and professionals who serve them, have benefitted. Despite this, previous systematic literature reviews17–27 examining programs have found very few that systematically analyzed outcomes and even fewer that demonstrated measurable impact. This is partly because of the complexity of designing and evaluating elder mistreatment programs and because the relatively young field includes collaborative teams with various levels of funding and research sophistication. The traditional systematic review approach, which includes and examines only programs that have undergone rigorous evaluation using high-quality study designs, risks missing innovative, promising programs which may have had an important impact on victims and communities.

We sought to conduct a more comprehensive examination of published programs, including those that had not undergone evaluation. We focused on the potential role of acute care hospitals in elder mistreatment programs. An emergency department visit or hospitalization may be the only time a homebound victimized older adult leaves their home.16 For these and many other older adults, physical abuse may precipitate an ED visit after injury and neglect may lead to exacerbations of chronic illness or severe infections because of inadequate or inappropriate care. Even financial exploitation may lead to ED presentation when the exploiter directly or the lack of financial resources due to the exploitation prevents an older adult from getting routine medical care including purchasing necessary medications or visiting a provider. Additionally, in most US states, health care providers are mandatory reporters when they suspect elder mistreatment.28

Despite this, limited existing literature suggests that hospital-based health care providers very infrequently detect and report elder mistreatment.16,29 A recent study found that elder abuse was diagnosed in only 0.013% of U.S. ED visits.16,29 Further, only 1.4% of cases reported to Adult Protective Services (APS) come from physicians.30 In a survey of APS workers, of 17 occupational groups, physicians were among the least helpful in reporting abuse.31 This underscores the unique potential for programs to combat elder mistreatment integrating acute care hospitals to be impactful.

Additionally, we hoped to identify programs that would be broadly implementable in settings with fewer resources. We recognized that many existing well-described programs have been implemented at organizations in communities with significant available resources, funding, and support. Many of these programs rely on these resources and would not be possible to implement in low-resource environments. We defined low-resource environments as those lacking: substantial infrastructure for community services, strong collaborative relationships between service-providing agencies, multi-disciplinary elder mistreatment expertise, and financial resources. These low resource environments are often in rural areas or inner cities.

The goal of this research, a preliminary step in the design and development of a new program, was to identify, characterize, and review existing programs dedicated to improving elder mistreatment identification, intervention, and prevention with a focus on programs that integrate acute care hospitals and may be implemented in low-resource environments.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic literature review to identify programs combatting elder mistreatment.

Search Strategy

We collaborated with two research librarians (DD, MD) to develop a comprehensive search strategy to identify peer-reviewed publications about programs combatting elder mistreatment. Searches were run on April 19, 2017 in a broad range of databases:32 Ovid MEDLINE (in-process and other nonindexed citations and Ovid MEDLINE from 1946 to present), Ovid EMBASE (from 1974 to present), Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL], and Cochrane Methodology Register), PsycINFO (EBSCO), and AgeLine (EBSCO). An additional search was run in CINAHL (EBSCO) on May 17, 2017. All searches employed the controlled vocabulary of each database and plain language. Final search results were limited to English language studies. Full search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE is available as online supplementary material (S1). We also evaluated reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles to check for additional studies.

Inclusion Criteria

We included in the review any paper describing a specific program focused on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention. We excluded editorials, topic reviews, and articles giving general recommendations about combatting elder mistreatment. We excluded programs exclusively based in nursing homes or other long-term care settings. We also excluded descriptions and evaluations of screening tools, about which other reviews exist.21,33–38

Review Process

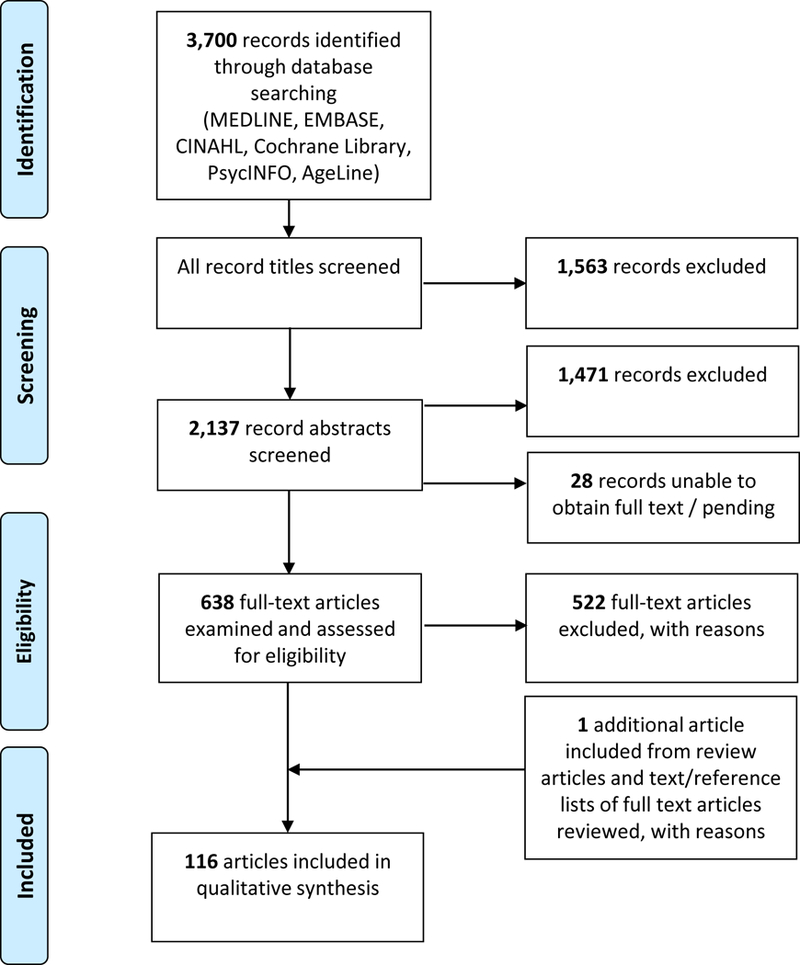

Three study authors (TR, AE, SD) independently screened titles and retrieved and reviewed abstracts and full-text articles for inclusion using a pre-designed protocol incorporating the above-described criteria. Clearly irrelevant records or those not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded based on title or abstract, and full text of each potential article was obtained and evaluated independently by two reviewers. Data was collected and stored in EndNote software (Philadelphia, PA).4 Disagreements about study inclusions were resolved by consensus. A flowchart summarizing results of this article selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Identifying Elder abuse prevention, identification, and intervention strategies: Systematic literature review flow diagram.

Note: Reasons for exclusion during screening and assessment of eligibility included: no description or evaluation of new program or intervention, description or evaluation of screening/identification tool, focus on: resident-to-resident elder mistreatment in nursing homes, reduction of nursing home restraint use, self-neglect, crime victimization.

Data Abstraction and Analysis

For each paper, we abstracted a brief description of the program, its focus(es) (identification, intervention, prevention), type(s) of mistreatment targeted, target population(s), setting(s) where professionals were based, setting(s) where services were provided, and whether an acute care hospital was involved. When we identified multiple articles describing a single program, we examined all articles together rather than each separately. To assist in characterization of programs, we developed seven categories of program type. These categories were generated based on our findings and were developed through consensus after several meetings. Categories included: educational, multi-disciplinary team, psycho-education / therapy / counseling, legal services / support, emergency shelter, home visitation, case management. Notably, we considered forensic centers to be multi-disciplinary teams. Forensic centers are a type of multi-disciplinary team that has a full-time staff and conducts regular face-to-face meetings to review cases as well as joint visits, trainings, and ongoing collaboration.39 For the categories educational and psycho-education / therapy / counseling, we included sub-categories for the target population of the program.

We assessed whether an acute-care hospital was integrated as part of each program. For this, we included programs if an acute-care hospital was a site where program services were provided or where the majority of the professionals providing the services were based. We also considered a program to have integrated an acute-care hospital if transfer of an older adult to an ED/hospital when appropriate was a part of the program. Additionally, for programs that did not integrate an acute-care hospital, we examined whether a hospital served as a potential source of referrals to the program as well as whether any physician or other hospital-based provider was involved in the program. We also assessed the potential of the program working in low-resource environments (very likely, likely, possible, unlikely, very unlikely) through consensus. Lists of characteristics we used to determine whether a program was likely or unlikely to work in a low-resource environment are listed in Table 1. Notably, these lists were intended to be independent of each other. For articles reporting systematic program evaluation, we abstracted study design, number of subjects, and results / evidence of impact. We evaluated study quality by assessing the presence of well-established study design limitations, based in part on the SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting40 and the Journal of the American Medical Association’s Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature’s assessment of articles describing quality improvement.41 Table 2 shows the list of limitations we used. We categorized each study as higher tier, middle tier, or lower tier based on the presence of these limitations through consensus. Our analysis is limited by the fact that elder mistreatment research has not yet established optimal outcomes on which to focus and how to best measure program success. Further, we recognize that analyzing multiple types of interventions together may affect our ability to accurately describe and compare impact. Decisions about strategies for program evaluation are likely driven by program mission and funding source. For example, an educational program for professionals may measure impact on learners rather than older adults. Therefore, for these programs, we have incorporated into the list of limitations distinctions between measurement of increased knowledge vs. self-reported practice change vs. actual practice change.

Table 1:

Characteristics suggesting a program was likely or unlikely to work in a low-resource environment

| Characteristics Suggesting Likely | Characteristics Suggesting Unlikely |

|---|---|

| Intervention may be administered simultaneously to group of caregivers or victims | Requires extensive training and/or oversight for providers |

| Much of intervention may be conducted on telephone | Requires access to trained therapy / clinical providers |

| Training or educational session can be integrated into existing curricula | Involves home visits by multiple health care professionals |

| Requires few training or educational sessions | Requires multiple in-person sessions over extended time |

| New program or protocol is easily integrated into existing processes within institution | Requires full-time staff |

| Training is manualized | Requires non-governmental community-based organization with extensive resources |

| Requires significant ongoing financial support |

Table 2:

Limitations in study design used to assess quality of studies evaluating impact of programs

| Small sample size |

| Non-scientific sample |

| No comparison group |

| Comparison group limited given important differences from study group |

| Use of administrative database not intended for research |

| Only examined short-term outcomes / no long-term follow-up |

| Evidence of change in knowledge only, not practice change |

| Reliance on self-reported outcomes rather than actual practice change |

| No measure of direct impact on victims / older adults |

| Variations in delivery of intervention, including difficulty implementing |

RESULTS

We found 116 articles describing 115 programs in this comprehensive systematic review of peer-reviewed literature. The earliest article describing a program42 was published in 1982. The annual rate of descriptions of new programs in this literature was: 0.04 from 1982–89, 0.26 from 1990–99, 0.39 from 2000–09, and 0.30 from January 1, 2010 – April 19, 2017. Fifteen programs were described in multiple articles (maximum of three articles describing a program) and four articles described multiple programs (as many as seven programs). Thirty-one percent of the 116 articles were published in the Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, which was launched in 1988, 9% in other publications devoted to elder mistreatment, and 60% in journals with a broader focus. Seventy-seven percent of programs were developed in the USA, 8% in the United Kingdom, 7% in Canada, 3% in Australia, and 5% in other countries.

The list of all programs including detailed descriptions of each is available as online supplementary material (S2). Characteristics of these 115 programs are described in Table 3. Notably, 43% of programs focused on improving prevention, 50% on identification, and 95% on intervention, with 66% having multiple focuses. The most common program types were: educational (53%), multi-disciplinary team (MDT) (21%), psycho-education / therapy / counseling (15%), and legal services / support (8%), with 20% of programs having components in multiple categories.

Table 3:

Characteristics of published programs (n=115) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention

| Focus(es) of Program | |

|---|---|

| Prevention | 43% |

| Identification | 50% |

| Intervention | 95% |

| Multiple | 66% |

| Type | |

| Educational | 53% |

| Professionals | 34% |

| Professional Students / Trainees | 11% |

| Public | 10% |

| Older Adults | 9% |

| Family / Informal Caregivers | 4% |

| Multiple | 10% |

| Multi-Disciplinary Team | 21% |

| Psycho-education / Therapy / Counseling | 15% |

| Older Adults | 7% |

| Family / Informal Caregivers | 4% |

| Multiple | 3% |

| Legal Services / Support | 8% |

| Emergency Shelter | 7% |

| Home Visitation | 6% |

| Case Management | 6% |

| Multiple | 20% |

| Mistreatment Type(s) Targeted | |

| Financial Exploitation | 94% |

| Physical Abuse | 83% |

| Neglect | 79% |

| Emotional Abuse | 79% |

| Sexual Abuse | 77% |

| Multiple | 75% |

Target populations, settings, integration of hospitals, likelihood of deployment in low resource environments, and attempts at program evaluation among published programs are shown in Table 4. 57% reported an attempt to evaluate program impact, but only two programs43–47 (2%) were evaluated using a higher tier quality study design and 6 programs48–55 (5%) using a middle tier quality study design. Of those with a high quality study design, both were psychoeducational / therapeutic / counseling, one for older adults and the other for informal/family caregivers. The START program (STrAtegies for RelaTives)43–45 reduced anxiety and depression among caregivers but did not reduce abusive behavior or improve quality of life for older adults. More promisingly, the PROTECT (PRoviding Options To Elder Clients Together)46,47 intervention showed assistance with problem-solving, and, though not statistically significant, decrease in depressive symptoms and improvement in perceived abuse status relative to controls. Among programs evaluated using middle tier quality study design, three were educational,50–52,56 one was a multi-disciplinary team,54,57 one was decision support for clinicians,48 and one combined psychoeducational / therapeutic / counseling and home visitation.53 Most only showed modest short-term impact. An educational program for mental health and home care professionals demonstrated improvement in documentation of abuse and neglect risk assessment, and an educational program for social and health care professionals showed an increased ability to detect financial elder abuse in case scenarios.48 An educational program designed for the public to alter tolerance for and behavioral intentions of elder abuse showed impact in an immediate post-test, but this did not persist at one month.52 In the multi-disciplinary team, cases were more likely to be referred for guardianship and criminal justice, but case resolution times were not shorter.49,54 For the combined psychoeducational / therapeutic / counseling and home visitation program, several types of elder abuse (emotional neglect, care neglect, financial neglect, curtailment of personal autonomy, psychological abuse, and financial abuse – but not physical abuse) were reduced 30 days post-intervention vs. controls using self-report to measure.53

Table 4:

Target populations, settings, integration of hospitals, likelihood of deployment in low resource environments, and attempts at program evaluation among published programs (n=115) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention

| Target Population(s) | |

|---|---|

| Older Adult / Victim | 57% |

| Health Care Provider | 22% |

| Community Service Provider | 19% |

| Caregiver / Potential Perpetrator | 7% |

| Home Health Aide | 3% |

| Multiple | 16% |

| Setting(s) Where Professionals Based | |

| Community-Based Organizations | 49% |

| Hospital / Academic Medical Center / Outpatient Medical Clinic | 16% |

| Academic Institution / University | 12% |

| Law Enforcement / Legal / District Attorney’s Office / Court | 10% |

| APS | 7% |

| Other Medical (Emergency Medical Services, Home Care) | 3% |

| Nursing Home | 3% |

| Other* | 6% |

| Multiple | 27% |

| Not reported | 6% |

| Setting(s) Where Services Provided | |

| Community / Community Based-Organization | 66% |

| Victim’s Home | 17% |

| Hospital / Academic Medical Center / Outpatient Medical Clinic | 12% |

| Academic Institution / University | 6% |

| Law Enforcement / Legal / District Attorney’s Office / Court | 6% |

| APS | 3% |

| Via Telephone | 3% |

| Other** | 13% |

| Multiple | 25% |

| Not reported | 11% |

| Hospital Integrated into Program | 13% |

| Hospital Not Integrated into Program, but: | |

| Hospital Serves as Referral Site | 5% |

| Hospital-Based Provider Involved | 17% |

| Likelihood of Deployment in Low Resource Environments | |

| Very Likely | 4% |

| Likely | 18% |

| Possible | 21% |

| Unlikely | 29% |

| Very Unlikely | 28% |

| Reported Attempt at Program Evaluation | |

| Any | 58% |

| Evaluation with Higher Quality Tier Study Design | 2% |

| Evaluation with Middle Quality Tier Study Design | 5% |

| Evaluation with Lower Quality Tier Study Design | 51% |

Other Settings Where Professionals Based included: Shelters, Banks, Churches, Department for the Aging

Other Settings Where Services Provided included: Shelters, Banks, Online, Emergency Medical Services, Home Health Care Agencies, Churches, Continuing Education Events – no further information

Thirteen percent of programs42,56,58–71 integrated an acute-care hospital in the intervention. The 15 programs which integrated acute care hospitals are listed and described in more detail in online supplementary material (S3). An additional 5%, though they did not integrate an acute-care hospital, used the hospital as a potential source of referrals to the program, and 17% had a physician or other hospital-based provider involved in the program. Thus, a total of 35% of programs had some relationship to an acute care hospital. 22% of all programs were likely or very likely deployable in low-resource environments with an additional 21% possible.

Programs that integrated acute care hospitals differed from those that did not in important ways. Programs integrating hospitals less often focused on prevention (13% vs. 43% of all programs). Also, a higher percentage (40% vs. 28% of all programs) were very unlikely deployable in low-resource environments, highlighting that many of these programs were resource-intensive.

DISCUSSION

This review represents, to our knowledge, the first report attempting to comprehensively describe published elder abuse programs without excluding those that had not undergone rigorous evaluation. As such, it offers an opportunity to broadly examine strategies used to combat this common, serious, and under-appreciated phenomenon. More programs focused on intervening on existing mistreatment rather than prevention or identification. Financial exploitation and physical abuse were the most common types of abuse targeted, perhaps because they were perceived to be the most serious or common. Also, both lent themselves to collaborative solutions involving social services, law enforcement, health care, and financial services. Notably, 75% of programs targeted multiple types of mistreatment rather than focusing on a single type. Though likely to be relevant to a broader range of victims, we believe, based on our previous program-related experience, that differences in victims, perpetrators, and surrounding circumstances between types of mistreatment may have reduced programs’ ability to demonstrate a large impact.

Programs included approaches in seven categories, suggesting that a wide variety of strategies have been employed. Twenty percent of programs included multiple categories of strategy. This suggests that the field is undertaking more ambitious, integrated interventions. Notably, however, 74% of programs were either educational or multi-disciplinary teams. Educational programs (53%) may have been most common because they were easier to implement or integrate into existing programs and less resource-intensive than other approaches. Programs most commonly targeted professionals and professional students / trainees, and their utility was underscored by participant reports that the programs were helpful and necessary. Unfortunately, most of these educational programs involved one or a small number of training sessions, and their long-term impact or their effect on actual elder mistreatment prevention, identification, and intervention was not evaluated. Multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) were also common, emphasizing the recognized value of inter-disciplinary collaboration in combating elder mistreatment. Though MDTs, particularly large teams with a devoted coordinator, are typically more resource-intensive than educational interventions, these multi-disciplinary programs have been publicized and disseminated.72 Notably, the structure, participants, and focus varied widely between MDT programs we examined, suggesting the importance of improving understanding of the types that exist currently, identifying optimal approaches through comparative research, and disseminating tools and best practices. Initial stages of this work are already underway with an ongoing study surveying existing MDTs73 and development of a toolkit by the US Department of Justice.74

Adult Protective Services (APS) played a critical role in many of the programs we described. APS is a social services program provided by state and local government nationwide serving older adults and adults with disabilities. In all states, APS is charged with receiving and responding to reports of maltreatment and working closely with clients and a wide variety of allied professionals to maximize clients’ safety and independence.75 APS caseworkers were the focus of some educational interventions and were also the professionals providing a variety of interventions. Particularly, APS served as a member of the many of the MDTs.

More than half of the programs report at least some attempt at evaluation, suggesting that the field recognizes the importance of measuring impact. Unfortunately, only two programs used a higher tier quality study design, and six used a middle tier quality. With few exceptions, these programs, which were rigorously evaluated, generally only showed a modest measurable impact. This finding confirms other systematic reviews,19,26 which have concluded that no programs with high-quality study designs have shown significant measurable impact. It emphasizes the challenges in designing and conducting research to evaluate elder mistreatment programs. This highlights opportunities for improvement of techniques. Additionally, conducting high-quality evaluation research can be expensive, and additional funding is needed.

A surprising finding is that the number of new programs described in the literature is stable, rather than increasing. An increase might be expected given that recognition of the importance of the elder mistreatment has grown. This suggests the possibility that development of new programs may not be increasing in parallel to increased recognition of the phenomenon. Alternatively, program developers may be choosing methods for dissemination other than academic literature, such as websites or blog posts. Notably, a higher percentage of programs described recently in the literature include evaluation, particularly higher or middle quality study designs. This suggests that the absence of increase in published programs may also reflect tightening of publication standards for manuscripts describing innovative programs.

Encouragingly, a larger percentage (22%) of programs would very likely or likely be deployable in low resource environments. Ninety-two percent of these programs were educational. Though a critical initial step to combat elder mistreatment, many of these programs showed only modest short-term impact on knowledge and attitudes of professionals. None demonstrated impact on safety of older adults. Many of the most promising collaborative strategies (including home visitation, social services / legal services collaborations, emergency shelters, and multi-disciplinary teams) as well as programs that integrated multiple strategies have the potential for greater impact but are less likely to be implemented in low resource environments. As a result, appropriating these strategies to design interventions to implement in low-resource environments may require modifying or simplifying as well as adapting individual components of programs reported on here. This adaptation may be based in part on the resources available in each community.

Only 13% of programs integrated an acute-care hospital and 7% provided services within the hospital itself. This represents an important potential opportunity for focus for future programs. Hospitals are highly resourced, multi-disciplinary, open 24 hours a day, and have established strategies for quality improvement program evaluation as well as professional education. Additionally, though hospitalization may be a critical opportunity to identify elder mistreatment and intervene, existing literature suggests that providers currently infrequently detect it. This further underscores the potential for an innovative program integrating an acute care hospital to have a large impact. Among the programs integrating an acute-care hospital, a broad range of strategies were employed, including educational interventions (60%), multi-disciplinary teams (20%), and protocols (13%). Among these programs, only educational interventions (33% of all programs) had high likelihood of being implemented in low-resource environments. This suggests that innovative programming approaches are still needed for impactful programs integrating acute-care hospitals and deployable in low resource environments. Re-focusing efforts on developing programs for this setting may be very helpful.

Notably, an additional 22% of programs either used the hospital as a potential source of referrals to the program or had a physician or other hospital-based provider involved in the program. These programs may already have an established foundation that may make them ideal targets for expansion to fully integrate an acute care hospital. Additionally, opportunities to more closely connect APS, given their investigative responsibilities, with acute care hospitals may be particularly fruitful in enhancing the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the entire system of prevention, identification, and intervention.

Our finding among all programs that resource-intensive strategies often had higher impact highlights the importance of future research examining the potential of programs to reduce health care and other costs associated with elder mistreatment. Though these studies have not yet been conducted, they are critical to developing a business case for communities and local governments as well as insurers, accountable care organizations, and hospitals to justify implementation of resource-intensive programs in low-resource environments.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Though we used an established, systematic approach, our search strategy may have missed key articles and not included relevant programs. Our search did not include the social services and legal literature, an important limitation given the multi-disciplinary nature of elder mistreatment response. We chose this approach because of our goal of identifying programs that integrated acute care hospitals and certainly didn’t intend to de-value the critical input from other disciplines. Notably, however, of the 116 articles we included in this review, 75 were published in journals that would be categorized as social science. We also did not include non-English studies, grey literature, abstracts, or theses. Programs that we included may have updates or additional information about which we were unaware. Despite this, we believe that this comprehensive review offers valuable, important new insights about the state of elder mistreatment program development and evaluation within the field.

CONCLUSION

Many programs to combat elder mistreatment have been developed and implemented using a wide variety of strategies. Most are educational programs or multi-disciplinary teams. Many have the potential to work in low-resource environments. Acute care hospitals are infrequently integrated into programs, suggesting a potential missed opportunity. These findings suggest existing challenges and future directions for program development and evaluation research.

Supplementary Material

Full search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE to find programs developed to combat Elder Mistreatment

Comprehensive data abstraction list of published programs (n=115) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention

Details of published programs (n=15) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention that integrate acute care hospitals

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the generous support and participation of the John A. Hartford Foundation in the development of the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment Project. This work also been generously funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Tony Rosen’s participation has been supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant (R03 AG048109) and a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. He is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

Funding sources: Our review was conducted by the members of the National Collaboration to Address Elder Mistreatment Project Team, a group from several institutions funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation and including members of the Hartford Foundation leadership team. This work, which is a preliminary step in the design and development of an acute-care hospital-based intervention intended for low-resource environments to improve identification, intervention, and prevention of elder mistreatment, has also been funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Sponsor’s Role: For this systematic review, the sponsor (John A. Hartford Foundation) had several employees (Rani Snyder, Amy Berman, and Terry Fulmer) contribute as authors to the design, methods, data collection, analysis and preparation of paper. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation had no role.

This research was funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation through the creation of the National Collaboration to Address Elder Mistreatment. Principal Investigators on this project from different sites include: Alice Bonner, CBD, MSL.

RS, Amy Berman, and TF all are employees of the John A. Hartford Foundation, a foundation dedicated to improving the care of older adults through research focused on age friendly health systems, end-of-life care & family caregiving, which provided support for this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: TR’s participation has been supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant (R03 AG048109) and a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. He is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Elder Abuse. The Elder Justice Roadmap: A Stakeholder Initiative to Respond to an Emerging Health, Justice, Financial, and Social Crisis. [Online] https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download. Accessed August 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys 2012. [On-line]. https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 4.Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health 2010;100:292–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet 2004;364:1263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachs MS, Pillemer KA. Elder abuse. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyer CB, Pavlik VN, Murphy KP, Hyman DJ. The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between elder abuse and use of ED: findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, et al. ED use by older victims of family violence. Ann Emerg Med 1997;30:448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA. Adult protective service use and nursing home placement. Gerontologist 2002;42:734–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology 2013;59:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA 1998;280:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong XQ, Simon MA, Beck TT, et al. Elder abuse and mortality: the role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology 2011;57:549–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mouton CP, Rodabough RJ, Rovi SL, et al. Prevalence and 3-year incidence of abuse among postmenopausal women. Am J Public Health 2004;94:605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen T, Hargarten S, Flomenbaum NE, Platts-Mills TF. Identifying elder abuse in the emergency department: toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:378–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alt KL, Nguyen AL, Meurer LN. The Effectiveness of Educational Programs to Improve Recognition and Reporting of Elder Abuse and Neglect: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Elder abuse Negl 2011;23:213–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayalon L, Lev S, Green O, Nevo U. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to prevent or stop elder maltreatment. Age Ageing 2016;45:216–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker PR, Francis DP, Hairi NN, Othman S, Choo WY. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016:CD010321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Day A, Boni N, Evert H, Knight T. An assessment of interventions that target risk factors for elder abuse. Health & Social Care in the Community 2016:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong XQ. Elder Abuse: Systematic Review and Implications for Practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1214–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fearing GM, Sheppard CLM, McDonald LP, Beaulieu MP, Hitzig SLP. A systematic review on community-based interventions for elder abuse and neglect. J Elder Abuse Negl 2017:24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirst SP, Penney T, McNeill S, Boscart VM, Podnieks E, Sinha SK. Best-Practice Guideline on the Prevention of Abuse and Neglect of Older Adults. Can J Aging 2016;35:242–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore C, Browne C. Emerging innovations, best practices, and evidence-based practices in elder abuse and neglect: A review of recent developments in the field. J Fam Violence 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillemer K, Burnes D, Riffin C, Lachs MS. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist 2016;56 Suppl 2:S194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ploeg J, Fear J, Hutchison B, MacMillan H, Bolan G. A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl 2009;21:187–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podnieks E, Anetzberger GJ, Wilson SJ, Teaster PB, Wangmo T. WorldView Environmental Scan on Elder Abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl 2010;22:164–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York County District Attorney’s Office NAPSA Elder Financial Exploitation Advisory Board. 2013 Nationwide Survey of Mandatory Reporting Requirements for Elderly and/or Vulnerable Persons. 2014. [Online] http://www.napsa-now.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Mandatory-Reporting-Chart-Updated-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans CS, Hunold KM, Rosen T, Platts-Mills TF. Diagnosis of Elder Abuse in U.S. Emergency Departments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The 2004 survey of state adult protective services: abuse of adults 60 years of age and older. National Center on Elder Abuse, 2004. [Online] http://www.napsa-now.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2-14-06-FINAL-60+REPORT.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blakely BE, Dolon R. Another Look at the Helpfulness of Occupational Groups in the Discovery of Elder Abuse and Neglect. J Elder Abuse Negl 2003;13:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane Update. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health 2011;33:147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beach SR, Carpenter CR, Rosen T, Sharps P, Gelles R. Screening and detection of elder abuse: Research opportunities and lessons learned from emergency geriatric care, intimate partner violence, and child abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl 2016;28:185–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallione C, Dal Molin A, Cristina FVB, Ferns H, Mattioli M, Suardi B. Screening tools for identification of elder abuse: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:2154–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, Connolly MT. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen M Screening tools for the identification of elder abuse. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2011; 18:261–70. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Center for Elder Abuse. Elder Abuse Screening Tools for Healthcare Professionals. 2016. [On-line]. http://eldermistreatment.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Elder-Abuse-Screening-Tools-for-Healthcare-Professionals.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarro AE, Wilber KH, Yonashiro J, Homeier DC. Do we really need another meeting? lessons from the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Forensic Center. Gerontologist 2010;50:702–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Safe Health Care 2008;17 Suppl 1:i13–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan E, Laupacis A, Pronovost PJ, Guyatt GH, Needham DM. How to use an article about quality improvement. JAMA 2010;304:2279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomita SK. Detection and treatment of elderly abuse and neglect: A protocol for health care professionals. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 1982;2:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper C, Barber J, Griffin M, Rapaport P, Livingston G. Effectiveness of START psychological intervention in reducing abuse by dementia family carers: randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28:881–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;347:f6276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. START (STrAtegies for RelaTives) study: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a manual-based coping strategy programme in promoting the mental health of carers of people with dementia. Health Technol Assess 2014:i–xxvi+1–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirey JA, Berman J, Salamone A, et al. Feasibility of integrating mental health screening and services into routine elder abuse practice to improve client outcomes. J Elder Abuse Negl 2015;27:254–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sirey JA, Halkett A, Chambers S, et al. PROTECT: A Pilot Program to Integrate Mental Health Treatment Into Elder Abuse Services for Older Women. J Elder Abuse Negl 2015;27:438–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartels SJ, Miles KM, Van Citters AD, Forester BP, Cohen MJ, Xie H. Improving mental health assessment and service planning practices for older adults: a controlled comparison study. Ment Health Serv Res 2005;7:213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gassoumis ZD, Navarro AE, Wilber KH. Protecting victims of elder financial exploitation: the role of an Elder Abuse Forensic Center in referring victims for conservatorship. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:790–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harries P, Davies M, Gilhooly K, Gilhooly M, Tomlinson C. Educating novice practitioners to detect elder financial abuse: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harries P, Yang H, Davies M, Gilhooly M, Gilhooly K, Thompson C. Identifying and enhancing risk thresholds in the detection of elder Med Educ 2014;14:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayslip B Jr, Reinberg J, Williams J. The impact of elder abuse education on young adults. J Elder Abuse Negl 2015;27:233–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khanlary Z, Maarefvand M, Biglarian A, Heravi-Karimooi M. The effect of a family-based intervention with a cognitive-behavioral approach on elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl 2016;28:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro AE, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH. Holding abusers accountable: an elder abuse forensic center increases criminal prosecution of financial exploitation. Gerontologist 2013;53:303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uva JL, Guttman T. Elder abuse education in an emergency medicine residency program. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:817–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uva JL, Guttman T. Elder abuse education in an emergency medicine residency program. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:817–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gassoumis ZD, Navarro AE, Wilber KH. Protecting victims of elder financial exploitation: the role of an Elder Abuse Forensic Center in referring victims for conservatorship. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:790–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carr K, Dix G, Fulmer T, et al. elder abuse assessment team in an acute hospital setting. Gerontologist 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heath JM, Dyer CB, Kerzner LJ, Mosqueda L, Murphy C. Four models of medical education about elder mistreatment. Acad Med 2002;77:1101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heath JM, Kobylarz FA, Brown M, Castano S. Interventions from home-based geriatric assessments of adult protective service clients suffering elder mistreatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1538–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heck L, Gillespie GL. Interprofessional program to provide emergency sheltering to abused elders. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2013;35:170–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matlaw JR, Spence DM. Hospital elder assessment team: a protocol for suspected cases of elder abuse and neglect. J Elder Abuse and Negl 1994;6:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosqueda L, Burnight K, Liao S, Kemp B. Advancing the field of elder mistreatment: a new model for integration of social and medical services. Gerontologist 2004;44:703–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Westley C Elder Mistreatment: Self-Learning Module. Medsurg Nurs 2005;14:133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fisher R, D’Arpino M, Dion T, et al. An elder abuse workshop for healthcare providers. Geriatr Aging 2003;6:61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCauley J, Jenckes MW, McNutt L-A. ASSERT: The Effectiveness of a Continuing Medical Education Video on Knowledge and Attitudes about Interpersonal Violence. Acad Med 2003;78:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dyer CB, Barth J, Portal B, et al. Case series of abused or neglected elders treated by an interdisciplinary geriatric team. J Elder Abuse and Negl 1999;10:131–9. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sadler P, Sorensen G. Coordination and elder abuse: development of inter-agency protocols in New South Wales. Australas J Ageing 2000;19:118–24. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brymer C, Cormack C, Spezowka K-A. Improving the care of the elderly in a rural county through education. Gerontol Geriatr Edu 1998;19:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Everson NC. Teaching banks how to protect their older customers. Aging 1996:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones J, Dougherty J, Schelble D, Cunningham W. Emergency department protocol for the diagnosis and evaluation of geriatric abuse. Ann Emerg Med 1988;17:1006–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Payne BK. Elder physical abuse and failure to report cases: Similarities and differences in case type and the justice system’s response. Crime & Delinquency 2013;59:697–717. [Google Scholar]

- 73.University of Southern California. Elder Abuse Multidisciplinary Team Project. [On-line]. https://eldermistreatment.usc.edu/elder-abuse-mdt-project/. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 74.U.S. Department of Justice. MDT Guide and Toolkit. [On-line]. https://www.justice.gov/elderjustice/mdt-toolkit. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 75.Administration for Community Living. Voluntary Consensus Guidelines for State Adult Protective Service. 2016. Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration in Community Living. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE to find programs developed to combat Elder Mistreatment

Comprehensive data abstraction list of published programs (n=115) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention

Details of published programs (n=15) focusing on elder mistreatment identification, intervention, or prevention that integrate acute care hospitals