Abstract

Pheochromocytoma is a sympathetic paraganglioma originating from the chromaffin cells. They are bilateral in 10% of cases and occur as a part of a MEN 2A or 2B syndromes. This is a case of bilateral asymptomatic pheochromocytomas diagnosed incidentally on imaging in a woman being investigated for secondary infertility. Laboratory tests were negative. Whole body FDG scan showed avid uptake of the tracer by both adrenal masses, but none in the thyroid. Hypertensive crisis occurred during right adrenalectomy on an unprepared patient in spite of clamping the adrenal vein, which raises the need for alpha-adrenergic blockade for patients undergoing adrenalectomy.

1. Introduction

Incidental finding of unilateral adrenal masses on cross-sectional imaging is relatively common. However, bilateral adrenal masses are uncommon and present with variable clinical presentations from asymptomatic to severe systemic symptoms, and have variable etiologies such as bilateral adrenocortical neoplasms, lymphomas, pheochromocytomas, metastasis, and others.1

In this article, we report a case of incidental asymptomatic bilateral large adrenal pheochromocytomas in a young woman presenting for investigation of infertility.

2. Case presentation

We report the case of a 28-year-old woman, healthy, who presented to the clinic for workup of secondary infertility. Patient reports headaches, dizziness and irregular menses. However, she denies palpitations, hot flushes, or weight changes. No family history of endocrine disorders, or seizures. Her blood pressure reading in the clinic was 130/85 with a regular heart rate of 87/minute. Her physical exam was unremarkable, with no thyroid enlargement, no tremors, no skin hyperpigmentation or orthostatic hypotension, no mucosal neuromas.

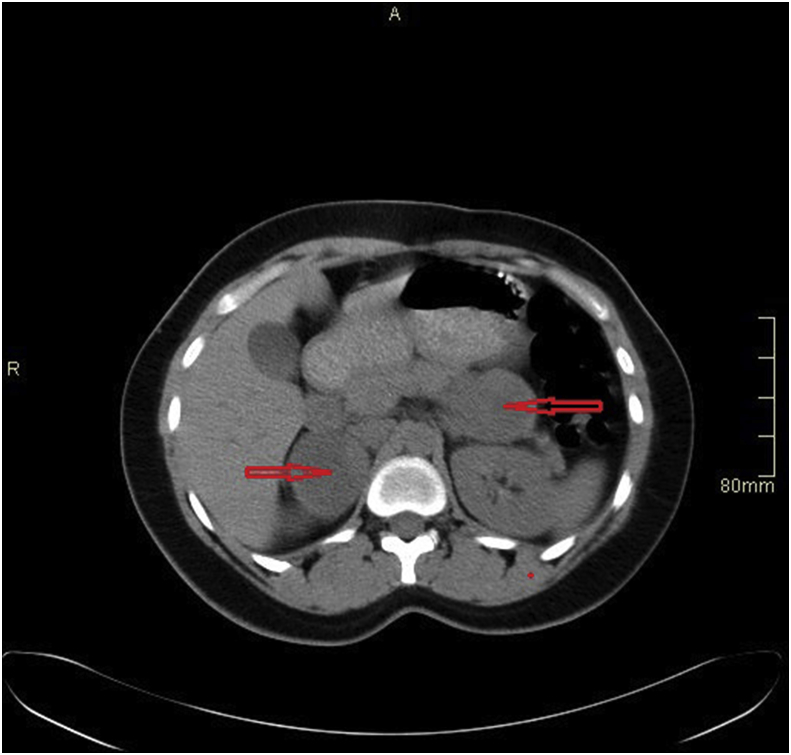

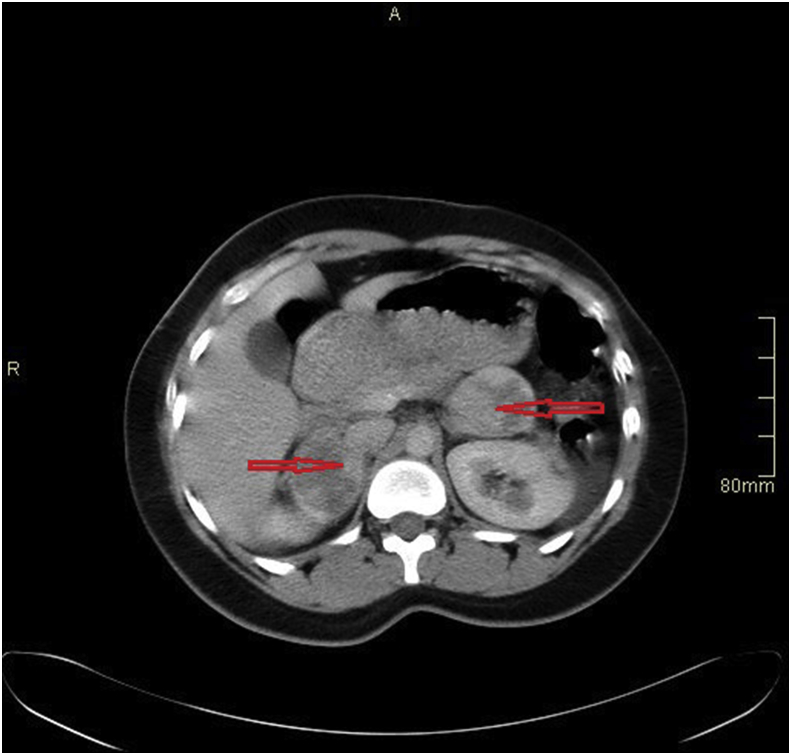

CT abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) done as part of the workup for secondary infertility showed bilateral adrenal masses (Right: 58 × 45 × 45mm, left: 44 × 38 × 36mm), both showing internal necrosis and heterogeneous enhancement post contrast administration, with no invasion of adjacent structures.

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen pre IV contrast showing bilateral adrenal masses.

Fig. 2.

CT abdomen post IV contrast showing bilateral adrenal masses with internal necrosis and heterogeneous enhancement.

Her metabolic workup included: serum creatinine, electrolytes, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, aldosterone, renin, serum metanephrine and normetanephrine, calcitonin, prolactin, 24-h urine collection for catecholamines. All her lab results were within normal ranges. Overnight 1mg Dexamethasone suppression test was also normal.

Whole body PET-FDG showed two FDG-avid enlarged and necrotic bilateral adrenal masses measuring respectively 5.2cm with SUVmax 11.2, and 4.7cm with SUVmax 8.6, with no uptake in the thyroid.

After a multidisciplinary meeting, the decision was to perform a diagnostic biopsy. Transgastric EUS-guided core biopsies of the mass in the left adrenal were taken. The procedure was uneventful and biopsy results were consistent with neuroendocrine cells that may be derived from normal adrenal medulla or may represent a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor. Ki-67 proliferation marker was low (<2%).

Patient underwent robotic assisted left partial adrenalectomy one week after the biopsy. The operation was uneventful with no hypertensive spikes while manipulating the left adrenal gland. Final pathology reported a 4cm pheochromocytoma with no histologic evidence of malignancy. The diagnosis of non-secreting pheochromocytoma was considered and decision was made to perform a right adrenalectomy without preoperative alpha or Beta blockage.

One month after the first surgery, the patient underwent a right robotic assisted adrenalectomy. A “No-touch” technique was used until clamping of the adrenal vein was secured. Despite all measures a hypertensive crisis occurred with systolic blood pressure reaching up to 290 mmHg once the adrenal gland was manipulated. This required stopping further manipulation of the gland and controlling blood pressure with IV nicardipine, nitroglycerine, and remifentanil. The anesthesia team was ready despite the previous reassuring surgery where no hypertensive crisis was noted. All medication were preemptively prepared and hooked to the IV line.

After controlling the blood pressure, careful dissection of the IVC and renal vein revealed a secondary adrenal vein that was clipped resulting in a severe hypotension that required norepinephrine drip; it was subsequently weaned gradually over 2 h. Pathology revealed a 4.5cm pheochromocytoma with no capsular invasion, atypia, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion or increased mitotic figures.

Postoperative recovery was uneventful and patient was vitally stable, on no steroid replacement. A follow up ACTH, cortisol and electrolytes was normal.

3. Discussion

Bilateral adrenal masses are rare and have several etiologies like hyperplasia, adrenocortical neoplasm, metastases, pheochromocytomas, tuberculosis, and lymphomas.

Patients with pheochromocytoma usually present with hyperadrenergic signs and symptoms due to sympathetic overstimulation.1 The reported incidence of pheochromocytomas is about 2–8 case per million.2

The literature on bilateral pheochromocytomas is scanty and limited to case reports and few case series on bilateral adrenal masses. Pheochromocytomas are bilateral in 10% of cases and occur more often as part of a MEN2A or 2B syndrome.2

In our case, we report an asymptomatic bilateral pheochromocytoma in a young woman incidentally found during investigation of secondary infertility. Our patient was examined for clinical signs that suggest a familial disease such as neurofibromatosis, but were clinically excluded by their absence.

Normal serum calcium, parathyroid hormone and calcitonin ruled out MEN 2A or 2B syndrome.

In addition, the absence of similar familial cases helped exclude a familial etiology.

Combination of various tests including 24-h urine collection for catecholamines, plasma free metanephrines and EUS-guided fine needle biopsy did not improve the diagnostic yield of pheochromocytoma preoperatively. However, the PET scan using the tracer (18-fluoro-dihydroxyphenylalanine) showed avid uptake of the adrenal masses, which goes with the high sensitivity of this imaging modality in localizing pheochromocytoma; the sensitivity was reported to reach 100%.3

In our case, the patient presented with a biochemically silent pheochromocytoma. She did not develop a hypertensive crisis during the EUS-guided fine needle biopsy and during the left adrenalectomy, though no specific medical preparation was given to the patient pre-procedure. After pathological confirmation of pheochromocytoma, the need for pre-operative preparation for the second procedure was discussed and it was decided not to give alpha-blockers. However, during the right adrenalectomy a hypertensive crisis developed despite clipping the adrenal vein, which highlights two important issues: the necessity of preparing the patient before the second operation even in the case of silent pheochromocytoma4,5 and the necessity to take precautions while dissecting the adrenal gland even after clipping the adrenal vein, since other tributaries may still be present.

4. Conclusion

The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma should still be considered in young asymptomatic patients with atypical clinical presentation who have bilateral adrenal masses, negative family history and negative adrenal metabolic workup. Preoperative alpha-adrenergic blockade should be considered in all patients once the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma is confirmed, even if the patient is asymptomatic or if the manipulation of the other adrenal did not result in a hypertensive crisis. A high preparedness level should be exerted by having antihypertensive medications ready and connected to the IV line, since any delay in the treatment of severe hypertensive crisis may result in serious adverse cardiovascular events.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient. She was informed that the case will be written for publication as case report with the accompanying images.

The consent is available upon request.

Author contributions

Robert Zakhia El-Doueihi: Contribution by study design and idea.

Ibrahim Salti: Contributed by writing the discussion and checking overall paper.

Marie Maroun-Aouad: Contributed by writing the discussion and conclusion and checking overall paper.

Albert El Hajj: Contributed by writing the introduction and providing data and checking overall paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100876.

Contributor Information

Robert Zakhia El-Doueihi, Email: rz32@aub.edu.lb.

Ibrahim Salti, Email: isalti@aub.edu.lb.

Marie Maroun-Aouad, Email: mm01@aub.edu.lb.

Albert El Hajj, Email: ae67@aub.edu.lb.

Funding

No funding provided.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kloos R.T., Gross M.D., Francis I.R., Korobkin M., Shapiro B.S. Incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:460–484. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-4-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plouin P.F., Gimenez-Roqueplo A.P. Pheochromocytomas and secreting paragangliomas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lomte N., Bangdar T., Khare S. Bilateral adrenal masses: a single-center experience. Endocr Connect. 2016;5:92–100. doi: 10.1530/EC-16-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069–4079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacs M., Lee P. Preoperative alpha-blockade in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma: is it always necessary? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2017 Mar;86(3):309–314. doi: 10.1111/cen.13284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.