Abstract

Optimal lysosome function requires maintenance of an acidic pH maintained by proton pumps in combination with a counterion transporter such as the Cl−/H+ exchanger, CLCN7 (ClC-7), encoded by CLCN7. The role of ClC-7 in maintaining lysosomal pH has been controversial. In this paper, we performed clinical and genetic evaluations of two children of different ethnicities. Both children had delayed myelination and development, organomegaly, and hypopigmentation, but neither had osteopetrosis. Whole-exome and -genome sequencing revealed a de novo c.2144A>G variant in CLCN7 in both affected children. This p.Tyr715Cys variant, located in the C-terminal domain of ClC-7, resulted in increased outward currents when it was heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Fibroblasts from probands displayed a lysosomal pH approximately 0.2 units lower than that of control cells, and treatment with chloroquine normalized the pH. Primary fibroblasts from both probands also exhibited markedly enlarged intracellular vacuoles; this finding was recapitulated by the overexpression of human p.Tyr715Cys CLCN7 in control fibroblasts, reflecting the dominant, gain-of-function nature of the variant. A mouse harboring the knock-in Clcn7 variant exhibited hypopigmentation, hepatomegaly resulting from abnormal storage, and enlarged vacuoles in cultured fibroblasts. Our results show that p.Tyr715Cys is a gain-of-function CLCN7 variant associated with developmental delay, organomegaly, and hypopigmentation resulting from lysosomal hyperacidity, abnormal storage, and enlarged intracellular vacuoles. Our data supports the hypothesis that the ClC-7 antiporter plays a critical role in maintaining lysosomal pH.

Keywords: lysosomal pH, lysosomal storage disease, oculocutaneous albinism, chloroquine, ClC-7 antiporter, lysosomal hyperacidity, lysosomal membrane counterion, cutaneous albinism

Introduction

Lysosomes are cellular organelles whose enzymes degrade macromolecules whose enzymes contribute to the salvage of small molecules by degrading macromolecules. For optimal function, lysosomes rely on the maintenance of an acidic luminal pH;1 the active accumulation of protons is driven primarily by V-ATPase, but luminal acidification also requires a neutralizing ion movement.2, 3 Defects in these ion channels or transporters can lead to physiological disruptions including neurodegeneration and lysosomal-storage diseases.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Chloride has been proposed to provide this counterion in the lysosomal membrane10 through the transporter CLCN7 (ClC-7), which is encoded by CLCN7 (MIM: 602727), but its role in lysosomal acidification has been controversial.5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13

Individuals with loss-of-function CLCN7 variants develop autosomal-dominant osteopetrosis-2 (OPTA2; MIM: 166600) and autosomal-recessive osteopetrosis 4 (OPTB4; MIM: 611490). Herein we describe two unrelated children who have an identical pathogenic de novo variant in CLCN7 without osteopetrosis but instead show a pleiotropic syndrome, including cutaneous albinism, developmental delay, organomegaly and enteropathy, lysosomal storage, and cellular accumulation of large intracellular vacuoles. The variant, c.2144A>G (p.Tyr715Cys) (GenBank: NM_001287.5) (ClinVar: RCV000412760.1), increases ClC-7-mediated chloride flux, decreases lysosomal pH, and increases the size and number of intracellular vacuoles in the fibroblasts from probands. Mice harboring an equivalent heterozygous variant also exhibited hypopigmentation, organomegaly, and lysosomal storage, further supporting the conclusion that the p.Tyr715Cys variant is pathogenic. Additionally, the cellular hyperacidity and cellular phenotype in probands’ cells were rescued in vitro by treatment with the alkalinizing agent chloroquine, emphasizing the role of ClC-7 in regulating lysosomal pH.

Material and Methods

Subjects

Proband 1 was enrolled in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Undiagnosed Diseases Network14, 15 under clinical protocol 15-HG-0130, “Clinical and Genetic Evaluation of Patients with Undiagnosed Disorders Through the Undiagnosed Diseases Network,” approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Institutional Review Board. Proband 2 was referred to the Department of Medical Genetics and Genomic Medicine at Saint Peter’s University Hospital, New Brunswick, NJ. For both children, written informed consent was obtained from the parents for clinical and research testing.

Genetic Analysis

For proband 1 and her family, genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood through the use of the Gentra Puregene Blood Kit (QIAGEN). For both probands, clinical whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed by GeneDx. Whole-genome sequencing was done at HudsonAlpha. Sanger dideoxy sequencing was performed by Macrogen; primers are listed in Table S3. The sequences were analyzed with Sequencher v.5.0.1 (GeneCodes).

Tissue and Cell Studies

Standard procedures for light and electron microscopy are described in the Supplemental Data. Primary dermal fibroblasts were cultured from forearm skin punch biopsies as described.16

For LysoTracker studies, cultured fibroblasts were plated at 6,000 cells/well into 96-well microplates and incubated with 83.3nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L7528) at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were then fixed in 100 μl/well 3.2% paraformaldehyde solution containing 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, H1399) in PBS and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Plates were imaged on an INCell Analyzer 2200 (GE Healthcare) with the DAPI, Texas Red, and bright-field channels, and the intensity of LysoTracker per cell was measured. Fibroblasts from probands were compared to one positive control (NPC-25 fibroblasts) and three negative control cell lines (Coriell GM23972A; ATCC PCS201-012; ATCC PCS201-010).

For immunofluorescence, primary dermal fibroblasts were cultured from forearm skin punch biopsies as described.16 Coriell GM23972A, ATCC PCS-201-012, and ATCC PCS-201-010 WT fibroblast cell lines were used as controls. For high-magnification morphology assays, at least 10,000 cells were seeded overnight in chamber slides (LabTek), washed with PBS, and fixed with 3.8% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated for 2 h with blocking solution (4% BSA, 1% donkey serum, and 1% saponin). Cells were then incubated with the primary antibody Lamp1 (mouse, DSHB H4A3) for lysosomes. The next day, the cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (488 Alexa Fluor fluorescent secondary antibody, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and/or Phalloidin (555 Phalloidin, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for actin fibers, and slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting media with DAPI (Vectorlabs) and imaged with an LSM 880 confocal scanning microscope (Zeiss) with a 63× oil immersion lens.

For fibroblast transfections, a pCMV6 plasmid containing human CLCN7 cDNA (RC203450, Origene) was mutagenized so that p.Tyr715Cys was introduced. Transfections were performed with the Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primary antibodies were used: Lamp1 (mouse, DSHB H4A3) and anti-Myc antibody (OriGene).

To measure lysosomal pH, we incubated cells overnight with 3.5 mg/mL Oregon green 488 10,000 MW dextran (ThermoFisher Scientific D7170) and followed this by a 4-h dye-free chase. Excitation ratio image pairs were obtained with a Zeiss widefield microscope a excitation wavelengths of 440/490 nm and emission at 534 nm.17 Ratios were converted to pH by calibration in a series of buffers (pH 4.0–7.0) in the presence of ionophores so that pH was equilibrated across all membranes. We averaged individual lysosomal ratios to determine a mean lysosomal pH for each analyzed cell.

For colocalization of LAMP1 and cathepsin B, fibroblast cells were treated with Magic Red substrate (ImmunoChemistry Technologies) which stains cathepsin B, a marker for functional lysosomes, for 30 min at 37°C, rinsed briefly with PBS, and fixed with 3% PFA, followed by the staining with LAMP1.

For DNA extraction from fibroblasts of proband 2, cells were pelleted, and the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In Vitro Chloroquine Studies

For chloroquine treatment, ATCC control and fibroblasts from probands were plated in Greiner Bio-One optical 96-well plates (Grenier Bio-One Ref #655090) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Media were supplemented with 50–300 nM (for pH measurements) or 50–600 nM (for measurement of vacuole size) chloroquine diphosphate salt (Sigma C6628), and plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h (pH measurement) or 24 h (vacuole imaging). For imaging vacuole size, cells were fixed with 3.2% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences #15710), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma X100) and stained with High Content Screening CellMask Red Stain (Life Technologies H32712). Cells were washed with 1× Dulbeco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline and imaged on a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope with a 63× oil immersion lens. Scale bars represent 30 μM.

Expression Constructs for Electrophysiology

c-Myc-tagged ClC-7PM and c-Myc-tagged OSTM1 constructs (RC203450 and RC209871, respectively, from OriGene. ClC-7PM carries the surface-targeting variants L23A/L24A/L68A/L69A; this construct is referred to as wild-type [WT] for comparison with the variant identified in the probands below.) were subcloned into pGEM-HE2 vector for heterologous expression in xenopus laevis oocytes.18 The c.2144A>C (p.Tyr715Cys) missense variant was introduced using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing of the complete open reading frame.

Voltage-Clamp Xenopus Laevis Oocytes

Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with cRNA coding for WT or p.Tyr715Cys ClC-7PM and for OSTM1 (23 ng for Myc-tagged ClC-7 constructs and an additional 23 ng for Myc-tagged Ostm1) that was transcribed with the mMessage Machine kit (Ambion). After incubating the oocytes for 5 days at 17°C, we measured currents through the use of standard two-electrode voltage clamp techniques (OC-725C; Warner Instruments) at room temperature. Experiments were performed in ND96 buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1.8 mM CaCl2 at pH 7.6 with NaOH). Data were filtered at 1–3 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz using pClamp software (Molecular Devices). Microelectrode resistances were 0.1–0.5 MΩ when filled with 3M KCl.

Murine Model

We employed CRISPR/Cas9 technology19 to create a knock-in allele in murine Clcn7 to mimic the human c.2144 A>G (p.Tyr715Cys) variant. Pronuclear co-injection of an oligonucleotide donor, an sGRNA specific for the locus of interest, and a WTCas9mRNA were performed. The sgRNA, 5′-GGAAGCGTGGATAGGCATCT (CGG)-3′, was designed with CRISPRScan3 and directs Cas9 to introduce a double-strand break approximately six bases upstream of the missense site. To generate this guide, we annealed the oligonucleotide, “Clcn7 gRNA2,” which includes the T7 promoter and guide sequence (the polynucleotide stretch at the 5′ terminus of the oligo mitigates spontaneous loss of nucleotides) to the universal sgRNA oligonucleotide, “gRNAUniv4,” and extended the two by using the QuikChange Lightning proofreading polymerase (Agilent) and the following cycling parameters: 98°C for 2 min, 55°C for 10 min, and 72°C for 10 min (oligonucleotides at 0.4 μM each). The double-stranded product was then transcribed in vitro with the T7 HiScribe RNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs), as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Input DNA was removed with TURBODNase (ThermoFisher). sgRNA was purified and concentrated with the RNA Clean and Concentrate 5 Kit (Zymo Research). The size and integrity of the sgRNA were confirmed on a 1.5% agarose gel.

5′-AGCGGCGACTGAGGCTGAAGGACTTCCGAGATGCCTGTCCACGCTTCCCCCCAATCCAGTCCATTGATGTATCCCAGGATG-3′ (Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT]) was used as the donor oligonucleotide (mutant base underscored) and was synthesized as a custom RNA–DNA oligonucleotide with standard desalting (IDT). Pronuclear injection was performed with standard procedures. In brief, fertilized eggs were collected from superovulated C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories; abbreviated B6) females approximately 9 h after they mated with C57BL/6J males. Microinjections were performed with a capillary needle with a 1–2 μm opening pulled with a Sutter P-1000 micropipette puller as described.20 Injected eggs were surgically transferred to pseudopregnant CB6F1 hybrid recipient females and bred from a cross of Balb/cJ females with C57BL/6J males.

All animal procedures were performed in a pathogen-free, Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) approved facility in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the NHGRI Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) under the Animal Study Program G-14-3 (Mouse Models for Disorders of the Lysosomes and Lysosome-Related Organelles). Genotyping was performed on founder animals and progenies via Sanger sequencing of DNA extracted from tails through use of the Extract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification of the region of interest was carried out by PCR with the following primers: 5′-CTTAGAGGTGACCGTGGAATAGCAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGTACTGAGCTGTCTCTTCCCCTCCAT−3′. Cycling parameters were as follows: 95°C for 3 min, 40 cycles of (95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min), and 72°C for 7 min. Reactions were treated with ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher) and directly sequenced with one or the other of the primers above. PCR product from missense-positive DNA was cloned into PCR4-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Founder mice were outbred to C57BL/6J. The resultant mice were very sickly, and most died at 4–5 weeks of age; the surviving mice were viable until 18–20 weeks of age but were not fertile. For subsequent generation of mice, male Clcn7Y713C/+ were used as sperm donors for in vitro fertilization.

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization of 4–5 μm sections, the slides were subjected to a series of rehydration steps. Slides were stained with Periodic acid-Schiff staining for liver tissue, and tibiae were stained with von Kossa. Samples for electron microscopy were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and embedded in Epon Resin and processed as described.21

Statistical Methods

For quantification of LysoTracker intensities, 20 images were captured per well and at least four wells per cell line or treatment condition were included. INCell Analyzer (GE Healthcare) software was used for identification of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and organellar areas of cells and measurement of the integrated intensity (IxA, Organelle-Cytoplasm) in the FITC or Texas Red channel throughout the cytoplasm area, which was representative of the total integrated intensity of the lysosomal markers of interest. Prism 7 (GraphPad) was used for generation of mean + SEM plots. Statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA (and nonparametric) with Kruskal-Wallis tests and with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Presented graphs show representative data for experiments that were repeated multiple times with comparable results.

Results

A De Novo CLCN7 Variant Identified in Children with Cutaneous Albinism, Developmental Delay, and Lysosomal Storage

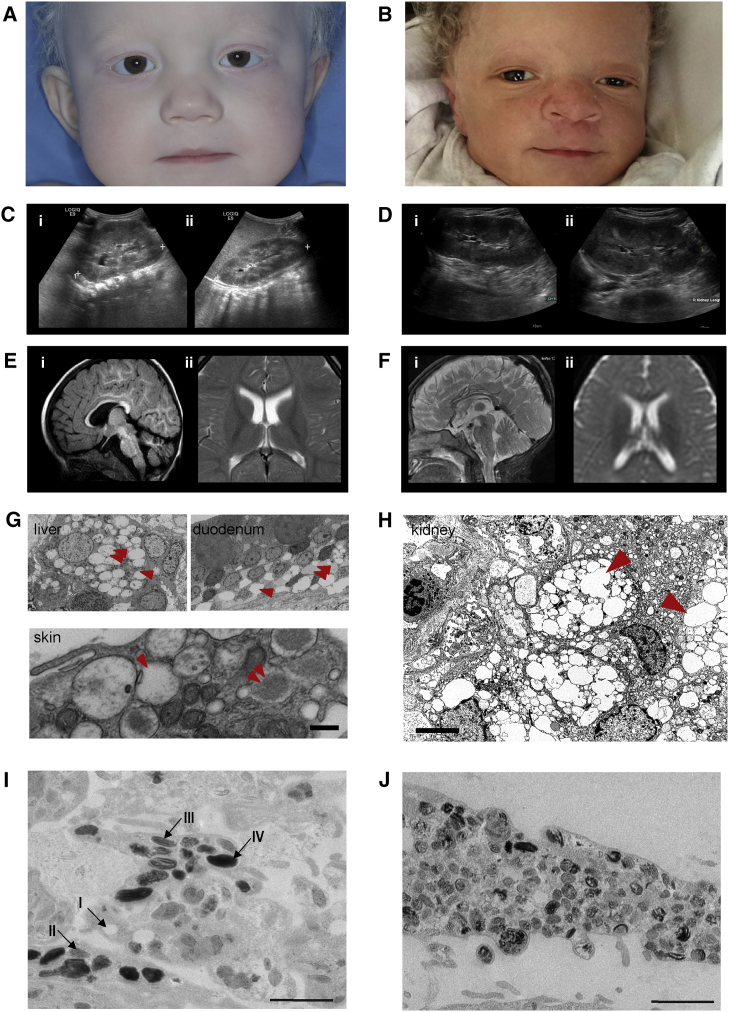

Two unrelated children, one a 22-month-old Caucasian female (proband 1) and the other a 14-month-old Ghanaian male (proband 2), presented with skin and hair hypopigmentation but normally pigmented irides (Figures 1A and 1B). Growth and development were delayed, and both probands exhibited organomegaly. Proband 1 had an enlarged liver and spleen, increased liver echogenicity compatible with steatosis or glycogen storage, and poor corticomedullary differentiation in the kidneys (Figure 1C). Proband 2 had an echogenic liver at 8 months of age and hepatomegaly by 12 months; the kidneys had doubled in size and showed poor corticomedullary differentiation (Figure 1D). Both probands exhibited delayed myelination on brain MRI (Figures 1E and 1F); neither had dysostosis multiplex or osteopetrosis.

Figure 1.

Clinical and Histological Features of Probands

(A) Proband 1 has hypopigmented skin and hair but normally pigmented irides.

(B) Proband 2, with hypopigmentation of skin and hair compared with those of his African parents. Also note the normally pigmented irides.

(C and D) Abdominal ultrasound of proband 1 (C); the left (i) and right (ii) kidneys are enlarged to more than 10 cm in length. Abdominal ultrasound of proband 2 (D); the left (i) and right (ii) kidneys are enlarged to more than 10 cm in length. For comparison, please see normal images in Figure S1B.

(E and F) Brain MRIs of proband 1 (E) at 20 months and proband 2 (F) at 12 months. Both MRIs show delayed myelination, a thin posterior corpus callosum, hyperintensity of the subthalamic nuclei, and cerebellar atrophy. Proband 1 had a thin posterior corpus callosum, hyperintensity of the brainstem, particularly in the subthalamic nuclei, and atrophy of the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres. Proband 2 had prominent subarachnoid spaces and abnormal signal intensity in the cerebral peduncles, pons, and brainstem, but no leukodystrophy. Please refer to Figure S1 and to the studies of Sanchez et al.35 for MRI images in control individuals.

(G) Transmission electron micrographs from proband 1 show abnormal cytoplasmic inclusions (arrowhead) sometimes containing amorphous floccular storage material (double arrowhead) in the macrophages of the liver and histiocytes of the duodenum. These findings are characteristic of those seen in lysosomal-storage disorders. Similar cytoplasmic inclusions were found in the skin of proband 1. The scale bar represents 1 μm.

(H) Transmission electron micrograph showing storage in the kidney of proband 2. There are numerous interstitial macrophages containing abundant cytoplasmic inclusions (arrowhead), highly suggestive of a lysosomal-storage disorder. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

(I) Transmission electron microscopy of control melanocytes isolated from a skin punch biopsy. Melanosomes mature from stage I through stage IV as they acquire homogeneous melanin pigment. The scale bar represents 1,000 nm.

(J) Transmission electron microscopy of melanocytes derived from the proband 1. Very few stage IV melanosomes are present; most are stage II. Also note that the unusual non-homogeneous distribution of pigment in the melanosomesgives a “chunky” appearance. The scale bar represents 1,000 nm.

Both children were born prematurely; on prenatal ultrasound, proband 1 had intrauterine growth retardation, and proband 2 had shortened long bones, prefrontal edema, and polyhydramnios. The cytoplasmic inclusions of proband 1 contained amorphous floccular material suggestive of storage (Figure 1G). For proband 2, a renal biopsy revealed marked distention of the medullary interstitium by lipid-laden macrophages; electron microscopy showed lipid inclusions in mesangial cells, medial myocytes, and some tubular epithelial cells; there were rare inclusions in podocytes and endothelial cells of small arteries (Figure 1H).

Some features were present in only one of the probands. Proband 1 had decreased muscle mass in the lower extremities, a limited range of motion in the ankles, diffuse hypermobility of the upper extremities, and generalized hypotonia. Proband 2 had sustained clonus and myoclonic jerks involving the lower extremities. On ophthalmic examination, proband 1 had the equivalent of a visual acuity of 20/600, and a sedated electroretinogram consistent with an early rod-cone dystrophy. Proband 2 had an unremarkable ophthalmological exam at 6 weeks of age. Proband 1 had a profound hearing loss at 2,000 Hz and 4,000 Hz in the right ear, and a neurodiagnostic auditory brain response was effectively absent. Proband 2 had posterior auricular papules, epicanthal folds, hypertelorism, thickened gingivae, a short sternum, single palmar creases, nevi, and café-au-lait macules.

Biopsies showed that both probands had cytoplasmic inclusions: in the liver, duodenum, and skin of proband 1 (Figure 1G) and in the kidney of proband 2 (Figure 1H). Compared with normal cultured melanocytes (Figure 1I), the melanocytes of proband 1 had less mature and more disorganized melanosomes (Figure 1J). Table S1 compares the general clinical features in both probands.

On exome sequencing, each proband had an identical de novo heterozygous variant in CLCN7 (c.2144A>G [p.Tyr715Cys], GenBank: NM_001287.5) (Figure S2A), a member of the CLC gene family of Cl− channels and Cl−/H+ exchangers22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27. Inactivating variants in CLCN728 and its β-subunit OSTM129 causes osteopetrosis and neurodegeneration (Figure S2B); missense variants of CLCN7 can also lead to milder forms of osteopetrosis, known as Albers-Schonberg Disease (MIM: 166600).30 No gain-of-function CLCN7 variant has been reported. The p.Tyr715Cys variant involves a highly conserved amino acid within the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of ClC-7 (Figure S2C); in silico analyses predict it to be pathogenic, and it is not present in ExAC, gnomAD, ESP, or EVS databases (see Web Resources).

The p.Tyr715Cys ClC-7 Increases Chloride Transport Current in Xenopus Oocytes and Reduces Lysosomal pH

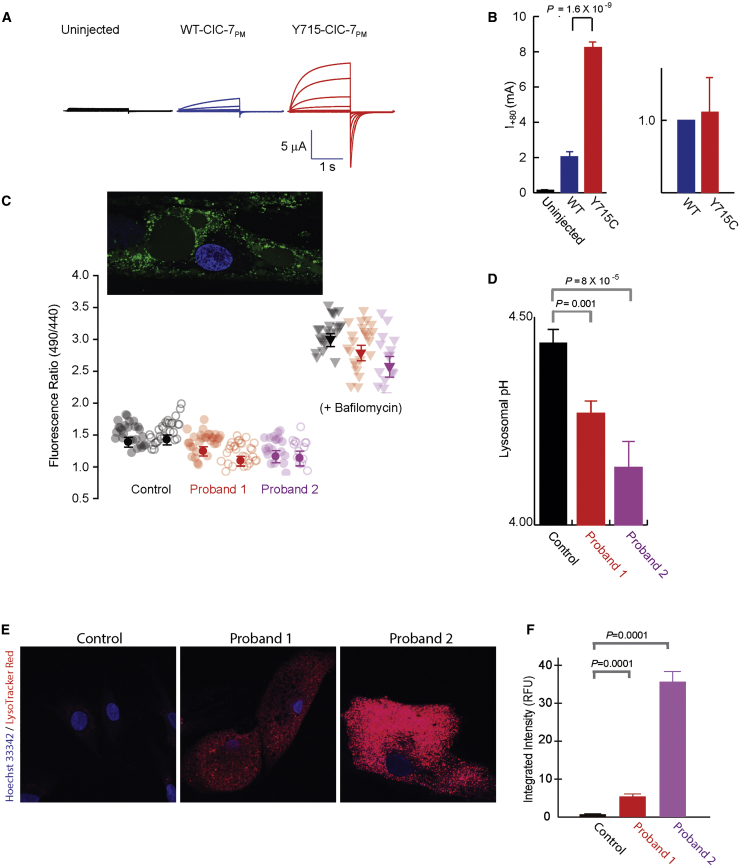

To investigate chloride transport, we expressed plasma-membrane-targeted human full-length or P.Tyr715Cys CLCN7 (along with the gene encoding its β-subunit Ostm1) in Xenopus oocytes and measured transporter current.31 The p.Tyr715Cys variant caused approximately 3-fold increases in outward currents (Figure 2A), although surface expression remained the same (Figure 2B). Despite kinetic changes, the 2:1 Cl-/H+ stoichiometry of the WT transporter was unchanged in the mutant protein (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Cellular pH and Chloride Transport Studies

(A) ClC-7 p.Tyr715Cys expression causes increased current in Xenopus oocytes. Two-electrode voltage-clamp current traces are shown for uninjected (black), WT ClC-7PM (blue), and p.Tyr715Cys ClC-7PM (red) in response to a series of 1 s voltage steps from −100 mV to + 80 mV in increments of 20 mV, followed by a step to −80 mV for 1.4 s before return to a holding potential of −30 mV.

(B) Bar graphs of current (+/− SEM, measured at +80 mV) or surface expression of uninjected (black), WT ClC-7PM, or p.Tyr715Cys ClC-7PM. For current measurements, n = 3 (uninjected), 8 (WT), or 6 (p.Tyr715Cys) from a single batch of oocytes; the experiment was reproduced 11 times in separate oocyte batches with essentially identical results. For surface expression, five separate surface biotinylation experiments were performed (with 20 each of WT and p.Tyr715Cys oocytes); intensities were normalized by the WT band intensity and averaged. The currents shown in (A) were from one of the same batches of oocytes used for the surface-expression experiments.

(C) Lysosomal pH in control and proband fibroblasts was measured with OG488 ratiometric imaging. Raw fluorescence ratios are shown for individual cells (pale circles) and averages (+/− SEM) of n = ∼50 cells (dark circles) from two independent experiments each on control neonatal fibroblasts (1.54 ± 0.1) or primary fibroblasts from either proband (proband 1, 1.30 ± 0.07; proband 2, 1.28 ± 0.08). Ratios from bafilomycin-treated cells from each are also shown as a negative control. The lower the 490/440nm fluorescence ratio, the lower the pH. An image of an OG488-treated proband cell is shown in the inset.

(D) Averaged lysosomal pH obtained from the experiments shown in part (C) (control, 4.44 ± 0.03; proband 1, 4.26 ± 0.03; proband 2, 4.19 ± 0.06). Separate calibrations were performed for each experiment and used for converting the ratios to pH values (Figure S3). Error bars indicate SEM; p values as shown.

(E) Cultured fibroblasts incubated with LysoTracker Red DND-99. Fluorescent intensity was significantly greater in cells of probands 1 and 2 than in control cells. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue channel).

(F) Mean (+/− SEM) integrated intensity of LysoTracker Red DND-99 (red channel) per cell is plotted in relative fluorescence units (RFU); values are 107. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue channel). Fluorescent intensity was significantly greater in cells of probands 1 and 2 than in control cells.

Abbreviations are as follows: SEM, standard error the mean; WT, wild-type.

If Cl− transport through ClC-7 is important for acidification, then the increased current, reflecting a gain of ClC-7 function, might be predicted to allow increased hydrogen ion transport into lysosomes. Indeed, quantitative pH measurements, as indicated by the lysosome-specific dye Oregon Green 488-dextran (OG488), revealed a pH reduction of 0.16 ± 0.06 and 0.24 ± 0.09 units in the cells of probands 1 and 2, respectively (Figures 2C and 2D; Figure S3). Increased staining with the acidotropic dye, LysoTracker Red, was also consistent with lowered lysosomal pH in the probands’ fibroblasts (Figures 2E and 2F).

Altered Lysosomal pH Leads to Vacuolar Formation in Fibroblasts

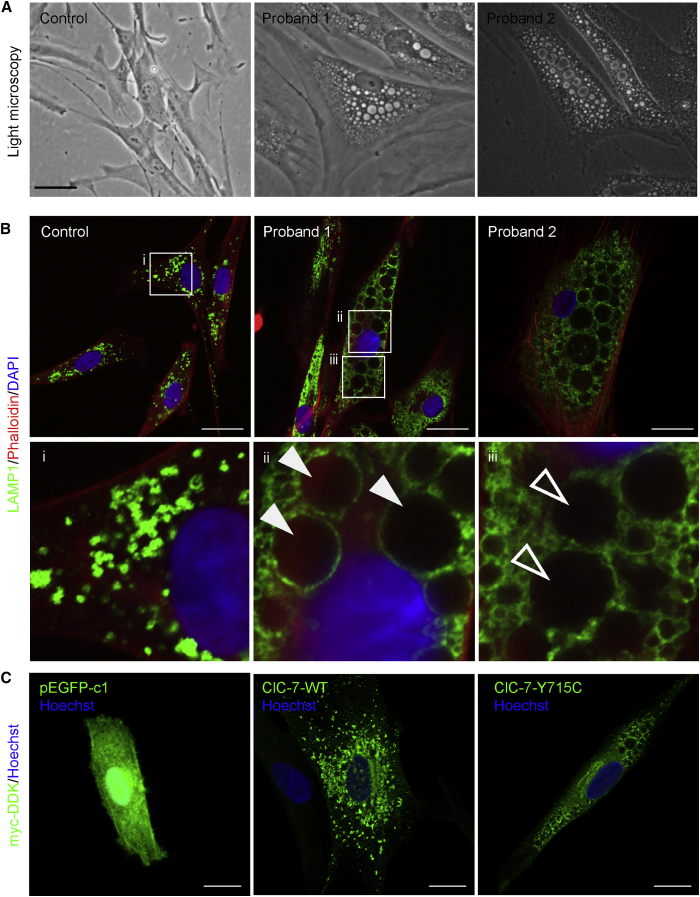

Both probands’ cultured fibroblasts contained large but variously sized cytoplasmic, single- and double-membrane vacuoles (Figure 3A), sometimes containing amorphous material and cellular debris (Figure S4A). Two pH-sensing reagents with different routes of delivery (endocytosis for OG488-dextran, membrane permeability for LysoTracker) did not stain the large vacuoles, indicating that the vacuoles are not in rapid communication with the lysosomal compartment and are not acidic. Some of the large vacuoles stained partially with Lamp1 and Rab7 (Figure 3B, Figure S4B), suggesting that they have endolysosomal properties, but most did not appear to be functional lysosomes as measured by an assay for cathepsin B activity (Figure S4C).

Figure 3.

Cellular Phenotype and Lysosomal Staining

(A) Representative bright-field images of control, proband 1, and proband 2 primary cultured fibroblasts, with large cytoplasmic inclusions in probands’ fibroblasts. The scale bar represents 100 μm.

(B) Lamp1 staining highlights the endolysosomal character of the vacuolar structures in proband 1 and 2 fibroblasts compared to WT control, in which distinct punctate lysosomes can be identified. Lamp-1 staining surrounds some part of the vacuoles of the mutant cells. Phalloidin stains actin; DAPI stains the nucleus. i, magnified image of control Lamp1 staining; ii and iii, magnified Lamp 1 staining of cells from proband 1. In WT cells, distinct lysosomes can be identified. In proband 1, some vacuoles are clearly decorated with Lamp1 (closed arrows), whereas others have less defined membranes (open arrows). The scale bar represents 25 μm.

(C) Overexpression of human CLCN7 (ClC-7) p.Tyr715Cys in fibroblasts recapitulates the cellular phenotype of cells from probands. pEGFP1-c1 transfection, which does not contain ClC-7, in control fibroblasts is shown to show efficiency of transfection. GFP protein expression was detected via a 488 channel. Control fibroblasts overexpressing a Myc-DDK-tagged ClC-7–WT allele exhibited a mottled staining pattern. Fibroblasts overexpressing Myc-DDK-tagged ClC-7 p.Tyr715Cys displayed distinct, enlarged vacuoles, like those seen in in ClC-7 p.Tyr715Cys proband fibroblasts. Protein expression in both the WT and p.Tyr715Cys cells were detected with a Myc antibody. Hoechst stains the nucleus. The scale bar represents 25 μm.

WT indicates wild-type, referring to cells overexpressing the full-length human CLCN7 (ClC-7).

To determine whether the p.Tyr715Cys variant is pathogenic, we overexpressed the variant human CLCN7 (carrying a Myc/DDK tag) in control human fibroblasts. These cells dramatically recapitulated the mutant phenotype of enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles, as opposed to findings for cells overexpressing WT CLCN7 (Figure 3C).

Mice Harboring an Orthologous Variant to p.Tyr715Cys Develop Albinism and Lysosomal-Storage Disease

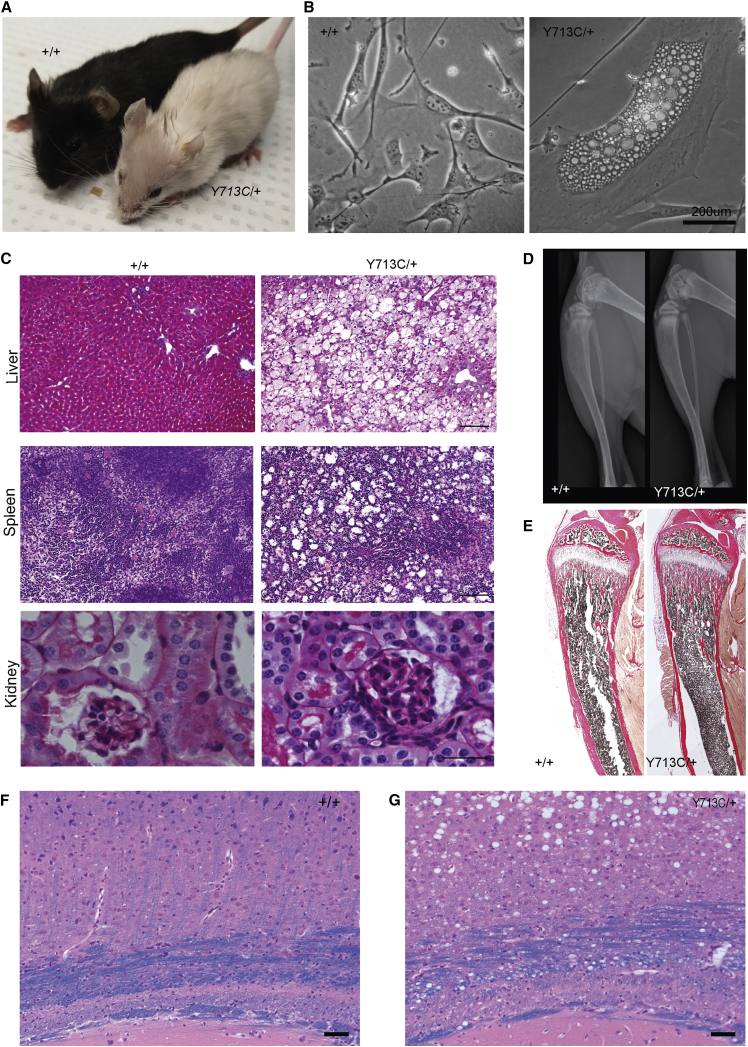

The pathogenicity of the p.Tyr715Cys variant is furthermore supported by a p.Tyr713Cys (Tyr713 is the Tyr715-equivalent amino acid in M. musculus) heterozygous knock-in mouse. The mutant mice were viable but were not fertile and did not survive past 16–18 weeks; they manifested findings like those from the probands, including striking hair hypopigmentation (Figure 4A); dermal fibroblasts with enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 4B); lysosomal storage with intracellular vacuoles in the liver, spleen, and kidneys (Figure 4C); lack of osteopetrosis (Figures 4F and 4E); brain myelination abnormalities (Figures 4F and 4G), and enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles in dermal fibroblasts that partially stained for Lamp1 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Mouse Model of Clcn7 p.Tyr713Cys

(A) Injection of a single-guide RNA targeting exon 23 of Clcn7 in mice generated the variant of interest. p.Tyr715Cys in humans corresponds to p.Tyr713Cys in mice (amino acid Tyr715 is highly conserved in several species up to C. elegans). F1 mice resulting from the injection, containing the heterozygous knock-in variant in C57/B6J background, reveal marked pigmentation defects, including white fur. Also shown is a WT mouse that is from the same C57/B6J background and has normal black fur.

(B) Periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) staining of paraffin-embedded slides of liver, spleen, and kidney tissue from WT and Clcn7Y713C/+ mice, showing increased vacuolar structures in the Clcn7Y713C/+ mouse, indicating lysosomal storage. The scale bar represents 50μm.

(C) Characterization of dermal fibroblasts. Bright-field pictures of cultured mouse fibroblasts from WT (left, +/+) and mutant (right, Y713C/+) mice. The knock-in mouse fibroblasts contain enlarged vacuoles, resembling the p.Tyr715Cys human fibroblasts.

(D) X-rays of WT and knock-in Clcn7Y713C/+ mice at 5 weeks of age, showing normal skeletal and craniofacial bones in both mice. Long bones of Clcn7Y713C/+ mouse show no evidence of osteopetrosis.

(E) Tibiae from WT and Clcn7Y713C/+ mice stained with von Kossa. These sections reveal no osteopetrosis, an intact marrow cavity, and normally organized trabecular and cortical structure in both WT and mutant mice.

(F and G) Luxol fast blue-hematoxylin-eosin stain of the brains from control (+/+) (F) and Clcn7Y713C/+ (Y713C/+) (G) mice. The blue color represents myelin formation in the corpus callosum. In Clcn7Y713C/+mice, note the presence of vacuoles in the substance of the midbrain, disrupting the organization of the corpus callosum and parts of brain white matter. The scale bar represents 50μm.

Y713C/+ refers to Clcn7Y713C/+, a mouse heterozygous for the knock-in allele; +/+ refers to a WT mouse with the same background.

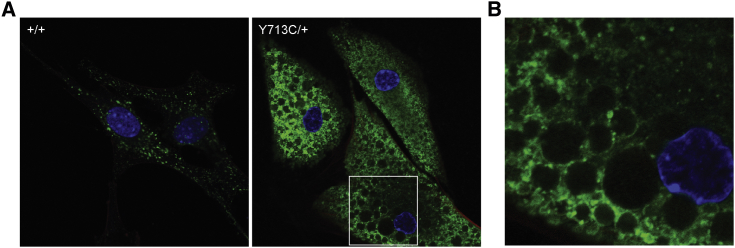

Figure 5.

Dermal Fibroblasts from Clcn7Y713C/+ Mice Exhibit Enlarged Vacuoles Partially Stained with a Lysosomal Marker

(A) Immunostaining of dermal fibroblasts isolated from WT (left, +/+) and Clcn7Y713C/+ (right, Y713C/+) mice. Lamp1 (green) decorates the outline of the vacuoles, similarly to what is seen in probands’ cells. The scale bar represents 5 μm. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue).

(B) Magnified image of mutant (Y713C/+) cells showing that the vacuoles are surrounded by LAMP1 staining.

Y713C/+ refers to Clcn7Y713C/+, a mouse heterozygous for the knock-in allele; +/+ refers to a WT mouse with the same background.

The Reduced Lysosomal pH Due to p.Tyr715Cys Is Reversed by an Alkalinizing Drug, Chloroquine

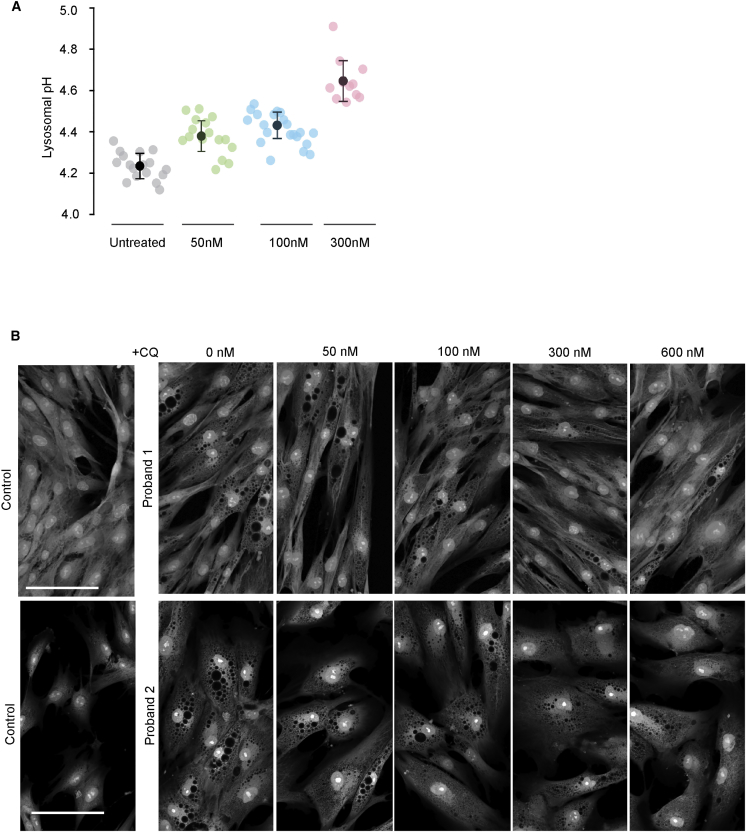

To further investigate whether cellular vacuolar phenotype is secondary to altered lysosomal pH, we incubated dermal fibroblasts from our probands and unaffected controls with the alkalinizing agent chloroquine. Chloroquine treatment increased lysosomal pH in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 6A) and reduced the abundance of large vacuoles in the mutant cells (Figure 6B), showing that reversing the ClC-7-mediated pH change could improve other aspects of the cellular defect.

Figure 6.

Effects of Chloroquine Treatment on pH and Vacuole Size in CLCN7 p.Tyr715Cys Fibroblasts

(A) Dose-dependent changes in pH of proband lysosomes treated with varying doses of chloroquine, as shown. For each drug concentration, pale symbols reflect average lysosomal pH for individual cells, and dark symbols show average pH over the entire cell population (error bars indicate ± SEM). p values: for untreated versus 50 nM, 0.0000145; for untreated versus 100 nM, 0.00000000123; for untreated versus 300 nM, 0.00000000173.

(B) Representative images of proband 1 and proband 2 fibroblasts treated for 24 hours with media supplemented (at indicated concentrations) with chloroquine, then fixed and treated with CellMask Red HCA so that the cytoplasm would be stained and changes in the vacuolar composition of these cells would be highlighted. Scale bars represent 30 μM.

Discussion

Several lines of evidence indicate that the disease of our probands resulted from a single nucleotide variant in CLCN7. First, extremely similar clinical findings were manifest in the two children of vastly different ethnicities (Table S1) and had no credible alternative genetic cause. Second, the reduced intralysosomal pH (Figures 2C and 2D) and the intracellular storage material in the probands’ cells (Figures 1I and 1J) are reasonable consequences of increased acidification due to enhanced ClC-7 activity. Third, overexpression of the p.Tyr715Cys variant in normal fibroblasts recapitulated the probands’ cellular phenotype of enlarged cytoplasmic vacuoles. Fourth, a mouse harboring the heterozygous Y713C variant, which is the equivalent of the human p.Tyr715Cys, resembled the human probands at both the clinical (hypopigmentation, lysosomal storage, brain myelination abnormalities) and cellular (enlarged vacuoles) levels (Figures 4 and 5). Finally, reversing the acidifying effects of the p.Tyr715Cys variant by using the alkalinizing agent chloroquine reduced the number of vacuoles in the probands’ cells (Figure 6), providing further evidence that the vacuolar cellular phenotype is secondary to reduced pH.

The de novo c.2144A>G (p.Tyr715Cys) change in CLCN7 appears to be a gain-of-function variant. Initial indications come from the severe and pleiotropic, but osteopetrosis-free, disease phenotype, which contrasts with the osteopetrosis associated with known inactivating CLCN7 variants. Functional results support this possibility in that they show dramatic increases in chloride transport (Figures 2A and 2B) by the mutant protein compared to the WT. In addition, lysosomes from both probands' fibroblasts were more acidic than normal (Figures 2C and 2D), consistent with increased chloride transport into lysosomes. Although fibroblast cells cultured from Clcn7-knockout mice have normal lysosomal pH,5, 13 the pH is altered in osteoclast lacunae, which use an identical mechanism to acidify, probably with substantially increased proton/Cl− movement.

Our observation that fibroblasts with the gain-of-function CLCN7 variant had altered pH supports the hypothesis that ClC-7 plays a role in regulating lysosomal pH, which has been controversial.5, 6, 12, 22 Our probands reveal that the downstream consequences of a relatively small decrease in lysosomal pH are extensive. A reduction of ∼0.2 pH units (from 4.4 to 4.2) reflects a ∼60% change in the lysosomal free-proton concentration. The extensive pathology observed in the probands is presumably a consequence of reduced lysosomal hydrolase activity at a lowered pH. Indeed, the wide range of findings, many of which resemble sequelae of known lysosomal storage diseases, suggest effects of the pH change on multiple lysosomal hydrolases. Measurement of lysosomal enzymes in fibroblasts, however, was inconclusive because all lysosomal enzyme assays are performed in a buffered solution that fixes the pH at an optimum level for the enzyme assay. Further studies using alternative methods of measuring lysosomal enzymes might help clarify this issue. The hypopigmentation and aberrant melanosomal morphology of our probands also support the importance of melanosomal pH in melanogenesis.32

Interestingly, other studies have documented the presence of large cytoplasmic vacuoles upon treatment with vacuolin-133 or upon overexpression of LIMPII.34 Further studies are required to investigate how reduced lysosomal pH could lead to the formation of intracellular vacuoles and what the origin of these vacuoles is.

In conclusion, the ClC-7 p.Tyr715Cys gain-of-function variant defines a distinct disorder, illustrates the critical role of the ClC-7 chloride/proton antiporter in maintaining lysosomal pH within a very narrow range, and provides a model for investigating regulation of lysosomal acidification. Finally, the salutary effect of chloroquine on lysosomal pH offers promise for therapeutic intervention.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the probands, their families, and the treating physicians for their cooperation, encouragement, and interest. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Undiagnosed Diseases Program, part of the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, was supported by the Common Fund, Office of the Director, NIH. St. Peter’s University Hospital is a designated regional center for general genetic and newborn screening services in New Jersey and is supported, in part, by Special Child Health and Early Intervention Services, New Jersey Department of Health. We thank Emyr Lloyd-Evans for his insightful comments on this manuscript and both the biochemical genetics laboratory at the Greenwood genetic center and Laura Pollard for their help with the measurement of lysosomal enzymes. The CD63 (H5C6), Lamp1 (H4A3), and Lamp2 (H4B4) antibodies developed by J.T. August and J.E.K. Hildreth (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the NIH and maintained at the University of Iowa, Department of Biology. We thank Tim Wood (Greenwood Genetics) for fibroblasts from proband 2 and Forbes Porter, NICHD, for the NPC25 fibroblast line; Cecilia Rivas and Karen Hazzard (NHGRI, NIH) for their assistance in mouse generation; and Calvin Johnson and Huey Cheung, NIH Center for Information Technology, for developing the software used for lysosomal pH quantification.

Published: May 30, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Data can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.04.008.

Contributor Information

Joseph A. Mindell, Email: mindellj@ninds.nih.gov.

May Christine V. Malicdan, Email: malicdanm@mail.nih.gov.

Undiagnosed Diseases Network:

Maria T. Acosta, David R. Adams, Pankaj Agrawal, Mercedes E. Alejandro, Patrick Allard, Justin Alvey, Ashley Andrews, Euan A. Ashley, Mahshid S. Azamian, Carlos A. Bacino, Guney Bademci, Eva Baker, Ashok Balasubramanyam, Dustin Baldridge, Jim Bale, Deborah Barbouth, Gabriel F. Batzli, Pinar Bayrak-Toydemir, Alan H. Beggs, Gill Bejerano, Hugo J. Bellen, Jonathan A. Bernstein, Gerard T. Berry, Anna Bican, David P. Bick, Camille L. Birch, Stephanie Bivona, John Bohnsack, Carsten Bonnenmann, Devon Bonner, Braden E. Boone, Bret L. Bostwick, Lorenzo Botto, Lauren C. Briere, Elly Brokamp, Donna M. Brown, Matthew Brush, Elizabeth A. Burke, Lindsay C. Burrage, Manish J. Butte, John Carey, Olveen Carrasquillo, Ta Chen Peter Chang, Hsiao-Tuan Chao, Gary D. Clark, Terra R. Coakley, Laurel A. Cobban, Joy D. Cogan, F. Sessions Cole, Heather A. Colley, Cynthia M. Cooper, Heidi Cope, William J. Craigen, Precilla D'Souza, Surendra Dasari, Mariska Davids, Jyoti G. Dayal, Esteban C. Dell'Angelica, Shweta U. Dhar, Naghmeh Dorrani, Daniel C. Dorset, Emilie D. Douine, David D. Draper, Laura Duncan, David J. Eckstein, Lisa T. Emrick, Christine M. Eng, Cecilia Esteves, Tyra Estwick, Liliana Fernandez, Carlos Ferreira, Elizabeth L. Fieg, Paul G. Fisher, Brent L. Fogel, Irman Forghani, Laure Fresard, William A. Gahl, Rena A. Godfrey, Alica M. Goldman, David B. Goldstein, Jean-Philippe F. Gourdine, Alana Grajewski, Catherine A. Groden, Andrea L. Gropman, Melissa Haendel, Rizwan Hamid, Neil A. Hanchard, Nichole Hayes, Frances High, Ingrid A. Holm, Jason Hom, Alden Huang, Yong Huang, Rosario Isasi, Fariha Jamal, Yong-hui Jiang, Jean M. Johnston, Angela L. Jones, Lefkothea Karaviti, Emily G. Kelley, Dana Kiley, David M. Koeller, Isaac S. Kohane, Jennefer N. Kohler, Deborah Krakow, Donna M. Krasnewich, Susan Korrick, Mary Koziura, Joel B. Krier, Jennifer E. Kyle, Seema R. Lalani, Byron Lam, Brendan C. Lanpher, Ian R. Lanza, C. Christopher Lau, Jozef Lazar, Kimberly LeBlanc, Brendan H. Lee, Hane Lee, Roy Levitt, Shawn E. Levy, Richard A. Lewis, Sharyn A. Lincoln, Pengfei Liu, Xue Zhong Liu, Nicola Longo, Sandra K. Loo, Joseph Loscalzo, Richard L. Maas, Ellen F. Macnamara, Calum A. MacRae, Valerie V. Maduro, Marta M. Majcherska, May Christine V. Malicdan, Laura A. Mamounas, Teri A. Manolio, Rong Mao, Thomas C. Markello, Ronit Marom, Gabor Marth, Beth A. Martin, Martin G. Martin, Julian A. Martínez-Agosto, Shruti Marwaha, Thomas May, Jacob McCauley, Allyn McConkie-Rosell, Colleen E. McCormack, Alexa T. McCray, Thomas O. Metz, Matthew Might, Eva Morava-Kozicz, Paolo M. Moretti, Marie Morimoto, John J. Mulvihill, David R. Murdock, Avi Nath, Stan F. Nelson, J. Scott Newberry, John H. Newman, Sarah K. Nicholas, Donna Novacic, Devin Oglesbee, James P. Orengo, Laura Pace, Stephen Pak, J. Carl Pallais, Christina G.S. Palmer, Jeanette C. Papp, Neil H. Parker, John A. Phillips, III, Jennifer E. Posey, John H. Postlethwait, Lorraine Potocki, Barbara N. Pusey, Aaron Quinlan, Archana N. Raja, Genecee Renteria, Chloe M. Reuter, Lynette Rives, Amy K. Robertson, Lance H. Rodan, Jill A. Rosenfeld, Robb K. Rowley, Maura Ruzhnikov, Ralph Sacco, Jacinda B. Sampson, Susan L. Samson, Mario Saporta, Judy Schaechter, Timothy Schedl, Kelly Schoch, Daryl A. Scott, Lisa Shakachite, Prashant Sharma, Vandana Shashi, Kathleen Shields, Jimann Shin, Rebecca Signer, Catherine H. Sillari, Edwin K. Silverman, Janet S. Sinsheimer, Kathy Sisco, Kevin S. Smith, Lilianna Solnica-Krezel, Rebecca C. Spillmann, Joan M. Stoler, Nicholas Stong, Jennifer A. Sullivan, Shirley Sutton, David A. Sweetser, Holly K. Tabor, Cecelia P. Tamburro, Queenie K.-G. Tan, Mustafa Tekin, Fred Telischi, Willa Thorson, Cynthia J. Tifft, Camilo Toro, Alyssa A. Tran, Tiina K. Urv, Matt Velinder, Dave Viskochil, Tiphanie P. Vogel, Colleen E. Wahl, Nicole M. Walley, Chris A. Walsh, Melissa Walker, Jennifer Wambach, Jijun Wan, Lee-kai Wang, Michael F. Wangler, Patricia A. Ward, Katrina M. Waters, Bobbie-Jo M. Webb-Robertson, Daniel Wegner, Monte Westerfield, Matthew T. Wheeler, Anastasia L. Wise, Lynne A. Wolfe, Jeremy D. Woods, Elizabeth A. Worthey, Shinya Yamamoto, John Yang, Amanda J. Yoon, Guoyun Yu, Diane B. Zastrow, Chunli Zhao, and Stephan Zuchner

Accession Numbers

The ClinVar accession number for the variant c.2144A>G (p.Tyr715Cys, GenBank: NM_001287.5) reported in this study is ClinVar: RCV000412760.1.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes Project 11_2010 data release project, ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/1000genomes/ftp/release/20100804/

Babraham Bioinformatics, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

ClinVar Database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/

CRISPRscan, http://www.crisprscan.org/

ESP: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project, https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/

EVS: NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project EVS v.0.0.30, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), http://exac.broadinstitute.org [date last accessed, January, 2019]

Gene Ontology, http://geneontology.org/

Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), https://omim.org/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Hamer I., Van Beersel G., Arnould T., Jadot M. Lipids and lysosomes. Curr. Drug Metab. 2012;13:1371–1387. doi: 10.2174/138920012803762684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hamer, I., Van Beersel, G., Arnould, T., and Jadot, M. (2012). Lipids and lysosomes. Curr. Drug Metab. 13, 1371-1387. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mindell J.A. Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012;74:69–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mindell, J.A. (2012). Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 69-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Xiong J., Zhu M.X. Regulation of lysosomal ion homeostasis by channels and transporters. Sci. China Life Sci. 2016;59:777–791. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-5090-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xiong, J., and Zhu, M.X. (2016). Regulation of lysosomal ion homeostasis by channels and transporters. Sci. China Life Sci. 59, 777-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Devuyst O., Christie P.T., Courtoy P.J., Beauwens R., Thakker R.V. Intra-renal and subcellular distribution of the human chloride channel, CLC-5, reveals a pathophysiological basis for Dent’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:247–257. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Devuyst, O., Christie, P.T., Courtoy, P.J., Beauwens, R., and Thakker, R.V. (1999). Intra-renal and subcellular distribution of the human chloride channel, CLC-5, reveals a pathophysiological basis for Dent’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 247-257. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kasper D., Planells-Cases R., Fuhrmann J.C., Scheel O., Zeitz O., Ruether K., Schmitt A., Poët M., Steinfeld R., Schweizer M. Loss of the chloride channel ClC-7 leads to lysosomal storage disease and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2005;24:1079–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kasper, D., Planells-Cases, R., Fuhrmann, J.C., Scheel, O., Zeitz, O., Ruether, K., Schmitt, A., Poet, M., Steinfeld, R., Schweizer, M., et al. (2005). Loss of the chloride channel ClC-7 leads to lysosomal storage disease and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 24, 1079-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kornak U., Kasper D., Bösl M.R., Kaiser E., Schweizer M., Schulz A., Friedrich W., Delling G., Jentsch T.J. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kornak, U., Kasper, D., Bosl, M.R., Kaiser, E., Schweizer, M., Schulz, A., Friedrich, W., Delling, G., and Jentsch, T.J. (2001). Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell 104, 205-215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mohammad-Panah R., Ackerley C., Rommens J., Choudhury M., Wang Y., Bear C.E. The chloride channel ClC-4 co-localizes with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and may mediate chloride flux across the apical membrane of intestinal epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:566–574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mohammad-Panah, R., Ackerley, C., Rommens, J., Choudhury, M., Wang, Y., and Bear, C.E. (2002). The chloride channel ClC-4 co-localizes with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and may mediate chloride flux across the apical membrane of intestinal epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 566-574. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Poët M., Kornak U., Schweizer M., Zdebik A.A., Scheel O., Hoelter S., Wurst W., Schmitt A., Fuhrmann J.C., Planells-Cases R. Lysosomal storage disease upon disruption of the neuronal chloride transport protein ClC-6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13854–13859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606137103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Poet, M., Kornak, U., Schweizer, M., Zdebik, A.A., Scheel, O., Hoelter, S., Wurst, W., Schmitt, A., Fuhrmann, J.C., Planells-Cases, R., et al. (2006). Lysosomal storage disease upon disruption of the neuronal chloride transport protein ClC-6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13854-13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Stobrawa S.M., Breiderhoff T., Takamori S., Engel D., Schweizer M., Zdebik A.A., Bösl M.R., Ruether K., Jahn H., Draguhn A. Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stobrawa, S.M., Breiderhoff, T., Takamori, S., Engel, D., Schweizer, M., Zdebik, A.A., Bosl, M.R., Ruether, K., Jahn, H., Draguhn, A., et al. (2001). Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron 29, 185-196. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Graves A.R., Curran P.K., Smith C.L., Mindell J.A. The Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature. 2008;453:788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature06907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Graves, A.R., Curran, P.K., Smith, C.L., and Mindell, J.A. (2008). The Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature 453, 788-792. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Majumdar A., Capetillo-Zarate E., Cruz D., Gouras G.K., Maxfield F.R. Degradation of Alzheimer’s amyloid fibrils by microglia requires delivery of ClC-7 to lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:1664–1676. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-09-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Majumdar, A., Capetillo-Zarate, E., Cruz, D., Gouras, G.K., and Maxfield, F.R. (2011). Degradation of Alzheimer’s amyloid fibrils by microglia requires delivery of ClC-7 to lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1664-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Steinberg B.E., Huynh K.K., Brodovitch A., Jabs S., Stauber T., Jentsch T.J., Grinstein S. A cation counterflux supports lysosomal acidification. J. Cell Biol. 2010;189:1171–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Steinberg, B.E., Huynh, K.K., Brodovitch, A., Jabs, S., Stauber, T., Jentsch, T.J., and Grinstein, S. (2010). A cation counterflux supports lysosomal acidification. J. Cell Biol. 189, 1171-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Weinert S., Jabs S., Supanchart C., Schweizer M., Gimber N., Richter M., Rademann J., Stauber T., Kornak U., Jentsch T.J. Lysosomal pathology and osteopetrosis upon loss of H+-driven lysosomal Cl- accumulation. Science. 2010;328:1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1188072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Weinert, S., Jabs, S., Supanchart, C., Schweizer, M., Gimber, N., Richter, M., Rademann, J., Stauber, T., Kornak, U., and Jentsch, T.J. (2010). Lysosomal pathology and osteopetrosis upon loss of H+-driven lysosomal Cl- accumulation. Science 328, 1401-1403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gahl W.A., Mulvihill J.J., Toro C., Markello T.C., Wise A.L., Ramoni R.B., Adams D.R., Tifft C.J., UDN The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program and Network: Applications to modern medicine. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016;117:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gahl, W.A., Mulvihill, J.J., Toro, C., Markello, T.C., Wise, A.L., Ramoni, R.B., Adams, D.R., and Tifft, C.J.; UDN (2016). The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program and Network: Applications to modern medicine. Mol. Genet. Metab. 117, 393-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gahl W.A., Wise A.L., Ashley E.A. The Undiagnosed Diseases Network of the National Institutes of Health: A National Extension. JAMA. 2015;314:1797–1798. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gahl, W.A., Wise, A.L., and Ashley, E.A. (2015). The Undiagnosed Diseases Network of the National Institutes of Health: A National Extension. JAMA 314, 1797-1798. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Malicdan M.C.V., Vilboux T., Stephen J., Maglic D., Mian L., Konzman D., Guo J., Yildirimli D., Bryant J., Fischer R., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Mutations in human homologue of chicken talpid3 gene (KIAA0586) cause a hybrid ciliopathy with overlapping features of Jeune and Joubert syndromes. J. Med. Genet. 2015;52:830–839. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Malicdan, M.C.V., Vilboux, T., Stephen, J., Maglic, D., Mian, L., Konzman, D., Guo, J., Yildirimli, D., Bryant, J., Fischer, R., et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2015). Mutations in human homologue of chicken talpid3 gene (KIAA0586) cause a hybrid ciliopathy with overlapping features of Jeune and Joubert syndromes. J. Med. Genet. 52, 830-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tycko B., Keith C.H., Maxfield F.R. Rapid acidification of endocytic vesicles containing asialoglycoprotein in cells of a human hepatoma line. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:1762–1776. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.6.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tycko, B., Keith, C.H., and Maxfield, F.R. (1983). Rapid acidification of endocytic vesicles containing asialoglycoprotein in cells of a human hepatoma line. J. Cell Biol. 97, 1762-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Liman E.R., Tytgat J., Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Liman, E.R., Tytgat, J., and Hess, P. (1992). Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron 9, 861-871. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Moreno-Mateos M.A., Vejnar C.E., Beaudoin J.D., Fernandez J.P., Mis E.K., Khokha M.K., Giraldez A.J. CRISPRscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:982–988. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Moreno-Mateos, M.A., Vejnar, C.E., Beaudoin, J.D., Fernandez, J.P., Mis, E.K., Khokha, M.K., and Giraldez, A.J. (2015). CRISPRscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods 12, 982-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Behringer R., Gertsenstein M., Nagy K.V., Nagy A. Fourth Edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2014. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]; Behringer, R., Gertsenstein, M., Nagy, K.V., and Nagy, A. (2014). Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, Fourth Edition (New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- 21.Vilboux T., Malicdan M.C., Chang Y.M., Guo J., Zerfas P.M., Stephen J., Cullinane A.R., Bryant J., Fischer R., Brooks B.P., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Cystic cerebellar dysplasia and biallelic LAMA1 mutations: a lamininopathy associated with tics, obsessive compulsive traits and myopia due to cell adhesion and migration defects. J. Med. Genet. 2016;53:318–329. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vilboux, T., Malicdan, M.C., Chang, Y.M., Guo, J., Zerfas, P.M., Stephen, J., Cullinane, A.R., Bryant, J., Fischer, R., Brooks, B.P., et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2016). Cystic cerebellar dysplasia and biallelic LAMA1 mutations: a lamininopathy associated with tics, obsessive compulsive traits and myopia due to cell adhesion and migration defects. J. Med. Genet. 53, 318-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jentsch T.J. Chloride and the endosomal-lysosomal pathway: emerging roles of CLC chloride transporters. J. Physiol. 2007;578:633–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jentsch, T.J. (2007). Chloride and the endosomal-lysosomal pathway: emerging roles of CLC chloride transporters. J. Physiol. 578, 633-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jentsch T.J., Poët M., Fuhrmann J.C., Zdebik A.A. Physiological functions of CLC Cl- channels gleaned from human genetic disease and mouse models. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:779–807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.153245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jentsch, T.J., Poet, M., Fuhrmann, J.C., and Zdebik, A.A. (2005). Physiological functions of CLC Cl- channels gleaned from human genetic disease and mouse models. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 779-807. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kieferle S., Fong P., Bens M., Vandewalle A., Jentsch T.J. Two highly homologous members of the ClC chloride channel family in both rat and human kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6943–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kieferle, S., Fong, P., Bens, M., Vandewalle, A., and Jentsch, T.J. (1994). Two highly homologous members of the ClC chloride channel family in both rat and human kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6943-6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Steinmeyer K., Ortland C., Jentsch T.J. Primary structure and functional expression of a developmentally regulated skeletal muscle chloride channel. Nature. 1991;354:301–304. doi: 10.1038/354301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Steinmeyer, K., Ortland, C., and Jentsch, T.J. (1991). Primary structure and functional expression of a developmentally regulated skeletal muscle chloride channel. Nature 354, 301-304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Thiemann A., Gründer S., Pusch M., Jentsch T.J. A chloride channel widely expressed in epithelial and non-epithelial cells. Nature. 1992;356:57–60. doi: 10.1038/356057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Thiemann, A., Grunder, S., Pusch, M., and Jentsch, T.J. (1992). A chloride channel widely expressed in epithelial and non-epithelial cells. Nature 356, 57-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Uchida S., Sasaki S., Furukawa T., Hiraoka M., Imai T., Hirata Y., Marumo F. Molecular cloning of a chloride channel that is regulated by dehydration and expressed predominantly in kidney medulla. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:19192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Uchida, S., Sasaki, S., Furukawa, T., Hiraoka, M., Imai, T., Hirata, Y., and Marumo, F. (1994). Molecular cloning of a chloride channel that is regulated by dehydration and expressed predominantly in kidney medulla. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19192. [PubMed]

- 28.Chalhoub N., Benachenhou N., Rajapurohitam V., Pata M., Ferron M., Frattini A., Villa A., Vacher J. Grey-lethal mutation induces severe malignant autosomal recessive osteopetrosis in mouse and human. Nat. Med. 2003;9:399–406. doi: 10.1038/nm842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chalhoub, N., Benachenhou, N., Rajapurohitam, V., Pata, M., Ferron, M., Frattini, A., Villa, A., and Vacher, J. (2003). Grey-lethal mutation induces severe malignant autosomal recessive osteopetrosis in mouse and human. Nat. Med. 9, 399-406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lange P.F., Wartosch L., Jentsch T.J., Fuhrmann J.C. ClC-7 requires Ostm1 as a beta-subunit to support bone resorption and lysosomal function. Nature. 2006;440:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature04535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lange, P.F., Wartosch, L., Jentsch, T.J., and Fuhrmann, J.C. (2006). ClC-7 requires Ostm1 as a beta-subunit to support bone resorption and lysosomal function. Nature 440, 220-223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Cleiren E., Bénichou O., Van Hul E., Gram J., Bollerslev J., Singer F.R., Beaverson K., Aledo A., Whyte M.P., Yoneyama T. Albers-Schönberg disease (autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, type II) results from mutations in the ClCN7 chloride channel gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2861–2867. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cleiren, E., Benichou, O., Van Hul, E., Gram, J., Bollerslev, J., Singer, F.R., Beaverson, K., Aledo, A., Whyte, M.P., Yoneyama, T., et al. (2001). Albers-Schonberg disease (autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, type II) results from mutations in the ClCN7 chloride channel gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2861-2867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Leisle L., Ludwig C.F., Wagner F.A., Jentsch T.J., Stauber T. ClC-7 is a slowly voltage-gated 2Cl(-)/1H(+)-exchanger and requires Ostm1 for transport activity. EMBO J. 2011;30:2140–2152. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Leisle, L., Ludwig, C.F., Wagner, F.A., Jentsch, T.J., and Stauber, T. (2011). ClC-7 is a slowly voltage-gated 2Cl(-)/1H(+)-exchanger and requires Ostm1 for transport activity. EMBO J. 30, 2140-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Ancans J., Tobin D.J., Hoogduijn M.J., Smit N.P., Wakamatsu K., Thody A.J. Melanosomal pH controls rate of melanogenesis, eumelanin/phaeomelanin ratio and melanosome maturation in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;268:26–35. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ancans, J., Tobin, D.J., Hoogduijn, M.J., Smit, N.P., Wakamatsu, K., and Thody, A.J. (2001). Melanosomal pH controls rate of melanogenesis, eumelanin/phaeomelanin ratio and melanosome maturation in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 268, 26-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Lu Y., Dong S., Hao B., Li C., Zhu K., Guo W., Wang Q., Cheung K.H., Wong C.W., Wu W.T. Vacuolin-1 potently and reversibly inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion by activating RAB5A. Autophagy. 2014;10:1895–1905. doi: 10.4161/auto.32200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lu, Y., Dong, S., Hao, B., Li, C., Zhu, K., Guo, W., Wang, Q., Cheung, K.H., Wong, C.W., Wu, W.T., et al. (2014). Vacuolin-1 potently and reversibly inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion by activating RAB5A. Autophagy 10, 1895-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kuronita T., Eskelinen E.L., Fujita H., Saftig P., Himeno M., Tanaka Y. A role for the lysosomal membrane protein LGP85 in the biogenesis and maintenance of endosomal and lysosomal morphology. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:4117–4131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kuronita, T., Eskelinen, E.L., Fujita, H., Saftig, P., Himeno, M., and Tanaka, Y. (2002). A role for the lysosomal membrane protein LGP85 in the biogenesis and maintenance of endosomal and lysosomal morphology. J. Cell Sci. 115, 4117-4131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Sanchez C.E., Richards J.E., Almli C.R. Neurodevelopmental MRI brain templates for children from 2 weeks to 4 years of age. Dev. Psychobiol. 2012;54:77–91. doi: 10.1002/dev.20579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sanchez, C.E., Richards, J.E., and Almli, C.R. (2012). Neurodevelopmental MRI brain templates for children from 2 weeks to 4 years of age. Dev. Psychobiol. 54, 77-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.