Abstract

Aim

To examine the temporal patterns of the prostate cancer burden and its association with human development.

Subject and methods

The estimates of the incidence and mortality of prostate cancer for 87 countries were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study for the period 1990 to 2016. The human development level of a country was measured using its human development index (HDI): a summary indicator of health, education, and income. The association between the burden of prostate cancer and the human development index (HDI) was measured using pairwise correlation and bivariate regression. Mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) was employed as a proxy for the survival rate of prostate cancer.

Results

Globally, 1.4 million new cases of prostate cancer arose in 2016 claiming 380,916 lives which more than doubled from 579,457 incident cases and 191,687 deaths in 1990. In 2016, the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) was the highest in very high–HDI countries led by Australia with ASIR of 174.1/100,000 and showed a strong positive association with HDI (r = 0.66); the age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR), however, was higher in low-HDI countries led by Zimbabwe with ASMR of 78.2/100,000 in 2016. Global MIR decreased from 0.33 in 1990 to 0.26 in 2016. Mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) exhibited a negative gradient (r = − 0.91) with human development index with tenfold variation globally with seven countries recording MIR in excess of 1 with the USA recording the minimum MIR of 0.10.

Conclusion

The high mortality and lower survival rates in less-developed countries demand all-inclusive solutions ranging from cost-effective early screening and detection to cost-effective cancer treatment. In tackling the rising burden of prostate cancer predictive, preventive and personalised medicine (PPPM) can play a useful role through prevention strategies, predicting PCa more precisely and accurately using a multiomic approach and risk-stratifying patients to provide personalised medicine.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Incidence, Mortality, Mortality-to-incidence ratio, Human development index, Predictive preventive personalised medicine, Precision medicine

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the leading causes of death in males worldwide, and its incidence is increasing in both developed and developing countries alike in the last three decades [1]. While the incidence of prostate cancer is high in developed countries such as the USA and European countries, the survival rates, however, are lower in the less-developed countries [2, 3]. Prostate cancer is mostly diagnosed in older ages with a large percent of it being diagnosed as indolent and a significant portion of older patients die with prostate cancer rather than due to it [4]. There are wide disparities in survival rates in world regions which largely depend upon the stage of disease presentation, healthcare infrastructure, and availability of treatment options [5].

This paper examines the burden of prostate cancer (incidence and mortality) in 87 countries for the period 1990–2016 paying careful attention to the temporal patterns of prostate cancer burden and its association with human development. The estimates of prostate cancer burden were procured from the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study [1, 6], and the human development of a country was measured using its human development index (HDI) compiled by United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Against previous studies limited by the number of countries (or regions) or time period examined, we investigate prostate cancer burden in a large set of countries (87 countries) and pay careful attention to the temporal patterns of prostate cancer burden. In addition to investigating the incidence and mortality of prostate cancer, we also examine mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) of prostate cancer which has been demonstrated to be a proxy indicator of 5-year survival rates [7–10]. Although MIR is an imperfect proxy for survival rate, yet, we conjecture that it can reveal patterns of relative survival rates across countries as per their development status. In this study, we employed the human development index (HDI) as the indicator of development in the place of the socio-demographic index (SDI) employed by GBD. This is because SDI is a composite measure of income, education, and fertility whereas HDI is the indicator of income, education, and life expectancy, and as cancer burden has been found to have positive association with age, life expectancy seems to be a better indicator than fertility while describing the prostate cancer burden. Examination of past trends of incidence, mortality, and survival rate (proxied using MIR) and its association with HDI can reveal the rate of our progress in the fight against one of the diseases causing substantial mortality and morbidity in males worldwide. Moreover, PPPM approaches to cancer management will first require the data or the estimates as to the regions or countries in which cancer burden is rising the fastest and to identify the countries in which the survival rates are the worst. Identifying the most-burdened countries in terms of incidence, mortality, and survival can help in accelerating PPPM practices. Secondly, our analysis can illuminate the role of human development (and its components) in ameliorating the burden of prostate cancer. Thirdly, developed countries seem to be in a better position to offer precision medicine to tackle the cancer burden. If the survival rates proxied by MIR can be better predicted by human development measured using HDI, burdened countries must strive for broader human development rather than just boosting per capita income levels.

Data and methods

The estimates of incidence and mortality of prostate cancer (both all-age numbers and age-standardised rates) were procured from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2016 study for the period 1990–2016 [6, 11].1 The Global Burden of Disease 2016 study provides age-, sex-, and year-wise estimates of incidence, prevalence, and mortality for 264 causes for 195 countries for the period 1990 to 2016 [6]. The Global Burden of Disease provides estimates of three additional population health metrics: years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature death, years lived with disability (YLDs), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

GBD estimation framework

To obtain estimates of incidence, mortality, and DALYs, GBD procured data from various sources such as vital registration, cancer registries, and verbal autopsies, which goes through multiple modelling steps detailed elsewhere [1, 6]; here, we briefly discuss how GBD arrives at the estimates of the incidence and mortality of prostate cancer. The GBD methodology starts with the processing of incidence and mortality data from cancer registries and the processed data was matched by cancer, age, sex, year, and location to generate crude mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIR). Second, the crude mortality-to-incidence ratios were used as input for a three-step modelling approach using the general spatio-temporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR) along with socio-demographic index (SDI) as a covariate in the linear-step mixed effects model using a logit link function to obtain the final MIR. In the third step, the incidence from cancer registries was multiplied with mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIR) obtained in the second step to generate mortality estimates; these mortality estimates were then used as input for cause-of-death ensemble model (CodeM) to obtain the final mortality estimates [6, 13]. The CodeM model was developed by Foreman et al. [13] to arrive at the cause-specific mortality estimates; it is an ensemble modelling approach in which a large number of models are tested for their predictive validity before arriving at the final mortality estimates [13]. In this modelling approach, only those covariates are chosen which have been found to have a plausible relationship with the particular cause of death. The relationship need not be causal but at least plausible. Few of the covariates used to model prostate cancer mortality in CodeM were as follows: education, lag-distributed income, socio-demographic index, and healthcare access and quality index [6]. The final mortality estimates were divided by the MIR estimates obtained in the second step to generate the final incidence estimates [6, 12].

Mortality, incidence, and mortality-to-incidence ratio

In this study, we procured estimates of incidence and mortality of prostate cancer for the period 1990 to 2016. Both all-age prostate cancer numbers and age-standardised rates were employed to describe the PCa burden. We employed mortality-to-incidence ratio to proxy for the survival rate of prostate cancer which has been demonstrated to be a proxy of the survival rate of different neoplasia [7–10]. Although an imperfect proxy of survival rates, it can provide useful direction as to the relative survival rates of PCa across countries. Mortality-to-incidence ratio was calculated directly from the ratio of crude mortality rate and crude incidence rate obtained from GBD 2016. In this study, we examined prostate cancer for 87 countries which had more than 1000 incident cases in 2016. It was done to focus on heavily-burdened countries as well as to prevent skewness in MIR values due to very low values of incidence or mortality, which could have resulted in too high or too low MIR values. Following the GBD convention, we reported the estimates of incidence and mortality with 95% uncertainty intervals (UI)2 inside the square brackets and where percent change was reported alone, it was calculated from the mean estimates.

Development level of a country

The development level of a country was measured using its human development index (HDI)—a composite measure of three indicators of development: health (life expectancy at birth), education (mean years of schooling and expected number of years of schooling),3 and income (gross national income (GNI) per capita). For HDI calculation, each indicator gets scaled on a 0 to 1 scale with 0 corresponding to the lowest value and 1 corresponding to the highest value, and the final HDI value of a country was calculated by taking the geometric mean of the health, education, and income indices [14]. Data pertaining to the human development index (HDI) for the period 1990 to 2015 was procured from the UNDP database. For descriptive as well as analytical purposes, countries were categorised into four groups as per UNDP classification in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800, 36 countries), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799, 26 countries), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669, 15 countries), and low (HDI < 0.550, 9 countries) HDI categories.4 In this paper, we employ the term “developed” for countries in high- and very high–HDI categories and “developing” for countries in low- and medium-HDI categories.

In addition to defining PCa burden as per development measured by HDI, we also examined the association between the mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR), and income per capita and life expectancy of males. We procured data of GNI per capita (at 2010 USD) and life expectancy of males from World Development Indicators (WDI) database of the World Bank. The entire data analysis was conducted using MS Excel 2016, Python 3.6, and Stata 13.0.

Results

Global temporal patterns: 1990–2016

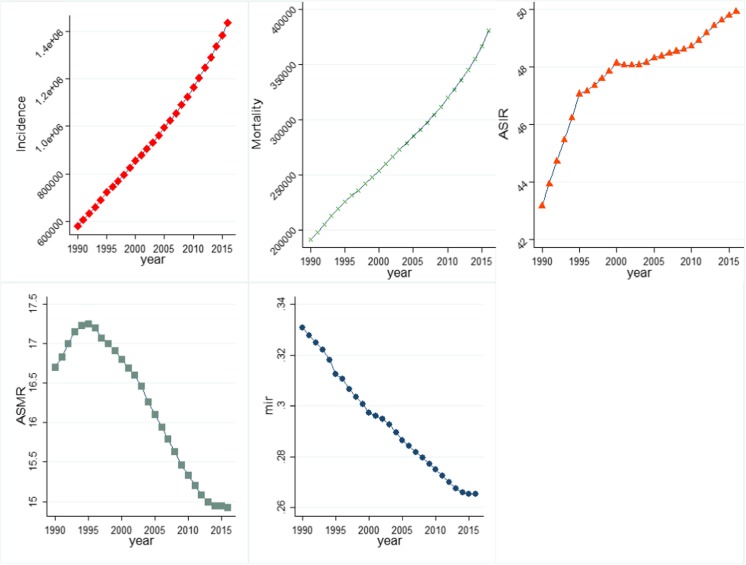

Globally, prostate cancer resulted in 380,916 [95% uncertainty interval (UI), 320,808–412,868] deaths in 2016 from 191,687 [168886–209,254] in 1990 (Fig. 1). The incidence of prostate cancer more than doubled from 579,457 [521564–616,107] in 1990 to 1.4 million [1.3–1.6 million] incident cases in 2016. Against the rising number of deaths due to prostate cancer, age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR) fallen from 16.7 [14.9–18.3] in 1990 to 14.9 [12.7–16.2] per 100,000 males in 2016, whereas the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) rose from 43.2 [38.8–46.1] per 100,000 males in 1990 to 49.9 [45.0–56.1] in 2016. Global mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) witnessed a decline from 0.33 in 1990 to 0.26 in 2016. Figure 1 illustrates that all-age incidence and deaths due to prostate cancer increased continuously between 1990 and 2016, whereas MIR exhibited a declining trend over the same period. ASIR increased sharply in the early 1990s before undergoing a flattened trajectory in the time period thereafter. ASMR too decreased in the study period before peaking around mid-1990s.

Fig. 1.

Temporal movement of global prostate cancer burden in terms of key indicators, 1990–2016: a incidence, b mortality, c ASIR, d ASMR, e MIR. Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. Data source: Global Burden of Disease 2016 study

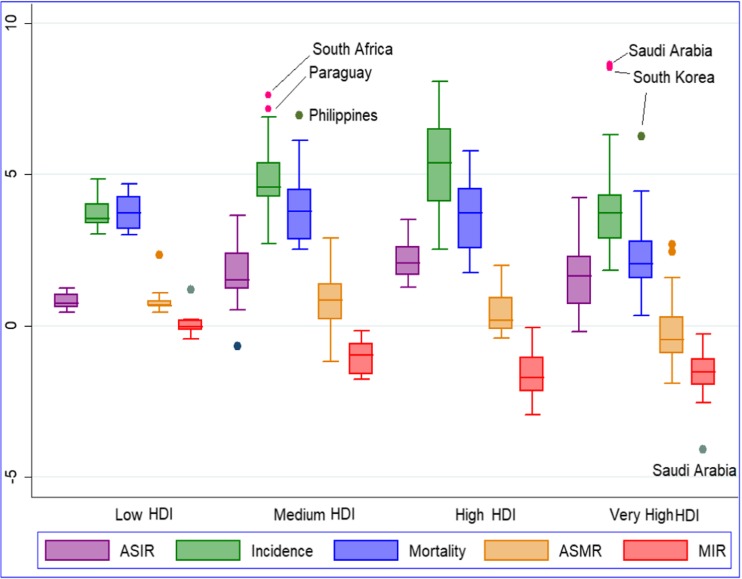

The sample of 87 countries in this study accounted for 1,402,465 incident cases and 358,056 deaths which contributed towards 98% of global incidence and deaths due to prostate cancer in 2016. Incidence increased in all the 87 countries, whereas ASIR increased in all countries except for two countries: Ghana and the USA. Deaths due to PCa also increased in all the sample countries, whereas ASMR increased in 52 of the 87 countries—21 of the 24 less-developed countries (low/medium HDI) and 31 of 62 developed countries (high/very high HDI) (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Country-wise prostate cancer burden in 2016

| Location | Incidence | Deaths | ASIR | ASMR | MIR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High HDI | |||||

| Algeria |

1434 [1099–1896] |

857 [638–1178] |

11.74 [9.04–15.62] |

7.57 [5.69–10.38] |

0.6 |

| Belarus |

2959 [2301–3477] |

869 [664–1086] |

59.32 [47.09–69.7] |

19.22 [14.92–23.9] |

0.29 |

| Brazil |

47,681 [45015–64,039] |

19,104 [17893–25,276] |

64.92 [61.36–85.82] |

30.17 [28.28–39.12] |

0.4 |

| Bulgaria |

2299 [1926–2798] |

1000 [799–1281] |

40.34 [33.83–48.35] |

17.74 [14.34–22.53] |

0.44 |

| China |

111,604 [88324–138,314] |

35,327 [26800–44,281] |

16.06 [12.61–20.05] |

6.15 [4.68–7.62] |

0.32 |

| Colombia |

9718 [8452–11,214] |

3359 [2788–3945] |

60.32 [53.09–69.23] |

24.01 [19.97–28.14] |

0.35 |

| Costa Rica |

1386 [1055–1523] |

506 [354–580] |

67.46 [49.78–74.33] |

26.65 [18.21–30.48] |

0.37 |

| Cuba |

7828 [6200–8602] |

3068 [2417–3494] |

102.78 [81.36–112.8] |

40.28 [31.71–46] |

0.39 |

| Dominican Republic |

3011 [2199–3518] |

1665 [1155–2008] |

85.47 [61.99–99.91] |

48.8 [33.86–58.72] |

0.55 |

| Ecuador |

2464 [2203–3167] |

1190 [1020–1492] |

47.02 [42.07–60.68] |

24.28 [20.84–30.16] |

0.48 |

| Iran |

7411 [4990–8640] |

2766 [1773–3559] |

31.21 [21.32–36.6] |

13.48 [8.78–17.19] |

0.37 |

| Jamaica |

1432 [789–1752] |

794 [416–1087] |

113.08 [62.31–138.58] |

61.98 [32.56–84.84] |

0.55 |

| Kazakhstan |

1172 [830–1352] |

443 [304–568] |

22.37 [15.63–25.76] |

10.15 [6.98–12.85] |

0.38 |

| Lebanon |

1810 [1143–2188] |

534 [324–698] |

73.53 [46.54–88.62] |

24.41 [14.92–31.56] |

0.29 |

| Malaysia |

2104 [1668–2553] |

721 [551–888] |

22.92 [17.83–27.29] |

9.32 [6.91–11.21] |

0.34 |

| Mexico |

25,183 [23725–31,533] |

7261 [6725–8997] |

60.34 [56.85–75.3] |

18.75 [17.36–23.2] |

0.29 |

| Panama |

1607 [1169–1790] |

403 [283–485] |

106.9 [77.51–119.29] |

27.77 [19.39–33.38] |

0.25 |

| Peru |

4712 [3835–6183] |

2194 [1633–3008] |

46.63 [38.02–61.17] |

23.49 [17.55–32.35] |

0.47 |

| Serbia |

2975 [2363–3874] |

1278 [1049–1709] |

47.33 [37.74–61.44] |

21.31 [17.56–28.64] |

0.43 |

| Sri Lanka |

1165 [948–1565] |

547 [392–798] |

13.54 [11.08–18.41] |

7.25 [5.25–10.6] |

0.47 |

| Thailand |

6057 [3882–7180] |

2597 [1703–3244] |

17.71 [11.21–21.02] |

8.4 [5.45–10.49] |

0.43 |

| Tunisia |

1019 [602–1234] |

558 [302–776] |

24.28 [14.24–29.6] |

14.55 [7.98–20.19] |

0.55 |

| Turkey |

9301 [7575–11,784] |

3694 [2742–4810] |

33.67 [27.24–42.43] |

14.91 [11.08–19.35] |

0.4 |

| Ukraine |

9872 [8555–12,185] |

3788 [2743–5297] |

38.12 [33.09–47.61] |

15.27 [11.19–21.97] |

0.38 |

| Uruguay |

1624 [1428–1836] |

750 [640–866] |

84.64 [74.63–95.31] |

38.79 [33.24–44.62] |

0.46 |

| Venezuela |

10,341 [8106–11,543] |

2821 [2097–3562] |

108.26 [83.95–121.22] |

35.6 [26.71–44.67] |

0.27 |

| Low HDI | |||||

| Cote d’Ivoire |

1564 [773–2025] |

1913 [909–2588] |

44.55 [20.86–57.91] |

59.24 [27.09–79.97] |

1.22 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo |

2468 [1447–3093] |

2584 [1530–3429] |

26.17 [15.1–32.84] |

29.57 [17.55–39.85] |

1.05 |

| Ethiopia |

6186 [2488–8295] |

7020 [2501–10,347] |

37.35 [14.97–49.74] |

45.1 [16.2–65.27] |

1.13 |

| Haiti |

1357 [996–1693] |

1274 [917–1694] |

63.93 [46.65–79.18] |

64.11 [47.08–84.21] |

0.94 |

| Madagascar |

1432 [584–1915] |

1313 [472–1975] |

39.61 [16.07–52.79] |

38.79 [14.08–56.92] |

0.92 |

| Nigeria |

15,474 [6348–20,883] |

11,410 [4812–17,297] |

58.63 [26.27–77.54] |

50.8 [23.98–72.99] |

0.74 |

| Tanzania |

3439 [1388–4655] |

3732 [1399–5393] |

40.97 [16.43–55.38] |

47.49 [17.99–68.17] |

1.09 |

| Uganda |

2892 [2255–3519] |

3165 [2402–3991] |

64.17 [50.16–78.68] |

75.5 [57.62–95.39] |

1.09 |

| Zimbabwe |

1304 [610–1671] |

1533 [666–2185] |

62.87 [29.24–80.26] |

78.19 [34.77–109.54] |

1.17 |

| Medium HDI | |||||

| Bangladesh |

2897 [2260–3999] |

1949 [1502–2756] |

7.21 [5.75–9.9] |

5.15 [4.02–7.2] |

0.67 |

| Bolivia |

1378 [1042–1710] |

920 [670–1186] |

41.69 [31.44–51.74] |

28.65 [20.97–36.82] |

0.67 |

| Egypt |

2855 [2322–4230] |

1496 [1090–2330] |

12.9 [9.98–20.04] |

8.07 [5.68–13.15] |

0.52 |

| Ghana |

1054 [862–1494] |

1096 [874–1565] |

24.95 [20.62–34.78] |

29.53 [23.77–40.74] |

1.04 |

| Guatemala |

1247 [1098–1424] |

823 [588–1077] |

34.3 [30.06–39.34] |

23.95 [17.33–31.02] |

0.66 |

| India |

32,726 [26011–39,749] |

20,954 [16143–25,842] |

9.01 [7.1–10.84] |

6.7 [5.1–8.05] |

0.64 |

| Indonesia |

15,732 [10337–18,450] |

7336 [4635–8854] |

24.29 [15.87–28.48] |

14 [8.92–16.87] |

0.47 |

| Kenya |

1174 [695–1339] |

823 [466–1050] |

16.95 [10.02–19.31] |

13.36 [7.74–16.9] |

0.7 |

| Morocco |

1600 [938–1987] |

933 [576–1160] |

14.06 [8.83–17.01] |

9.14 [6.1–11.13] |

0.58 |

| Myanmar |

2572 [1688–3075] |

1756 [1079–2176] |

19.81 [12.82–23.77] |

15.65 [9.6–19.34] |

0.68 |

| Pakistan |

5794 [3099–7364] |

3308 [1864–4315] |

12.9 [7.33–16.11] |

8.14 [4.93–10.27] |

0.57 |

| Paraguay |

1004 [667–1160] |

526 [346–653] |

50.58 [33.7–58.48] |

29.23 [19.34–36.09] |

0.52 |

| Philippines |

6397 [5430–7306] |

3534 [2804–4261] |

32.17 [27.31–36.63] |

21.97 [17.61–26.5] |

0.55 |

| South Africa |

9736 [7789–12,031] |

3825 [3012–4836] |

77.2 [60.81–94.72] |

36.55 [28.83–45.73] |

0.39 |

| Vietnam |

2853 [1964–3363] |

1820 [1220–2201] |

10.32 [7.01–12.24] |

7.03 [4.71–8.49] |

0.64 |

| Very high HDI | |||||

| Argentina |

12,768 [11391–15,740] |

4936 [4263–6176] |

66.07 [58.92–81.93] |

26.97 [23.34–33.92] |

0.39 |

| Australia |

28,519 [23426–35,056] |

3987 [3424–4921] |

174.1 [144.16–213.37] |

23.8 [20.49–29.2] |

0.14 |

| Austria |

8304 [7075–9671] |

1405 [1096–1629] |

124.19 [106.9–143.6] |

20.5 [15.99–23.63] |

0.17 |

| Belgium |

10,182 [8775–15,573] |

2079 [1718–3456] |

116.84 [100.66–179.03] |

22.56 [18.75–37.7] |

0.2 |

| Canada |

28,020 [22636–36,426] |

5652 [4834–7161] |

107.46 [86.99–139.99] |

22.05 [18.92–27.96] |

0.2 |

| Chile |

6710 [5093–7505] |

2428 [1639–3222] |

77.16 [58.22–86.41] |

29.41 [19.77–38.95] |

0.36 |

| Croatia |

2364 [1769–2923] |

819 [602–986] |

74.19 [55.37–90.33] |

26.31 [19.26–31.52] |

0.35 |

| Czech Republic |

6913 [4920–8627] |

1590 [1144–1855] |

88.77 [63.12–109.72] |

22.53 [15.92–26.1] |

0.23 |

| Denmark |

5261 [3535–5988] |

1404 [952–1691] |

112.82 [76.18–127.8] |

31.4 [21.26–37.61] |

0.27 |

| Finland |

6363 [5081–7404] |

997 [767–1171] |

138.06 [109.94–159.54] |

22.37 [17.11–26.07] |

0.16 |

| France |

53,184 [45717–64,514] |

12,761 [10871–15,751] |

104.79 [90.34–126.65] |

22.86 [19.64–28.23] |

0.24 |

| Germany |

92,890 [79412–110,335] |

16,156 [13461–19,988] |

127.63 [109.7–149.48] |

21.37 [17.91–26.27] |

0.17 |

| Greece |

7354 [6419–11,160] |

2178 [1867–3215] |

73.24 [63.87–114.39] |

18.36 [15.7–27.53] |

0.3 |

| Hungary |

3865 [3156–5232] |

1368 [1137–1855] |

57.13 [47.09–76.45] |

21.72 [18.11–29.53] |

0.35 |

| Ireland |

3434 [2878–4002] |

683 [532–834] |

121.54 [101.74–141.59] |

25.51 [20.02–30.96] |

0.2 |

| Israel |

1966 [1730–2740] |

586 [452–903] |

47.75 [41.89–67.16] |

13.74 [10.52–21.36] |

0.3 |

| Italy |

57,726 [49449–69,184] |

10,179 [8550–12,144] |

107.99 [92.32–130.77] |

16.73 [14.22–20] |

0.18 |

| Japan |

73,795 [63205–80,381] |

12,995 [10452–14,202] |

53.77 [46.81–58.79] |

8.76 [7.13–9.56] |

0.18 |

| Latvia |

1048 [578–1241] |

367 [180–450] |

82.57 [45.67–97.64] |

29.64 [14.49–36.02] |

0.35 |

| Lithuania |

3038 [1622–3622] |

534 [263–626] |

163.55 [88.73–195.29] |

28.26 [13.99–32.98] |

0.18 |

| Netherlands |

18,465 [15016–21,482] |

3267 [2605–3828] |

136.71 [110.79–158.55] |

25.57 [20.38–29.76] |

0.18 |

| New Zealand |

4695 [3842–5705] |

701 [592–893] |

150.93 [124.3–182.46] |

22.88 [19.29–29.17] |

0.15 |

| Norway |

6024 [4568–6865] |

1158 [837–1362] |

158.42 [120.46–180.25] |

30.88 [22.36–36.26] |

0.19 |

| Poland |

13,554 [10720–16,192] |

5322 [4280–6322] |

54.79 [43.82–65.64] |

23.17 [18.82–27.4] |

0.39 |

| Portugal |

7784 [6816–10,990] |

2256 [1927–3129] |

90.52 [79.45–129.46] |

24.55 [21.08–34.15] |

0.29 |

| Romania |

8201 [6634–10,384] |

2181 [1838–2705] |

59.55 [48.36–75.21] |

15.98 [13.45–19.8] |

0.27 |

| Russian Federation |

41,994 [33488–48,671] |

11,836 [8062–16,085] |

56.34 [45.69–65.29] |

17.79 [12.36–23.9] |

0.28 |

| Saudi Arabia |

1352 [1071–1680] |

403 [296–494] |

21.01 [16.37–25.73] |

8.99 [6.57–10.87] |

0.3 |

| Slovakia |

2128 [1263–2756] |

626 [362–792] |

68.85 [41.04–88.76] |

22.5 [13.11–28.35] |

0.29 |

| Slovenia |

1160 [792–1401] |

449 [276–548] |

72.71 [49.2–87.72] |

29.57 [17.81–35.92] |

0.39 |

| South Korea |

10,943 [7083–13,259] |

2262 [1222–3232] |

38.08 [24.15–46.09] |

9.2 [4.88–12.98] |

0.21 |

| Spain |

24,184 [20966–34,860] |

7355 [6272–10,646] |

65.05 [56.29–94.21] |

17.8 [15.21–25.94] |

0.3 |

| Sweden |

12,792 [10009–14,418] |

2731 [2034–3216] |

153.79 [121.7–172.1] |

31.4 [23.38–36.94] |

0.21 |

| Switzerland |

8497 [6964–9972] |

1513 [1108–2045] |

132.35 [108.26–155.52] |

22.75 [16.71–30.67] |

0.18 |

| UK |

49,432 [45379–55,963] |

13,636 [12471–15,441] |

97.17 [89.54–109.82] |

25.5 [23.46–28.8] |

0.28 |

| USA |

371,672 [348609–485,368] |

35,468 [32984–48,659] |

172.51 [161.85–225.02] |

16.98 [15.8–23.23] |

0.1 |

| Global |

1,435,742 [1293395–1,618,655] |

380,916 [320808–412,868] |

49.93 [44.99–56.05] |

14.92 [12.7–16.15] |

0.27 |

| Puerto Rico |

2579 [2292–3248] |

653 [563–810] |

116.94 [104.05–147.45] |

28.86 [24.92–35.64] |

0.25 |

Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. Data Source: Global Burden of Disease 2016 study. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550)

Fig. 2.

HDI-group wise annual percentage change of key indicators of prostate cancer burden over 1990–2016. Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. Data pertains to low HDI (15 countries), medium HDI (18 countries), high HDI (31 countries), and very high HDI (36 countries) for the period 1990 to 2016 and is procured from Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550)

Incidence and mortality in 2016

In terms of incidence, very high– and high-HDI countries recorded the highest all-age incidence and deaths with the USA recording the highest incidence of 371,672 [348,609–485,368] followed by China with 111,604 [88324–138,314] newly diagnosed cases in 2016 (Table 2). The age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) was again the highest in developed countries (high/very high HDI) with all the top ten countries belonged to the very high–HDI category. With an ASIR of 174.1 [144.2–213.4] per 100,000 males, Australia recorded the largest ASIR in 2016 closely followed by the USA with ASIR of 172.5 [161.9–225.0] per 100,000 males. The populous countries of India and China recorded low ASIR of 16.1 [12.6–20.1] and 9.0 [7.1–10.8] per 100,000 males, respectively, in 2016.

Table 2.

Annual percentage change of key indicators: 1990–2016

| Country | ASIR | ASMR | Incidence | Mortality | MIR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High HDI | |||||

| Algeria | 1.5370 | 0.0352 | 6.1951 | 4.6786 | − 1.4280 |

| Belarus | 3.0497 | 1.9444 | 4.0876 | 3.0730 | − 0.9747 |

| Brazil | 2.0030 | 0.1351 | 6.3735 | 4.5349 | − 1.7284 |

| Bulgaria | 2.0767 | 0.9355 | 2.6348 | 1.7637 | − 0.8488 |

| China | 2.2075 | − 0.2099 | 5.7682 | 3.1788 | − 2.4482 |

| Colombia | 1.6526 | − 0.1664 | 5.5033 | 3.5321 | − 1.8684 |

| Costa Rica | 2.0644 | 0.1097 | 6.7295 | 4.8350 | − 1.7750 |

| Cuba | 1.8735 | 0.7753 | 4.0909 | 2.9783 | − 1.0688 |

| Dominican Republic | 2.8552 | 1.6420 | 6.6670 | 5.7726 | − 0.8385 |

| Ecuador | 1.2697 | − 0.4062 | 5.2661 | 3.5576 | − 1.6230 |

| Iran | 3.5092 | 1.0339 | 7.6685 | 5.0377 | − 2.4434 |

| Jamaica | 2.5983 | 1.9901 | 4.5921 | 4.0185 | − 0.5485 |

| Kazakhstan | 1.8702 | 0.7167 | 3.3073 | 2.0032 | − 1.2624 |

| Lebanon | 3.1693 | 0.1119 | 8.0772 | 4.8950 | − 2.9444 |

| Malaysia | 2.6567 | − 0.0735 | 7.1554 | 4.1233 | − 2.8296 |

| Mexico | 2.4963 | 0.2146 | 6.2223 | 3.9017 | − 2.1846 |

| Panama | 2.5969 | 0.2532 | 6.5112 | 4.3381 | − 2.0403 |

| Peru | 1.3215 | − 0.0015 | 5.2190 | 4.1004 | − 1.0632 |

| Serbia | 1.3281 | 0.4903 | 3.1566 | 2.5563 | − 0.5820 |

| Sri Lanka | 1.7452 | − 0.3367 | 4.3141 | 2.0258 | − 2.1937 |

| Thailand | 1.9844 | − 0.1334 | 6.4189 | 4.3276 | − 1.9651 |

| Tunisia | 1.5165 | − 0.3082 | 5.0557 | 3.2425 | − 1.7259 |

| Turkey | 2.1336 | − 0.1153 | 5.0437 | 2.5085 | − 2.4135 |

| Ukraine | 1.6762 | 1.3357 | 2.5308 | 2.4640 | − 0.0652 |

| Uruguay | 2.1108 | 0.7237 | 3.2429 | 2.1144 | − 1.0931 |

| Venezuela | 3.2980 | 1.2585 | 7.4094 | 5.2107 | − 2.0470 |

| Low HDI | |||||

| Cote d’Ivoire | 0.6120 | 0.5772 | 3.7088 | 3.6024 | − 0.1026 |

| Dem. Rep of Congo | 0.4779 | 0.6493 | 4.0655 | 4.2807 | 0.2068 |

| Ethiopia | 0.4487 | 0.6486 | 3.5497 | 3.7347 | 0.1786 |

| Haiti | 0.7482 | 0.8132 | 3.0753 | 3.1202 | 0.0436 |

| Madagascar | 0.7876 | 0.6534 | 3.3821 | 3.1957 | − 0.1803 |

| Nigeria | 0.7063 | 0.4438 | 3.4433 | 2.9967 | − 0.4318 |

| Tanzania | 1.0269 | 0.8232 | 4.8371 | 4.6797 | − 0.1501 |

| Uganda | 1.1690 | 1.0749 | 4.0247 | 3.9821 | − 0.0409 |

| Zimbabwe | 1.2391 | 2.3363 | 3.0327 | 4.2616 | 1.1927 |

| Medium HDI | |||||

| Bangladesh | 0.5294 | − 1.1923 | 4.3538 | 2.6201 | − 1.6613 |

| Bolivia | 1.3083 | 0.1909 | 5.3770 | 4.4910 | − 0.8407 |

| Egypt | 1.5038 | − 0.0255 | 4.4732 | 2.6088 | − 1.7845 |

| Ghana | − 0.6882 | − 0.7540 | 2.7137 | 2.5305 | − 0.1784 |

| Guatemala | 3.6480 | 2.7836 | 7.6339 | 6.9690 | − 0.6177 |

| India | 1.1414 | 0.7761 | 4.5904 | 3.8666 | − 0.6921 |

| Indonesia | 2.0606 | 1.4347 | 5.1643 | 4.0762 | − 1.0347 |

| Kenya | 1.2254 | 0.8313 | 4.2493 | 3.6296 | − 0.5944 |

| Morocco | 1.4743 | 0.4662 | 5.2118 | 4.1119 | − 1.0455 |

| Myanmar | 1.6124 | 1.3752 | 4.1724 | 3.6429 | − 0.5083 |

| Pakistan | 1.5770 | 1.1039 | 4.3929 | 3.7858 | − 0.5816 |

| Paraguay | 2.8132 | 1.2018 | 6.9169 | 5.1893 | − 1.6159 |

| Philippines | 3.5621 | 2.8943 | 7.1606 | 6.1234 | − 0.9679 |

| South Africa | 2.3915 | 1.0385 | 4.7190 | 2.9565 | − 1.6831 |

| Vietnam | 1.4199 | 0.2543 | 4.0471 | 2.8474 | − 1.1530 |

| Very high HDI | |||||

| Argentina | 1.8956 | 0.3017 | 3.8181 | 2.3581 | − 1.4063 |

| Australia | 1.5229 | − 0.9585 | 4.5671 | 2.5899 | − 1.8909 |

| Austria | 0.5544 | − 0.7122 | 2.6404 | 1.7704 | − 0.8477 |

| Belgium | 0.3448 | − 1.8972 | 2.1041 | 0.3842 | − 1.6845 |

| Canada | 0.2374 | − 1.5985 | 3.0923 | 1.5422 | − 1.5036 |

| Chile | 2.6958 | 0.8928 | 6.2340 | 4.4388 | − 1.6898 |

| Croatia | 1.2041 | 0.2889 | 2.8559 | 2.2125 | − 0.6255 |

| Czech Republic | 1.7677 | 0.0055 | 3.7286 | 2.0422 | − 1.6258 |

| Denmark | 2.1633 | − 0.0293 | 3.7502 | 1.4404 | − 2.2263 |

| Finland | 1.5982 | − 1.1071 | 4.4030 | 1.9276 | − 2.3710 |

| France | 0.8855 | − 1.5033 | 2.9512 | 1.0339 | − 1.8624 |

| Germany | 1.6615 | − 0.7884 | 3.9866 | 1.8847 | − 2.0213 |

| Greece | 1.6684 | − 0.1156 | 3.6237 | 2.6293 | − 0.9595 |

| Hungary | 0.7166 | − 0.8255 | 1.8188 | 0.3243 | − 1.4677 |

| Ireland | 2.0496 | − 0.6039 | 4.2290 | 1.5951 | − 2.5271 |

| Israel | 0.3349 | − 1.4455 | 3.7059 | 2.1005 | − 1.5481 |

| Italy | 1.0676 | − 0.1256 | 2.8900 | 2.6072 | − 0.2748 |

| Japan | 2.8300 | 0.1138 | 6.3137 | 4.1201 | − 2.0634 |

| Latvia | 3.0982 | 2.4482 | 3.8680 | 3.4974 | − 0.3568 |

| Lithuania | 4.2389 | 2.6860 | 5.1480 | 3.9244 | − 1.1637 |

| Netherlands | 1.6428 | − 0.5229 | 4.0780 | 1.9963 | − 2.0001 |

| New Zealand | 0.6429 | − 0.8797 | 3.4024 | 2.4002 | − 0.9692 |

| Norway | 1.8829 | − 0.7809 | 3.3081 | 0.6631 | − 2.5603 |

| Poland | 2.7000 | 0.8459 | 4.8185 | 2.9692 | − 1.7643 |

| Portugal | 0.6925 | − 0.8812 | 2.5879 | 1.6610 | − 0.9035 |

| Romania | 2.5626 | 1.0268 | 3.5632 | 2.3499 | − 1.1715 |

| Russian Federation | 2.3975 | 1.6041 | 3.9786 | 3.4854 | − 0.4743 |

| Saudi Arabia | 3.5521 | 0.2771 | 8.6369 | 4.1770 | − 4.1054 |

| Slovakia | 2.0880 | 0.5503 | 3.7948 | 2.0754 | − 1.6565 |

| Slovenia | 1.7295 | 0.1148 | 4.4834 | 3.1370 | − 1.2887 |

| South Korea | 3.4242 | 0.9575 | 8.5278 | 6.2751 | − 2.0757 |

| Spain | 0.5609 | − 1.1851 | 2.8579 | 1.7760 | − 1.0519 |

| Sweden | 1.3622 | − 0.4195 | 2.6529 | 1.0865 | − 1.5260 |

| Switzerland | 0.3721 | − 1.8175 | 2.4766 | 0.5167 | − 1.9125 |

| UK | 1.3179 | − 0.5054 | 2.9965 | 1.5764 | − 1.3788 |

| USA | − 0.1869 | − 1.8532 | 2.0685 | 0.5382 | − 1.4993 |

| No HDI | |||||

| Puerto Rico | 1.1453 | − 0.4420 | 2.6613 | 1.2322 | − 1.3920 |

Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. Data pertaining to low HDI (15 countries), medium HDI (18 countries), high HDI (31 countries), and very high HDI (36 countries) for the period 1990 to 2016. Data source: Authors’ calculation from Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550)

In terms of mortality, the developed countries (high/very high HDI) occupied eight of the top ten positions with the USA ranked first with 35,468 [32,984–48,659] deaths followed by China with 35,327 [26,800–44,281] deaths in 2016. India (medium HDI) and Nigeria (low HDI) were two exceptions in top ten with prostate cancer claiming 20,954 [16,144–25,842] and 11,410 [95% UI, 4812–17,297] lives, respectively in 2016 (Table 2). The age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR) exhibited different patterns as per human development in comparison to ASIR with seven of the top ten countries belonged to the low-HDI category in 2016. High ASMR was concentrated in regions of Africa with Zimbabwe recording the highest ASMR of 78.2/100,000 [34.8–109.5] closely followed by Uganda with ASMR of 75.5 [57.6–95.4] per 100,000 in 2016. India and China were present at the bottom with ASMR of 6.7 [5.1–8.0] and 6.2 [4.7–7.6] per 100,000 males, respectively in 2016.

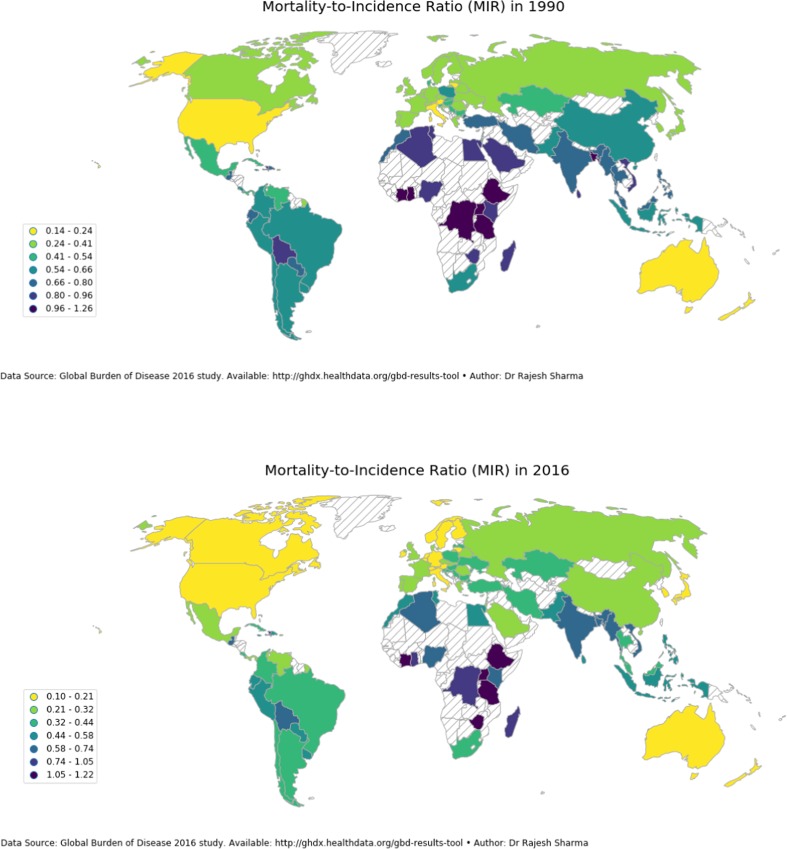

Mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) in 1990 and 2016

MIR exhibited different patterns of association with HDI in comparison to the incidence and mortality with all nine low-HDI countries present at the top (Table 1). Seven low-HDI countries registered MIR in excess of 1 in 2016 with Cote d’Ivoire recording the highest MIR of 1.22 followed by Zimbabwe and Ethiopia with MIR of 1.17 and 1.13, respectively, in 2016. Nineteen of the bottom 20 countries belonged to the very high–HDI category with the USA recording the lowest MIR of 0.10 in 2016. Between 1990 and 2016, there was not much improvement recorded in low HDI-countries; a significant reduction, however, was recorded in other HDI categories (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Geographical distribution of MIR in sample countries a 1990 and b 2016. MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. MIR is calculated as the ratio of all-age crude mortality rate to all-age crude incidence rate which was procured from Global Burden of Disease study 2016

Prostate cancer burden and factors affecting PCa burden

Prostate cancer burden exhibited a different pattern of association with HDI as per the metric used for measuring the cancer burden (Table 3). MIR had a stronger correlation with HDI (r = − 0.91) than male life expectancy (r = − 0.80) and income per capita (r = − 0.78). ASIR was predicted better by income per capita (R2 = 0.59, p < 0.01) than the all-age incidence number (R2 = 0.12, p < 0.01). The age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR), however, was predicted better by life expectancy (R2 = 0.08, p < 0.01) than by income per capita (R2 = 0.0001, p < 0.01) and even proved to be a better predictor than the human development index (R2 = 0.02, p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Correlation of indicators of prostate cancer burden and HDI

| Income | LE_male | HDI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Incidence | 0.3473 | 0.1942 | 0.2536 |

| Mortality | 0.2330 | 0.1269 | 0.1604 |

| ASMR | 0.0097 | − 0.2910 | − 0.1313 |

| ASIR | 0.7684 | 0.4964 | 0.6567 |

| MIR | − 0.7812 | − 0.7974 | − 0.9092 |

| Very high HDI | |||

| Incidence | 0.2912 | 0.1267 | 0.2594 |

| Mortality | 0.2376 | 0.1239 | 0.2470 |

| ASMR | 0.1736 | 0.1297 | 0.2491 |

| ASIR | 0.6295 | 0.4920 | 0.6815 |

| MIR | − 0.5431 | − 0.4827 | − 0.6481 |

| High HDI | |||

| Incidence | − 0.0541 | 0.1230 | − 0.0813 |

| Mortality | − 0.1054 | 0.0812 | − 0.1637 |

| ASMR | − 0.0272 | 0.2337 | 0.1470 |

| ASIR | 0.1865 | 0.3764 | 0.3815 |

| MIR | − 0.4858 | − 0.2572 | − 0.6200 |

| Medium HDI | |||

| Incidence | 0.1146 | 0.0206 | 0.1328 |

| Mortality | − 0.0069 | 0.0291 | 0.0546 |

| ASMR | 0.5255 | − 0.3623 | 0.3351 |

| ASIR | 0.6791 | − 0.2999 | 0.4842 |

| MIR | − 0.7573 | − 0.2272 | − 0.5751 |

| Low HDI | |||

| Incidence | 0.8311 | − 0.0905 | 0.2830 |

| Mortality | 0.7966 | − 0.0401 | 0.2453 |

| ASMR | 0.1511 | − 0.0879 | 0.2783 |

| ASIR | 0.3577 | − 0.0430 | 0.4405 |

| MIR | − 0.4842 | − 0.0498 | − 0.3481 |

Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio; income, gross national income (GNI) per capita; LE_male, life expectancy of males (at birth); HDI, human development index. Data pertains to low HDI (15 countries), medium HDI (18 countries), high HDI (31 countries), and very high HDI (36 countries) for the period 1990 to 2016 and is procured from Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550)

Discussion

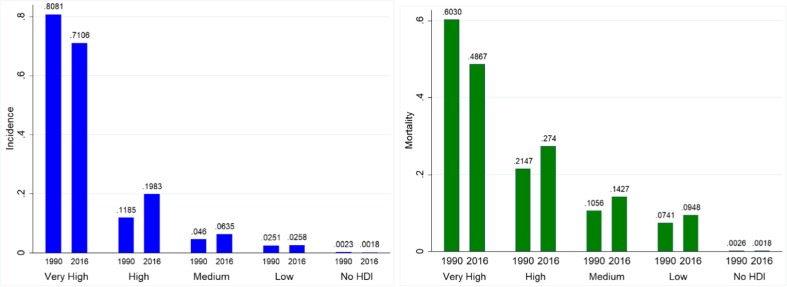

In this paper, we examined the burden of prostate cancer in 87 countries and their temporal patterns over 1990 to 2016. Using GBD 2016 data, we showed that the PCa burden increased considerably across the globe in the last three decades with wide geographical inequalities as per development levels. While incidence rates (both all-age numbers and rates) were the highest in developed countries, the mortality rates, however, were on the higher side in low-HDI countries. The developing countries now account for a significant share of incidence and mortality with the share of prostate cancer decreasing in the developed countries (high/very high HDI). Figure 4 illustrates this transition with less-developed countries (low/medium HDI) accounting for 9.9% of incident cases in 2016 versus 7.1% in 1990 and resulted in 23.8% of global cancer deaths against 18% in 1990 indicating higher incidence rates in developed countries but low survival rates in less-developed countries. The disparity between developing and developed countries becomes more noticeable in the case of mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR), a proxy indicator of a 5-year survival rate [7] than that observed in the case of incidence or mortality with the USA, for instance, recorded mortality-to-incidence ratio of 0.10 and seven of the low-HDI countries registering MIR in excess of 1 (more than a tenfold difference) in 2016.

Fig. 4.

Percentage share of HDI categories in prostate cancer burden a incidence and b mortality in 2016. Incidence, all-age incidence numbers; mortality, all-age deaths. Data pertains to low HDI (15 countries), medium HDI (18 countries), high HDI (31 countries), and very high HDI (36 countries) for the period 1990 to 2016 and is procured from Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550)

The incidence rate of prostate cancer was the highest in developed countries led by Australia with ASIR of 174.1/100,000 followed by the USA with ASIR of 172.5/100,000 in 2016. High incidence, both all-age and age-standardised in developed countries, is attributed to population ageing, increasing life spans, and screening of prostate cancer [15]. Screening using prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, in particular, has almost become a routine in developed countries and has been instrumental in detecting PCa in early stages, thereby, resulting in improved survival and reduced mortality rates [16–19]. Early screening using PSA testing or in combination with the digital rectal examination (DRE), however, is also not without limitations such as high false positive rates and overdiagnosis/overtreatment [20–22].5 Cancer therapeutics is moving away from a reactive approach to a predictive, preventative, and personalised approach where attention is given to predict cancer before its onset, diagnose early or in pre-cancerous state, and risk-stratify patients to provide personalised treatment regimens [24–26]. In this approach, overtreatment and overdiagnosis can be tackled using a multiomic approach to cancer diagnosis [27, 28]. Omics technologies comprising of genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and radiomics have wide-ranging applications in cancer detection, risk-stratification of patients, and improving the accuracy of diagnostic and prognostic procedures [28, 29]. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, for instance, has been demonstrated to have prognostic value, and the fact that it can be measured in urine makes it an ideal biomarker supplementing the PSA test [30–32]. Cheng and Zhan [27] highlighted the limited applicability of use of a single molecule as a biomarker for prediction and personalised treatment for cancer and advocated for multi-parameter strategies in PPPM. In this regard, prostate health index (phi), which combines total, free, and (-2) proPSA and approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) for PCa testing, has been demonstrated to have greater specificity in determining clinically significant prostate cancer than PSA testing alone [33–36].

A key component of PPPM is targeted therapy which seeks to offer individualised treatment options on the basis of grade and stage of the tumour along with patients’ characteristics [24–26]. Treatment paradigms for prostate cancer range between active surveillance (for indolent tumour), radiation therapy (external-beam RT, brachytherapy, etc.), surgical therapy (radical prostatectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection, etc.), and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) or a combination of these. Again, the role of PPPM becomes pertinent in this respect to provide personalised treatment out of the basket of treatment options on the basis of the stage of diagnosis, risk-category, estimated life expectancy of the patient, Gleason score,6 PSA level and velocity, and familial history of prostate cancer along with other comorbid conditions [4].

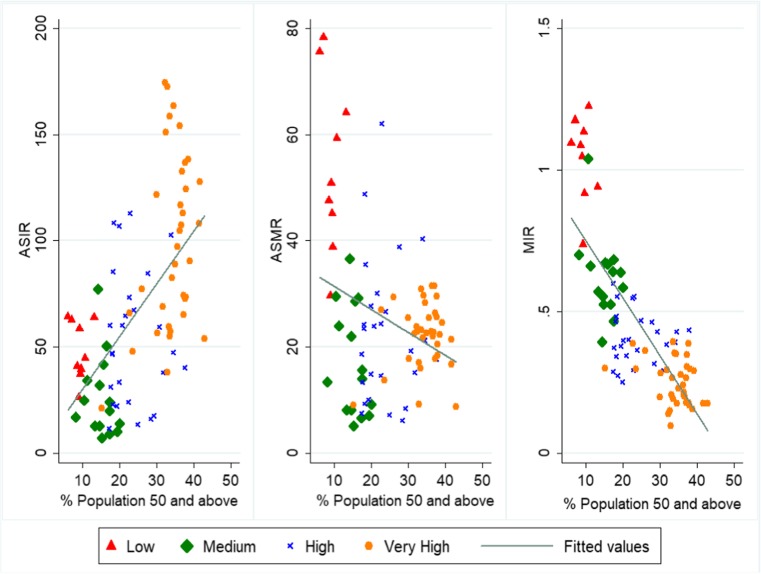

Although the aetiology of prostate carcinoma is not yet completely understood, there are a few well-established risk factors of prostate cancer such as ageing, ethnicity (African-American), family history, and behavioural and environmental risk factors [15, 37–39]. Ageing is found to be the leading risk factor of prostate cancer with incidence rates being higher in countries with a high proportion of the elderly population, whereas MIR and age-standardised mortality rate were higher in demographically younger countries with lesser developed healthcare system (Fig. 5). While HDI was positively associated with ASIR, it had a strong negative effect on MIR. The benefit of human development in developed countries is that majority of the PCa detected in these countries is in early stages whereas advanced tumour is detected in developing countries resulting in poor prognosis and survival. The proactive approach of PPPM can further help in early detection and boosting survival rates of PCa patients. A developed country, therefore, is in a relatively better position to adopt PPPM practices of prevention, offer multiomic diagnostic and prognostic approaches and thus can offer tailor-made solutions for individualised treatments.

Fig. 5.

Prostate cancer burden versus the proportion of population aged 50 years and above in 2016. ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; ASMR, age-standardised mortality rate; MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio. Data pertains to low HDI (15 countries), medium HDI (18 countries), high HDI (31 countries), and very high HDI (36 countries) for the period 1990 to 2016. Countries were categorised into four groups as per HDI value in 2015: very high (HDI > 0.800), high (0.700 < HDI < 0.799), medium (0.550 < HDI < 0.669), and low (HDI < 0.550). Data source: ASIR, ASMR data is from Global Burden of Disease 2016 study; proportion of population aged 50 years and above is from World Development Indicators (WDI) database of World Bank

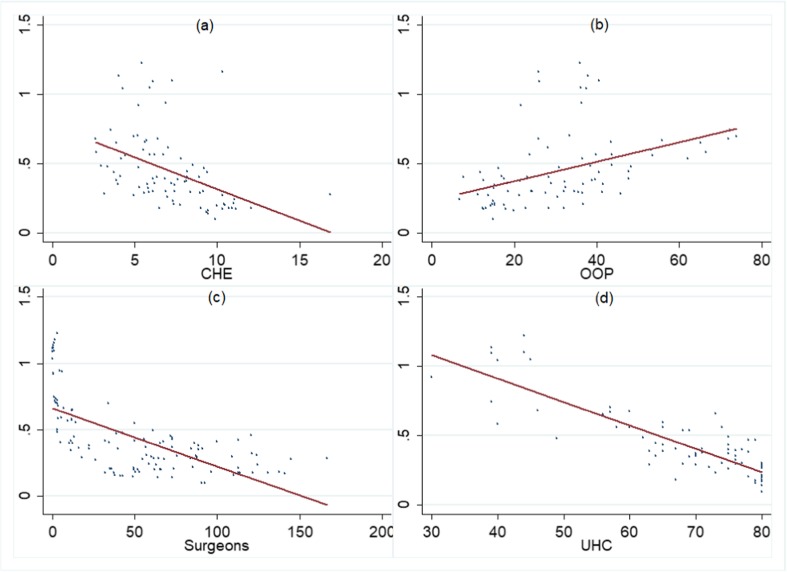

There was a high burden of prostate cancer in Africa exemplified by the highest ASMR of Zimbabwe (78.2/100,000) followed by Uganda with ASMR of 75.5/100,000 in 2016. The low survival rates in these countries were evidenced by high MIR (a proxy for survival) with many of these countries recording MIR greater than 1 in 2016. The high genetic susceptibility of prostate carcinoma in men of African origin (be it African-Americans or men in African countries), as well as high mortality and low survival rates, has been documented before [40]. There is a multitude of factors that govern such differences in the survival rates such as lack of screening, late disease presentation, limited healthcare access, and low awareness and low socioeconomic status [30]. Apart from that, there are few inherent weaknesses of the healthcare system of these countries. Figure 6 illustrates this point, showing that current health expenditures (% age of GDP) are lower, out-of-pocket expenditure (OOP) as a percentage of total health expenditure is higher, density of specialist surgeons is lower, and universal health coverage is lower in countries having high mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) which are evidently the less-developed countries.

Fig. 6.

Relation between prostate cancer mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) and country-specific healthcare parameters a MIR vs CHE, b MIR vs OOP, c MIR vs surgeon workforce, d MIR vs UHC. MIR, mortality-to-incidence ratio; CHE, current health expenditure as %age of GDP; OOP, out-of-pocket expenditure as %age of total health expenditure; surgeon workforce, number of specialist surgeons per 100,000 population; UHC, universal health coverage service index. The data corresponding to MIR, CHE, UHC, and OOP pertains to the year 2015. The data of the surgeon workforce pertains to years ranging from 2010 to 2015 depending upon country-level availability of data. All the data is procured from health nutrition and population statistics database of World Bank

Limitations

First, the estimates of prostate cancer burden were procured from the Global Burden of Disease 2016 study and the quality of estimates crucially depends upon data availability from cancer registries. As cancer registries provide incomplete coverage and lack completeness in many low-income countries, GBD employs data available spatially and temporally from neighbouring locations. Lack of cancer registry data yields wide uncertainty intervals which may be too wide to provide meaningful policy implications in these countries. Second, due to under-reporting or misclassification of cancer deaths in less-developed countries, the estimates utilised and reported here may be downward biased. Third, as is well known, cancer detected early (clinical stage 1) is less severe and life-threatening as compared to a case encountered later (stage 3 or 4), but there are no estimates of cases diagnosed in various clinical stages; therefore, we had to rely on the total number of cancer cases (irrespective of stage) to examine the burden of prostate cancer. Finally, we employed MIR as a proxy for survival rate which is not an exact measure of survival rate but a proxy of survival rate. The usefulness of MIR as a predictor of a 5-year survival rate crucially depends upon the quality of data and data completeness [32]. As this study contains estimates of many developing countries in which data from cancer registries is far from complete, therefore, MIR can only serve as a crude measure of survival rate and can only indicate the direction of relative survival in different countries.

Conclusions and expert recommendations

The burden of prostate cancer is rising globally with the incidence being higher in developed parts of the world against high mortality rate and MIR (a proxy for survival) in less-developed countries particularly African regions. Greater human development leads to early detection of malignancy, boosts awareness levels, and offers better treatment paradigms in developed countries. On the basis of past trends, the burden of PCa is expected to escalate further in the future due to a sedentary lifestyle, eating habits and obesity, etc. However, due to the lack of early detection, late disease presentation, and the lack of active surveillance systems in less-developed countries, it is expected to put pressure on the resource-constrained healthcare systems. A patient afflicted in these countries, therefore, is in a relatively disadvantageous state due to late diagnosis, access to treatment options, and a high cost of treatment which is incurred mostly from own pocket. These factors result in low survival rates and great economic hardships for a cancer patient in these countries. As few individuals are more likely to get cancer than others and cancer treatment is more costly than its prevention, the focus of medicine must shift from a reactive to a proactive one in line with PPPM principles of prevention, diagnostic, and prognostic accuracy, and offering personalised treatments rather than offering one size fits all type of solutions. In order to prevent the disease onset, risk-stratify patients, and provide personalised medicine, the capability of both healthcare system as well as patients has to be boosted. As survival rates are positively associated with the human development level of a country, the PPPM strategies are more likely to be adopted in developed countries but must be promoted in low-resource economies too, where survival rates are low.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) for making Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data pertaining to prostate cancer available in the public domain.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The research is conducted using data available in the public domain and does not include any human participants and/or animals.

Footnotes

For more details on GBD methodology, the readers are referred to the GBD 2016 disease, injuries, and risk factor study [1, 6, 12].

In this paper, we report UIs for the estimates directly available from GBD which were calculated on the basis of 1000 draws for each estimate and do not report UIs for MIR as we calculated MIR on the basis on mean estimates.

UNDP defines mean number of years of schooling as the number of years of schooling received by people ages 25 and older, and expected years of schooling is defined as number of years of schooling that a child of school entrance age can expect to receive if prevailing patterns of age-specific enrolment rates persist throughout life.

Very High HDI: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zeeland, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and USA.

High HDI: Algeria, Belarus, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Iran, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Serbia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Medium HDI: Bangladesh, Bolivia, Egypt, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Morocco, Myanmar, Pakistan, Paraguay, Philippines, South Africa, and Vietnam.

Low HDI: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Madagascar, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

No HDI category: Puerto Rico

Given high overdiagnosis and overtreatment, USPSTF in 2012 statement recommended omitting PSA screening from routine primary care for men [23].

The WHO endorsed the Gleason grading system in the 2004 classification of prostate cancer.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaborators Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2016 a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1553. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorr M, Holzel D, Schubert-Fritschle G, Engel J, Schlesinger-Raab A. Changes in prognostic and therapeutic parameters in prostate cancer from an epidemiological view over 20 years. Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38:8–14. doi: 10.1159/000371717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winter A, Sirri E, Jansen L, Wawroschek F, Kieschke J, Castro FA, Krilaviciute A, Holleczek B, Emrich K, Waldmann A, Brenner H. Comparison of prostate cancer survival in Germany and the USA: can differences be attributed to differences in stage distributions? BJU Int. 2017;119:550–559. doi: 10.1111/bju.13537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohler JL, Bahnson RR, Boston B, Busby JE, D'Amico A, Eastham JA, Enke CA, George D, Horwitz EM, Huben RP, Kantoff P, Kawachi M, Kuettel M, Lange PH, MacVicar G, Plimack ER, Pow-Sang JM, Roach M, Rohren E, Roth BJ, Shrieve DC, Smith MR, Srinivas S, Twardowski P. Prostate cancer: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinn M, Babb P. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part II: individual countries. BJU Int. 2002;90(2):174–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GBD 2016 Cause of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vostakolaei F, Karim-Kos HE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Visser O, Verbeek AL, Kiemeney LA. The validity of the mortality to incidence ratio as a proxy for site-specific cancer survival. Eur J Pub Health. 2010;21:573–577. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sunkara V, Hebert JR. The colorectal cancer mortality-to-incidence ratio as an indicator of global cancer screening and care. Cancer 2015. 2015;121(10):1563–1569. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SL, Wang SC, Ho CJ, Kao YL, Hsieh TY, Chen WJ, Chen CJ, Wu PR, Ko JL, Lee H, Sung WW. Prostate cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios are associated with cancer care disparities in 35 countries. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40003. doi: 10.1038/srep40003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma R. Breast cancer incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) are associated with human development, 1990–2016: evidence from Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Breast Cancer. 2019:1–18. 10.1007/s12282-018-00941-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (GBD 2016) results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2017. Available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (Accessed: August 14–16, 2018).

- 12.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury, Incidence and Prevalence collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foreman KJ, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Modeling causes of death: an integrated approach using CODEm. Popul Health Metrics. 2012;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Human Development Database: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data# (Accessed: 30.6.2018 and 1.7.2018).

- 15.Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford ED, Robert Grubb AB, III, Andriole GL, Jr, Chen MH, Izmirlian G, Berg CD, D'Amico AV. Comorbidity and mortality results from a randomized prostate cancer screening trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:355–361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roobol MJ, Kranse R, Bangma CH, van Leenders AG, Blijenberg BG, van Schaik RH, Kirkels WJ, Otto SJ, van der Kwast TH, de Koning HJ, Schröder FH. Screening for prostate cancer: results of the Rotterdam section of the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;64:530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Zappa M, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Määttänen L, Lilja H, Denis LJ. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnsrud RG, Holmberg E, Lilja SJ, Hugosson J. Opportunistic testing versus organized prostate-specific antigen screening: outcome after 18 years in the Göteborg randomized population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2008: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and cancer screening issues. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:161–179. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry MJ, Mulley AJ., Jr Why are a high overdiagnosis probability and a long lead time for prostate cancer screening so important? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:362–363. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Ebell M, Epling JW, Kemper AR, Krist AH. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama. 2018;19:1901–1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:120–134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grech G, Zhan X, Yoo BC, Bubnov R, Hagan S, Danesi R, Vittadini G, Desiderio DM. EPMA position paper in cancer: current overview and future perspectives. EPMA J. 2015;6:9. doi: 10.1186/s13167-015-0030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golubnitschaja O, Baban B, Boniolo G, Wang W, Bubnov R, Kapalla M, Krapfenbauer K, Mozaffari MS, Costigliola V. Medicine in the early twenty-first century: paradigm and anticipation - EPMA position paper 2016. EPMA J. 2016;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssens JP, Schuster K, Voss A. Preventive, predictive, and personalized medicine for effective and affordable cancer care. EPMA J. 2018;9:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s13167-018-0130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng T, Zhan X. Pattern recognition for predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine in cancer. EPMA J. 2017;8:51–60. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu M, Zhan X. The crucial role of multiomic approach in cancer research and clinically relevant outcomes. EPMA J. 2018;9:77–102. doi: 10.1007/s13167-018-0128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horgan RP, Kenny LC. ‘Omic’ technologies: genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics. Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;13:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomlins SA, Day JR, Lonigro RJ, Hovelson DH, Siddiqui J, Kunju LP, Dunn RL, Meyer S, Hodge P, Groskopf J, Wei JT. Urine TMPRSS2: ERG plus PCA3 for individualized prostate cancer risk assessment. Eur Urol. 2016;70:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leyten GH, Hessels D, Jannink SA, Smit FP, de Jong H, Cornel EB, de Reijke TM, Vergunst H, Kil P, Knipscheer BC, van Oort IM. Prospective multicentre evaluation of PCA3 and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions as diagnostic and prognostic urinary biomarkers for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salagierski M, Schalken JA. Molecular diagnosis of prostate cancer: PCA3 and TMPRSS2: ERG gene fusion. J Urol. 2012;187:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Sanda MG, Wei JT, Klee GG, Bangma CH, Slawin KM, Marks LS, Loeb S, Broyles DL, Shin SS. A multi-center study of [− 2] pro-prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in combination with PSA and free PSA for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0 to 10.0 ng/mL PSA range. J Urol. 2011;185:1650–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang YQ, Sun T, Zhong WD, Wu CL. Clinical performance of serum [-2] proPSA derivatives, % p2PSA and PHI, in the detection and management of prostate cancer. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2:343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeb S, Sanda MG, Broyles DL, Shin SS, Bangma CH, Wei JT, Partin AW, Klee GG, Slawin KM, Marks LS, Van Schaik RH. The prostate health index selectively identifies clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tosoian JJ, Druskin SC, Andreas D, Mullane P, Chappidi M, Joo S, Ghabili K, Agostino J, Macura KJ, Carter HB, Schaeffer EM. Use of the Prostate Health Index for detection of prostate cancer: results from a large academic practice. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:228–233. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer–analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, Czene K, Havelick DJ, Scheike T, Graff RE, Holst K, Möller S, Unger RH, McIntosh C. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in Nordic countries. Jama. 2016;315:68–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGinley KF, Tay KJ, Moul JW. Prostate cancer in men of African origin. 2016 Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:99–107. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkin DM, Bray F. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods part II. Completeness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]