Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology, including the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) species and tau pathology, begins decades before the onset of cognitive impairment. This long preclinical period provides an opportunity for clinical trials designed to prevent or delay the onset of cognitive impairment due to AD. Under the umbrella of the Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative Generation Program, therapies targeting Aβ, including CNP520 (umibecestat), a β-site-amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE-1) inhibitor, and CAD106, an active Aβ immunotherapy, are in clinical development in preclinical AD.

Methods

The Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative Generation Program comprises two pivotal (phase 2/3) studies that assess the efficacy and safety of umibecestat and CAD106 in cognitively unimpaired individuals with high risk for developing symptoms of AD based on their age (60–75 years), APOE4 genotype, and, for heterozygotes (APOE ε2/ε4 or ε3/ε4), elevated brain amyloid. Approximately, 3500 individuals will be enrolled in either Generation Study 1 (randomized to cohort 1 [CAD106 injection or placebo, 5:3] or cohort 2 [oral umibecestat 50 mg or placebo, 3:2]) or Generation Study 2 (randomized to oral umibecestat 50 mg and 15 mg, or placebo [2:1:2]). Participants receive treatment for at least 60 months and up to a maximum of 96 months. Primary outcomes include time to event, with event defined as diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to AD and/or dementia due to AD, and the Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative preclinical composite cognitive test battery. Secondary endpoints include the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status total score, Everyday Cognition Scale, biomarkers, and brain imaging.

Discussion

The Generation Program is designed to assess the efficacy, safety, and biomarker effects of the two treatments in individuals at high risk for AD. It may also provide a plausible test of the amyloid hypothesis and further accelerate the evaluation of AD prevention therapies.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Preclinical Alzheimer's disease, Mild cognitive impairment, Umibecestat, CNP520, BACE-1 inhibitor, CAD106, Generation Program, Alzheimer's prevention initiative

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia [1]. The only therapies available for patients with AD, such as cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, target the symptoms of the disease, but these treatments do not slow disease progression [2]. There is a high unmet need for treatments that target the underlying disease pathophysiology at early stages, with the goal of slowing progression, delaying, or even preventing the onset of clinical symptoms due to AD.

Substantial evidence from genetically at-risk groups and otherwise cognitively unimpaired individuals suggests progressive biomarker changes before cognitive impairment [1], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. One critical change is the slow accumulation of pathological amyloid beta (Aβ) species in the brain [10], [11], [12], which starts a decade or more before the symptoms occur. Investigational treatments targeting the AD pathogenic cascade include those that interfere with the production, accumulation, or toxic sequelae of Aβ. Based on nonclinical studies and lack of benefit in recent clinical trials targeting symptomatic stages of the disease, the current hypothesis is that Aβ-lowering therapies might only be effective in preventing or slowing the progression of AD when initiated in the preclinical stages of the disease (i.e., before symptoms, and irreversible synaptic or neuronal loss) [4], [10], [13].

Although some recent trials confirmed that antiamyloid drugs could induce a measurable Aβ reduction [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], this reduction generally did not correlate with improvements in cognition in the early or mild AD stages. One explanation for these failures (in addition to potentially inadequate dosing or study design elements) is that the Aβ deposition is an early-stage process, and antiamyloid therapies may have little clinical effect in patients who are at clinical stages.

As the understanding of AD has advanced, biomarkers may be used to enrich the study population based on genetics and factors underlying AD pathophysiology, and trials can enroll cognitively unimpaired participants at earlier stages of the disease (i.e., preclinical AD). Without a genetic or biomarker enrichment strategy, a very large number of cognitively unimpaired persons studied over many years would be required to conduct prevention trials [20], [21].

The Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative (API) was established in 2010 to help accelerate the evaluation of promising AD prevention therapies [20], [21], [22], [23]. The aims of the API include conducting potentially label-enabling trials in cognitively unimpaired persons at high risk for the development of AD using novel composite clinical endpoints, thereby providing better tests of the amyloid hypothesis than trials that recently failed in clinical stages of the disease [19], [24]. An initial trial was launched in members from the world's largest autosomal dominant AD kindred in Colombia (i.e., persons at virtually certain genetic risk for early-onset AD), with the intention of following on with the trials described here [25]. The trials are also designed to assess the relationship between biomarker status and clinical benefits of treatment to support the development of surrogate endpoints for predicting clinical benefits in future prevention trials. Finally, the API was designed as a series of public–private partnerships that would identify large numbers of interested research participants who might enroll in a range of studies (e.g., through the Alzheimer's Prevention Registry [www.endALZnow.org]), and that would share baseline and post-trial data, to help find effective AD prevention therapies as soon as possible.

The studies discussed here (collectively called the Generation Program) are sponsored by Novartis and Amgen in collaboration with the Banner Alzheimer's Institute, and supported partially by funding from the National Institute on Aging and philanthropy, for the development of new potential prevention treatment(s) for AD [26]. The Generation Program consists of two phase 2/3 studies of similar design that will evaluate the effects of two amyloid-targeted therapies in cognitively unimpaired participants (Table 1). Umibecestat (CNP520) is an orally available β-site-amyloid precursor protein (APP) cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE-1) inhibitor; CAD106 is an active, second-generation Aβ immunotherapy.

Table 1.

Generation Program overview

| Design feature | Generation Study 1 | Generation Study 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | |

| Inclusion: genetic risk | APOE4 homozygote | APOE4 carriers (homozygote + heterozygote) |

| Inclusion: amyloid biomarker | None (eligible with elevated or nonelevated amyloid) | Elevated amyloid required for heterozygotes (detected by amyloid PET or CSF) |

| Age at entry | 60–75 | |

| Clinical status | Cognitively normal | |

| Primary endpoints (dual; success required on either) |

|

|

| Treatment duration |

|

|

| Sample size/investigational drug | 1340 CAD106/matching PBO OR umibecestat 50 mg/matching PBO |

∼2000 umibecestat 15 mg/50 mg/PBO |

Abbreviations: APCC, API Preclinical Composite Cognitive Battery; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PBO, placebo; PET, positron emission tomography; homozygote, APOE ε4/ε4; heterozygote, APOE ε2/ε4 or ε3/ε4.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study aims and objectives

The purpose of these studies is to determine the effects of the amyloid-targeting therapies umibecestat (Generation Study 1 and 2) or CAD106 (Generation Study 1 only) on cognition, global clinical status, and on AD biomarkers in cognitively unimpaired individuals who are at high risk for the development of clinical symptoms of AD based on their age, genetics (presence of APOE4 allele), and, for APOE4 heterozygotes (HTs; APOE ε2/ε4 or ε3/ε4), elevation of amyloid pathology in the brain. The objective of the Generation Program is to determine whether early treatment with umibecestat and/or CAD106 can slow progression, delay, or even prevent the onset of clinical symptoms due to AD. Description of this study protocol conforms to the 2013 Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials [27], [28].

Both studies use the same dual primary outcomes: time to event (TTE), with event defined as diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD and/or dementia due to AD, and change from the baseline to month 60 on API preclinical composite cognitive (APCC) test score. Each trial will be successful if positive results are obtained in at least one of the two endpoints. This approach allows examination of drug effects on two clinically relevant measures of disease progression. Furthermore, this mitigates the risk of an uninformative trial if one of the two primary outcomes does not perform as predicted.

Other outcome measures included in these studies are the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes, a global cognitive and functional measure widely used in clinical research in AD [29]; Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status total score, a clinical tool used to assess neuropsychological status [30]; and the Everyday Cognition Scale, a measurement of daily function [31]. Safety outcomes are assessed via physical and neurological examinations, laboratory assessments, electrocardiography (ECG), brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, adverse event (AE), and serious AE reporting, and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale [32]. Imaging and fluid-based AD biomarkers are also evaluated, for example, volumetric MRI and functional resting-state MRI, amyloid positron emission tomography (PET), fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET (study 1 only), tau PET, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-based and blood-based assessments. The impact of APOE4/amyloid-related risk disclosure is assessed with the six-item subset of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults for short-term impact and the Geriatric Depression Scale for long-term impact in both trials. In addition, study 1 includes a full battery to assess the impact of APOE4 genotype disclosure over 12 months. The primary, secondary, and exploratory objectives of the Generation studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key study objectives for the Generation Program

| Objectives |

|---|

Primary objective

|

Secondary objectives

|

Exploratory objectives

|

NOTE. *Generation Study 2 investigates the use of umibecestat versus placebo only; Control: Generation Study 1 matching placebo group, Generation Study 2 placebo group.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; AE, adverse event; APCC, API preclinical composite cognitive battery; API, Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative; CDR-SOB, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ECog, Everyday Cognition Scale; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; TTE, time to event.

2.2. Study design

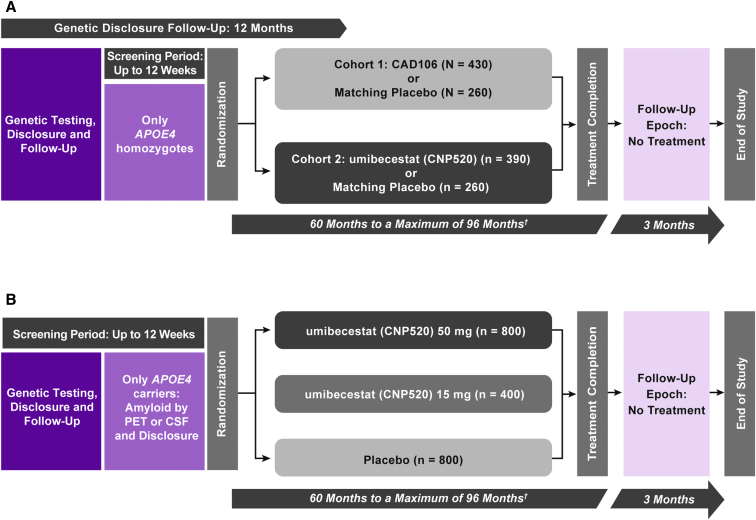

The Generation Program studies have screening, treatment, and follow-up periods (Fig. 1). Generation Study 1 also has a prescreening period with an extended 12-month genetic disclosure follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Study design of (A) Generation Study 1 and (B) Generation Study 2; (A) The study population comprises cognitively unimpaired men or women aged 60–75 years homozygous for APOE4 (APOE ε4/ε4). (B) The study population comprises cognitively unimpaired men or women aged 60–75 years homozygous or heterozygous (APOE ε2/ε4 or ε3/ε4) for APOE4; if participants are heterozygous, they should also be amyloid positive by PET or CSF. †Variable treatment duration to obtain target number of events. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PET, positron emission tomography.

2.3. Study population

Generation Study 1 will enroll 1340 participants who are 60–75 years old, APOE4 homozygotes (HMs; ε4/ε4), and Generation Study 2 will enroll approximately 2000 APOE4 carriers (both HMs and HTs), with the additional requirement for HTs to have elevated brain amyloid levels as ascertained by amyloid PET imaging or lumbar puncture for CSF. Enrolled participants must be cognitively unimpaired, assessed as psychologically ready and willing to receive their individual results for APOE genotyping (and amyloid status for Generation Study 2 only) and to have a study partner willing to provide insight into their health status, cognitive, functional and behavioral changes, and compliance. Individuals with current neurological conditions; severe, progressive, or unstable disease that may interfere with the study assessments; safety-related brain MRI findings that could lead to cognitive decline; or history of malignancy are excluded from the studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Key inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening in the Generation Program

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

NOTE. *Generation Study 2 only; †If the RBANS delayed memory index score is between 70 and 84 (inclusive) and the global CDR score = 0, the participant may be allowed to continue only if the investigator judges that cognition is unimpaired following review of the MCI/dementia criteria. If the global CDR score = 0.5 and the RBANS delayed memory index score is 85 or greater, the participant may be allowed to continue only if the investigator judges that cognition is unimpaired following review of the MCI/dementia criteria.

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ECG, electrocardiogram; eC-SSRS, electronic C-SSRS; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; homozygous, APOE ε4/ε4; heterozygous, APOE ε2/ε4 or ε3/ε4.

2.4. Participant screening and genetic disclosure

Generation Study 1 includes a prescreening period: this phase includes evaluation and disclosure of the APOE genotype with a separate informed consent form. Clinically eligible participants, after confirmation of psychological readiness, receive disclosure of their risk estimate for developing clinical symptoms of AD based on their age and genotype [33]. Participants are followed up using a telephone-based psychological battery administered 2–7 days, 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after disclosure to assess psychological response to having received genotype and risk information; these assessments are concurrent with other study assessments for HMs who enroll in the screening period. Eligible HMs are invited to sign a second informed consent form with detailed study information, including safety assessments; cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric scales; and brain MRI scans. Amyloid PET is required, whereas FDG PET, tau PET, and lumbar punctures are optional.

Generation Study 2 starts with the screening period, including the genotyping step. Similar to Generation Study 1, participants who have been confirmed as psychologically ready will receive disclosure of their risk estimate to develop clinical symptoms of AD based on their age and genotype. A single disclosure follow-up is scheduled 2–7 days after the genetic disclosure. Only APOE4 carriers continue with the remaining screening assessments, which include safety tests, cognitive and neurological scales, brain MRI scan, tau PET, and amyloid PET scan and/or lumbar puncture (either one is mandatory at screening to determine brain amyloid levels), and disclosure of amyloid status, with follow-up 2–7 days later.

2.5. Study treatment period

2.5.1. Study interventions

The API Treatment Selection Advisory Committee vetted candidate treatments based on target engagement and safety and tolerability data. The two investigational products tested in the Generation Program were selected based on their profiles and Novartis' willingness to support API's general scientific goals.

CAD106 is a second-generation active Aβ immunotherapy that effectively induced Aβ antibodies in animal models and humans without activating an Aβ-specific T-cell response [34], [35], [36], [37]. Clinical data generated so far include a total of four double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical studies in patients with AD and two open-label extension studies [37]. Across all studies in 206 patients with predominantly mild AD, CAD106 showed acceptable safety and tolerability, and a biomarker profile largely consistent with the expected effects of an Aβ immunotherapy. The combination of CAD106 450 μg plus alum 450 μg was identified as the best regimen associated with strong and persistent Aβ-immunoglobulin G response and suitable tolerability profile for long-term clinical studies [34]. CAD106 is being tested in cohort 1 of Generation Study 1.

Umibecestat is an orally active BACE inhibitor with an approximately 3-fold selectivity for BACE-1 over BACE-2 and no relevant off-target binding or activity. In both animals and humans, umibecestat reduced Aβ concentrations in CSF by up to 95% [38]. The toxicology studies confirmed a benign safety profile. To date, safety and tolerability data in humans has been generated in 335 healthy participants exposed to umibecestat, including a phase IIa 3-month dose-ranging safety and tolerability study in healthy adults aged >60 years [38]. Across completed studies, the AE incidence was similar for umibecestat and placebo in subjects ≥60 years, with the exception of an imbalance of skin-related AEs observed in the 3-month study, mostly driven by pruritus (18% for umibecestat vs. 4% for placebo). The umibecestat 15 and 50 mg doses were selected based on the safety and tolerability as well as CSF Aβ-lowering results obtained in the first-in-human study and the 3-month study [39]. Although both doses achieve a substantial effect on lowering Aβ (strong and moderate), these two doses have largely nonoverlapping exposure distributions. Umibecestat is being tested in cohort 2 of Generation Study 1 and in Generation Study 2.

2.5.2. Randomization

At the baseline, participants are randomized to one of the treatment arms (Generation Study 1: cohort 1 [CAD106 450 μg plus alum 450 μg, or matching placebo] or cohort 2 [umibecestat 50 mg or matching placebo]; Generation Study 2: umibecestat 50 mg, 15 mg, or placebo) via an interactive response technology system. Generation Study 1 is stratified by age and region with 690 participants randomized in cohort 1 in a ratio 5:3 CAD106:placebo, and 650 participants in cohort 2 in a ratio of 3:2 umibecestat:placebo. Generation Study 2 randomization is stratified by age, region, genotype, and method used to determine amyloid status; 2000 participants will be randomized 2:1:2 to umibecestat 50 mg:umibecestat 15 mg:placebo.

2.5.3. Treatment schedule and duration

Cohort 1 participants in Generation Study 1 receive intramuscular injections of CAD106 with alum, or placebo with alum, at the study site every 6 weeks for the first 3 injections and then every 3 months (approximately 13 weeks) thereafter. Cohort 2 participants in Generation Study 1 and participants in Generation Study 2 receive medication supplies for 3 months of treatment with umibecestat 50 mg, umibecestat 15 mg (study 2 only), or placebo for once-daily oral intake. From the baseline visit onward, participants attend clinic visits every 3 months to receive study medication and a short safety assessment, and every 6 months for full safety and efficacy assessments (summary of assessments in Table 4).

Table 4.

Key study assessments in the treatment periods of the Generation Program

| Assessment | Every 3 months | Every 6 months | Yearly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard safety assessments | Adverse events and concomitant medications (including procedures, non-drug therapies [e.g., physical therapy, blood transfusions]), C-SSRS | Physical and neurological evaluation, laboratory tests, ECGs (also, month 3 in the first year) | – |

| Vital signs | In Generation Study 1 Cohort I (CAD106 or placebo) | In Generation Study 1, cohort II, and Generation Study 2 (umibecestat or placebo) (also, month 3 and 9 in the first year) | – |

| Imaging: MRI (including fMRI) | – | – | In both studies and cohorts (also at month 6 in the first year) |

| Imaging: FDG PET | – | – | In Generation Study 1 at baseline and year 2 |

| Imaging: Amyloid PET | – | – | In Generation Study 1, mandatory at baseline and year 2, optional at year 5. In Generation Study 2, voluntary at baseline (unless used for determination of amyloid status |

| Imaging: Tau PET | – | – | In Generation Study 1, voluntary at baseline, year 2, and year 5 In Generation Study 2, mandatory at baseline, year 2, and year 5 |

| Clinical scales | – | RBANS, Raven's Progressive Matrices, MMSE, CDR, MCI/dementia due to AD diagnostic verification, ECog | GDS, NPI-Q, Lifestyle questionnaire, Qol-AD |

| Blood samples | – | PK and Aβ plasma | Biomarker plasma/serum (Month 6, Years 1, 2, 5, PPW) |

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDR, clinical dementia rating; C-SSRS, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECog, everyday cognition scale; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; GDS, geriatric depression scale; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPI-Q, neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire; PET, positron emission tomography; PK, pharmacokinetic; PPW, premature participant withdrawal; Qol-AD, quality of life in Alzheimer's disease.

Safety assessments include standard assessments (e.g., vital signs, ECGs, laboratory tests, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale, and specific assessments related to potential central nervous system [CNS]) or other safety assessment requirements (see Table 4). Assessment of the impact from APOE genetic disclosure (and disclosure of brain amyloid status in study 2) include the Geriatric Depression Scale [39], State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults [40], and other scales such as disease-specific distress (which is a modified version of the Impact of Events scale [41]) and the REVEAL Impact of Genetic Testing for AD [42] in the 12-month follow-up in Generation Study 1 only.

Brain MRI scans for monitoring of cerebrovascular pathology and detection of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities are completed every 6 months during the first year and on an annual basis subsequently.

CSF and PET biomarker data to assess the underlying AD pathology are collected at the baseline, month 24, and month 60.

An independent Data Monitoring Committee monitors the safety, tolerability, and efficacy data with input from a dedicated Disclosure Monitoring Advisory Group focusing on assessments of impact of genotype and risk disclosure.

At each 6-month visit, the investigator assesses the participant for the presence of MCI or dementia using prespecified criteria. The core clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association Working Group are used for diagnosis of MCI or dementia [43], [44]. In addition to the diagnosis made by the investigator, an independent Progression Adjudication Committee reviews all MCI/dementia diagnoses and any case of increase in CDR global score. The adjudicated cases that are confirmed at the next 6-month efficacy visit will be considered as an event for the TTE primary endpoint.

Participants are treated for at least 60 months up to a maximum of 96 months, with treatment continuing for at least 60 months and until the target number of events for the TTE endpoint has been observed and confirmed in the respective cohort/study. Participants recruited first will be treated at least until the last participant enrolled reaches approximately month 60.

Participants who progress to MCI/dementia due to AD will continue on their assigned investigational treatment. The investigator should discontinue the investigational treatment for a given participant if, overall, he/she believes that continuation would be detrimental to the participant's well-being. In the case of progression to late-moderate or severe dementia, the participant will be discontinued from the study. Similarly, participants who progress to dementia due to a cause other than AD will be discontinued.

This long study duration is deemed necessary given the mechanisms of action of umibecestat and CAD106: no short-term benefit is expected, particularly in this preclinical stage. The minimum treatment duration of 60 months was chosen based on the likelihood of detecting (1) a sufficient number of events and (2) sufficient cognitive decline as measured by APCC test score in the placebo arm to allow the detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects. We expect that, if the investigational drug delays the underlying pathological or pathophysiological disease processes, the clinical benefit will emerge only gradually over time. As discussed in the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use Guideline [45], prevention trials require long treatment durations, typically at least 5 years.

2.6. Follow-up and end of the study

At the end of the treatment period, all participants will have a safety follow-up visit, which will be scheduled for 12 weeks after the last study drug intake or 6 months after the last injection in cohort 1 of Generation Study 1. Participants will be discharged from the study after the follow-up visit or offered to enter an open-label extension.

2.7. Sample size calculations

Sample size calculations in both studies were driven by a target power of 80% for the primary TTE endpoint at the projected time of final analysis. The expected event rate of the study population was based on the lifetime risk and risk by age group to develop MCI or dementia due to AD [46], [47] and on risk estimation based on data from longitudinal cohort studies, including the following:

-

1.

Three cohort studies of aging and dementia at the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center (Religious Orders Study, Memory and Aging Project, or the Minority Aging Research Study),

-

2.

Data from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Washington University,

-

3.

Generation Study 2 only: data from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and from the Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing.

The estimated event risk in 5 years, based on the aforementioned cohorts, was between 30% and 40%. Sample size calculation for Generation Study 1 was based on trial simulations using mathematical models for the primary endpoints. The sample size calculation for the TTE endpoint (i.e., time to first diagnosis of MCI and dementia due to AD) was based on the following assumptions for both studies:

-

1.

An observation period of 60–96 months,

-

2.

30% dropout rate over 5 years (or a yearly rate of 6.9%),

-

3.

α = 4%, two-sided test.

For the comparison of change from the baseline to month 60 on APCC in the active treatment arm versus placebo, the aforementioned sample sizes are sufficient to detect an effect size of 0.33 (Generation Study 1) and 0.20 (Generation Study 2) using a simple 2-sided t-test and a significance level of α = 1% with a power of 80%. Results from simulations indicate that using a longitudinal model and adjusting for prognostic factors will increase power to detect differences in the APCC endpoint.

Generation Study 1 (N = 1340 total participants) will have 430 participants (cohort 1) who will receive CAD106 and 260 participants who will receive matching placebo. A slight over-allocation to CAD106 was needed to account for an expected 10% of participants who will not develop a serological response. In cohort 2 of Generation Study 1, 390 participants will receive umibecestat and 260 will receive matching placebo. Generation Study 2 (N = 2000 total participants) will have 800 participants in the umibecestat 50 mg group, 400 in the umibecestat 15 mg group, and 800 in the placebo group.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The primary analysis comprises statistical tests of hypotheses on the dual primary endpoints. The statistical tests will compare each active investigational treatment/dose group versus their corresponding placebo as the control group. For both investigational drugs and doses, primary analyses will be performed on both the TTE endpoint and the APCC score. The following null hypotheses will be tested at a significance level of α = 5%, where initially 80% of the α (after adjusting for the planned interim analysis) will be allocated to the hypothesis on TTE and 20% to the APCC:

-

1.

H01: The active treatment arm does not differ from placebo with regard to the distribution of time to first diagnosis of MCI or dementia due to AD;

-

2.

H02: The active treatment arm does not differ from placebo in the mean change from the baseline to month 60 in the APCC test score.

The first hypothesis will be tested using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with treatment group as the factor of interest and adjusting for important baseline covariates (baseline APCC score, baseline amyloid load, region, and age). The second hypothesis will be tested using a mixed-effects model for repeated measurements for the change from the baseline with treatment group as the response measure of interest, visit window to model the time course (as a categorical factor), and adjusting for important covariates (baseline APCC score, baseline amyloid load, region, and age).

To control the overall familywise type I error rate in Generation Study 1, a graphical procedure for appropriate multiplicity adjustment will be applied to the analyses of the primary and the key secondary efficacy variable Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes. A Bonferroni adjustment will account for the planned interim analysis on primary endpoints. To control the overall familywise type I error rate in Generation Study 2, an appropriate multiplicity adjustment procedure using a closed testing strategy will be applied to the analyses of the primary efficacy variables; the procedure will take into account testing two endpoints, two active arms versus placebo, two stages, and the interim analysis on primary endpoints.

Secondary endpoints (Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes; Everyday Cognition Scale; individual scales included in the APCC battery such as Mini-Mental State Examination, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status indices and total scores; amyloid, tau and/or FDG PET; volumetric MRI; total tau, phosphorylated tau in CSF) will all be analyzed using longitudinal models, such as a mixed-effects model for repeated measurements similar to the approach for the primary endpoint APCC, with treatment as the main factor while adjusting for important covariates. For the secondary safety parameters (AEs, serious AEs, laboratory results, vital signs, ECG, Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale, safety brain MRI scans), pharmacokinetics of umibecestat and for Aβ-immunoglobulin G response to CAD106, descriptive statistics will be provided.

2.9. Ethics

The studies are being conducted and reported in accordance with International Conference on Harmonization Harmonized Tripartite Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and are approved by the appropriate institutional review committees and regulatory agencies.

Eligible participants may only be included in the study after providing written informed consent (witnessed, where required by law or regulation). The study partner, who provides additional information regarding the participant during the study, is also required to assent. In case of change of person in this role during the study, the new study partner is asked to assent by adding his/her signature next to his/her predecessor on the latest informed consent form signed by the participant.

3. Discussion

The Generation Program is investigating whether early treatment with either Aβ-directed therapies (umibecestat and CAD106) in cognitively unimpaired individuals at a high risk for developing symptomatic AD are suitable treatment strategies [26]. The results of these studies could change the treatment paradigm for AD, whereby individuals who are at elevated risk can be treated before clinical symptoms of MCI or dementia due to AD develop. We expect that some participants treated with placebo will progress to MCI, and a smaller number may progress to dementia during the course of the trials. We aim to demonstrate whether either or both treatments have the ability to prevent or slow the progression of AD symptoms as well as biomarker measures of AD pathology and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired participants.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria limit the study population to APOE4 HMs, or HTs with elevated brain amyloid levels. Both study populations represent individuals at a particularly elevated risk of developing symptoms of MCI or dementia due to AD. The age range was chosen to ensure that participants were at high risk for developing AD symptoms during the study duration [27]. APOE4 carriers are estimated to represent about 25 to 30% of the general population and are at higher risk of developing symptoms of late-onset AD than people who are noncarriers of the ε4 allele [46]. The ε4 allele has been associated with reduced Aβ clearance, increased Aβ accumulation, increased Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, inflammation, reduced energy metabolism, impairment in mitochondrial function, aspects of metabolism, and other processes relevant to AD risk [13]. APOE4 carriers have greater fibrillar amyloid deposition than age-matched noncarriers and accelerated age-dependent cognitive decline and the amount of amyloid deposition in preclinical AD individuals and rate of cognitive decline, respectively, are directly associated with ε4 gene dose [3].

The risk of progression to MCI due to AD or dementia due to AD increases with age [47]. HMs are at particularly high risk (∼30–55%) of developing clinical symptoms due to AD by age 85 years [33]. No further enrichment beyond genotype and age to the HM population was implemented. HTs in the age range 60-75 years have a 20-25% lifetime risk for AD by age 85 years [33]. To select a population with a comparable risk to HMs with a similar estimated progression rate within the same age range, HTs are further enriched for the presence of elevated brain amyloid at screening.

These studies will help test the amyloid hypothesis, with two different anti amyloid approaches, in the preclinical stage of AD, bringing critical evidence for the utility of earlier intervention, as compared with recent clinical trials in participants with symptomatic AD, all of which have failed to show benefit [19], [24]. Biomarker endpoints are also critical in preventative AD treatment clinical trials to identify risk with more accuracy, monitor disease progression before onset of clinical symptoms, and serve as surrogate markers for clinical research. Indeed, the design of the Generation studies allow for a full biomarker assessment at 2 and 5 years of treatment. In addition, these studies will explore whether treatment biomarker effects at month 24 predict subsequent clinical benefit at month 60 (theragnostic utility) and to examine predictive and prognostic utility of the baseline characteristics. If biomarkers are identified as surrogate markers for accelerated registration, longer term follow-up will be required to establish clinical benefits.

In concordance with principles articulated by the Collaboration for Alzheimer's Prevention [48] and our other API colleagues, the Generation Program will provide a public resource of the baseline data from its unprecedented number of cognitively unimpaired HMs and HTs (in ways that protect participant identification and trial integrity) after completion of the recruitment, helping the field to advance the study of preclinical AD. Furthermore, we will provide a public resource of trial data and available biological samples at specified times after the trials are over to further advance the study of AD and inform the design of prevention trials.

One limitation of the Generation studies is that it is possible that antiamyloid treatments, for example, BACE inhibitors, which may not clear existing plaques, or even potential plaque-clearing treatments may need to be administered before biomarker evidence of fibrillar Aβ deposition to demonstrate benefit. By studying APOE4 HMs, we have the ability to explore the differential effects of treatments in individuals with and without elevated brain amyloid because it is expected that nearly one-third of HMs in the selected age range will enroll without elevated amyloid at the baseline, which could help explore the predictive value of earlier stage disease. Even if we may not have the power to detect effects on cognitive or clinical endpoints, treatment effects may be detectable particularly on biomarkers. In addition, while we have introduced a number of strategies to maximize our power to detect treatment effects based on our cognitive and/or clinical endpoints, it remains possible that we will not have sufficient power to detect more modest effects. Studies such as those in the Generation Program, those in other API, A4 and DIAN programs, and other future prevention trials may provide the best way to find out [23].

Another limitation of the Generation Program is whether the APOE4 results could be generalized and applicable to persons with preclinical AD who do not carry an APOE4 allele. Because amyloid-targeted therapies are expected to reduce and prevent amyloid plaque accumulation independent of the multiple potential causes of amyloid deposition in late-onset AD, results might be generalizable and applicable to preclinical AD beyond APOE4 carriage. It is also possible that such subjects (APOE4 carriers) might be less responsive to treatment (e.g., that rapid amyloid deposition and faster clinical progression could be a negative predictor of response).

4. Conclusion

The Generation Program is designed to assess the efficacy, safety, and biomarker effects of the two treatments in individuals at high risk for AD. It will also provide a plausible test of the amyloid hypothesis, thus helping to accelerate the evaluation of AD prevention therapies.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: We used sources such as PubMed to review the literature on Alzheimer's disease (AD) and clinical trials of antiamyloid medications.

-

2.

Interpretation: The Generation Program will investigate whether early treatment with amyloid beta (Aβ)-directed therapies (umibecestat, an orally available β-site-amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme-1 inhibitor, and CAD106, an active, second-generation Aβ immunotherapy) in cognitively unimpaired individuals at a high risk for developing symptomatic AD are suitable treatment strategies. We aim to demonstrate whether either or both treatments have the ability to prevent or slow the progression of AD symptoms as well as biomarker measures of AD pathology and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired participants.

-

3.

Future directions: The results of these studies could change the treatment paradigm for AD, whereby individuals who are at elevated risk can be treated before clinical symptoms of mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to AD develop.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Laura Jakimovich and Trisha Walsh for their critical contributions to this program, and the Treatment Selection Advisory Committee: Paul Aisen, M.D.; Steven DeKosky, M.D.; David Holtzman, M.D.; Frank LaFerla, Ph.D.; Lon S. Schneider, M.D. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the Data Monitoring Committee, the Progression Adjudication Committee, and the Data Monitoring Advisory Group. The authors thank Jackie L. Johnson, PhD, of Novartis Ireland Ltd for providing medical writing support/editorial support, which was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

This Generation Program is funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland, and Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, in collaboration with the Banner Alzheimer's Institute located in Phoenix, AZ, USA. Generation Study 1 is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging (1UF1AG0461501), part of the National Institutes of Health, as well as the Alzheimer's Association, FBRI, GHR Foundation and Banner Alzheimer's Foundation.

Trial registration: Generation Study 1 (NCT02565511) and Generation Study 2 (NCT03131453).

Authors' contributions: All authors participated in the study design, implementation, and/or conduct of the Generation studies. All authors contributed to the review of the protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Cristina Lopez Lopez, Angelika Caputo, Fonda Liu, Marie-Emmanuelle Riviere, Marie-Laure Rouzade Dominguez, Martin Zalesak, J. Michael Ryan, and Ana Graf are the full or former employees of and shareholders in Novartis Pharma AG/ Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Cristina Lopez Lopez is a named inventor on international patent application nos. PCT/IB2017/054307 and PCT/IB2017/056281, both of which are assigned to Novartis AG. Pierre N. Tariot obtained grants from Novartis, Amgen, National Institute of Aging (RF1 AG041705-01A1, UF1 AG046150, R01 AG055444, 1R01AG058468), and Genentech/Roche; research support from National Institute on Aging, Arizona Department of Health Services, Alzheimer's Association, Banner Alzheimer's Foundation, FBRI, GHR, Nomis Foundation, and the Flinn Foundation; consultant fees from Acadia, Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, AC Immune, Auspex, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Brain Test Inc., California Pacific Medical Center, Chase Pharmaceuticals, CME Inc., GliaCure, Insys Therapeutics, Pfizer, and T3D; consulting fees and research support from AstraZeneca, Avanir, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck & Co., Roche, and Takeda; research support only from Amgen, Avid, Biogen, Elan, Functional Neuromodulation [f(nm)], GE, Genentech, Novartis, and Targacept; and stock options in Adamas Pharmaceuticals. Jessica B. Langbaum received research support from National Institute on Aging (RF1 AG041705-01A1, UF1 AG046150), Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Amgen, Banner Alzheimer's Foundation, FBRI, GHR, Nomis Foundation, and Alzheimer's Association; and consulting fees from Biogen and Lilly. Carolyn Langlois is an employee of Banner Alzheimer's Institute. Ronald G. Thomas obtained research support from National Institutes of Health (U01 AG010483) and consultant fees from Toyama and vTv. Vissia Viglietta and Rob Lenz are employees and shareholders of Amgen. Eric M. Reiman obtained research support from National Institute on Aging (RF1 AG041705-01A1, UF1 AG046150, R01 AG031581, R01 AG055444, P30 AG19610), Novartis, Amgen, Banner Alzheimer's Foundation, Alzheimer's Association, GHR Foundation, F-Prime Biosciences Research Initiative, and NOMIS Foundation; consultant fees from Alkahest, Alzheon, Axovant, Biogen, Denali, Pfizer, United Neuroscience, and Zinfandel Pharma; patent to Banner Health (US Patent No. 9,492,114).

References

- 1.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apter J.T., Shastri K., Pizano K. Update on Disease-Modifying/Preventive Therapies in Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2015;4:312–317. doi: 10.1007/s13670-015-0141-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McEvoy L.K., Brewer J.B. Biomarkers for the clinical evaluation of the cognitively impaired elderly: Amyloid is not enough. Imaging Med. 2012;4:343–357. doi: 10.2217/iim.12.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiman E.M., Chen K., Liu X., Bandy D., Yu M., Lee W. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiman E.M., Chen K., Alexander G.E., Caselli R.J., Bandy D., Osborne D. Correlations between apolipoprotein E epsilon4 gene dose and brain-imaging measurements of regional hypometabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8299–8302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiman E.M., Chen K., Alexander G.E., Caselli R.J., Bandy D., Osborne D. Functional brain abnormalities in young adults at genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer's dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:284–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2635903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiman E.M., Caselli R.J., Yun L.S., Chen K., Bandy D., Minoshima S. Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer's disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:752–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiman E.M., Caselli R.J., Chen K., Alexander G.E., Bandy D., Frost J. Declining brain activity in cognitively normal apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 heterozygotes: A foundation for using positron emission tomography to efficiently test treatments to prevent Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3334–3339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061509598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleisher A.S., Chen K., Quiroz Y.T., Jakimovich L.J., Gutierrez Gomez M., Langois C.M. Associations between biomarkers and age in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease kindred: A cross-sectional study. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:316–324. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonham L.W., Geier E.G., Fan C.C., Leong J.K., Besser L., Kukull W.A. Age-dependent effects of APOE epsilon4 in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:668–677. doi: 10.1002/acn3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen W.J., Ossenkoppele R., Knol D.L., Tijms B.M., Scheltens P., Verhey F.R. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:1924–1938. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selkoe D.J., Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C.C., Liu C.C., Kanekiyo T., Xu H., Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doody R.S., Thomas R.G., Farlow M., Iwatsubo T., Vellas B., Joffe S. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes C., Boche D., Wilkinson D., Yadegarfar G., Hopkins V., Bayer A. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: Follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salloway S., Sperling R., Gilman S., Fox N.C., Blennow K., Raskind M. A phase 2 multiple ascending dose trial of bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:2061–2070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevigny J., Chiao P., Bussiere T., Weinreb P.H., Williams L., Maier M. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;537:50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salloway S., Sperling R., Fox N.C., Blennow K., Klunk W., Raskind M. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egan M.F., Kost J., Tariot P.N., Aisen P.S., Cummings J.L., Vellas B. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiman E.M., Langbaum J.B., Tariot P.N. Alzheimer's prevention initiative: A proposal to evaluate presymptomatic treatments as quickly as possible. Biomark Med. 2010;4:3–14. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiman E.M., Langbaum J.B., Fleisher A.S., Caselli R.J., Chen K., Ayutyanont N. Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative: A plan to accelerate the evaluation of presymptomatic treatments. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:321–329. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiman E.M., Langbaum J.B., Tariot P.N., Lopera F., Bateman R.J., Morris J.C. CAP--advancing the evaluation of preclinical Alzheimer disease treatments. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langbaum J.B., Fleisher A.S., Chen K., Ayutyanont N., Lopera F., Quiroz Y.T. Ushering in the study and treatment of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:371–381. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honig L.S., Vellas B., Woodward M., Boada M., Bullock R., Borrie M. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tariot P.N., Lopera F., Langbaum J.B., Thomas R.G., Hendrix S., Schneider L.S. The Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative Autosomal-Dominant Alzheimer's Disease Trial: A study of crenezumab versus placebo in preclinical PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers to evaluate efficacy and safety in the treatment of autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease, including a placebo-treated noncarrier cohort. Alzheimer's Demen Translational Res Clin Interventions. 2018;4:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez Lopez C., Caputo A., Liu F., Riviere M.E., Rouzade-Dominguez M.L., Thomas R.G. The Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative Generation Program: Evaluating CNP520 Efficacy in the Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4:242–246. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2017.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan A.W., Tetzlaff J.M., Gotzsche P.C., Altman D.G., Mann H., Berlin J.A. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan A.W., Tetzlaff J.M., Altman D.G., Dickersin K., Moher D. SPIRIT 2013: New guidance for content of clinical trial protocols. Lancet. 2013;381:91–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes C.P., Berg L., Danziger W.L., Coben L.A., Martin R.L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Randolph C., Tierney M.C., Mohr E., Chase T.N. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:310–319. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farias S.T., Mungas D., Reed B.R., Cahn-Weiner D., Jagust W., Baynes K. The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): Scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:531–544. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posner K., Brown G.K., Stanley B., Brent D.A., Yershova K.V., Oquendo M.A. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian J., Wolters F.J., Beiser A., Haan M., Ikram M.A., Karlawish J. APOE-related risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia for prevention trials: An analysis of four cohorts. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winblad B., Andreasen N., Minthon L., Floesser A., Imbert G., Dumortier T. Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:597–604. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiessner C., Wiederhold K.H., Tissot A.C., Frey P., Danner S., Jacobson L.H. The second-generation active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 reduces amyloid accumulation in APP transgenic mice while minimizing potential side effects. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9323–9331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0293-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandenberghe R., Riviere M.E., Caputo A., Sovago J., Maguire R.P., Farlow M. Active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 in Alzheimer's disease: A phase 2b study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farlow M.R., Andreasen N., Riviere M.E., Vostiar I., Vitaliti A., Sovago J. Long-term treatment with active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in mild Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumann U., Ufer M., Jacobson L.H., Rouzade-Dominguez M.L., Huledal G., Kolly C. The BACE-1 inhibitor CNP520 for prevention trials in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809316. pii: e9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reisberg B., Ferris S.H., de Leon M.J., Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spielberger C., Gorsuch R., Lushene R., Vagg P., Jacobs G. Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horowitz M., Wilner N., Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung W.W., Chen C.A., Cupples L.A., Roberts J.S., Hiraki S.C., Nair A.K. A new scale measuring psychologic impact of genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:50–56. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318188429e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Medicines Agency . 2018. Guideline on the clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease-revision-2_en.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jansen W.J., Ossenkoppele R., Visser P.J. Amyloid Pathology, Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer Disease Risk--Reply. JAMA. 2015;314:1177–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Genin E., Hannequin D., Wallon D., Sleegers K., Hiltunen M., Combarros O. APOE and Alzheimer disease: A major gene with semi-dominant inheritance. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:903–907. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weninger S., Carrillo M.C., Dunn B., Aisen P.S., Bateman R.J., Kotz J.D. Collaboration for Alzheimer’s Prevention: Principles to guide data and sample sharing in preclinical Alzheimer's disease trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:631–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]