Abstract

This is a case of emphysematous cystitis with a rare complication of bladder rupture requiring surgical intervention in a diabetic man who presented with urinary retention and abdominal pain, with a large amount of intraperitoneal free air on computed tomography scan.

Keywords: Emphysematous cystitis, Bladder rupture, Pneumoperitoneum

Introduction

Gas-producing infections in the urinary tract are rare, and manifest as emphysematous cystitis in the urinary bladder, emphysematous pyelitis and ureteritis in the collecting system, and emphysematous pyelonephritis in the kidney parenchyma.1,2 Case reports of emphysematous cystitis describe Escherichia coli as the most frequent causative pathogen.1 Other culprit organisms include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Candida albicans.1 The disease most commonly occurs in diabetic female patients; other risk factors include immunosuppression, recurrent urinary tract infections, neurogenic bladder, indwelling catheter, and bladder outlet obstruction.2 While many patients improve with conservative management, a small number will require urgent surgical intervention.2

Case report

A 60-year-old man with benign prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes mellitus type 2 with a hemoglobin A1c of 7.8, and a history of urinary tract infections presented to the emergency department with one week of abdominal pain, gross hematuria, and difficulty voiding. Over the 24 hours prior to presentation he developed worsening pain, pneumaturia, and acute urinary retention. In the emergency department the patient was tachycardic, normotensive, and febrile to 102 °F. On physical exam he had rigors, abdominal guarding and rebound tenderness, including suprapubic tenderness. Bedside bladder scan showed a volume of 50 cc. Initial labs were significant for a lactic acid of 3.4 mMol/L, white blood cell count of 7.9 K/μL, hemoglobin of 8.9 g/dL, serum sodium of 132 mEq/L, and creatinine of 2.27 mg/dL. His urinalysis demonstrated 11–50 WBC/hpf, >100 RBC/hpf, positive nitrates, and moderate leukocyte esterase.

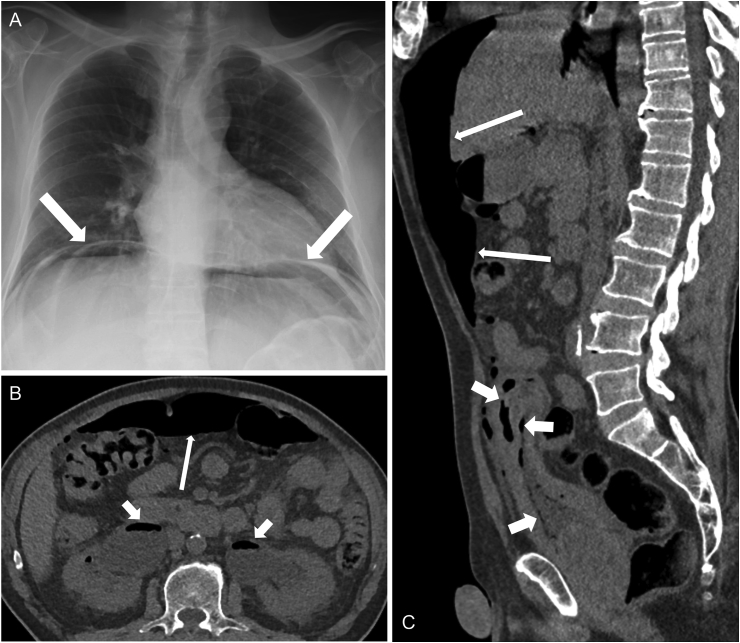

An upright chest x-ray was obtained given the concern for perforated viscus. This was notable for free air under the diaphragm (Fig. 1a). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed extensive pneumoperitoneum, emphysematous cystitis, bilateral hydronephrosis, emphysematous pyelitis, and a possible abscess near the dome of the bladder (Fig. 1b and c).

Fig. 1.

(A) Portable chest radiograph shows a large amount of free air beneath the diaphragm. (B) Axial non-contrast CT shows a large amount of intraperitoneal free air (long arrow) and air within bilateral dilated collecting systems (short arrows). (C) Sagittal non-contrast CT shows a large amount of intraperitoneal free air (long arrows), and air within the bladder wall, bladder lumen, and in the necrotic dome of the bladder (short arrows).

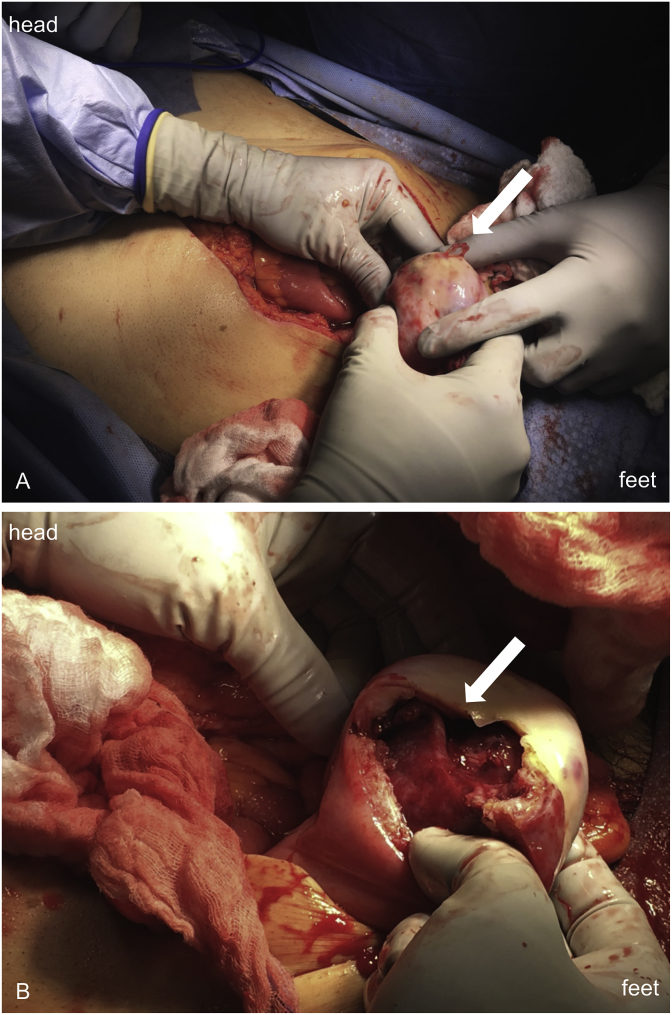

Due to the large amount of free air, there was a high suspicion for a bowel perforation. Additionally, given the radiographic appearance of the bladder, the differential also included an enterovesical fistula or possible bladder perforation. General surgery and urology were consulted. Intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered, and the patient was taken urgently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy and cystoscopy. Upon entering the peritoneum, a significant amount of cloudy free fluid was encountered, which was sent for culture. A full examination of the bowel failed to identify any evidence of a perforation. Attention was then turned to the bladder. The intraperitoneal portion of the bladder was grossly abnormal, appearing fibrotic and devitalized. A small 3–4 mm defect was identified at the bladder dome within a large area of necrosis (Fig. 2a). Concurrent cystoscopy confirmed the bladder perforation and revealed diffuse inflammation, trabeculations, and diverticula. A partial cystectomy was performed with removal of a 7 × 5 cm segment of necrotic bladder tissue notable for several discrete abscess pockets (Fig. 2b). The bladder edges were debrided to healthy tissue, a suprapubic catheter and urethral catheter were placed, and the bladder was closed in two layers. The abdomen was copiously irrigated. Post-operatively the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for sepsis management. His lactic acidosis resolved, and he remained hemodynamically stable. He was ultimately discharged on postoperative day four on a two-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. He has since failed voiding trials and is scheduled for a transurethral resection of the prostate. Urine and intra-abdominal cultures grew Escherichia coli. Final pathology revealed focal transmural necrosis, acute and chronic inflammation with intramural abscess, and serositis with fibrosis.

Fig. 2.

(A) Thick necrotic rind apparent at bladder dome. A small defect was noted to be extravasating fluid when the bladder was compressed (white arrow). (B) Cystotomy subsequently revealed necrotic tissue with several abscess pockets white arrow.

Discussion

The diagnosis of emphysematous cystitis is usually made with plain abdominal radiographs or CT, as patients often present with vague symptoms such as abdominal pain, and typical urinary tract infection symptoms occur in only 50% of cases.1,2 Air is seen within the bladder wall, and intravesical air can make the bladder wall appear like a “beaded necklace” on CT due to thickening from submucosal blebs.3 In uncomplicated cases, emphysematous cystitis is managed conservatively with antibiotics and urinary drainage. In roughly 10% of cases, surgical intervention is required and can consist of total or partial cystectomy.2 Overall mortality rates are reported to be 7–9%.2 Bladder rupture in the setting of emphysematous cystitis is a rare occurrence, with only a handful of cases reported in the literature demonstrating small amounts of intraperitoneal free air.4,5 However, the large volume of free air caused by this case of ruptured emphysematous cystitis is more consistent with the level seen in instances of bowel perforation. The patient's urinary retention was likely a significant contributing factor to the course of his disease.

Conclusion

The consequences of bladder rupture from emphysematous cystitis can be devastating if unrecognized. In the appropriate clinical context there must be a high index of suspicion for bladder perforation, and early urologic consultation for surgical intervention should be pursued.

Declarations of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Matthew T. Hudnall, Email: matthew.hudnall@northwestern.edu.

Brian J. Jordan, Email: brian.jordan@northwestern.edu.

Jeanne Horowitz, Email: jeanne.horowitz@nm.org.

Stephanie Kielb, Email: stephanie.kielb@nm.org.

References

- 1.Grupper M., Kravtsov A., Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis. Medicine. 2007;86:47–53. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas A.A., Lane B.R., Thomas A.Z. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int. 2007;100:17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grayson D.E., Abbott R.M., Levy A.D. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2002;22:543–561. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma06543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viswanathan S., Rajan R.P., Iqbal N. Enterococcus faecium related emphysematous cystitis and bladder rupture. Australas Med J. 2012;5:581–584. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2012.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roels P., Decaestecker K., De Visschere P. Spontaneous bladder wall rupture due to emphysematous cystitis. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2016;100:83. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]