Abstract

A 48-year-old man with a history of cerebral infarction presented with gross hematuria. The patient's limping accompanies twisting trunk on his walking. The diagnosis was right upper ureteral stone. Prior to Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) ureteral stent was inserted. After the second ESWL ureteral stent was displaced upwardly without patient's unknown. Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) was performed for both removal of ureteral stent and fragmentation of residual stone. Spontaneously, post RIRS ureteral stent was migrated upwardly to the same position.

Ureteral stent migration is uncommon. Twisting walk may cause the position of ureteral stent upwardly.

Introduction

Ureteral stent migration has rarely been reported, with a small incidence rate of 2%–10%.1 It is one of the complications of ureteral stent placement, which also includes stent migration, encrustation, stone formation, and fragmentation.1, 2, 3 Although most cases occurred as a late complication, no precise period has been mentioned. Prior to extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) in larger stones, a ureteral stent is inserted to prevent the occurrence of complication after ESWL. Repeated ureteral stent migration has however never been reported.

We described a case of repeated spontaneous migration of ureteral stent during a series of lithotripsy in a patient with hemiplegia.

Case report

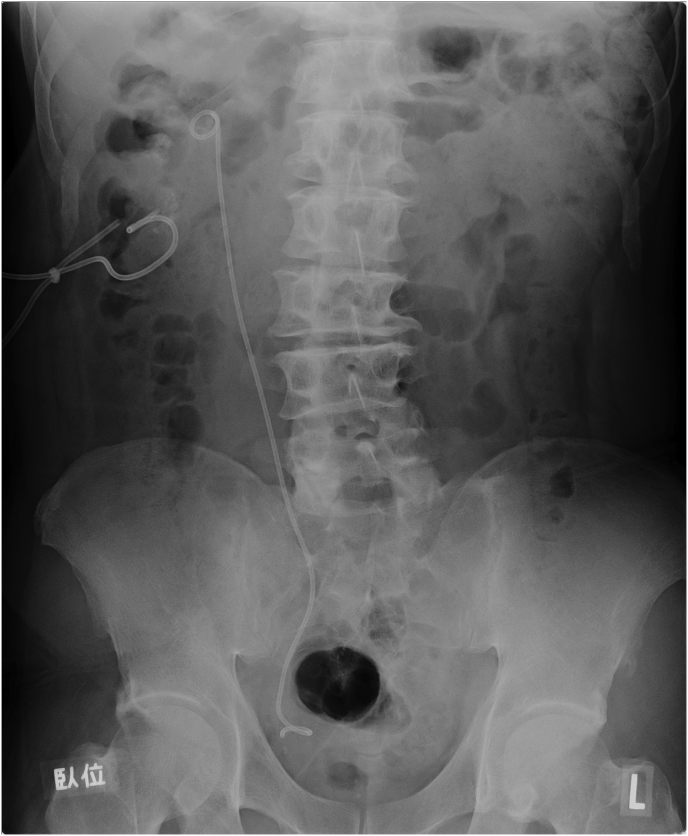

A 48-year-old man with a history of cerebral infarction presented with gross hematuria and pain in the right flank. The patient was consulted for a 13 × 20-mm, right upper ureteral stone. Before ESWL, a 4.7-Fr ureteral stent was inserted for the prevention of stonestreet. ESWL was performed twice, but the ureteral stone could not be completely fragmented. After 2 months, an X-ray kidney–ureter–bladder (KUB) showed proximal stent migration at the level of 3rd lumbar vertebra with patient's unknown (Fig. 1). To remove the ureteral stent and achieve stone-free status, the patient was sent to our hospital. At presentation, the patient was afebrile with stable vital signs, and his laboratory values were consistent with his baseline values. KUB revealed a 10 × 13-mm, right upper ureteral stone. Furthermore, abdominal ultrasonography showed severe hydronephrosis.

Fig. 1.

KUB showing upward ureteral stent migration after 2 months of the second ESWL.

Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) was performed a month after the initial consultation. First, the migrated stent was removed using forceps through rigid ureteroscopy. Second, laser lithotomy was performed, and whole residual stones were completely fragmented. Lastly, a new 6-Fr ureteral stent was inserted into the right ureter. KUB and cystoscopy found no evidence of extremely short length in stent during operation (Fig. 2). After 2 weeks, KUB showed proximal stent displacement again in the same position (Fig. 3). A few weeks later, the displaced stent was removed by the same 3-Fr forceps through rigid ureteroscopy. A new stent was placed in the right ureter with a string and then removed 2 days postoperatively, which prevented ureteral stent from re-displacement. After stent removal, the patient did not show any symptoms including flank pain or urinary tract infection.

Fig. 2.

KUB showing correct ureteral stent insertion immediately after RIRS.

Fig. 3.

KUB showing repeated ureteral stent migration to the same position 2 weeks after RIRS.

Discussion

The most common complications of the ureteral stent are lower abdominal discomfort or gross hematuria.2 Ureteral stent migration has rarely been reported. Migration to the extraureteral space has also been reported,4 wherein intravenous procedure was required to eliminate the ureteral stent, thereby forcing the patient to undergo invasive treatment. Similar to our case, in another case, invasive procedure was not needed because of intraureteral malposition; however, once a proximal ureteral malposition was detected, a longer stent was selected for the next placement as no repeated displacement occurred with a longer stent.2

The possible mechanism in our case is considerable as follows: the patient developed hemiplegia on the left side after cerebral infarction. Limping accompanies twisting trunk on his walking. Twisting may cause excessive movement of the ureteral stent toward the proximal urinary system. Repeating such a strange movement may lead to upward disposition of the ureteral stent. Deep massage has also been associated with ureteral stent displacement.5 Outer force may change the position of the ureteral stent. This report may support the phenomenon of our case. Although there was no outer force in this case, inner twisting abdominal movement possibly resulted in enough pressure to cause movement of the ureteral stent.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of repeated spontaneous migration of ureteral catheter during a short period in a patient with hemiplegia. To avoid migration, quick removal of the ureteral stent should be considered (unless long-term placement is required); also, outer pressure to the body such as body massage should be avoided.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethical statements

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution. Informed consent to perform operation was obtained from all patients, but informed consent to be included in this study was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100854.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hao P., Li W., Song C., Yan J., Song B., Li L. Clinical evaluation of double-pigtail stent in patients with upper urinary tract diseases: report of 2685 cases. J Endourol. 2008;22(1):65–70. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breau R.H., Norman R.W. Optimal prevention and management of proximal ureteral stent migration and remigration. J Urol. 2001;166:890–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringel A., Richter S., Shalev M., Nissenkom I. Late complication of ureteral stents. Eur Urol. 2000;38(1):41–44. doi: 10.1159/000020250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falahatkar S., Hemmati H., Gholamjani Moghaddam K. Intracaval migration: an uncommon complication of ureteral Double-J stent placement. J Endourol. 2012;26(2):119–121. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr H.D. Ureteral stent displacement associated with deep massage. Wis Med J. 1997;96(12):57–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.