Abstract

Bioinspired self-healing materials are being developed with intrinsic or extrinsic mechanisms. Some materials heal by an external stimulus, such as heat, UV light, pH, electric field and humidity. Hydrogels are among the commonly used materials, which can self-heal by application of an external stimulus. In this study, a self-healing polyacrylamide hydrogel was selected which is known to swell when exposed to water and heal. Silica nanoparticles were added to the hydrogel and a fluorosilane overcoat was used to produce a superliquiphobic surface with a low tilt angle and self-cleaning properties. A fused titania coating on the glass substrate was used to promote adhesion to hydrogel coatings. Hydrogel-based coatings exhibited the ability to repel water and oil, anti-icing properties down to −60°C, self-cleaning, the ability to maintain superliquiphobicity in hot environments up to about 95°C and high wear resistance. The hydrogel-based coating also demonstrated self-healing capability after hydration of a scratched surface.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Bioinspired materials and surfaces for green science and technology (part 2)’.

Keywords: superoleophobic, self-healing, hydrogel, nanoparticles, fluorination, wear resistance

1. Introduction

Species found in living nature self-heal. Self-healing, self-repair and self-recovery are used synonymously. Self-healing refers to a material's ability to self-heal damage and regain its associated properties. It requires the spontaneous formation of new bonds when old are broken within the material. Self-healing may occur by intrinsic or extrinsic mechanisms [1–3]. In the intrinsic mechanisms, self-healing materials consist of autonomous self-healing capabilities, which are defined as the property that enables a material to intrinsically and automatically heal damage, without the intervention of an external stimulus. It is generally related to chemical structure. For example, the polymer chains may temporarily increase mobility and flow to the damaged area or broken chemical bonds are repaired [4]. In the extrinsic mechanisms, self-healing occurs by chemical changes caused by an external stimulus.

Table 1 provides a review of representative self-healing literature classified as autonomous or based on external stimuli. Autonomous self-healing includes chemical reaction, bio-healing, self-sealing and capsulated healing agents. As an example of a chemical reaction, hydrogels can heal themselves by dynamic disulfide exchange reaction or hydrogen bonding [5,6]. The bio-healing ability of concrete can be provided by bacteria, which produces calcium carbonate crystals and fills cracks [2,7]. Self-sealing can be provided by a chemical reaction between carbon dioxide dissolved in rainfall and particles of dried cement which prolong the service life of concrete infrastructure [8]. Capsules incorporated in bulk material can provide healing reagents when the material is cracked [2,9].

Table 1.

Literature review of self-healing materials with their mechanisms.

| approach/stimulus | material | mechanism | comments | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| autonomous | ||||

| chemical reaction | poly(HEAA-co-META) hydrogel coating | the dynamic disulfide exchange reaction | cracked polymer coating self-heals based on disulfide exchange reaction | Yang et al. [5] |

| hydrogels | hydrogen bonding | hydrogen bonds | Taylor and in het Panhius [6] | |

| bio-healing | cracked concrete and calcium carbonate | bacteria produce calcium carbonate crystals as a byproduct in concrete | internal, limited self-healing | Jonkers [7] |

| self-sealing | carbon dioxide dissolved in rainfall, dried cement | the chemical reaction of calcium carbonate formation | prolong the service life of infrastructure | Li and Yang [8] |

| capsules | capsulated healing reagents | capsules are included in bulk material and provide healing reagents when the material is cracked | limitation in number of self-healing cycles | Dissendruck et al. [9] |

| external stimulus | ||||

| heat | C3 symmetric hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene | temperature-induced re-arrangement of organic semiconductor material | when the organic material is deposited on the substrate, re-arrangement helps to achieve dislocation free homogeneous surface of the semiconductor layer | Treossi et al. [10] |

| asphalt | bitumen flows and drains into cracks by temperature-dependent viscosity | to trigger and enhance the self-healing of asphalt | Grossegger et al. [11] | |

| UV light | trithiocarbonate polymer gels | UV photoresponsive reshuffling | macroscopic self-healing of covalently cross-linked polymers in the bulk state under photostimulation | Amamoto et al. [12] |

| pH | cationic, FeIII:DOPA–chitosan hydrogels | reversible nature of the coordination bond and the gel's viscoelastic behaviour | increasing pH from acidic to basic restores storage modulus | Krogsgaard et al. [13] |

| A6ACA hydrogels | separated hydrogels are able to reheal upon reintroduction into a low-pH environment | deprotonated cylindrical hydrogels at pH 7.4 heal in low-pH solution (pH ≤3) | Phadke et al. [14] | |

| AC electrophoretic response | dextran sulfate hydrogel | AC electrophoretic adhesion of hydrogel using oppositely charged water-soluble polymers as a binder for building three-dimensional hydrogel constructs | electric field was applied with a square wave 5000 V m−1 and 0.25 Hz | Asoh et al. [15] |

| humidity | hydrogel coating by polyacrylamide solution | self-healing effect by expansion to moisture | Kim and Kim [16] | |

The external stimuli include heat, UV light, pH, AC electrophoretic response and humidity. Microdefects and dislocations in the crystalline structure can be repaired by heating [10]. Bitumen flow and draining into cracks because of a decrease in viscosity caused by heat can provide self-healing of asphalt [11]. UV light stimuli can be used to cross-link some polymers [12]. The reversible nature of the coordination bonds in pH-responsive chitosan hydrogels can restore storage modulus by increasing pH from acidic to weak alkaline [13]. Deprotonated cylindrical hydrogels at pH 7.4 can heal in low-pH solution [14]. Dextran sulfate hydrogels molecularly suture together by AC electrophoretic adhesion [15]. Swelling behaviour of acrylamide hydrogel leads to the healing of scratches and cracks when they are exposed to humidity [16].

Based on the literature review, two bioinspired approaches are prevalent, shown in figure 1. The first one includes a microencapsulated healing reagent included in bulk material, which provides healing reagents when the material is cracked (figure 1). The second approach uses an external stimulus applied to heal damage.

Figure 1.

Schematic of two approaches to fabricate self-healing coatings, (a) microencapsulated healing agent which gets ruptured by crack and provides healing, and (b) external stimuli-sensitive materials. Some polymers may be healed by heat, UV light, pH, electric field or humidity; an example may be hydrogel which swells in water (Adapted from [3]). (Online version in colour.)

Hydrogels are commonly used materials, which are known to heal by an external stimulus (table 1). The term gel, originating from gelatin, refers to a jelly-like material that can have properties ranging from soft and weak to hard and tough [17]. A polymeric hydrogel is a three-dimensionally cross-linked network of flexible polymer chains that contain water. A three-dimensional solid results from the hydrophilic polymer chains being held together by cross-links via chemical and physical bonds. Hydrogen bonding, ionic and hydrophobic interactions exist in hydrogel networks. They are water insoluble due to chemical or physical cross-linking. Owing to high hydrophilicity, the hydrogels can absorb large quantities of water. The network is able to retain the liquids, forming a swollen gel phase. Water plays an important role in determining the physico-chemical properties of the hydrogels. The number of linkages and strength (type) of moieties used in the linkages determine the degree of self-healing ability, the stability of hydrogel formation and the mechanical properties of the hydrogel [6,18]. Hydrogels may display reversible sol–gel transitions, which are induced by changes in the environmental conditions such as humidity, temperature, pH, ionic strength and wavelength of light. These are known as stimuli responsive, smart or intelligent hydrogels.

A large number of synthetic hydrogels with cross-linked networks of polymers are available. Poly(acrylic acid) and its derivatives, poly(ethylene oxide) and its copolymers, poly(vinyl alcohol), poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) and polypeptides are the main class of synthetic hydrogels [18]. The structural properties of hydrogels make them useful for various soft robotics, biomedical applications and tissue engineering, such as sensors, contact lenses, artificial organs and drug delivery systems [6,18–22].

In this study, cross-linked polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel was selected as a binder material to fabricate self-healing superliquiphobic coatings. It was selected as it has been known to be self-healing. It swells after exposure to humidity. Cast hydrogels are hydrophilic. The casting of hydrogels leads to poor adhesion due to residual stresses in the thin layer of the hydrogel in the process of dehydration. Anodized titania layer can form nanotubes and resulting roughness is known to promote adhesion [23,24]. Titania layer deposited from TiCl4 solution followed by annealing has been reported to provide strong adhesion with the glass and the overcoat in solar cells [25]. Therefore, to promote hydrogel adhesion to the glass substrate, titania coating on the glass substrate was selected. Nanoparticles were added to the hydrogel solution to develop a superhydrophobic surface. An overcoat of fluorosilane was used to produce a superliquiphobic surface. Their mechanical durability was measured by wear and scratch tests. The wear performance was compared with methylphenyl silicone with silica nanoparticles and a fluorosilane coating commonly used for superliquiphobic surfaces. The self-healing capabilities of hydrogel coatings after scratching with a knife followed by hydration with water were also tested. The results of this study are the subject of this paper.

2. Experimental details

In this section, the fabrication technique of the self-healing hydrogel coating is presented. Next, various characterization techniques which include surface morphology, wettability, self-cleaning, icephobicity, high-temperature durability and wear resistance are discussed.

(a). Fabrication method

Coatings consisting of 7 nm diameter hydrophilic SiO2 nanoparticles and a binder of cross-linked PAAm hydrogel were used to fabricate superhydrophobic surfaces. A low surface-energy fluorosilane coating was applied to obtain superoleophobic properties. SiO2 nanoparticles were selected because they have high hardness for wear resistance. Hydrophilic nanoparticles were selected to enhance chemical bonding with the water-based acrylamide monomer network. The binder completely covered nanoparticles and in spite of the use of hydrophilic nanoparticles, superhydrophobicity was achieved. To minimize agglomeration of nanoparticles in the viscous hydrogel, particle-to-binder was kept low. A fused titania coating was used as an underlayer to promote adhesion. Various fabrication steps to prepare coatings with various wettability are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of fabrication steps for superhydrophobic surfaces by depositing nanoparticles and polyacrylamide hydrogel to provide nanoroughness, followed by adding ultraviolet-ozone treatment to activate the surface and then fluorosilane to create superoleophobic surfaces. (Online version in colour.)

(i). Fused titania coating on a glass substrate

Figure 3a shows the fabrication steps. First, 1.8 ml of 99% TiCl4 solution (TiCl4 Reagent Plus, Sigma-Aldrich) was slowly dropped over 50 g ice and then diluted with 250 ml DI water (deionized water) at room temperature. Next, the glass sample was placed into the solution on a hot plate, at 70°C for 30 min. The sample was then rinsed with DI water and blow-dried in the air at room temperature. After the sample was dried, it was annealed in the oven at 550°C for 30 min [25].

Figure 3.

(a) Fabrication steps of fused titania coating (b) and the chemical structure of polyacrylamide hydrogel.

(ii). Hydrogel coating

Hydrogel coating was deposited on fused titania-coated glass using a PAAm hydrogel solution. Various steps used to prepare the PAAm solution are shown in figure 3b. First, ammonium persulfate powder [(NH4)2S2O8, assay greater than or equal to 98.0%, Sigma-Aldrich] (persulfate) was dissolved in deionized (DI) water in a 1 : 9 weight ratio. The persulfate solution acted as the initiator. A 10 µl of persulfate solution was mixed with 2.25 µl of N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide solution (C7H10N2O2, 2% in ultra-pure water, Sigma-Aldrich) (bisacrylamide) used as the cross-linker. Next, 750 µl of acrylamide solution (C3H5NO, 40% solid in ultra-pure water, Sigma-Aldrich), used as the monomer, mixed in a 1 : 1 volume ratio with DI water was added. The hydrogel solution was transformed into a gel by adding 4 µl of catalyst, which was an N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) solution (C6H16N2, assay approximately 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.). The TEMED solution, which was a tertiary amine base, helped generate free radicals from the ammonium persulfate, which in turn helped polymerize the acrylamide and bisacrylamide, thus forming a gel matrix of PAAm. High concentration of TEMED helped form a uniform gel-like state [16].

The hydrogel was then deposited onto the glass substrate and pressed by a glass plate to form a thin hydrogel coating. The top glass plate was detached after several minutes. The hydrogel coating was dehydrated in a 40 mTorr vacuum overnight.

(iii). Nanoparticle-hydrogel coating

For a composite coating with hydrogel and nanoparticles, nanoparticles were also added in the hydrogel solution before adding TEMED. For the coating mixture, 40 mg of hydrophilic silica nanoparticles (7 nm in diameter, Aerosil 380) were mechanically dispersed in about 760 µl of hydrogel solution. This resulted in a particle-to-binder ratio of about 0.25. The resulting mixture was transformed into a gel-type state adding 4 µl of the TEMED solution and casting on a glass substrate previously coated by fused titania and dried in the vacuum pressure of 40 mTorr overnight.

For a superliquiphobic coating, hydrogel composite coating was activated with ultraviolet-ozone (UVO) irradiation. Then, a fluorosilane coating was deposited. For fluorosilane deposition, one drop of trichloro(1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluoroctyl)silane (448931, Sigma-Aldrich) was vapour deposited on the sample using a closed container. The sample was attached to the top of the container via double-sided sticky tape with the surface facing down, and the droplet was placed on the bottom of the container. The set-up allowed the fluorosilane gas to uniformly coat the sample. A vapour deposition time of 60 min was used [3].

(b). Characterization techniques

(i). Surface morphology

For surface morphology measurements, an optical microscope (Nikon Optiphot-2) in the dark-field mode was used [26,27].

(ii). Wettability

Apparent contact angle and tilt angle data were measured using a standard automated goniometer (Model 290, Ramé-Hart Inc.) with 5 µl DI water and hexadecane droplets (with a diameter of a spherical droplet of about 2 mm) deposited onto the samples using a microsyringe. Contact angle was measured by taking a static profile image of the liquid–air interface and was analysed using the DROPimage software. Tilt angle refers to the angle when the droplet just began to roll off the sample surface. Contact and tilt angles were averaged over at least five measurements on different areas of the sample and were reported with mean ± σ [3].

(iii). Self-cleaning

The self-cleaning properties were examined by contaminating the sample with silicon carbide particles. Silicon carbide (SiC, Sigma-Aldrich) particles of size 10–15 µm were dispersed in a glass chamber (0.3 m diameter and 0.6 m high) by blowing 1 g of SiC powder for 10 s at 300 kPa. After dispersion, the particles were allowed to settle on the sample mounted on a 45° tilted stage for 30 min. The contaminated sample was then secured on a stage tilted at 10°, and water droplets (total volume of 5 ml) were dropped onto the surface from a height of 1 cm. The samples were imaged before and after the contamination tests. The ability for the water droplets to remove particles was quantified using image analysis software (SPIP 5.1.11, Image Metrology A/S, Horshølm, Denmark) [3].

(iv). Icephobicity

Anti-icing behaviour refers to the ability of a surface to prevent water from freezing on the surface. In automotive and aerospace applications, the automobiles and aircraft can be exposed to temperatures as low as −60°C in winter months. In this study, tests were performed on samples stored at a low temperature of −60°C. For icephobicity characterization, roll-off adhesion behaviour of supercooled water droplets (−18°C) on frozen surfaces at −60°C was carried out.

To study the roll-off adhesion behaviour of supercooled water droplets on frozen superliquiphobic surfaces, samples were placed on an inclined aluminium block with a 10° slope in a styrofoam container at −60°C. To achieve −60°C, dry ice pellets were used. The inclined aluminium block was placed inside a box containing dry ice pellets. To realize supercooled water, DI water in a sealed container was placed in the freezer at −18°C. After approximately 2 h, the DI water had not frozen, meaning it was supercooled. Supercooled water droplets with 0.5–2 mm diameter were dropped onto surfaces, and the surfaces were photographed.

(v). High-temperature durability

Temperatures up to 80°C can be encountered inside automobiles exposed to hot ambient in summer months [28,29]. The 80°C temperature is lower than the glass transition temperature of acrylamide hydrogel (97°C) [30]. Tests were performed up to a maximum temperature of 95°C.

Wettability of the coating at high temperature was examined by measuring contact angles of hot droplets on a hot sample. A beaker containing water or hexadecane and coated samples was placed individually on the hot plate. Temperatures were recorded using a digital thermometer placed in the beaker. The digital thermometer did not touch the sides of the beaker, and the liquid in the beaker was constantly stirred. Using a dropper, a droplet of liquid from the beaker was placed on the sample for about 1 min. An image of the droplet was taken, and apparent contact angle wear was calculated.

(vi). Wear test

Wear tests were performed using a ball-on-flat tribometer [26]. A 3 mm diameter sapphire ball was fixed in a stationary holder. The ball was slid on the sample at a normal load of 10 and 50 mN and the test was performed in a reciprocating motion for 100 cycles. Stroke length was 6 mm with an average linear speed of 1 mm s−1. The surface was imaged before and after the experiment using an optical microscope with a camera (Nikon Optihot-2) [3]. Wear performance of the hydrogel-based coatings was compared with commonly used methylphenyl silicone-based superliquiphobic coatings.

To further investigate the effect of any wear damage on the wettability, water tilt angles were measured before and after the wear experiments. The water droplets were dragged over the wear track to examine for any impediment of the motion of the droplet. In another measurement, the surface was tilted in order for the droplet to roll over the wear track and any increase in the tilt angle was measured. In a third measurement, the droplet was deposited directly onto the wear track and the surface was tilted to measure any increase in the tilt angle or pinning of the droplet [31].

(vii). Scratch test

To impart significant damage, scratch tests were performed using a knife. A replaceable super sharp #11 blade with a mass of 16 g was used to scratch the coating, and a 3 mm long scratch was produced on hydrogel coatings. To demonstrate self-healing, scratched coatings were hydrated with water by placing water droplets directly on the cut. After evaporation of the water, optical images were taken and compared with the ones before the hydration. The data were compared with methylphenyl silicone resin coating.

3. Results and discussion

Surface morphology, wettability, self-cleaning, icephobicity, high-temperature durability and wear resistance data of the coatings are presented. The coatings were deposited on glass.

(a). Surface morphology

The optical micrographs of hydrophilic fused titania, hydrophilic hydrogel and superliquiphobic hydrogel + NP + fluorosilane are shown in figure 4. The lateral size of surface asperities is in the order of a couple of microns. It is important to have surface features less than the size of the liquid droplets to allow the formation of air pockets desired for superliquiphobicity [3].

Figure 4.

Optical micrographs of hydrophilic fused titania, hydrophilic hydrogel and superliquiphobic hydrogel + NP + fluorosilane on glass. The lateral size of surface asperities is in the order of 5 µm. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Wettability

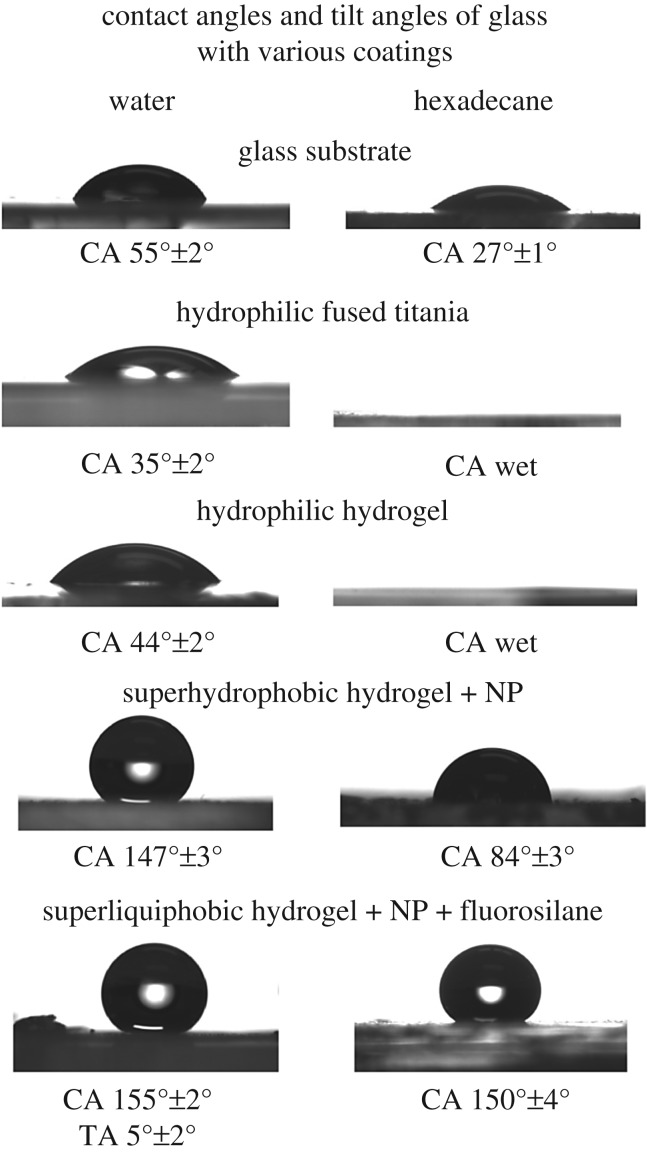

Figure 5 presents contact angle data of samples with different liquid repellency states. Glass substrate is hydrophilic and oleophilic. Fused titania oxide coating makes it hydrophilic and superoleophilic. Hydrogel coating was hydrophilic and superoleophilic. After casting of hydrogel mixed with silica 7 nm hydrophilic nanoparticles, samples are superhydrophobic and oleophilic. After UVO treatment, they became superliquiphilic, and after fluorosilane vapour deposition samples became superliquiphobic with a low tilt angle. It should be noted that treated samples may show some hydrophobic recovery with time, therefore, the fluorosilane deposition was carried out soon after the UVO treatment.

Figure 5.

Droplets deposited on various samples with different liquid repellency states. The superhydrophobicity was achieved through hydrogel-nanoparticle coating. Superliquiphobicity was achieved through hydrogel-nanoparticle coating followed by fluorosilane vapour deposition.

(c). Self-cleaning

Figure 6 shows optical images of the glass substrate and superliquiphobic surfaces with low tilt angles contaminated by silicon carbide particles and after washing with water droplets. The bar chart shows measured per cent of particles removed by water droplets. The sliding behaviour of the water droplet on the as-received surface clumps together the debris and does not remove it. The rolling behaviour of droplets on superliquiphobic surfaces effectively removes debris from the coatings.

Figure 6.

Optical images of the glass substrate and superliquiphobic surfaces covered by silicon carbide particles and then washed by water. Coated surfaces became clean by rolling water droplets. The rolling behaviour of the water droplet removes debris from the superliquiphobic surfaces. The glass surface remained dirty because of spreading water droplets on the hydrophilic surface. (Online version in colour.)

(d). Icephobicity

The anti-icing behaviour was tested using supercooled water droplets released onto superliquiphobic surfaces inclined at 10°. Figure 7a shows the supercooled droplets (−18°C) placed on surfaces at −60°C. Frost was formed on both glass and superliquiphobic glass samples at −60°C, as can be observed from the images in figure 7a. The supercooled water droplet froze on the as-received hydrophilic surface immediately after deposition on the sample at −60°C. Water droplets rolled off the superliquiphobic surfaces before freezing on the aluminium block.

Figure 7.

(a) Supercooled DI water droplet (at −18°C) placed on a glass substrate and superliquiphobic hydrogel + NP + fluorosilane. The droplet slid off the superliquiphobic surface, whereas it got stuck on the glass surface. The surface exhibited icephobicity at low temperatures down to −60°C. (b) Video stills of droplets on the glass surface show that the droplets were stuck to the surface and they bounced off the superliquiphobic surface. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 7b shows video stills of supercooled water droplets falling from a height of 1 cm on surfaces at −60°C. On the glass sample, droplets got stuck immediately. On the superliquiphobic glass surface, water droplets bounced and rolled off the surface. The supercooled water droplets rolled off the superliquiphobic surface due to the high water contact angles exhibited by this surface. Additionally, as it rolled across the surface, the water droplet removed ice crystals due to the reduced ice adhesion strength caused by a reduced ice-solid contact area. This is in agreement with previous studies which show that ice adhesion strength on rough surfaces has a good correlation with contact angle hysteresis or tilt angle, and therefore the ice-solid contact area [32]. As stated earlier, ice crystals have lower adhesion strength to the superliquiphobic surface and can be shed by taking advantage of external forces, such as gravity or aerodynamic forces, to overcome the ice-surface adhesion forces. For completeness, the size of the droplets was 0.5–2 mm with an approach velocity of 0.1–0.2 m s−1. After hitting the surface, droplets moved over an inclined superliquiphobic surface at a similar speed.

(e). High-temperature durability

The ability to sustain superliquiphobic properties at a high temperature of 95°C was examined. Figure 8 shows the contact angles of water and hexadecane droplets at ambient, 50°C, and 95°C. No significant change in apparent contact angles with a water droplet was measured. The contact angle with hexadecane droplets started to decrease slightly above 50°C to 147° ± 2° at 95°C. Tilt angles could not be measured as experiments were performed on a hot plate. Based on watching the droplet movement while tilting the hot sample, the tilt angle did not appear to change with water droplets. However, the tilt angle increased for hexadecane droplets above 85°C to about 15° at 95°C. The data suggest that the liquid repellency is maintained up to about 95°C.

Figure 8.

Water and hexadecane (red pigmented) droplets placed on the heated superliquiphobic surfaces. The graph shows apparent contact angles at elevated temperatures. The coating retained superliquiphobic properties up to 95°C. (Online version in colour.)

(f). Wear test

In order to assess improvement in wear performance of the hydrogel coatings, the wear tests were also performed on methylphenyl silicone resin with and without nanoparticles.

Figure 9a shows optical micrographs of methylphenyl silicone resin and hydrogel on the glass, also on superliquiphobic methylphenyl silicone + NP + fluorosilane and hydrogel + NP + fluorosilane surfaces before and after wear experiment. A burnished track designated by a dashed line was observed on methylphenyl silicone and methylphenyl silicone + NP + fluorosilane coated surfaces after wear experiment at a load of 10 mN. There was visible wear damage at a higher load of 50 mN. In the case of hydrogel with and without nanoparticles, a very slight sign of burnishing was shown by the hydrogel surface. In order to determine any degradation in the wettability of the wear track, water droplets were dragged over the wear track, rolled over the track and placed on wear and rolled over, as shown in figure 9b. Droplets could be dragged over the wear track and also rolled over the wear track. To allow droplets placed on the wear tracks to roll, the tilt angle increased, which is expected. The wear data suggest that the superliquiphobic hydrogel surface remained liquiphobic after wear experiment.

Figure 9.

(a) Optical images of before and after wear experiment using ball-on-flat tribometer using a 3 mm diameter sapphire ball with 50 mN load on the hydrogel + NP + fluorosilane coatings. For comparison, experiments were run on methylphenyl silicone and methylphenyl silicone + NP + fluorosilane coatings, commonly used in liquid repellent surfaces. (b) Images of water droplets before and after wear. Droplets were dragged over the wear track in the direction of arrows. Before the wear test, droplets dragged without resistance. After the wear test, droplets dragged with resistance at the track. Before the wear test, droplets rolled off the surface at 5° ± 1° tilt angle and for the worn samples, rolled over the wear track at 8° ± 1° tilt angle. Droplets placed directly on the wear track rolled over the wear track at 47° ± 5° tilt angle. (Online version in colour.)

(g). Scratch test

To understand their self-healing capabilities, hydrogel coatings were scratched with a knife and hydrated. The images of coatings before and after scratching were compared to assess for any self-healing. Scratch tests were performed on coated samples without nanoparticles to be able to identify clearly the damage and any subsequent self-healing as a result of hydration. For comparison, methylphenyl silicone resin coating was also scratched. Figure 10 shows optical images of methylphenyl silicone resin and hydrogel coatings on glass immediately after the scratch test. There was a visible cut designated by a dashed line on the methylphenyl silicone and hydrogel-coated surfaces after the scratch experiment. To demonstrate self-healing capability, water droplets were placed on the cuts and images were taken after the droplets evaporated. After water treatment, the cut remained on methylphenyl silicone resin coating; however on the hydrogel coating, there was no visible cut. In another test, the scratched sample was cooled down to about 5°C to promote water condensation. After about 15 min, the scratch was repaired.

Figure 10.

Optical images after the scratch experiment using a knife on the methylphenyl silicone resin and hydrogel coatings. After the scratch test, water droplets were placed directly on the scratch track and after evaporation of water, new images were taken. Hydrogel coating repaired after hydration. (Online version in colour.)

4. Conclusion

To fabricate a self-healing, liquid repellent, icephobic and self-cleaning surface, a coating of cross-linked PAAm hydrogel was chosen as a binder for the nanoparticle-hydrogel coating due to its ease of fabrication. The hydrogel coating can self-heal with an external stimulus of humidity. Acrylamide hydrogel solution was mixed with hydrophilic silica nanoparticles, cast and dried to obtain superhydrophobic properties. A top layer of fluorosilane exhibited superhydrophobicity with low tilt angle and superoleophobicity. The anti-icing properties of the coating were examined at temperatures down to −60°C. The supercooled water droplets rolled over the frozen superliquiphobic samples and bounced off the surfaces. Superliquiphobic properties of the coating were maintained on heated surfaces up to 95°C. The coating exhibited self-cleaning properties with high mechanical durability. Hydrogel coating also demonstrated self-healing capability after hydration.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dev Gurera for critical reading of the manuscript.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The financial support for this research was provided in part by the Ford Research and Innovation Center, Dearborn, MI and a seed grant GOGCAP from the Center for Applied Sciences (CAPS) at The Ohio State University.

References

- 1.Zwaag S. 2007. Self healing materials: an alternative approach to 20 centuries of materials science. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cremaldi J, Bhushan B. 2018. Fabrication of bioinspired, self-cleaning superliquiphilic/phobic stainless steel using different pathways. J. Colloid Interface. Sci. 518, 284–297. ( 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.02.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhushan B. 2018. Biomimetics: bioinspired hierarchical-structured surfaces for green science and technology, 3rd edn Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilar MR, San Román J. 2019. Smart polymers and their applications, 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Tao X, Zhao T, Weng L, Kang E, Wang L. 2015. Antifouling and antibacterial hydrogel coatings with self-healing properties based on a dynamic disulfide exchange reaction. Polym. Chem. 6, 7027–7035. ( 10.1039/C5PY00936G) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor DL, et al. 2016. Self-healing hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 28, 9060–9093. ( 10.1002/adma.201601613) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonkers H. 2007. Self-healing concrete: a biological approach. In Self-healing materials: an alternative approach to 20 centuries of materials science (ed. van der Zwaag S.), pp. 195–204. Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li VC, Yang EH. 2007. Self healing in concrete materials. In Self healing materials: an alternative approach to 20 centuries of materials science (ed. van der Zwaag S.), pp. 161–193. Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diesendruck C, Sottos N, Moore J, White S. 2015. Biomimetic self-healing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10 428–10 447. ( 10.1002/anie.201500484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treossi E, Liscio A, Feng X, Palermo V, Mullen K, Samori P. 2009. Temperature-enhanced solvent vapor annealing of a C3 symmetric hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene: controlling the self-assembly from nano- to macroscale. Small 1, 112–119. ( 10.1002/smll.200801002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossegger D, Gomez-Meijide B, Vansteenkiste S, Garcia A. 2018. Influence of rheological and physical bitumen properties on heat-induced self-healing of asphalt mastic beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 182, 298–308. ( 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.148) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amamoto Y, Otsuka H, Takahara A, Matyjaszewski K. 2012. Changes in network structure of chemical gels controlled by solvent quality through photoinduced radical reshuffling reactions of trithiocarbonate units. ACS Macro Lett. 1, 478–481. ( 10.1021/mz300070t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogsgaard M, Hansen M, Birkedal H. 2014. Metals & polymers in the mix: fine-tuning the mechanical properties & color of self-healing mussel-inspired hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. B 2, 8292 ( 10.1039/C4TB01503G) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phadke A, Zhang C, Arman B, Hsu CC, Mashelkar RA, Lele AK, Tauber MJ, Arya G, Varghese S. 2012. Rapid self-healing hydrogels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4383–4388. ( 10.1073/pnas.1201122109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asoh T, Kawai W, Kikuchi A. 2014. Alternating-current electrophoretic adhesion of biodegradable hydrogel utilizing intermediate polymers. Colloids Surf. B 123, 742–746. ( 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.10.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim C, Kim D. 2017. Durability and self-healing effects of hydrogel coatings with respect to contact condition. Sci. Rep. 7, 6896 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-07106-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbucci R. 2009. Hydrogels. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar AC, Erothu H. 2017. Synthetic Polymer Hydrogels. In Biomedical applications of polymeric materials and composites (eds Francis R, Kumar S), pp. 141–162. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Iyer G, Nadarajah FJM, Spongberg AL. 2010. Polyacrylamide hydrogel properties for horticultural applications. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charac. 15, 307–318. ( 10.1080/1023666X.2010.493271) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoine E, Vlachos P, Rylander M. 2014. Review of collagen in hydrogels for bioengineered tissue microenvironments: characterization and mechanics, structure, transport. Tissue Eng. B. Rev. 20, 683–696. ( 10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0086) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed E. 2015. Hydrogel: preparation, characterization, and applications: a review . J. Adv. Res. 6, 105–121. ( 10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis R, Erothu H. 2017. Biomedical applications of polymeric materials and composites. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimes CA, Mor GK. 2009. Tio2 nanotube arrays: synthesis, properties, applications. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D, Wang X, Liu X, Zhou F. 2010. Engineering a titanium surface with controllable oleophobicity and switchable oil adhesion. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 9938–9944. ( 10.1021/jp1023185) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostapchenko V, Huang Q, Zhang Q, Zhao C. 2017. Effect of TiCl4 treatment on different TiO2 blocking layer deposition methods. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 12, 2262–2271. ( 10.20964/2017.03.61) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhushan B. 2013. Introduction to tribology, 2nd edn New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhushan B. 2017. Nanotribology and nanomechanics: an introduction, 4th edn Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning R, Ewing J. 2009. Temperature in cars survey. Brisbane, Australia: RACQ Vehicle Technologies Department. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhushan B, Martin S. 2018. Substrate-independent superliquiphobic coatings for water, oil, surfactant repellency: an overview. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 526, 90–105. ( 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.04.103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung W, Axelson D, van Dyke J. 1987. Thermal degradation of polyacrylamide and poly(acrylamide-co-acrylate). J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 25, 1825–1846. ( 10.1002/pola.1987.080250711) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown PS, Bhushan B. 2015. Bioinspired, roughness-induced, water and oil super-philic and super-phobic coatings prepared by adaptable layer-by-layer technique. Sci. Rep. Nat. 5, 14030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulinich SA, Farzaneh M. 2009. How wetting hysteresis influences ice adhesion strength on superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir 25, 8854–8856. ( 10.1021/la901439c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.